Abstract

During the past decade, localization microscopy (LM) has transformed into an accessible, commercially available technique for life sciences. However, data processing can be challenging to the non-specialist and care is still needed to produce meaningful results. PALMsiever has been developed to provide a user-friendly means of visualizing, filtering and analyzing LM data. It includes drift correction, clustering, intelligent line profiles, many rendering algorithms and 3D data visualization. It incorporates the main analysis and data processing modalities used by experts in the field, as well as several new features we developed, and makes them broadly accessible. It can easily be extended via plugins and is provided as free of charge open-source software.

Contact: thomas.pengo@gmail.com

Eight years since its inception, single-molecule localization microscopy (LM; Betzig et al., 2006; Rust et al., 2006) has transformed from a specialist technique in the hands of a few labs, to an accessible, commercially available technique, widely used in the life sciences (Patterson et al., 2010). Although the instrumentation required for LM is now readily available, the data processing aspects of the technique remain less well developed. Most recent developments in LM data processing have focused on extracting single molecule localizations from the raw data (ISBI LM Challenge 2012, http://bigwww.epfl.ch/palm/), or visualization of processed data (Baddeley et al., 2010). However, these represent just the first and last steps of analysis. Equally important are the post-processing steps required to convert raw localizations to meaningful data. Filtering out spurious localizations, grouping and tracking of multiple localizations, correcting drift, choosing the appropriate rendering and performing statistical analysis on the localizations are just a few equally important aspects for which little software support exists (Wolter et al., 2012), leaving the non-specialist with the unnecessary burden of developing ad hoc solutions.

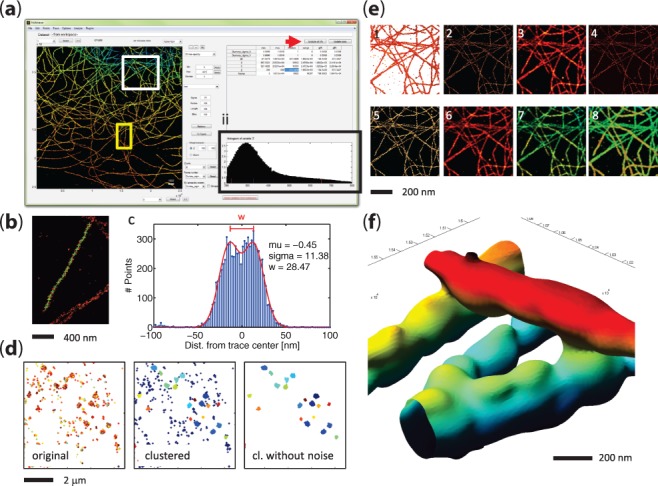

PALMsiever was made publicly available in 2012 (Pengo and Manley, 2012) to fill this void and has been under continuous development since then (ISBI LM Challenge 2012, http://bigwww.epfl.ch/palm/). While other complementary tools have since been introduced (El Beheiry and Dahan, 2013; Ovesny et al., 2014), PALMsiever provides a single user-friendly extensible platform for LM data processing, combining visualization, post-processing, filtering and analysis features. The user interface (Fig. 1a) encourages data exploration, by rendering the data on-the-fly, interactively responding to re-centering and zooming. Spurious localizations can be interactively eliminated by iteratively adjusting the display ranges for each of the available parameters, either directly by inspecting its histogram (Fig. 1ii), or automatically by removing the lower and upper 5% (Fig. 1a, arrow). Microscope drift during acquisition can be corrected using the 3D drift correction plugins, either by autocorrelation analysis or using fiducial markers. Line profiles (a simple right-click in the image) are automatically aligned to the underlying structure by principal components analysis and fitted to a Gaussian function. In the presence of curvilinear structures, the included tracing tool can automatically follow the structure (Fig. 1b) and generate a fit from the projected profile (Fig. 1c). To compensate for the presence of multiple detections of the same molecule in successive frames, PALMsiever also includes a grouping algorithm, where detections are grouped into single molecules according to spatio-temporal proximity. Cluster analysis of interacting biomolecules is enabled by a plugin for the density-based cluster analysis DBSCAN (Endesfelder et al., 2013; Ester, 1996), which also facilitates noise removal (Fig. 1d, showing clustering of GaG-mEos2 data). Many rendering methods are available such as scatterplot, 2D histogram, blurred 2D histogram, automatic kernel density estimation (Botev, 2010), Delaunay triangulation, jittered 2D histogram, hue-encoded depth and a novel occluding hue-encoded depth (Fig. 1e, in the same order). Thanks to 3D data support across the software, 3D volumes can be easily exported to a TIFF stack, visualized as a 3D isosurface (Fig. 1f), explored using slicing, or rendered using either the classical hue-based depth coding, or a novel rendering that correctly accounts for overlapping structures. As an alternative, data can also be exported for visualization with ViSP (El Beheiry and Dahan, 2013). PALMsiever has been designed with software interoperability in mind, so a number of predefined input file formats have been provided, e.g. QuickPALM (Henriques et al., 2010), RapidSTORM (Wolter et al., 2012), Leica SR GSD (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), PeakSelector (courtesy of H.Hess, HHMI), uTrack (Jaqaman et al., 2008), Vutara (Vutara, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA) and Octane (Niu and Yu, 2008). It can also easily be extended to import other file formats by adding new import filters or incorporate new analyses by writing plugins using MATLAB, and renderings can also conveniently be made available to the system clipboard or saved as TIFFs for inclusion in presentations or publications. The software is open-source and can be downloaded (together with example datasets) at http://code.google.com/p/palm-siever.

