Abstract

Although cells of monocytic lineage are the primary source of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) in the brain, other cell types in the central nervous system, including astrocytes, can harbor a latent or persistent HIV-1 infection. In the present study, we examined whether immature, multipotential human brain-derived progenitor cells (nestin positive) are also permissive for infection. When exposed to IIIB and NL4-3 strains of HIV-1, progenitor cells and progenitor-derived astrocytes became infected, with peak p24 levels of 100 to 500 pg/ml at 3 to 6 days postinfection. After 10 days, virus production was undetectable but could be stimulated by the addition of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). To bypass limitations to receptor entry, we compared the fate of infection in these cell populations by transfection with the infectious HIV-1 clone, pNL4-3. Again, transfected progenitors and astrocytes produced virus for 7 days but diminished to low levels beyond 8 days posttransfection. During the nonproductive phase, TNF-α stimulated virus production from progenitors as late as 5 weeks posttransfection. Astrocytes produced 5- to 20-fold more infectious virus (27 ng of p24/106 cells) than progenitors at the peak of 3 days posttransfection. Differentiation of infected progenitors toward an astrocyte phenotype increased virus production to levels consistent with infected astrocytes, suggesting a phenotypic difference in viral replication. Using this cell culture system of multipotential human brain-derived progenitor cells, we provide evidence that progenitor cells may be a reservoir for HIV-1 in the brains of AIDS patients.

A wide range of neurological problems is associated with AIDS, including the late-stage syndrome of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated dementia, which involves severe cognitive impairment, motor disturbances, and behavioral changes. In children infected perinatally, neurological dysfunction often involves developmental delays, with failure to gain new motor or cognitive skills, language deficits, behavioral problems, and chronic pain. Prior to the development of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the prevalence of HIV-associated neurological symptoms was estimated to be between 35 and 60% of adult AIDS patients and up to 90% of pediatric patients (23). Although these disorders have been reduced in the era of HAART (31, 42), partially due to the reduction in the prevalence of opportunistic infections in the central nervous system (CNS) (36), HIV-associated dementia is still estimated to occur in 10% of patients that develop AIDS (11), and less-severe symptoms of HIV encephalopathy (HIVE) continue to occur in up to 50% of patients (28, 32). This trend may reflect an increased life expectancy of patients successfully maintaining therapy (36) or the fact that some drugs used for therapy do not efficiently access the brain and, for those that do, there may be distinct neurotoxicity associated with treatment (27). In addition, systemic HIV type 1 (HIV-1) infection can develop resistance to therapy in 20 to 50% of patients (39). These observations suggest that systemic therapeutic approaches are not likely to eradicate the neurological consequences of HIV-1 infection, particularly if certain cell types harbor a latent infection.

Postmortem neuropathology has been observed in a majority of AIDS patients, particularly in children (47). The hallmarks of pathology in HIVE include microglial nodules and multinucleated giant cells in central white matter and deep gray matter, astrogliosis, neuron loss (particularly in hippocampus and basal ganglia), loss of synaptic connections, and myelin pallor (4, 16, 35). Although severe HIV-1-associated dementia is typically observed only during the late stages of infection, it is becoming increasingly evident that more subtle neuropsychological, neurophysiological, and neuroanatomical abnormalities in the context of HIVE are often observed before the end stages of AIDS (22). These observations suggest that HIV-1 encephalopathy is a gradual neurodegenerative process that, in many patients, begins early in the course of infection.

Most of the productively infected cells in the brain are microglia and macrophages, as shown by several studies using immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, and in situ PCR (2, 3, 17, 37, 48, 55, 57, 58). However, the amount of virus and the numbers of infected cells are generally too low to explain the extent of pathology observed (4, 16, 24, 35), suggesting that it is the cascade of cellular responses to infection (production of viral toxins, neurotoxins, and inflammatory factors), rather than the virus directly, that is primarily responsible for HIV-1-initiated neurological disease.

Due to the large number and crucial role of astrocytes in the brain, this cell type is believed to play a significant role in HIV-1-mediated neuropathology, both by serving as a possible reservoir for the virus and by impairment of function directly or indirectly caused by CNS infection. HIV-1 mRNA and DNA has been detected in astrocytes and neurons within the brains of adult and pediatric AIDS patients (5, 43, 46, 49, 52). Infection of human fetal brain-derived astrocytes in culture has been demonstrated with native virus, pseudotyped virus, and transfection of infectious HIV-1 clones (7, 25, 44, 50, 51). Pathology and cell culture studies suggest that pediatric or fetal astrocytes may be more susceptible to HIV-1 infection than adult astrocytes (43, 49).

It is unknown whether human progenitor cells in the developing brain are susceptible to HIV-1 infection. There is evidence that primary human neuroblasts, derived from fetal olfactory tissue, as well as neuroblastoma cell lines, can be infected by both BaL and IIIB strains of HIV-1 (13, 14). In those studies, the authors found that viral gene expression and LTR regulation differed depending on the specific lineage commitment pathway of each cell type. However, it is not clear whether multipotential cells earlier in the developmental pathway are susceptible to infection. If so, this population could be an important source of virus in the brains of pediatric AIDS patients and may partially explain some of the developmental delays observed in these patients.

Previous work in our laboratory described a cell culture system consisting of primary human brain-derived progenitor cells, which can differentiate into either astrocytes or neurons depending on culture conditions (33). This human fetal brain-derived, multipotential progenitor cell culture system was established by culturing as stable, attached cell layers in an actively proliferating, undifferentiated phenotype. These cells also can be grown as neurospheres, but growing as monolayer cultures allows greater flexibility in experimental design. By changing growth conditions, the cells can be induced to differentiate into highly purified populations of astrocytes or neurons, as described previously (33). The three phenotypes are distinguishable on the basis of morphology, cell marker expression, transcription factor production, and susceptibility to JC virus infection (33).

