Abstract

Rat models of focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury were established by occlusion of the middle cerebral artery. Microarray analysis showed that 24 hours after cerebral ischemia, there were nine up-regulated and 27 down-regulated microRNA genes in cortical tissue. Bioinformatic analysis showed that bcl-2 was the target gene of microRNA-384-5p and microRNA-494, and caspase-3 was the target gene of microRNA-129, microRNA-320 and microRNA-326. Real-time PCR and western blot analyses showed that 24 hours after cerebral ischemia, bcl-2 mRNA and protein levels in brain tissue were significantly decreased, while caspase-3 mRNA and protein levels were significantly increased. This suggests that following cerebral ischemia, differentially expressed microRNA-384-5p, microRNA-494, microRNA-320, microRNA-129 and microRNA-326 can regulate bcl-2 and caspase-3 expression in brain tissue.

Keywords: focal cerebral ischemia, microRNA, apoptosis, bcl-2, caspase-3, neural regeneration

Abbreviations:

miRNAs, microRNAs; MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion

INTRODUCTION

Many complex pathophysiological mechanisms underlie ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Recent evidence suggests that progression of ischemic cerebrovascular disease predominantly results from neural cell death following cerebral ischemia. Apoptosis is an important component of the sequence of events in ischemic cerebrovascular disease and is also one of the major pathways that leads to the process of cell death[1]. Therefore, it is of importance to administer anti-apoptotic treatment as early as possible following cerebral ischemia. However, the precise mechanisms underlying stroke-induced neuronal death and neurological dysfunction are not fully understood. The elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of cell death will provide new insights into the development of neuroprotective agents for stroke therapeutics.

The discovery of microRNAs (miRNAs) has broadened our understanding of the mechanisms that regulate gene expression with the addition of an entirely new level of regulatory control. miRNAs modulate protein levels by binding to complementary or partially complementary target mRNAs and thereby targeting the mRNA for degradation or translational inhibition[2,3,4].

At present, over several hundred miRNAs have been confirmed in the human genome[5] and they can regulate at least 30% of human gene expression. miRNAs participate in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, embryonic development and morphogenesis, while abnormally expressed or activated miRNAs can lead to disease occurrence[2,6,7,8]. Approximately 70% of known miRNAs are expressed in the mammalian brain and miRNAs are involved in the physiological and pathological processes of many neurological diseases, such as brain tumors, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Down's syndrome, schizophrenia, and stroke[9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. However, the importance of miRNAs in the pathogenesis of ischemic brain damage is largely unknown, especially their effect on apoptosis, and on the regulation of the key apoptotic genes, bcl-2 and caspase-3. Therefore, we adopted microarray analysis to investigate the expression profiles of miRNAs in brain tissue after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. We also examined the differentially expressed miRNAs with respect to apoptosis-related proteins to provide a new approach to the study of cerebral ischemia pathogenesis.

RESULTS

Quantitative analysis of experimental animals

Twelve rats were assigned to an experimental group, in which transient focal cerebral ischemia/ reperfusion injury was induced by occlusion of the middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), and eight rats were assigned to a sham-surgery group, in which, only sutured insertions were performed without MCAO. All 20 rats were included in the final analysis.

Behavioral changes of the rat models of cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

Before surgery, the sham-surgery group rats and MCAO group rats were tested for neurological deficits by Longa's method and all animals were scored 0. After surgery, in the MCAO group, four rats were scored 1, four rats scored 2, three rats scored 3, and one rat scored 4, with a mean score of 1.83. Higher scores indicate more severe behavioral dysfunction induced by cerebral ischemia. All rats in the sham-surgery group were scored 0 after surgery.

