Abstract

GM3, a major ganglioside of T lymphocytes, promotes human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) entry via interactions with HIV-1 receptors and the viral envelope glycoprotein (Env). Increased GM3 levels in T lymphocytes and the appearance of anti-GM3 antibodies in AIDS patients have been reported earlier. In this study, we investigated the effect of GM3 regulation on HIV-1 entry by utilizing a mouse cell line (B16F10), which expresses exceptionally high levels of GM3. Strikingly, B16 cells bearing CD4, CXCR4, and/or CCR5 were highly resistant to CD4-dependent HIV-1 Env-mediated membrane fusion. In contrast, these targets supported membrane fusion mediated by CD4-requiring HIV-2, SIV, and CD4-independent HIV-1 Envs. Coreceptor function was not impaired by GM3 overexpression as indicated by Ca2+ fluxes mediated by the CXCR4 ligand SDF-1α and the CCR5 ligand MIP-1β. Reduction in GM3 levels of B16 target cells resulted in a significant recovery of CD4-dependent HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion. We propose that GM3 in the plasma membrane blocks HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion by interfering with the lateral association of HIV-1 receptors. Our findings offer a novel mechanism of interplay between membrane lipids and receptors by which host cells may escape viral infections.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) entry is mediated by the interaction of the viral envelope glycoprotein gp120-gp41 (HIV-1 Env) with CD4 and the chemokine receptors in the target cell (4, 26). An involvement of target membrane glycosphingolipids (GSLs) in CD4-mediated HIV-1 entry has been reported earlier (17, 27, 32). Biophysical and immunochemical studies show that the ganglioside GM3 in the plasma membrane of target cells associates with HIV-1 gp120 (14), CD4 (36), and CXCR4 (35) and promotes fusion with HIV-1 Env-expressing cells (17). Our recent studies with GSL-deficient cells suggest that GSLs may promote HIV-1 entry by stabilizing the intermediate steps in the fusion cascade (31). Based on these observations, we hypothesized that overexpression of GSLs (such as Gb3 and GM3), which preferentially partition in the plasma membrane microdomains (34, 40, 42) and have the propensity to interact with HIV-1 Env and their receptors, could have a significant influence on HIV-1 entry.

To test this hypothesis, we examined HIV-1 Env-mediated membrane fusion susceptibility of a mouse melanoma cell line (B16 clone F10) that bears glucosyl ceramide (GlcCer) and GM3 as the only GSLs, among which GM3 is expressed at exceptionally high levels (15). In addition, membrane dynamics of GM3 in B16 cells and its association with other cellular lipid/protein markers has been extensively studied (13). We engineered expression of HIV/SIV receptors in B16F10 cells by using a retroviral vector transduction strategy (31) and monitored membrane fusion with HIV/simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) Env-expressing effector cells by using a fluorescent dye transfer microscopy assay (12). We found that expression of high levels of GM3 in susceptible cells renders them resistant to CD4-dependent HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion. We propose that GM3 acts as a barrier around plasma membrane CD4 preventing subsequent events necessary for the development of a functional fusion pore. Our findings provide a novel mechanism of resistance of host cells to pathogen invasion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Fluorescent probes were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oreg.), and tissue culture media were obtained from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, Calif.). Other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo.). 1-Phenyl-2-hexadecanoylamino-3-morpholino-1-propanol (PPMP) and GSL standards were from Matreya, Inc. (Pleasant Gap, Pa.). Phospholipids were from Avanti-Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, Ala.). Anti-GM3 mouse immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody (GMR6; catalog no. 370695-1) (22) was bought from Seikagaku America (Falmouth, Mass.). vSC50 (6) was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health) from S. Chakrabarti and B. Moss. vPE16 (10), v194 (21), and vCB43 (5) were gifts from P. Earl, C. C. Broder, and B. Moss. CD4-independent HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein plasmids HIV-1IIIB-8X (pSP73-IIIBx) and HIV-1IIIB8X-V3 BaL (pSP73-IIIBx-V3BaL) (16) were kindly provided by Robert W. Doms. B16-F10 cells were from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). The source and culture conditions of GM95, NIH 3T3, and HeLa cells are described elsewhere (31).

HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIV envelope glycoprotein expression.

CD4-requiring envelope proteins were transiently expressed on the surface of HeLa cells by using the recombinant vaccinia virus constructs vPE16 (HIV-1IIIB, X4 utilizing) (10), vSC50 (HIV-2SBL6669, X4 utilizing) (6), vCB43 (HIV-1BaL, R5 utilizing) (5), and v194 (SIVmac251) (21) as described previously (12). For expression of CD4-independent HIV-1 Env, NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with HIV-1IIIB-8X and HIV-1IIIB8X-V3 BaL plasmids as described previously (12).

Stable expression of CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 expression in B16 cells.

B16-F10 cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 4 mM l-glutamine, 1.5 g of sodium bicarbonate/liter, and 4.5 g of glucose (ATCC catalog no. 30-2002)/liter, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Human CD4, WT-human CXCR4, and WT-human CCR5 were stably inserted into B16 cells by using the replication-competent vesicular stomatitis virus-pseudotyped murine leukemia virus-based viruses bearing CXCR4, CCR5, or CD4 essentially as described previously (31). Surface-expressed CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 in B16 cells were determined by using phycoerythrin-conjugated mouse IgG anti-CD4 (RPA-T4), anti-CXCR4 (12G5), or anti-CCR5 (2D7) MAbs as described previously (31).

GSL depletion from B16 cells.

