Abstract

Recombinant interferon-β (IFN-β) remains the most widely prescribed treatment for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). Despite widespread use of IFN-β, the therapeutic mechanism is still partially understood. Particularly, the clinical relevance of increased B cell activity during IFN-β treatment is unclear. In this manuscript, we show that IFN-β pushes some B cells into a transitional, regulatory population which is a critical mechanism for therapy. IFN-β treatment increases the absolute number of regulatory CD19+CD24++CD38++ transitional B cells in peripheral blood relative to treatment naive and Copaxone treated patients. In addition we found that transitional B cells from both healthy controls and IFN-β treated MS patients are potent producers of IL-10, and that the capability of IFN-β to induce IL-10 is amplified when B cells are stimulated. Similar changes are seen in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). IFN-β treatment increases transitional and regulatory B-cell populations as well IL-10 secretion in the spleen. Furthermore, we found that IFN-β increases autoantibody production, implicating humoral immune activation in B cell regulatory responses. Finally, we demonstrate that IFN-β therapy requires immune regulatory B cells by showing that B cell deficient mice do not benefit clinically or histopathologically from IFN-β treatment. These results have significant implications for the diagnosis and treatment of relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis.

Introduction

Type I IFNs, which include IFN-β, elevate expression of B cell activation factor (BAFF), increase B cell activity and drive the production of autoantibody in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and neuromyelitis optica (NMO), promoting inflammation(1–3). In one sense, these are “type 1 IFN diseases” where B cell autoantibody production is clearly pathogenic. In RRMS IFN-β also increases serum levels of BAFF and B cell activity(4, 5), yet in a seeming paradox IFN-β reduces inflammation and decreases relapses(6). For twenty years IFN-β has been the leading therapy for RRMS. Other studies have shown that IFN-β alters the function of T-cells and myeloid cells in RRMS and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) to reduce disease severity(7, 8). The experiments described in this manuscript report a novel, previously unappreciated therapeutic mechanism for IFN-β in which therapy maintains a population of BAFF-dependent regulatory B cells that suppresses cell-mediated CNS inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Patient recruitment, PBMC isolation and flow cytometry

RRMS patients and healthy volunteers were recruited and consented at Stanford Blood Center and Stanford Multiple Sclerosis Center or the Oklahoma Multiple Sclerosis Center of Excellence under IRB approved protocols. Patient disease diagnosis and activity were assessed by credentialed neurologists. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy donors and RRMS subjects were isolated by centrifugation through Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Life Sciences). PBMCs were frozen in 5% BSA and 10% DMSO prior to being thawed in a 37 degree water bath. Cells were then washed with 1% FCS in PBS and stained with 10% human serum to block Fc receptors prior to incubation with the following anti-human antibodies: FITC anti-CD24 (BioLegend), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD19 (BioLegend), PE anti-CD38 (BioLegend), PacBlue anti-IgM (Biolegend), PE-Cy7 anti-IgD (BioLegend), or APC anti-CD268 (BioLegend), or PacificBlue anti-CD27 (BioLegend). PBMCs were analyzed using either the BD FACSscan or LSRII. Absolute numbers of B-cell subsets per ul of blood was calculated by multiplying the particular cell population frequency by the number of live cells/ul of blood recovered after PBMC isolation. Human BAFF levels were measured in plasma by using the human BAFF ELISA kit (R&D). The healthy controls were all male yet the primary focus is on the comparison between treatment naïve, IFN-β and GA patients, and there has not been evidence suggesting gender plays a pivotal role in the response of RRMS to IFN-β.

Mice

C57BL/6 and muMT mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and subsequently bred at the Stanford or the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation shared animal facilities. All animals were housed and treated in accordance with guidelines and approved by the IACUC at each institution.

In Vitro stimulation of PBMCs

For intracellular FACS of IL-10 in B-cell populations, we obtained fresh PBMCs from 5 IFN-β treated MS patients and 5 healthy volunteers and cultured at 2.5×106 cells/ml with 3ug of anti-human Ig (Jackson Immunoresearch), 1ug of anti-human CD40 (Ebioscience), 40nM CpG ODN 2006 (Invivogen), and Brefeldin A (GolgiPlug, BD Bioscience) in complete RPMI supplemented for 5 hrs then surface stained with anti-CD19 PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD24 FITC and anti-CD38 PE. Cells were then fixed, permeablized using the intracellular FACS kit (BD Bioscience) and stain with anti-human IL-10 APC (Biolegend). To assess secreted IL-10 by ELISA, fresh PBMCs (2.5×106 cells/ml) from 3 healthy volunteers were stimulated with or without anti-human Ig, anti-human CD40 and CpG in the presence or absence of 1000 units/ml of recombinant human IFN-β (PBL interferon source) for 72 hrs. IL-10 in culture supernatants were assessed by a Human IL-10 ELISA Kit (eBioscience).