miRNA expression in rat brain tissue following transient focal cerebral ischemia

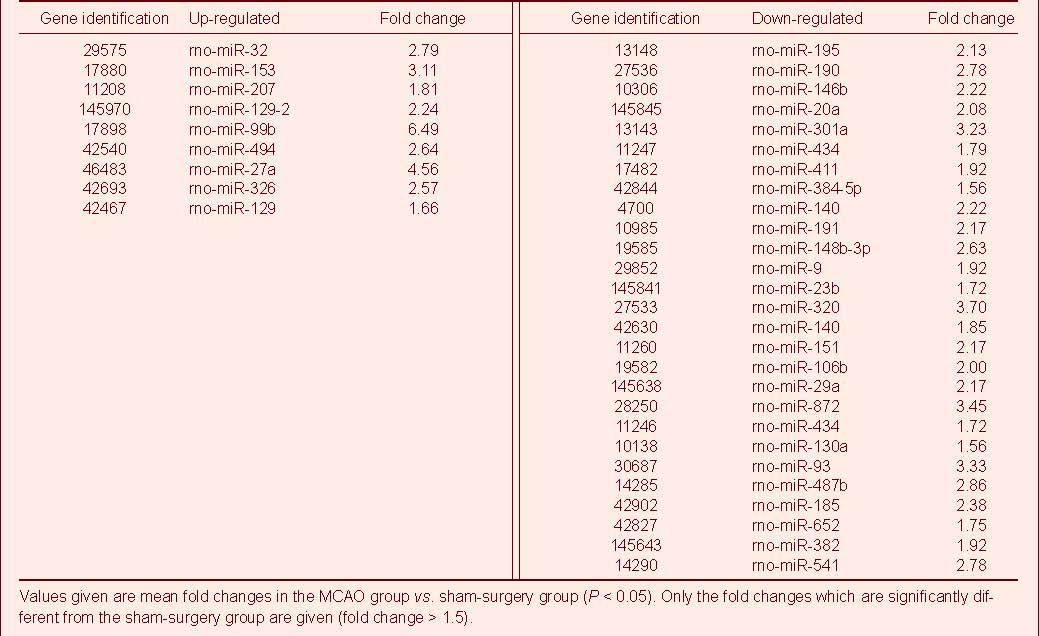

Microarray analysis was used to detect miRNA expression changes in cortical tissue following MCAO. Twenty-four hours after MCAO, there were 36 differentially expressed miRNAs in the MCAO group (> 1.5-fold change), including nine up-regulated (two-sample t-test; P < 0.05) and 27 down-regulated (two-sample t-test; P < 0.05), compared with the sham-surgery group Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1.

Differential expression of microRNAs in rat brain tissue following middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO)

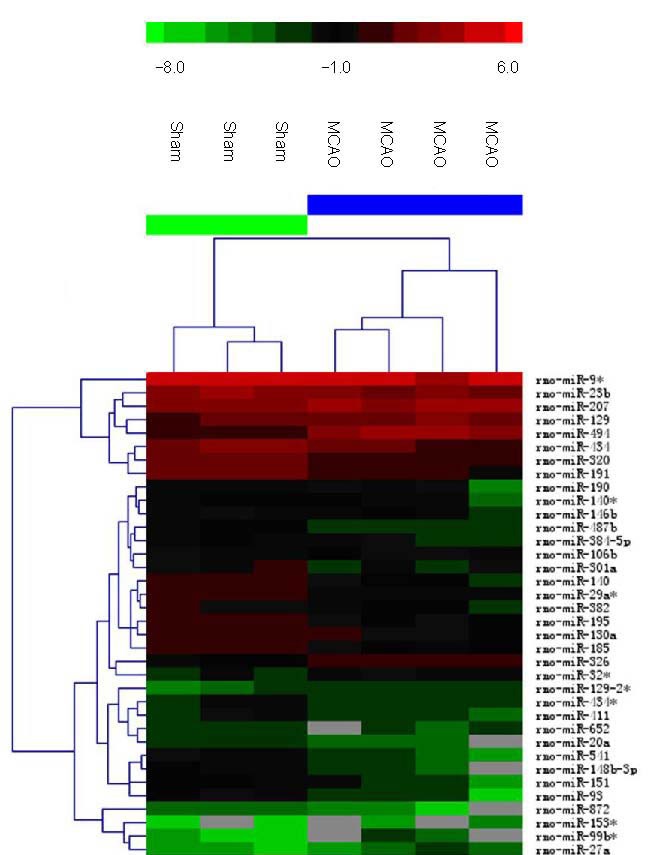

Figure 1.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of microRNAs (miRNAs) with significantly altered expression in rat brain after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO).

The color code in the heat map is linear with green as the lowest and red as the highest. The miRNAs whose expression increased are shown in green to red, whereas the miRNAs whose expression decreased are shown from red to green.