B16 cells were treated with various concentrations of PPMP for 24 to 72 h at 37°C. Total cellular lipids in untreated and PPMP-treated cells were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) as described previously (2). Alternatively, GM3 levels were determined by immunostaining with mouse anti-GM3 IgM antibody (GMR6) as follows. The cells were harvested with enzyme free-cell dissociation buffer. To 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% mouse serum, 2 μg of GMR6 antibody and 2 μg of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse IgM Fab (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, Pa.) were added. This mixture was vortexed and left on ice for 10 min, and subsequently 106 cells were added. Samples were incubated for 1 h on ice, washed twice with PBS-bovine serum albumin (BSA) (2%) buffer and resuspended in PBS-BSA (2%). Samples were resuspended in 1 ml of PBS to be read by a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) at 10,000 events/sample with respect to unlabeled cells. The median intensities from the flow cytometric analysis were deduced and plotted as a function of PPMP concentration. Surface expressed GM3 in NIH 3T3 cells was determined by immunostaining with GMR6 monoclonal antibody (MAb) as described above.

Chemokine-triggered Ca2+ mobilization.

Ca2+ mobilization was measured by incubating cells (107/ml) in loading medium (DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine) with 5 μM Fura-2 A for 30 min at room temperature. The dye-loaded cells were washed and resuspended in saline buffer (138 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 5 mM glucose, 0.1% BSA) or Hanks balanced salt solution at 106/ml. The cells were then transferred into quartz cuvettes (1 × 106 to 2 × 106 cells in 2 ml), which were placed in a luminescence spectrometer (LS-50B; Perkin-Elmer, Beaconsfield, England). Stimulants at different concentrations were added in a volume of 20 μl to each cuvette. The ratio of fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm was calculated by using an FL Win Lab program (Perkin-Elmer).

Fusion assay.

Cell-cell fusion between CD4+ targets and gp120-gp41-expressing effector cells was assayed by using a fluorescent dye transfer method (29). We used the fluorescent dyes CMTMR, [(5-(and-6) (((4chloromethyl)benzoyl)amino)tetramethylrhodamine; green emission, excitation/emission (ex/em) 540/566 nm]; CMFDA (5-cholormethyl fluorescein diacetate; blue emission, ex/em 492/516 nm); or calcein (blue emission, ex/em 496/517 nm) to label the cells for fusion assay.

Typically, target cells were plated on 12-well clusters at a density of 50,000 cells/well 1 day prior to fusion experiments and were labeled with 10 μM CMTMR for 1 h at 37°C. Envelope-expressing cells were labeled with CMFDA (10 μM) or Calcein-AM (0.5-1 μM) for 1 to 2 h at 37°C according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fluorescence-labeled effector and target cells were cocultured under various experimental conditions. Details of the culture conditions relevant to each particular experiment are given in the figure legends. Dye redistribution was monitored microscopically as described previously (28). The extent of fusion was calculated as follows: percent fusion = 100 × the number of bound cells positive for both dyes/the number of bound cells positive for target cells.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

B16 cells bearing HIV-1 receptors are resistant to CD4-dependent HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion.

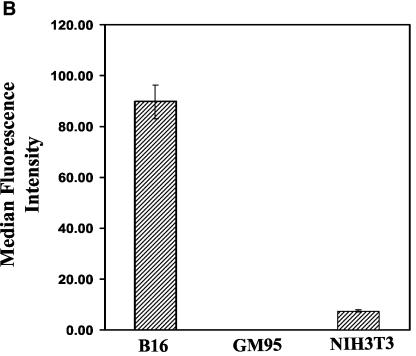

To examine the effect of elevated expression of GM3 on HIV-1 fusion, we used a mouse melanoma cell line (B16F10) (15) that expresses at least 10-fold-higher levels of GM3 than NIH 3T3 cells (see Fig. 2B). We engineered expression of CD4, CXCR4, and/or CCR5 in B16 cells by using a similar procedure as previously described for GM95 (31) and tested their fusion capability. HIV-1IIIB and HIV-2SBL/ISY Env-expressing cells (fluorescently labeled with an aqueous probe, calcein) were incubated with B16CD4CXCR4 cells (fluorescently labeled with the cytoplasmic dye CMTMR) for 2 to 8 h at 37°C and fusion was monitored by the overlap of calcein and CMTMR in fused cells by microscopy of cocultured Env/target cell pairs (Fig. 1). Phase-contrast images of cocultured effector/target cell pairs are shown (Fig. 1a and c) with the corresponding red-green overlays (Fig. 1b and d). B16CD4CXCR4 cells did not show any significant fusion when incubated with HIV-1 Env-expressing cells (Fig. 1a and b). On the other hand, incubation of B16CD4CXCR4 cells with HIV-2 Env-expressing cells under similar conditions resulted in massive fusion evident by the appearance of yellow color in the overlays and formation of multinucleated cells (syncytia) (Fig. 1d). These results confirmed that CD4 and CXCR4 could be utilized in these cells and that the B16 cell membrane was not defective in supporting fusion. Similarly, we observed very little or no fusion when B16CD4CCR5 cells were cultured with HIV-1 BaL-expressing cells, whereas these cells supported SIV-Env-mediated fusion (Table 1). Prolonged cocultures (up to 16 h at 37°C) did not result in increased HIV-1 fusion, suggesting that blockade of HIV-1 fusion in these cells was not due to delayed kinetics or to low receptor levels (data not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate that B16CD4CXCR4 and B16CD4CCR5 cells are highly resistant to HIV-1 Env but not HIV-2/SIV Env-mediated membrane fusion.

