Abstract

CKD is a risk factor for heart failure, but there is no data on the risk of ESRD and death after recurrent hospitalizations for heart failure. We sought to determine how interim heart failure hospitalizations modify the subsequent risk of ESRD or death before ESRD in patients with CKD. We retrospectively identified 2887 patients with a GFR between 15 and 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 referred between January of 2001 and December of 2008 to a nephrology clinic in Toronto, Canada. We ascertained interim first, second, and third heart failure hospitalizations as well as ESRD and death before ESRD outcomes from administrative data. Over a median follow-up time of 3.01 (interquartile range=1.56–4.99) years, interim heart failure hospitalizations occurred in 359 (12%) patients, whereas 234 (8%) patients developed ESRD, and 499 (17%) patients died before ESRD. Compared with no heart failure hospitalizations, one, two, or three or more heart failure hospitalizations increased the adjusted hazard ratio of ESRD from 4.89 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 3.21 to 7.44) to 10.27 (95% CI, 5.54 to 19.04) to 14.16 (95% CI, 8.07 to 24.83), respectively, and the adjusted hazard ratio death before ESRD from 3.30 (95% CI, 2.55 to 4.27) to 4.20 (95% CI, 2.82 to 6.25) to 6.87 (95% CI, 4.96 to 9.51), respectively. We conclude that recurrent interim heart failure is associated with a stepwise increase in the risk of ESRD and death before ESRD in patients with CKD.

Keywords: CKD, congestive heart failure, ESRD, mortality risk, clinical epidemiology

The 5.7 million American adults who suffer from heart failure (HF) have higher short-term and long-term mortality compared with patients without HF.1–3 Hospitalizations for HF are a significant contributor to health care expenditures.4 Concurrently, 23.5 million Americans have CKD, and the burdens of both HF and CKD are anticipated to rise as the population ages and diabetes and hypertension become increasingly prevalent.5,6 Community-based studies have shown that CKD is an independent risk factor for incident HF,7 which in turn, leads to excess morbidity and mortality.8 HF itself may predispose patients to incident or progressive CKD by way of altered renal hemodynamics9 or comorbid atherosclerotic disease.10

Readmission for HF is common and imposes additional health care costs and reduced quality of life.11 Each subsequent HF hospitalization successively increases the risk of early mortality.12,13 However, these studies excluded patients with advanced CKD and did not examine the risk of kidney failure (ESRD) as an outcome. For clinicians who treat patients with both HF and CKD, knowledge regarding the relative magnitudes of the risks of ESRD and death before ESRD and whether these risks change with successive episodes of HF would help to guide management. Thus, the objective of this study was to determine how first and recurrent interim HF hospitalizations modify the mortality and renal outcomes in a cohort of referred patients followed for CKD.

Results

Study Cohort Characteristics and Unadjusted Event Rates

The 2887 patients with CKD had a mean age of 71 years, a mean GFR of 38 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and a median albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) of 75 mg/g (Table 1). Over a median follow-up of 3.01 years (interquartile range=1.56–4.99), 234 (8%) patients developed ESRD, and 499 (17%) patients died before ESRD. The unadjusted rate per 100 person-years of death before ESRD (5.54; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 5.07 to 6.06) was higher than the rate of ESRD (2.60; 95% CI, 2.27 to 2.96; P<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics at referral

| Characteristics | All Patients (n=2887) | One or More HF Hospitalizations (n=359) | No HF Hospitalizations (n=2528) | No. Missinga |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (yr), mean (SD) | 71 (13) | 77 (9) | 70 (14) | — |

| Men, n (%) | 1625 (56) | 226 (63) | 1399 (55) | — |

| Physical examination variables, mean (SD) | ||||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 136 (21) | 138 (20) | 136 (22) | 230 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 74 (12) | 71 (10) | 74 (12) | 230 |

| Comorbid conditions, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 967 (33) | 186 (52) | 781 (31) | — |

