Abstract

Background:

About 79% of the pregnant women experience sleep disorders and 70% of pregnant women experience some symptoms of the depression. Physiologic, hormonal, and physical changes of pregnancy can predispose mothers to depression these disorders before, during, and after childbirth and might be aggravated by neglecting health behavior. Health behavior education might be useful for the management of depression in pregnant women.

Objectives:

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of sleep health behavioral education on the improvement of depression in pregnant women with sleep disorders.

Patients and Methods:

This study was a randomized clinical trial, performed on 96 pregnant women with sleep disorder diagnosed according to the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Tools for data collection included demographic questionnaire and Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI). Easy and accessible sampling was done. Participants were randomly (simple) allocated to intervention and control groups. In intervention group, sleep health behavior education was presented during a four-hour session held in weeks 22, 23, 24, and 25; then the patients were followed up to fill out the BDIQ in follow-up session at weeks 29 and 33 of pregnancy. The control group received no intervention and only received routine prenatal care. The results were assessed by Chi-square tests, independent-samples t-test, and Fischer’s exact-test by SPSS 16.

Results:

A statistically significant change was reported in the severity of depression in pregnant women with sleep disorders in the intervention group in comparison to the control group at weeks 29 (P < 0.000) and 33 (P < 0.00).

Conclusions:

Sleep health behavioral education improves depression in pregnant women who are experiencing insomnia. Findings from this study add support to the reported effectiveness of sleep health behavioral education in the prenatal care and clinical management of insomnia in pregnancy.

Keywords: Sleep, Education, Depression, Pregnant Women, Sleep Disorder

1. Background

Pregnancy is the most sensitive and enjoyable event in a woman’s life (1) that can affect sleep patterns, ability to perform daily living tasks, and quality of life due to systemic changes caused by hormonal, emotional, mental, and physical factors (2-4) Changes in sleep patterns during pregnancy might range from 13% to 80% in the first trimester and from 66% to 97% in the third trimester (5). According to the National Sleep (2007), 79% of the pregnant women experience some form of sleep disorder. More than 72% of pregnant women will experience frequent awakening during night (6). Changes in sleep patterns leads to daily dysfunction, fatigue, loss of family welfare, increased accidents and as consequently, reduced quality of life (7). In addition, insomnia-induced reduction in the psychologic relaxation leads to increased anxiety and fear of childcare and accepting maternal role. In this regard, a review of studies on sleep disorders during pregnancy represents an increased risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and increasing challenges of pregnancy; it is also associated with prolonged labor, using delivery instruments, cesarean, and depression during pregnancy and after delivery. In some cases, it might cause postpartum blues, negative effect on families and indirectly on society, and an economic burden to society (7, 8). According to conducted studies, the poor quality of sleep in the second trimester of pregnancy is directly related to depressive symptoms in late pregnancy (9). Depression during pregnancy is prevalent as 70% of pregnant women have some symptoms of depression (10, 11). In several studies, 30.6%, 45.7%, and 57% of women had experienced symptoms of depression during pregnancy (12, 13). According to previous studies, the prevalence of depressive symptoms in pregnancy ranges from 8% to 51% (14, 15). Depression is one the most common psychiatric and mood disorders. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depression is the fourth urgent health problem in the world (16); moreover, depression after delivery is associated with prenatal depression, The most important risk factor and predictor for depressed mood during post-partum was prenatal depression and 50% of women with depression during pregnancy experienced depression after delivery (17). Depression leads to complications in the mother and neonate after delivery and is associated with birth of premature, low birth weight infants. Poor health behaviors include substance use (cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs), not seeking prenatal care, and preeclampsia (18, 19). Newborns would experience restlessness, excessive crying, and sleep disturbance during infancy (20). In the past, it was thought that pregnancy prevent and protect against depression, while studies suggest that not only the depression in the third trimester has high prevalence, but neglecting sleep disorder and considering it as a normal part of pregnancy can affect maternal mental and physical health and might lead to mood disorders.

