Abstract

Angiogenesis is regulated by chemical and mechanical factors in vivo. The regulatory role of mechanical factors and how chemical and mechanical angiogenic regulators work in concert remains to be explored. We investigated the effect of cyclic uniaxial stretch (20%, 1 Hz), with and without the stimulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), on sprouting angiogenesis by employing a stretchable 3-dimensional cell culture model. When compared to static controls, stretch alone significantly increased the density of endothelial sprouts, and these sprouts aligned perpendicular to the direction of stretch. The Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Y27632 suppressed stretch-induced sprouting angiogenesis and associated sprout alignment. While VEGF is a potent angiogenic stimulus through ROCK-dependent pathways, the combination of VEGF and stretch did not have an additive effect on angiogenesis. In the presence of VEGF stimulation, the ROCK inhibitor suppressed stretch-induced sprout alignment but did not affect stretch-induced sprout density; in contrast, the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor sunitinib had no effect on stretch-induced alignment but trended toward suppressed stretch-induced sprout density. Our results suggest that the formation of sprouts and their directionality do not have completely identical regulatory pathways, and thus it is possible to separately manipulate the number and pattern of new sprouts.

Keywords: Cyclic uniaxial stretch, vascular endothelial growth factor, Rho-associated kinase, receptor tyrosine kinase, mechanotransduction

INTRODUCTION

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been shown to be a key regulator of angiogenesis. The effect of VEGF on angiogenesis is primarily mediated by VEGF receptors VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, which are expressed on vascular endothelial cells (ECs).1 As part of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) superfamily, VEGF receptors undergo ligand-induced dimerization as a means to receptor activation.2 VEGF receptor activation triggers downstream signaling pathways that are an integral part of migration and proliferation in angiogenesis.3 Although the exact mechanism by which these signaling pathways induce angiogenesis is complex and not yet fully understood, the small GTPase RhoA and its downstream effector Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) have been shown to be essential mediators of VEGF-induced angiogenesis in several in vivo and in vitro studies (see4,5 for review). Recent research showed that negative and positive manipulation of RhoA activity (by negative and positive RhoA mutants, respectively) can suppress and promote, respectively, blood vessel formation in vivo and in vitro.6 Further in vivo work has shown that RhoA/ROCK is central to mediating VEGF-induced angiogenesis in mice.7 Additionally, in vitro models have indicated the dependence of VEGF-induced angiogenesis on RhoA/ROCK signaling.7,8 Because VEGF plays a crucial role as a pro-angiogenic agent, various VEGF-based therapies have been developed to treat disease via manipulating angiogenesis, such as anti-VEGF therapies to inhibit angiogenesis and thereby minimize tumor growth or pro-VEGF therapies to enhance angiogenesis and thereby treat cardiovascular disease.2,9

In addition to VEGF and other chemical regulators, blood flow associated hemodynamic factors and tissue movement associated mechanical loading have also emerged for their essential role in regulating angiogenesis.10 In vivo studies have shown that changes in blood flow and global tissue or muscle stretching can induce angiogenesis in skeletal muscle,11,12 though it is difficult to dissect the effect of cyclic stretch from the numerous angiogenic factors present in vivo or to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms. Many in vitro studies have revealed that uniaxial and biaxial cyclic stretch of ECs directly affects many cell activities that are involved in angiogenesis, including increased cell migration, expanded cell proliferation, and vascular patterning.13–16 On a mechanistic level, although the role of RhoA/ROCK signaling in stretch-induced angiogenesis remains not yet completely understood, uniaxial17 and biaxial18 stretch has been shown to reorganize the actin cytoskeleton in a RhoA/ROCK dependent manner in vitro. Additionally, RhoA/ROCK signaling has been shown to play a significant role in biaxial stretch-induced proliferation in ECs in vitro.19 Furthermore, RhoA signaling may play a significant part in both biaxial stretch- and VEGF-induced EC permeability in vitro.20

The purpose of this study is to investigate the interplay of cyclic uniaxial stretch and VEGF in the regulation of angiogenesis and to elucidate the role of RhoA/ROCK signaling within this relationship by way of a novel, stretchable 3-D angiogenesis in vitro model. In addition, we seek to define the role RTKs may play in this signaling. These results can then be used to develop efficacious specific therapeutic options to control angiogenesis, particularly in conditions subject to the impact of cyclic stretch.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Reagents were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) unless otherwise noted. Bovine aortic ECs (BAECs) (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) were cultured in high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 2% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% sodium pyruvate. Cell culture was maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2/95% air incubator. Experiments used cell passages eight through thirteen.

Cyclic stretch experiments

The effects of cyclic stretch on sprouting angiogenesis were examined using a stretchable 3-D angiogenesis model, as previously described.13,21 Briefly, BAECs were seeded at 6×104 cells/cm2 atop a DMEM-conditioned collagen gel (3 mg/ml bovine dermal collagen type I; Advanced Biomatrix, San Diego, CA) constrained in a custom silicone mold (treated with sulfuric acid to prevent gel contraction and shrinkage during experimentation) and cultured in supplemented DMEM in an incubator. The cells reached confluence 3 days after seeding. Next, cells were incubated for 24 hr in supplemented DMEM with or without an additional 30 ng/ml VEGF (PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ) in the incubator. Following the 24-hr pretreatment period, collagen gels constrained in the silicone molds were kept as static controls or exposed to cyclic uniaxial stretch (20%, 1 Hz) for 48 hr in a custom-made environmental chamber maintained at 37°C with humidified 5% CO2/95% air. For samples that were exposed to an additional 30 ng/ml VEGF during the 24-hr pretreatment period, VEGF was present throughout the 48-hr stretch experiments.

Inhibitor studies

For ROCK inhibition, 1 μM Y27632 (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA), a specific ROCK inhibitor,22 was added to the supplemented DMEM 30 min prior to stretching. The inhibitor was either present throughout the 48-hr cyclic stretch experiments or removed just prior to stretching by washing once with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and replacing with fresh supplemented medium without inhibitor. For RTK inhibition, 0.1 μM sunitinib (LC Labs, Woburn, MA), an inhibitor of various RTKs including VEGFR,23 was added to the supplemented DMEM 30 min prior to stretching and was present throughout the cyclic stretch experiments. These concentrations (1 μM for Y276328,24 and 0.1 μM for sunitinib25) were used because they have been shown to inhibit angiogenesis in static cell or organ culture experiments. Both inhibitors were added to these four groups: (1) static without additional VEGF, (2) static with additional VEGF, (3) stretch without additional VEGF, and (4) stretch with additional VEGF.

Staining

At the end of cyclic stretch experiments, cells on and within the gel were fixed using 4% paraformadehyde (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 2 hr, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 15 min, and double stained for nuclei (5 μg/ml Hoechst 33342) and actin filaments (300 U/ml Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin) for 1 hr. The gel was then mounted for microscopic observation.