| Hypertension | 1967 (68) | 279 (78) | 1688 (67) | — |

| HF | 582 (20) | 201 (56) | 381 (15) | — |

| Occlusive cardiovascular disease | 1314 (46) | 259 (72) | 1055 (42) | — |

| Any cardiovascular disease | 1496 (52) | 287 (80) | 1209 (48) | — |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 471 (16) | 83 (23) | 388 (15) | — |

| Cancer | 1188 (41) | 156 (43) | 1032 (41) | — |

| Dementia | 170 (6) | 41 (11) | 129 (5) | — |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.732), mean (SD) | 38 (12) | 33 (10) | 38 (12) | 138 |

| ≥45, n (%) | 843 (31) | 48 (15) | 795 (33) | — |

| ≥30 and <45, n (%) | 1109 (40) | 130 (41) | 979 (40) | — |

| <30, n (%) | 797 (29) | 142 (44) | 655 (27) | — |

| Urine ACR (mg/g), median (IQR) | 90 (29–373) | 96 (38–548) | 88 (28–367) | 1479 |

| <30, n (%) | 361 (26) | 33 (21) | 328 (26) | — |

| 30–300, n (%) | 644 (46) | 74 (48) | 570 (45) | — |

| >300, n (%) | 403 (29) | 48 (31) | 355 (28) | — |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl), mean (SD) | 1.84 (0.58) | 1.98 (0.54) | 1.82 (0.58) | 138 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl), mean (SD) | 9.44 (0.63) | 9.38 (0.62) | 9.45 (0.63) | 1106 |

| Serum phosphate (mg/dl), mean (SD) | 3.79 (0.75) | 3.98 (0.74) | 3.76 (0.75) | 1106 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl), mean (SD) | 4.06 (0.45) | 3.94 (0.46) | 4.08 (0.45) | 1106 |

| Serum bicarbonate (mmol/L), mean (SD) | 25.66 (3.44) | 26.07 (3.51) | 25.61 (3.42) | 468 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl), mean (SD) | 12.51 (1.85) | 11.94 (1.76) | 12.59 (1.84) | 403 |

| Serum urea (mg/dl), mean (SD) | 34.66 (0.45) | 42.07 (17.41) | 33.72 (14.75) | 472 |

IQR, interquartile range.

Number of patients for whom data were missing and imputed for the main analysis (— indicates n=0).