The figure shows the data from seven individual microarrays. The individual expression signal of each miRNA in each array was clustered using Euclidean distance function. Sham: Sham-surgery group.

Bioinformatic analysis of microarray results

miRNAs targeting caspase-3 and bcl-2 were analyzed using TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org), PicTar (http://pictar.mdc-berlin.de) and miRanda (http://www.microrna.org) bioinformation databases. Among the miRNAs that were significantly differentially expressed, miR-384-5p and miR-494 targeted bcl-2, and miR-320, miR-129 and miR-326 targeted caspase-3.

bcl-2, caspase-3 and miRNA expression in rat brain tissue following MCAO

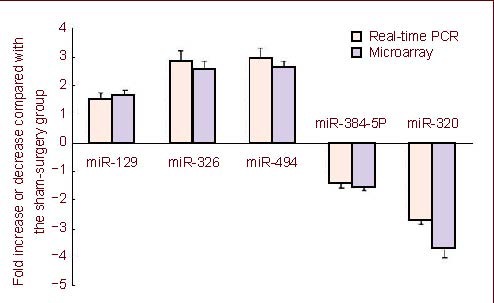

Real-time PCR was used to validate whether the expression of bcl-2 and caspase-3 was consistent with the microarray results for the above five miRNAs. Twenty-four hours after MCAO, expression of miR-129, miR-326, miR-494, miR-384-5p and miR-320 was detected by real-time PCR and expression for each miRNA was similar to the microarray results (Figure 2). Bcl-2 and caspase-3 expression in brain samples was also quantified by real-time PCR. There were significant changes in the mRNA levels of bcl-2 and caspase-3, 24 hours after reperfusion compared with the sham-surgery group (P < 0.05) (Figure 3); bcl-2 mRNA levels were significantly decreased (P < 0.05) and caspase-3 mRNA levels were significantly increased in the MCAO group (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Real-time PCR analysis confirmed the expression level of the five differentially expressed microRNAs (miRNAs) 24 hours after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), as observed by microarray analysis.

The expression level of the five miRNAs was consistent with that observed by microarray analysis. These five miRNAs include miR-129, miR-326, miR-494, miR-384-5p and miR-320. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3; two-sample t-test).

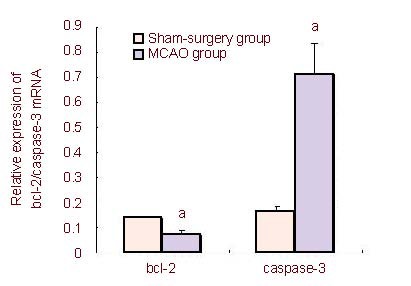

Figure 3.

Real-time PCR detection of bcl-2 and caspase-3 mRNA levels in rat brain tissue following middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) (mean ± SD).

Compared with the sham-surgery group, bcl-2 mRNA levels were significantly decreased and caspase-3 mRNA levels were significantly increased in the MCAO group.

Data are expressed as absorbance ratio of target gene to glyceraldhyde phosphate dehydrogenase (n = 3; two-sample t-test). aP < 0.05, vs. sham-surgery group.

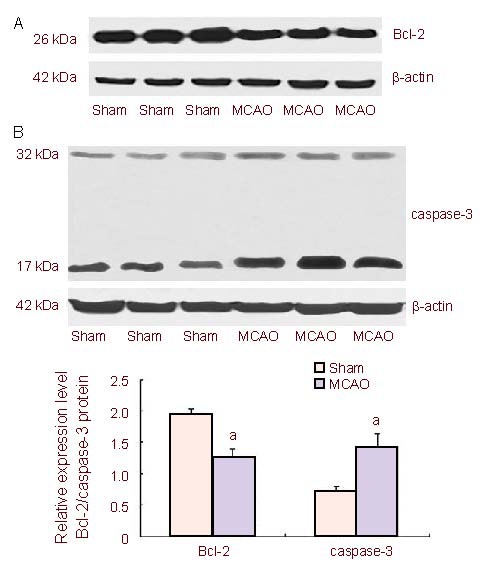

Bcl-2 and caspase-3 protein levels in rat brain tissue following MCAO

Western blot analysis was used to detect the protein levels of bcl-2 and caspase-3 in rat brain tissue. Compared with the sham-surgery group, 24 hours after cerebral ischemia, Bcl-2 protein levels were significantly decreased (P < 0.01) and caspase-3 protein levels were significantly increased (P < 0.01) in the MCAO group (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Bcl-2 (A) and caspase-3 (B) protein levels in the brain tissue of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) rats 24 hours after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion (mean ± SD).

