Abstract

T-helper responses are important for controlling chronic viral infections, yet T-helper responses specific to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), particularly to envelope glycoproteins, are lacking in the vast majority of HIV-infected individuals. It was previously shown that the presence of antibodies to the CD4-binding domain (CD4bd) of HIV-1 glycoprotein 120 (gp120) prevents T-helper responses to gp120, but their suppressive mechanisms were undefined (C. E. Hioe et al., J. Virol. 75:10950-10957, 2001). The present study demonstrates that gp120, when complexed to anti-CD4bd antibodies, becomes more resistant to proteolysis by lysosomal enzymes from antigen-presenting cells such that peptide epitopes are not released and presented efficiently by major histocompatibility complex class II molecules to gp120-specific CD4 T cells. Antibodies to other gp120 regions do not confer this effect. Thus, HIV may evade anti-viral T-helper responses by inducing and exploiting antibodies that conceal the virus envelope antigens from T cells.

T-helper (Th) cells are considered critical for controlling chronic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection (34), yet HIV-1-specific Th responses, particularly to the virus envelope, are lacking in most HIV-1-infected individuals (33). Even among the exceptional long-term nonprogressors who exhibit vigorous virus-specific lymphoproliferation, the CD4 T-cell responses are usually directed to the gag or other internal virus antigens, while Th responses to the envelope glycoproteins are much poorer or undetectable (33). Because the envelope glycoproteins are the critical target antigens for antibody (Ab)-mediated neutralization of the virus (44), the absence of envelope-specific Th responses in HIV-infected patients could seriously diminish the capacity of patients to elicit and maintain virus-neutralizing Ab responses, especially in the face of the continuous emergence of variant viruses during chronic HIV-1 infection. Indeed, using the murine model of chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection, Ciurea et al. (5) provide evidence that the lack of CD4 T-cell responses during persistent virus infection leads to the failure of infected hosts to elicit effective Ab responses against emerging neutralization-escape mutants.

Multiple factors may contribute to the poor envelope-specific Th responses in HIV-infected patients, such as preferential infection and consequent destruction or dysfunction of HIV-1-specific CD4 T cells by the virus (9), rich glycosylation of the envelope glycoproteins which interferes with the processing and generation of T-cell epitopes (1, 36, 40), and high mutation rates of the envelope gene allowing rapid emergence of escape or antagonistic mutations (10, 25). Earlier studies identified a novel factor contributing to the abrogation of glycoprotein 120 (gp120)-specific CD4 T-cell responses, namely, Abs to the CD4-binding domain (CD4bd) of gp120 (17, 18). In the presence of these Abs, CD4 T-cell responses to various gp120 epitopes, including those distant from the CD4bd, are prevented. The inhibitory activity was observed in vitro with human anti-CD4bd monoclonal Abs (MAbs) as well as with polyclonal serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) from chronically HIV-1-infected patients who produce anti-CD4bd Abs. Importantly, Abs to other gp120 regions do not exhibit this activity. Although the effect of anti-CD4bd Abs in vivo has not been fully explored, recent findings show a significant correlation between the lack of these inhibitory Abs and the presence of envelope-specific lymphoproliferation in a few exceptional HIV-1-infected patients and a correlation with a delay or absence of disease progression (2, 3), implicating these Abs in undermining anti-HIV-1 immunity and promoting virus-mediated pathogenesis.

The exact mechanisms by which anti-CD4bd Abs prevent CD4 T-cell responses to gp120 have not been defined, although data from previous studies rule out a number of possibilities. These Abs do not affect the CD4 T cell directly and do not alter the overall functions of the antigen-presenting cells (APCs), as evidenced by the fact that T-cell responses to other antigens of HIV-1, mycobacteria, and cytomegalovirus are not diminished in the presence of anti-CD4bd Abs (17, 18). Notably, formation of the gp120/anti-CD4bd Ab complexes is essential for the inhibitory activity, and the complexes must be present during antigen pulsing of APCs (18), indicating that these Abs, when forming complexes with gp120, affect gp120 antigen uptake or processing by APCs for subsequent major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II presentation to cognate CD4 T cells. The capacity of Abs to alter antigen processing has been well documented in the literature. Earlier studies with model antigens, such as β-galactosidase, cytochrome c, and tetanus toxoid demonstrated that Abs can affect the conformation and stability of antigens (28) and protect antigenic sites from proteolytic digestion (8, 20), resulting in abrogation of T-cell responses to certain epitopes while causing enhancement or no effect on the responses to other epitopes (26, 39, 43). Corradin and Engers (7) also showed that the proliferation of T-cell clones specific for apo-cytochrome c is blocked by a MAb directed to that particular antigen. In the case of HIV-1 gp120, the binding of Abs to the receptor-binding sites has been reported to induce substantial conformational rearrangement of the gp120 core structure, accompanied by unusually large thermodynamic changes that render the gp120 molecule more rigid and resistant to degradative enzymes, such as endoglycosidase H (24).

The present study examines whether anti-CD4bd Abs affect gp120-specific CD4 T-cell responses by interfering with gp120 proteolytic processing necessary for MHC class II antigen presentation to CD4 T cells. An in vitro proteolysis assay was developed to compare quantitatively and qualitatively the proteolytic digestion of gp120 complexed with anti-CD4bd MAbs with that of uncomplexed gp120 or gp120 bound by other anti-gp120 MAbs. We also evaluated the proteolytic digestion of gp120 pretreated with serum IgG from HIV-positive patients with different anti-CD4bd Ab titers. This study describes a novel HIV immune evasion mechanism by which virus-specific Abs generated during infection undermine the T-cell immunity necessary to help control the infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HIV envelope antigens.

Recombinant low-endotoxin-grade HIV-1 gp120IIIB and gp120JRFL (Progenics) were obtained commercially and as a generous gift through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH). Recombinant endotoxin-free HIV-1 gp120 of subtype C primary isolate 93MW959 (GenBank no. U08453) (11) and subtype B primary isolate TH14-12 (GenBank no. U08801) (11) were produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells and purified as described previously (4, 29).

The synthetic peptide (206PKISFEPIPIHYCAPAGFAI225) representing the T-cell epitope in the C2 domain of HIV-1 gp120MN was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH.

Aldrithiol-2 (AT-2)-inactivated IIIB virions grown in CEMx174(T1) cells were a gift of Jeffrey Lifson (SAIC Frederick, National Cancer Institute) (35). The highly purified virus stock contained 2.85 μg of gp120 ml−1 and 200 μg of p24 ml−1.