EAE induction

Eight to ten weeks old, female C57BL6/J and muMT mice were induced with EAE by an immunization with 150μg of MOG p35–55 (Stanford) emulsified in CFA (4mg/ml of heat-killed m. tuberculosis) followed by an intraperitoneal injection of 500 ng Bordetella pertussis toxin (Difco laboratories) in PBS at the time of and two days following immunization. Paralysis were monitored daily using a standard clinical score ranging: 1) Loss of tail tone, 2) incomplete hind limb paralysis, 3) complete hind limb paralysis, 4) forelimb paralysis, 5) moribund/dead. Mice were treated every second day with 10,000 units per dose of recombinant mouse IFN-β (PBL) or vehicle (0.5% albumin in PBS) from EAE day 6 to day 20.

In Vitro stimulations of mouse spleen cells

Single cell suspensions of spleen cells from mice with EAE were cultured at 2.5×106 cells per ml in complete RPMI with 1ug/ml of MOG35–55 peptide for 72 hours. IL-10 from the culture supernatants were assessed by an IL-10 ELISA Kit (Ebioscience).

Passive Transfer of B cells

EAE mice treated with IFN-β or vehicle were sacrificed at EAE day 10 and B cells were isolated from spleen cells by magnetic sorting using anti-B220 conjugated magnetic beads (Miltenyi). 20×106 B cells from either IFN-β or vehicle treated donor mice were injected (I.P.) into recipient C57BL/6 mice at EAE day 6 and disease was monitored for 25 days. Histology. Brains and spinal cords were dissected from EAE mice and the tissue was fixed in 10% formalin in PBS and embedded in a single paraffin block. Sections 8 μm thick were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and luxol fast blue and imaged using a Nikon Eclipse E200 light microscope and a Nikon DS-V2 camera.

Flow cytometry analysis of EAE tissue

Infiltrating cells were isolated from spinal cords from 3–4 perfused animals. CNS homogenates were incubated with collagenase and DNAse for 1h at 37°C and cells were purified by a Percoll gradient. Single-cell suspensions of spleen, DLN, bone marrow and infiltrating CNS cells were incubated with unconjugated anti-CD16/CD32 then stained with aqua-amine live/dead stain and combinations of the following antibodies CD21-FITC, CD23-Biotin (Streptavidin-Qdot605), CD267-Alexa647, IgD-Alexa700, B220-APC-Cy7, CD138-PE, IgM-PECy7, CD19-PECy5.5, CD43-Alexa647, CD1d-PE. Cells were then analyzed on an LSRII. Serum BAFF and anti-MOG antibody detection. Mouse BAFF was measured in plasma by using the mouse BAFF ELISA kit (R&D). Levels of anti-MOG antibodies in mouse plasma were performed using sandwich ELISAs. In brief, EIA plates were coated with 10 ug/ml of MOG p35–55 peptide. Plates were probed with 1/100 dilutions of serum from individual mice and reactive Abs were detected using peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse specific for IgG or IgM (Southern Biotech) and developed with TMB.

Results

IFN-β therapy increases specific B cell populations in RRMS patients

Since IFN-β treatment increases serum BAFF concentration, a known survival factor for transitional B cells and plasma blasts/cells in humans(9), we hypothesized that these B cell subsets would be increased in the peripheral blood of RRMS patients taking IFN-β. Under an IRB-approved protocol, we recruited patients who were either treatment naïve or actively using a prescribed preparation of recombinant IFN-β or Copaxone (glatiramer acetate or GA) for peripheral blood draw. The RRMS patients gave their written informed consent for this study, and were similar in age and sex (supplemental Table).

In our patient cohort there was a trend that serum BAFF levels, measured by ELISA, were elevated in patients on IFN-β compared to patients on GA but this was not statistically significant (IFN-β: 819.3pg/ml±92.8; GA: 691.9pg/ml±23.8, data not displayed). However, we did observe that IFN-β treated RRMS patients had a statistically significant increase in the frequency of CD19+ B cells relative to treatment naïve and GA treated MS patients and to healthy controls (Fig. 1A and B). There was also significant increase in the absolute numbers of B cells in the IFN-β treated MS patients compared to the treatment naïve patients (Fig 1C). We then assessed the transitional B cell population defined by surface CD19+CD24++CD38++ (Fig. 1D–F), a population of B cells shown to have immune regulatory function in humans(10). We found that both the frequency and absolute numbers of transitional B cells were increased in the IFN-β treated patients compared to the treatment naïve and GA MS patients (Fig. 1D–F). We further subdivided transitional B cells into the transitional 1 and 2 subsets, T1 and T2, by expression of IgM, IgD (Fig. 1G). We found the absolute number of T1 and T2 B cells were significantly increased in IFN-β treated patients compared to treatment naïve MS patients (supplemental Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1. IFN-β therapy increases transitional B cells in blood from RRMS patients.