In the present study, we used the same cell culture system to understand the fate of HIV-1 infection in multipotential human brain progenitor cells compared to progenitor-derived astrocytes and neurons. For the first time we show evidence for infection in a subset of these undifferentiated cells, using both infection and transfection of HIV-1 IIIB and NL4-3 strains. We also explored the fate of infection during the process of differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Human brain-derived progenitor cells were obtained from 8-week-old fetal brain cultures and grown as monolayers on poly-d-lysine in serum-free neurobasal medium supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma), 2 mM glutamine, N2 (Invitrogen), neural survival factor (Clonetics, Walkersville, Md.), and the growth factors epidermal growth factor (20 ng/ml) plus basic FGF (25 ng/ml; Sigma), as described previously (33). Progenitor cell cultures were at least 98% positive for nestin staining and did not express GFAP. Cells were differentiated to an astrocyte phenotype by changing medium to Eagle minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 2 mM glutamine. Astrocytes differentiated for at least 3 weeks were 100% immunoreactive for GFAP expression and negative for nestin expression. Alternatively, progenitors were differentiated into a neuronal phenotype (MAP-2+, βIII-tubulin+, and negative for nestin) by changing the growth factors for at least 3 weeks to 10 ng of brain-derived neurotrophic factor/ml and 10 ng of platelet-derived growth factor A/B (Sigma)/ml.

RNA isolation and gene expression by RPA.

An RNase protection assay (RPA) was used to quantitate mRNA expression levels of chemokine receptors in progenitor, progenitor-derived astrocyte, and progenitor-derived neuron populations. Cells were plated at 70% confluence. The next day, some cultures were stimulated with 50 ng of recombinant human tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α; Roche)/ml. At either 4 or 16 h poststimulation, total RNA was isolated from each culture by using Qiagen's RNA-Easy minikits according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol (Qiagen). RPA was performed by using the RiboQuant RPA kits hCR5 and hCR6 (BD Biosciences). The hCR5 kit contained cDNA templates for CCR1, CCR3, CCR4, CCR5, TER1, and CCR2a/b; the hCR6 kit contained templates for CXCR1, CXCR2, CXCR3, CXCR4, BLR1, BLR2, and V28. Templates for housekeeping gene products L32 and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) were included as internal controls in both kits. Labeled antisense RNA probes were synthesized from these cDNA templates by using [α-32P]UTP (Perkin-Elmer Sciences) in an in vitro transcription reaction. Probes were then hybridized with 10 μg of total RNA from each condition. Probe synthesis, hybridization, and digestion with proteinase K and RNase were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol with modifications described previously (45). Samples were resolved on 5% denaturing acrylamide gels that were dried under vacuum at 80°C. Gels were then placed with autoradiographic film and exposed at −80°C for 6 to 24 h prior to development. The resulting bands were scanned and quantitated by using Scion Corp. (NIH Image) software, normalizing the intensity to that of GAPDH and L32 in the same reaction.

HIV-1 infection of progenitors and progenitor-derived astrocytes.

For infection studies, cell cultures at 60 to 70% confluence were incubated for 6 to 8 h with low serum virus stocks (IIIB or NL4-3) containing 11,600 pg of p24/ml in the presence of 20 μg of Polybrene/ml. After inoculation, cells were washed five times with media; fresh medium was added, and samples were obtained immediately for measuring viral protein.

For transfection experiments, the infectious full-length HIV-1 clone pNL4-3 was obtained from Malcolm Martin (1) through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health. Progenitor, astrocyte, and neuron cultures were seeded at 80% confluence in polylysine-coated 12-well plates. Cells were transfected for 5 h at 37° with 2 μg of pNL4-3 DNA and 1 μg of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) per well, diluted in a final volume of 1 ml of OptiMem medium (Invitrogen) per well. After 5 h, the transfection medium was removed and replaced with 2 ml of fresh medium. Control cultures in each experiment were transfected with pUC18. Using a construct for green fluorescent protein expression under the control of a cytomegalovirus promoter, transfection efficiency was ca. 40 to 60%, with <10% cell death compared to untransfected controls. Supernatants were collected at multiple times posttransfection; the medium was replaced after each collection. In long-term experiments for which samples were collected over 2 to 5 weeks, the cells were replated at a lower density as needed, and data were normalized on the basis of cell number as shown in Results. Cell free supernatant levels of p24 were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Zeptometrix Corp.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

T-cell infectivity.

Supernatants from pNL4-3-transfected astrocytes or progenitors were filtered, diluted, and incubated with cultures of the A3.01 T-cell line, which is normally susceptible to infection by the NL4-3 strain of HIV-1. Cells were washed extensively, and supernatants were collected for at least 12 days for ELISA determination of p24 production.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were fixed with 50% methanol-50% acetone, blocked with 1% BSA, and permeabilized with 0.02% Triton X-100. For visualization of viral protein, cells were then incubated with monoclonal mouse anti-p24, clone 39/5.4A (1:100; Zeptometrix Corp.) and goat anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate (1:100; Jackson Immunoresearch). For simultaneous immunostaining of viral protein and nestin, cells were also incubated with rabbit polyclonal antiserum against human nestin (34), followed by donkey anti-rabbit Rhodamine Red-X conjugate (1:100; Jackson Immunoresearch). For CXCR4 detection, uninfected fixed cells were incubated with mouse immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) anti-CXCR4 (1:100; R&D Systems), followed by goat anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate (1:100; Jackson Immunoresearch). Nuclei were identified by staining 10 min with Bis-Benzimide H (Calbiochem). Fluorescence-stained cultures were visualized by using either a Zeiss Axiovert S100 microscope or a Zeiss 510 laser confocal microscope, with standard wavelength settings for fluorescein (488 nm) and rhodamine (543 nm).

Flow cytometric (FACS) analysis.

Cell surface CXCR4 expression was examined by using live cells in normal physiological medium (10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, 145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 0.1% BSA). Cells were stained in suspension at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/100 μl, with 0.5 μg of mouse IgG2a anti-CXCR4, for 30 min (R&D Systems), followed by the addition of 0.25 μg of R-phycoerythrin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2a (Caltag Laboratories). Samples were analyzed by using a Becton Dickinson FACSVantage flow cytometer with argon ion laser excitation at 488 nm, a (575 ± 30)-nm filter set to detect emission, and CellQuest analysis software.

RESULTS

Transient HIV-1 infection in progenitor cells.