Abs.

Human MAbs were gifts of Susan Zolla-Pazner (New York University [NYU] School of Medicine). Human MAbs 450-D and 670-D are specific for the C5 region of gp120 (21, 46), MAbs 559/64-D and 654-D recognize the CD4-binding domain (21, 27), MAb 694/98-D recognizes an epitope in the V3 loop (14, 16), and MAb 697-D recognizes the V2 loop (15). MAb 860-55D, which recognizes the parvovirus B19 VP2 antigen (12), was used as a negative control.

Serum IgG from six chronically HIV-infected individuals and an HIV-negative control were purified on protein G columns (Amersham Biosciences), and anti-CD4bd Ab titers were determined using a previously described enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (3). Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired t test (GraphPad Prism).

T-cell lines.

HIV-1 gp120-specific CD4 T-cell lines PS02 and PS04 were generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of chronically infected HIV-1 patients following multiple rounds of in vitro stimulation with gp120IIIB for PS02 (6) or gp120 from HIV-1 isolate 93MW959 for PS04. The PS02 line recognizes one dominant epitope located in the C2 domain (206PKISFEPIPIHYCAPAGFAI225) and a subdominant epitope in the C1 domain (92NFNMWKNNMVEQMHEDIISL111); this line is reactive to gp120 from HIV-1 isolates IIIB, JR-FL, and TH14-12. The epitopes recognized by PS04 have not been identified. Autologous Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cell lines were used as APCs in the T-cell proliferation assays and as a source of lysosomal enzymes.

Lysosomal fraction preparation.

Lysosomal fractions were prepared from B lymphoblastoid cell lines according to the published protocol (38). Briefly, 400 to 600 million B-lymphoblastoid cells were suspended in 5 ml of fractionation buffer (10 mM Trizma Base, acetic acid [pH 7], 250 mM sucrose) and homogenized with a 5-ml Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer with a 60-μm gap. Cell lysate was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 2 min and at 4,000 × g for 2 min to remove the cell debris, plasma membrane, and nucleus. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 2 min to pellet the mitochondria, endosomes, and lysosomes. The lysosomes were hypotonically lysed with 0.5 ml of distilled deionized H2O for 10 min, while the endosomes and mitochondria were removed by another ultracentrifugation step. Each lysosomal preparation was verified for the presence of cathepsin D as assessed in Western blot with an anti-cathepsin D Ab (Accurate Chemical). The lysosomal fraction was kept frozen at −20°C until use.

Proteolysis assay.

Immune complexes were formed with gp120 and anti-gp120 MAbs at a molar MAb/antigen ratio of 2 to 1 or with gp120 and purified serum IgG at a molar IgG/antigen ratio of 80 to 1 for 2 to 3 h at 37°C, and they were subsequently incubated with a mixture of purified human cathepsins B, D, and L (Sigma) (0.2 to 0.4 U ml−1 each) or with the lysosomal fraction (8.3 million cell equivalents per μg of gp120) overnight at 37°C in 0.08 M sodium acetate buffer at pH 5. The digestion products were analyzed on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels in either nonreducing or reducing (with 100 mM dithiothreitol) conditions, followed by Coomassie staining (37) or Western blot analysis. Gp120 and its fragments were detected with sheep or goat anti-gp120 antiserum (obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH) followed by human serum protein-adsorbed alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rabbit anti-sheep IgG (Zymed) or anti-goat IgG (Sigma) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate-nitroblue tetrazolium substrate (KPL).

T-cell proliferation assay.

T-cell-proliferative responses to recombinant gp120 and AT-2-inactivated virions were assessed by [3H]thymidine uptake as previously described (3, 17, 18). Briefly, recombinant gp120 or diluted AT-2-inactivated virions were incubated alone or with Abs at the designated concentrations for 3 h at 37°C. The autologous B-lymphoblastoid cells (105 cells per well) that had been mitomycin C-treated (0.1 mg ml−1) and irradiated (9,000 rads) were added and allowed to process the antigens overnight. T-cell lines (2 × 104 cells per well) were subsequently added and incubated for 2 days. T cells were then pulsed with [3H]thymidine (Perkin Elmer) for 16 to 20 h and harvested.

To assess the T-cell response to the gp120 epitopes released following in vitro proteolysis, B-lymphoblastoid cells were first treated with 0.1 mM chloroquine for 5 min at 37°C and then with 0.5% paraformaldehyde for 5 min at room temperature to prevent endocytosis and antigen processing. These fixed APCs were then used in the [3H]thymidine uptake assay as described above.

RESULTS

The presence of anti-CD4bd MAbs diminished T-cell-proliferative responses to gp120 of different HIV-1 isolates.

Anti-CD4bd MAbs, when forming complexes with gp120, prevent T-cell responses to the gp120 antigen (17, 18). This suppressive effect was noted previously on the responses to gp120 from T-cell line-adapted HIV-1 strains, such as IIIB, MN, and SF2, as well as gp120 from a low-passage Dutch isolate, W61D. In the present study we examined whether these Abs also affected the T-cell responses to gp120 of CCR5 (R5)-tropic or clinical isolates of HIV-1 subtypes B or non-B. Recombinant gp120 with sequences of HIV-1 JRFL, TH14-12 (subtype B), and 93MW959 (subtype C), as well as of HIV-1 IIIB, were tested. CD4 T-cell lines specific to each of these gp120 antigens were generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of HIV-infected subjects by repeated rounds of in vitro antigen stimulation (6). The presence of the human anti-CD4bd MAb 654-D reduced the T-cell proliferation to each of the gp120 antigens tested in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1). Consistent with previous findings (17), significant loss of response (>75%) was achieved when the ratio of Ab/gp120 is ≥1, indicating that the immune complex formation of the Ab and gp120 was necessary to mediate the inhibition. The inhibitory activity was also observed with other anti-CD4bd MAbs tested, but MAbs to other gp120 domains, such as anti-C5 MAbs 450-D and 670-D, did not cause any inhibition (Fig. 1 and references (17, 18).

FIG. 1.

The presence of an anti-CD4bd MAb prevented CD4 T-cell-proliferative responses to gp120 from the following HIV-1 isolates: IIIB (X4 tropic), JRFL (R5 tropic), TH14-12 (clade B primary isolate), and 93MW959 (clade C primary isolate). A fixed concentration of gp120 (8 nM) was used to form immune complexes with various concentrations of anti-CD4bd MAb 654-D (•) or anti-C5 MAbs 450-D (□) and 670-D (▵). Proliferation of CD4 T-cell lines PS02 and PS04 recognizing the different gp120 antigens was assessed by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Representative data from two or more independent experiments are shown.