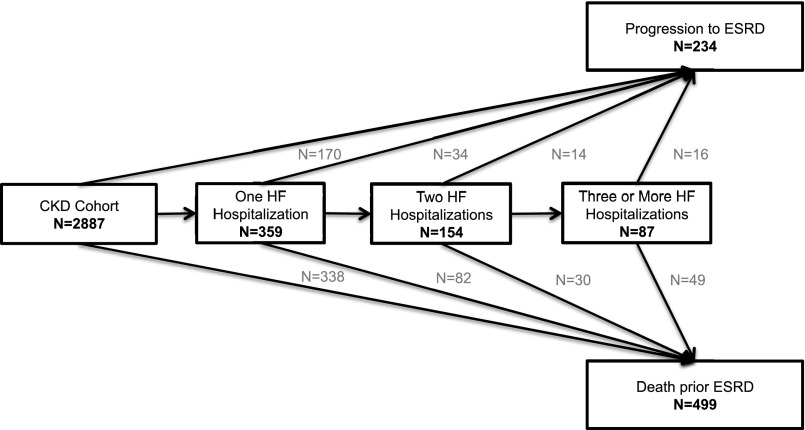

First Interim HF and the Risk of Death and ESRD

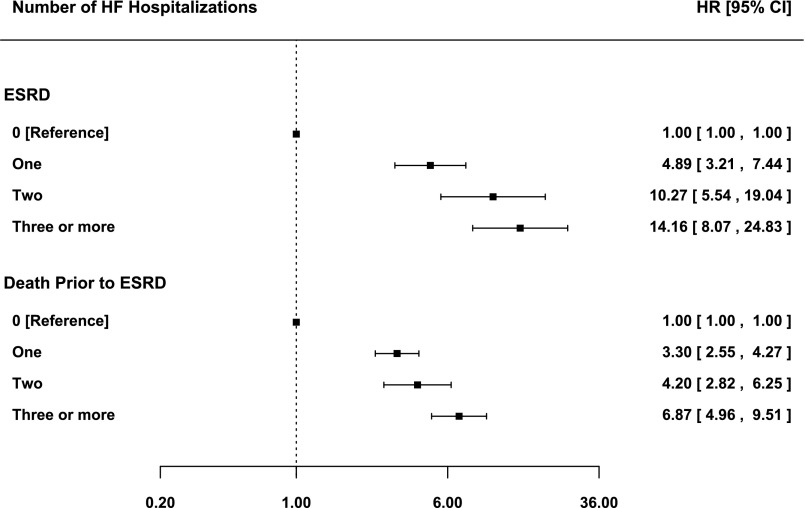

There were 359 (12%) patients with at least one interim HF hospitalization, with a median time to first interim HF hospitalization of 1.31 years (interquartile range=0.44–2.33), which is equivalent to a rate of 4.23/100 patient-years (95% CI, 3.81 to 4.70). Compared with patients who did not or were yet to experience an interim HF hospitalization, we found a 6-fold increase in the adjusted risk of ESRD and a 4-fold increase in the adjusted risk of death before ESRD after the first interim HF hospitalization (Figure 1), with the former being significantly greater than the latter (P=0.03). We did not observe a statistically significant difference in risks of either ESRD or death before ESRD when the first interim HF hospitalization was partitioned into primary HF versus secondary HF hospitalizations (P=0.07 and P=0.08, respectively). The risks of ESRD and death before ESRD after the first interim HF hospitalization also did not differ in patients with a history of HF before referral versus patients with no history of HF before referral (interaction P value=0.75 for ESRD and P value=0.12 for death prior to ESRD). The risks of ESRD and death before ESRD were both highest in the first 3 months after admission for interim HF and declined thereafter (Figure 2). At 3 and 6 months after the interim HF hospitalization, the risk of ESRD was higher than the risk of death before ESRD (P=0.001 and P=0.008 for difference, respectively). After 6 months, the risks of both outcomes were similar, and by 18 months, they remained 2- to 3-fold higher than the risks in patients who did not or were yet to experience an interim HF hospitalization.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted rate and adjusted risk of outcomes after the first interim HF hospitalizations. Rates are per 100 person-years (P-Yrs). Forrest plots depict adjusted HRs and 95% CIs of each outcome after the first interim HF hospitalizations

Figure 2.

Adjusted risk of outcomes by time after the first interim HF hospitalizations. Plots depict adjusted HRs and 95% CIs of each outcome over prespecified time intervals after the occurrence of the first interim HF hospitalization.

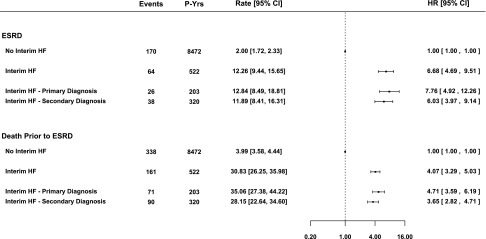

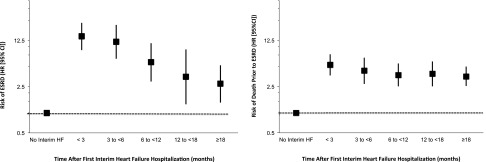

Recurrent Interim HF and the Risk of Death and ESRD

In total, 154 (5%) and 87 (3%) patients experienced two and three or more interim HF hospitalizations, respectively (Figure 3). Additionally, at 1, 3, and 12 months after the first interim HF hospitalization, 8%, 20%, and 34% of patients had experienced a second HF hospitalization, respectively. After adjusting for recurrent interim HF hospitalizations, the risks of ESRD and death before ESRD after the first interim HF hospitalization were attenuated but remained significantly elevated. Furthermore, compared with patients who did not or were yet to experience an interim HF hospitalization, one, two, and three or more interim HF hospitalizations were associated with a stepwise increase in the adjusted relative risk of ESRD and death before ESRD, with hazard ratios (HRs) ranging from 4.89 (95% CI, 3.21 to 7.44) to 14.16 (95% CI, 8.07 to 24.83) (P<0.001 for linear trend) and from 3.30 (95% CI, 2.55 to 4.27) to 6.87 (95% CI, 4.96 to 9.51) (P<0.001 for linear trend), respectively (Figure 4). There was no significant difference between the HRs for ESRD and death before ESRD after the first (P=0.16) interim HF hospitalization, whereas ESRD risk was greater than death before ESRD risk after the second (P=0.03) and third (P=0.04) interim HF hospitalizations.