Previous work showed that primary human astrocytes support HIV-1 replication with transfection of the infectious clone NL4-3 (50, 51). We therefore tested whether NL4-3 or IIIB, CXCR4-binding strains of HIV-1, could infect progenitor cells or progenitor-derived astrocytes in our culture system. Cells were plated at a density of 200,000 cells per well in 12-well plates and were incubated with high titer, low-serum infectious stocks of IIIB and NL4-3, strains of HIV-1 that normally utilize CD4 and CXCR4 receptors for entry. At 6 h after exposure, cells were washed extensively as described in Materials and Methods. Immediately after the washing step and at different days postinfection, supernatants were collected and assayed for extracellular virus by p24 ELISA. Fresh medium was added after each collection.

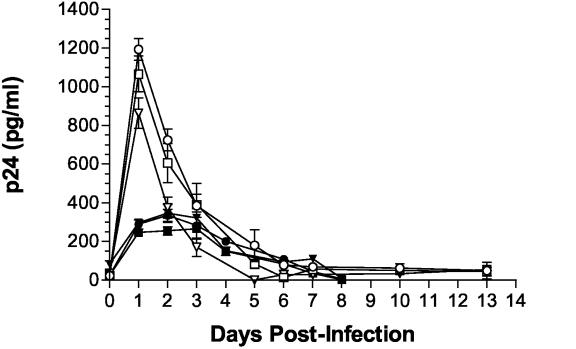

As shown in Fig. 1, both progenitors and astrocytes produced detectable levels of HIV-1 for at least 5 days postinfection. In three separate experiments, the peak virus production by progenitors was between 3 and 6 days postinfection. Virus production by astrocytes was highest at 1 day postinfection, but this may indicate the release of bound virus. Otherwise, the pattern of infection was very similar in the two cell types; by 10 to 15 days postinfection, p24 production from progenitor cells and astrocytes was no longer detected. These results were consistent with previous reports of restricted infection in primary and transformed astrocytes. Importantly, at 10 days postinfection, progenitors stimulated with TNF-α (50 ng/ml) produced detectable levels of p24, ca. 10% of the level produced at 3 days postinfection (data not shown). Together, these findings indicate that, like astrocytes, progenitor cells can support a restricted, latent infection that can be reactivated with inflammatory stimuli. When lower-titer viral stocks were used for infection of progenitors, peak virus levels were fivefold lower and occurred at 1 day postinfection, suggesting that a minimum concentration of viral particles may be required to get fusion and viral entry.

FIG. 1.

Productive HIV-1 infection of progenitor and progenitor-derived astrocyte cultures. Cells were plated at identical densities in polylysine-coated 12-well plates and incubated for 6 to 8 h with low-serum NL4-3 or IIIB virus (at least 10,000 pg of p24/ml plus 20 μg of Polybrene/ml). Reduced levels in FCS were used to prevent the initiation of progenitor differentiation. Media was replaced after each collection on days indicated. The data represent means ± the standard deviations for triplicate wells in each condition at each time point. Similar data were obtained in three separate experiments. Symbols: ○, Astro NL4-3, 5% FCS; □, Astro IIIB, 5% FCS; ▿, Astro IIIB, 1% FCS; •, Prog NL4-3, 5% FCS; ▪, Prog IIIB, 5% FCS; ▾, Prog IIIB, 1% FCS.

CXCR4 expression on human progenitor cells.

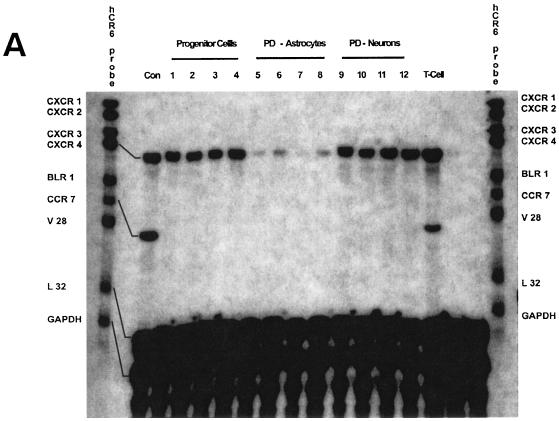

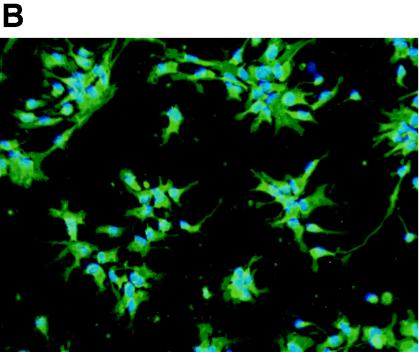

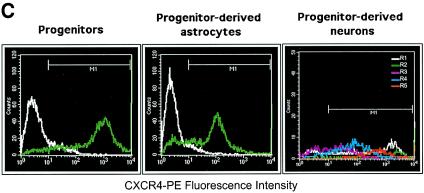

Because chemokine receptors may be involved in CD4-independent HIV-1 entry, we initially examined chemokine receptor expression on the undifferentiated human brain progenitor population. Monolayer cultures of multipotential progenitor cells were maintained as continually renewing cells or differentiated for 3 weeks to obtain astrocytes or neurons, as described in Materials and Methods. Using an RPA to evaluate multiple RNA messages, we found that only CXCR4 was expressed in progenitors, as well as in progenitor-derived astrocytes and neurons (Fig. 2A). The CXCR4 band intensity from each lane was quantified and normalized to the expression level of L32 in the same lane. Using this quantification method, we found that progenitors expressed 10-fold-higher levels of CXCR4 RNA compared to astrocytes; neuron expression was twofold greater than progenitors. Treatment with TNF-α slightly increased the level of CXCR4 expression in astrocytes but otherwise had no significant effect (even-numbered lanes). We found no evidence of CC receptor RNA or protein expression in any of these cell phenotypes (data not shown), which is consistent with previous reports, suggesting that HIV-1 coreceptors CCR3 and CCR5 are predominantly expressed in microglia (21, 29). CXCR4 protein expression in progenitor cells was confirmed by immunostaining and FACS analysis (Fig. 2B and C). FACS results indicated that 90% of progenitors expressed CXCR4, whereas 75% of astrocytes and 79% of neurons were positive for CXCR4. Importantly, the mean fluorescence intensity of CXCR4 staining in progenitor cells was nearly 10-fold higher than in astrocytes (Fig. 2C), indicating significantly higher surface expression that was consistent with the differences in RNA expression (Fig. 2A). A broad distribution of fluorescence intensity was observed in the total neuronal population, and analysis of the forward versus side scatter showed five distinct subpopulations, each with a different mean fluorescence intensity. The fluorescence histograms for individual neuronal populations are shown in Fig. 2C.