Microscopic image acquisition and analysis

Microscopic image acquisition

Fluorescent images of cells on and in the collagen gel were captured using an Olympus FV-1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) and a 60x objective. Optical sections were taken every 5 μm beginning at the monolayer and proceeding down into the gel to 500 μm. Optical sections were then compiled to create 3-D reconstructions. Image post-processing and reconstructions were accomplished using both ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD) and Imaris (Bitplane AG, Zurich, Switzerland) software. Endothelial sprouts were characterized as cells below the monolayer and within the 3-D collagen gel (referred to as invasive structures). These nascent endothelial sprouts were characterized by individual cells, individual constructs made of multiple cells (nuclei) without lumens (termed cords), and anastomoses connecting cells and cords.

Quantification of cell density

The number of invasive structures in each collagen gel was determined by measuring the number of cell nuclei within the gel below monolayer cells using the Imaris software and was expressed as the number of nuclei/mm3. The densities of invasive structures in collagen gels exposed to the same treatment were then averaged. The number of monolayer cells on each collagen gel was determined by measuring the number of cell nuclei on the top surface of the gel and was expressed as the number of nuclei/mm2. The densities of monolayer cells on collagen gels exposed to the same treatment were then averaged. When inhibitors were used, fold change of monolayer and invasive cell density were determined with respect to the average number of cells in the “non-stretched, non-VEGF and non-inhibitor” treated control samples.

Quantification of cell alignment

Orientation was characterized by measuring the angle between the major axis of each invasive structure or monolayer cell with respect to the stretch direction for each collagen gel. This analysis was done as previously described,13 except that ImageJ software was used for the alignment analysis on optical sections. 0° and 90° were set to be parallel and perpendicular to the stretch direction, respectively. The invasive structures and monolayer cells were put into three groups: 0–30°, 30–60°, and 60–90°. Originally 10-degree groups were used; the bin size was then slowly increased until the clearest pattern was seen, which was in 30-degree groups. Both the average angle and the angle distribution were calculated for all invasive cells in collagen gels exposed to the same treatment, and for all monolayer cells on collagen gels exposed to the same treatment. A population of invasive structures with random alignment is expected to have an average angle that is close to 45° and an equal distribution among all 3 groups (i.e., 33.3% for each group). For a population of invasive structures that tend to align perpendicularly to the stretch direction, the average angle will be > 45° and the percentage of cells in the in the 0–30° and 60–90° groups would be < and > 33.3%, respectively.

Statistical analysis and data presentation

Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean, with n values as shown in figure legends, representing the number of collagen gels per experimental group. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP (SAS, Cary, NC). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, with significance set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Effects of cyclic uniaxial stretch on invasive and monolayer cell density

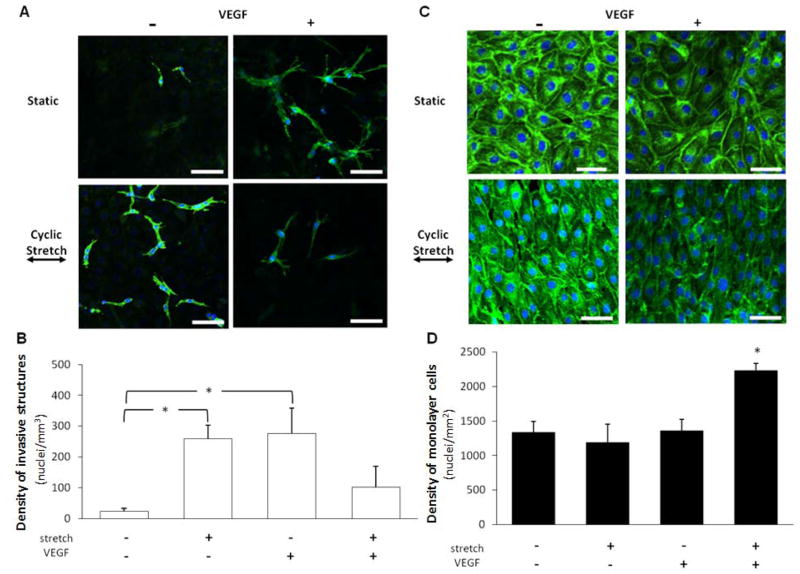

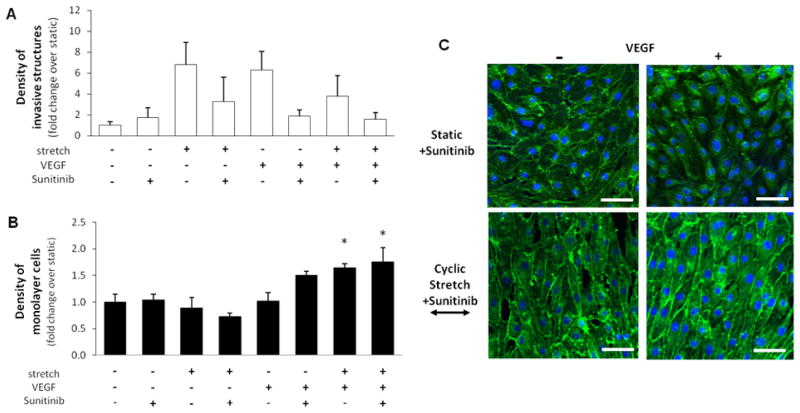

In order to determine the respective and combined effects of cyclic uniaxial stretch (20%, 1 Hz) and VEGF on sprouting angiogenesis, cells were cyclically stretched with or without VEGF stimulation for 48 hr. Next, the density of invasive and monolayer cells was determined by counting the number of cell nuclei. Representative microscopic images of invasive structures and monolayer cells in response to all conditions are shown in Figures 1A and 1C, respectively. We found that cyclic stretch alone significantly increased the invasive cell density without altering the monolayer cell density (Figures 1B,D). Using VEGF alone as a positive control, we found no significant difference between the cyclic stretch (20%, 1 Hz)-induced increase and the VEGF (30 ng/ml)-induced increase in invasive cell density (Figure 1B) or maintenance of monolayer cell density (Figure 1D). These results indicate that cyclic stretch, like VEGF, is a pro-angiogenic stimulant. The combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF significantly increased the monolayer cell density (Figure 1D), but did not have an additive effect on the invasive cell density. Previously, Yung et al. reported that a combination of cyclic uniaxial stretch (7%, 1 Hz) and VEGF (10 ng/ml) increased sprouting angiogenesis of human umbilical vein ECs.26 In their study, angiogenesis experiments were performed by embedding EC-coated micro-carriers in a fibrin gel. Whether the differences between our findings are a result of the different stretch magnitudes, VEGF concentrations, EC cell types or angiogenesis assays remain to be explored.

Figure 1. Effects of cyclic uniaxial stretch on invasive and monolayer cell density.

Cells grown to confluence atop collagen gels, with or without VEGF treatment, were subjected either to cyclic stretch (20%, 1 Hz) or kept as static controls for 48 hr. Next, the densities of invasive and monolayer cells were quantified. A. Representative images of invasive structures (mimicking nascent endothelial sprouts) inside of collagen gels. Cells were fluorescently labeled for nuclei (blue) and actin filaments (green). Scale bars in all images are 50 μm. B. Invasive cell density was significantly increased (*p<0.05) by cyclic stretch or VEGF alone. However, a combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF treatment did not result in a significant increase in invasive cell density. *p<0.05 between bracketed comparisons. C. Representative images of monolayer cells on top of collagen gels. Cells were fluorescently labeled for nuclei (blue) and actin filaments (green). Scale bars in all images are 25 μm. D. Monolayer cell density was not significantly increased by cyclic stretch or VEGF alone. However, a combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF treatment significantly increased monolayer cell density (*p<0.05). N = 6, 3, 6, 3 (from left to right at each experimental condition) in both B and D.

