Abstract

ZEBRA, a member of the bZIP family, serves as a master switch between latent and lytic cycle Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) gene expression. ZEBRA influences the activity of another viral transactivator, Rta, in a gene-specific manner. Some early lytic cycle genes, such as BMRF1, are activated in synergy by ZEBRA and Rta. However, ZEBRA suppresses Rta's ability to activate a late gene, BLRF2. Here we show that this repressive activity is dependent on the phosphorylation state of ZEBRA. We find that two residues of ZEBRA, S167 and S173, that are phosphorylated by casein kinase 2 (CK2) in vitro are also phosphorylated in vivo. Inhibition of ZEBRA phosphorylation at the CK2 substrate motif, either by serine-to-alanine substitutions or by use of a specific inhibitor of CK2, abolished ZEBRA's capacity to repress Rta activation of the BLRF2 gene, but did not alter its ability to initiate the lytic cycle or to synergize with Rta in activation of the BMRF1 early-lytic-cycle gene. These studies illustrate how the phosphorylation state of a transcriptional activator can modulate its behavior as an activator or repressor of gene expression. Phosphorylation of ZEBRA at its CK2 sites is likely to play an essential role in proper temporal control of the EBV lytic life cycle.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a human gammaherpesvirus that infects lymphocytes, monocytes, and epithelial cells (36, 52, 68). It is associated with lymphomas, such as Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma, and immunoblastic lymphomas; carcinomas, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma and gastric carcinoma (5, 6, 16, 18, 57, 67); and benign diseases, such as infectious mononucleosis (32). The virus has two distinct life styles: latency, during which a limited number of genes are expressed; and the lytic cycle, when the majority of viral genes are expressed and virions are produced. While genes expressed during latency are sufficient to induce the oncogenic effect of the virus, the lytic cycle is essential for the virus to spread between cells and individuals. The switch from the latent to the lytic life cycle of the virus is controlled by two immediate-early proteins: ZEBRA (also called EB1 and Zta), encoded by the BZLF1 gene; and Rta, encoded by the BRLF1 gene (10, 11, 20, 31). Both transcription factors are expressed simultaneously following induction of the lytic cycle (29, 58, 61). Each protein activates a separate class of EBV lytic cycle genes, and together the two proteins synergize to activate a third class of lytic cycle genes (48). The synergistic effect of ZEBRA or Rta on a specific promoter requires the presence of at least one responsive element for each of the two immediate-early proteins (46).

ZEBRA, a member of the bZIP family of transcription factors, plays an indispensable role in driving the lytic cycle of EBV. ZEBRA is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein that forms a homodimer via its pseudo-leucine-zipper dimerization domain. ZEBRA recognizes canonical AP-1 sites, as well as a spectrum of 7-bp sequences termed ZEBRA response elements (ZREs) (40). ZEBRA triggers the switch from the latent to the lytic state by binding to ZREs in promoters of viral and cellular genes and activating their transcription (19, 23, 65). The direct interaction of ZEBRA with responsive promoters has been demonstrated by using both in vitro and in vivo DNA binding assays (7, 15, 39, 41, 43, 64).

Transcriptional activation of responsive genes by ZEBRA requires that the viral protein interacts with several cellular proteins. The protein directly interacts with TATA binding protein and components of the TFIIA complex via its activation domain. The activation domain of ZEBRA stabilizes the TFIIA-TFIID complex and recruits the TFIIB complex, which further stabilizes the preinitiation complex (8, 42). The transcriptional activity of ZEBRA is also dependent on the ability of ZEBRA to recruit CREB binding protein (1, 71), a transcriptional coactivator that possesses intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity.

ZEBRA is also indispensable for lytic viral DNA replication. The protein binds to multiple motifs in oriLyt, (30, 41, 53, 54). The minimum lytic viral DNA replication machinery in EBV consists of ZEBRA plus six EBV-encoded replication proteins (22). ZEBRA physically interacts with three of these proteins: the viral DNA polymerase (BALF5) (3), the DNA polymerase processivity factor (BMRF1) via its DNA binding domain (73), and the helicase-primase complex (BBLF4-BSLF1:BBLF2/3) via its activation domain (26). The latter interactions suggest that ZEBRA might recruit and stabilize the replisome on oriLyt.

As in other herpesviruses, progression from the early to the late stage of EBV gene expression during the lytic cascade is contingent on viral DNA replication (56). Inhibition of viral DNA synthesis by inhibitors of viral DNA polymerase blocks expression of late genes (49, 60). However, the mechanism by which DNA viral replication stimulates expression of late genes is complex. In EBV, derepression of late gene expression does not seem to require replication of the template strand; i.e., the requirement for DNA replication is trans acting (56). Thus, mechanisms that control expression of EBV late genes are not limited to displacement of repressing proteins or to demethylation of the template DNA. The importance of EBV immediate-early proteins in controlling late gene expression is demonstrated by the capacity of Rta to directly activate expression of two late proteins, BLRF2, a component of virions (55), and gp350 (BLLF1a), the major viral envelope glycoprotein that interacts with the EBV receptor CD21 (21). This activity of Rta does not require ZEBRA expression or viral DNA replication (20, 48). In cell lines in which viral replication is blocked, either due to a deletion of the viral genome encompassing the viral single-stranded DNA binding protein (BALF2), as in Raji cells (14), or due to treatment with phosphonoacetic acid (PAA), a viral DNA polymerase inhibitor, as in HH514-16 cells, coexpression of ZEBRA and Rta abolishes the activation of BLRF2 (48). This finding implies the existence of additional temporal control mechanisms on late gene expression. One immediate-early protein, ZEBRA, represses the activity of a second immediate-early protein, Rta, and inhibits it from stimulating the expression of a specific class of late proteins at early times in the lytic cycle. In this report, we explore the hypothesis that posttranslational modification of ZEBRA plays an essential role in its capacity to repress Rta's action on late genes.

ZEBRA is a phosphoprotein (4, 12, 17). The primary amino acid sequence of ZEBRA reveals consensus sequences for phosphorylation by protein kinase C (PKC) at T159 and S186 and for phosphorylation by casein kinase 2 (CK2) at S167 and S173. ZEBRA can be phosphorylated in vitro by several isoforms of PKC and by CK2 at their respective consensus sequences (4, 17, 38). However, the physiologic consequences of phosphorylation of ZEBRA at these sites in vivo remain unknown. Although activation of PKC enhances the phosphorylation of ZEBRA (4), tissue culture studies demonstrated that neither T159 nor S186 is constitutively phosphorylated in vivo in the absence of PKC agonists (17). Moreover phosphorylation of ZEBRA at these two residues is not required for ZEBRA to initiate the viral lytic cycle (17). In this report, we demonstrate that ZEBRA is constitutively phosphorylated in vivo at the CK2 substrate motif and we show that phosphorylation of this motif is essential for ZEBRA to act as a repressor of an Rta-responsive late gene, BLRF2, during the early phase of the lytic cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

Raji is an EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma cell line that carries a nonreplicating viral genome due to a deletion that spans the gene encoding the major DNA binding protein (BALF2), which is an essential component of the viral replication machinery (14). HH514-16 (Cl16) is a subclone of the P3J-HR1 Burkitt's lymphoma cell line. This cell line is tightly latent and carries a viral genome that can be fully induced into lytic replication (33). Both cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplied with 8% fetal calf serum, amphotericin B (Fungizone), and antibiotics.

Eukaryotic expression vectors and transient transfections.

The open reading frame of the gene encoding ZEBRA, BZLF1, was cloned into the pHD1013 vector under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early promoter (13). The Z(S186A) and the Rta expression vectors were previously described (25, 47). An expression vector encoding Myc-tagged ZEBRA was generated by amplifying genomic BZLF1 from pHD1013/gZ expression vector. Two sets of primers were used in the PCR: the first primer was complementary to the 5′ end of BZLF1 and contained a BglII recognition sequence, while the second primer was complementary to the 3′ end of BZLF1, and carried Myc tag and BamHI recognition sequences. The amplified BZLF1 gene was cloned into pBXG1 and was expressed under the control of the SV40 promoter. Additional point mutations were generated by using the Quick Change site-directed mutagenesis system (Stratagene). Sequences of the mutagenic primers are available upon request. Unless otherwise stated, 10 μg of plasmid DNA was used to transfect 107 cells. After incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, the cells were harvested and resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer at a concentration of 106 cells/10 μl. To study the effect of DRB (5,6-dichloro-1-β-d-ribofuranosyl-benzimidazole; Calbiochem) on repression, the inhibitor was added 20 h after transfection and the cells were collected after an additional 20 h.

Analysis of EBV lytic genes.