FIG. 2.

CXCR4 expression in human neural progenitor cells, astrocytes, and neurons. (A) Autoradiogram result of RPA for CC chemokine receptor expression in progenitors (lanes 1 to 4), progenitor-derived astrocytes (lanes 5 to 8), and progenitor-derived neurons (lanes 9 to 12). Cells were untreated (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11) or stimulated with TNF-α (50 ng/ml; lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12). Total RNA was collected after 4 h (lanes 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, and 10) or 16 h (lanes 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, and 12). (B) Overlay of immunofluorescence staining of CXCR4 (green) and nuclei (blue) of progenitor cells, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Magnification, ×180. (C) FACS histograms of CXCR4 cell surface staining in suspensions of live progenitor, progenitor-derived astrocyte, and progenitor-derived neuron cultures. For progenitors and astrocytes, the white histogram indicates staining with an isotype control antibody (mouse IgG2a), and the green histogram indicates CXCR4 staining. For neurons, CXCR4 fluorescence histograms are shown for each of five subpopulations based on forward versus side scatter. The mean fluorescence intensities for cells staining greater than background (M1 gate) and the percentages of cells with positive staining were as follows: progenitors, 1,067 (89% positive); astrocytes, 169 (75% positive); and neurons, 754 (79% positive). The mean fluorescence intensity values for the individual neuronal subpopulations were 1,047 (region 1), 2115 (region 2), 90 (region 3), 221 (region 4), and 757 (region 5).

Fate of infection of progenitors versus astrocytes after HIV-1 transfection.

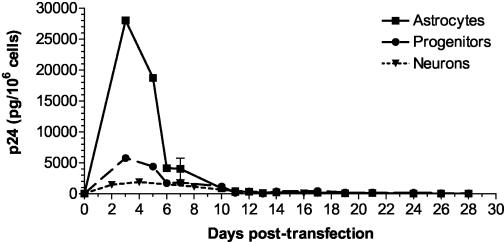

A lack of CD4 expression is likely to be at least partially responsible for the inefficient infection in progenitor cells and astrocytes. However, it is unclear whether intracellular events may also restrict productive infection in these populations. In order to bypass the receptor entry restrictions and compare the fate of infection in progenitor cells, astrocytes, and neuron populations, we maximized the proportion of infected cells by transfecting cell cultures with the infectious HIV-1 plasmid pNL4-3. The transfection efficiency of a control green fluorescent protein-expressing plasmid was 50 to 60% in progenitors and astrocytes and near 35% in neurons (data not shown). Supernatant samples, collected over 5 weeks, were tested by ELISA for the production of viral p24 protein. Progenitors and astrocytes produced large amounts of p24 over the first week, with a peak at 3 to 4 days posttransfection, as shown in Fig. 3. Virus production per million cells was fivefold greater in astrocyte cultures compared to progenitors. Cell-free supernatants from these transfected cells were infectious to A3.01 T cells, and the time needed for these supernatants to maximally infect T cells correlated with the p24 level (data not shown). At between 1.5 and 5 weeks posttransfection, low or undetectable levels of p24 were produced by both populations, indicating a persistent or latent infection.

FIG. 3.

HIV-1 production from pNL4-3-transfected progenitors, astrocytes, and neurons. After transfection with the infectious HIV-1 clone pNL4-3, supernatants were collected, and the medium was replaced on the days indicated. The data represent means and standard deviations for triplicate wells in each condition at each time point. Similar data were obtained in three separate experiments. Cell-free supernatants from each these cultures were infectious to T cells, and infectivity (time to reach maximal infection of T cells) correlated with p24 measurements.

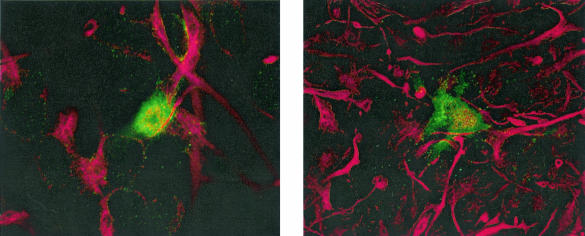

Coverslips were included in some wells at the time of plating. At multiple time points posttransfection, coverslips were fixed and stained for p24 antigen and either nestin (progenitor) or GFAP (astrocyte). Confocal microscopy confirmed that in each culture, pNL4-3 transfection resulted in intracellular p24 staining that colocalized with the appropriate neural cell marker. At between 3 and 6 days posttransfection, the time of maximal virus production, p24 antigen was visible in a small proportion of progenitors and astrocytes. Figure 4 shows an example of p24 and nestin colocalization in a progenitor cell, imaged by confocal microscopy. Similar numbers of infected cells were observed comparing the progenitors and astrocytes, ca. 0.5% of total cells, and the intensity of staining appeared greater in astrocytes. These results suggest that after transfection, virus replication in progenitors may be even more restricted than in astrocytes. This low number of infected cells compared to the near 50% transfection efficiency seen with control plasmids suggests that only a subpopulation of these cells may support infection.

FIG. 4.

Immunofluorescence of HIV-1-transfected progenitor cells. Cells plated on poly-d-lysine-coated German glass coverslips were transfected with pNL4-3, fixed 3 to 4 days posttransfection, and stained with mouse anti-p24 antibody and rabbit antiserum against human nestin. Appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies were visualized by confocal microscopy, and controls confirmed a lack of cross-reactivity. Green, HIV-1 p24; red,= nestin.

Inflammatory cytokine stimulation of virus production.