2. Objectives

Efforts for reducing maternal mortality and morbidity in pregnancy to extend prenatal care and delivery have led to favorable maternal and childhood health outcomes. Due to the limited research in this area, giving priority to the health of pregnant women by the health services is one of the millennium development goals. Early detection and following mother’s depression during pregnancy is important. Thus, the researchers decided to study this field in the hope of being able to increase the protection of women during pregnancy. This could be a step towards the realization of their motto "Healthy mother and healthy child".

3. Patients and Methods

In this randomized clinical trial, 96 pregnant women with insomnia or poor sleep quality (according to the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI]) who were referred to two health-elected city center shuttle were enrolled after obtaining informed consent. The participants were selected by simple random allocation (the table of random numbers) for receiving prenatal care in Maku City, West Azerbaijan, Iran, from June through November 2012. Inclusion criteria were being Iranian, educated, and gestational age of 16 to 20 weeks according to the first day of the last menstrual period and ultrasound during the first trimester of pregnancy. Those with medical or mental illnesses and drugs, alcohol, sleeping drugs, and hormones use were excluded. Elimination criteria were subjects withdrew from the study, the occurrence of a traumatic event or loss during the study, insignificant change in unpredictable conditions such as sleep, travel, working shifts, and diet, and taking any additional medication during the study. This study was a double-blind study; participants were not informed of the intervention, enrollment, and assigned groups by researcher. Those who administered the interventions and assessed outcomes were blinded to group assignment. Used tools were forms of basic characteristics, PSQI, and Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI). Basic characteristic questionnaire included data on age, education, occupation, parity, gestational age, socioeconomic status, body mass index, interval from previous pregnancy, previous delivery, desire for current pregnancy, smoking, fetal sex satisfaction of pregnant woman and his wife, history of fetal malformation in previous pregnancy, and marital status. Sampling was continuous, the first two-part questionnaire included demographic data and PSQI, which were completed by the pregnant women in a quiet room. After review of the questionnaire, women who scored ≥ 5 according to PSQI and ≥ 11 according to BDI were identified as experiencing insomnia or poor quality of sleep. Then the participants were randomly allocated into two groups of 48: control and intervention. The participants with the symptom of severe depression (score > 35) were referred to a physician. In the intervention group, women were trained on sleep hygiene behaviors education in four groups of 12 through lecture with slides and a provided instructional booklet. The health behavior education was educated in one hour at four sessions with one-week interval, started at week 22 and ended at week 25. Different content at each session include:

The First week: educating about the feature of normal sleep, stages of sleep and duration of stages, total sleep time, and sleep alternation (physical, psychologic, and hormonal) in pregnancy and their causes.

The Second week: providing solution of physical alternation in pregnancy that disturbed sleep and pregnant women’ common complications including vomiting, headache, oversleep-fatigue, heartburn, backache, foot spasm, flatulence, constipation, urgency, no daily activity because of fear the losing of pregnancy, and stress.

The third week: arranging a good sleep environment and habits. Participants were taught that room temperature and sounds should be optimized for relaxation (21, 22). A quiet sleep environment was achieved by putting up heavy curtains, maintaining the humidity in the 60% to 70%, selecting comfortable mattresses and bedding, and encouraging participants to lie on their side to enhance feelings of safety and relaxation. Good sleep habits were cultivated, including regular bed/wake-up times, avoiding napping in bed, reducing exposure to light, which causes the release of melatonin and rising body temperature, reducing the time required to fall asleep, and increasing sleep duration, to improve sleep quality. If participants were unable to fall asleep after 30 minutes in bed, they were requested to leave the bedroom and read a book or watch TV until they felt sleepy. Participants were also asked to get up at a regular time, even if they did not have enough sleep the night before (23, 24), reducing emotional stress, which would limits their ability to relax emotionally, affect sleep quality, and alter hormonal balances (25).