PBMCs from treatment naïve, IFN-β treated and GA treated as well as healthy controls were analyzed using flow cytometry for the following: the frequency (A and B) and absolute # (C) of total CD19+ B cells; the frequency (D and E) and absolute # (F) of CD19+CD24++CD38++ transitional B cells; the frequency (G) of transitional-1 and -2 (T1 and T2) B cells; the frequency (H and I) and absolute # (J) of CD19+CD38-IgM-IgD- class-switched memory B cells; and the frequency (K and L) and absolute # (M) of CD19+CD27++CD38++ plasmablasts. Statistical significance was determined by one-way anova (***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05).

We also assessed other B cell subsets in our cohort of RRMS patients. The frequency but not absolute number of class-switched memory B cells, represented by CD19+CD38-IgM-IgD- (Fig 1H), was significantly decreased in IFN-β treated patients compared with treatment naïve and GA patients (Fig 1H–J). Finally, we observed a statistically significant increase in the absolute number but not frequency of plasmablasts, defined as CD19+CD27++CD38++ (Fig 1K)(11), in patients taking IFN-β compared to treatment naïve MS patients (Fig. 1K–M). In summary, the data show that transitional B cells and plasmablasts are increased in the peripheral blood during IFN-β treatment compared to treatment naïve patients, while class-switched memory cells are not. GA treated patients did not demonstrate these changes. Therefore, the observed changes in B cells in IFN-β treated patients was directly due to IFN-β treatment and not a general feature of MS disease in remission.

Transitional B-cells are a major source of IL-10 in MS patients treated with IFN-β

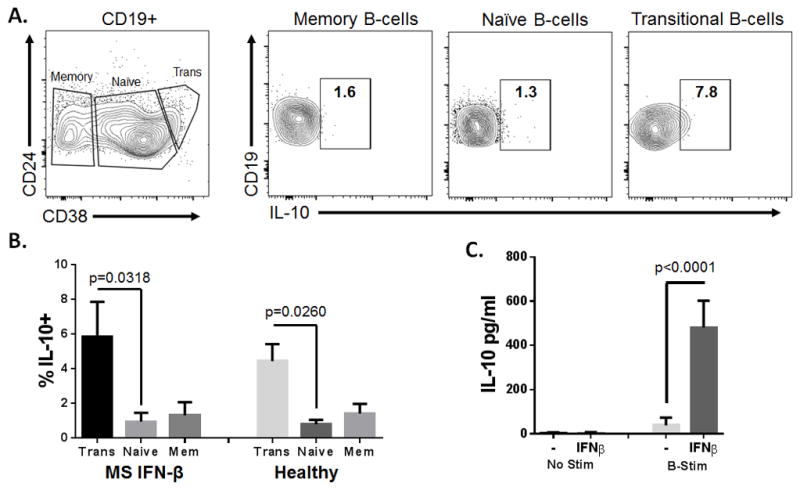

It has recently been shown that the transitional B cell population has a regulatory function in healthy individuals and is capable of producing large amounts of IL-10 to suppress antigen mediated T-cell activity in healthy individuals(10). Yet in lupus, transitional B cells lack IL-10 dependent regulatory function and instead drive both effector T-cell function and antinuclear autoantibody production(10). We found that IFN-β treatment pushes the expansion of transitional B-cells, however the functionality of transitional B-cells in MS is currently unknown. To address this, we assessed the relative amount of IL-10 expressed in transitional B-cells (CD19+CD24++CD38++) compared to naïve (CD19+CD24+CD38+), and memory B-cells (CD19+CD38-) from 5 IFN-β-treated MS patients and 5 healthy volunteers by intracellular FACS (see materials and methods) (Fig. 2 A). We found that the transitional B-cells expressed significantly more IL-10 compared to naïve B-cells in both IFN-β-treated MS patients and healthy volunteers (Fig 2. A and B). In addition, we found that the transitional B-cells expressed more IL-10 compared to memory B-cells though these results did not reach statistical significance. These data demonstrate that the IL-10 dependent regulatory function of transitional B-cells is intact in IFN-β treated MS patients.