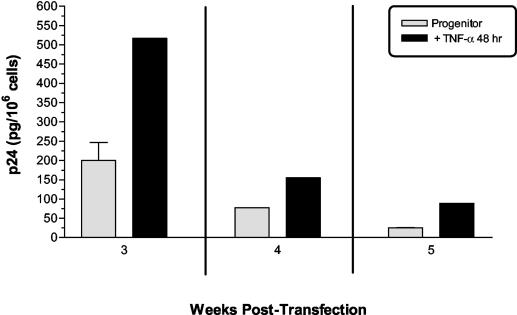

Because inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and interleukin-1β are known activators of latent HIV-1 infection in T cells, macrophages, and astrocytes, we hypothesized that virus production could be restimulated after infection of progenitors and astrocytes. At 3 weeks after transfection, both cell populations were exposed to TNF-α (10 to 100 ng/ml). A dose-dependent increase in virus production was observed (data not shown); 50 ng/ml was used for subsequent experiments since it provided optimal stimulation but was not toxic to the cells. At 3, 4, or 5 weeks posttransfection, a 48-h stimulation with 50 ng of TNF-α/ml resulted in a two- to threefold increase in progenitor virus production, as shown in Fig. 5. Similar effects were observed with transfected astrocytes, a finding consistent with previous studies (51). Supernatants from stimulated cells were infectious to T cells. In contrast, treatment with gamma interferon (100 U/ml) had no effect on virus production (data not shown). This finding, together with the TNF-α effect on infected progenitors described above, provides further evidence that progenitors, like astrocytes, are capable of harboring a latent or persistent infection that can be restimulated in the context of inflammatory factors.

FIG. 5.

Cytokine stimulation of HIV-1 production from transfected progenitor cells. At 3, 4, or 5 weeks after transfection with pNL4-3, progenitors or astrocytes were exposed for 48 h to TNF-α (50 ng/ml). The data represent mean values ± the standard deviations from supernatants sampled from triplicate wells of transfected progenitors.

Differentiation enhances virus production.

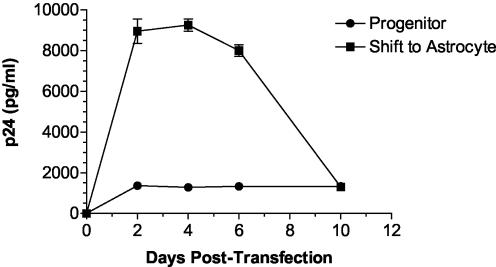

To further examine infection differences between undifferentiated and differentiated neuroglial populations, we tested the effect of differentiation on virus production from progenitor cells. Progenitors were transfected with pNL4-3 as before but, after transfection, the medium in some wells was changed to induce differentiation toward an astrocyte phenotype. Although complete differentiation requires 3 weeks for astrocytes in this model system, GFAP expression, chemokine production, and susceptibility to JCV infection are substantially increased within the first 3 days of differentiation (unpublished data).

When differentiation began immediately after transfection of progenitors, virus production increased up to fivefold within 2 days, as shown in Fig. 6. This increase was consistent with virus production after transfection of fully differentiated astrocytes. Similar results were found when differentiation was initiated later, even at 7 days posttransfection (Table 1), and in each case virus production in differentiating astrocytes remained higher than in progenitors for at least 10 days. There was no induction of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, that could explain the upregulation of virus production. Together, these results suggest that the differentiation-induced virus production represents a phenotypic difference in viral replication rather than in viral budding from progenitors and astrocytes.

FIG. 6.

Differentiation of pNL4-3-transfected progenitors toward an astrocyte phenotype stimulates virus production. Progenitors were plated and transfected with pNL4-3 as described earlier. Some wells were maintained as progenitors, whereas other wells were switched to astrocyte differentiation medium immediately after the transfection procedure. The data represent means ± the standard deviations of triplicate wells. Similar data were obtained in three separate experiments.

TABLE 1.

Time course of differentiation-induced reactivation of HIV-1 in progenitor cellsa

| Days post-transfection | Mean pg of p24/ml (SD) in:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progenitors | Shift to astrocytes (day 0) | Shift to astrocytes (day 3) | Shift to astrocytes (day 5) | Shift to astrocytes (day 7) | |

| 3 | 2,338 (3) | 6,751 (148) | |||

| 5 | 1,987 (61) | 4,241 (339) | 7,531 (215) | ||

| 7 | 1,499 (10) | 2,420 (57) | 4,702 (163) | 4,838 (356) | |

| 10 | 841 (10) | 1,911 (158) | 4,351 (284) | 3,973 (62) | 2,818 (24) |

| 12 | 232 (48) | 763 (21) | 3,796 (155) | 2,076 (549) | 1,059 (409) |

| 14 | 100 (1) | 2,108 (228) | 7,648 (722) | 5,847 (23) | 3,399 (117) |

| 17 | 128 (18) | 1,729 (262) | 6,137 (924) | 4,751 (412) | 3,440 (21) |

| 19 | 128 (9) | 655 (11) | 3,598 (320) | 3,576 (110) | 2,767 (14) |

| 21 | 100 (1) | 387 (1) | 3,813 (1,025) | 3,467 (203) | 2,412 (219) |

Progenitor cultures were plated in 12-well plates and transfected with pNL4-3 as described in the text. Cells were either maintained in progenitor medium or changed to astrocyte differentiation conditions at day 0 (immediately), day 3, day 5, or day 7 after transfection as indicated. Supernatants were collected at each time point indicated and tested by p24 ELISA for the presence of HIV-1. For each condition, the data represent mean (standard deviation) from duplicate ELISA measurements of supernatants pooled from triplicate cell culture wells.

DISCUSSION

Using a recently developed human brain-derived cell culture system that can be differentiated to an astrocyte or neuronal phenotype (33), we found that undifferentiated multipotential human progenitor cells isolated from fetal brain are permissive for HIV-1 infection. When progenitor cells were either infected or transfected with HIV-1, the result was an initial productive infection with high levels of p24 protein production (Fig. 1 and 3) that correlated with infectivity of T cells. After 3 to 6 days, virus production from progenitors diminished to very low or undetectable levels. Peak virus production from progenitor-derived astrocytes was slightly higher after infection (Fig. 1) and at least fivefold higher after HIV-1 DNA transfection (Fig. 3) but showed a similar pattern of decline, a finding consistent with our previous findings of infection in primary astrocytes (50, 51). Neurons, however, were much less permissive for infection, with minimal virus production after transfection (Fig. 3). Our findings are consistent with other studies of astrocyte infection (6, 9, 10, 41, 50, 51) and neuroblast infection (13, 14); however, this is the first report of HIV-1 infection in a multipotential brain progenitor population.

By immunostaining, we found that only a small proportion of nestin-positive progenitors supported infection (Fig. 4), despite high levels of CXCR4 expression (Fig. 2) and >50% transfection efficiency, indicating that only a subset of these progenitor cells is permissive for HIV-1 infection. Alternatively, it is possible that more cells were infected but developed a restricted infection immediately, with expression of only nonstructural viral genes.