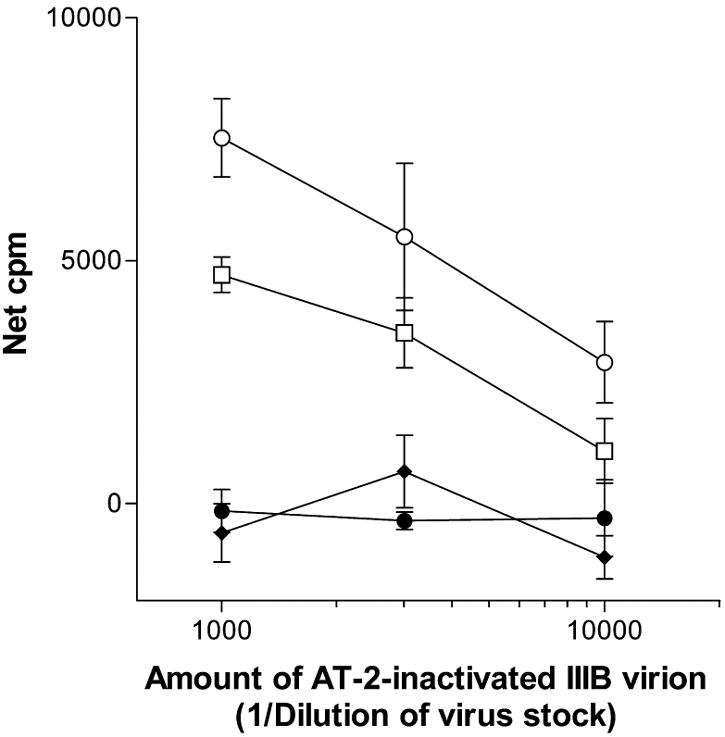

We also examined the effect of the anti-CD4bd MAbs on T-cell responses to native gp120 expressed on HIV-1 virions. The proliferation of a gp120-specific CD4 T-cell line was measured in response to purified AT-2-inactivated HIV-1 IIIB virions in the presence of the human anti-CD4bd MAb 559/64-D or 654-D, anti-C5 MAb 450-D, or no MAb. In these experiments, the MAbs were used at a constant concentration of 10 μg ml−1, which was in vast excess relative to the amounts of gp120 present in the diluted virion samples (2.85 to 0.285 ng ml−1). However, because the exact amounts of gp120 trimers expressed on the virion surface and the stoichiometry for the interaction of anti-CD4bd Abs with trimeric gp120 are not known, various dilutions of the inactivated IIIB virions were examined. Similar to the results obtained with recombinant gp120, the anti-CD4bd MAbs (559/64-D and 654-D) completely prevented T-cell proliferation, whereas the anti-C5 MAb 450-D did not (Fig. 2). The results of these experiments clearly showed that the anti-CD4bd Abs exerted a suppressive effect on T-cell responses to recombinant gp120 of R5- and CXCR4 (X4)-tropic isolates from different HIV-1 subtypes as well as to native, virion-associated gp120.

FIG. 2.

The proliferative response of CD4 T-cell lines to native gp120 expressed by HIV-1 IIIB virions was prevented by the anti-CD4bd MAbs but not by the anti-C5 MAb. Proliferation of gp120-specific CD4 T-cell line PS02 was examined in response to AT2-inactivated IIIB treated with no MAb (○), anti-CD4bd MAb 559/64-D (⧫) or 654-D (•), or anti-C5 MAb 450-D (□). The stock of AT2-inactivated IIIB virions contained 2.85 μg of gp120 ml−1 and was tested at 1:1,000, 1:3,000, and 1:10,000 dilutions, while each of the MAbs was used at a fixed concentration of 10 μg ml−1. Net counts per million were calculated by subtraction of background (5,031 cpm for T cells incubated with APCs in medium alone without immune complexes). Representative data from two independent experiments are shown.

The binding of anti-CD4bd MAbs to gp120 increased the resistance of gp120 to proteolysis by lysosomal enzymes.

Data from previous studies suggest that anti-CD4bd MAbs prevent T-cell responses to gp120 by interfering with gp120 antigen presentation. However, the steps in the MHC class II antigen processing and presentation pathway affected by these Abs have not been determined. A recent report by Kwong et al. demonstrates that the binding of gp120 by most anti-CD4bd MAbs induces unusually large thermodynamic changes in the gp120 core structure, resulting in an increased resistance of gp120 to a deglycosylating enzyme (24). This resistance to deglycosylation and potentially to proteolytic or other degradative enzymes is associated with the alteration of gp120 structural conformation or folding induced by the anti-CD4bd MAbs. Hence, in this study we examined whether the binding of anti-CD4bd MAbs would render the gp120 molecule more resistant to proteolytic digestion by a combination of cathepsins B, D, and L; these cathepsins represent some of the abundant lysosomal proteases in APCs involved in MHC class II antigen processing (19, 42).

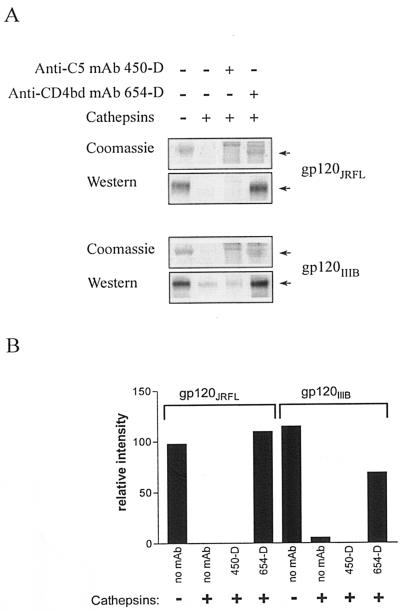

To this end, an in vitro proteolysis assay was set up in which gp120 alone or gp120 complexed with the anti-CD4bd MAb 654-D or the anti-C5 MAb 450-D was incubated for 18 to 24 h at 37°C with a mixture of purified cathepsins B, D, and L at pH 5. The degree of gp120 proteolytic digestion was determined by assessing the amounts of intact gp120 remaining as detected in the SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gel by Coomassie blue staining and by Western Blot. gp120 complexed with the anti-CD4bd MAb 654-D was not efficiently digested compared to uncomplexed gp120 or gp120 complexed to the anti-C5 MAb 450-D (Fig. 3A). This pattern was observed with gp120 from both the JRFL and IIIB strains. The relative intensity of the 120-kDa bands was calculated from the densitometry of the Coomassie blue-stained gel (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

The binding of anti-CD4bd MAb, but not anti-C5 MAb, rendered HIV-1 gp120 more resistant to proteolysis by cathepsins. (A) Recombinant gp120 of JRFL and IIIB strains was digested by a mixture of cathepsins B, D, and L after preincubation with anti-CD4bd MAb 654-D, anti-C5 MAb 450-D, or no MAb. The amounts of gp120 remaining after proteolysis were analyzed under nonreducing conditions in SDS-PAGE and were visualized by both Coomassie blue stain and Western blot staining with sheep anti-gp120 serum. (B) The relative amounts of gp120 remaining after digestion were quantitated from the Coomassie blue-stained gel by densitometry with the 1D Image Analysis Software (Scientific Imaging Systems Eastman Kodak Company). Representative data from two independent experiments are shown.

