Abstract

Resistance to quinolone antibiotics has been associated with single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of gyrA. Mutations in the gyrA gene were compared by using mutant populations derived from wild-type Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis and its isogenic mutS::Tn10 mutator counterpart. Spontaneous mutants arising during nonselective growth were isolated by selection with either nalidixic acid, enrofloxacin, or ciprofloxacin. QRDR SNPs were identified in approximately 70% (512 of 695) of the isolates via colony hybridization with radiolabeled oligonucleotide probes. Notably, transition base substitution SNPs in the QRDR were dramatically increased in mutants derived from the mutS strain. Some, but not all, antibiotic-resistant mutants lacking QRDR SNPs were resistant to tetracycline and chloramphenicol, consistent with alterations in nonspecific efflux pumps or other membrane transport mechanisms. Changing the selection conditions shifted the mutation spectrum. Selection with ciprofloxacin was least likely to yield a mutant harboring either a QRDR SNP or chloramphenicol resistance. Selection with enrofloxacin was more likely to yield mutants containing Ser83→Phe mutations, whereas selection with ciprofloxacin or nalidixic acid favored recovery of Asp87→Gly mutants. Fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella strains isolated from veterinary or clinical settings frequently display a mutational spectrum with a preponderance of transition SNPs in the QRDR, the pattern found in vitro among mutS mutator mutants reported here. Both the preponderance of transition mutations and the varied mutation spectra reported for veterinary and clinical isolates suggest that bacterial mutators defective in methyl-directed mismatch repair may play a role in the emergence of quinolone and fluoroquinolone resistance in feral settings.

Quinolone and fluoroquinolone drugs are used against a broad spectrum of bacterial pathogens in human and veterinary medicine, and with increased use, resistance of Salmonella spp. to these antibiotics has been reported to be on the increase (34, 38). Resistance tends to appear at different times and in different places, raising the question of whether the spread of antibiotic resistance is truly clonal in origin.

Resistance to the quinolones and fluoroquinolones can arise by distinct pathways. Major targets for these antibiotics are the DNA topoisomerases required for bacterial replication. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) arise in gyrA, encoding the GyrA subunit of DNA gyrase, and allow relief from inhibition by the antibiotic without eliminating the essential function of the gene product. SNPs are clustered in a relatively short portion of gyrA called the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) (44). Many surveys of quinolone-resistant Salmonella strains from human and animal sources have associated nalidixic acid resistance with the frequent occurrence of QRDR SNPs (6, 13-15, 27, 35, 40, 43). While most of these reports focus on developed countries, it is clear that once resistance appears in developing countries, it can spread rapidly, as has nalidixic acid resistance in Thailand (16) and Vietnam (39).

High-level fluoroquinolone resistance does not develop by a single-step gyrA mutation, in contrast to nalidixic acid resistance (29, 34). parC, which encodes topoisomerase IV, is also targeted by quinolone antibiotics, presumably because the QRDR of parC is highly homologous to that of gyrA. Although mutations in parC are frequently encountered in gram-positive fluoroquinolone-resistant organisms (29), they are only rarely observed in Escherichia coli (42) and are generally absent in Salmonella mutants derived from either collections of field isolates (34) or from stepwise generation of high-level resistance in vitro (12). What appears to be the first example of a parC mutation in Salmonella was reported only recently (31).

Fluoroquinolone resistance can also be due to the mar (multiantibiotic resistance) locus (1, 29, 34, 36). This phenotype is associated with increased efflux across the cell membrane, altering sensitivity to several classes of antibiotics, including the fluoroquinolones, and to tetracycline and chloramphenicol. The phenotype is more often associated with alterations in structure or expression of regulatory proteins (marRAB, marC, or soxRS products) than with the structural proteins of the pump itself (AcrAB and TolC). Removal of OmpF, a porin, produces a similar phenotype in other species but has rarely been reported in Salmonella spp.

The role that particular mutators, namely those which are defective in methyl-directed mismatch repair (MMR), might play in the emergence of antibiotic resistance in enteric bacteria has recently attracted much attention (7, 18, 21, 33, 37). It was demonstrated previously that MMR mutators are disproportionately represented in natural populations of bacteria (21). It was also shown that selection pressures, when placed on bacterial populations, culled and selectively increased the numbers of MMR mutators. For example, the selection of histidine prototrophs from a population of Salmonella histidine auxotrophs (22) or of Lac+ events from an E. coli Lac− population (28) increased the numbers of MMR mutators 100- to 1,000-fold. By imposing further rounds of selection pressures, using antibiotic selection, for example, Miller et al. (28) showed that the MMR mutators could be selectively increased to 100% of the population. The significance of MMR mutators in the clinical setting was recently reinforced when it was shown that a high proportion of antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates derived from cystic fibrosis patients were MMR mutators (33). As P. aeruginosa is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in individuals with cystic fibrosis, patients are treated with a long-term regimen of antibiotics. It was reasoned that such usage of antibiotics most likely selected for the mutator phenotype (20, 33).