As late as 5 weeks posttransfection with infectious NL4-3 HIV-1 DNA, TNF-α stimulated virus production from progenitors (Fig. 5), suggesting reactivation of a latent infection. Similar results were observed with progenitor-derived astrocytes, a finding consistent with our earlier work showing cytokine restimulation of infection in primary human astrocytes (51) and with reports of TNF-α-mediated HIV-1 reactivation in persistently infected monocyte and T-lymphocyte cell lines (15, 38). TNF-α, as well as other inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, are known to be produced in the brain during HIV-1-associated encephalopathy or dementia (18), so it is likely that any latently infected astrocytes or progenitor cells in the brain could be activated to produce virus at any point during the long course of disease.

One unique and interesting aspect of the present study was that differentiation of HIV-1-infected progenitors toward an astrocyte phenotype immediately increased virus production at least fivefold (Fig. 6 and Table 1). This stimulation of viral replication occurred even when differentiation was initiated at 7 days posttransfection, when virus production had been substantially reduced. These findings provide further evidence for lineage-specific differences in the fate of infection and for the ability of progenitor cells to harbor infection.

Since progenitors and astrocytes do not express CD4, viral entry is inefficient and the levels of viral message and protein are very low compared to a productive macrophage or T-cell infection. Some reports suggest that the primary restriction for astrocytes infection is at the level of receptor entry: astrocytes transfected with expression vectors for CD4 and CXCR4 (44) or infected with a pseudotyped virus containing an envelope gene from VSV (7) can support a highly productive infection with HIV-1. In contrast, other studies have found that after an initially productive infection in astrocytes, even with enhanced expression of CD4 and CXCR4 receptors, virus production falls to very low or undetectable levels, with preferential expression of nonstructural viral genes (6, 9, 10, 25, 50, 51). This persistent or latent infection can be reactivated by exposure to inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and interleukin-1β (51). There may be restrictions to virion processing once the virus enters these cells. These issues have not yet been addressed in the brain progenitor cell population.

The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is known to be a major coreceptor for HIV-1 and has been implicated in CD4-independent entry of some isolates of HIV-2 (12). Although several studies have determined that CXCR4 is not involved in CD4-independent HIV-1 infection (19-21, 30, 41), there is evidence that HIV-1 gp120 binding to CXCR4 on the cell surface of astrocytes can result in impaired excitatory amino acid transport (26, 56). It is possible that some isolates of HIV-1, particularly those that are unique to the brain, may utilize CXCR4 either to infect or to exert functional effects on progenitors and/or astrocytes. In our system, the level of CXCR4 expression (by RNA and FACS analyses) was 10-fold greater in progenitors compared to astrocytes (Fig. 2), suggesting that progenitors may be more susceptible than astrocytes to effects of HIV-1. However, it is not known whether this is also true in vivo and whether there are differences in expression between fetal, pediatric, and adult cells.

In the periphery, there is evidence that bone marrow-derived CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells are impaired when exposed to HIV-1 infection; however, there are few reports of infection in this cell type. Mixed populations of bone marrow cells in the presence of HIV-1 show impaired mesenchymal stem cell colony formation, but this was not due to direct infection (54). A study of T-cell progenitors from AIDS patients showed impaired differentiation, which might contribute to T-cell depletion (8). In another report, two CD34+ human hematopoietic progenitor cell lines, KG-1 and TF-1, became susceptible to HIV-1 infection via upregulation of CD4 expression in the presence of a concurrent infection by human herpesvirus 6 (53). A recent study examined cellular factors involved in regulation of HIV-1 in the TF-1 cell line (40), a model for human bone marrow-derived hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Our findings show that there may be a subpopulation of progenitor cells particularly susceptible to HIV-1 infection. Future studies will focus on the characteristics of susceptible cells, as well as whether there are functional consequences of infection in this subpopulation. In addition, because we detected CXCR4 expression on a large proportion of progenitor cells, there may be functional consequences of exposure to virus or gp120 independent of infection. HIV-1-infected or exposed progenitor cells might be expected to have impaired proliferation or differentiation capacity, or they might differentiate into functionally impaired glial or neuronal cells. Therefore, it is possible that neuron-derived progenitor cells, particularly in the developing brain, might contribute to the developmental problems in pediatric HIVE.