Fifteen microliters containing an extract of 1.5 × 106 cells was loaded on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel for analysis. The separated proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used to detect ZEBRA (63), Rta (47), and BLRF2 (35). The SJ human serum was used to detect BFRF3 and EBNA1 (55). These antibodies were diluted 1:100 in 5% (wt/vol) powdered milk. The EA-D (early antigen diffuse) protein was detected by a mouse monoclonal antibody (R3) at a dilution of 1:1,000 in 5% milk (9). The protein-antibody complex was visualized by addition of 125I-labeled protein A (1 μCi).

Prokaryotic expression and purification of ZEBRA.

Bacterial expression vectors of Z(S167A) and Z(S173A) were generated by introducing single-point mutations in the pET-22b/cDNA ZEBRA construct by using the Quick Change site-directed mutagenesis system (Stratagene). The preparation of the template DNA, pET-22b/cDNA ZEBRA, was described previously (24). pET-22b/cDNA Z(S167A) was used as a template to generate the bacterial plasmid encoding Z(S167A/S173A). The expression of wild-type ZEBRA and the various ZEBRA mutants in Escherichia coli (BL21) was induced for 2 h by adding IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) to a final concentration of 1 mM. Cell extracts were prepared in 6 M urea, and the ZEBRA proteins were purified on nickel columns as detailed previously (17). The homogeneity of the purified proteins was confirmed by Coomassie blue or silver nitrate staining of column fractions resolved by SDS-PAGE. Purified ZEBRA proteins were refolded by stepwise dialysis against decreasing concentrations of urea in 15 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 75 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 15% glycerol.

In vitro phosphorylation of ZEBRA.

Phosphorylation of ZEBRA by CK2 was examined by incubating 250 ng of purified recombinant ZEBRA with 0.3 μg of recombinant CK2 holoenzyme (Calbiochem). The phosphorylation reaction was carried out in CK2 phosphorylation buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 125 mM KCl) in the presence of 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP. The reaction mixture was incubated for 10 min at 30°C. SDS-polyacrylamide gel sample buffer was added to stop the reaction. The extent of phosphorylation of wild-type ZEBRA and ZEBRA mutants was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. Inhibition of ZEBRA phosphorylation by CK2 was performed with DRB (Biomol) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at the indicated concentrations.

Metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitation.

HH514-16 cells (1.5 × 107) were transfected with 15 μg of plasmid DNA. Twelve hours after transfection, the cells were washed with RPMI 1640 medium lacking phosphate or methionine and cysteine for 32P and 35S labeling, respectively (ICN). The cells were incubated with 1.6 mCi of [γ-32P]orthophosphate or with 0.45 mCi of [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine for 6 h at 37°C. The cells were washed in Tris-buffered saline and resuspended in 200 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.25 M NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 0.1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg of aprotinin per ml). ZEBRA was immunoprecipitated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the N-terminal domain of ZEBRA (63). The ZEBRA-antibody complex was captured with a mixture of protein A-protein G-coated agarose beads. The immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE (8% polyacrylamide), and the gel was dried and autoradiographed.

Tryptic peptide mapping and phosphoamino acid analysis.

The radiolabeled band corresponding to ZEBRA was excised from an SDS-PAGE gel. The protein was extracted in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.2% SDS. ZEBRA was precipitated with cold trichloroacetic acid (20%) in the presence of 20 μg of bovine serum albumin as a carrier. The precipitated pellet was washed with 95% cold ethanol. ZEBRA was then digested with 20 μg of trypsin (Promega) at 37°C for 24 h. The tryptic peptides were separated on thin-layer cellulose (TLC) in two dimensions. The first dimension involved horizontal electrophoresis at 1,000 V for 25 min in pH 1.9 buffer (2.5% [vol/vol] formic acid, 7.8% [vol/vol] acetic acid). The second dimension was ascending thin-layer chromatography in phosphochromatography buffer (32.5% [vol/vol] n-butanol, 25% [vol/vol] pyridine, 7.5% [vol/vol] acetic acid). Following chromatography, the plate was dried and autoradiographed.

Phosphoaminoacid analysis was performed by hydrolyzing 32P-labeled ZEBRA in 6 N HCl for 60 min at 110°C. The solution was dried in a speedVac and reconstituted in pH 1.9 buffer. Cold phosphoamino acid standards were added to the sample, and the mixture was subjected to thin-layer electrophoresis in two dimensions: the first in pH 1.9 buffer and the second in pH 3.5 buffer (5% [vol/vol] acetic acid, 0.5% [vol/vol] pyridine). The plate was dried, sprayed with 5% ninhydrin (Sigma) dissolved in methanol, and incubated at 65°C for 5 min. Radiolabeled amino acids were visualized by autoradiography, and their positions were compared with those of the unlabeled reference phosphoamino acids.

RESULTS

CK2 phosphorylates ZEBRA in vitro at two sites, S167 and S173.

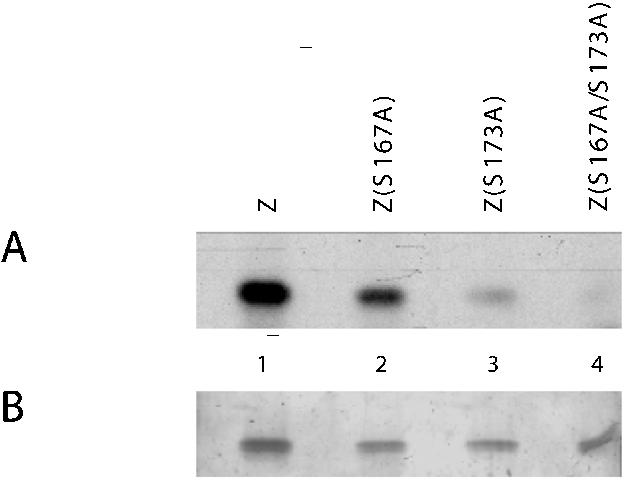

Using purified recombinant His-tagged ZEBRA proteins and purified recombinant CK2, the level of in vitro phosphorylation of wild-type ZEBRA was compared with that of ZEBRA proteins in which S167 and S173 were mutated to alanine (Fig. 1). Silver nitrate staining indicated that equal amounts of ZEBRA proteins were used in the reactions (Fig. 1B). The level of ZEBRA phosphorylation by CK2 decreased markedly when S173 was mutated to alanine (lane 3). Although changing S167 to alanine did not result in a marked drop in ZEBRA phosphorylation, mutation of both S167 and S173 to alanine nearly eliminated phosphorylation of ZEBRA by CK2 (lane 4). This result confirmed previous studies in which unpurified TrpE-ZEBRA fusion protein present in E. coli extracts and in vitro-translated ZEBRA were found to be phosphorylated in vitro at S167 and S173 by CK2 partially purified from bovine liver (38).

FIG. 1.

In vitro phosphorylation of ZEBRA by CK2. Purified recombinant wild-type ZEBRA (Z), Z(S167A), Z(S173A), and Z(S167A/S173A) proteins were incubated with purified recombinant CK2 in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The reaction mixtures were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide), and the gel was stained with silver nitrate (B). The extent of 32P labeling of each protein was determined by autoradiography after drying the gel (A).

ZEBRA is phosphorylated at the S167/S173 CK2 sites in vivo.

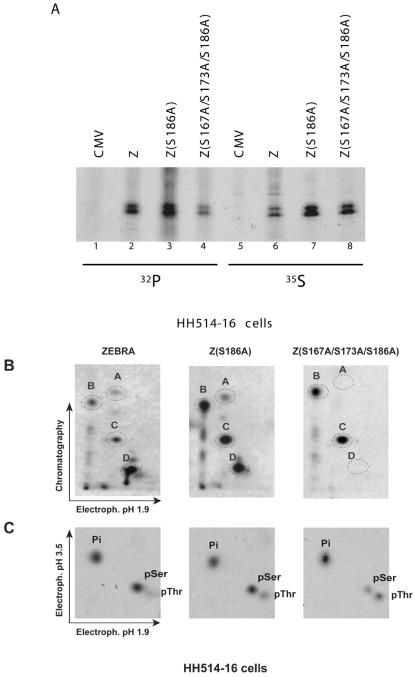

To determine whether ZEBRA was phosphorylated in vivo at S167 and S173 in the presence of the intact EBV genome, metabolic labeling experiments were carried out in HH514-16 cells, a prototype EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma-derived cell line (33). To exclude phosphopeptides attributable to endogenous ZEBRA, S167A and S173A mutations were installed in the background of Z(S186A), a mutant that is incompetent to initiate the lytic cycle and consequently unable to activate the expression of endogenous ZEBRA (24, 25). The constitutive phosphopeptide patterns of wild-type ZEBRA and Z(S186A) in the HH514-16 cell background are identical (17). HH514-16 cells transfected with empty vector or ZEBRA expression vectors were labeled with a mixture of [35S]cysteine and [35S]methionine or with [32P]orthophosphate for 6 h. Radioactively labeled ZEBRA proteins were immunoprecipitated with a specific antibody against the transactivation domain of ZEBRA, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. This strategy allowed us to compare the relative levels of phosphorylation and expression of wild-type and mutant ZEBRA proteins (Fig. 2A). After autoradiography of 35S-labeled immunoprecipitates it was found that ZEBRA mutants that carried an alanine substitution at S186 were expressed to higher levels than wild-type ZEBRA (compare lanes 7 and 8 with lane 6). However, 32P labeling indicated that mutations of S167 and S173 to alanine reduced but did not abolish the overall level of phosphorylation (compare lane 4 with lane 3).