Figure 2.

IL-10 expression in B-cell subsets. (A) Representative analysis of intracellular IL-10 staining in transitional (CD19+CD24++CD38++), naïve (CD19+CD24+CD38+), and memory (CD19+ CD38-) B cells. (B) Frequency of IL-10+ cells in transitional, naïve and memory B cells from 5 IFN-β-treated MS patients and 5 healthy volunteers. Statistical significance was determined by one-way anova. (C) IFN-β (1000U/ml) increases IL-10 secretion in PBMCs from healthy volunteers stimulated with anti-Ig, anti-CD40 and CpG (B-stim). IL-10 was measured in culture supernatants by ELISA and statistical significance was determined by a Student’s T-test. The error bars represent S.E.M.

We next determined the effects IFN-β has on PBMCs from healthy volunteers cultured in the presence or absence of B-cell stimulatory conditions. We found that PBMC’s stimulated with IFN-β alone had no effect on the secretion of IL-10. Strikingly, when PBMC were stimulated with anti-IgM, anti-CD40L and CpG, conditions that stimulate B-cell activity (B-stim), IFN-β significantly increased the secretion of IL-10 (Fig. 2C). Since these experiments were performed on whole PBMC cultures, it remains to be determined whether IFN-β acts directly or indirectly on B-cells to increase IL-10 secretion. We are actively pursuing this avenue of research. Nonetheless, these data clearly demonstrate that the combination of IFN-β and B cell stimulation induces a potent IL-10 response.

IFN-β treatment of EAE alters B cell subsets towards a regulatory transitional phenotype

Since IFN-β increased transitional B cells and plasmablasts in RRMS, we next assessed the effect IFN-β treatment had on B cells in EAE. We treated mice with recombinant mouse IFN-β (10,000 units/dose) or vehicle every second day beginning at EAE day 6 and sacrificed mice for analysis on EAE day 13–16. We found that IFN-β treatment increased levels of BAFF in serum, measured by ELISA, and increased the absolute number of CD19+ B cells in the spleens of WT EAE mice (Fig. 3A and B). This increase in B cell numbers was associated with successful treatment (Fig. 5A). We next assessed the specific B cell subsets affected by treatment by flow cytometry. Specifically, we measured the number of transitional (T1 and T2), marginal zone, follicular, plasma cells and CD1d+CD5+ regulatory B cells in the spleen by flow cytometry (supplemental Fig. 2). We observed that EAE mice treated with IFN-β had significantly higher absolute numbers of splenic T2 B cells, IgD+ and IgD− marginal zone B cells, and follicular B cells compared to mice treated with vehicle (Fig 3. C, D and E). There was a trend of elevated T1 B cells and splenic plasma cells in the mice treated with IFN-β compared to vehicle treated (Fig. 3 C and G). In addition, we found that the regulatory B cell subset of CD19+CD23loCD5+CD1dhiIgMhi B cells were significantly increased in the spleens from IFN-β treated mice compared to vehicle treated (Fig. 3F). Splenic CD19+CD23loCD5+CD1DhiIgMhi B cells share many features with the B1a B cell subset and have been recently described as a regulatory B cell subset(12–14). We also found an elevated percentage of newly formed transitional B cells (AA4.1+CD19+) in the peripheral blood of WT EAE treated with IFN-β compared to WT EAE treated with vehicle (Fig. 3H). This increase in B-cell numbers after therapy was also associated with reduced disease. We found an inverse correlation between both EAE severity and the frequency of CD19+ B cells in the spleens, draining lymph nodes, and bone marrows of mice (Fig. 3I and Supplemental Fig. 3). B cells may regulate inflammation in secondary lymphoid tissue or locally within the inflamed CNS tissue. We found no significant differences in the number of B cells in the spinal cords of IFN-β or vehicle treated EAE mice (Fig. 5D) which suggests that B cells regulate the immune response in the secondary lymphoid tissue and not the CNS.

Figure 3. IFN-β treatment alters B cell populations in mice with EAE. Mice with EAE were treated with IFN-β (10,000U/dose) or vehicle every other day starting at day 6 and throughout the experiment. Mice were sacrificed for analysis at day 13–16 post EAE induction.

(A) IFN-β treatment increases BAFF in serum from mice with EAE. Serum BAFF concentrations were determined at EAE day 16 in IFN-β (N=5) or vehicle (N=5) treated mice by ELISA. The error bars represent S.E.M. and two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used to determine significance (**p<0.01).