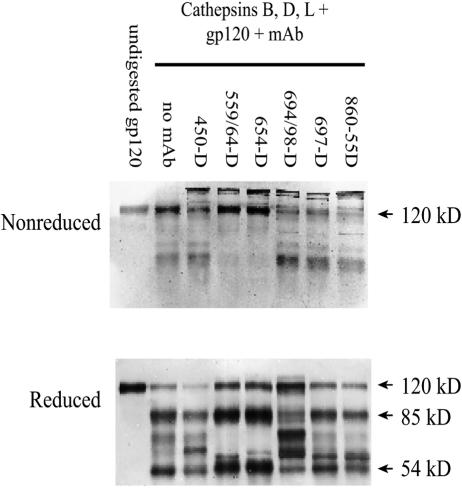

We subsequently compared fragmentation patterns of the different gp120/Ab complexes and uncomplexed gp120 after digestion with cathepsins B, D, and L. Western blot analyses with sheep or goat polyclonal anti-gp120 Abs were used to detect gp120-specific bands. Consistent with the data shown in Fig. 3A, after the cathepsin digestion, most if not all of gp120 bound by the anti-CD4bd MAbs 654-D or 559/64-D appeared to remain intact under nonreducing conditions (Fig. 4). Only when analyzed under reducing conditions does it become evident that digestion of gp120/anti-CD4bd Ab complexes cleaved the gp120 molecule, albeit producing only two prominent bands of 85 and 54 kDa. In contrast, gp120 alone or gp120 complexed with anti-C5 MAb 450-D, anti-V3 MAb 694/98-D, anti-V2 MAb 697-D, or incubated with an irrelevant MAb (anti-parvovirus MAb 860-55D) was cleaved into more fragments of diverse molecular sizes. It should also be noted that the cathepsin digestion of each of the gp120/MAb complexes resulted in a unique fragmentation pattern, which was dependent on the fine specificity of the anti-gp120 MAbs used to form the immune complexes. Taken together, these data indicate that the proteolytic digestion of gp120 complexed with anti-CD4bd MAbs resulted in distinct and more limited fragmentation than that of uncomplexed gp120 or gp120 bound by other anti-gp120 MAbs.

FIG. 4.

The fragmentation patterns of gp120 and gp120 complexed with anti-gp120 MAbs after proteolytic digestion by a mixture of cathepsins B, D, and L. Recombinant gp120IIIB was preincubated with no MAb, anti-C5 MAb 450-D, anti-CD4bd MAb 559/64-D or 654-D, anti-V3 MAb 694/98-D, anti-V2 MAb 697-D, or an irrelevant anti-parvovirus MAb 860-55D and was digested with the cathepsins. gp120 treated with no MAb and no enzymes (undigested) was also analyzed for comparison. The reaction products were run on SDS-PAGE under nonreducing or reducing conditions and were stained after Western blotting with sheep anti-gp120 serum. Representative blots of two independent experiments are shown.

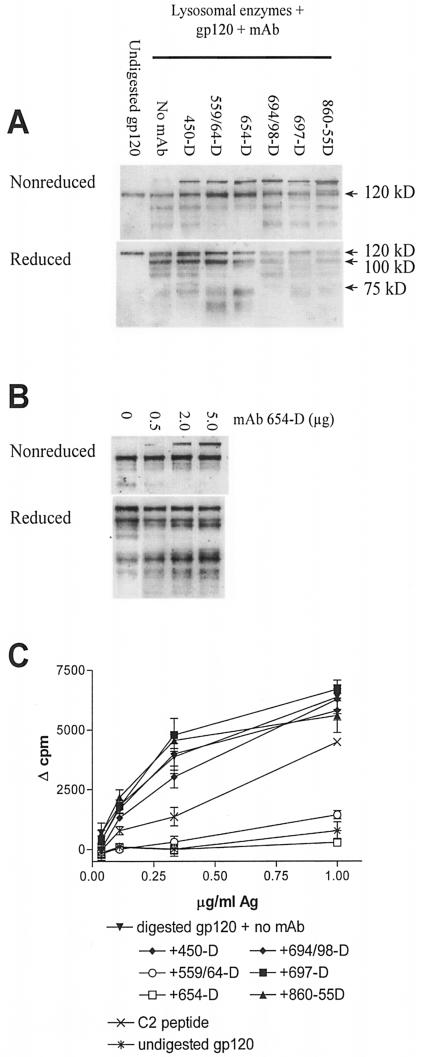

Proteolytic digestion of gp120/anti-CD4bd Ab complexes by lysosomal enzymes failed to release peptide epitopes recognized by gp120-specific CD4 T cells. APCs most likely express and utilize a larger set of tissue-specific endosomal or lysosomal proteases for antigen processing than the particular purified cathepsins we examined (31). Hence, we examined the fragmentation of gp120 and gp120 complexed with the different anti-gp120 MAbs following digestion by lysosomal enzymes isolated from the EBV-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cells that we routinely used as APCs to induce proliferation of our gp120-specific CD4 T-cell lines. Similar to the digestion patterns observed with the purified cathepsins (Fig. 4), gp120 complexed with anti-CD4bd MAbs 654-D or 559/64-D also appeared to be less efficiently digested by lysosomal enzymes than gp120 alone or gp120 complexed with the other MAbs tested (Fig. 5A). A limited fragmentation of the gp120 molecules, with a distinct pattern, was apparent when the digestion products of gp120/anti-CD4bd Ab complexes were analyzed under reducing conditions (Fig. 5A). Notably, fragments with molecular sizes ranging from 75 to 100 kDa seen in digestion products of uncomplexed gp120 and gp120 bound by other anti-gp120 MAbs were not generated efficiently upon the digestion of gp120/anti-CD4bd Ab complexes. These differences remained apparent when the digestion time was increased from overnight up to 51 h (data not shown). However, in agreement with the T-cell proliferation data, the extent of digestion was dependent on the ratio of MAb to gp120; at a MAb/gp120 ratio of 1:2, the digestion of the gp120/654D complex resembled more that of uncomplexed gp120, while at MAb/gp120 ratios of 2:1 or 5:1 in which the antibody is in excess, the digestion was significantly altered (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