FIG. 2.

Mutations at S167 and S173 alter the phosphorylation state of ZEBRA in vivo. (A) Immunoprecipitation of metabolically labeled ZEBRA. HH514-16 cells were transfected with empty vector (CMV) or expression vectors encoding wild-type ZEBRA (Z), Z(S186A), and Z(S167A/S173A/S186A). Fifteen hours after transfection, the cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate or a mixture of [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine. The in vivo-labeled ZEBRA proteins were immunoprecipitated and separated by SDS-PAGE (8% polyacrylamide), and the ZEBRA bands were identified by autoradiography. (B) Tryptic phosphopeptide maps of wild-type ZEBRA and the CK2 site mutants. Gel slices containing ZEBRA polypeptides were excised, and the protein was extracted and subjected to trypsin digestion. The phosphorylated peptides were detected by autoradiography after separation on TLC plates in two dimensions. The major phosphopeptides are circled and designated with the letters A to D. (C) Phosphoaminoacid analysis of in vivo-labeled ZEBRA proteins in the absence and presence of mutations at S167 and S173. A fraction of each tryptic digest was hydrolyzed with 6 N HCl and separated by electrophoresis on TLC plates in two dimensions. The radioactive phosphoamino acids were identified by virtue of comigration with nonradioactive phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, and phosphotyrosine, which were stained with ninhydrin. Pi, free phosphate; pSer, phosphoserine; pThr, phosphothreonine.

To confirm that the observed reduction in the overall phosphorylation level of the Z(S167A/S173A/S186A) mutant was due to elimination of phosphorylation sites, we compared the in vivo phosphopeptide maps of wild-type and mutant ZEBRA proteins (Fig. 2B). Four main phosphopeptides were observed in peptide maps of wild-type ZEBRA and Z(S186A). Mutations at S167 and S173 resulted in the disappearance of two spots (A and D). The relative intensities of the two other peptides (B and C) were not affected by mutations at the CK2 sites.

We also compared the phosphoamino acid composition of wild-type and mutant ZEBRA proteins (Fig. 2C). ZEBRA was found to be phosphorylated on serines and threonines, but not on tyrosines. Higher levels of phosphoserine than phosphothreonine were present in wild-type ZEBRA and the Z(S186A) mutant. Mutations of S167 and S173 to alanine markedly reduced the intensity of the phosphoserine spot but did not affect that of phosphothreonine. The results of phosphopeptide and phosphoamino acid analyses indicated that ZEBRA is phosphorylated at S167 and S173 in vivo, but additional phosphorylation sites on both serines and threonines exist.

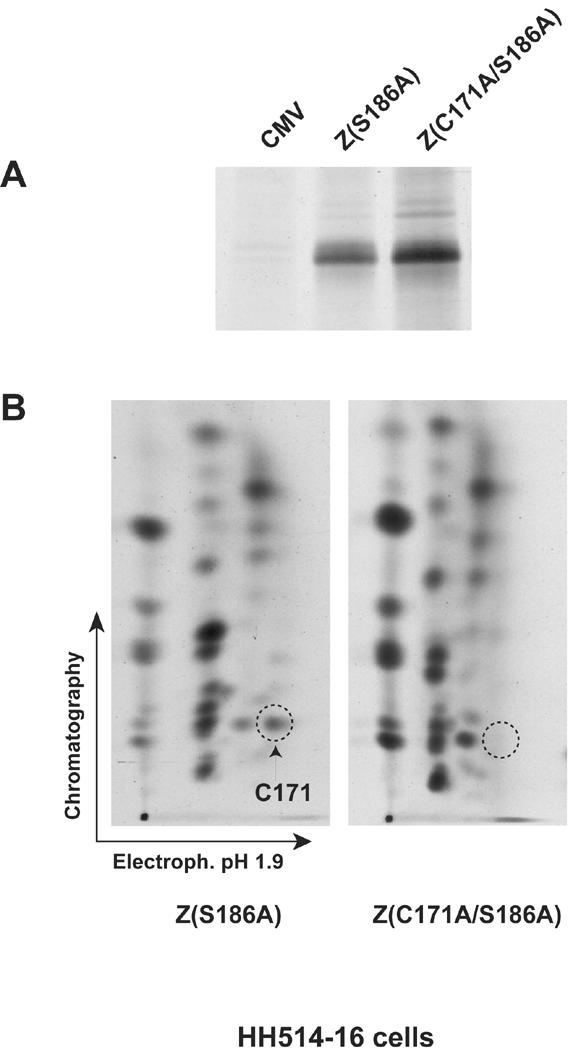

Replacement of C171 with alanine identifies the tryptic peptide that contains S167 and S173.

Mutations of S167 and S173 to alanine resulted in the disappearance of two spots from the phosphopeptide map of ZEBRA (Fig. 2B). The disappearance of a spot from the phosphopeptide map of a protein upon the replacement of S, T, or Y with alanine provides evidence that this peptide is phosphorylated in vivo. However, a spot might also disappear if, for example, the mutation alters the conformation of the protein and disrupts its interaction with a kinase that phosphorylates the protein at a different site. To determine whether mutations at S167 and S173 affected primary phosphorylation sites, we characterized the migration of the tryptic peptide that encompasses the two CK2 substrate sites. As no lysine or arginine residues are present between S167 and S173, the two residues are located on the same tryptic peptide. This tryptic peptide can be detected in a peptide map of 35S-labeled ZEBRA due to the presence of a cysteine residue at position 171. We compared the migration of 35S-labeled tryptic peptides of Z(S186A) and Z(C171A/S186A) with phosphopeptides A and D, the phosphopeptides that disappeared when S167 and S173 were mutated to alanine (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

The 35S-labeled tryptic peptide that contains S167 and S173 migrates at the same position as phosphopeptide D. (A) Immunoprecipitation of ZEBRA from HH514-16 cells transfected with empty vector (CMV) or expression vectors encoding Z(S186A) or Z(C171A/S186A) and labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine. The immunoprecipitated products were separated on an 8% polyacrylamide-SDS gel, and the ZEBRA bands were visualized by autoradiography. (B) Tryptic peptide maps of Z(S186A) and Z(C171A/S186A) labeled with 35S. The dashed circle indicates the position of the tryptic peptide that contains C171, S167, and S173.

Mutation of C171 to alanine resulted in the disappearance of a major 35S spot that corresponds to the S167/C171/S173 tryptic peptide (Fig. 3B). The migration of the 35S-C171-labeled tryptic peptide on the two-dimensional TLC plate was similar to the migration of phosphopeptide D. Since no serine or threonine residues other than S167 and S173 are found on this tryptic peptide, the result suggests that mutations of these two serines directly affect the phosphorylation of ZEBRA at these residues. However, the C171A mutation did not result in elimination of a 35S-labeled tryptic peptide that corresponds in mobility to phosphopeptide A (see Discussion).

Mutations at S167 and S173 specifically disrupt the capacity of ZEBRA to repress activation of the LR2 gene.