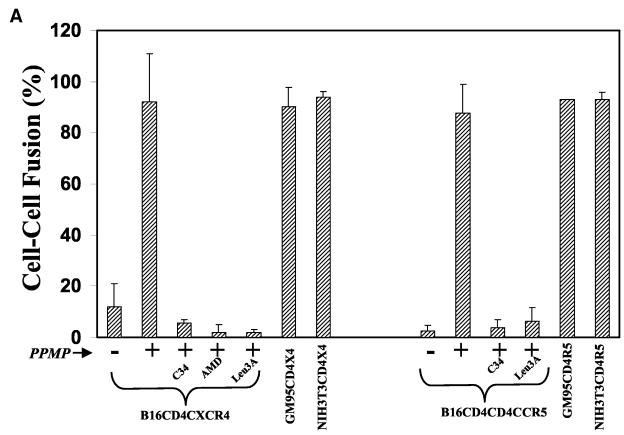

FIG. 2.

GSL Depletion from B16 bearing HIV-1 receptor cells restores HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion. (A) Target cells were treated with 10 μM PPMP for 60 to 72 h at 37°C, plated on 12-well clusters (50,000 per well), and labeled with CMTMR. CMTMR-labeled target cells were incubated with the corresponding calcein-labeled HIV-1 Env-expressing HeLa cells for 4 to 6 h at 37°C in the absence or presence of various inhibitors as indicated. Fusion was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. The values represent an average (± the standard deviation) from three to five samples within a single experiment. The results were reproducible from at least three independent experiments. (B) Cell surface-expressed GM3 in B16 cells was determined by immunostaining with anti-GM3 MAb (GMR6) as described in Materials and Methods. The results are presented as median fluorescence intensities from three individual measurements. Similar results were obtained from at least three independent experiments.

FIG. 1.

B16 cells bearing HIV-1 receptors are resistant to HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion. CD4-requiring envelope proteins were transiently expressed on the surface of HeLa cells by using the recombinant vaccinia virus constructs vPE16 (HIV-1IIIB, X4 utilizing) and vSC50 (HIV-2SBL6669, X4 utilizing). CMTMR-labeled B16CD4CXCR4 cells (on 12-well clusters) were cocultured with calcein-labeled envelope-expressing cells for 2 to 4 h at 37°C. Fusion was monitored by using the fluorescent dye transfer and by formation of multinucleated cells (syncytia) upon fusion (see Materials and Methods). Phase images are shown for HIV-1IIIB (a) and HIV-2SBL/ISY (c) fusion, respectively. Red-green overlays of the cell pairs are shown in panels b (HIV-1IIIB) and d (HIV-2SBL/ISY).

TABLE 1.

Viral proteins and receptors examined in this study

| Receptor(s) | Viral envelopea | Fusion efficiencyb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| B16 cells | NIH 3T3 cells | ||

| CD4/CXCR4 | HIV-1 IIIB (BH8) | +/− | +++++ |

| IIIB-8x | ++++ | ++++ | |

| HIV-2 (SBL/ISY) | +++ | +++++ | |

| CXCR4 | HIV-1 IIIB (BH8) | − | − |

| IIIB-8x | +++ | +++ | |

| HIV-2 (SBL/ISY) | − | − | |

| CD4/CCR5 | HIV-1 BaL | +/− | +++++ |

| IIIB-8x-V3BaL | ++++ | ++++ | |

| SIV | +++ | +++++ | |

| CCR5 | HIV-1 BaL | − | − |

| IIIB-8x-V3BaL | +++ | +++ | |

HeLa cells were infected with the recombinant vaccinia virus constructs vPE16, vSC50, vCB43, and v194 as described previously (12). For expression of CD4-independent HIV-1 Env, NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with IIIB-8x and IIIB-8x-V3 BaL plasmids.

Fusion between CD4+ targets and Env-expressing effector cells was monitored as described in Materials and Methods. Fusion efficiency is indicated as follows: +++++ (100%), +++ (>50%), and +/− (<10%).

Blockade of HIV-1 fusion in B16 cell lines is not due to inefficient coreceptor interactions.

To determine the mechanism(s) of blockade of HIV-1 fusion in B16 cell lines, we used mutant HIV-1 envelopes (8X or 8XV3BaL), which do not require cellular CD4 to support fusion. When B16CD4CXCR4 (or B16CXCR4) were cultured with 8X-Env-expressing NIH 3T3 cells at 37°C, fusion occurred with an efficiency similar to that of NIH 3T3 cell lines. A comparison of efficiency of HIV-1, HIV-2 or SIV-Env-mediated fusion with NIH 3T3 or B16 cells bearing HIV/SIV receptors is presented in Table 1. These data indicate that the block in fusion of B16CD4CXCR4 or B16CD4CCR5 cells by CD4-requiring HIV-1 envelope was not due to its inability to interact with chemokine receptors. We surmise that the fusion of B16CD4CXCR4/HIV-2 Env- and B16CD4CCR5/SIV Env-expressing cell pairs is due to a relatively lower CD4 requirement (3, 20) and that, in the B16 cells, there appears to be sufficient “free” CD4 available to trigger HIV-2, SIV but not HIV-1 fusion.

Reduction in GM3 levels in B16 cells restores fusion with HIV-1 Env-expressing cells.

The results presented in Fig. 1 and Table 1 suggest that the block in CD4-dependent HIV-1 fusion might result from a weak and/or insufficient CD4/HIV-1 Env interaction. Plasma membrane GM3 has been shown to associate with cellular CD4 in human peripheral blood lymphocytes (36). Rapid downmodulation of CD4 by exogenously added GM3 in CD4+ lymphocytes has also been reported earlier (38). Therefore, we predicted that GM3 may act as a blocker for cellular CD4 prohibiting efficient interactions with HIV-1 Env and/or coreceptor. If the inability of B16 cells to support HIV-1 fusion was predominantly due to the CD4 engagement by GM3, then a decrease in GM3 levels should restore fusion. The experiments described below show that this indeed was the case.