(A) Proteolysis of gp120 and gp120/MAb complexes by lysosomal enzymes. Recombinant gp120IIIB was either left untreated or were treated with MAb to C5 (450-D), CD4bd (559/64-D or 654-D), V3 (694/98-D), V2 (697-D), or parvovirus (860-55D) and were then digested with lysosomal enzymes extracted from EBV-transformed B cells. The reaction products were run on SDS-PAGE under nonreducing or reducing conditions and were stained after Western blotting with sheep anti-gp120 serum. Representative blots of at least five repeated experiments are shown. (B) Resistance of recombinant gp120IIIB to lysosomal enzyme digestion was dependent on the amount of anti-CD4bd MAbs. gp120IIIB (1 μg) was treated with various amounts of anti-CD4bd MAb 654-D and was digested with lysosomal enzymes. The reaction products were analyzed by Western blot as described above. (C) The release of T-cell epitopes from digested gp120 or gp120/MAb complexes was also examined by measuring the proliferative response of the gp120-specific CD4 T-cell line PS02 to fixed autologous EBV-transformed B cells pretreated with the digestion products and used as APCs. The responses of the T cells to APCs pulsed with a C2 peptide representing the T-cell epitope and with undigested gp120 were also measured for control. Representative data of two independent T-cell assays are shown.

While the Western blot analyses demonstrated a striking alteration in the proteolysis of gp120/anti-CD4bd Ab complexes, these analyses did not allow the detection of the relatively small and specific gp120 peptide fragments that are recognized by the gp120-specific CD4 T cells. To address this issue, the digestion products were used to pulse fixed B-lymphoblastoid cells, and these cells were evaluated for their ability to stimulate the proliferation of an autologous gp120-specific CD4 T-cell line. For a positive control, fixed APCs were treated with a synthetic gp120 peptide (206PKISFEPIPIHYCAPAGFAI225) encompassing a dominant epitope in the C2 domain recognized by T-cell line PS02 (Fig. 5C). As anticipated, fixed APCs treated with intact undigested gp120 induced a very poor response, indicating the requirement of gp120 antigen processing for efficient presentation to these CD4 T cells. Also as expected, the T-cells responded vigorously to fixed APCs treated with lysosomal enzyme-digested gp120. However, the APCs treated with digestion products of gp120/anti-CD4bd Ab complexes stimulated T-cell proliferation poorly compared to the cells treated with digested gp120 or with digestion products of the other gp120/Ab complexes. Altogether, these results indicate that, when bound by anti-CD4bd Abs, gp120 became more resistant to enzymatic degradation by proteases present in the lysosomes of APCs. Consequently, proteolytic digestion of the gp120/anti-CD4bd Ab complexes, unlike digestion of the other gp120/Ab complexes, did not generate gp120 peptides that can be presented by MHC class II molecules to the CD4 T cells. Hence, T-cell responses to gp120 were not stimulated in the presence of anti-CD4bd Abs.

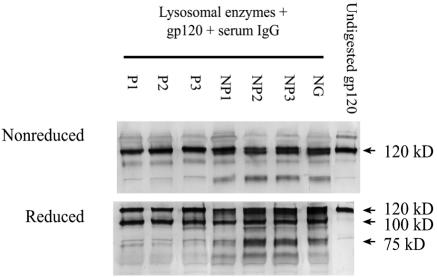

Gp120 treated with HIV-positive serum IgG containing high levels of anti-CD4bd Abs was more resistant to proteolytic degradation by lysosomal enzymes than uncomplexed gp120 or gp120 treated with serum IgG with low levels of anti-CD4bd Abs. We next sought to determine whether, similar to the anti-CD4bd MAbs, polyclonal Abs from HIV-positive subjects also affect proteolytic degradation of gp120 by lysosomal enzymes. IgG was purified from sera of three HIV-1-positive progressors who either succumbed to AIDS or required antiretroviral therapy (P1, P2, and P3) and from sera of three HIV-positive long-term nonprogressors who showed no clinical signs of AIDS after more than 10 years of infection without antiretroviral drugs (NP1, NP2, and NP3). The progressors have high titers of anti-CD4bd Abs (50% inhibitory dose [ID50] of 16,700 to 31,500), whereas the nonprogressors have undetectable levels of these Abs (ID50 of <125) (P < 0.005; Table 1). These titers are consistent with previous data showing that anti-CD4bd Ab titers of HIV-1-positive rapid or slow progressors are significantly higher than in those of long-term nonprogressors (2, 3).

TABLE 1.

Serum anti-CD4bd Ab titers and T-cell responses to gp120 in the presence of serum IgG of HIV-positive progressors and nonprogressors

| Serum IgG sample | Anti-CD4bd Ab ID50 titer | Effect of IgG on T-cell response to gp120 (% control) |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 31,500 | 9 |

| P2 | 24,200 | 32 |

| P3 | 16,700 | 49 |

| NP1 | <125 | 83 |

| NP2 | <125 | 105 |

| NP3 | <125 | 93 |

| NG | <125 | 100 |

gp120 alone or gp120 mixed with serum IgG was incubated for 18 to 24 h at 37°C with lysosomal enzymes and was analyzed by Western blot as described above. gp120 incubated with IgG from the three HIV-positive progressors was more resistant to degradation, whereas gp120 treated with IgG from the three HIV-positive nonprogressors or from an HIV-negative subject was more readily degraded to generate gp120 fragments of 75 kDa and lower (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Proteolysis of gp120 and gp120 treated with HIV-positive IgG by lysosomal enzymes. Recombinant gp120IIIB was mixed with serum IgG from HIV-positive progressors (P1, P2, and P3), nonprogressors (NP1, NP2, and NP3), or an HIV-negative subject (NG) and then was digested with lysosomal enzymes extracted from EBV-transformed B cells. The reaction products were run on SDS-PAGE under nonreducing and reducing conditions and were stained after Western blotting with an anti-gp120 MAb. A representative blot of at least two independent experiments is shown.