Compared with the sham-surgery (sham) group, the levels of Bcl-2 protein were significantly decreased and the levels of caspase-3 protein were significantly increased in the MCAO group.

Data are expressed as absorbance ratio of target protein to β-actin (n = 3, two-sample t-test). aP < 0.01, vs. sham-surgery group.

DISCUSSION

The recent discovery of miRNAs as key regulators of gene function has introduced a new level and mechanism of gene regulation[2,3,4]. An increasing number of studies provide strong evidence that miRNAs are abundantly expressed in the nervous system and are critical mediators in the regulation of neural development and plasticity[5]. Dysfunction of the miRNA network has emerged as a major factor in neurological diseases. Results from this study show that focal ischemia leads to extensive changes in cerebral miRNA expression in rodents, and similar findings have been reported by others[18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. This suggests the potential importance of miRNA dysfunction in the pathogenesis of stroke. Cellular apoptosis is an established characteristic of neuronal death following cerebral ischemia; after ischemia, apoptotic cells tend to exist in mild or moderate ischemic penumbra regions (such as in the cerebral cortex), while cell apoptosis due to MCAO induction occurs primarily 24 hours after ischemia[25]. For this reason, in this study, we detected miRNA changes in MCAO rat cerebral tissue 24 hours after ischemia. Our results show clearly up- or down-regulated miRNAs, which are partially consistent with previous findings; however, in previous studies, not all differentially expressed miRNAs are the same[14,15]. It is likely that differences among our study and previous studies are related to ischemia time, reperfusion time, animal species and different regions for sample harvesting.

Extensive research has demonstrated that apoptosis plays a critical role in neuronal death after focal cerebral ischemia[26]. Cellular apoptosis is regulated by many genes, and bcl-2 and caspase-3 are two controlling genes. bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic gene, is the key gene for inhibiting cellular apoptosis by many means and thereby protecting and prolonging cell lifespan[27]. Caspase-3, a pro-apoptotic gene, is the key apoptosis executor in the caspase cascade and plays a final pivotal role during apoptosis induced by various factors[28,29]. This study shows that the levels of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins were significantly decreased and the levels of the pro-apoptotic Caspase-3 protein were significantly increased in the brain tissue 24 hours after reperfusion following MCAO in rats. These results indicate that apoptosis-related proteins play a role in focal cerebral ischemia. Recently, Bcl-2 and caspase-3 have been considered as therapeutic targets and regulation of Bcl-2 and caspase-3 expression protects against ischemic brain injury[25,30,31]. An increasing number of miRNAs have been found to regulate pro-and anti-apoptotic genes in apoptotic signaling pathways[32,33,34]. The elucidation of miRNA mechanisms involved in apoptosis may be important for understanding the pathogenesis of cerebral ischemia. However, very few studies have investigated the functional significance and molecular mechanisms of individual miRNAs in cerebral post-ischemic neuronal death. Recently, several software programs, such as TargetScan, PicTar and miRanda have been developed as very useful tools for performing miRNA target prediction[35]. Focal ischemia in rat brain regulates the expression of miRNAs predicted to target proteins known to mediate inflammation, transcription, neuroprotection, receptor function, and ionic homeostasis in the brain[14]. In this study, we focused our bioinformatic studies on identifying those miRNAs involved in apoptosis after ischemic insult. We show that bcl-2 is a target gene of miR-384-5p and miR-494 and caspase-3 is a target gene of miR-320, miR-129 and miR-326. This suggests that these miRNAs may regulate translation of Bcl-2 and caspase-3 proteins. Results from this study also show that Bcl-2 levels were significantly decreased and caspase-3 levels were significantly increased in the rat cerebral cortex after focal cerebral ischemia. This suggests that the five miRNAs regulating Bcl-2 and caspase-3 may become a potential therapeutic option for stroke related brain injury. However, Bioinformatic analysis only provides miRNA target prediction. To develop a miRNA as a therapeutic target, it is essential to validate its relationship to the expression of the target protein. Therefore, further studies are necessary to validate the role of miR-384-5p, miR-494, miR-320, miR-129 and miR-326 in the regulation of Bcl-2 and caspase-3 both in vivo and in vitro.