Figure 3.

Number of recurrent HF hospitalizations. The number of patients experiencing each outcome after the first and recurrent interim HF hospitalizations.

Figure 4.

Adjusted risk of outcomes after recurrent interim HF hospitalizations. Forrest plots depict adjusted HRs and 95% CIs of each outcome after the first and recurrent interim HF hospitalizations.

Sensitivity Analyses

When using age as the timescale, excluding patients with a missing GFR, repeating the analysis using four alternative definitions of CKD, and adjusting for myocardial infarction and stroke events, the results remained comparable (Supplemental Table 3). Furthermore, results were similar to the main analysis when death, either before or after ESRD, was the outcome of interest and we accounted for additional interim HF hospitalizations occurring in patients who developed ESRD during the follow-up period (Supplemental Figure 2). Recurrent HF admissions were associated with a marked increase in the risk of myocardial infarction but not stroke before ESRD (Supplemental Figure 3).

Discussion

In a cohort of patients with CKD (GFR=15–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) referred for nephrology care, we observed that interim HF hospitalizations were common and associated with successive 4-, 10-, and 14-fold increases in the likelihood of ESRD, 23-, 18-, and 29-fold increases in the likelihood of myocardial infarction, and 3-, 4-, and 6- fold increases in the likelihood of death before ESRD with each subsequent hospitalization, respectively. The absolute rate of death before ESRD was larger than the rate of ESRD in patients with interim HF hospitalizations compared with those never having experienced or yet to experience interim HF hospitalizations. The risk of ESRD was highest in the first 3–6 months after an interim HF hospitalization and attenuated thereafter, but it remained elevated at two to three times the baseline risk past the first year. For death before or after ESRD, we observed a stepwise increase in risk after recurrent interim HF hospitalizations that was comparable with other published analyses.12

Prior studies of recurrent HF hospitalizations in chronic HF cohorts have not directly addressed the added complexity of patients who also have CKD. The Enhanced Feedback for Effective Cardiac Treatment (EFFECT) Study in Ontario, Canada showed a stepwise increase in mortality risk after recurrent HF hospitalizations.12 Although the presence of CKD was considered, the study relied on administrative case definitions, which may have limited sensitivity for the diagnosis of CKD. Investigators from the Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) program followed patients with chronic HF with a serum creatinine<265 μmol/L for nonfatal HF hospitalizations.13 They found a stepwise increase in mortality risk associated with nonfatal HF hospitalizations.13 However, baseline CKD prevalence was not reported, and neither GFR nor ACR was used as an adjustment factor. On the basis of substudies of CHARM, the majority of participants had a baseline GFR of 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or higher.14 Furthermore, measures of albuminuria were available in 30% of North American patients, of whom 58% had normal values.15 Thus, it may be difficult to generalize data from the CHARM or the EFFECT studies regarding the effect of recurrent HF hospitalizations on patients with lower GFR and/or albuminuria.

The mechanisms underlying the observations in this study are uncertain. However, CKD may lead to impaired salt and water excretion, resulting in intravascular overload. The latter may alter hemodynamics and lead to unfavorable loading conditions in the setting of preexisting systolic or diastolic dysfunction, which in turn, may lead to kidney congestion or decreased kidney perfusion, further compromising kidney function.16 In a prospective echocardiography study of patients with CKD, depressed baseline left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was independently associated with progressive CKD.17 Moreover, left atrial enlargement, an echocardiographic surrogate for cardiac pressure and/or volume overload, independently predicted progressive CKD, even when patients with an LVEF<50% were excluded. In a substudy of the Trial to Reduce Cardiovascular Events with Aranesp Therapy,18 an elevated N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide, a biochemical surrogate for cardiac pressure and/or volume overload, stratified death and ESRD risk in patients with detectable and undetectable Troponin T. Lastly, a recent prospective study in patients with stages 4 and 5 CKD showed an association with moderate and severe volume overload with progressive CKD and ESRD.19 Our findings suggest that HF, the clinical entity that encompasses left ventricular dysfunction, myocardial injury, and strain, and volume overload independently increase ESRD and mortality risk in patients with CKD.