To reduce GM3 levels in B16 cells, we used PPMP, a glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor, which acts on an early step in the GSL biosynthesis pathway (1). B16 cells were treated with 10 μM PPMP for 48 to 72 h at 37°C. When PPMP-treated B16CD4CXCR4 cells were incubated with HIV-1IIIB-expressing HeLa cells, massive fusion occurred within 2 to 4 h at 37°C (Fig. 2, 92% ± 18% fusion). In contrast, untreated cells did not support efficient fusion (Fig. 2, 9% ± 5% fusion). HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion with PPMP-treated B16 cells was inhibited in the presence of reagents, which are known to block the CD4-gp120 interaction (Leu3A MAb) (23), compete for the CXCR4 binding site (AMD3100) (9), or interfere with the envelope transmembrane six helix bundle formation (peptide C34) (7), confirming that fusion was mediated through HIV-1 gp120-gp41 (Fig. 2). Fusion activity of receptor bearing mutant GM95 cells which were derived from B16 cells by chemical mutagenesis and selection with antibodies against melanoma antigen (18) and NIH 3T3 cells (which express physiological levels of GSLs) is also shown for comparison (Fig. 2). Untreated GM95CD4CXCR4 and NIH3T3CD4CXCR4 cells readily fused with HIV-1IIIB Env-expressing cells under identical culture conditions as previously reported (Fig. 2). Pretreatment of GSL-deficient GM95CD4CXCR4 cells with PPMP did not modulate fusion efficiency, whereas fusion of NIH3T3CD4CXCR4 cells was reduced as previously reported (31). PPMP treatment of B16CD4CCR5 cells also resulted in a marked increase in fusion mediated by HIV-1BaL Env (Fig. 2A). Leu3A and C34 blocked fusion, confirming that fusion was mediated by HIV-1 envelope. Fusion activity of GM95CD4CCR5 and NIH3T3CD4CCR5 cells is also shown in Fig. 2A. To compare the relative expression of surface-expressed GM3 in B16 cells with the fusion-competent GSL+ NIH 3T3 cells, we performed immunostaining with an anti-GM3 MAb (GMR6) as described in Materials and Methods. The average median intensities of surface-expressed GM3 in B16 and NIH 3T3 cells are shown in Fig. 2B. We did not observe any GM3 expression in GSL-deficient GM95 cells, as expected. The results presented in Fig. 2B clearly demonstrate that B16 cells express at least 10-fold-higher levels of GM3.

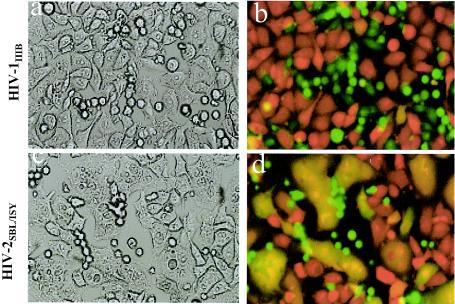

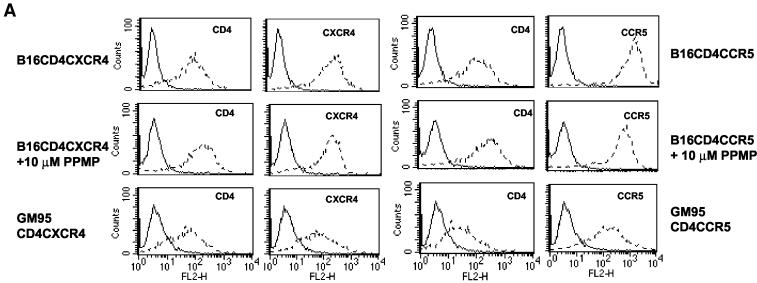

Effect of PPMP treatment on receptor(s) expression of B16 cells.

Our previous studies show that PPMP treatment of CD4+ cell lines had no effect on CD4, CXCR4 levels or chemokine receptor-triggered chemotaxis. However, a reduction in CCR5 expression was observed after PPMP treatment (17). Since B16 cells bearing HIV-1 receptors were poorly susceptible to fusion, we examined whether the fusion enhancement in PPMP-treated cells was due to receptor(s) upregulation by as-yet-unidentified mechanisms. The cells (pretreated with 10 μM PPMP) were incubated with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD4, CXCR4, or CCR5 antibodies and surface immunofluorescence was detected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Fig. 3A). The CD4, CXCR4, or CCR5 expression levels in B16 cells were similar to that of the fusion competent GSL-deficient mutant GM95 cells (Fig. 3A). We observed a slight increase in surface-expressed CD4 (Fig. 3A) in B16CD4CXCR4 and B16CD4CCR5 cells upon treatment with PPMP. However, fusion recovery in B16 cells cannot alone be attributed to this slight increase in CD4 levels, because GM95 cells expressing similar (GM95CD4CXCR4) or even slightly lower (GM95CD4CCR5) levels of CD4 readily fused with HIV-1 Env-expressing cells (Fig. 2).

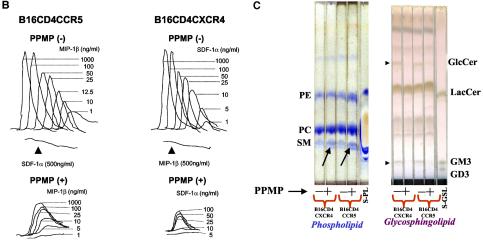

FIG. 3.