In brief, results from this study showed that transient focal ischemia induces an extensive change in the expression of many cerebral miRNAs. In addition, bioinformatic analysis showed that bcl-2 was the target gene of miR-384-5p and miR-494, and caspase-3 was the target gene of miR-320, miR-129 and miR-326. This suggests that miRNAs may regulate apoptosis of neural cells by regulating apoptotic factors. They thereby participate in the pathological mechanism of cerebral ischemia, and become potential targets for the treatment of ischemic cerebral injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

A randomized, controlled animal experiment.

Time and setting

This experiment was performed between March 2010 and May 2011 at the Department of Pharmacology, Mudanjiang Medical College, China.

Materials

Twenty adult male Sprague-Dawley rats of clean grade, weighing 270–320 g, were obtained from the Institute of Beijing Weitonglihua Experimental Animals, Beijing, China (License No. 2006-0009). Animals were housed at 22 ± 2°C in relative humidity of 50 ± 10% with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and free access to chow and water. The animal care and experimental protocols were in accordance with the Guidance Suggestions for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, issued by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China[36].

Methods

Establishment of rat MCAO models

Focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury was induced in the MCAO group by occlusion of the middle cerebral artery using a previously described method[37,38,39].

In brief, following anesthesia by intraperitoneal injection of 350 mg/kg chloral hydrate, the right common carotid artery, internal carotid artery and external carotid artery were surgically exposed. A 4-0 monofilament nylon suture (Beijing Sunbio Biotech, Beijing, China) with a rounded tip was inserted into the internal carotid artery through the external carotid artery stump and gently advanced to occlude the middle cerebral artery. After 90 minutes of MCAO, the suture was removed to restore blood flow up to 24 hours. Rats in the sham-surgery group were manipulated in the same way, but the middle cerebral artery was not occluded. The rectal temperature was maintained at 37.0 ± 0.5°C with a heating pad throughout the surgical procedure.

Before euthanasia, neurological evaluation was performed using Longa's method[38], by a single investigator, who was blinded to the experimental groups. Neurological findings were scored on a 5-point scale. No neurological deficit = 0, failure to extend left paw fully = 1, circling to left = 2, falling to left = 3, did not walk spontaneously and had depressed levels of consciousness = 4. Following surgery, rats with a neurological score of ≥ 2 were selected for the study, and rats with a score of < 2 were considered to have unsuccessful MCAO.

Microarray analysis of rat brain tissue microRNAs

Four rats that scored 2 in the neurological function test were anesthetized and decapitated 24 hours after MCAO. Three sham-surgery rats served as controls. Total RNA was extracted from the ipsilateral cortex of each rat. Total RNA was extracted from brain tissue using TRIZOL (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and miRNeasy mini kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The A260 nm/A280 nm ratio of RNA solutions was determined using ultraviolet absorbance measurement. The ratio value of each sample was controlled between 1.8–2.1. miRNA was labeled according to the instructions of the miRCURY™. Hy3™. Power labeling kit (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark). 25 μL labeled product and 25 μL 1.5 × hybridization buffer were mixed together and incubated for 2 minutes at 95°C in the 12-Bay Hybridization System (Hybridization System-Nimblegen Systems, Madison, WI, USA), and then left on ice for 2 minutes. The mixture was hybridized overnight at 56°C, with a rotation speed of 2 r/min.

Subsequently, the array was washed sequentially with Wash buffers A, B, C, followed by clean water, centrifuged at 400 r/min for 5 minutes, dried, and photographed using an Axon GenePix 4000B microarray scanner (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). Data were analyzed using GenePix Pro 6.0 software (Axon Instruments). Differentially expressed miRNAs with gene expression > 50% were validated using Volcano Plot filtering (P < 0.05). Data were normalized using median normalization. Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed with average linkage and Euclidean distance metric.