The fourth week: controlling diet, alcohol consumption, and tobacco use. We gave instruction on the proper intake of calcium and magnesium in the daily diet and advised that drinking a glass of warm milk with sugar would help to have a good night’s sleep. Avoidance of eating gas-producing food or drinking a large volume of water before going to bed can reduce bloating/decrease urination during the night, both of which affect sleep quality (24, 25). Alcohol should also be avoided before bedtime (23). Moreover, caffeinated drinks such as tea or coffee should be consumed only in small quantities during the four to six hours before bedtime. Caffeine stimulates the central nervous system, increases heart rate, and excites brain functions, all of which reduce sleepiness (26) and exercising regularly. We provided information of the beneficial effects of Walking regular on sleep quality and its related factors. Regular exercise encourages the body to release endorphins, which promote sleep, relieve depression, and relax muscles. Exercise in the early evening can promote health, regulate physiologic and psychologic stress, and improve quality of sleep (23, 24). Exercise conducted in the afternoon or two hours before bedtime was would have the greatest positive effect on sleep quality (27). The control group received no intervention. Only the responsible mid wife for prenatal care was informed of sleep disorders and depression to give up their routine care for them. The sleep quality and depression were checked and there were no differences in that regard two groups (sleep quality: P < 0.566 and depression: P < 0.363).

The first and the second follow-up sessions were held to complete BDI at weeks 29 and 33 of pregnancy to evaluate the effect of training. This study Excluded 12 women; six in control group due to no desire to continue study (three women), preterm labor (two women), and migration to other cities (one woman); and six in intervention group due to no desire to continue study (two women), preterm labor (one woman), migration to other cities (two women), and abortion (one woman).

The PSQI is a retrospective self-report questionnaire that measures sleeping patterns and sleep disturbances that existed during the previous month. The PSQI yields a global score ranging from zero to 21, with higher scores indicating worse sleep quality. The PSQI had strong test-retest reliability, and using a cutoff score of five, the measure demonstrated a sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5% in distinguishing people with insomnia (28). The overall reliability coefficient of the Chinese version PSQI was previously estimated at 0.85 (29). A test-retest reliability (r) of 0.74 over one month was also found for PSQI (30). The 19 questions of PSQI assess the sleep quality in the seven “component” areas: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. The sum of scores for these seven components yields one global score. Individuals with PSQI scores < 5 were categorized as good sleepers, and those with scores ≥ 5 were classified as poor sleepers. The PSQI validity and reliability were determined in two studies in Iran. Malekzadegan et al. determined PSQI validity by content validity and reliability via the test-retest method (31). Hossein Abadi and et al. reported a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 87% for PSQI (32). To determine validity for this study, the PSQI was given to 13 faculty members of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, School of Nursing, and necessary reforms were made. Moreover, we used test-retest to determine the reliability. Briefly, it was given to 15 eligible pregnant women and Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated after ten days that revealed reliability of 82%. The sixth item of PSQI is devoted to the use of sleep medications in pregnancy while the using sleep medication was an exclusion criteria in this study; hence, this dimension of the instrument was not analyzed considered zero in final score calculation. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the validated and reliable 13-item short-form BDI that highly correlates with the long form (33, 34) The long-form BDI has been validated for use in pregnant women (10). BDI contains 21 questions, score of each question ranges from zero to three with the total score of the scale ranging from zero to 63. The total scores are interpreted as follows: 1-10, normal; 11-20, mild depression; 21-30, moderate depression; and ≥ 31, severe depression. BDI is a standard questionnaire that its reliability and validity have been verified in several studies in Iran. The data were analyzed using SPSS 16 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, the United States). Descriptive statistics including means and standard deviations were calculated for all the variables. Independent-samples t-tests, Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact-test, and repeated measure analysis were used to compare the effect of health behavior education on the quality of sleep in study groups. The Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, approved the study and all participants gave their informed consent.

4. Results

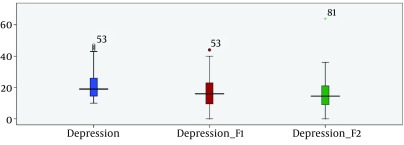

The characteristics and sociodemographic data of the 84 participants are summarized in Tables 1. Two groups were matched perfectly in basic characteristics. According to Table 2, components of sleep quality scores including subjective sleep quality (P < 0.246), sleep latency (P < 0.732), sleep duration (P < 0.474), habitual sleep efficiency (P < 0.288), sleep disturbances (P < 0.583), and daytime dysfunction (P < 0.130) were quite homogeneous between study groups. The comparison of depression measures before intervention and at one month (week 29), and two months (week 33) of intervention in the intervention and control groups are shown in Tables 3 and 4 Figure 1. The depression scores before intervention in the intervention group and control group (P < 0.363) were perfectly homogeneous. Depression scores at one month (P < 0.000) and at two month (P < 0.000) after intervention were significantly different between two groups and the mean of depression score had decreased after interventions.