Our findings have clinical and research implications. Vigilance is needed in caring for patients with CKD to recognize the effect of HF admissions, because each successive HF admission is associated with an increase in both ESRD and mortality risk. Readmission risk for HF is lower in patients with HF prescribed disease-modifying pharmacotherapies in clinical trial and registry data.20,21 Furthermore, early physician follow-up after hospitalization for acute HF is associated with lower readmission rates22,23 and mortality23 at 30 days. Thus, additional investigation is warranted to determine whether prevention of incident and recurrent events through pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions may improve mortality and cardiac and renal outcomes in patients with CKD.

Our analysis has several strengths. We modeled the effects of interim HF on two clinically relevant and mutually exclusive outcomes in patients with CKD. The use of diagnostic codes for HF hospitalizations that have been previously validated increases the generalizability and reduces ascertainment bias (Supplemental Table 2). The primary end point of ESRD, defined as the initiation of RRT rather than a drop of GFR below a given threshold, has the advantage of being the most clinically relevant outcome. Moreover, the low emigration rate in Ontario of <1.0%/yr24 and the province-wide outcome ascertainment minimized ascertainment bias in our cohort.

Our analysis has several limitations. HF admissions were on the basis of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) coding rather than direct chart audit. However, administrative codes used for HF have been shown to have a high positive predictive value in validation studies.25–27 Prognostic markers in patients with HF such as LVEF or evidence-based cardioprotective medication use, which may have attenuated the reported effect estimates, were not available. In the CHARM study, the association between renal function and mortality was similar across subgroups of patients with LVEF<50% and ≥50%.14 Moreover, the EFFECT investigators found that the relationship between mortality risk and recurrent HF events remained significant after adjusting for cardioprotective medications.12 Although some patients had measured variables after the origin, our previous work with the kidney risk failure equation derived in the same population showed excellent internal28 and external29 validity using the same methodology. The CKD Prognosis Consortium,30 to which the Sunnybrook Nephrology Electronic Medical Record (EMR) has contributed, uses a similar strategy to capture baseline GFR around a window surrounding the origin.

In conclusion, we report, in a large well described cohort of patients with CKD, that first, second, and third interim HF hospitalizations confer 4-, 10-, and 14-fold increases in ESRD risk and 3-, 4-, and 6-fold increases in mortality risk before ESRD compared with patients never experiencing or yet to experience an HF hospitalization. Additional prospective investigations in this high-risk population are needed to determine if primary and secondary preventative measures may attenuate the risk of these outcomes.

Concise Methods

Study Cohort

The Sunnybrook Nephrology EMR database has tracked all outpatient referrals to the nephrology clinic at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (SHSC) in the North York region of Toronto, Ontario since its inception in April of 2001 (n=6255).28 Patients referred before January 1, 2001, in whom follow-up data were not available, were excluded (n=603). Patients with a GFR<15 or >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at the time of referral31 (n=216 and n=2545, respectively) and HF hospitalizations or ESRD occurring before the date first seen in the clinic were excluded (n=14), yielding a primary analysis cohort of 2887 patients with G3–G4 CKD by the new Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes classification.32 (Supplemental Figure 1).

Definition and Ascertainment of Predictor and Outcome Variables

The origin for time-to-event analyses was defined as the date of the first nephrology clinic visit. The primary exposure variable was the first interim HF hospitalization after the origin in which there was an administrative code for HF as either a primary or secondary diagnosis. Second and third recurrent interim HF hospitalizations were ascertained similarly along with interim myocardial infarction and stroke hospitalizations. Interim hospitalizations were ascertained through linkage with the Canadian Institute of Health Information Discharge Abstract Database (CIHI DAD), which contains information on hospitalizations within Ontario, including admission and discharge dates and diagnostic codes for up to eight diagnoses from the ICD 9th revision in 2001 and 25 diagnoses from the ICD 10th revision from 2002 to 2008 (Supplemental Table 2).