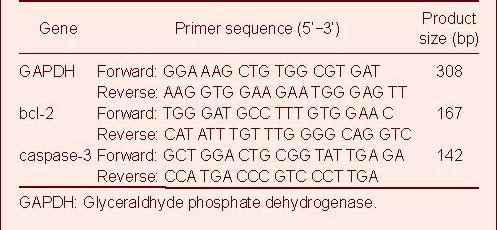

Quantification of mRNA expression by real-time PCR

Real-time PCR[40] was performed to confirm the microarray data. Reverse transcription was performed using the miR qRT-PCR Quantitation Kit (Integrated Biotech Solutions, Shanghai, China) at 16°C for 30 minutes, 42°C for 45 minutes, and 85°C for 10 minutes in a 20 μL reaction system. Primers were synthesized by Integrated Biotech Solutions, Shanghai, China. 2 μL cDNA was added to a 20 μL real-time PCR reaction system. Real-time PCR was conducted at 94°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 20 seconds and 62°C for 40 seconds. The threshold cycle (Ct) method was used to determine the relative quantity of each miRNA. The mRNA levels of bcl-2 and caspase-3 were evaluated in the sham-surgery group and in the MCAO group 24 hours after reperfusion by real-time PCR using the SYBR-Green method[14]. Glyceraldhyde phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal control. PCR primers were synthesized by Invitrogen, Shanghai, China (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primer sequences for real-time PCR quantitative analysis

Western blot analysis of rat brain tissue

Total protein of brain tissue was extracted as previously described[41]. Equal amounts of protein were electrophoresed through a reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel and electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After incubation in blocking buffer (5% non-fat dried milk, phosphate-buffered saline and 0.1% Tween-20) at room temperature for 1 hour, membranes were incubated with mouse anti-rat Bcl-2 monoclonal antibody (1:800; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), rabbit anti-rat caspase-3 polyclonal antibody (1:600; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or rabbit anti-β-actin polyclonal antibody (1:3 000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C. Protein levels were detected with goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (1:2 000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at room temperature for 1 hour and developed with Super ECL Plus detection reagent (Applygen Technologies, Beijing, China). Films were scanned and the intensities of immunoblot bands were quantified by densitometry using image analysis software (Image Master Total Lab version 1.00; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Tokyo, Japan). The band absorbance values were calculated as a ratio of Bcl-2/β-actin or caspase-3/β-actin.

Statistical analysis

All data were statistically processed using SPSS 11.5 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and expressed as mean ± SD. Mean comparisons between two points were performed using two-sample t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Footnotes

Funding: The project was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 30973897; the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province, No. D200978; the Postgraduate Innovative Scientific Research Foundation of Heilongjiang Province, No. YJSCX2011-286HLJ.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Ethical approval: This experiment was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Heilongjiang Province in China.

(Edited by Wang HL, Qi JP/Song LP)