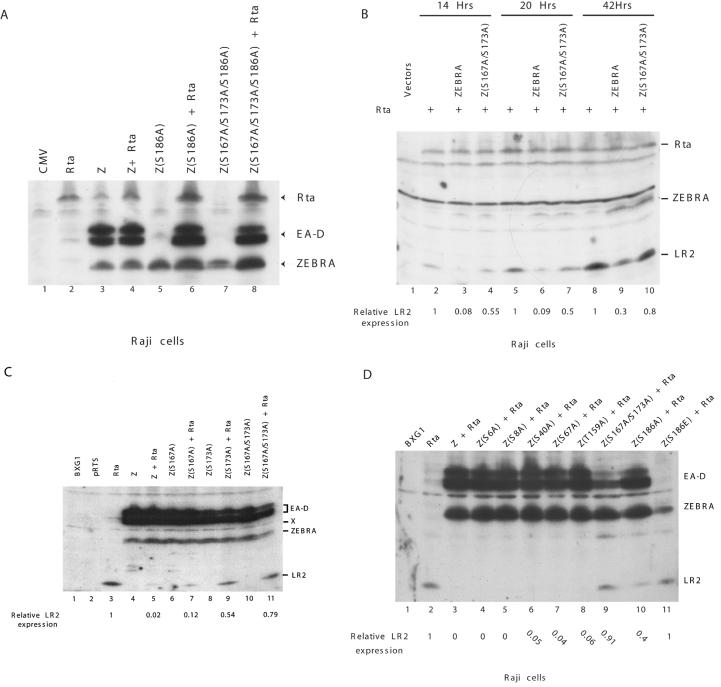

The next series of experiments discovered a phenotype associated with the phosphorylation of ZEBRA at the CK2 substrate motif. The Z(S167A/S173A) mutant, when transfected into Raji cells, could activate the early lytic cycle gene BMRF1, encoding the DNA polymerase processivity protein, albeit at slightly lower levels. We examined the capacity of the mutant Z(S167A/S173A) to carry out two additional functions of ZEBRA: (i) synergy with Rta and (ii) repression of Rta-mediated activation of the late gene BLRF2.

The effect of the CK2 site mutations on the synergy function of ZEBRA with Rta was examined in Raji cells (Fig. 4A). In this cell background, Rta does not activate its own expression or that of ZEBRA (48). Rta alone activates barely detectable levels of EA-D, the protein encoded by the BMRF1 gene (Fig. 4A, lane 2). The Z(S186A) mutant is totally impaired in activation of EA-D (25) (Fig. 4A, lane 5). However, Rta plus Z(S186A) strongly synergize, resulting in expression levels of EA-D that are comparable to levels induced by wild-type ZEBRA, which induces Rta from the latent viral genome (compare lane 6 with lanes 3 and 4) (2, 24). When the CK2 site mutations were installed into the background of Z(S186A), they behaved like Z(S186A) itself. The Z(S167A/S173A/S186A) mutant was unable to induce EA-D (lane 7) but could synergize with Rta (lane 8). From this experiment, we conclude that the CK2 site mutants do not affect the role of ZEBRA in synergistic activation of an early-lytic-cycle gene.

FIG. 4.

Mutations of the CK2 phosphorylation motif in ZEBRA specifically abolish its ability to suppress activation of BLRF2 (LR2) by Rta. (A) Mutations S167A and S173A do not affect the capacity of ZEBRA to synergize with Rta in activation of EA-D in Raji cells. (B) The Z(S167A/S173A) mutant is deficient in repressing Rta activation of LR2. Raji cells were transfected with Rta and either wild-type ZEBRA (Z) or the Z(S167A/S173A) mutant. Extracts prepared at different times after transfection were assessed for expression of the LR2 product by immunoblotting. (C) Effect of single-point mutations in the CK2 site on the capacity of ZEBRA to act as a repressor of Rta. Extracts of transfected Raji cells were examined for LR2 protein 30 h after transfection. (D) Mutations at several other serine and threonine residues in its activation domain did not alter the competence of ZEBRA to repress LR2 expression. In all experiments, the membranes were immunoblotted with antibodies against EA-D, ZEBRA, Rta, and BLRF2 protein (LR2).

The effect of mutations of the CK2 sites, S167 and S173, on the ability of ZEBRA to block Rta activation of the late gene BLRF2 was also examined in Raji cells (Fig. 4B). The EBV genome in Raji cells carries a deletion that spans the gene encoding the viral major DNA binding protein, BALF2 (14). Therefore, viral late gene expression, which is dependent on viral DNA replication, does not occur in Raji cells. However, transient expression of Rta in Raji cells bypasses the requirement for viral DNA replication and stimulates the expression of the late protein BLRF2 (LR2). ZEBRA represses the activation of LR2 by Rta (48). The repressor functions of wild-type ZEBRA and the CK2 site mutants were compared (Fig. 4B). At each of three time points after transfection of Raji cells, Rta activated LR2 (Fig. 4B lanes 2, 5 and 8) and wild-type ZEBRA repressed this activity (Fig. 4B lanes 3, 6 and 9). The mutant Z(S167A/S173A) was markedly reduced in its capacity to act as a repressor (Fig. 4B lanes 4, 7, and 10). At early times after transfection, wild-type ZEBRA was five- to sevenfold-more effective as a repressor than the CK2 site double mutant.

We evaluated the effect of individually mutating each of the two serines in the CK2 motif on the capacity of ZEBRA to repress LR2 expression induced by Rta (Fig. 4C). Wild-type ZEBRA blocked Rta-induced expression of LR2 by 98% compared to the level of LR2 observed in the presence of Rta and the absence of ZEBRA (compare lanes 5 and 3). Based on densitometry, the repressive activity of the Z(S167A) mutant was reduced about 6-fold, that of the S173A mutant was reduced about 27-fold, and that of the double mutant was reduced about 40-fold. None of the CK2 site mutants reproducibly affected the expression level of ZEBRA (Fig. 4B and C) (data not shown). Mutants with S173A were only slightly less active than the wild type in activating EA-D early gene expression.

To learn whether the CK2 site mutations were specific in their impairment for the repressive function of ZEBRA, we studied the effect of five other serine- or threonine-to-alanine substitutions on the capacity of ZEBRA to disrupt latency and to repress Rta (Fig. 4D). ZEBRA mutants with alanine substitutions at S6, S8, S40, S67, and T159 behaved like the wild type. They repressed the expression of LR2 by more than 94%. However in the same experiment, the mutant Z(S167A/S173A) did not significantly repress the action of Rta. These results demonstrated that the loss of repression by mutations at S167 and S173 is specific to these residues.

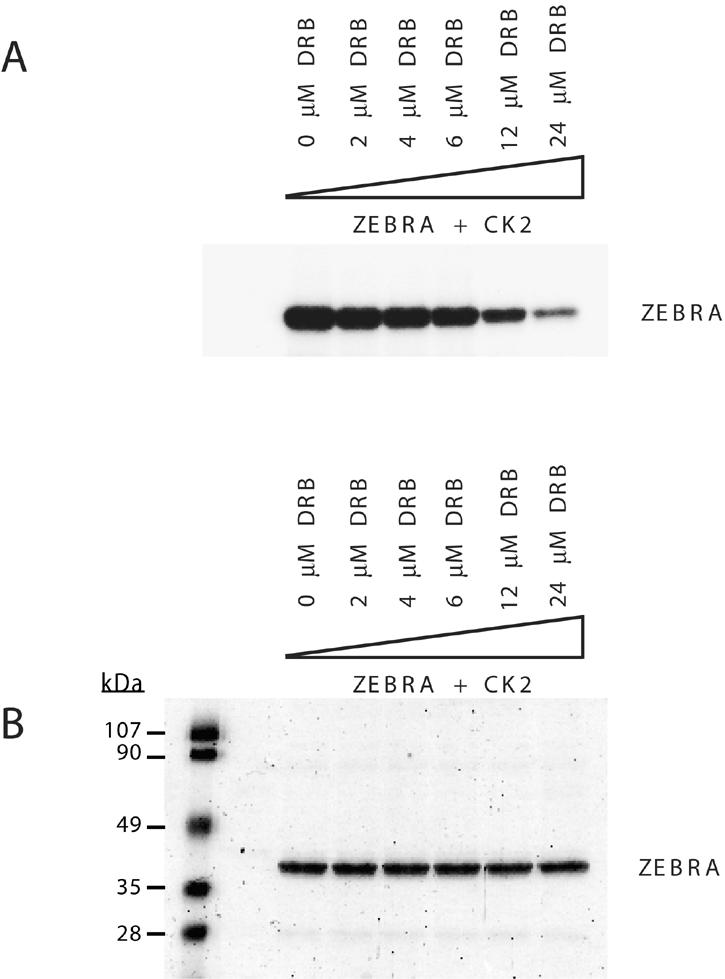

ZEBRA phosphorylation by CK2 is crucial for its repression function.