Cyclic uniaxial stretch induced alignment of invasive structures and monolayer cells

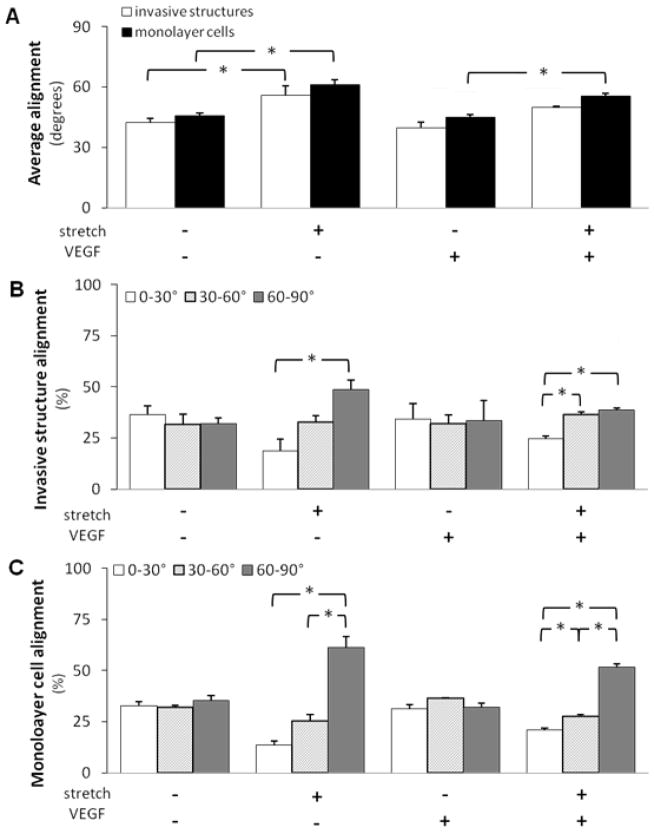

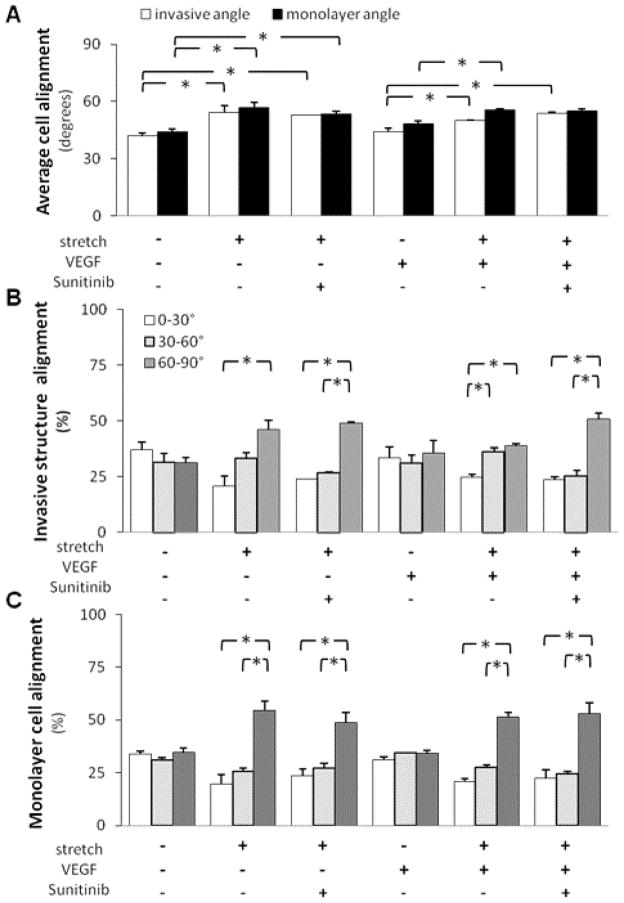

We investigated the effect of cyclic stretch on the alignment of nascent endothelial sprouts in order to understand the effect of cyclic stretch on vascular patterning or cellular orientation. As mentioned in the Materials and Methods section, we measured cell alignment by measuring the angle between the cell’s major axis and the stretch direction. 0° and 90° were set to be parallel and perpendicular to the stretch direction, respectively. The cells were then put into three groups: 0–30°, 30–60°, and 60–90°. As expected, the static controls showed random alignment, distributing equally among all 3 groups. We found that cyclic stretch alone induced a statistically significant increase in the average angle (Figure 2A) and the percentage of cells in the 60–90° group (Figures 2B, C) of both invasive structures and monolayer cells, suggesting that these cells tended to align perpendicular to the direction of stretch. As expected, VEGF stimulation alone did not significantly alter the average angle or angle distribution of invasive structures or monolayer cells when compared to the static and non-VEGF controls. Additionally, VEGF stimulation did not affect the stretch-induced increase in the average angle. The average angles of invasive structures for stretch samples and combined stretch and VEGF samples were 56.0±4.7 and 50.0±0.5 degrees (p>0.05), respectively. The average angles of monolayer cells for stretch samples and combined stretch and VEGF samples were 61.3±2.3 and 55.3±1.5 degrees (p>0.05), respectively.

Figure 2. Cyclic uniaxial stretch induced a perpendicular alignment of both invasive structures and monolayer cells.

Cells grown to confluence atop collagen gels, with or without VEGF treatment, were subjected either to cyclic stretch (20%, 1 Hz) or kept as static controls for 48 hr. Next, the alignment (measured by angles) of invasive structures and monolayer cells was quantified. 0° and 90° were set to be parallel and perpendicular to the stretch direction, respectively. The invasive structures and monolayer cells were put into three groups: 0–30°, 30–60°, and 60–90°. A. Cyclic stretch significantly increased the average angles of monolayer cells when compared to static controls, irrespective of the presence or absence of VEGF treatment (*p<0.05). Cyclic stretch significantly increased the average angles of invasive structures when compared to static controls in the absence of VEGF treatment (*p<0.05). B. Under cyclic stretch, the percentage of invasive structures aligned the most perpendicular to the stretch direction (60–90°) was significantly higher than the percentage of invasive structures aligned parallel to the stretch direction (0–30°) (*p<0.05). A combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF treatment also induced such a preferential alignment (*p<0.05). C. Under cyclic stretch, the percentage of monolayer cells aligned the most perpendicular to the stretch direction (60–90°) was significantly higher than the percentage of monolayer cells aligned parallel to the stretch direction (0–30°) (*p<0.05). This increase was irrespective of the presence or absence of VEGF treatment for monolayer cells. *p<0.05 between bracketed comparisons. N = 4, 3, 4, 3 (from left to right at each experimental condition) in A and B for invasive structures. N = 5, 3, 4, 3 (from left to right at each experimental condition) in A and C for monolayer cells.