The effect of serum IgG from HIV-positive individuals with high serum anti-CD4bd Ab titers on gp120 proteolysis was also consistent with the diminished gp120 presentation to CD4 T cells. Hence, in the presence of IgG from the progressors, T-cell-proliferative response to gp120 was reduced to 9 to 49% and was significantly different from the response to gp120 in the presence of IgG from nonprogressors (P = 0.0085) (Table 1). IgG from nonprogressors, similar to the HIV-negative IgG control, did not affect T-cell proliferation (>83%). Although only a limited number of samples were tested here, the data clearly demonstrated an association between the levels of anti-CD4bd Abs in serum of HIV-positive subjects and the capacity of these serum Abs to block gp120 proteolysis and therefore to block the subsequent presentation of gp120 epitopes to specific CD4 T cells.

DISCUSSION

HIV-1 gp120 antigens complexed with anti-CD4bd MAbs fail to elicit gp120-specific CD4 T-cell-proliferative responses, while MAbs to other gp120 domains do not exhibit this activity. This phenomenon is observed with recombinant gp120 antigens from X4- and R5-tropic HIV-1 isolates of B or non-B subtypes as well as with native gp120 associated with HIV-1 virions. Previous studies have also demonstrated that the effect of anti-CD4bd Abs has widespread effects, eliminating the responses of different CD4 T-cell lines specific for epitopes located in various gp120 regions, such as C1, C2, V2, and V3 (17). The present study aimed to define the underlying mechanisms by which anti-CD4bd Abs affect T-cell responses to gp120.

Abs are known to modulate T-cell responses to the specific antigens by facilitating antigen uptake via Fc receptors and by protecting epitopes from proteolytic processing in the APCs. This has been documented with model antigens, such as tetanus toxoid and β-galactosidase (26, 43). In this study, we provide the first evidence that Abs produced during HIV infection, specifically anti-CD4bd Abs, have the capacity to disturb the proteolytic processing of exogenous gp120 antigens by lysosomal enzymes from APCs, such that gp120 peptides are not efficiently released and presented to Th cells by MHC class II molecules. However, unlike Abs specific for tetanus toxoid, apo-cytochrome c, or β-galactosidase, which affect the processing of only certain epitopes directly contacted by the respective Abs, anti-CD4bd Abs appear to globally affect the proteolysis of the entire gp120 protein. Figure 4 clearly shows that after proteolytic digestion of gp120 and anti-CD4bd Ab complexes, gp120 molecules are cleaved only to produce a limited set of prominent fragments of >50 kDa, which with intact disulfide bonds comprise part of the 120-kDa molecules remaining after enzymatic treatment. More importantly, the digestion of these complexes fails to release a T-cell epitope in the C2 domain of gp120, even though this C2 region is not part of the Ab binding site in the CD4-binding domain. Hence, it is unlikely that the protection of the T-cell epitope is due to direct shielding of specific T-cell epitopes by the anti-CD4bd Abs. Rather, we surmise that the capacity of anti-CD4bd Abs to increase resistance of gp120 to proteolysis is likely due to the induction of substantial rearrangement or folding of the inner and outer domains of the gp120 core, which Myszka et al. and Kwong et al. have demonstrated to bear an unusually large entropic penalty (24, 30). Indeed, these thermodynamic changes seem to make the gp120 molecule a more rigid and resistant substrate for degradative enzymes, including endoglycosidase H, and as shown here, cathepsins. Such changes would broadly affect the proteolysis of gp120 regardless of the cleavage sites in the gp120 protein. This mechanism is consistent with previous findings that the anti-CD4bd Abs affect T-cell responses to epitopes in the C1, C2, and V3 regions of gp120, which are not directly involved in CD4-binding. Moreover, this mechanism provides a clear explanation as to why anti-CD4bd Abs specifically affect gp120 responses but have no effect on the responses to HIV-1 p24 and antigens of mycobacteria and cytomegalovirus (17, 18).

Another explanation for the failure of gp120-specific T cells to respond to gp120 in the presence of anti-CD4bd Abs is induction of apoptosis or anergy of gp120-specific T cells by gp120/anti-CD4bd Ab complexes, but this mechanism is rather unlikely because previous studies showed that the gp120/anti-CD4bd Ab complexes did not affect the proliferation of gp120-specific T-cell lines to their specific peptide epitopes (18). Nevertheless, the effects of these immune complexes on gp120-specific CD4 T cells in vivo remain to be determined.

In addition to anti-CD4bd MAbs, polyclonal serum Abs from HIV-positive subjects also render gp120 more resistant to proteolysis. The levels of anti-CD4bd Abs in the serum are associated with the capacity to interfere with gp120 proteolytic digestion and to prevent CD4 T-cell responses to gp120. It is interesting that higher anti-CD4bd Ab titers in sera of HIV-positive patients have been associated with faster progression to AIDS, while the majority of long-term nonprogressors have undetectable levels of these particular Abs (2, 3).

Interference with steps in the antigen presentation pathways by a variety of mechanisms is a method of immune evasion described for several viruses. For example, many herpesviruses express viral proteins that interfere with antigen presentation steps in both MHC class I and class II pathways (45). Thus, human cytomegalovirus expresses a kinase that phosphorylates its immediate-early protein; the phosphorylation of this protein prevents the generation of a MHC class I-restricted immunodominant epitope (13). Interference with the MHC class II antigen presentation pathway has also been described for this virus: surface MHC class II expression is reduced by expression of the viral protein US2, which destroys HLA-DRα and DMα chains (41). Similarly, HIV proteins such as vpu and nef interfere with MHC class I antigen presentation. vpu decreases MHC class I expression, possibly by targeting nascent MHC class I heavy chains for destruction in the endoplasmic reticulum (22), while nef can remove MHC class I molecules from the cell surface and redirect them to the trans-Golgi network via the PACS-1-mediated sorting pathway (32). The present studies provide evidence that HIV can also prevent MHC class II antigen presentation by inducing anti-CD4bd Abs that retard the requisite step of proteolytic processing of the gp120 antigen.