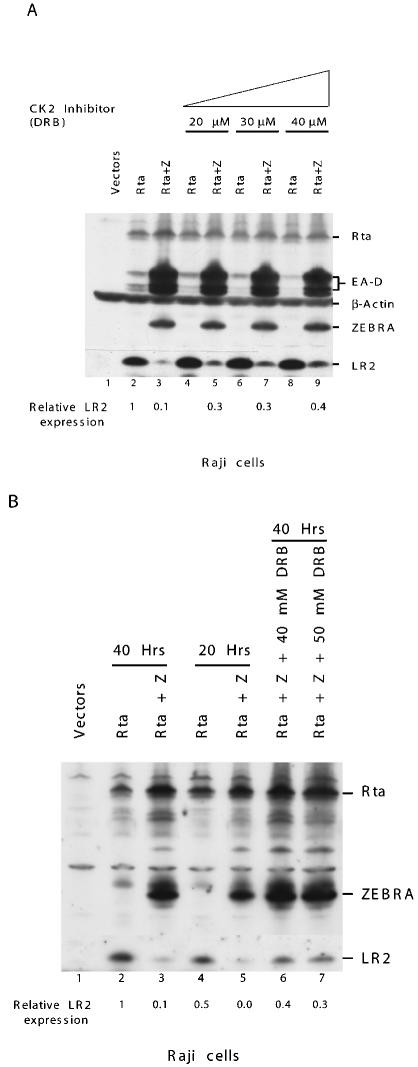

Since mutations of the CK2 sites could alter the conformation of ZEBRA, we sought further evidence of the importance of phosphorylation of ZEBRA by CK2 by use of a specific inhibitor, DRB (37). Initially, we found that DRB blocked the phosphorylation of ZEBRA by CK2 in vitro (Fig. 5). A Coomassie blue stain of the gel showed that equal amounts of recombinant ZEBRA were phosphorylated in each reaction (Fig. 5B). Autoradiography indicated a direct relationship between the concentration of the inhibitor and the level of phosphorylation. As the concentration of the inhibitor increased, the level of phosphorylated ZEBRA by CK2 diminished (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

DRB inhibits CK2 phosphorylation of ZEBRA in vitro. Purified recombinant CK2 was incubated with 250 ng of purified bacterially expressed ZEBRA and [γ-32P]ATP. The phosphorylation level of ZEBRA was assessed in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of the specific CK2 inhibitor DRB. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 15 min at 37°C, and the phosphorylated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide). The gel was stained with Coomassie blue (B) and dried and autoradiographed (A).

To examine the effect of DRB on the function of ZEBRA in vivo, Raji cells were transfected with Rta or Rta plus ZEBRA. The inhibitor was added after 8 h, and cell extracts were monitored for viral protein expression after 30 h (Fig. 6A). The inhibitor did not affect the capacity of Rta to activate expression of LR2 (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). Nor did the inhibitor affect the expression of Rta or ZEBRA or the induction of EA-D. However, DRB impaired the capacity of ZEBRA to repress activation of LR2 2.5- to 3.5-fold. Cotransfection of ZEBRA and Rta in the absence of DRB inhibited LR2 expression by 89% (lane 3).

FIG. 6.

The CK2 inhibitor DRB restores the ability of Rta to activate LR2 expression in the presence of wild-type ZEBRA. Ten micrograms of plasmid DNA was transfected into 107 Raji cells. The DNA contained equal amounts of Rta plus ZEBRA expression vector or Rta expression vector plus empty vector. Eight hours after transfection, the cells were treated with the CK2 inhibitor. Cells were harvested after a total period of 30 h, and extracts were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting for the indicated proteins. (A) Concentrations of DRB from 20 to 40 μM inhibit ZEBRA's ability to repress activation of LR2 by Rta. (B) Cells were harvested either 40 h (lanes 2 and 3) or 20 h (lanes 4 and 5) after transfection, and the level of LR2 expression was compared with that of cells treated with the inhibitor between h 21 and 40 (lanes 6 and 7). The numbers at the bottom of each figure represent the relative level of LR2 expression following different treatments. (The level of LR2 expression in the absence of any treatment was equal to 1.)

In the experiment illustrated in Fig. 6A, the inhibitor did not completely abolish the repressive effect of ZEBRA on LR2 expression. This could be the result of ZEBRA acting as a repressor before h 8 of the experiment, when DRB was added. In a second experiment (Fig. 6B), Raji cells were similarly transfected with plasmids encoding Rta or Rta plus ZEBRA. One set of cells without inhibitor was harvested at 20 h, and another was harvested at 40 h after transfection. The DRB inhibitor was added to a third set between h 20 and 40. The highest level of LR2 expression was seen in cells exposed to Rta for 40 h (lane 2); a reduced level of LR2 was observed in cells exposed for 20 h (lane 4). ZEBRA strongly repressed LR2 expression in cells harvested at both times. Addition of DRB between h 20 and 40 (lanes 6 and 7) markedly reduced the repressive activity of ZEBRA. LR2 was expressed to a level comparable to that seen without ZEBRA at 20 h. This experiment suggested that during the time interval that the DRB inhibitor was present, ZEBRA did not exert any repressive effect.

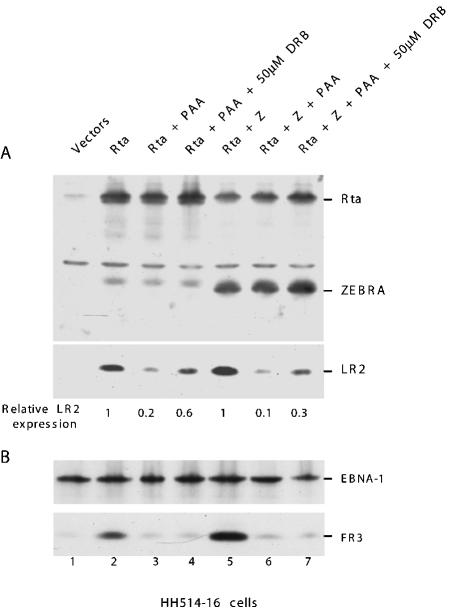

In a permissive cell line, inhibition of LR2 expression prior to viral replication is dependent on CK2.

The repression function of ZEBRA was originally discovered in Raji cells, which are nonpermissive for viral DNA replication. We next examined whether CK2 phosphorylation of ZEBRA also mediates repression of Rta's capacity to activate the BLRF2 gene in a cell line that is permissive for viral replication. For these experiments, we used the HH514-16 cell line, in which Rta is sufficient to activate the entire lytic cycle because it activates the endogenous BZLF1 gene (47). HH514-16 cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding Rta or Rta plus ZEBRA and were treated with PAA, a DNA polymerase inhibitor, in the absence and presence of 50 μM DRB (Fig. 7). Since lytic viral replication is a prerequisite for late EBV gene expression, we used expression of two late proteins, LR2 and FR3, as an indirect assay for the occurrence of viral replication. PAA inhibited expression of both late genes (compare lanes 2 and 5 with lanes 3 and 6, respectively, in Fig. 7A and B). However, addition of the CK2 inhibitor to cells blocked in viral replication released the suppressive effect mediated by ZEBRA on the expression of LR2 (Fig. 7A lanes 4 and 7). The CK2 inhibitor blocked ZEBRA-mediated repression of LR2 at early times by about 2.5-fold. The magnitude of the effect of DRB in HH514-16 cells was similar to that observed in Raji cells (Fig. 6). However, the CK2 inhibitor did not alter the expression of FR3, which likely represents a class of late genes that is regulated by a mechanism that does not involve repression by ZEBRA (Fig. 7B, lanes 4 and 7).

FIG. 7.

Inhibition of CK2-mediated phosphorylation of ZEBRA allows expression of LR2 in cells in which lytic viral DNA replication is blocked by PAA. HH514-16 cells were transfected with 5 μg of DNA containing equal amounts of Rta and ZEBRA expression vector or Rta and empty vector. The transfected cells were untreated (lanes 1, 2, and 5), treated with 0.4 mM PAA (lanes 3 and 6), or treated with 50 μM DRB together with 0.4 mM PAA (lanes 4 and 7). Cell extracts prepared 40 h after transfection were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against Rta, ZEBRA, and LR2 (A) or EBNA1 and FR3 (B).

DISCUSSION

Posttranslational modifications play an important role in regulating the activity, localization, stability, and protein-protein interaction of transcription activators (34). Information regarding the physiologic significance of in vivo phosphorylation of ZEBRA, the key EBV lytic cycle transactivator, is meager. When ZEBRA is transfected into cells, in the absence of any other EBV lytic cycle-inducing stimulus, the protein is phosphorylated (4, 12, 17). Until the present report, the sites of this constitutive phosphorylation, the responsible kinases, and any functional consequences were not known. In this study, we demonstrate that ZEBRA is constitutively phosphorylated in vivo at both serine and threonine residues (Fig. 2C); a previous report suggested that ZEBRA is phosphorylated only on serine residues (12). We identified a single tryptic peptide, containing two CK2 substrate residues, S167 and S173, that is phosphorylated in vivo (Fig. 3B). Most importantly we describe the first functional consequences of constitutive phosphorylation of ZEBRA: namely, that phosphorylation of S167/S173 plays an essential role in ZEBRA's ability to repress Rta's activation of late genes at early times in the EBV lytic cycle (Fig. 4, 6, and 7).

Phosphorylation of ZEBRA by CK2.