Effects of ROCK inhibition on cyclic uniaxial stretch-mediated invasive and monolayer cell density

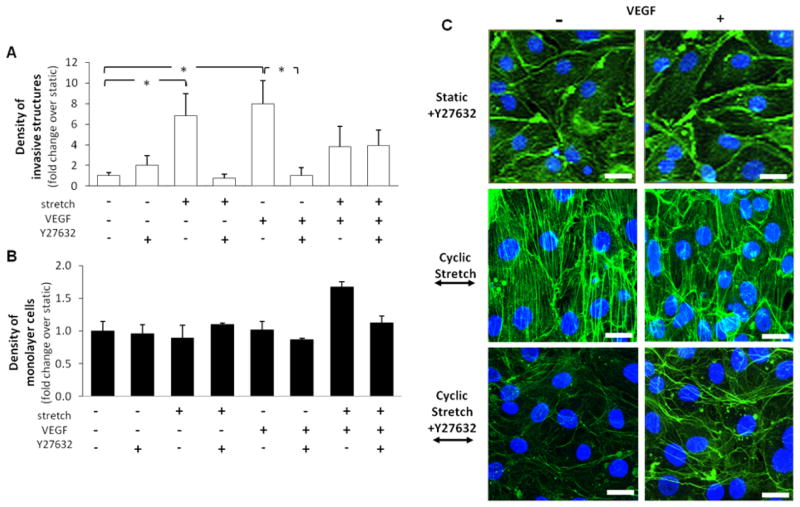

Y27632, a selective ROCK inhibitor, was used to determine the role of ROCK in cyclic stretch-mediated sprouting angiogenesis. Representative images of stretched monolayer cells with and without VEGF and/or ROCK inhibitors are shown in Figure 3C. The presence of Y27632 throughout experimentation trended toward mitigating the significant increase in invasive cell density induced by cyclic stretch alone (Figure 3A). A similar pattern was seen for VEGF-induced angiogenesis, where the ROCK inhibitor significantly reduced the density of invasive cells induced by VEGF alone (Figure 3A). These results suggest an important role for ROCK in either cyclic stretch or VEGF-induced angiogenesis. In contrast, this reduction effect was not observed in samples exposed to the combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF treatment (Figure 3A). We also found that the presence of Y27632 did not affect the monolayer density under cyclic stretch or VEGF alone, but trended toward eradicating the significant increase in the monolayer cell density of samples exposed to the combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF treatment (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Effects of ROCK inhibition on cyclic uniaxial stretch-mediated invasive and monolayer cell density.

Cells grown to confluence atop collagen gels, with or without VEGF treatment, were subjected either to cyclic stretch (20%, 1 Hz) or kept as static controls for 48 hr. 1 μM Y27632 (for ROCK inhibition) was added to the medium 30 min prior to stretch and remained for the following 48 hr. Next, the densities of invasive and monolayer cells were quantified, and normalized to that of the “static, no VEGF and no Y27632” control. A. ROCK inhibition trended toward eradicating the cyclic stretch-mediated increase in invasive cell density. ROCK inhibition also nullified the VEGF-mediated increase in invasive cell density (*p<0.05). In contrast, ROCK inhibition did not affect the invasive cell density of samples exposed to the combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF treatment. *p<0.05 between bracketed comparisons. B. ROCK inhibition trended toward eradicating the significant increase in monolayer density for samples exposed to the combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF treatment. C. Representative images of monolayer cells exposed to cyclic stretch for 48 hr, with or without the treatment of VEGF stimulation or ROCK inhibition. Cells were fluorescently labeled for nuclei (blue) and actin filaments (green). The perpendicular alignment of cells and actin stress fibers to the stretch direction is evident in samples exposed to stretch both in the presence and absence of VEGF treatment. ROCK inhibition nullified this response. Scale bars in all images are 15 μm. N = 9, 3, 6, 3, 9, 3, 6, 3 (from left to right at each experimental condition) in both A and B.

ROCK is required for stretch-induced alignment of invasive structures and monolayer cells

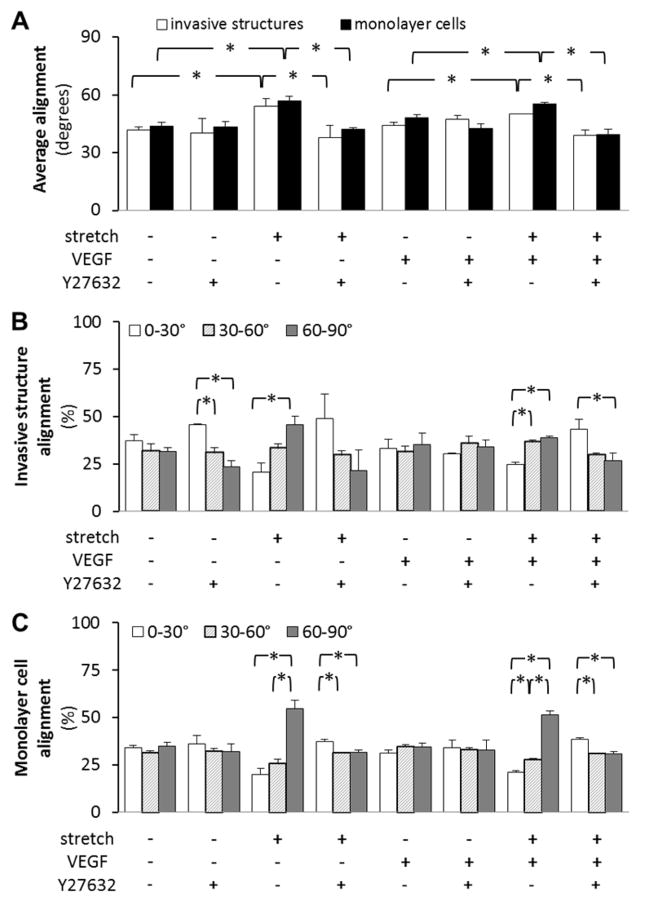

We investigated the effect of ROCK inhibition on cyclic stretch-induced alignment of both monolayer cells and invasive structures. ROCK inhibition throughout experimentation was found to eliminate the preferential cell orientation in response to cyclic stretch for both invasive structures and monolayer cells (Figure 4). The average angles of invasive structures for stretch samples and combined stretch and Y27632 samples were 54.2±3.8 and 37.8±6.1 degrees (p<0.05), respectively. The average angles of monolayer cells for stretch samples and combined stretch and Y27632 samples were 56.7±2.6 and 42.2±0.9 degrees (p<0.05), respectively. These results suggest that ROCK is required for perpendicular cellular alignment in response to cyclic uniaxial stretch both in both 3-D (invasive structures) and 2-D (monolayer cells) settings. Additionally, ROCK inhibition was found to eliminate the perpendicular alignment of both invasive structures and monolayer cells exposed to a combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF stimulation (Figure 4).

Figure 4. ROCK inhibition mitigated cyclic uniaxial stretch-induced alignment of invasive structures and monolayer cells.