Induction of Abs with potent virus-neutralizing activities would seem to benefit the host. However, except for one recombinant anti-CD4bd MAb, IgG1b12, all anti-CD4bd MAbs generated thus far from cells of chronically HIV-1-infected individuals do not effectively neutralize HIV-1 clinical isolates (23). Moreover, all of the anti-CD4bd MAbs tested in this and in previous studies hinder gp120-specific CD4 T-cell responses (Fig. 1 and 2 and references 17 and 18). Hence, the inhibitory rather than the protective effects of anti-CD4bd Abs may prevail during HIV-1 infection. These studies, then, reveal a novel immunopathogenic mechanism of HIV-1, in which during chronic infection the virus induces and exploits the hosts' ability to produce virus-specific Abs that are not only generally ineffective against the virus but also interfere with viral antigen presentation, weakening T-cell-mediated responses against the virus.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Merit Review Type I Award (C.E.H.), the Research Enhancement Award Program (REAP) of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the NYU Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) Immunology Core (NIH Grant AI-27742), and by NIH grant AI-48371 (C.E.H.).

We thank Susan Zolla-Pazner (NYU School of Medicine) for critical reviews and helpful discussions on this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Botarelli, P., B. A. Houlden, N. L. Haigwood, C. Servis, D. Montagna, and S. Abrignani. 1991. N-glycosylation of HIV-gp120 may constrain recognition by T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 147:3128-3132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chien, P. C., Jr., D. Chen, P. Chen, M. Tuen, S. Cohen, S. A. Migueles, M. Connors, E. Rosenberg, U. Malhotra, C. Gonzalez, and C. E. Hioe. 2004. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients with envelope-specific lymphoproliferation and long-term nonprogressors lack antibodies suppressing gp120 antigen presentation. J. Infect. Dis. 189:852-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chien, P. C., Jr., S. Cohen, C. Kleeberger, J. Giorgi, J. Phair, S. Zolla-Pazner, and C. E. Hioe. 2002. High levels of antibodies to the CD4 binding domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein 120 are associated with faster disease progression. J. Infect. Dis. 186:205-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cicala, C., J. Arthos, A. Rubbert, S. Selig, K. Wildt, O. J. Cohen, and A. S. Fauci. 2000. HIV-1 envelope induces activation of caspase-3 and cleavage of focal adhesion kinase in primary human CD4(+) T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1178-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciurea, A., L. Hunziker, P. Klenerman, H. Hengartner, and R. M. Zinkernagel. 2001. Impairment of CD4(+) T cell responses during chronic virus infection prevents neutralizing antibody responses against virus escape mutants. J. Exp. Med. 193:297-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen, S., M. Tuen, and C. E. Hioe. Propagation of CD4 T cells specific for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope gp120 from chronically HIV-1-infected subjects. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Corradin, G., and H. D. Engers. 1984. Inhibition of antigen-induced T-cell clone proliferation by antigen-specific antibodies. Nature 308:547-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson, H. W., and C. Watts. 1989. Epitope-directed processing of specific antigen by B lymphocytes. J. Cell Biol. 109:85-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douek, D. C., J. M. Brenchley, M. R. Betts, D. R. Ambrozak, B. J. Hill, Y. Okamoto, J. P. Casazza, J. Kuruppu, K. Kunstman, S. Wolinsky, Z. Grossman, M. Dybul, A. Oxenius, D. A. Price, M. Connors, and R. A. Koup. 2002. HIV preferentially infects HIV-specific CD4+ T cells. Nature 417:95-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenoglio, D., G. Li Pira, L. Lozzi, L. Bracci, D. Saverino, P. Terranova, L. Bottone, S. Lantero, A. Megiovanni, A. Merlo, and F. Manca. 2000. Natural analogue peptides of an HIV-1 GP120 T-helper epitope antagonize response of GP120-specific human CD4 T-cell clones. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 23:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao, F., L. Yue, S. Craig, C. L. Thornton, D. L. Robertson, F. E. McCutchan, J. A. Bradac, P. M. Sharp, and B. H. Hahn. 1994. Genetic variation of HIV type 1 in four World Health Organization-sponsored vaccine evaluation sites: generation of functional envelope (glycoprotein 160) clones representative of sequence subtypes A, B, C, and E. W. H. O. Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:1359-1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gigler, A., S. Dorsch, A. Hemauer, C. Williams, S. Kim, N. S. Young, S. Zolla-Pazner, H. Wolf, M. K. Gorny, and S. Modrow. 1999. Generation of neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies against parvovirus B19 proteins. J. Virol. 73:1974-1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbert, M. J., S. R. Riddell, B. Plachter, and P. D. Greenberg. 1996. Cytomegalovirus selectively blocks antigen processing and presentation of its immediate-early gene product. Nature 383:720-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorny, M. K., A. J. Conley, S. Karwowska, A. Buchbinder, J. Y. Xu, E. A. Emini, S. Koenig, and S. Zolla-Pazner. 1992. Neutralization of diverse human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants by an anti-V3 human monoclonal antibody. J. Virol. 66:7538-7542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorny, M. K., J. P. Moore, A. J. Conley, S. Karwowska, J. Sodroski, C. Williams, S. Burda, L. J. Boots, and S. Zolla-Pazner. 1994. Human anti-V2 monoclonal antibody that neutralizes primary but not laboratory isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 68:8312-8320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorny, M. K., J. Y. Xu, S. Karwowska, A. Buchbinder, and S. Zolla-Pazner. 1993. Repertoire of neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies specific for the V3 domain of HIV-1 gp120. J. Immunol. 150:635-643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hioe, C. E., G. J. Jones, A. D. Rees, S. Ratto-Kim, D. Birx, C. Munz, M. K. Gorny, M. Tuen, and S. Zolla-Pazner. 2000. Anti-CD4-binding domain antibodies complexed with HIV type 1 glycoprotein 120 inhibit CD4+ T cell-proliferative responses to glycoprotein 120. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:893-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hioe, C. E., M. Tuen, P. C. Chien, Jr., G. Jones, S. Ratto-Kim, P. J. Norris, W. J. Moretto, D. F. Nixon, M. K. Gorny, and S. Zolla-Pazner. 2001. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 presentation to CD4 T cells by antibodies specific for the CD4 binding domain of gp120. J. Virol. 75:10950-10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honey, K., and A. Y. Rudensky. 2003. Lysosomal cysteine proteases regulate antigen presentation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:472-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jemmerson, R., and Y. Paterson. 1986. Mapping epitopes on a protein antigen by the proteolysis of antigen-antibody complexes. Science 232:1001-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karwowska, S., M. K. Gorny, A. Buchbinder, V. Gianakakos, C. Williams, T. Fuerst, and S. Zolla-Pazner. 