Additional experiments will be needed to explore the sites of interaction of CK2 with ZEBRA in vivo. CK2 is likely to interact with the basic DNA recognition domain of ZEBRA (amino acids [aa] 178 to 194) and phosphorylate residues (i.e., S167 and S173) located upstream in a “regulatory region” of the protein. Consistent with this hypothesis, a triple-point mutation in ZEBRA's basic domain (R187E/K188E/C189S) abrogated phosphorylation of ZEBRA in vitro by CK2 (38). CK2 also interacts with several cellular members of the bZIP family of transcription factors: e.g., c-Fos, c-Jun, ATF1, ATF2, and CREB (44, 66). These interactions are also mediated by the bZIP domain of these transcription factors and serve as a prerequisite for CK2-mediated phosphorylation (69). However, physical interaction between CK2 and several bZIP transcription factors, including ATF2 and CREB, is not sufficient to phosphorylate these proteins in vitro (66). Therefore, the interaction between CK2 and the bZIP domain of transcription factors might influence transcription by regulating the activity of a bZIP protein itself, via phosphorylation, or by recruiting CK2 activity to the promoter of a specific gene to which the transcription factor binds and thereafter phosphorylating other proteins bound there (69).

To determine whether the CK2 substrate sites of ZEBRA were phosphorylated in vivo, we compared phosphorylation of ZEBRA derivatives with and without mutations at positions S167 and S173. Four lines of evidence indicated that the CK2 sites were phosphorylated in vivo: (i) the overall level of phosphorylation of the mutant Z(S167A/S173A/S186A) was lower than that of wild-type ZEBRA or Z(S186A); (ii) the level of phosphoserine in the Z(S167A/S173A/S186A) mutant was decreased, but phosphothreonine was not affected; and (iii) most importantly, mutations at S167 and S173 eliminated two tryptic phosphopeptides of ZEBRA, designated spots A and D (Fig. 2B). (iv) By means of mutagenesis of C171 to alanine and 35S labeling, spot D phosphopeptide was shown to comigrate with the 35S-labeled tryptic peptide that encompasses aa 161 to 178 and therefore contains the S167/S173 site.

However, the C171A mutation did not detectably affect a 35S-labeled tryptic peptide that corresponded to phosphopeptide spot A. Spot A could represent a trypsin partial digestion product of aa 161 to 178 plus adjacent peptides that contain other cysteines. Alternatively phosphopeptide spot A may disappear as the result of conformational or other changes secondary to the S167A/S173A mutation, such as lack of phosphorylation at this site. For example, phosphopeptide A may represent phosphorylation of another site on ZEBRA that depends on a kinase whose interaction or activity is influenced by phosphorylation at the CK2 substrate site.

ZEBRA as a repressor.

Although ZEBRA is generally viewed as a transcriptional activator and an essential DNA replication protein, several reports describe an inhibitory effect of ZEBRA on the activity of other transcription factors. ZEBRA inhibits the activity of retinoic acid receptors and p53 by direct protein-protein interaction and competes with c-Jun for DNA response elements (51, 59, 72). Two previous reports demonstrate that ZEBRA has the capacity to repress activation of EBV target genes by Rta (28, 48). Using a reporter assay in HeLa cells, Giot et al. (28) showed that ZEBRA inhibits Rta activation of the Rta response element (RRE) from the viral BHLF1 promoter. Ragoczy and Miller reported that ZEBRA blocked Rta-mediated activation of the BLRF2 late gene without affecting Rta's capacity to activate early genes alone or in synergy with ZEBRA (48).

Giot et al. attributed the ability of ZEBRA to inhibit activation of the BHLF1 promoter by Rta to squelching (28). If competition between ZEBRA and Rta for an essential component of the transcription machinery, the postulated mechanism of squelching (27), is the explanation for ZEBRA's capacity to inhibit activation of BLRF2 by Rta, then squelching would need to be promoter specific. ZEBRA does not impair the capacity of Rta to activate two genes that it controls exclusively, namely BaRF1 (ribonucleotide reductase) or BMLF1 (posttranscriptional activator). Moreover, ZEBRA and Rta synergistically activate the BMRF1 (DNA polymerase processivity factor) gene (2, 25). Furthermore Giot et al. showed, as expected for squelching, that a non-DNA binding mutant of ZEBRA was competent to inhibit Rta's activation of the BHLF1 promoter (28). However, we show here (Fig. 4D) that the Z(S186E) mutant, which is deficient in DNA binding (4, 17), failed to repress Rta's activation of BLRF2. Furthermore, among many point mutants in ZEBRA's basic domain recently surveyed, eight mutants that abolished the DNA binding capacity of ZEBRA rendered the protein incapable of repressing Rta. Eleven ZEBRA mutants that remained competent to bind DNA, maintained repression (Heston et al., unpublished data). This finding suggests a correlation between DNA binding and repression and argues against squelching.

Thus, ZEBRA synergizes with Rta and represses Rta's action in a promoter-specific manner. The mechanisms of synergy and repression are not yet understood. The position of the ZRE relative to the RRE, the orientation and affinity of the ZREs and RREs might influence the relative roles played by ZEBRA and Rta at each promoter. Cellular proteins recruited to each promoter would also be expected to affect the function of each of the two immediate-early viral proteins. These proteins might include kinases or phosphatases that affect the phosphorylation state of ZEBRA or Rta. These posttranslational modifications in turn may be important for specific protein-protein interactions and control recruitment of coactivators or corepressors to specific promoters.

Role of phosphorylation of ZEBRA at the CK2 motif in repression.

Several lines of evidence illustrate the importance of phosphorylation at the CK2 substrate motif on the capacity of ZEBRA to serve as a repressor. Mutant forms of ZEBRA that are unable to be phosphorylated by CK2 were deficient in repression of Rta's activation of late genes (Fig. 4). The extent of deficiency in repression of each mutant correlated with the intensity of phosphorylation of ZEBRA by CK2 in vitro at the mutated site (Fig. 1A). S167, which is a minor phosphorylation site, was only slightly affected in its capacity to repress when mutated to alanine (Fig. 4C, lane 7). S173, which is the major phosphoacceptor site, was markedly reduced in its repressor function. A combination of both mutations produced the highest impact on ZEBRA's capacity to suppress Rta (Fig. 4C, lanes 9 and 11). The link between phosphorylation of ZEBRA at the CK2 substrate motif and repression was further established by use of DRB, an inhibitor of CK2 (37, 70). Treatment of Raji cells coexpressing wild-type ZEBRA and Rta with DRB reduced ZEBRA's ability to repress the BLRF2 late gene while not affecting the synergistic activation of the EBV early gene, BMRF1, by ZEBRA and Rta (Fig. 6). Thus, DRB recapitulated the EBV lytic gene expression patterns observed with the Z(S167A/S173A) mutant.

DRB is known to inhibit another kinase, CDK9, which phosphorylates the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II at serine 2 and serine 5 in the heptad repeat sequence (YSPTSPS) (45, 74). Phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain enhances RNA elongation. Since, in our experiments, DRB produces a gain-of-function phenotype on BLRF2 expression, it is unlikely that DRB inhibits transcriptional elongation of that gene. Moreover, the site of phosphorylation by CDK9 on CTD does not resemble the CK2 sites on ZEBRA.

The importance of CK2 phosphorylation of ZEBRA in repressing Rta's activation of late genes was initially demonstrated in Raji cells. In this cell background, there is no lytic viral DNA replication; thus the temporally aberrant activation of the BLRF2 late gene by Rta was readily manifest. But our experiments also show that CK2-mediated phosphorylation of ZEBRA is also critical in a permissive Burkitt's lymphoma cell line, HH514-16 (Fig. 7). In this cell background, transfection of either ZEBRA or Rta is sufficient to initiate the entire EBV lytic cycle (11, 47, 50, 62). In the presence of both activators, there is no inhibition of BLRF2 expression unless viral DNA replication is inhibited by PAA (48). These observations prompt the hypothesis that the ability of ZEBRA to inhibit activation of late genes by Rta in fully permissive cells might be temporally regulated.

To begin to test this hypothesis, we examined the role of CK2 in the permissive HH514-16 cell background when lytic viral DNA replication was inhibited by PAA. In the presence of PAA but in the absence of the CK2 inhibitor, DRB, there was no expression of BLRF2 (Fig. 7A, lanes 3 and 6); however, the addition of DRB, even in the presence of PAA, released BLRF2 expression (Fig. 7A, lanes 4 and 7). This and other results (Fig. 6) show that the CK2 inhibitor, DRB, produces a gain of function and are consistent with a model in which CK2 phosphorylation of ZEBRA is involved in temporal control of late gene expression.

Role of phosphorylation of ZEBRA at the CK2 substrate motif on the EBV life cycle.