Inactivation of MMR leads to a dramatic increase in both transition base pair substitutions and frameshift mutations (8), thus yielding mutational spectra distinct from those obtained from the corresponding nonmutators. These patterns were borne out in previous studies of E. coli and Salmonella mutators isolated from natural populations (22, 23). Alterations in mutation spectra due to DNA repair defects have been used in a variety of systems to document the physiology of the cells in which mutations have occurred. For example, mutational patterns associated with the hereditary excision repair defect found in patients with xeroderma pigmentosum are reflected in the p53 mutations identified in the skin carcinomas to which these patients are prone (26). Here, we compare the spectra of mutations obtained from mutant populations of MMR-proficient or -deficient Salmonella strains derived under selection using nalidixic acid, enrofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin.

(Portions of this work were presented previously [D. D. Levy, B. Sharma, and T. A. Cebula, Abstr. 102nd Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. A-5, 2002].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

Strain SL223 (a nonmutator) was single-colony isolated from strain C384, a Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis strain from a salmonellosis outbreak. Strain SL223 was transduced by phage P22 grown on strain TT20021 (S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 [hisD3052 mutS121::Tn10]) kindly supplied by M. Carter from the collection of J. Roth (University of Utah). Strain SL226 (a mutator) was isolated as a tetracycline-resistant transductant with an elevated mutation frequency on rifampin and nalidixic acid.

gyrA mutation spectra.

Both mutator (SL226) and nonmutator (SL223) strains were inoculated from frozen glycerol stocks into brain heart infusion (BHI) broth, and 24 to 72 3-ml portions were shaken overnight (18 to 22 h) at 37°C. Mutants were identified by plating 100 to 300 μl onto Luria-Bertani (LB) agar containing 50 μg of nalidixic acid (Sigma Chemical Co.) per ml, 0.25 μg of enrofloxacin (Baytril, 99.9%; Bayer Corp., Kansas City, Mo.) per ml, or 0.05 μg of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (Bayer, Kankakee, Ill.) per ml. Antibiotics were used at or just above MICs as determined by growth on agar plates. Identical mutations found in separate tubes were independent events, reducing the likelihood that characterization of sibling progeny of an organism with the initial mutagenic event would distort the mutation spectrum. Serial dilutions of the contents of some of the tubes (5 to 12 tubes) were plated in triplicate on nonselective LB agar plates, and colonies were counted to evaluate mutation frequencies. Colonies found on selective plates were isolated as single colonies once on the same medium and a second time on a nonselective medium to avoid the selection of secondary mutations arising during subsequent handling.

The use of oligonucleotides to probe bacterial colonies is a technique long cited in the bacterial mutagenesis literature as a means of identifying SNPs (5, 9). Oligonucleotide probes, described in Fig. 1, were used to detect mutations in gyrA. Colony hybridization was performed as described previously (19). Briefly, colonies were grown on BHI agar plates overnight and transferred to paper filters. The bacterial mass was lysed and dried onto the filter and then probed with γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotide probes at 57 to 60°C, depending on the oligonucleotide. The use of short (18- to 19-mer) probes and stringent hybridization and washing conditions allowed for discrimination of single-base-pair differences. Mutants which showed hybridization to only wild-type probes (or with anomalous probe results) were checked by DNA sequencing.

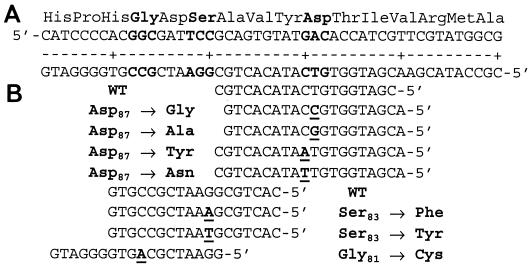

FIG. 1.

(A) Amino acid and nucleotide sequences of the QRDR of S. enterica; (B) sequences of probes used to identify the QRDR sequence. The underlined altered base causes the mutation listed to the left or right of the probe sequence.

Primers 5′-GTGTTATAATTTGCGACCTTT and 5′-CCAGGCAGCCGTTAATCACT were based on S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain LT2 (30) taken from prepublication descriptions available on the University of Washington website. These primers were used to amplify a 639-bp product of the 5′ end of gyrA. To prepare template DNA, 100 μl of an overnight culture in LB agar was washed with 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline and resuspended in 100 μl of distilled and deionized water (QB Biological, Gaithersburg, Md.), placed in a boiling water bath for 5 to 10 min, and then centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000 × g. The 50-μl reaction mixture contained 2 μl of the supernatant fluid, 20 pmol of each primer, a 200 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.), 5 mM MgCl2, AmpliTaq buffer, and 0.25 U of AmpliTaq polymerase (Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, N.J.). After an initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, amplification proceeded for 35 cycles of 92°C (30 s), 60°C (1 min), and 72°C (1 min), with a final 15-min extension at 72°C in an MJ Research PTC200 thermocycler. Following cleanup with either QIAquick PCR purification columns (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.) or ExoSap nuclease (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, N.J.), the PCR product was sequenced (Amplicon Express, Pullman, Wash.) by using dye-labeled terminators and primer 5′-GCCGGTACACCGTCGCGTACTTT, which anneals to a sequence located about halfway between the start codon and the QRDR.

To sequence the Salmonella parC gene, primers 5′-AATGAGCGATATGGCAGAGC and 5′-AACATTTTCGGTTCCTGCATG were used. They were derived from genomic sequencing of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (30) and amplify a 450-bp product. Sequencing was performed as described for gyrA, except that the first amplification primer listed above was also used as a sequencing primer, and denaturation took place at 55°C during thermal cycling.