REFERENCES

- 1.Mattson MP, Duan W, Pedersen WA, et al. Neurodegenerative disorders and ischemic brain diseases. Apoptosis. 2001;6(1-2):69–81. doi: 10.1023/a:1009676112184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136(2):215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen K, Rajewsky N. The evolution of gene regulation by transcription factors and microRNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(2):93–103. doi: 10.1038/nrg1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filip A. MiRNA-new mechanisms of gene expression control. Postepy Biochem. 2007;53(4):413–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosik KS. The neuronal microRNA system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(12):911–920. doi: 10.1038/nrn2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redell JB, Liu Y, Dash PK. Traumatic brain injury alters expression of hippocampal microRNAs: potential regulators of multiple pathophysiological processes. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87(6):1435–1448. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, et al. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004;23(20):4051–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wienholds E, Plasterk RH. MicroRNA function in animal development. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(26):5911–5922. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicoloso MS, Calin GA. MicroRNA involvement in brain tumors: from bench to bedside. Brain Pathol. 2008;18(1):122–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hébert SS, Horré K, Nicolaï L, et al. Loss of microRNA cluster miR29a/b-1 in sporadic Alzheimer's disease correlates with increased BACE1/beta-secretase expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(17):6415–6420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710263105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J, Inoue K, Ishii J, et al. A microRNA feedback circuit in midbrain dopamine neurons. Science. 2007;317(5842):1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1140481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhn DE, Nuovo GJ, Martin MM, et al. Human chromosome 21-derived miRNAs are overexpressed in Down syndrome brains and hearts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370(3):473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Beveridge NJ, Tooney PA, Carroll AP, et al. Dysregulation of miRNA 181b in the temporal cortex in schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(8):1156–1168. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dharap A, Bowen K, Place R, et al. Transient focal ischemia induces extensive temporal changes in rat cerebral microRNAome. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29(4):675–687. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeyaseelan K, Lim KY, Armugam A. MicroRNA expression in the blood and brain of rats subjected to transient focal ischemia by middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2008;39(3):959–966. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.500736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu DZ, Tian Y, Ander BP, et al. Brain and blood microRNA expression profiling of ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and kainate seizures. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(1):92–101. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin KJ, Deng Z, Huang H, et al. miR-497 regulates neuronal death in mouse brain after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;38(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soriano MA, Tessier M, Certa U, et al. Parallel gene expression monitoring using oligonucleotide probe arrays of multiple transcripts with an animal model of focal ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20(7):1045–1055. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vemuganti R, Bowen KK, Dhodda VK, et al. Gene expression analysis of spontaneously hypertensive rat cerebral cortex following transient focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurochem. 2002;83(5):1072–1086. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu A, Tang Y, Ran R, et al. Genomics of the periinfarction cortex after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23(7):786–810. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000062340.80057.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du X, Tang Y, Xu H, et al. Genomic profiles for human peripheral blood T cells, B cells, natural killer cells, monocytes, and polymorphonuclear cells: Comparisons to ischemic stroke, migraine, and Tourette syndrome. Genomics. 2006;87(6):693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dharap A, Vemuganti R. Ischemic pre-conditioning alters cerebral microRNAs that are upstream to neuroprotective signaling pathways. J Neurochem. 2010;113(6):1685–1691. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapadia R, Tureyen K, Bowen KK, et al. Decreased brain damage and curtailed inflammation in transcription factor C/EBP-β knockout mice following transient focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurochem. 2006;98(6):1718–1731. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan YP, Sailor KA, Lang BT, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 plays a critical role in neuroblast migration after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(6):1213–1224. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawaguchi M, Drummond JC, Cole DJ, et al. Effect of isoflurane on neuronal apoptosis in rats subjected to focal cerebral ischemia. Anesth Analg. 2004;98(3):798–805. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000105872.76747.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan J. Neuroprotective strategies targeting apoptotic and necrotic cell death for stroke. Apoptosis. 2009;14(4):469–477. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0304-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gustafsson AB, Gottlieb RA. Bcl-2 family members and apoptosis, taken to heart. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292(1):C45–C51. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00229.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Earnshaw WC, Martins LM, Kaufmann SH. Mammalian caspases: structure, activation, substrates and functions during apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:383–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen GM. Caspases: The executioners of apoptosis. Biochem J. 1997;326(Pt 1):1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3260001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Letai A. PharMCAOlogical manipulation of Bcl-2 family members to control cell death. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(10):2648–2655. doi: 10.1172/JCI26250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer U, Schulze-Osthoff K. New approaches and therapeutics targeting apoptosis in disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57(2):187–215. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jovanovic M, Hengartner MO. miRNAs and apoptosis: RNAs to die for. Oncogene. 2006;25(46):6176–6187. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang Y, Zheng J, Sun Y, et al. MicroRNA-1 regulates cardiomyocyte apoptosis by targeting Bcl-2. Int Heart J. 2009;50(3):377–387. doi: 10.1536/ihj.50.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schickel R, Boyerinas B, Park SM, et al. MicroRNAs: key players in the immune system, differentiation, tumorigenesis and cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27(45):5959–5974. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuhn DE, Martin MM, Feldman DS, et al. Experimental validation of miRNA targets. Methods. 2008;44(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China. Guidance Suggestions for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 2006-09-30 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, et al. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20(1):84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zierath D, Hadwin J, Savos A, et al. Anamnestic recall of stroke-related deficits: an animal model. Stroke. 2010;41(11):2653–2660. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calloni RL, Winkler BC, Ricci G, et al. Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats as an experimental model of brain ischemia. Acta Cir Bras. 2010;25(5):428–433. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502010000500008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buller B, Liu XS, Wang XL, et al. miR-21 protects neurons from ischemic death. FEBS J. 2010;277(20):4299–4307. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kao TK, Ou YC, Kuo JS, et al. Neuroprotection by tetramethylpyrazine against ischemic brain injury in rats. Neurochem Int. 2006;48(3):166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]