Effect of PPMP treatment on cellular lipids, receptor(s) expression and chemokine receptor-triggered Ca2+ fluxes of B16 cells bearing HIV-1 receptors. Target cells were treated with 10 μM PPMP for 60 to 72 h at 37°C. The cells were stained with antibodies (A), analyzed for chemokine-induced Ca2+ flux (B), or subjected to total lipid extraction (2) (C). (A) Surface expression of receptors before and after treatment with PPMP was determined by staining with phycoerythrin-conjugated RPA-T4 (CD4), 12G5 (CXCR4), or 2D7 (CCR5) MAb and the corresponding isotype controls, and fluorescence was examined with a Becton Dickinson FACScalibur (31). GM95 cell lines expressing CD4 and CXCR4 or CCR5 were used for comparison. Solid lines, isotype controls; dotted lines, CD4, CXCR4, or CCR5 as indicated in the figure. (B) Chemokine-triggered Ca2+ mobilization was examined by measuring the ratio of fluorescence of Fura-2-loaded cells at 340 and 380 nm at different concentrations of stimulants essentially as described in Materials and Methods. (C) The lipids were analyzed by TLC with CHCl3-MeOH-H2O (65:25:04). GSLs and phospholipids were identified by using Orcinol and molybdenum blue spray, respectively (2). A lipid profile of B16CD4CXCR4 and B16CD4CCR5 cells before and after treatment with PPMP is shown in Fig. 3C. Phospholipid standards (S-PL) include phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and sphingomyelin (SM). GSL standards (S-GSL) include LacCer (lactosyl ceramide), GM3, and GD3 as indicated. GlcCer that is expressed in B16 cells besides GM3 is also indicated in the figure (right panel). An increase of sphingomyelin in PPMP-treated cells is indicated by arrow in the phospholipid-stained TLC plate (Fig. 3C, left panel).

To further characterize the properties of chemokine receptors expressed on B16 cells, we determined Ca2+ mobilization of the cells in response to SDF-1α and MIP-1β (Fig. 3B). We observed robust chemokine-induced Ca2+ fluxes (Fig. 3B, top panels) in B16CD4CXCR4 and CCR5 cells, which, nonetheless, only showed very poor fusion efficiency with HIV-1 Env-expressing cells (Fig. 1 and 2 and Table 1). Although PPMP treatment of B16 cells resulted in a decrease in Ca2+ flux in the presence of chemokines (Fig. 3B, lower panels), these cells showed a remarkable increase in fusion when incubated with HIV-1 Env-expressing cells (Fig. 2). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the poor capacity of HIV-1 fusion of B16 cells was not due to altered expression and/or conformation of chemokine receptors on these cells

Effect of PPMP treatment on lipid profile of B16 cells.

To assess the effect of PPMP treatment on overall lipid profile, we isolated total cell lipids and analyzed phospholipid and sphingolipid profile (2). The TLC findings of lipids extracted from B16CD4CXCR4 and B16CD4CCR5 cells are shown in Fig. 3C. GSLs were identified by staining with Orcinol spray (2), which reacts with carbohydrate moieties of GSLs producing a distinct purple color (Fig. 3C, right panel). The relative mobility values of various lipids were identified by comparing the known phospholipid and GSL standards. It is evident from the TLC that PPMP treatment resulted in a significant decrease in GlcCer and GM3 levels (indicated by arrows), the only GSLs expressed in B16 cells. Interestingly, B16 cells displayed a clear upregulation in sphingomyelin (Fig. 3C, left panel, arrows). A reduction in surface-expressed GM3 in PPMP treated B16 cells was further confirmed by immunostaining with a mouse IgM MAb (GMR6), which binds to GM3 (22) (Fig. 4B).

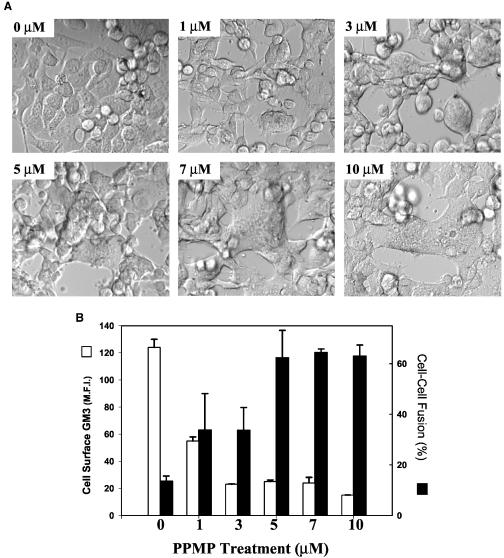

FIG. 4.

The block of HIV-1 fusion with B16 targets is dependent on the levels of GM3. B16CDCXCR4 cells (25,000 per well on a 12-well plate) were treated with various concentrations of PPMP for 24 h at 37°C and labeled with CMTMR. The cells were cultured with CMFDA-labeled HIV-1IIIB-expressing cells as described in legend to Fig. 1. Panel A shows phase-contrast images (using a ×20 lens) showing recovery of HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion determined by the syncytium formation as a function of increased dose of PPMP (0 to 10 μM) pretreatment. Positive fusion was confirmed by CMTMR/CMFDA overlays (not shown). The percent fusion was calculated as described in Materials and Methods, and the data are presented in panel B (solid bars). The PPMP-treated target cells were also analyzed for surface-expressed GM3 by immunostaining with GMR6 mouse MAb (see Materials and Methods) in the same experiment. The average median fluorescence intensity is expressed as a function of various PPMP treatments (panel B, open bars). The values represent an average (± the standard deviation) from three to five samples with in a single experiment. The results were reproducible from at least three independent experiments.

Recovery of HIV-1 fusion in B16 cells correlates with decrease in surface-expressed GM3.