Antimicrobial resistance was measured with a disk diffusion assay (32). Strains were inoculated into BHI broth directly from frozen stocks. During the early stationary phase (1 < optical density at 600 nm < 2), an aliquot was diluted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.1 and plated on Mueller-Hinton agar, and Sensi-Discs (Becton Dickinson, Paramus, N.J.) containing antibiotic were applied. Zone diameters were measured after growth overnight at 37°C. When no growth inhibition was apparent, a zone diameter of 6 mm, the diameter of the disk, was used to calculate the average values for replicate experiments.

Statistics.

Fisher's exact test was used to compare ratios (e.g., frequencies of transversions, mutations in the QRDR versus elsewhere, and mutations at various sites within the QRDR). Antibiotic sensitivity (measured by a disk diffusion assay) was evaluated by Student's t test to compare the averages of multiple strains, and the variances were compared by the F distribution test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

S. enterica serovar Enteritidis wild-type strain SL223 and mutS strain SL226, which are sensitive to all quinolone antibiotics, were grown overnight in rich media without selection. Antibiotic-resistant mutants arising spontaneously during this growth period were isolated by selection on plates containing nalidixic acid, enrofloxacin, or ciprofloxacin. As expected, isolates resistant to these antibiotics were found 2 to 3 orders of magnitude more frequently in the mutator strain than in the repair-proficient strain, presumably due to the higher level of spontaneous base substitution mutation during replication (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Isolation of antibiotic-resistant mutants

| Strain and antibiotica in growth medium | Mutation frequency (106) | No. of isolates | No. (%) of mutations on gyrA | No. (%) of transversions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL223 | ||||

| NAL | 0.0033 | 60 | 52 (87) | 15 (29) |

| ENR | 0.014 | 189 | 149 (79) | 55 (37) |

| CIP | 0.010 | 123 | 79b (64) | 28 (35) |

| SL226 | ||||

| NAL | 3.4 | 69 | 67 (97) | 0c (0) |

| ENR | 0.24 | 111 | 108 (97) | 1c (1) |

| CIP | 2.4 | 143 | 57d (40) | 6c,e (11) |

NAL, nalidixic acid; ENR, enrofloxacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin.

Significantly lower than value for strain SL223 grown in nalidixic acid or enrofloxacin (P < 0.02).

Significantly lower than values for strain SL223 (P < 0.001).

Significantly lower than value for strain SL226 grown in nalidixic acid or enrofloxacin or strain SL223 grown in ciprofloxacin (P < 10−6).

Significantly higher than value for strain SL226 grown in nalidixic acid or enrofloxacin (P < 0.02).

Mutant colonies were screened for common mutations in the QRDR by annealing a set of probes capable of discriminating SNPs, a standard technique for studies of bacterial mutagenesis (5, 9). The panel of probes was able to identify a mutation in 40 to 97% of the isolates (Table 1). This technology is faster, more reliable, and less expensive than more recently developed techniques such as real-time PCR (27, 40), restriction fragment length polymorphism (12), and denaturing by high-pressure liquid chromatography (10).

Most mutants contained a single mutation in the QRDR that was identified by the probe hybridization technique. The distribution of these mutations is presented in Fig. 2. In almost all cases, probe analysis identified the wild-type sequence or an expected SNP. To confirm the specificity of the probes, DNA was PCR amplified from randomly selected colonies (30 of 512 [6%] of colonies with SNPs and 24 of 183 [13%] of isolates to which wild-type sequence probes hybridized). DNA sequencing of each PCR product confirmed the genotype identified by probe hybridization.

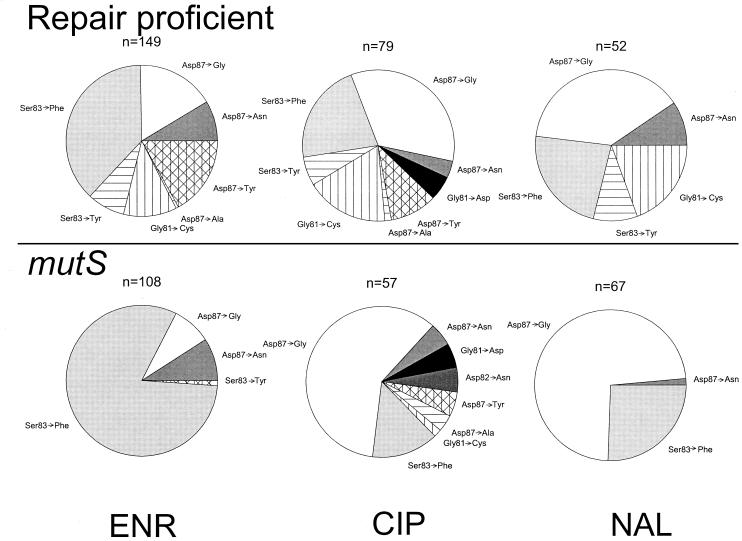

FIG. 2.

Spectrum of QRDR SNPs recovered after selection by the indicated antibiotic. White and solid-color pie slices represent transition base substitution mutations; hatched and striped areas indicate transversions. ENR, enrofloxacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; NAL, nalidixic acid; n, total number of strains with QRDR SNPs.