(B) IFN-β treatment increases splenic B cell numbers in mice with EAE. Absolute B cell numbers were determined at EAE day 16 in mice receiving IFN-β (N=6) or vehicle (N=6) treatment mice by manual hemocytometer counts and FACS analysis. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used to determine statistical significance (**p<0.01) and error bars represent S.E.M.

(C–G) IFN-β alters B cell subsets in spleens from mice with EAE. Absolute numbers of (C) CD19+IgMhiIgDloCD21-CD23- transitional 1 and CD19+IgMhiIgDloCD21-CD23+ transitional 2 B cells, (D) CD19+IgDloCD21hi and CD19+IgD+IgMhiCD21hi marginal zone B cells, (E) CD19+IgD+CD21int Follicular B cells, (F) CD19+CD23loCD5+CD1DhiIgMhi regulatory B cells, and (G) CD138+B220loCD19loCD267int plasma cells were assessed in spleens from EAE mice treated with IFN-β (N=3) or vehicle (N=3) by flow cytometry. Two-tailed Student’s t-test were used to determine statistical significance (*p<0.05, **p<0.01) and error bars represent S.E.M. (H) IFN-β elevates of transitional B cells is confirmed by measurement of AA4.1+CD19+ B cells in peripheral blood from EAE mice. Representative FACS plots of blood cells from EAE mice treated with IFN-β or vehicle at EAE day 16.

(I) Peripheral B cell numbers are inversely correlated with EAE severity despite MOG autoantibody production. Negative correlation between EAE scores and the percentage of CD19+ cells in the spleens EAE mice. Using linear regression we determined the slope was non-zero with the indicated R2 and the statistical significance was indicated as a p value. Data are representative of IFN-β treated and vehicle treated mice (N=10 total) from 2 pooled experiments.

Figure 5.

B cells are required for therapeutic efficacy of IFN-β treatment EAE. EAE was induced in WT (A) and muMT (B) mice and treated with IFN-β (10,000U/dose) or vehicle every other day starting at day 6 until day 20 (treatment initiation and cessation indicated by arrows). WT Veh N=15, WT IFN-β N=14, muMT Veh N=6, muMT IFN-β N=6. Statistics were determined by a Mann-Whitney (*p<0.05) and error bars represent S.E.M. These data are combined from three independent experiments. (C) Histology of spinal cords isolated from WT and muMT mice treated with IFN-β or vehicle. Mice were sacrificed at EAE day 13 and tissue harvested and stained with both H&E and Luxol fast blue. (D) Spinal cord infiltrating CD4+ T-cells and CD19+ B cells were assessed by flow cytometry. WT Veh n=6, WT IFN-β n=5, muMT Veh n= 3, muMT IFN-β= 3. Statistical significance was determined by one-way anova. (E) IFN-β treatment elevates IL-10 in spleen cells from wild type mice. Spleen cells from WT and muMT mice treated with IFN-β or vehicle were cultured with 1 ug/ml of MOG35-55 for 72 hrs and IL-10 was measured in the culture supernatants by ELISA. Statistics were determined by one-way anova.

Effect of IFN-β treatment on the development of auto-reactive antibodies

Since, IFN-β increased BAFF and altered B cell populations in both RRMS and EAE, we next assessed the effects this treatment had on the humoral immune response in EAE. We observed that IFN-β treatment of EAE significantly increased the concentration of the anti-MOG IgG but not IgM compared to vehicle treated EAE (Fig. 4A). However, unlike what we observed with B cell numbers, the increased anti-MOG IgG did not correlate with severity of the disease and occurred despite therapeutic benefit (Fig. 4B). These data provide evidence that the inflammatory injury to the CNS is not mediated by auto-antibodies in EAE and also are congruent with the observation that mice deficient in cytidine deaminase(15), an enzyme required for B cell class switching and IgG production, still develop severe EAE comparable to WT animals.

Figure 4.

(A) IFN-β treatment increases serum anti-MOG IgM and IgG autoantibodies in EAE although these antibodies do not correlate with EAE severity. Serum from EAE treated with IFN-β (N=8), vehicle (N=8) or healthy control mice (N=3) were analyzed for anti-MOG IgM and IgG by sandwich ELISAs. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used to determine statistical significance (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). (B) Linear regression between serum anti-MOG antibodies and EAE score are also displayed. R2 and p values are displayed. These data are representative of two pooled experiments.