Cells grown to confluence atop collagen gels, with or without VEGF treatment, were subjected either to cyclic stretch (20%, 1 Hz) or kept as static controls for 48 hr. 1 μM Y27632 (for ROCK inhibition) was added to the medium 30 min prior to stretch and remained for the following 48 hr. Next, the alignment (measured by angles) of invasive structures and monolayer cells was quantified. 0° and 90° were set to be parallel and perpendicular to the stretch direction, respectively. The invasive structures and monolayer cells were put into three groups: 0–30°, 30–60°, and 60–90°. A. Average angles. B. and C. Angle distributions of invasive structures and monolayer cells, respectively. ROCK inhibition eliminated the cyclic stretch-mediated perpendicular alignment of invasive structures and monolayer cells, irrespective to the presence or absence of VEGF. *p<0.05 between bracketed comparisons. N = 5, 3, 4, 3, 6, 3, 6, 3 (from left to right at each experimental condition) in A and B for invasive structures. N = 8, 3, 6, 3, 8, 3, 6, 3 (from left to right at each experimental condition) in A and C for monolayer cells.

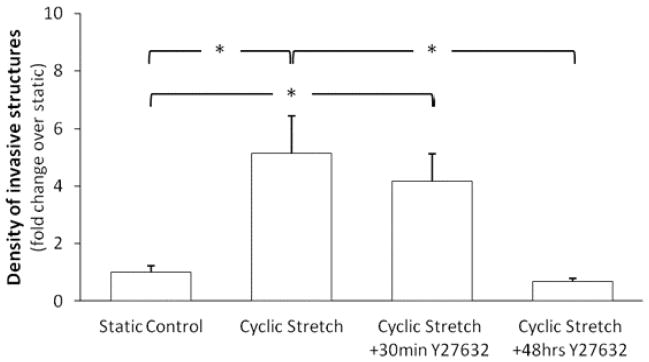

Effects of ROCK inhibition are dependent upon inhibitor exposure duration

Following the discovery that ROCK is a central component in mediating cyclic stretch-induced sprouting angiogenesis and related orientation, the effects of inhibitor exposure duration were examined. Cells without VEGF stimulation were subjected to cyclic stretch either following “30 min of inhibitor incubation and subsequent removal” or with the inhibitor present for the same incubation period as well as throughout the 48 hr of stretching. 30 minutes of inhibitor incubation alone did not suppress the significant increase in invasive cell density in response to cyclic stretch (Figure 5). 30 minutes of inhibitor incubation alone also did not affect the preferential alignment of either invasive structures or monolayer cells perpendicular to the direction of stretch. The average angles of invasive structures for stretch samples and combined stretch and 30min Y27632 samples were 55.2±6.8 and 60.0±8.4 degrees (p>0.05), respectively. The average angles of monolayer cells for stretch samples and combined stretch and 30min Y27632 samples were 72.4±15.8 and 72.3±9.0 degrees (p>0.05), respectively. Continuing inhibitor incubation for 48 hr significantly suppressed stretch-induced increase in invasive cell density (Figure 5). Thus, the inhibitive effect of ROCK inhibitors on cyclic stretch-induced invasive structure development may be dependent upon a sustained presence of the ROCK inhibitor.

Figure 5. Effects of ROCK inhibition are dependent on inhibitor exposure duration.

Cells grown to confluence atop collagen gels, without VEGF treatment, were subjected to cyclic stretch (20%, 1 Hz) or kept as static controls for 48 hr. 1 μM Y27632 (for ROCK inhibition) was added to the medium 30 min prior to stretch only (30min Y27632) or remained for the duration of the 48 hr stretch experiment (48hr Y27632). The densities of invasive structures developed under various conditions were normalized to that of the “static and no Y23672” control. 30 minutes of ROCK inhibition did not have any effect on the cyclic stretch-mediated increase in invasive cell density. However, the prolonged ROCK inhibition nullified the cyclic stretch-mediated increase in invasive cell density. N = 10, 6, 3, 3 (from left to right at each experimental condition).

Effects of RTKs on angiogenesis mediated by cyclic stretch and VEGF

Following the discovery that cyclic stretch alone- or VEGF alone-induced angiogenesis is mediated by ROCK, but not in the combination of the two factors, we explored the role of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) in angiogenesis induced by either factor alone or in the combined factors. With a stretchable 3-D angiogenesis model, cells were subjected to 48 hr of cyclic stretch or left as static controls. The importance of RTKs on invasive cell density and associated alignment in sprouting angiogenesis were examined by treating samples with 0.1 μM sunitinib for 30 min prior to stretch, which remained for the duration of the 48 hr stretch experiments. Representative images of stretched monolayer cells with and without VEGF and/or sunitinib are shown in Figure 6C. As expected, RTK inhibition trended toward a reduction in the VEGF alone-induced increase in invasive cell density (Figure 6A). Although RTK inhibition reduced stretch alone-induced angiogenesis by approximately 50%, this reduction was not statistically significant. Similarly, RTK inhibition reduced invasive cell density for samples exposed to the combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF but this reduction was not statistically significant.

Figure 6. RTK inhibition decreased cyclic uniaxial stretch-induced invasive cell density.

Cells grown to confluence atop collagen gels, with or without VEGF treatment, were subjected either to cyclic stretch (20%, 1 Hz) or kept as static controls for 48 hr. 0.1 μM sunitinib (for inhibition of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs)) was added to the medium 30 min prior to stretch and remained for the following 48 hr. Next, the density and alignment of invasive cells were quantified. The density was normalized to that of the “static, no VEGF and no sunitinib” control. A. When compared to the VEGF only treatment, RTK inhibition significantly reduced the VEGF-induced increase in invasive cell density (*p<0.05) as expected, and also significantly reduced invasive cell density for samples exposed to the combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF treatment (*p<0.05). Although not statistically significant, RTK inhibition reduced the stretch-induced increase in invasive cell density by approximately 50%. Taken together, these results suggest the importance of RTK signaling in the cyclic stretch- and VEGF-induced increase in invasive cell density. *p<0.05 between bracketed comparisons. B. RTK inhibition significantly increased monolayer cell density of samples treated with VEGF only. Note that, the combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF increased the monolayer cell density (as mentioned in Figure 1D) and RTK inhibition did not affect this increase. *p<0.05 compared to all other conditions without *. C. Representative images of monolayer cells after 48 hr RTK inhibition. Cells were fluorescently labeled for nuclei (blue) and actin filaments (green). The perpendicular alignment of cells and actin stress fibers to the stretch direction is evident in samples exposed to cyclic stretch. Scale bars in all images are 25 μm. N = 9, 8, 6, 3, 8, 6, 6, 3 (from left to right at each experimental condition) in A and N = 6, 4, 6, 3, 5, 6, 5, 3 (from left to right at each experimental condition) in B.

As mentioned above, the combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF increased monolayer cell density, which was inhibited by ROCK inhibitors (Figure 3B). Here we found that RTK inhibition did not affect the significant increase in monolayer cell density induced by the combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF (Figure 6B). Taken together, our data suggest that the inductive effect of combined stretch and VEGF on the density of monolayer cells is through a ROCK-dependent but RTK independent pathway.

Finally, we also found that RTK inhibition did not alter the significant increase in cyclic stretch-mediated perpendicular alignment of invasive structures or monolayer cells (Figure 7). Thus, the cyclic stretch-induced cell alignment is independent of RTK.