Table 1. Demographic Status of Pregnant Women Living in Maku Township Who Participated in the Study a, b, c.

| Groups | Intervention | Control | P Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother age, y | 27.26 ± 5.07 | 27.21 ± 5.80 | 0.968 |

| 20-25 | 17 (40.5) | 21 (50.1) | |

| 26-30 | 14 (33.3) | 8 (18) | |

| 31-35 | 8 (19) | 10 (23.8) | |

| 36-40 | 3 (7.1) | 3 (7.1) | |

| Mother’s education | 0.404 | ||

| Primary | 16 (38.1) | 19 (45.2) | |

| Secondary | 13 (31) | 9 (21.4) | |

| Diploma | 9 (21.4) | 6 (14.3) | |

| Collegiate | 4 (9.5) | 8 (19) | |

| Mother’s occupation | 0.693 | ||

| Housekeeper | 39 (92.9) | 35 (83.3) | |

| Worker | 1 (2.4) | 0 | |

| Employee | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.8) | |

| Student | 1 (2.4) | 4 (9.5) | |

| Retired | 0 | 0 | |

| Private | 0 | 1 (2.4) | |

| Economic status | |||

| Good | 7 (16.7) | 6 (14.3) | 0.812 |

| Moderate | 33 (78.6) | 33 (78.6) | |

| Bad | 2 (4.8) | 3 (7.1) | |

| Gravida | 2.04 ± 0.96 | 1.90 ± 0.98 | 0.503 |

| One | 15 (35.7) | 18 (42.9) | |

| Two | 13 (31) | 14 (33.3) | |

| Three | 11 (26.2) | 6 (14.3) | |

| Four | 3 (7.1) | 4 (9.5) | |

| Gestational age, wk | 18.26 ± 1.76 | 17.64 ± 1.69 | |

| 15-17 | 16 (38.1) | 23 (59) | 0.105 |

| 18-20 | 26 (61.9) | 19 (41) | 0.918 |

| Body mass index, kg/m 2 | 24.84 ± 4.70 | 24.74 ± 4.32 | |

| 15-18.49 | 3 (7.1) | 2 (4.8) | |

| 18.5-24.99 | 20 (47.6) | 20 (47.5) | |

| 25-29.99 | 11 (26.2) | 13 (31) | |

| 30-34.99 | 7 (16.7) | 7 (16.7) | |

| 35-39.99 | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Interval from previous pregnancy, y | 2.11 ± 1.83 | 1.8 ± 1.76 | 0.507 |