The probe hybridization data were inconclusive for 11 of 695 isolates, all from colonies derived by ciprofloxacin selection. In each of these 11 inconclusive cases, DNA sequencing revealed the presence of a QRDR SNP not specifically targeted by the panel of probes: Asp82→Asn (found in three independent mutants in the SL226 spectrum), Gly81→Asp (found four times with SL223 and three times with SL226), or Ser83→Ala (found once with SL223).

Most of the mutations identified in the mismatch repair-deficient strain were transition mutations (Table 1), as expected for this phenotype (8). The mutation spectra derived for the mutator strain were considerably less complex due to the absence of transversion SNPs. Virtually all mutator mutants contained either Ser83→Phe or Asp87→Gly QRDR mutations. The relative frequency of each of these mutations, however, depended on the antibiotic used for selection. For example, the Ser83→Phe mutation was significantly more frequent in mutants derived with enrofloxacin and significantly less frequent when nalidixic acid or ciprofloxacin was used in selection of mutants (P < 10−8, Fisher's exact test). Similar trends are evident in mutants selected from the nonmutator strain (Fig. 2, top). The increased frequency of Ser83→Phe mutations compared to Asp87→Gly mutations is significant with enrofloxacin selection (P = 10−5). For selection with ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid, the relative frequencies of these two mutations are reversed, but the difference is of borderline significance when the frequencies are compared directly (P of 0.055 and 0.068, respectively). Comparing the same frequencies between spectra, the increased frequency of Ser83→Phe mutations in nonmutators under enrofloxacin versus ciprofloxacin or nalidixic acid selection is highly significant (P < 10−7). The decreased frequency at which Asp87→Asn mutations were found was also significant (P of 0.0090 and 0.043 for ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid, respectively). Changes in frequencies for other mutations were not significant, except for the increase in transversion mutations discussed earlier.

The patterns of mutation leading to quinolone resistance in Salmonella described here are remarkably different from those found in E. coli (11, 42). The spectrum of QRDR SNPs is simpler, with fewer of the possible SNPs reported, although the occurrence of two SNPs in the same isolate is quite common. This may be due, at least in part, to the influence of the surrounding nucleic acid sequence on the frequency of gene mutation. The QRDR appears to be a hot spot for genetic variation in a region of gyrA that is otherwise highly conserved across a broad range of species (41). A single-base-pair change can have far-reaching consequences on the mutation rate at both nearby and distal portions of the surrounding sequence (24, 25). Thus, gene polymorphisms confined to silent changes in the third positions of codons may have contributed to the differences in mutation spectra observed between E. coli and Salmonella.

We next compared the mutation spectra generated in vitro with reports of gyrA SNPs in the literature. While most of these are case reports or describe small collections of strains, several larger surveys of Salmonella (>30 QRDR mutants) have been reported. Three features are immediately obvious from comparisons of the data from these surveys with one another and with the data reported here (Fig. 3). First, selection of quinolone-resistant strains from veterinary or clinical populations almost invariably resulted in Salmonella strains with QRDR SNPs. Second, transversion mutations were rare in most, but not all, of these studies. Finally, the relative frequency of each mutation within the QRDR differed widely from study to study. Each of these features is remarkably similar to the patterns of mutation in the QRDR region of MMR mutators reported here, consistent with the hypothesis that the QRDR SNPs in these veterinary and clinical isolates arose in organisms defective in MMR.

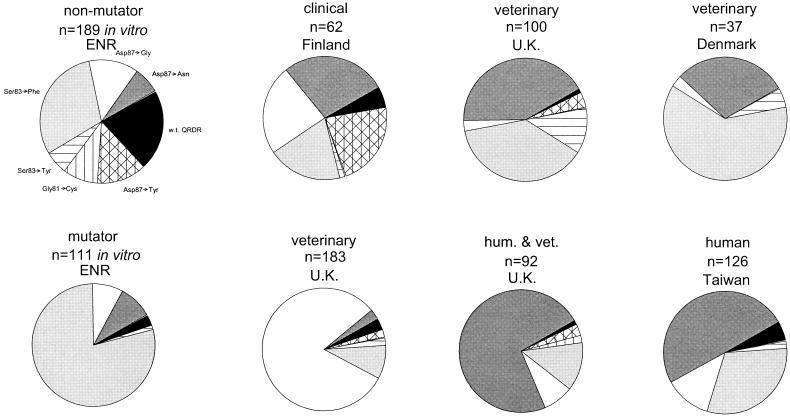

FIG. 3.

Comparison of in vitro results (see Fig. 2 and Table 1) with literature reports of QRDR SNPs in collections of Salmonella strains isolated from veterinary and human infections. Clockwise from top left, the data are from the present paper (SL223 selected with enrofloxacin); from works cited in references 15, 27, 43, 6, 40, and 35; and from the present paper (SL226 selected with enrofloxacin). Solid black indicates a wild-type (w.t.) QRDR sequence. Transition mutations are indicated by shaded portions, and transversions are indicated by hatched or striped portions.