Our experiments suggest a seminal role for phosphorylation of ZEBRA in maintaining proper temporal and sequential control of viral lytic cycle gene expression during the EBV life cycle. Our experiments further suggest that phosphorylation of ZEBRA at the CK2 substrate motif is not required for early gene activation or synergy with Rta. However this phosphorylation is required for ZEBRA to repress certain late genes at early times in the viral lytic cycle. These results prompt a series of questions that are being addressed by other current experiments. Why is it essential to repress certain late genes during the early phase of the viral lytic cycle? The presence of structural proteins in the absence of viral replication could directly inhibit virus maturation or could have immunological consequences that are deleterious to viral maturation. It will be essential to determine whether phosphorylation of ZEBRA at the CK2 sites plays a role in viral DNA replication, activation or repression of other late genes, and virus release. A major unanswered question is how lytic viral DNA replication might overcome the repressive effect of ZEBRA on Rta-mediated activation of late genes. One hypothesis that deserves intense exploration is that following lytic viral replication, ZEBRA becomes dephosphorylated at the CK2 sites and thereafter loses its repressive activity on late gene expression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jill Countryman, Anthony Koleske, Tobias Ragoczy, and Tricia Serio for helpful critiques of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA12055 and CA16038 to George Miller.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamson, A. L., and S. Kenney. 1999. The Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 protein interacts physically and functionally with the histone acetylase CREB-binding protein. J. Virol. 73:6551-6558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamson, A. L., and S. C. Kenney. 1998. Rescue of the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 mutant, Z(S186A), early gene activation defect by the BRLF1 gene product. Virology 251:187-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumann, M., R. Feederle, E. Kremmer, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1999. Cellular transcription factors recruit viral replication proteins to activate the Epstein-Barr virus origin of lytic DNA replication, oriLyt. EMBO J. 18:6095-6105. (Erratum, 19:315, 2000.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumann, M., H. Mischak, S. Dammeier, W. Kolch, O. Gires, D. Pich, R. Zeidler, H. J. Delecluse, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1998. Activation of the Epstein-Barr virus transcription factor BZLF1 by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced phosphorylation. J. Virol. 72:8105-8114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beral, V., T. Peterman, R. Berkelman, and H. Jaffe. 1991. AIDS-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet 337:805-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calne, R. Y., K. Rolles, D. J. White, S. Thiru, D. B. Evans, P. McMaster, D. C. Dunn, G. N. Craddock, R. G. Henderson, S. Aziz, and P. Lewis. 1979. Cyclosporin A initially as the only immunosuppressant in 34 recipients of cadaveric organs: 32 kidneys, 2 pancreases, and 2 livers. Lancet ii:1033-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, Y.-N., D. L.-Y. Dong, G. S. Hayward, and S. D. Hayward. 1990. The Epstein-Barr virus Zta transactivator: a member of the bZIP family with unique DNA-binding specificity and a dimerization domain that lacks the characteristic heptad leucine zipper motif. J. Virol. 64:3358-3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chi, T., P. Lieberman, K. Ellwood, and M. Carey. 1995. A general mechanism for transcriptional synergy by eukaryotic activators. Nature 377:254-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho, M.-S., K.-T. Jeang, and S. D. Hayward. 1985. Localization of the coding region for an Epstein-Barr virus early antigen and inducible expression of this 60-kilodalton nuclear protein in transfected fibroblast cell lines. J. Virol. 56:852-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Countryman, J., H. Jenson, R. Seibl, H. Wolf, and G. Miller. 1987. Polymorphic proteins encoded within BZLF1 of defective and standard Epstein-Barr viruses disrupt latency. J. Virol. 61:3672-3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Countryman, J., and G. Miller. 1985. Activation of expression of latent Epstein-Barr herpesvirus after gene transfer with a small cloned subfragment of heterogeneous viral DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:4085-4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daibata, M., R. E. Humphreys, and T. Sairenji. 1992. Phosphorylation of the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 immediate-early gene product ZEBRA. Virology 188:916-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis, M. G., and E. S. Huang. 1988. Transfer and expression of plasmids containing human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene 1 promoter-enhancer sequences in eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 10:6-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decaussin, G., V. Leclerc, and T. Ooka. 1995. The lytic cycle of Epstein-Barr virus in the nonproducer Raji line can be rescued by the expression of a 135-kilodalton protein encoded by the BALF2 open reading frame. J. Virol. 69:7309-7314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng, Z., C.-J. Chen, M. Chamberlin, F. Lu, G. A. Blobel, D. Speicher, L. A. Cirillo, K. S. Zaret, and P. M. Lieberman. 2003. The CBP bromodomain and nucleosome targeting are required for Zta-directed nucleosome acetylation and transcription activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:2633-2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desgranges, C., H. Wolf, G. De-The, K. Shanmugaratnam, N. Cammoun, R. Ellouz, G. Klein, K. Lennert, N. Munoz, and H. Zur Hausen. 1975. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. X. Presence of Epstein-Barr genomes in separated epithelial cells of tumours in patients from Singapore, Tunisia and Kenya. Int. J. Cancer 16:7-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Guindy, A. S., L. Heston, Y. Endo, M.-S. Cho, and G. Miller. 2002. Disruption of Epstein-Barr virus latency in the absence of phosphorylation of ZEBRA by protein kinase C. J. Virol. 76:11199-11208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epstein, M. A., B. G. Achong, and Y. M. Barr.1964. Virus particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt's lymphoma. Lancet i:702-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrell, P. J., D. T. Rowe, C. M. Rooney, and T. Kouzarides. 1989. Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 trans-activator specifically binds to a consensus AP-1 site and is related to c-fos. EMBO J. 8:127-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feederle, R., M. Kost, M. Baumann, A. Janz, E. Drouet, W. Hammerschmidt, and H. J. Delecluse. 2000. The Epstein-Barr virus lytic program is controlled by the co-operative functions of two transactivators. EMBO J. 19:3080-3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fingeroth, J. D., J. J. Weis, T. F. Tedder, J. L. Strominger, P. A. Biro, and D. T. Fearon. 1984. Epstein-Barr virus receptor of human B lymphocytes is the C3d receptor CR2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:4510-4514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fixman, E. D., G. S. Hayward, and S. D. Hayward. 1992. trans-acting requirements for replication of Epstein-Barr virus ori-Lyt. J. Virol. 66:5030-5039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flemington, E., and S. H. Speck. 1990. Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 trans activator induces the promoter of a cellular cognate gene, c-fos. J. Virol. 64:4549-4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francis, A., T. Ragoczy, L. Gradoville, L. Heston, A. El-Guindy, and G. Miller. 1999. Amino acid substitutions reveal distinct functions of serine 186 of the ZEBRA protein in activation of lytic cycle genes and synergy with the Epstein-Barr virus Rta transactivator. J. Virol. 73:4543-4551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francis, A. L., L. Gradoville, and G. Miller. 1997. Alteration of a single serine in the basic domain of the Epstein-Barr virus ZEBRA protein separates its functions of transcriptional activation and disruption of latency. J. Virol. 71:3054-3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao, Z., A. Krithivas, J. E. Finan, O. J. Semmes, S. Zhou, Y. Wang, and S. D. Hayward. 1998. The Epstein-Barr virus lytic transactivator Zta interacts with the helicase-primase replication proteins. J. Virol. 72:8559-8567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gill, G., and M. Ptashne. 1988. Negative effect of the transcriptional activator GAL4. Nature 334:721-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giot, J. F., I. Mikaelian, M. Buisson, E. Manet, I. Joab, J. C. Nicolas, and A. Sergeant. 1991. Transcriptional interference between the EBV transcription factors EB1 and R: both DNA-binding and activation domains of EB1 are required. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:1251-1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gradoville, L., D. Kwa, A. El-Guindy, and G. Miller. 2002. Protein kinase C-independent activation of the Epstein-Barr virus lytic cycle. J. Virol. 76:5612-5616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammerschmidt, W., and B. Sugden. 1988. Identification and characterization of oriLyt, a lytic origin of DNA replication of Epstein-Barr virus. Cell 55:427-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hardwick, J. M., P. M. Lieberman, and S. D. Hayward. 1988. A new Epstein-Barr virus transactivator, R, induces expression of a cytoplasmic early antigen. J. Virol. 62:2274-2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henle, G., W. Henle, and V. Diehl. 1968. Relation of Burkitt's tumor-associated herpes-type virus to infectious mononucleosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 59:94-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heston, L., M. Rabson, N. Brown, and G. Miller. 1982. New Epstein-Barr virus variants from cellular subclones of P3J-HR-1 Burkitt lymphoma. Nature 295:160-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunter, T. 2000. Signaling—2000 and beyond. Cell 100:113-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz, D. A., R. P. Baumann, R. Sun, J. L. Kolman, N. Taylor, and G. Miller. 