| No Interval | 15 (35.7) | 17 (40.5) | |

| 1 | 4 (9.5) | 3 (7.1) | |

| 2 | 2 (4.8) | 4 (9.5) | |

| 3 | 3 (7.1) | 5 (11.9) | |

| ≥ 4 | 18 (42.9) | 3 (31) | |

| Previous delivery | 0.797 | ||

| No Delivery | 17 (40.5) | 18 (42.9) | |

| C/S | 19 (45.2) | 20 (47.6) | |

| NVD | 6 (14.3) | 4 (9.5) | |

| Tendency of pregnancy, Mother | 0.415 | ||

| Yes | 35 (83.3) | 32 (76.2) | |

| No | 7 (16.7) | 10 (23.8) | |

| Tendency of pregnancy, Husband | 0.156 | ||

| Yes | 40 (95.2) | 35 (83.3) | |

| No | 2 (4.8) | 7 (16.7) | |

| Smoking Mother | |||

| Yes | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | 0.506 |

| No | 41 (97.6) | 41 (97.6) | |

| Smoking Husband | 0.73 | ||

| Yes | 21 (50) | 12 (28.6) | |

| No | 21 (50) | 30 (71.4) | |

| Satisfaction of Fetal Sex, Mother | |||

| Yes | 32 (78.6) | 26 (61.9) | 0.095 |

| No | 9 (21.4) | 16 (38.1) | |

| Satisfaction of Fetal Sex, Husband | 0.102 | ||

| Yes | 32 (76.2) | 25 (59.5) | |

| No | 10 (23.8) | 17 (40.5) | |

| History of Fetal Malformation in Previous Pregnancy | 0.433 | ||

| Yes | 5 (11.9) | 2 (4.8) | |

| No | 37 (88.2) | 40 (95.2) | |

| Marriage Status | 0.483 | ||

| Voluntary | 39 (92.9) | 38 (85.7) | |

| Mandatory | 3 (7.1) | 6 (14.3) | |

| Total | 42 (100) | 42 (100) |

a Data are presented as mean SD or No. (%).

b The P values were tested using the independent-samples t-test, Chi-square, and Fisher’s exact-test.

c Abbreviations: C/S: caesarian section; and NVD, normal vaginal delivery.

Table 2. Comparison of Seven Component of Sleep Quality and Previous Intervention in Pregnant Women a.

| Component of Sleep Quality | Case | Control | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective sleep quality (component 1) | |||

| Very Good | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.8) | 0.246 |

| Good | 21 (50) | 12 (28.6) | |

| Bad | 10 (23.8) | 16 (38) | |

| Very Bad | 10 (23.8) | 12 (28.6) | |

| Sleep latency (component 2) | 2.73 ± 1.62 | 2.61 ± 1.54 | 0.732 |

| 0 | 4 (9.5) | 3 (7.1) | |

| 1-2 | 15 (35.7) | 15 (35.7) | |

| 3-4 | 19 (45.2) | 21 (50) | |

| 5-6 | 4 (9.5) | 3 (7.1) | |

| Sleep duration (component 3), h | 6.22 ± 1.14 | 6.40 ± 1.12 | 0.474 |

| > 7 | 16 (38.1) | 21 (50) | |

| 6-7 | 10 (23.8) | 11 (26.2) | |

| 5-6 | 14 (33.3) | 7 (16.7) | |

| < 5 | 2 (4.8) | 3 (7.1) | |

| Habitual sleep efficiency (component 4), % | 72.58 ± 12.07 | 75.19 ± 10.30 | 0.288 |

| > 85 | 8 (19) | 6 (14.3) | |

| 75-84 | 11 (26.2) | 16 (38.1) | |

| 65-74 | 11 (26.2) | 17 (40.5) | |

| < 65 | 12 (28.6) | 3 (7.1) | |

| Sleep disturbances (component 5) | 10.07 ± 3.84 | 9.64 ± 3.25 | 0.583 |

| 1-9 | 23 (54.8) | 21 (50) | |

| 10-18 | 19 (45.2) | 21 (50) | |

| Use of sleeping medication (component 6) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Daytime dysfunction (component 7) | 3.38 ± 2.15 | 2.76 ± 1.49 | 0.130 |

| 0 | 5 (11.9) | 2 (4.8) | |

| 1-2 | 8 (19) | 15 (35.7) | |

| 3-4 | 13 (31) | 20 (47.6) | |

| 5-6 | 16 (38.1) | 5 (11.9) | |

| Sleep quality | 8.80 ± 2.73 | 8.47 ± 2.58 | 0.566 |

| 5-10 | 32 (76.2) | 33 (78.6) | |

| 11-21 | 10 (23.8) | 9 (21.4) | |

| Total | 42 (100) | 42 (100) | - |

a Data are presented as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b The P values were tested using independent-samples t-test or Chi-square test.