The relative rarity of transversion mutations in most of the field isolates described in Fig. 3 suggests that many strains had defective MMR at the time the mutation occurred. It is also consistent with the hypothesis that MMR-defective strains are common enough to be an important factor in the emergence of new traits within a population (21) but unstable enough to require restoration of replication fidelity via recombination (2, 3). It was recently shown that mutS recombination is even more frequent among salmonellae in the genetically homogeneous strains of the Salmonella reference collection B than in the genetically diverse Salmonella reference collection C strains (4). This finding suggests that the recombination frequency rises within the species among organisms that are genetically similar and that also share similar niches, further increasing opportunities for genetic exchange.

parC mutations are occasionally found in fluoroquinolone-resistant E. coli but are rare in Salmonella. To determine the role of parC inactivation in our collection, 24 mutants which lacked QRDR SNPs and were sensitive to chloramphenicol were selected. This sample contained equal numbers of mutator and nonmutator mutants, and representative sports were picked under selection conditions with each of the three antibiotics. The sequence of the 5′ end of the gene (corresponding to codons 9 to 145) in all 24 mutants and in the two parental strains was identical to the GenBank entry for parC obtained during whole-genome sequencing of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (30). Thus, spontaneous mutations in parC were not a frequent cause of quinolone resistance in Salmonella in this in vitro selection system.

We next tested the mutants' degree of resistance to each of the three antibiotics by a disk diffusion assay. All mutants with a specific mutation were screened unless there were sufficient numbers to justify random selection (Table 2). Most isolates with the same QRDR SNP had similar zones of inhibition, with the standard deviation being generally less than 10% of the mean.

TABLE 2.

Zone diameters around disks containing nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, or enrofloxacin in a Kirby-Bauer assay

| Mutation | No. of samples tested | Zone diam (mm [mean ± SD]) for disks containing:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nalidixic acid | Ciprofloxacin | Enrofloxacin | ||

| Control | 13 | 23.2 ± 1.8 | 30.7 ± 1.3 | 29.6 ± 1.5 |

| Wild-type gyrA | 116 | 14.7 ± 6.0 | 28.4 ± 3.5 | 25.8 ± 3.1 |

| Asp87→Asn | 6 | 6.0a ± 0.0 | 25.2 ± 2.3 | 24.0 ± 1.7 |

| Asp87→Gly | 33 | 6.6a ± 0.7 | 27.2 ± 2.3 | 24.6 ± 2.3 |

| Asp87→Tyr | 3 | 6.0a ± 0.0 | 24.7 ± 1.0 | 22.0 ± 1.0 |

| Ser83→Phe | 17 | 6.0a ± 0.0 | 24.6 ± 1.2 | 22.2 ± 1.5 |

| Ser83→Tyr | 5 | 6.0a ± 0.0 | 25.3 ± 0.7 | 22.6 ± 1.1 |

| Gly81→Cys | 10 | 9.8 ± 3.4 | 26.2 ± 1.4 | 24.3 ± 2.1 |

| Asp87→Ala | 4 | 8.0a ± 3.4 | 25.8 ± 2.2 | 23.0 ± 1.4 |

| Asp82→Asn | 2 | 7.0a | 24.4 | 23.0 |

| Asp82→Ile | 1 | 16.0 | 26.0 | 24.0 |

| Gly81→Asp | 3 | 17.3 ± 6.0 | 28.3 ± 2.5 | 25.7 ± 2.1 |

| Ser83→Ala | 1 | 16.0 | 29.0 | 28.0 |

| NCCLS breakpoint | 13.0 | 21.0 | NAb | |

No zone of inhibition was observed, so the 6-mm diameter of the disk was arbitrarily used to calculate this value.

NA, not available.

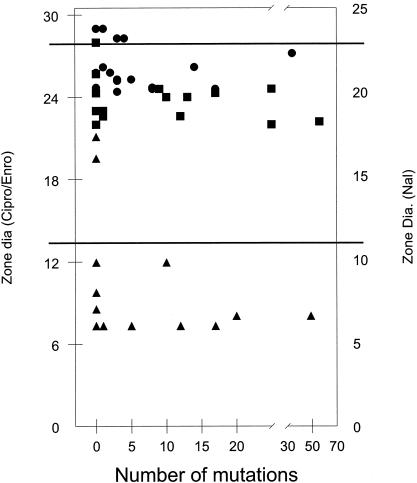

A plot of the frequency with which mutants were recovered in the mutation spectrum versus the diameter of the zone of inhibition (Fig. 4) failed to reveal a correlation between these two parameters. Thus, the frequency of recovery of any particular mutation was not influenced by the antibiotic sensitivity of strains carrying that mutation. Selection following in vitro growth in nonselective medium maximized the probability that mutants in this collection had a single change. The diameter of the zone of inhibition was not affected by the antibiotic used for selection for any of the sequence changes (data not shown). Resistance to quinolone antibiotics was more variable in the previously cited reports of strains isolated from clinical and veterinary settings. Eightfold differences in MIC and 10-mm differences in disk zone diameter were commonly reported. Thus, it appears that fluoroquinolone-resistant strains collected from clinical or veterinary sources contain a variety of uncharacterized alterations in addition to the QRDR SNP which affected fluoroquinolone sensitivity.

FIG. 4.