Our results presented above indicate that high levels of expression of GM3 in B16 cells is the likely cause for their resistance to fusion with HIV-1 Env-expressing cells. If this were the case, the increase in fusion efficiency would correlate with the reduction of GM3 from the cell surface. To examine this, we treated B16 cells at various doses of PPMP for 24 and 48 h at 37°C. When PPMP-treated B16 cells were cultured with HIV-1 Env-expressing cells for 2 to 4 h at 37°C, we observed an enhancement in fusion as a function of increased doses of PPMP pretreatment. Figure 4 shows the results obtained with B16CD4CXCR4 cells preincubated with various doses of PPMP for 24 h at 37°C. It is clear from the data presented in Fig. 4 that the recovery of HIV-1 fusion was enhanced after pretreatment with increased concentrations of PPMP (Fig. 4A and B). Pretreatment with PPMP at concentrations of >5 μM resulted in massive syncytium formation (Fig. 4A). Treatment with lower doses of the drug (1 and 3 μM) partially recovered fusion, whereas untreated cells showed very low fusion efficiency. Quantitative analysis of fusion by using the dye transfer method confirmed that pretreatment of B16 cells at >5 μM for 24 h at 37°C resulted in maximum recovery of fusion (Fig. 4B, solid bars). Determination of surface expressed GM3 by immunostaining with the anti-GM3 GMR6 MAb revealed that the treatment with 1 μM PPMP resulted in ca. 60% decrease in GM3 levels (Fig. 4B, open bars), whereas fusion was only partially recovered (30%, Fig. 4B). At least a 10-fold decrease in GM3 levels was observed after pretreatment with 3 to 10 μM PPMP, which correlated with the maximum recovery of fusion (60 to 70%). The results presented in Fig. 4 confirm that elevated GM3 expression in B16 cells bearing HIV-1 receptors primarily contributes to the resistance to HIV-1 fusion. Since the extent of recovery of HIV-1 fusion correlated with the decrease in surface-expressed GM3 levels in B16 cell lines, we propose that GM3 acts as a barrier around plasma membrane CD4, thereby preventing subsequent interactions necessary for the development of a functional fusion pore.

In the present study we have demonstrated that mouse melanoma B16 cells bearing HIV/SIV receptors are highly resistant to CD4-mediated HIV-1 fusion. The resistance to HIV-1 fusion occurs independently of coreceptor usage by the viral envelope. Nevertheless, overexpression of GM3 in these cells did not impair fusion mediated by HIV-2 and SIV Env. Since the GSL dependence, temperature, cytoskeleton, and receptor affinities (8, 19, 24) are different in HIV-2 Env-mediated fusion, HIV-1 may have different membrane structural and dynamic requirements for entry into cells. Interestingly, CD4-independent mutant HIV-1 envelopes fused with B16 targets, suggesting that the lack of fusion with CD4-dependent HIV-1 envelopes was at the level of CD4/HIV-1 Env protein interactions. Treatment of B16 cells bearing HIV-1 receptors with a GSL biosynthesis inhibitor, PPMP, restored fusion with X4-dependent HIV-1 envelopes, as well as with R5-utilizing CD4-dependent HIV-1 envelopes, suggesting a role of GM3 in modulating HIV-1 fusion reaction.

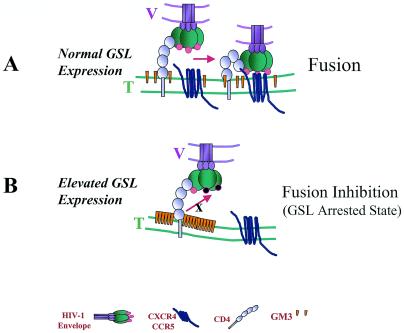

GM3, a raft-associated GSL (34, 37), is known to associate with HIV-1 receptors in cultured cell lines and primary lymphocytes (35, 36, 38). We propose that exceptionally high levels of GM3 engage HIV-1 gp120-gp41/CD4 complex (GM3 arrested state, Fig. 5) in specialized regions (presumably rafts) in the plane of B16 membrane. We had previously shown that inhibition of GSL biosynthesis in various cell lines by treatment with PPMP reduced their susceptibility to CD4-dependent HIV-1 fusion and infection and that this defect can be restored by adding back GM3 (17, 30). However, the present study shows that the presence of highly elevated levels of GM3 on the cell surface inhibits HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion. Thus, it seems that GM3 affects HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion in different ways depending on cell surface levels of GM3 and HIV-1 receptors. These effects may be reconciled by considering the two-step model for HIV-1 Env-receptor engagement (11) that involves initial interactions between gp120 and CD4, followed by conformational changes that permit the formation of the trimolecular complex of gp120-CD4-coreceptor (see Fig. 5). The probability of coreceptor engagement is enhanced by localization of CD4 clusters at a reasonable distance from coreceptor clusters (33, 39, 41). We hypothesize that at relatively normal concentrations cell surface GM3 facilitates the formation of a tetramolecular complex of gp120-CD4-coreceptor-GM3 that leads to a more robust engagement of coreceptor (Fig. 5A) and subsequent fusion. However, highly elevated levels of GM3 may engage CD4, thereby reducing the probability of gp120-CD4-coreceptor complex formation and fusion (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Model depicting a “GM3 arrested state” in B16 cells bearing HIV receptors. In this model, we predict that overexpression of GM3 arrests CD4 by in situ lateral interactions. V, viral membrane; T, target membrane. (A) At physiological GM3 expression, HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein interacts with CD4 resulting in conformational changes indicated by circles (pink). This leads to the subsequent interactions with the chemokine receptor, which leads to fusion between viral and target membrane. (B) In contrast, in B16 cells overexpression of GM3 (indicated by orange cones) inhibits activation of HIV-1 Env (indicated by black circles) and/or prevents subsequent interaction with the chemokine receptor.

GM3-mediated regulation of receptors required for HIV-1 entry is not unique. For instance, GM3-mediated modulation of epidermal growth factor (25) and of insulin (43) receptor function have been reported. It remains to be explored whether altered GSL metabolism is a way for the cells to escape susceptibility to HIV-1 infection and whether GSL expression can be targeted for antiviral therapies.