Table 3. Comparison of Depression in Evaluated Pregnant Women a.

| Depression | Previous Intervention | One Month After Intervention, Week 29 | Two Month After Intervention, Week 33 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (1-10) | |||

| Intervention | 0 (0) | 12 (28.6) | 15 (35.7) |

| Control | 0 (0) | 8 (19) | 7 (16.7) |

| Mild (11-20) | |||

| Intervention | 23 (54.8) | 15 (35.7) | 15 (35.7) |

| Control | 24 (57.1) | 22 (52.4) | 23 (54.7) |

| Moderate (21-30) | |||

| Intervention | 10 (23.8) | 8 (19) | 6 (14.3) |

| Control | 14 (33.3) | 9 (21.4) | 9 (21.4) |

| Severe (≥ 31) | |||

| Intervention | 9 (21.4) | 7 (16.6) | 6 (14.2) |

| Control | 4 (9.5) | 3 (7.2) | 3 (7.2) |

| Total | 42 (100) | 42 (100) | 42 (100) |

a Data are presented as No. (%).

Table 4. Depression Scores Before and at One (F1) and Two Month (F2) of Intervention in Pregnant Women a.

| Depression | Case | Control | P Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous intervention | 22.47 ± 10.08 | 20.69 ± 7.65 | 0.363 |

| One month after intervention (F1) (29 week) | 14.78 ± 10.14 | 19.57 ± 8.90 | 0.000 |

| Two month after intervention (F2) (33 week) | 13.33 ± 9.27 | 18.16 ± 10.20 | 0.000 |

a Data are presented as Mean ± SD.

b The P values were tested using the repeated measure A.

Figure 1. Depression Scores Before and at One (F1) and Two Month (F2) of Intervention in Pregnant Women.

5. Discussion

We could not find any literature concerning the effect of sleep health behavioral education on the depressed pregnant women with sleep disturbances. Nevertheless, given the frequently reported relationships between sleep disturbances and pregnancy also between sleep disturbances and depression (20), the findings of this study in the second trimester of pregnancy were not surprising. In addition to sleep quality and depression remained relatively stable during pregnancy. Sleep quality early pregnancy may contribute to the higher development levels of depressive symptoms in later pregnancy, Given that depressive symptoms can lead to clinical depression (35). When earlier pregnancy physical symptoms and later pregnancy sleep quality were entered in the regression analyses at the same time, earlier pregnancy sleep quality was not a significant predictor of later pregnancy depressive symptomatology as was shown by Skouteris et al. (35). Moreover, the stability of sleep disturbances across the second and third trimester is consistent with findings on sleep disturbances in pregnant women without depression (36). Whilst the majority of research has shown that sleep quality is a predictor of depressive symptoms (9, 20, 35, 37), women who experience greater frequency and severity effect of symptoms on life during earlier stages of pregnancy, also likely experience poorer sleep quality at later pregnancy. This poor sleep quality is associated with depressive symptoms, because of physical symptoms at early to middle second trimester would predict depressive symptoms in the last trimester, both directly and via poor sleep quality (prospectively) (9). It might be important to screen sleep difficulties during pregnancy and address these difficulties to prevent the development or further increases in depressive symptomatology at a life period when women’s wellbeing is particularly important. Indeed, there is evidence from the early postpartum period that women might report symptoms of depression as somatic complaints. This finding also suggests that when fatigue and insomnia are reported by women during the prenatal and postnatal periods, it may be important to check carefully for depressive symptoms as well (35). Disruptions in sleep appear as early as 11 to 12 weeks of gestation, intensify in the third trimester, and persist into the postpartum period. Studies have found that the experience of sleep problems during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of depression, both during the pregnancy and in the postpartum period. Clinically, the findings underscore the importance of assessing and monitoring sleep problems throughout the pregnancy and intervening accordingly to alleviate these symptoms and to improve the health-related quality of life of pregnant women. Higher depressed mood score was independently associated with lower health-related quality of life in six of the eight domains, including bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health (37). Field et al. stated that during both the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, the depressed women had more sleep disturbances and higher depression, anxiety, and anger scores. They also had higher norepinephrine and cortisol levels. The newborns of the depressed mothers also had more sleep disturbances including less time in deep sleep and more time in indeterminate (disorganized) sleep, and they were more active and cried more (20). The results of these studies were consistent with the recent research findings about relationship between depression on the second trimester pregnancy and sleep quality. The effect of health behavior educations on the depression in pregnant women with sleep disorder might be consistent with results of current research. The present study also confirmed the result of a pilot study on efficacy of sleep hygiene education on sleep quality in working women (38) that demonstrated significant association between sleep hygiene education and improved participants’ sleep quality. Influence of sleep health behavioral education on recovery of depression was consistent with current research. The studies in Iran showed the prevalence of depression in pregnant women as 25%, 28.8%, and 32% (39-41). This variation can be due to difference of Sleep quality regarding cultural conditions and appropriate culture conditions predisposing to depression. These results assist to homogenize demographic characteristics of pregnant women to remove the effects of confounding factors on the depression. It could help mothers with adaptation during and after pregnancy, promote maternal mental health by improving their communication skills, draw attention to her needs at this time, identify mothers at risk for depression and sleep disorders by routine prenatal care and counseling programs. Special programs for research and diagnosis of sleep disorders, troubleshooting the cause of the disturbance, and prevention of disorder should be designed to achieve the motto "Healthy mother and healthy child.” Moreover, future researchers may alter the sequence of education courses to confirm overall program effectiveness. We expect that the sleep quality factors that might affect pregnant women with economic difficulties were not addressed by the four-week sleep hygiene education program. Therefore, the association between personal economic issues and sleep quality deserves further examination in the future. Like other studies, this study had some limitations. During answering questions, there might be few mental disorders with little effect to answer questions, which was beyond the control of the researcher. Moreover, undiagnosed disease and the effect of changes in diet and exercise on sleep pattern could have affected the study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the pregnant women who participated in this research for their assistance and cooperation. We also express our thanks to all the staff in charge of study at Tehran and Urmia University of Medical Science for their cooperation.