IFN-β treatment in EAE requires B cell regulation

IFN-β signaling directly and indirectly stimulates B cell survival and there are now several reports of regulatory B cells in autoimmunity(2, 10, 12, 14, 16–18). Yet, whether the effect IFN-β has on B cells is incidental, promotes inflammation, or regulates cell-mediated CNS injury is unknown. To address this question directly, we compared IFN-β treatment of EAE induced in both WT and muMT mice, which are unable to produce surface IgM and have an arrest in the maturation of B cells in the bone marrow(19). In contrast to WT mice (Fig. 5A), we found that treatment with IFN-β was unable to reduce disease severity in the muMT (Fig. 5B). Histopathology and FACS analysis confirmed the clinical scores (Fig. 5D and C). IFN-β treatment reduced numbers of infiltrating CD4 T-cells (Fig. 5D) and reduced the number and size of inflammatory lesions in the spinal cords of WT mice (Fig. 5C). In contrast, muMT mice had no observable reduction in the CD4 cell infiltration and lesions load when treated with IFN-β (Fig. 5C and D). Finally, we found that 1 ug/ml of MOG peptide stimulation induced spleen cells from IFN-β treated WT mice (EAE score of 0) to produce significantly more IL-10 compared to vehicle treated WT mice (EAE score of 3) and muMT mice treated with IFN-β (EAE score of 3) or vehicle (EAE score of 3) (Fig 5E). These data provide strong evidence that IFN-β treatment of EAE requires regulatory B cell function.

IFN-β treatment in EAE maintains the population of transient regulatory B cells

Recent reports demonstrate that transfer of terminally differentiated, antigen experienced regulatory B cells can inhibit EAE and other mouse autoimmunity on adoptive transfer, however the CD19+CD23loCD5+CD1DhiIgMhi B cell has a transient regulatory function and differentiates to plasma cells when transferred into recipient mice(12, 17, 20). To address whether IFN-β treatment induces a transient or a terminally differentiated regulatory B cell subset, we isolated B220+ B cells from the spleens from WT EAE mice treated with IFN-β or vehicle and transferred 20×106 B cells into treatment naive EAE mice 6 days post immunization and tracked the development of paralysis. We found that the progression of EAE did not differ in mice receiving either PBS, B cells from IFN-β treated mice or B cells from vehicle treated mice (Fig. 6). These data demonstrate that IFN-β treatment does not induce a terminally differentiated regulatory B cell but rather maintains a population of transitional B cells that have a regulatory function.

Figure 6.

Adoptive transfer of B cells from IFN-β treated EAE does not protect mice from EAE. Effect of adoptively transferred B cells on EAE. 20×106 B220+ cells from either IFN-β (N=7) or vehicle treated mice (N=5) were transferred into recipient mice on EAE day 6 (injection of B cells indicated by arrow). EAE progression was compared to mice that did not receive B cells (N=3).

Discussion

Understanding the mechanisms behind effective IFN-β therapy of RRMS is still an active area of research. Reports have demonstrated that IFN-β alters chemokine production by myeloid cells to inhibit EAE and more recently it has been shown that IFN-β treatment also generates a novel regulatory T-cell subset to inhibit disease(7, 8). In contrast to RRMS, type I IFNs have an opposing role in other autoimmune diseases, such as SLE and NMO. In SLE, endogenous type I IFN drives disease flares and in NMO IFN-β treatment induces relapses. This paradoxical role of type I IFN in RRMS compared to SLE and NMO is also mirrored by the function BAFF and APRIL play in these diseases. Benlysta, an anti-BAFF antibody, and high dose atacicept, a TACI-Ig fusion protein that blocks BAFF and APRIL, have both been effective in reducing SLE flares(21, 22). This is in stark contrast to RRMS, where atacicept worsened disease activity in RRMS patients(23).

Our data, taken in the context of other reports, suggest a therapeutic mechanism of IFN-β that bridges the opposing effects IFN-β and BAFF blockers have in RRMS. Recently it has been shown that IFN-β treatment induces the expression of BAFF in myeloid cells from RRMS patients(4, 24–26). Strikingly, myeloid cells require type I IFN signaling to attenuate EAE(8). In this manuscript, we show in both RRMS patients and EAE mice that IFN-β treatment increases serum BAFF levels and maintains high numbers of a transient regulatory/transitional B cells, a population of B cells that requires BAFF signaling for their development(27). Furthermore, we directly show that IFN-β treatment of EAE requires B cell regulation to attenuate cell-mediated CNS injury. Therefore we propose the following mechanistic model. Treatment with IFN-β induces BAFF expression in myeloid cells, which in turn promote the expansion of transitional B cells. These transitional B cells have a regulatory function in autoimmune diseases and are capable of producing large amounts of IL-10 to suppress antigen mediated T-cell activity in healthy individuals. Remarkably, in SLE transitional B cells induce effector T-cell responses and are likely pro-inflammatory(10). Taken together, these data suggest that in RRMS patients IFN-β increases BAFF expression, and unlike in SLE and NMO, skews the B cell population toward a regulatory phenotype.