1992. Production of human monoclonal antibodies specific for conformational and linear non-V3 epitopes of gp120. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 8:1099-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerkau, T., I. Bacik, J. R. Bennink, J. W. Yewdell, T. Hunig, A. Schimpl, and U. Schubert. 1997. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) vpu protein interferes with an early step in the biosynthesis of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules. J. Exp. Med. 185:1295-1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler, J. A., Jr., P. M. McKenna, E. A. Emini, C. P. Chan, M. D. Patel, S. K. Gupta, G. E. Mark III, C. F. Barbas III, D. R. Burton, and A. J. Conley. 1997. Recombinant human monoclonal antibody IgG1b12 neutralizes diverse human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolates. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 13:575-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwong, P. D., M. L. Doyle, D. J. Casper, C. Cicala, S. A. Leavitt, S. Majeed, T. D. Steenbeke, M. Venturi, I. Chaiken, M. Fung, H. Katinger, P. W. Parren, J. Robinson, D. Van Ryk, L. Wang, D. R. Burton, E. Freire, R. Wyatt, J. Sodroski, W. A. Hendrickson, and J. Arthos. 2002. HIV-1 evades antibody-mediated neutralization through conformational masking of receptor-binding sites. Nature 420:678-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lekutis, C., and N. L. Letvin. 1998. Substitutions in a major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 epitope can affect CD4+ T-helper-cell function. J. Virol. 72:5840-5844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manca, F., D. Fenoglio, A. Kunkl, C. Cambiaggi, M. Sasso, and F. Celada. 1988. Differential activation of T cell clones stimulated by macrophages exposed to antigen complexed with monoclonal antibodies. A possible influence of paratope specificity on the mode of antigen processing. J. Immunol. 140:2893-2898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKeating, J. A., J. Bennett, S. Zolla-Pazner, M. Schutten, S. Ashelford, A. L. Brown, and P. Balfe. 1993. Resistance of a human serum-selected human immunodeficiency virus type 1 escape mutant to neutralization by CD4 binding site monoclonal antibodies is conferred by a single amino acid change in gp120. J. Virol. 67:5216-5225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melchers, F., and W. Messer. 1970. Enhanced stability against heat denaturation of E. coli wild type and mutant beta-galactosidase in the presence of specific antibodies. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 40:570-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mossman, S. P., F. Bex, P. Berglund, J. Arthos, S. P. O'Neil, D. Riley, D. H. Maul, C. Bruck, P. Momin, A. Burny, P. N. Fultz, J. I. Mullins, P. Liljestrom, and E. A. Hoover. 1996. Protection against lethal simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsmmPBj14 disease by a recombinant Semliki Forest virus gp160 vaccine and by a gp120 subunit vaccine. J. Virol. 70:1953-1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myszka, D. G., R. W. Sweet, P. Hensley, M. Brigham-Burke, P. D. Kwong, W. A. Hendrickson, R. Wyatt, J. Sodroski, and M. L. Doyle. 2000. Energetics of the HIV gp120-CD4 binding reaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:9026-9031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakagawa, T. Y., and A. Y. Rudensky. 1999. The role of lysosomal proteinases in MHC class II-mediated antigen processing and presentation. Immunol. Rev. 172:121-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piguet, V., L. Wan, C. Borel, A. Mangasarian, N. Demaurex, G. Thomas, and D. Trono. 2000. HIV-1 Nef protein binds to the cellular protein PACS-1 to downregulate class I major histocompatibility complexes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:163-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitcher, C. J., C. Quittner, D. M. Peterson, M. Connors, R. A. Koup, V. C. Maino, and L. J. Picker. 1999. HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cells are detectable in most individuals with active HIV-1 infection, but decline with prolonged viral suppression. Nat. Med. 5:518-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg, E. S., J. M. Billingsley, A. M. Caliendo, S. L. Boswell, P. E. Sax, S. A. Kalams, and B. D. Walker. 1997. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science 278:1447-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossio, J. L., M. T. Esser, K. Suryanarayana, D. K. Schneider, J. W. Bess, Jr., G. M. Vasquez, T. A. Wiltrout, E. Chertova, M. K. Grimes, Q. Sattentau, L. O. Arthur, L. E. Henderson, and J. D. Lifson. 1998. Inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity with preservation of conformational and functional integrity of virion surface proteins. J. Virol. 72:7992-8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rudd, P. M., T. Elliott, P. Cresswell, I. A. Wilson, and R. A. Dwek. 2001. Glycosylation and the immune system. Science 291:2370-2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning, a laboratory manual, 2nd ed., vol. 3. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 38.Schroter, C. J., M. Braun, J. Englert, H. Beck, H. Schmid, and H. Kalbacher. 1999. A rapid method to separate endosomes from lysosomal contents using differential centrifugation and hypotonic lysis of lysosomes. J. Immunol. Methods 227:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simitsek, P. D., D. G. Campbell, A. Lanzavecchia, N. Fairweather, and C. Watts. 1995. Modulation of antigen processing by bound antibodies can boost or suppress class II major histocompatibility complex presentation of different T cell determinants. J. Exp. Med. 181:1957-1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Surman, S., T. D. Lockey, K. S. Slobod, B. Jones, J. M. Riberdy, S. W. White, P. C. Doherty, and J. L. Hurwitz. 2001. Localization of CD4+ T cell epitope hotspots to exposed strands of HIV envelope glycoprotein suggests structural influences on antigen processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4587-4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomazin, R., J. Boname, N. R. Hegde, D. M. Lewinsohn, Y. Altschuler, T. R. Jones, P. Cresswell, J. A. Nelson, S. R. Riddell, and D. C. Johnson. 1999. Cytomegalovirus US2 destroys two components of the MHC class II pathway, preventing recognition by CD4+ T cells. Nat. Med. 5:1039-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villadangos, J. A., and H. L. Ploegh. 2000. Proteolysis in MHC class II antigen presentation: who's in charge? Immunity 12:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watts, C., and A. Lanzavecchia. 1993. Suppressive effect of antibody on processing of T cell epitopes. J. Exp. Med. 178:1459-1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss, R. A., P. R. Clapham, J. N. Weber, A. G. Dalgleish, L. A. Lasky, and P. W. Berman. 1986. Variable and conserved neutralization antigens of human immunodeficiency virus. Nature 324:572-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yewdell, J. W., and A. B. Hill. 2002. Viral interference with antigen presentation. Nat. Immunol. 3:1019-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zolla-Pazner, S., J. O'Leary, S. Burda, M. K. Gorny, M. Kim, J. Mascola, and F. McCutchan. 1995. Serotyping of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from diverse geographic locations by flow cytometry. J. Virol. 69:3807-3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]