References

- 1.Sieber S, Germann N, Barbir A, Ehlert U. Emotional well-being and predictors of birth-anxiety, self-efficacy, and psychosocial adaptation in healthy pregnant women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(10):1200–7. doi: 10.1080/00016340600839742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hueston WJ, Kasik-Miller S. Changes in functional health status during normal pregnancy. J Fam Pract. 1998;47(3):209–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKee MD, Cunningham M, Jankowski KR, Zayas L. Health-related functional status in pregnancy: relationship to depression and social support in a multi-ethnic population. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):988–93. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopes EA, Carvalho LB, Seguro PB, Mattar R, Silva AB, Prado LB, et al. Sleep disorders in pregnancy. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2004;62(2A):217–21. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2004000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moline M, Broch L, Zak R. Sleep Problems Across the Life Cycle in Women. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2004;6(4):319–30. doi: 10.1007/s11940-004-0031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National sleep foundation. Women and sleep. National sleep foundation; 2007. Available from: http://sleepfoundation.org/sleep-topics/women-and-sleep. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neau JP, Texier B, Ingrand P. Sleep and vigilance disorders in pregnancy. Eur Neurol. 2009;62(1):23–9. doi: 10.1159/000215877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KA, Gay CL. Sleep in late pregnancy predicts length of labor and type of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(6):2041–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamysheva E, Skouteris H, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ, Milgrom J. A prospective investigation of the relationships among sleep quality, physical symptoms, and depressive symptoms during pregnancy. J Affect Disord. 2010;123(1-3):317–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holcomb WJ, Stone LS, Lustman PJ, Gavard JA, Mostello DJ. Screening for depression in pregnancy: characteristics of the Beck Depression Inventory. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88(6):1021–5. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(96)00329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan H, Sadocks B. Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pazande F, Tomianc ZH, Afshar F, Valaei N. Prevalence of depression and its associated factors among pregnant women Teaching hospitals of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. Kermanshah Univ Med Sci J. 1998;21:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandad R, Abedian Z, Hasanabadi H, Esmaeili H. Sleep patterns associated with depression. Kermanshah Univ Med Sci J. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson TR. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):698–709. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gotlib IH, Whiffen VE, Mount JH, Milne K, Cordy NI. Prevalence rates and demographic characteristics associated with depression in pregnancy and the postpartum. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57(2):269–74. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akiskal HS. Mood disorders: Historical introduction and conceptual overview. In: Sadock B. J., Sadok V. A., editors. Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Da Costa D, Larouche J, Dritsa M, Brender W. Psychosocial correlates of prepartum and postpartum depressed mood. J Affect Disord. 2000;59(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steer RA, Scholl TO, Hediger ML, Fischer RL. Self-reported depression and negative pregnancy outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(10):1093–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90149-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitamura T, Sugawara M, Sugawara K, Toda MA, Shima S. Psychosocial study of depression in early pregnancy. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168(6):732–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.6.