In summary, we have found that multipotential human brain-derived progenitor cells and progenitor-derived astrocytes, but not progenitor-derived neurons, are permissive for HIV-1 and support a latent infection that can be reactivated by differentiation or cytokine stimulation. Progenitor cells in the brain therefore may represent an additional reservoir for HIV-1. These cells may be a source of infected and/or impaired astrocytes in pediatric cases of HIV-1 encephalopathy. These cells may also represent long-term targets for infection in adult patients, who are often living with the infection for 2 or 3 decades before signs of neurological damage are apparent. The ability to isolate and differentiate CNS progenitor cells in culture will allow studies addressing functional and neurodevelopmental consequences of progenitor cell infection in the brain.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the technical contributions from Carolyn Smith, of the NINDS light imaging facility, for confocal microscopy imaging.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi, A., H. E. Gendelman, S. Koenig, T. Folks, R. Willey, A. Rabson, and M. A. Martin. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An, S. F., M. Groves, B. Giometto, A. A. Beckett, and F. Scaravilli. 1999. Detection and localisation of HIV-1 DNA and RNA in fixed adult AIDS brain by polymerase chain reaction/in situ hybridisation technique. Acta Neuropathol. 98:481-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagasra, O., E. Lavi, L. Bobroski, K. Khalili, J. P. Pestaner, R. Tawadros, and R. J. Pomerantz. 1996. Cellular reservoirs of HIV-1 in the central nervous system of infected individuals: identification by the combination of in situ polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry. AIDS 10:573-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell, J. E. 1998. The neuropathology of adult HIV infection. Rev. Neurol. 154:816-829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brack-Werner, R. 1999. Astrocytes: HIV cellular reservoirs and important participants in neuropathogenesis. AIDS 13:1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brengel-Pesce, K., P. Innocenti-Francillard, P. Morand, B. Chanzy, and J. M. Seigneurin. 1997. Transient infection of astrocytes with HIV-1 primary isolates derived from patients with or without AIDS dementia complex. J. Neurovirol. 3:449-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canki, M., J. N. Thai, W. Chao, A. Ghorpade, M. J. Potash, and D. J. Volsky. 2001. Highly productive infection with pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) indicates no intracellular restrictions to HIV-1 replication in primary human astrocytes. J. Virol. 75:7925-7933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark, D. R., S. Repping, N. G. Pakker, J. M. Prins, D. W. Notermans, F. W. Wit, P. Reiss, S. A. Danner, R. A. Coutinho, J. M. Lange, and F. Miedema. 2000. T-cell progenitor function during progressive human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection and after antiretroviral therapy. Blood 96:242-249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dewhurst, S., K. Sakai, J. Bresser, M. Stevenson, M. J. Evinger-Hodges, and D. J. Volsky. 1987. Persistent productive infection of human glial cells by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and by infectious molecular clones of HIV. J. Virol. 61:3774-3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Rienzo, A. M., F. Aloisi, A. C. Santarcangelo, C. Palladino, E. Olivetta, D. Genovese, P. Verani, and G. Levi. 1998. Virological and molecular parameters of HIV-1 infection of human embryonic astrocytes. Arch. Virol. 143:1599-1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dougherty, R. H., R. L. Skolasky, Jr., and J. C. McArthur. 2002. Progression of HIV-associated dementia treated with HAART. AIDS Read 12:69-74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Endres, M. J., P. R. Clapham, M. Marsh, M. Ahuja, J. D. Turner, A. McKnight, J. F. Thomas, B. Stoebenau-Haggarty, S. Choe, P. J. Vance, T. N. Wells, C. A. Power, S. S. Sutterwala, R. W. Doms, N. R. Landau, and J. A. Hoxie. 1996. CD4-independent infection by HIV-2 is mediated by fusin/CXCR4. Cell 87:745-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ensoli, F., A. Cafaro, V. Fiorelli, B. Vannelli, B. Ensoli, and C. J. Thiele. 1995. HIV-1 infection of primary human neuroblasts. Virology 210:221-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ensoli, F., H. Wang, V. Fiorelli, S. L. Zeichner, M. R. De Cristofaro, G. Luzi, and C. J. Thiele. 1997. HIV-1 infection and the developing nervous system: lineage-specific regulation of viral gene expression and replication in distinct neuronal precursors. J. Neurovirol. 3:290-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folks, T. M., K. A. Clouse, J. Justement, A. Rabson, E. Duh, J. H. Kehrl, and A. S. Fauci. 1989. Tumor necrosis factor alpha induces expression of human immunodeficiency virus in a chronically infected T-cell clone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:2365-2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gendelman, H. E., S. A. Lipton, M. Tardieu, M. I. Bukrinsky, and H. S. Nottet. 1994. The neuropathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 56:389-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glass, J. D., H. Fedor, S. L. Wesselingh, and J. C. McArthur. 1995. Immunocytochemical quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus in the brain: correlations with dementia. Ann. Neurol. 38:755-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimaldi, L. M., G. V. Martino, D. M. Franciotta, R. Brustia, A. Castagna, R. Pristera, and A. Lazzarin. 1991. Elevated alpha-tumor necrosis factor levels in spinal fluid from HIV-1-infected patients with central nervous system involvement. Ann. Neurol. 29:21-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hao, H. N., F. C. Chiu, L. Losev, K. M. Weidenheim, W. K. Rashbaum, and W. D. Lyman. 1997. HIV infection of human fetal neural cells is mediated by gp120 binding to a cell membrane-associated molecule that is not CD4 nor galactocerebroside. Brain Res. 764:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hao, H. N., and W. D. Lyman. 1999. HIV infection of fetal human astrocytes: the potential role of a receptor-mediated endocytic pathway. Brain Res. 823:24-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He, J., Y. Chen, M. Farzan, H. Choe, A. Ohagen, S. Gartner, J. Busciglio, X. Yang, W. Hofmann, W. Newman, C. R. Mackay, J. Sodroski, and D. Gabuzda. 1997. CCR3 and CCR5 are coreceptors for HIV-1 infection of microglia. Nature 385:645-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heaton, R. K., I. Grant, N. Butters, D. A. White, D. Kirson, J. H. Atkinson, J. A. McCutchan, M. J. Taylor, M. D. Kelly, R. J. Ellis, et al. 1995. The HNRC 500: neuropsychology of HIV infection at different disease stages. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 1:231-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen, R. S., D. R. Cornblath, L. G. Epstein, J. McArthur, and R. W. Price. 1989. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and the nervous system: report from the American Academy of Neurology AIDS Task Force. Neurology 39:119-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaul, M., G. A. Garden, and S. A. Lipton. 2001. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia. Nature 410:988-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keir, S. D., J. Miller, G. Yu, R. Hamilton, R. J. Samulski, X. Xiao, and C. Tornatore. 1997. Efficient gene transfer into primary and immortalized human fetal glial cells using adeno-associated virus vectors: establishment of a glial cell line with a functional CD4 receptor. J. Neurovirol. 3:322-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kort, J. J. 1998. Impairment of excitatory amino acid transport in astroglial cells infected with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:1329-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langford, T. D., S. L. Letendre, G. J. Larrea, and E. Masliah. 2003. Changing patterns in the neuropathogenesis of HIV during the HAART era. Brain Pathol. 13:195-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanska, D. J. 1999. Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus infection and associated neurologic illness. Semin. Neurol. 