Acknowledgments

vSC50 was obtained through the AIDS reagent and Reference Program (NIAID, NIH) from S. Chakarbati and B. Moss. We thank Cathy M. Larrain for assistance in fusion assays. We thank members of the Blumenthal lab for their sustained support during this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe, A., J. Inokuchi, M. Jimbo, H. Shimeno, A. Nagamatsu, J. A. Shayman, G. S. Shukla, and N. S. Radin. 1992. Improved inhibitors of glucosylceramide synthase. J. Biochem. 111:191-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ablan, S., S. S. Rawat, R. Blumenthal, and A. Puri. 2001. Entry of influenza virus into a glycosphingolipid-deficient mouse skin fibroblast cell line. Arch. Virol. 146:2227-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bannert, N., D. Schenten, S. Craig, and J. Sodroski. 2000. The level of CD4 expression limits infection of primary rhesus monkey macrophages by a T-tropic simian immunodeficiency virus and macrophagetropic human immunodeficiency viruses. J. Virol. 74:10984-10993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger, E. A. 1997. HIV entry and tropism: the chemokine receptor connection. AIDS 11(Suppl. A):S3-S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broder, C. C., and E. A. Berger. 1995. Fusogenic selectivity of the envelope glycoprotein is a major determinant of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tropism for CD4+ T-cell lines versus primary macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:9004-9008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakrabarti, S., T. Mizukami, G. Franchini, and B. Moss. 1990. Synthesis, oligomerization, and biological activity of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 envelope glycoprotein expressed by a recombinant vaccinia virus. Virology 178:134-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, D. C., D. Fass, J. M. Berger, and P. S. Kim. 1997. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell 89:263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clapham, P. R., D. Blanc, and R. A. Weiss. 1991. Specific cell surface requirements for the infection of CD4-positive cells by human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 and by simian immunodeficiency virus. Virology 181:703-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donzella, G. A., D. Schols, S. W. Lin, J. A. Este, K. A. Nagashima, P. J. Maddon, G. P. Allaway, T. P. Sakmar, G. Henson, E. de Clercq, and J. P. Moore. 1998. AMD3100, a small molecule inhibitor of HIV-1 entry via the CXCR4 coreceptor. Nat. Med. 4:72-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Earl, P. L., S. Koenig, and B. Moss. 1991. Biological and immunological properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein: analysis of proteins with truncations and deletions expressed by recombinant vaccinia viruses. J. Virol. 65:31-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallo, S. A., C. M. Finnegan, M. Viard, Y. Raviv, A. Dimitrov, S. S. Rawat, A. Puri, S. Durell, and R. Blumenthal. 2003. The HIV Env-mediated fusion reaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1614:36-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallo, S. A., A. Puri, and R. Blumenthal. 2001. HIV-1 gp41 six-helix bundle formation occurs rapidly after the engagement of gp120 by CXCR4 in the HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion process. Biochemistry 40:12231-12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakomori, S. 1998. New insights in glycosphingolipid function: “glycosignaling domain,” a cell surface assembly of glycosphingolipids with signal transducer molecules, involved in cell adhesion coupled with signaling. Glycobiology 8:xi-xix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammache, D., G. Pieroni, N. Yahi, O. Delezay, N. Koch, H. Lafont, C. Tamalet, and J. Fantini. 1998. Specific interaction of HIV-1 and HIV-2 surface envelope glycoproteins with monolayers of galactosylceramide and ganglioside GM3. J. Biol. Chem. 273:7967-7971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirabayashi, Y., A. Hamaoka, M. Matsumoto, T. Matsubara, M. Tagawa, S. Wakabayashi, and M. Taniguchi. 1985. Syngeneic monoclonal antibody against melanoma antigen with interspecies cross-reactivity recognizes GM3, a prominent ganglioside of B16 melanoma. J. Biol. Chem. 260:13328-13333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman, T. L., C. C. LaBranche, W. Zhang, G. Canziani, J. Robinson, I. Chaiken, J. A. Hoxie, and R. W. Doms. 1999. Stable exposure of the coreceptor-binding site in a CD4-independent HIV-1 envelope protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:6359-6364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hug, P., H. M. Lin, T. Korte, X. Xiao, D. S. Dimitrov, J. M. Wang, A. Puri, and R. Blumenthal. 2000. Glycosphingolipids promote entry of a broad range of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates into cell lines expressing CD4, CXCR4, and/or CCR5. J. Virol. 74:6377-6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichikawa, S., N. Nakajo, H. Sakiyama, and Y. Hirabayashi. 1994. A mouse B16 melanoma mutant deficient in glycolipids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2703-2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jernigan, K. M., R. Blumenthal, and A. Puri. 2000. Varying effects of temperature, Ca2+ and cytochalasin on fusion activity mediated by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and type 2 glycoproteins. FEBS Lett. 474:246-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabat, D., S. L. Kozak, K. Wehrly, and B. Chesebro. 1994. Differences in CD4 dependence for infectivity of laboratory-adapted and primary patient isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 68:2570-2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koenig, S., V. M. Hirsch, R. A. Olmsted, D. Powell, W. Maury, A. Rabson, A. S. Fauci, R. H. Purcell, and P. R. Johnson. 1989. Selective infection of human CD4+ cells by simian immunodeficiency virus: productive infection associated with envelope glycoprotein-induced fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:2443-2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotani, M., H. Ozawa, I. Kawashima, S. Ando, and T. Tai. 1992. Generation of one set of monoclonal antibodies specific for a-pathway ganglio-series gangliosides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1117:97-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu, S., S. D. Putney, and H. L. Robinson. 