Antibiotic sensitivity (measured by the zone of inhibition in the disk diffusion assay) as a function of the number of times the mutation was recovered following selection with nalidixic acid (Nal) (▴), ciprofloxacin (Cipro) (•), or enrofloxacin (Enro) (▪). Zone diameters for unmutated parental strains are indicated by the upper horizontal line. The lower horizontal line indicates the NCCLS breakpoint for intermediate ciprofloxacin sensitivity and for nalidixic acid resistance.

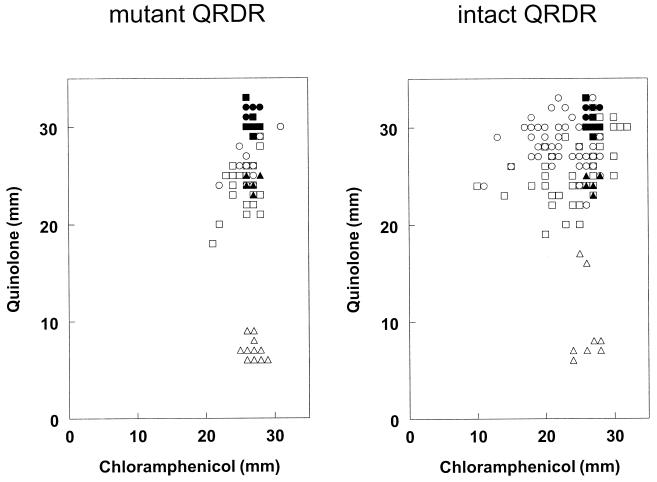

Many mutants, particularly those found after selection with ciprofloxacin, had no mutation in the QRDR. Reports in the literature suggest that many fluoroquinolone-resistant salmonellae have mutations in membrane transporter systems that render the strain resistant to a variety of antibiotics. To assess the frequency of these multiantibiotic-resistant mutants in our collection, we tested 115 of them for resistance to chloramphenicol. Nonmutators were tested for resistance to tetracycline as well. (All SL226 isolates are Tetr due to the Tn10 insertion in mutS.) Replicate samples of the original SL223 and SL226 strains were sensitive to these antibiotics, with zone diameters within the range prescribed for the NCCLS E. coli control strain. In addition, 75 mutants with QRDR SNPs were tested, all of which were sensitive to chloramphenicol.

The diameter of the zone of inhibition was slightly smaller for strains with a missense QRDR SNP than for those without a QRDR mutation (23.4 versus 26.2 mm). Closer inspection of the data revealed that the small difference in mean MICs between mutants with and without a QRDR SNP, while highly significant (P = 10−8, Student's t test), disguised considerable diversity among the individual mutants (F distribution, P < 0.003). As illustrated in Fig. 5, the range of zone diameters for isolates with no QRDR SNP extended both higher and lower than the range for mutants with a QRDR SNP. Replicate assays of the parental strains resulted in a diameter of 26 to 28 mm around a chloramphenicol disk. The zone diameters for mutants with a QRDR SNP were mostly in the same range, although for 16% (10 of 63), the diameters were slightly smaller (range, 21 to 25 mm). In contrast, 59% (68 of 115) of the quinolone-resistant isolates lacking QRDR SNPs were less sensitive to chloramphenicol than were the quinolone-sensitive isolates. Many of these (29 of 115 [25%]) had a zone of inhibition around the chloramphenicol disk that was smaller (<21 mm) than that of any isolate with a mutated QRDR. A small number (6 of 115 [5%]) were hypersensitive to chloramphenicol, with inhibition zones of up to 32 mm.

FIG. 5.

Antibiotic sensitivity (measured by the zone of inhibition) of strains with QRDR SNPs (left panel) or with no QRDR SNP (right panel) under selection conditions with nalidixic acid (▵), ciprofloxacin (○), or enrofloxacin (□). Filled symbols indicate data for antibiotic-sensitive control strains.

Selection with fluoroquinolone yielded mutants with the greatest variety of phenotypes. In addition to those with mutations in the QRDR, many had reduced sensitivity to chloramphenicol or tetracycline or were hypersensitive to those antibiotics, presumably because of alterations in efflux pumps or other transporters. Nalidixic acid selection generally yielded mutants that contained QRDR SNPs (119 of 129 isolates). Conspicuously, the few mutants from this population not harboring a QRDR SNP did not display increased resistance to chloramphenicol or tetracycline. That is, testing all 10 of these strains resulted in a population that, while small, was nonetheless large enough to have significantly fewer strains with reduced sensitivity to chloramphenicol than those selected by using either of the two fluoroquinolones (P = 0.0001, Fisher's exact test). This suggests that multidrug-resistant phenotypes associated with efflux pumps and other membrane transport mechanisms occur as secondary mutations during selection with nalidixic acid or are associated with selection with fluoroquinolone.

Most studies of clinical or veterinary isolates relied exclusively on nalidixic acid screening. This technique resulted in identification of a collection of mutants with QRDR SNPs similar to those of the mutation spectrum obtained with a mutant population derived under in vitro selection, also using nalidixic acid (Table 1). Two studies that employed ciprofloxacin to select isolates had high frequencies of resistant strains lacking QRDR SNPs (6, 15), similar to those of isolates selected with fluoroquinolone antibiotics following in vitro growth (Table 1). Thus, QRDR SNPs may be more closely associated with nalidixic acid resistance than with fluoroquinolone resistance and may not be necessary as the first step towards high-level fluoroquinolone resistance outside the laboratory.