Anti-CD20 therapy, such as rituximab, is remarkably effective in RRMS. This may seem to contradict our model. Yet, rituximab therapy has been shown to elevate BAFF levels in patients and regulatory transitional B cells are preferentially expanded after anti-CD20 therapy(28), similar to what we found in IFN-β treated RRMS suggesting a possibly convergent mechanism. We hypothesize that a subset of RRMS patients who fail IFN-β therapy have pathogenic B cell responses or inadequate activation of regulatory B cell activity. Future studies should evaluate how serum markers of B cell activation during IFN-β therapy correlate with treatment outcome. While our exploratory clinical data meets statistical significance, we present a small sample size of patients and controls. To validate our findings, we are in the process of preparing a larger, longitudinal cohort study.

The work presented here complements a growing body of literature on the complexity of B cells in human autoimmunity, and provides evidence for the first time that IFN-β therapy stimulates a regulatory B cell in RRMS. This has implications for the monitoring and treatment of RRMS patients treated with IFN-β. From the standpoint of discovery based research, future work should evaluate more directly the contribution BAFF and APRIL have on IFN-β’s therapeutic effect.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the OMRF imaging core for the immunohistochemistry.

Footnotes

This study was primarily funded by an NIH grant to RCA: R00 NS075099-04. The MS bio-repository at OMRF was supported by an NIH COBRE grant: P30 GM103510; an OSCTR Grant: U54 GM104938; and an ACE Grant: U19 AI082714.