19:105-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavi, E., J. M. Strizki, A. M. Ulrich, W. Zhang, L. Fu, Q. Wang, M. O'Connor, J. A. Hoxie, and F. Gonzalez-Scarano. 1997. CXCR-4 (Fusin), a coreceptor for the type 1 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1), is expressed in the human brain in a variety of cell types, including microglia and neurons. Am. J. Pathol. 151:1035-1042. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma, M., J. D. Geiger, and A. Nath. 1994. Characterization of a novel binding site for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein gp120 on human fetal astrocytes. J. Virol. 68:6824-6828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maschke, M., O. Kastrup, S. Esser, B. Ross, U. Hengge, and A. Hufnagel. 2000. Incidence and prevalence of neurological disorders associated with HIV since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 69:376-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masliah, E., R. M. DeTeresa, M. E. Mallory, and L. A. Hansen. 2000. Changes in pathological findings at autopsy in AIDS cases for the last 15 years. AIDS 14:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Messam, C. A., J. Hou, R. M. Gronostajski, and E. O. Major. 2003. Lineage pathway of human brain progenitor cells identified by JC virus susceptibility. Ann. Neurol. 53:636-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Messam, C. A., J. Hou, and E. O. Major. 2000. Coexpression of nestin in neural and glial cells in the developing human CNS defined by a human-specific anti-nestin antibody. Exp. Neurol. 161:585-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nath, A. 1999. Pathobiology of human immunodeficiency virus dementia. Semin. Neurol. 19:113-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neuenburg, J. K., H. R. Brodt, B. G. Herndier, M. Bickel, P. Bacchetti, R. W. Price, R. M. Grant, and W. Schlote. 2002. HIV-related neuropathology, 1985 to 1999: rising prevalence of HIV encephalopathy in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 31:171-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nuovo, G. J., F. Gallery, P. MacConnell, and A. Braun. 1994. In situ detection of polymerase chain reaction-amplified HIV-1 nucleic acids and tumor necrosis factor-alpha RNA in the central nervous system. Am. J. Pathol. 144:659-666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poli, G., A. Kinter, J. S. Justement, J. H. Kehrl, P. Bressler, S. Stanley, and A. S. Fauci. 1990. Tumor necrosis factor alpha functions in an autocrine manner in the induction of human immunodeficiency virus expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:782-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powderly, W. G. 2000. Current approaches to treatment for HIV-1 infection. J. Neurovirol 6(Suppl. 1):S8-S13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quiterio, S., C. Grant, T. H. Hogan, F. C. Krebs, and B. Wigdahl. 2003. C/EBP- and Tat-mediated activation of the HIV-1 LTR in CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 57:49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabri, F., E. Tresoldi, M. Di Stefano, S. Polo, M. C. Monaco, A. Verani, J. R. Fiore, P. Lusso, E. Major, F. Chiodi, and G. Scarlatti. 1999. Nonproductive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of human fetal astrocytes: independence from CD4 and major chemokine receptors. Virology 264:370-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sacktor, N., R. H. Lyles, R. Skolasky, C. Kleeberger, O. A. Selnes, E. N. Miller, J. T. Becker, B. Cohen, and J. C. McArthur. 2001. HIV-associated neurologic disease incidence changes: Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, 1990-1998. Neurology 56:257-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saito, Y., L. R. Sharer, L. G. Epstein, J. Michaels, M. Mintz, M. Louder, K. Golding, T. A. Cvetkovich, and B. M. Blumberg. 1994. Overexpression of nef as a marker for restricted HIV-1 infection of astrocytes in postmortem pediatric central nervous tissues. Neurology 44:474-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schweighardt, B., and W. J. Atwood. 2001. HIV type 1 infection of human astrocytes is restricted by inefficient viral entry. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:1133-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seth, P., M. M. Husain, P. Gupta, A. Schoneboom, B. F. Grieder, H. Mani, and R. K. Maheshwari. 2003. Early onset of virus infection and upregulation of cytokines in mice treated with cadmium and manganese. Biometals 16:359-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharer, L. R., Y. Saito, L. G. Epstein, and B. M. Blumberg. 1994. Detection of HIV-1 DNA in pediatric AIDS brain tissue by two-step ISPCR. Adv. Neuroimmunol. 4:283-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simpson, D. M. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia: review of pathogenesis, prophylaxis, and treatment studies of zidovudine therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:19-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi, K., S. L. Wesselingh, D. E. Griffin, J. C. McArthur, R. T. Johnson, and J. D. Glass. 1996. Localization of HIV-1 in human brain using polymerase chain reaction/in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. Ann. Neurol. 39:705-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tornatore, C., R. Chandra, J. R. Berger, and E. O. Major. 1994. HIV-1 infection of subcortical astrocytes in the pediatric central nervous system. Neurology 44:481-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tornatore, C., K. Meyers, W. Atwood, K. Conant, and E. Major. 1994. Temporal patterns of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcripts in human fetal astrocytes. J. Virol. 68:93-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tornatore, C., A. Nath, K. Amemiya, and E. O. Major. 1991. Persistent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in human fetal glial cells reactivated by T-cell factor(s) or by the cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1 beta. J. Virol. 65:6094-6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trillo-Pazos, G., A. Diamanturos, L. Rislove, T. Menza, W. Chao, P. Belem, S. Sadiq, S. Morgello, L. Sharer, and D. J. Volsky. 2003. Detection of HIV-1 DNA in microglia/macrophages, astrocytes and neurons isolated from brain tissue with HIV-1 encephalitis by laser capture microdissection. Brain Pathol. 13:144-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vignoli, M., G. Furlini, M. C. Re, E. Ramazzotti, and M. La Placa. 2000. Modulation of CD4, CXCR-4, and CCR-5 makes human hematopoietic progenitor cell lines infected with human herpesvirus-6 susceptible to human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Hematother Stem Cell Res. 9:39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang, L., D. Mondal, V. F. La Russa, and K. C. Agrawal. 2002. Suppression of clonogenic potential of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by HIV type 1: putative role of HIV type 1 tat protein and inflammatory cytokines. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 18:917-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang, T. H., Y. K. Donaldson, R. P. Brettle, J. E. Bell, and P. Simmonds. 2001. Identification of shared populations of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infecting microglia and tissue macrophages outside the central nervous system. J. Virol. 75:11686-11699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang, Z., O. Pekarskaya, M. Bencheikh, W. Chao, H. A. Gelbard, A. Ghorpade, J. D. Rothstein, and D. J. Volsky. 2003. Reduced expression of glutamate transporter EAAT2 and impaired glutamate transport in human primary astrocytes exposed to HIV-1 or gp120. Virology 312:60-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiley, C. A. 1996. Polymerase chain reaction in situ hybridization: opening Pandora's box? Ann. Neurol. 39:691-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wiley, C. A., R. D. Schrier, J. A. Nelson, P. W. Lampert, and M. B. Oldstone. 1986. Cellular localization of human immunodeficiency virus infection within the brains of acquired immune deficiency syndrome patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:7089-7093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]