1992. Viral proteins associated with the Epstein-Barr virus transactivator, ZEBRA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:378-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kikuta, H., Y. Taguchi, K. Tomizawa, K. Kojima, N. Kawamura, A. Ishizaka, Y. Sakiyama, S. Matsumoto, S. Imai, T. Kinoshita et al. 1988. Epstein-Barr virus genome-positive T lymphocytes in a boy with chronic active EBV infection associated with Kawasaki-like disease. Nature 333:455-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim, S. J., and C. R. Kahn. 1997. Insulin stimulates p70 S6 kinase in the nucleus of cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 234:681-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolman, J. L., N. Taylor, D. R. Marshak, and G. Miller. 1993. Serine-173 of the Epstein-Barr virus ZEBRA protein is required for DNA binding and is a target for casein kinase II phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:10115-10119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kouzarides, T., G. Packham, A. Cook, and P. J. Farrell. 1991. The BZLF1 protein of EBV has a coiled coil dimerisation domain without a heptad leucine repeat but with homology to the C/EBP leucine zipper. Oncogene 6:195-204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehman, A. M., K. B. Ellwood, B. E. Middleton, and M. Carey. 1998. Compensatory energetic relationships between upstream activators and the RNA polymerase II general transcription machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 273:932-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lieberman, P. M., and A. J. Berk. 1990. In vitro transcriptional activation, dimerization, and DNA-binding specificity of the Epstein-Barr virus Zta protein. J. Virol. 64:2560-2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lieberman, P. M., and A. J. Berk. 1994. A mechanism for TAFs in transcriptional activation: activation domain enhancement of TFIID-TFIIA-promoter DNA complex formation. Genes Dev. 8:995-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lieberman, P. M., J. M. Hardwick, J. Sample, G. S. Hayward, and S. D. Hayward. 1990. The Zta transactivator involved in induction of lytic cycle gene expression in Epstein-Barr virus-infected lymphocytes binds to both AP-1 and ZRE sites in target promoter and enhancer regions. J. Virol. 64:1143-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin, A., J. Frost, T. Deng, T. Smeal, N. al-Alawi, U. Kikkawa, T. Hunter, D. Brenner, and M. Karin. 1992. Casein kinase II is a negative regulator of c-Jun DNA binding and AP-1 activity. Cell 70:777-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marshall, N. F., J. Peng, Z. Xie, and D. H. Price. 1996. Control of RNA polymerase II elongation potential by a novel carboxyl-terminal domain kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:27176-27183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinlivan, E. B., E. A. Holley-Guthrie, M. Norris, D. Gutsch, S. L. Bachenheimer, and S. C. Kenney. 1993. Direct BRLF1 binding is required for cooperative BZLF1/BRLF1 activation of the Epstein-Barr virus early promoter, BMRF1. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:1999-2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ragoczy, T., L. Heston, and G. Miller. 1998. The Epstein-Barr virus Rta protein activates lytic cycle genes and can disrupt latency in B lymphocytes. J. Virol. 72:7978-7984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ragoczy, T., and G. Miller. 1999. Role of the Epstein-Barr virus Rta protein in activation of distinct classes of viral lytic cycle genes. J. Virol. 73:9858-9866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rickinson, A. B., S. Finerty, and M. A. Epstein. 1978. Inhibition by phosphonoacetate of the in vitro outgrowth of Epstein-Barr virus genome-containing cell lines from the blood of infectious mononucleosis patients. IARC Sci. Publ. 1978:721-728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rooney, C., N. Taylor, J. Countryman, H. Jenson, J. Kolman, and G. Miller. 1988. Genome rearrangements activate the Epstein-Barr virus gene whose product disrupts latency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:9801-9805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato, H., H. Takeshita, M. Furukawa, and M. Seiki. 1992. Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 transactivator is a negative regulator of Jun. J. Virol. 66:4732-4736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Savard, M., C. Belanger, M. Tardif, P. Gourde, L. Flamand, and J. Gosselin. 2000. Infection of primary human monocytes by Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 74:2612-2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schepers, A., D. Pich, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1993. A transcription factor with homology to the AP-1 family links RNA transcription and DNA replication in the lytic cycle of Epstein-Barr virus. EMBO J. 12:3921-3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schepers, A., D. Pich, J. Mankertz, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1993. cis-acting elements in the lytic origin of DNA replication of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 67:4237-4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Serio, T. R., A. Angeloni, J. L. Kolman, L. Gradoville, R. Sun, D. A. Katz, W. Van Grunsven, J. Middeldorp, and G. Miller. 1996. Two 21-kilodalton components of the Epstein-Barr virus capsid antigen complex and their relationship to ZEBRA-associated protein p21 (ZAP21). J. Virol. 70:8047-8054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Serio, T. R., J. L. Kolman, and G. Miller. 1997. Late gene expression from the Epstein-Barr virus BcLF1 and BFRF3 promoters does not require DNA replication in cis. J. Virol. 71:8726-8734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shibata, D., and L. M. Weiss. 1992. Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 140:769-774. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sinclair, A. J., M. Brimmell, F. Shanahan, and P. J. Farrell. 1991. Pathways of activation of the Epstein-Barr virus productive cycle. J. Virol. 65:2237-2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sista, N. D., C. Barry, K. Sampson, and J. Pagano. 1995. Physical and functional interaction of the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 transactivator with the retinoic acid receptors RAR alpha and RXR alpha. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:1729-1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Summers, W. C., and G. Klein. 1976. Inhibition of Epstein-Barr virus DNA synthesis and late gene expression by phosphonoacetic acid. J. Virol. 18:151-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takada, K., and Y. Ono. 1989. Synchronous and sequential activation of latently infected Epstein-Barr virus genomes. J. Virol. 63:445-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takada, K., N. Shimizu, S. Sakuma, and Y. Ono. 1986. trans activation of the latent Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) genome after transfection of the EBV DNA fragment. J. Virol. 57:1016-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taylor, N., J. Countryman, C. Rooney, D. Katz, and G. Miller. 1989. Expression of the BZLF1 latency-disrupting gene differs in standard and defective Epstein-Barr viruses. J. Virol. 63:1721-1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taylor, N., E. Flemington, J. L. Kolman, R. P. Baumann, S. H. Speck, and G. Miller. 1991. ZEBRA and a Fos-GCN4 chimeric protein differ in their DNA-binding specificities for sites in the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 promoter. J. Virol. 65:4033-4041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Urier, G., M. Buisson, P. Chambard, and A. Sergeant. 1989. The Epstein-Barr virus early protein EB1 activates transcription from different responsive elements including AP-1 binding sites. EMBO J. 8:1447-1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wada, T., T. Takagi, Y. Yamaguchi, H. Kawase, M. Hiramoto, A. Ferdous, M. Takayama, K. A. Lee, H. C. Hurst, and H. Handa. 1996. Copurification of casein kinase II with transcription factor ATF/E4TF3. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:876-884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weiss, L. M., J. G. Strickler, R. A. Warnke, D. T. Purtilo, and J. Sklar. 1987. Epstein-Barr viral DNA in tissues of Hodgkin's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 129:86-91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wolf, H., H. zur Hausen, and V. Becker. 1973. EB viral genomes in epithelial nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Nat. New Biol. 244:245-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamaguchi, Y., T. Wada, F. Suzuki, T. Takagi, J. Hasegawa, and H. Handa. 1998. Casein kinase II interacts with the bZIP domains of several transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:3854-3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yankulov, K., J. Blau, T. Purton, S. Roberts, and D. L. Bentley. 1994. Transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II is stimulated by transactivators. Cell 77:749-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zerby, D., C.-J. Chen, E. Poon, D. Lee, R. Shiekhattar, and P. M. Lieberman. 1999. The amino-terminal C/H1 domain of CREB binding protein mediates Zta transcriptional activation of latent Epstein-Barr virus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1617-1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang, Q., D. Gutsch, and S. Kenney. 1994. Functional and physical interaction between p53 and BZLF1: implications for Epstein-Barr virus latency. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:1929-1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang, Q., Y. Hong, D. Dorsky, E. Holley-Guthrie, S. Zalani, N. A. Elshiekh, A. Kiehl, T. Le, and S. Kenney. 1996. Functional and physical interactions between the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) proteins BZLF1 and BMRF1: effects on EBV transcription and lytic replication. J. Virol. 70:5131-5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou, M., M. A. Halanski, M. F. Radonovich, F. Kashanchi, J. Peng, D. H. Price, and J. N. Brady. 2000. Tat modifies the activity of CDK9 to phosphorylate serine 5 of the RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:5077-5086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]