Fig. 1.

Single-molecule localization microscopy images, analyzed and rendered with PALMsiever. (a) The user interface encourages exploration of the data. The histogram (ii) of each parameter can be analyzed and automatically trimmed to exclude the upper and lower 5% (arrow). (b) A curvilinear segment of a microtubule stained with alexa fluor 647 is traced and (c) the corresponding histogram and double gaussian fit generated. (d) gag-meos2 clusters, analyzed using a density-based clustering algorithm, which also allows to identify potential false localizations, i.e. Noise. (e) A microtubule section is rendered using the many rendering algorithms available. In order from 1 to 8: scatterplot, 2D histogram, blurred 2D histogram, kernel density estimation (a novel automatic bandwidth estimation rendering), delaunay triangulation, jittered histogram, hue-encoded depth, a novel occluding hue-encoded depth. (f) A 3D isosurface reconstruction of the microtubule section microtubule presented in e

Acknowledgements

The authors thank N. Olivier for providing the 3D microtubule data (Olivier et al., 2013) and J. Gunzenhäuser for the Gag-mEos2 data (Gunzenhauser et al., 2012).

Funding

TP was supported by the Brazilian Swiss Joint Research Programme of the EPFL and the SystemTB Collaborative Project (Ref. 241587), funded by EU FP7. SH and SM were supported by ERC Starting Grant 243016. SH was supported by a Marie Curie Intra-European Fellowship, PIEF-GA-2011-297918.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Baddeley D., et al. (2010) Visualization of localization microscopy data, Microsc. Microanal. Off. J. Microsc. Soc. Am. Microbeam Anal. Soc . Microsc. Soc. Can., 16, 64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betzig E., et al. (2006) Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science, 313, 1642–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botev Z.I., et al. (2010) Kernel density estimation via diffusion. Ann. Stat. 2010, 38, 2916–2957. [Google Scholar]

- El Beheiry M., Dahan M. (2013) ViSP: representing single-particle localizations in three dimensions. Nat. Methods, 10, 689–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endesfelder U., et al. (2013) Multiscale spatial organization of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. Biophys. J., 105, 172–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ester M.K., et al. (1996) A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, AAAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gunzenhauser J., et al. (2012) Quantitative super-resolution imaging reveals protein stoichiometry and nanoscale morphology of assembling HIV-Gag virions. Nano Lett., 12, 4705–4710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques R., et al. (2010) QuickPALM: 3D real-time photoactivation nanoscopy image processing in ImageJ. Nat. Methods, 7, 339–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaqaman K., et al. (2008) Robust single-particle tracking in live-cell time-lapse sequences. Nat. Methods, 5, 695–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu L., Yu J. (2008) Investigating intracellular dynamics of FtsZ cytoskeleton with photoactivation single-molecule tracking. Biophys. J., 95, 2009–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier N., et al. (2013) Resolution doubling in 3D-STORM imaging through improved buffers. PLoS One, 8, e69004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovesny M., et al. (2014) ThunderSTORM: a comprehensive ImageJ plug-in for PALM and STORM data analysis and super-resolution imaging. Bioinformatics, 30, 2389–2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G., et al. (2010) Superresolution imaging using single-molecule localization. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem., 61, 345–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengo T., Manley S. (2012) Software for the visualization and analysis of super-resolution localization microscopy data. In SSMLMS 2012, Aug 29–31 2012, Lausanne, Swizterland. [Google Scholar]

- Rust M.J., et al. (2006) Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). Nat. Methods, 3, 793–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter S., et al. (2012) rapidSTORM: accurate, fast open-source software for localization microscopy. Nat. Methods, 9, 1040–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]