Baseline predictor variables were obtained from the SHSC Nephrology EMR and included demographic variables (age and sex), physical examination data (BP), and presence of comorbid conditions (diabetes, hypertension, HF, and previous occlusive cardiovascular disease). Previous occlusive cardiovascular disease (cerebral, coronary, or peripheral) and previous HF were defined as hospitalizations or outpatient diagnoses that occurred before the origin. Additional baseline cancer (ICD-9: 140–239 and ICD-10: C00–C97 and D10–D48), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ICD-9: 490–493 and 496 and ICD-10: J20 and J40 –J45), and dementia (ICD-9: 290 and ICD-10: F00–F03) were ascertained from CIHI DAD.12 Baseline laboratory variables, including serum creatinine, calcium, phosphate, albumin, bicarbonate, and hemoglobin, were defined as the first result closest to and within 365 days of the origin and at least 30 days before the first interim HF hospitalization when applicable. Baseline serum creatinine measurements were provided by the Sunnybrook clinical laboratory as well as several community laboratories (Supplemental Table 2). GFR was estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology 2009 creatinine equation.6 Albuminuria was quantified by direct measurement of the urine ACR or use of a formula derived from the Irbesartan in the Diabetic Nephropathy Trial study, whereby 24-hour urinary protein excretion was transformed to an ACR.33 Except for ACR, baseline variables had <25% missing data. Missing data for all variables were imputed using the multiple imputation technique34 with 20 imputations on the basis of PROC MI in SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

The outcomes of interest included ESRD and death before ESRD. ESRD was defined as the need for dialysis or preemptive renal transplantation and ascertained through linkage to the Ontario Ministry of Health Physician Claims Database, which contains all records of physician billing activity in Ontario. We used the date of the first fee claim for dialysis or renal transplant enumerated in this database as the date of ESRD for our analysis. Death before ESRD was ascertained from the Ontario Registered Persons Database, which contains vital statistics on all residents of Ontario eligible for the Ontario Health Insurance Plan.35

Statistical Analyses

Laboratory variables and physical examination characteristics were evaluated as linear predictors except for ACR, which was log-transformed. We developed Cox proportional hazard models for ESRD and death before ESRD outcomes and analyzed the cause-specific HRs associated with time-dependent covariates (interim HF hospitalizations) while adjusting for time-independent covariates (age, sex, BP, history of diabetes, hypertension, occlusive cardiovascular disease, HF, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and dementia as well as laboratory data, such as eGFR, ACR, calcium, phosphate, bicarbonate, urea, albumin, and hemoglobin).36 We tested for an interaction between the first interim HF hospitalization and a baseline history of HF before referral. At the origin, patients were assigned the value zero for a time-dependent covariate that incremented by one unit, up to a maximum of three, for each interim HF hospitalization. Patients could accrue changes to the time-dependent covariate until any of the outcomes of interest occurred or the subject was censored. We tested for a difference between the cause-specific HRs associated with interim HF hospitalizations and the two outcomes by introducing an interaction term between the time-dependent covariates and the type of outcome in a stratified Cox model.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. Age as the timescale was used rather than time on study to rule out additional confounding by age at the time of referral that was not sufficiently accounted for by including age as a baseline covariate in the proportional hazards model.37 The analysis was repeated after excluding patients in whom GFR was imputed (n=2749) and four previously published alternative definitions for CKD were used38: (1) GFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or ACR≥30 mg/g (G3–G4 or A2–A3; n=4719), (2) GFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or ACR≥300 mg/g (G3–G4 or A3; n=3275), (3) GFR<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (G3B–G4; n=1980), and (4) GFR<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or ACR≥300 mg/g (G3B–G4 or A3; n=2498) (Supplemental Figure 1). We also adjusted for interim myocardial infarction and stroke hospitalizations to rule out residual confounding. We verified that one, two, or three or more recurrent HF hospitalizations were associated with death either before or after ESRD as the outcome of interest. In the latter sensitivity analysis, the effect of reaching ESRD on mortality risk was also treated as a binary time-dependent covariate. Lastly, in a supplemental analysis, we examined the effect of one, two, or three or more HF admissions with the risk of subsequent myocardial infarction and stroke events that occurred before ESRD.