Figure 7. RTK inhibition did not alter the significant increase in cyclic uniaxial stretch-mediated perpendicular alignment of invasive structures or monolayer cells.

Here the effect of sunitinib on stretch-induced cell alignment was examined in the absence and presence of additional VEGF. Cells grown to confluence atop collagen gels, with or without VEGF treatment, were subjected either to cyclic stretch (20%, 1 Hz) or kept as static controls for 48 hr. 0.1 μM sunitinib (for RTK inhibition) was added to the medium 30 min prior to stretch and remained for the following 48 hr. Next, the alignment (measured by angles) of invasive structures and monolayer cells was quantified. 0° and 90° were set to be parallel and perpendicular to the stretch direction, respectively. The invasive structures and monolayer cells were put into three groups: 0–30°, 30–60°, and 60–90°. A. Average angles. B. and C. Angle distributions of invasive structures and monolayer cells, respectively. RTK inhibition did not affect the cyclic stretch-mediated perpendicular alignment of invasive structures and monolayer cells, irrespective to the presence or absence of VEGF. *p<0.05 between bracketed comparisons. N = 5, 4, 3, 6, 6, 3 (from left to right at each experimental condition) in A and B for invasive structures. N = 8, 6, 3, 9, 6, 3 (from left to right at each experimental condition) in A and C for monolayer cells.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we discovered that cyclic stretch induced sprouting angiogenesis and elucidated the underlying molecular mechanisms. The major new findings include: (1) Cyclic stretch alone is a potent pro-angiogenic factor and increases the number of new sprouts by ROCK-dependent pathways. While it is known that VEGF-induced angiogenesis is also mediated by ROCK, the combination of VEGF and cyclic stretch does not have a synergistic inductive effect on angiogenesis, and is through ROCK-independent pathways. Thus, our findings suggest a change in the molecular control under the presence of both chemical and mechanical pro-angiogenic factors. (2) Cyclic stretch induces preferential alignment of new sprouts, through ROCK-dependent but RTK-independent pathways. Although the RTK inhibitor sunitinib had no effect on stretch-induced alignment, it trended toward suppressing stretch-induced sprout density. Thus, the formation of new sprouts and their directionality may not have completely identical regulatory pathways, and thus it is possible to separately manipulate the number and pattern of new sprouts as needed.

The initial steps for angiogenesis include increased cell proliferation and migration. Taking into account the 3-D nature of our model, proliferation could be observed as either an increase in invasive cells (i.e., by cyclic stretch alone and VEGF alone) or monolayer cell density (i.e., by the combined treatment). We found that, like VEGF-alone stimulation, cyclic stretch alone increased the invasive structure density but did not increase monolayer cell density. Notably, we found that the combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF did not have an additive or synergistic effect on inducing angiogenesis, even though the combination treatment resulted in a significant increase in monolayer cell density when compared to either cyclic stretch or VEGF alone. Although the combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF did not increase the number of invasive structures from the negative control inside the collagen gels, this combination treatment increased the monolayer cell density significantly, suggesting that cyclic stretch and VEGF had an additive effect on cell proliferation in a 2-D but not 3-D setting. The differential effects of the combination treatment on cell densities in 2-D and 3-D settings were unexpected and remain to be explored. It has been shown previously that cyclic biaxial stretch alone can induce proliferation of BAECs when stretched on a 2-D collagen-coated silicone membrane.27 VEGF alone has also been shown to induce proliferation of human microvascular endothelial cells on 2-D collagen-coated plates.6 The combination of cyclic biaxial stretch and VEGF was shown to induce proliferation of rat microvascular endothelial cells when stretched on a 2-D collagen coated membrane.28 These earlier results support the findings in the present study that cyclic uniaxial stretch alone, VEGF alone, or the combination of the two would result in proliferation within our model. With regard to migration, a previous study has shown that cyclic biaxial stretch of BAECs on a 2-D collagen coated membrane can increase BAEC migration.18 VEGF has been shown to increase the migration of bovine retinal endothelial cells.4 The combined effect of cyclic stretch and VEGF on EC migration in 2-D and, particularly, 3-D settings, is currently unknown. However, the present results suggest that cyclic uniaxial stretch alone and VEGF alone, but not the combination of these two factors, may enhance EC migration, and can be explored in the future.

We found that cyclic stretch induces a perpendicular alignment of both monolayer cells and invasive structures, regardless of VEGF treatment. Many 2-D in vitro studies have shown that endothelial cells, either in a confluent monolayer or subconfluent arrangement on a 2-D silicone membrane would align perpendicular to the direction of uniaxial stretch.29–32 Other studies have shown that cyclic uniaxial stretch of a 3-D culture can also orient bovine aortic and human umbilical vein endothelial cells within the underlying/surrounding matrix perpendicular to the direction of stretch.13,15 However, the current study is the first to show and compare how invasive cells (in a 3-D environment) and monolayer cells (in a 2-D environment) respond simultaneously to cyclic uniaxial stretch, both with and without VEGF stimulation. While the scientific questions asked in the present paper and those in the study of Matsumoto et al.15 were similar, there existed several differences between these two studies. Importantly, the 2-D and 3-D experiments in the study by Matsumoto et al. were conducted separately. Their 2-D experiments were performed by seeding endothelial cells on gelatin-coated silicone sheets, and 3-D experiments were performed by embedding endothelial cell-coated dextran beads in fibrin. In contrast, our 3-D stretchable angiogenesis model enables the simultaneous observation of cells on the collagen gel’s surface (in a 2-D environment) and inside the collagen gel (in a 3-D environment). We found that stretch-induced cell alignment occurred in both the 2-D and 3-D environments but at different speeds. Monolayer cells seemed to align better than invasive cells did. Because invasive structures are surrounded by the extracellular matrix (ECM) (specifically, collagen-I in this study), their alignment in response to cyclic stretch may be physically hindered by cell-matrix interactions. This could explain why invasive structures (in a 3-D environment) did not align as well as monolayer cells (in a 2-D environment) during our experimental time frame.

Previous in vitro reports have shown that ECM composition (e.g., collagen vs. fibrin gels) and ECM alignment (i.e., cellular reorganization vs. stretch-induced alignment) can significantly affect angiogenesis and associated vascular patterning. Specifically, the directional sprouting of BAECs from a microcarrier-bead was mediated by the alignment of longer, more organized collagen fibrils but was not mediated by shorter, compact fibrin fibrils.33 Also, rat microvessel fragments cultured in collagen gels were shown to sprout parallel to the direction of collagen fibrils that were aligned parallel to cyclic stretch.34 These results demonstrate the importance of both ECM component alignment and the interplay of both angiogenic sprout and ECM component alignment in response to cyclic stretch. Additionally, ECM stiffness has been shown to significantly affect angiogenesis. In vitro studies have shown that by increasing ECM component concentration (either collagen or fibrin), static angiogenic sprouting is significantly reduced for BAECs and HUVECs.35–38 Collectively, these results underscore the broad range of complex interactive biochemical and mechanical cues that cells must process during sprouting angiogenesis.