References

- 1.Feng X, Reder NP, Yanamandala M, Hill A, Franek BS, Niewold TB, Reder AT, Javed A. Type I interferon signature is high in lupus and neuromyelitis optica but low in multiple sclerosis. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2012;313:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiefer K, Oropallo MA, Cancro MP, Marshak-Rothstein A. Role of type I interferons in the activation of autoreactive B cells. Immunology and cell biology. 2012;90:498–504. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palace J, Leite MI, Nairne A, Vincent A. Interferon Beta treatment in neuromyelitis optica: increase in relapses and aquaporin 4 antibody titers. Archives of neurology. 2010;67:1016–1017. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krumbholz M, Faber H, Steinmeyer F, Hoffmann LA, Kumpfel T, Pellkofer H, Derfuss T, Ionescu C, Starck M, Hafner C, Hohlfeld R, Meinl E. Interferon-beta increases BAFF levels in multiple sclerosis: implications for B cell autoimmunity. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2008;131:1455–1463. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanotti C, Chiarini M, Serana F, Capra R, Rottoli M, Rovaris M, Cavaletti G, Clerici R, Rezzonico M, Caimi L, Imberti L. Opposite effects of interferon-beta on new B and T cell release from production sites in multiple sclerosis patients. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2011;240–241:147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panitch H, Goodin D, Francis G, Chang P, Coyle P, O’Connor P, Li D, Weinshenker B, Group ES MS MR IR G the University of British Columbia. Benefits of high-dose, high-frequency interferon beta-1a in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis are sustained to 16 months: final comparative results of the EVIDENCE trial. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2005;239:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Carlsson R, Comabella M, Wang J, Kosicki M, Carrion B, Hasan M, Wu X, Montalban X, Dziegiel MH, Sellebjerg F, Sorensen PS, Helin K, Issazadeh-Navikas S. FoxA1 directs the lineage and immunosuppressive properties of a novel regulatory T cell population in EAE and MS. Nature medicine. 2014;20:272–282. doi: 10.1038/nm.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prinz M, Schmidt H, Mildner A, Knobeloch KP, Hanisch UK, Raasch J, Merkler D, Detje C, Gutcher I, Mages J, Lang R, Martin R, Gold R, Becher B, Bruck W, Kalinke U. Distinct and nonredundant in vivo functions of IFNAR on myeloid cells limit autoimmunity in the central nervous system. Immunity. 2008;28:675–686. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalled SL. Impact of the BAFF/BR3 axis on B cell survival, germinal center maintenance and antibody production. Seminars in immunology. 2006;18:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blair PA, Norena LY, Flores-Borja F, Rawlings DJ, Isenberg DA, Ehrenstein MR, Mauri C. CD19(+)CD24(hi)CD38(hi) B cells exhibit regulatory capacity in healthy individuals but are functionally impaired in systemic Lupus Erythematosus patients. Immunity. 2010;32:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avery DT, Ellyard JI, Mackay F, Corcoran LM, Hodgkin PD, Tangye SG. Increased expression of CD27 on activated human memory B cells correlates with their commitment to the plasma cell lineage. Journal of immunology. 2005;174:4034–4042. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maseda D, Smith SH, DiLillo DJ, Bryant JM, Candando KM, Weaver CT, Tedder TF. Regulatory B10 cells differentiate into antibody-secreting cells after transient IL-10 production in vivo. Journal of immunology. 2012;188:1036–1048. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsushita T, Fujimoto M, Hasegawa M, Komura K, Takehara K, Tedder TF, Sato S. Inhibitory role of CD19 in the progression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by regulating cytokine response. The American journal of pathology. 2006;168:812–821. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshizaki A, Miyagaki T, DiLillo DJ, Matsushita T, Horikawa M, Kountikov EI, Spolski R, Poe JC, Leonard WJ, Tedder TF. Regulatory B cells control T-cell autoimmunity through IL-21-dependent cognate interactions. Nature. 2012;491:264–268. doi: 10.1038/nature11501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galicia G, Boulianne B, Pikor N, Martin A, Gommerman JL. Secondary B cell receptor diversification is necessary for T cell mediated neuro-inflammation during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. PloS one. 2013;8:e61478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landolt-Marticorena C, Wither R, Reich H, Herzenberg A, Scholey J, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Fortin PR, Wither J. Increased expression of B cell activation factor supports the abnormal expansion of transitional B cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of rheumatology. 2011;38:642–651. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsushita T, Yanaba K, Bouaziz JD, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. Regulatory B cells inhibit EAE initiation in mice while other B cells promote disease progression. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:3420–3430. doi: 10.1172/JCI36030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Deriaud E, Jiao X, Braun D, Leclerc C, Lo-Man R. Type I interferons protect neonates from acute inflammation through interleukin 10-producing B cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:1107–1118. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitamura D, Roes J, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. A B cell-deficient mouse by targeted disruption of the membrane exon of the immunoglobulin mu chain gene. Nature. 1991;350:423–426. doi: 10.1038/350423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe R, Ishiura N, Nakashima H, Kuwano Y, Okochi H, Tamaki K, Sato S, Tedder TF, Fujimoto M. Regulatory B cells (B10 cells) have a suppressive role in murine lupus: CD19 and B10 cell deficiency exacerbates systemic autoimmunity. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:4801–4809. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O, Cervera R, Wallace DJ, Tegzova D, Sanchez-Guerrero J, Schwarting A, Merrill JT, Chatham WW, Stohl W, Ginzler EM, Hough DR, Zhong ZJ, Freimuth W, van Vollenhoven RF, Group B-S. A phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2011;63:3918–3930. doi: 10.1002/art.30613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isenberg D, Gordon C, Licu D, Copt S, Rossi CP, Wofsy D. Efficacy and safety of atacicept for prevention of flares in patients with moderate-to-severe systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): 52-week data (APRIL-SLE randomised trial) Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2014 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-205067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kappos L, Hartung HP, Freedman MS, Boyko A, Radu EW, Mikol DD, Lamarine M, Hyvert Y, Freudensprung U, Plitz T, van Beek J, Group AS. Atacicept in multiple sclerosis (ATAMS): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet neurology. 2014;13:353–363. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krumbholz M, Derfuss T, Hohlfeld R, Meinl E. B cells and antibodies in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis and therapy. Nature reviews. Neurology. 2012;8:613–623. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scapini P, Hu Y, Chu CL, Migone TS, Defranco AL, Cassatella MA, Lowell CA. Myeloid cells, BAFF, and IFN-gamma establish an inflammatory loop that exacerbates autoimmunity in Lyn-deficient mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207:1757–1773. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scapini P, Nardelli B, Nadali G, Calzetti F, Pizzolo G, Montecucco C, Cassatella MA. G-CSF-stimulated neutrophils are a prominent source of functional BLyS. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;197:297–302. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rickert RC, Jellusova J, Miletic AV. Signaling by the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily in B-cell biology and disease. Immunological reviews. 2011;244:115–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palanichamy A, Barnard J, Zheng B, Owen T, Quach T, Wei C, Looney RJ, Sanz I, Anolik JH. Novel human transitional B cell populations revealed by B cell depletion therapy. Journal of immunology. 2009;182:5982–5993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.