1992. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry into T cells: more-rapid escape from an anti-V3 loop than from an antireceptor antibody. J. Virol. 66:2547-2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKnight, A., M. T. Dittmar, J. Moniz-Periera, K. Ariyoshi, J. D. Reeves, S. Hibbitts, D. Whitby, E. Aarons, A. E. Proudfoot, H. Whittle, and P. R. Clapham. 1998. A broad range of chemokine receptors are used by primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 as coreceptors with CD4. J. Virol. 72:4065-4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meuillet, E. J., B. Mania-Farnell, D. George, J. I. Inokuchi, and E. G. Bremer. 2000. Modulation of EGF receptor activity by changes in the GM3 content in a human epidermoid carcinoma cell line, A431. Exp. Cell Res. 256:74-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore, J. P., B. A. Jameson, R. A. Weiss, and Q. J. Sattentau. 1993. The HIV-cell fusion reaction, p. 233-289. In J. Bentz (ed.), Viral fusion mechanisms. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 27.Puri, A., P. Hug, K. Jernigan, J. Barchi, H. Y. Kim, J. Hamilton, J. Wiels, G. J. Murray, R. O. Brady, and R. Blumenthal. 1998. The neutral glycosphingolipid globotriaosylceramide promotes fusion mediated by a CD4-dependent CXCR4-utilizing HIV type 1 envelope glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14435-14440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puri, A., P. Hug, I. Munoz-Barroso, and R. Blumenthal. 1998. Human erythrocyte glycolipids promote HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein-mediated fusion of CD4+ cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 242:219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puri, A., M. Paternostre, and R. Blumenthal. 2002. Lipids in viral fusion. Methods Mol. Biol. 199:61-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puri, A., S. S. Rawat, H. M. Lin, C. M. Finnegan, J. Mikovits, F. W. Ruscetti, and R. Blumenthal. 2004. An inhibitor of glycosphingolipid metabolism blocks HIV-1 infection of primary T cells. AIDS 18:849-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rawat, S. S., J. Eaton, S. A. Gallo, T. D. Martin, S. Ablan, S. Ratnayake, M. Viard, V. N. KewalRamani, J. M. Wang, R. Blumenthal, and A. Puri. 2004. Functional expression of CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 in glycosphingolipid-deficient mouse melanoma GM95 cells and susceptibility to HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein-triggered membrane fusion. Virology 318:55-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rawat, S. S., M. Viard, S. A. Gallo, A. Rein, R. Blumenthal, and A. Puri. 2003. Modulation of entry of enveloped viruses by cholesterol and sphingolipids. Mol. Membr. Biol. 20:243-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singer, I. I., S. Scott, D. W. Kawka, J. Chin, B. L. Daugherty, J. A. De-Martino, J. DiSalvo, S. L. Gould, J. E. Lineberger, L. Malkowitz, M. D. Miller, L. Mitnaul, S. J. Siciliano, M. J. Staruch, H. R. Williams, H. J. Zweerink, and M. S. Springer. 2001. CCR5, CXCR4, and CD4 are clustered and closely apposed on microvilli of human macrophages and T cells. J. Virol. 75:3779-3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sorice, M., T. Garofalo, R. Misasi, V. Dolo, G. Lucania, T. Sansolini, I. Parolini, M. Sargiacomo, M. R. Torrisi, and A. Pavan. 1999. Glycosphingolipid domains on cell plasma membrane. Biosci. Rep. 19:197-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorice, M., T. Garofalo, R. Misasi, A. Longo, V. Mattei, P. Sale, V. Dolo, R. Gradini, and A. Pavan. 2001. Evidence for cell surface association between CXCR4 and ganglioside GM3 after gp120 binding in SupT1 lymphoblastoid cells. FEBS Lett. 506:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorice, M., T. Garofalo, R. Misasi, A. Longo, J. Mikulak, V. Dolo, G. M. Pontieri, and A. Pavan. 2000. Association between GM3 and CD4-Ick complex in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Glycoconj. J. 17:247-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorice, M., I. Parolini, T. Sansolini, T. Garofalo, V. Dolo, M. Sargiacomo, T. Tai, C. Peschle, M. R. Torrisi, and A. Pavan. 1997. Evidence for the existence of ganglioside-enriched plasma membrane domains in human peripheral lymphocytes. J. Lipid Res. 38:969-980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sorice, M., A. Pavan, R. Misasi, T. Sansolini, T. Garofalo, L. Lenti, G. M. Pontieri, L. Frati, and M. R. Torrisi. 1995. Monosialoganglioside GM3 induces CD4 internalization in human peripheral blood T lymphocytes. Scand. J. Immunol. 41:148-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steffens, C. M., and T. J. Hope. 2003. Localization of CD4 and CCR5 in living cells. J. Virol. 77:4985-4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taga, S., K. Carlier, Z. Mishal, C. Capoulade, M. Mangeney, Y. Lecluse, D. Coulaud, C. Tetaud, L. L. Pritchard, T. Tursz, and J. Wiels. 1997. Intracellular signaling events in CD77-mediated apoptosis of Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Blood 90:2757-2767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viard, M., I. Parolini, M. Sargiacomo, K. Fecchi, C. Ramoni, S. Ablan, F. W. Ruscetti, J. M. Wang, and R. Blumenthal. 2002. Role of cholesterol in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein-mediated fusion with host cells. J. Virol. 76:11584-11595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiels, J. 2000. CD77. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 14:288-289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamashita, T., A. Hashiramoto, M. Haluzik, H. Mizukami, S. Beck, A. Norton, M. Kono, S. Tsuji, J. L. Daniotti, N. Werth, R. Sandhoff, K. Sandhoff, and R. L. Proia. 2003. Enhanced insulin sensitivity in mice lacking ganglioside GM3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:3445-3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]