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M, Figueiredo B, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Sleep disturbances in depressed pregnant women and their newborns. Infant Behav Dev. 2007;30(1):127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gellis LA, Lichstein KL. Sleep hygiene practices of good and poor sleepers in the United States: an internet-based study. Behav Ther. 2009;40(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stepanski EJ, Wyatt JK. Use of sleep hygiene in the treatment of insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7(3):215–25. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzeng WC, Yang CI, Lin YR. [Sleep hygiene for female nurses]. J Nurs. 2005;52(3):71–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jefferson CD, Drake CL, Scofield HM, Myers E, McClure T, Roehrs T, et al. Sleep hygiene practices in a population-based sample of insomniacs. Sleep. 2005;28(5):611–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown FC, Buboltz WJ, Soper B. Relationship of sleep hygiene awareness, sleep hygiene practices, and sleep quality in university students. Behav Med. 2002;28(1):33–8. doi: 10.1080/08964280209596396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheek RE, Shaver JL, Lentz MJ. Variations in sleep hygiene practices of women with and without insomnia. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27(4):225–36. doi: 10.1002/nur.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atlantis E, Chow CM, Kirby A, Singh MA. Worksite intervention effects on sleep quality: a randomized controlled trial. J Occup Health Psychol. 2006;11(4):291–304. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buysse DJ, Reynolds C3, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao KW, Yu S, Cheng SP, Chen IJ. Relationships between personal, depression and social network factors and sleep quality in community-dwelling older adults. J Nurs Res. 2008;16(2):131–9. doi: 10.1097/01.jnr.0000387298.37419.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung KF, Tang MK. Subjective sleep disturbance and its correlates in middle-aged Hong Kong Chinese women. Maturitas. 2006;53(4):396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malekzadegan A. The effects of Relaxation exercise training on the sleep disorders in the third trimester of pregnancy, pregnant women referred to health centers in Zanjan. School of Nursing and Midwifery. Vol. 1385. Iran University of Medical Sciences in Iran: School of Nursing and Midwifery; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hossein Abadi R. The effect of acupressure on sleep quality in elderly. Tarbiatmodares University in Iran; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck AT, Beck RW. Screening depressed patients in family practice: a rapid technique. Postgrad Med. 1972;52:81–85. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1972.11713319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beck AT, Rial WY, Rickels K. Short form of depression inventory: cross-validation. Psychol Rep. 1974;34(3):1184–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skouteris H, Germano C, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ, Milgrom J. Sleep quality and depression during pregnancy: a prospective study. J Sleep Res. 2008;17(2):217–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mindell JA, Jacobson BJ. Sleep Disturbances During Pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2000;29(6):590–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2000.tb02072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Da Costa D, Dritsa M, Verreault N, Balaa C, Kudzman J, Khalife S. Sleep problems and depressed mood negatively impact health-related quality of life during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010;13(3):249–57. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen PH, Kuo HY, Chueh KH. Sleep hygiene education: efficacy on sleep quality in working women. J Nurs Res. 2010;18(4):283–9. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0b013e3181fbe3fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Modabernia J, Shojaei tehrani H, Heidarnezhad S. Prevalence of depression in the third trimester. Guilan Univ Med Sci. 2006;71:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Omidvar SH, KHeirkhah F, Azimi H. Depression in pregnancy and associated factors. Hormozgan Univ Med Sci. 2006;3:213–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shahmiri H, Momtazi S. Prevalence of depression and its relationship with the individual characteristics of pregnant women. Med JTabriz Univ Med Sci. 2005;2:83–6. [Google Scholar]