We show in this work that ROCK plays a significant role in regulating cyclic stretch-induced sprouting angiogenesis. To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that ROCK inhibition (using 1 μM Y27632) attenuated the increase in cyclic uniaxial stretch-induced sprouting angiogenesis. Cell proliferation and migration, both of which require cellular force,39 are needed for angiogenesis. Y27632 may inhibit angiogenesis via its effects on inhibiting cell proliferation40 and reducing cellular force generation.41 A previous study by static culture has shown that Y27632 (1–100 μM) mitigated the angiogenic activity of HUVECs in a Matrigel tube formation assay.24 Although Y27632 at 0.1–10 μM has been shown to inhibit VEGF-induced sprouting angiogenesis in ex vivo studies (e.g., retinal explants) and in vitro studies (e.g., bovine retinal ECs on collagen gels or human microvascular endothelial cells in fibrin gels),4,8 it is worth noting that studies using both a mouse retinopathy model and HUVECs showed that 0.1 μM H-1152 (another selective ROCK inhibitor42) can enhance VEGF-induced angiogenesis.7

We also show in this work that ROCK inhibition abolished cyclic stretch-induced perpendicular alignment of both monolayer cells and invasive structures. Previous studies have shown that ROCK inhibition significantly limited the perpendicular alignment of BAECs and mouse dermal capillary endothelial cells under uniaxial cyclic stretch at 10% on a 2-D silicone membrane.17,43 The present study, however, is the first to show that ROCK inhibition also limited the perpendicular alignment of invasive cells in a 3-D setting. This inhibition is effective in all stretch treatments, irrespective of the absence or presence of VEGF stimulation.

Regarding temporal considerations in examining the effects of ROCK inhibition on cyclic stretch-mediated angiogenesis and alignment, previous reports have demonstrated the effectiveness of ROCK inhibition (1 – 100 μM Y27632) on in vitro angiogenesis of human microvascular endothelial cells, while having the ROCK inhibitor present throughout 24 hr of experimentation.8,24 In addition, a previous study reported the inhibition of perpendicular cellular alignment induced by cyclic stretch in BAECs via Y27632 (10 μM), while having the inhibitor present also throughout the experimental treatment.17 The present study demonstrates that a 30 min treatment with a 1 μM Y27632 was not sufficiently long enough to result in any significant difference in cyclic stretch-induced angiogenesis and associated cellular alignment. Taken together, results of our study and previous studies highlight the importance of temporal consideration in angiogenesis, particularly in envisioning a dosing and duration protocol for therapeutic options involving ROCK inhibitors. Recently, a clinical study demonstrated a significant reduction in symptoms related to coronary arterial disease by way of a daily 40 mg dose of a specific ROCK inhibitor (Fasudil) administered three times daily in a one-month span.44 The direct comparison between this clinical study and the present study is difficult to ascertain because of the complexity of factors involved in clinical research. However, these preliminary clinical results indicate some promise in using ROCK inhibitors as a therapeutic option in mediating sprouting angiogenesis. Furthermore, some studies have shown that ROCK inhibition by direct means (e.g., ROCK inhibitors) or indirect means (e.g., statins) may be effective in controlling angiogenesis.45–47 The clinical option of using Y27632 to inhibit angiogenesis may be particularly applicable in cardiovascular environments that are routinely subjected to pulsatile blood flow associated cyclic stretch.45,48

Finally, while it is known that VEGF-induced angiogenesis requires ROCK, and herein we demonstrated a need for ROCK signaling in cyclic stretch-mediated angiogenesis, the effect of combination of cyclic stretch and VEGF treatment on the formation of new sprouts was discovered to be independent from ROCK but likely regulated by RTK signaling. Previous studies have shown that cyclic stretch can enhance VEGFR-2 activity in human umbilical vein endothelial cells or rat coronary microvascular endothelial cells stretched on collagen coated 2-D silicone membranes at 20% or 10%, respectively.28,49 Additionally, cyclic stretch of rat coronary microvascular endothelial cells has been shown to increase angiogenic tube length in 3-D culture and migration and proliferation in 2-D culture, and the increase in proliferation and migration were mitigated by a VEGFR inhibitor called Tyrphostn SU-148,28 suggesting the importance of RTK signaling in angiogenesis and angiogenic phases such as migration and proliferation. The results of our inhibitor study are consistent with these 2-D findings and translate them to 3-D culture, as RTK inhibition via sunitinib in our study trended toward reducing density of invasive structures in VEGF-alone treated samples and trended toward suppressing the sprout density induced by stretch alone or a combination of VEGF and stretch stimulation. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the effects of RTK inhibition on cyclic stretch-mediated alignment in both invasive structures and monolayer cells, and we discovered that RTK inhibition did not affect stretch-induced perpendicular alignment. Our results suggest that the formation of sprouts and their directionality do not have completely identical regulatory pathways, and thus it is possible to separately manipulate the number and pattern of new sprouts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the American Heart Association Western States Affiliate (0765113Y) and National Program (0970307N), and the National Institutes of Health (R01HL67646, R01DK088777, R01DK100505).