For covariates where there was evidence of nonproportionality, the time-average effect was reported.39 Except for data imputation (above), statistical analyses were carried out at a two-sided significance level of P<0.05 using open source R v3.02 software. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at SHSC, and a waiver of consent was granted given its retrospective nature.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2014030253/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee : Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 125: e2–e220, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg RJ, Ciampa J, Lessard D, Meyer TE, Spencer FA: Long-term survival after heart failure: A contemporary population-based perspective. Arch Intern Med 167: 490–496, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chin MH, Goldman L: Correlates of early hospital readmission or death in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 79: 1640–1644, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braunstein JB, Anderson GF, Gerstenblith G, Weller W, Niefeld M, Herbert R, Wu AW: Noncardiac comorbidity increases preventable hospitalizations and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 42: 1226–1233, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grams ME, Juraschek SP, Selvin E, Foster MC, Inker LA, Eckfeldt JH, Levey AS, Coresh J: Trends in the prevalence of reduced GFR in the United States: A comparison of creatinine- and cystatin C-based estimates. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 253–260, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J, CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kottgen A, Russell SD, Loehr LR, Crainiceanu CM, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Chambless LE, Coresh J: Reduced kidney function as a risk factor for incident heart failure: The atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1307–1315, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Amin MG, Stark PC, MacLeod B, Griffith JL, Salem DN, Levey AS, Sarnak MJ: Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: A pooled analysis of community-based studies. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1307–1315, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McClellan WM, Langston RD, Presley R: Medicare patients with cardiovascular disease have a high prevalence of chronic kidney disease and a high rate of progression to end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1912–1919, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalra PA, Guo H, Kausz AT, Gilbertson DT, Liu J, Chen SC, Ishani A, Collins AJ, Foley RN: Atherosclerotic renovascular disease in United States patients aged 67 years or older: Risk factors, revascularization, and prognosis. Kidney Int 68: 293–301, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross JS, Chen J, Lin Z, Bueno H, Curtis JP, Keenan PS, Normand SL, Schreiner G, Spertus JA, Vidán MT, Wang Y, Wang Y, Krumholz HM: Recent national trends in readmission rates after heart failure hospitalization. Circ Heart Fail 3: 97–103, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DS, Austin PC, Stukel TA, Alter DA, Chong A, Parker JD, Tu JV: “Dose-dependent” impact of recurrent cardiac events on mortality in patients with heart failure. Am J Med 122: 162–169, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon SD, Dobson J, Pocock S, Skali H, McMurray JJ, Granger CB, Yusuf S, Swedberg K, Young JB, Michelson EL, Pfeffer MA, Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) Investigators : Influence of nonfatal hospitalization for heart failure on subsequent mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 116: 1482–1487, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillege HL, Nitsch D, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, Granger CB, Michelson EL, Ostergren J, Cornel JH, de Zeeuw D, Pocock S, van Veldhuisen DJ, Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) Investigators : Renal function as a predictor of outcome in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure. Circulation 113: 671–678, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson CE, Solomon SD, Gerstein HC, Zetterstrand S, Olofsson B, Michelson EL, Granger CB, Swedberg K, Pfeffer MA, Yusuf S, McMurray JJ, CHARM Investigators and Committees : Albuminuria in chronic heart failure: Prevalence and prognostic importance. Lancet 374: 543–550, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.F Gnanaraj J, von Haehling S, Anker SD, Raj DS, Radhakrishnan J: The relevance of congestion in the cardio-renal syndrome. Kidney Int 83: 384–391, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen SC, Su HM, Hung CC, Chang JM, Liu WC, Tsai JC, Lin MY, Hwang SJ, Chen HC: Echocardiographic parameters are independently associated with rate of renal function decline and progression to dialysis in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 2750–2758, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desai AS, Toto R, Jarolim P, Uno H, Eckardt KU, Kewalramani R, Levey AS, Lewis EF, McMurray JJ, Parving HH, Solomon SD, Pfeffer MA: Association between cardiac biomarkers and the development of ESRD in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, anemia, and CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 58: 717–728, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai YC, Tsai JC, Chen SC, Chiu YW, Hwang SJ, Hung CC, Chen TH, Kuo MC, Chen HC: Association of fluid overload with kidney disease progression in advanced CKD: A prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 68–75, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaduganathan M, Fonarow GC, Gheorghiade M: Drug therapy to reduce early readmission risk in heart failure: Ready for prime time? JACC Heart Fail 1: 361–364, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai AS, Stevenson LW: Rehospitalization for heart failure: Predict or prevent? Circulation 126: 501–506, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, Hammill BG, Heidenreich PA, Yancy CW, Peterson ED, Curtis LH: Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA 303: 1716–1722, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAlister FA, Youngson E, Bakal JA, Kaul P, Ezekowitz J, van Walraven C: Impact of physician continuity on death or urgent readmission after discharge among patients with heart failure. CMAJ 185: E681–E689, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ontario Ministry of Finance: Ontario Population Projections 2011–2036: Ontario and Its 49 Census Divisions, 2012. Available at: http://www.fin.gov.onca/en/economy/demographics/projections. Accessed January 17, 2014