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Waltenberger J, Claesson-Welsh L, Siegbahn A, Shibuya M, Heldin CH. Different signal transduction properties of KDR and Flt1, two receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26988–26995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmeliet P. VEGF as a key mediator of angiogenesis in cancer. Oncology. 2005;69 (Suppl 3):4–10. doi: 10.1159/000088478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrara N, Davis-Smyth T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:4–25. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryan BA, Dennstedt E, Mitchell DC, Walshe TE, Noma K, Loureiro R, Saint-Geniez M, Campaigniac JP, Liao JK, D’Amore PA. RhoA/ROCK signaling is essential for multiple aspects of VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. FASEB J. 2010;24:3186–3195. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-145102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryan BA, D’Amore PA. What tangled webs they weave: Rho-GTPase control of angiogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2053–2065. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7008-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoang MV, Whelan MC, Senger DR. Rho activity critically and selectively regulates endothelial cell organization during angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1874–1879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308525100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroll J, Epting D, Kern K, Dietz CT, Feng Y, Hammes HP, Wieland T, Augustin HG. Inhibition of Rho-dependent kinases ROCK I/II activates VEGF-driven retinal neovascularization and sprouting angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H893–899. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01038.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Koolwijk P, Versteilen A, van Hinsbergh VW. Involvement of RhoA/Rho kinase signaling in VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:211–217. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000054198.68894.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mac Gabhann F, Qutub AA, Annex BH, Popel AS. Systems biology of pro-angiogenic therapies targeting the VEGF system. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2010;2:694–707. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiu YT, Weiss JA, Hoying JB, Iwamoto MN, Joung IS, Quam CT. The role of mechanical stresses in angiogenesis. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2005;33:431–510. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v33.i5.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown MD. Exercise and coronary vascular remodelling in the healthy heart. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:645–658. doi: 10.1113/eph8802618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egginton S, Zhou AL, Brown MD, Hudlicka O. Unorthodox angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:634–646. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joung IS, Iwamoto MN, Shiu YT, Quam CT. Cyclic strain modulates tubulogenesis of endothelial cells in a 3D tissue culture model. Microvasc Res. 2006;71:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Offenberg Sweeney N, Cummins PM, Cotter EJ, Fitzpatrick PA, Birney YA, Redmond EM, Cahill PA. Cyclic strain-mediated regulation of vascular endothelial cell migration and tube formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto T, Yung YC, Fischbach C, Kong HJ, Nakaoka R, Mooney DJ. Mechanical strain regulates endothelial cell patterning in vitro. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:207–217. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kou B, Zhang J, Singer DR. Effects of cyclic strain on endothelial cell apoptosis and tubulogenesis are dependent on ROS production via NAD(P)H subunit p22phox. Microvasc Res. 2009;77:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaunas R, Nguyen P, Usami S, Chien S. Cooperative effects of Rho and mechanical stretch on stress fiber organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15895–15900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506041102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yano Y, Saito Y, Narumiya S, Sumpio BE. Involvement of rho p21 in cyclic strain-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (pp125FAK), morphological changes and migration of endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:508–515. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu WF, Nelson CM, Tan JL, Chen CS. Cadherins, RhoA, and Rac1 are differentially required for stretch-mediated proliferation in endothelial versus smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2007;101:e44–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birukova AA, Moldobaeva N, Xing J, Birukov KG. Magnitude-dependent effects of cyclic stretch on HGF- and VEGF-induced pulmonary endothelial remodeling and barrier regulation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L612–623. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90236.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkins JR, Pike DB, Gibson CC, Kubota A, Shiu YT. Differential effects of cyclic stretch on bFGF- and VEGF-induced sprouting angiogenesis. Biotechnol Prog. 2014;30:879–888. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uehata M, Ishizaki T, Satoh H, Ono T, Kawahara T, Morishita T, Tamakawa H, Yamagami K, Inui J, Maekawa M, Narumiya S. Calcium sensitization of smooth muscle mediated by a Rho-associated protein kinase in hypertension. Nature. 1997;389:990–994. doi: 10.1038/40187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deeks ED, Keating GM. Sunitinib. Drugs. 2006;66:2255–2266. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666170-00007. discussion 2267–2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uchida S, Watanabe G, Shimada Y, Maeda M, Kawabe A, Mori A, Arii S, Uehata M, Kishimoto T, Oikawa T, Imamura M. The suppression of small GTPase rho signal transduction pathway inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269:633–640. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Bouard S, Herlin P, Christensen JG, Lemoisson E, Gauduchon P, Raymond E, Guillamo JS. Antiangiogenic and anti-invasive effects of sunitinib on experimental human glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2007;9:412–423. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yung YC, Chae J, Buehler MJ, Hunter CP, Mooney DJ. Cyclic tensile strain triggers a sequence of autocrine and paracrine signaling to regulate angiogenic sprouting in human vascular cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15279–15284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905891106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sumpio BE, Banes AJ, Levin LG, Johnson G., Jr Mechanical stress stimulates aortic endothelial cells to proliferate. J Vasc Surg. 1987;6:252–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng W, Christensen LP, Tomanek RJ. Differential effects of cyclic and static stretch on coronary microvascular endothelial cell receptors and vasculogenic/angiogenic responses. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H794–800. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00343.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ives CL, Eskin SG, McIntire LV. Mechanical effects on endothelial cell morphology: in vitro assessment. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1986;22:500–507. doi: 10.1007/BF02621134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iba T, Sumpio BE. Morphological response of human endothelial cells subjected to cyclic strain in vitro. Microvasc Res. 1991;42:245–254. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(91)90059-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dartsch PC, Betz E. Response of cultured endothelial cells to mechanical stimulation. Basic Res Cardiol. 1989;84:268–281. doi: 10.1007/BF01907974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang JH, Goldschmidt-Clermont P, Wille J, Yin FC. Specificity of endothelial cell reorientation in response to cyclic mechanical stretching. J Biomech. 2001;34:1563–1572. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korff T, Augustin HG. Tensional forces in fibrillar extracellular matrices control directional capillary sprouting. J Cell Sci. 1999;112 (Pt 19):3249–3258. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.19.3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krishnan L, Underwood CJ, Maas S, Ellis BJ, Kode TC, Hoying JB, Weiss JA. Effect of mechanical boundary conditions on orientation of angiogenic microvessels. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78:324–332. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghajar CM, Chen X, Harris JW, Suresh V, Hughes CC, Jeon NL, Putnam AJ, George SC. The effect of matrix density on the regulation of 3-D capillary morphogenesis. Biophys J. 2008;94:1930–1941. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.120774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vernon RB, Sage EH. A novel, quantitative model for study of endothelial cell migration and sprout formation within three-dimensional collagen matrices. Microvasc Res. 1999;57:118–133. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1998.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dye J, Lawrence L, Linge C, Leach L, Firth J, Clark P. Distinct patterns of microvascular endothelial cell morphology are determined by extracellular matrix composition. Endothelium. 2004;11:151–167. doi: 10.1080/10623320490512093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kniazeva E, Putnam AJ. Endothelial cell traction and ECM density influence both capillary morphogenesis and maintenance in 3-D. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C179–187. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00018.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shiu YT, Li S, Marganski WA, Usami S, Schwartz MA, Wang YL, Dembo M, Chien S. Rho mediates the shear-enhancement of endothelial cell migration and traction force generation. Biophys J. 2004;86:2558–2565. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin L, Morishige K, Takahashi T, Hashimoto K, Ogata S, Tsutsumi S, Takata K, Ohta T, Kawagoe J, Takahashi K, Kurachi H. Fasudil inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1517–1525. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cascone I, Giraudo E, Caccavari F, Napione L, Bertotti E, Collard JG, Serini G, Bussolino F. Temporal and spatial modulation of Rho GTPases during in vitro formation of capillary vascular network. Adherens junctions and myosin light chain as targets of Rac1 and RhoA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50702–50713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ikenoya M, Hidaka H, Hosoya T, Suzuki M, Yamamoto N, Sasaki Y. Inhibition of rho-kinase-induced myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS) phosphorylation in human neuronal cells by H-1152, a novel and specific Rho-kinase inhibitor. J Neurochem. 2002;81:9–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghosh K, Thodeti CK, Dudley AC, Mammoto A, Klagsbrun M, Ingber DE. Tumor-derived endothelial cells exhibit aberrant Rho-mediated mechanosensing and abnormal angiogenesis in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11305–11310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800835105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nohria A, Grunert ME, Rikitake Y, Noma K, Prsic A, Ganz P, Liao JK, Creager MA. Rho kinase inhibition improves endothelial function in human subjects with coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2006;99:1426–1432. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000251668.39526.c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brandes RP. Statin-mediated inhibition of Rho: only to get more NO? Circ Res. 2005;96:927–929. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000168040.70096.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elewa HF, El-Remessy AB, Somanath PR, Fagan SC. Diverse effects of statins on angiogenesis: new therapeutic avenues. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:169–176. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noma K, Oyama N, Liao JK. Physiological role of ROCKs in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C661–668. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00459.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kozai T, Eto M, Yang Z, Shimokawa H, Luscher TF. Statins prevent pulsatile stretch-induced proliferation of human saphenous vein smooth muscle cells via inhibition of Rho/Rho-kinase pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang H, Wang BW, Kuan P, Shyu KG. Cyclical mechanical stretch enhances angiopoietin-2 and Tie2 receptor expression in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;104:421–428. doi: 10.1042/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]