- 25.Quan H, Parsons GA, Ghali WA: Validity of information on comorbidity derived rom ICD-9-CCM administrative data. Med Care 40: 675–685, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA: Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 45: 613–619, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henderson T, Shepheard J, Sundararajan V: Quality of diagnosis and procedure coding in ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 44: 1011–1019, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, Tighiouart H, Djurdjev O, Naimark D, Levin A, Levey AS: A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA 305: 1553–1559, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peeters MJ, van Zuilen AD, van den Brand JA, Bots ML, Blankestijn PJ, Wetzels JF, MASTERPLAN Study Group : Validation of the kidney failure risk equation in European CKD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 1773–1779, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, Gansevoort RT, Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: A collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 375: 2073–2081, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sud M, Tangri N, Levin A, Pintilie M, Levey AS, Naimark DM: CKD stage at nephrology referral and factors influencing the risks of ESRD and death. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 928–936, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin A, Stevens PE, Bilous RW, Coresh J, De Francisco AL, De Jong PE, Griffith KE, Hemmelgarn BR, Iseki K, Lamb EJ, Levey AS, Riella MC, Shlipak MG, Wang H, White CT, Winearls CG: KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Chapter 1: Definition and classification of CKD. Kidney Int Suppl 3: 19–62, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parving HH, Lehnert H, Bröchner-Mortensen J, Gomis R, Andersen S, Arner P, Irbesartan in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Microalbuminuria Study Group : The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 345: 870–878, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donders AR, van der Heijden GJ, Stijnen T, Moons KG: Review: A gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. J Clin Epidemiol 59: 1087–1091, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iron K, Zagorski B, Sykora K, Manuel D: Living and Dying in Ontario: An Opportunity for Improved Health Information. ICES Investigative Report, Toronto, CA, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolkewitz M, Vonberg RP, Grundmann H, Beyersmann J, Gastmeier P, Bärwolff S, Geffers C, Behnke M, Rüden H, Schumacher M: Risk factors for the development of nosocomial pneumonia and mortality on intensive care units: Application of competing risks models. Crit Care 12: R44, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thiébaut AC, Bénichou J: Choice of time-scale in Cox’s model analysis of epidemiologic cohort data: A simulation study. Stat Med 23: 3803–3820, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A, Manns BJ, Klarenbach S, Pannu N, James MT, Hemmelgarn BR, Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Risk of coronary events in people with chronic kidney disease compared with those with diabetes: A population-level cohort study. Lancet 380: 807–814, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Latouche A, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, Labopin M, Fine JP: A competing risks analysis should report results on all cause-specific hazards and cumulative incidence functions. J Clin Epidemiol 66: 648–653, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.