In prior reports, comparisons of QRDR SNPs with other phenotypes such as phage type (40), with sensitivity to quinolone antibiotics (13), or with sensitivity to other classes of antibiotics (27) failed to produce convincing correlations. Furthermore, there is remarkably little consistency in the pattern of SNPs isolated from various populations (Fig. 3). Overall, these data strongly suggest that, if the spread of fluoroquinolone resistance is clonal, the important genetic loci remain to be identified and that QRDR SNPs arise often, independently, and not as the initial step.

It has been suggested that MMR mutator strains be used routinely to discover new mechanisms of antibiotic resistance that are likely to emerge in natural populations (A. J. O'Neill and I. Chopra, Letter, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1599-1600, 2001). Differences between patterns of mutation in MMR mutators and DNA repair-proficient organisms may explain some of the discrepancies found between natural isolates and those generated in vitro by stepwise selection protocols (for examples, see references 12 and 17). While mutations generated in vitro cannot always be tolerated by strains which must survive in more challenging environments (12), by starting with an MMR-deficient strain in vitro, we have generated a collection of mutants, each likely containing a single-step mutation, which may be useful in identifying new loci important for fluoroquinolone resistance. Fluoroquinolone-resistant strains isolated from clinical and veterinary settings could then be examined for these changes.

In summary, the spectra of mutations recovered in collections of quinolone-sensitive Salmonella strains were sensitive to both metabolic characteristics of the strain (e.g., the mutator phenotype) and the conditions of selection (e.g., the antibiotics used). Nonmutators selected with fluoroquinolone antibiotics frequently contained mutations outside of the gyrA QRDR, unlike Salmonella spp. isolated from clinical or veterinary sources. The lack of consistency among mutation spectra reported for clinical and veterinary samples suggests a wide variability in the conditions under which the mutations in those strains arose. However, the patterns of mutation are consistent with an overrepresentation of strains exhibiting mutation patterns of the MMR mutator phenotype among Salmonella spp. developing resistance to fluoroquinolone antibiotics worldwide. The promiscuity of MMR strains might also lead to a variety of recombinational events among strains in clinical and veterinary settings, explaining the heterogeneity of phenotypes reported in quinolone- and fluoroquinolone-resistant strains isolated from those settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank W. L. Payne for assistance with strain construction, J. Roth for bacterial strains, and J. LeClerc and E. Liebana for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alekshun, M. N., and S. B. Levy. 1999. The mar regulon: multiple resistance to antibiotics and other toxic chemicals. Trends Microbiol. 7:410-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown, E. W., M. L. Kotewicz, and T. A. Cebula. 2002. Detection of recombination among Salmonella enterica strains using the incongruence length difference test. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 24:102-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, E. W., J. E. LeClerc, B. Li, W. L. Payne, and T. A. Cebula. 2001. Phylogenetic evidence for horizontal transfer of mutS alleles among naturally occurring Escherichia coli strains. J. Bacteriol. 183:1631-1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, E. W., M. K. Mammel, J. E. LeClerc, and T. A. Cebula. 2003. Limited boundaries for extensive horizontal gene transfer among Salmonella pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:15676-15681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cebula, T. A., and W. H. Koch. 1990. Analysis of spontaneous and psoralen-induced Salmonella typhimurium hisG46 revertants by oligodeoxyribonucleotide colony hybridization: use of psoralens to cross-link probes to target sequences. Mutat. Res. 229:79-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiu, C. H., T. L. Wu, L. H. Su, C. Chu, J. H. Chia, A. J. Kuo, M. S. Chien, and T. Y. Lin. 2002. The emergence in Taiwan of fluoroquinolone resistance in Salmonella enterica serotype choleraesuis. N. Engl. J. Med. 346:413-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chopra, I., A. J. O'Neill, and K. Miller. 2003. The role of mutators in the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Drug Resist. Updates 6:137-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox, E. C. 1995. Recombination, mutation and the origin of species. Bioessays 17:747-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeMarini, D. M., M. L. Shelton, and J. G. Levine. 1995. Mutation spectrum of cigarette smoke condensate in Salmonella: comparison to mutations in smoking-associated tumors. Carcinogenesis 16:2535-2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eaves, D. J., E. Liebana, M. J. Woodward, and L. J. V. Piddock. 2002. Detection of gyrA mutations in quinolone-resistant Salmonella enterica by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4121-4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everett, M. J., Y. F. Jin, V. Ricci, and L. J. V. Piddock. 1996. Contributions of individual mechanisms to fluoroquinolone resistance in 36 Escherichia coli strains isolated from humans and animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2380-2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giraud, E., A. Brisabois, J.-L. Martel, and E. Chaslus-Dancla. 1999. Comparative studies of mutations in animal isolates and experimental in vitro- and in vivo-selected mutants of Salmonella spp. suggest a counterselection of highly fluoroquinolone-resistant strains in the field. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2131-2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griggs, D. J., K. Gensberg, and L. J. V. Piddock. 1996. Mutations in gyrA gene of quinolone-resistant salmonella serotypes isolated from humans and animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1009-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griggs, D. J., M. C. Hall, Y. F. Jin, and L. J. Piddock. 1994. Quinolone resistance in veterinary isolates of Salmonella. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33:1173-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakanen, A., P. Kotilainen, J. Jalava, A. Siitonen, and P. Huovinen. 1999. Detection of decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility in salmonellas and validation of nalidixic acid screening test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3572-3577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isenbarger, D. W., C. W. Hoge, A. Srijan, C. Pitarangsi, N. Vithayasai, L. Bodhidatta, K. W. Hickey, and P. D. Cam. 2002. Comparative antibiotic resistance of diarrheal pathogens from Vietnam and Thailand, 1996-1999. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:175-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kern, W. V., M. Oethinger, A. S. Jellen-Ritter, and S. B. Levy. 2000. Non-target gene mutations in the development of fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:814-820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komp Lindgren, P., A. Karlsson, and D. Hughes. 2003. Mutation rate and evolution of fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from patients with urinary tract infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3222-3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kupchella, E., W. H. Koch, and T. A. Cebula. 1994. Mutant alleles of tRNA(Thr) genes suppress the hisG46 missense mutation in Salmonella typhimurium. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 23:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LeClerc, J. E., and T. A. Cebula. 2000. Pseudomonas survival strategies in cystic fibrosis. Science 289:391-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeClerc, J. E., B. Li, W. L. Payne, and T. A. Cebula. 1996. High mutation frequencies among Escherichia coli and Salmonella pathogens. Science 274:1208-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LeClerc, J. E., W. L. Payne, E. Kupchella, and T. A. Cebula. 1998. Detection of mutator subpopulations in Salmonella typhimurium LT2 by reversion of his alleles. Mutat. Res. 400:89-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy, D. D., and T. A. Cebula. 2001. Fidelity of replication of repetitive DNA in mutS and repair proficient Escherichia coli. Mutat. Res. 474:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy, D. D., A. D. Magee, C. Namiki, and M. M. Seidman. 1996. The influence of single base changes on UV mutational activity at two translocated hotspots. J. Mol. Biol. 255:435-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy, D. D., A. D. Magee, and M. M. Seidman. 1996. Single nucleotide positions have proximal and distal influence on UV mutation hotspots and coldspots. J. Mol. Biol. 258:251-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy, D. D., M. Saijo, K. Tanaka, and K. H. Kraemer. 1995. Expression of a transfected DNA repair gene (XPA) in xeroderma pigmentosum group A cells restores normal DNA repair and mutagenesis of UV-treated plasmids. Carcinogenesis 16:1557-1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liebana, E., C. Clouting, C. A. Cassar, L. P. Randall, R. A. Walker, E. J. Threlfall, F. A. Clifton-Hadley, A. M. Ridley, and R. H. Davies. 2002. Comparison of gyrA mutations, cyclohexane resistance, and the presence of class I integrons in Salmonella enterica from farm animals in England and Wales. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1481-1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao, E. F., L. Lane, J. Lee, and J. H. Miller. 1997. Proliferation of mutators in a cell population. J. Bacteriol. 179:417-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez, J. L., A. Alonso, J. M. Gomez-Gomez, and F. Baquero. 1998. Quinolone resistance by mutations in chromosomal gyrase genes. Just the tip of the iceberg? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 42:683-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McClelland, M., K. E. Sanderson, J. Spieth, S. W. Clifton, P. Latreille, L. Courtney, S. Porwollik, J. Ali, M. Dante, F. Du, S. Hou, D. Layman, S. Leonard, C. Nguyen, K. Scott, A. Holmes, N. Grewal, E. Mulvaney, E. Ryan, H. Sun, L. Florea, W. Miller, T. Stoneking, M. Nhan, R. Waterston, and R. K. Wilson. 2001. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature 413:852-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakaya, H., A. Yasuhara, K. Yoshimura, Y. Oshihoi, H. Izumiya, and H. Watanabe. 2003. Life-threatening infantile diarrhea from fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella enterica Typhimurium with mutations in both gyrA and parC. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:255-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 6th ed. Approved standard M2-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 33.Oliver, A., R. Canton, P. Campo, F. Baquero, and J. Blazquez. 2000. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science 288:1251-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piddock, L. J. 2002. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Salmonella serovars isolated from humans and food animals. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piddock, L. J., V. Ricci, I. McLaren, and D. J. Griggs. 1998. Role of mutation in the gyrA and parC genes of nalidixic-acid-resistant Salmonella serotypes isolated from animals in the United Kingdom. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 41:635-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poole, K. 2001. Multidrug resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:500-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka, M. M., C. T. Bergstrom, and B. R. Levin. 2003. The evolution of mutator genes in bacterial populations: the roles of environmental change and timing. Genetics. 164:843-854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Threlfall, E. J. 2002. Antimicrobial drug resistance in Salmonella: problems and perspectives in food- and water-borne infections. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26:141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wain, J., N. T. Hoa, N. T. Chinh, H. Vinh, M. J. Everett, T. S. Diep, N. P. Day, T. Solomon, N. J. White, L. J. Piddock, and C. M. Parry. 1997. Quinolone-resistant Salmonella typhi in Viet Nam: molecular basis of resistance and clinical response to treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 25:1404-1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker, R. A., N. Saunders, A. J. Lawson, E. A. Lindsay, M. Dassama, L. R. Ward, M. J. Woodward, R. H. Davies, E. Liebana, and E. J. Threlfall. 2001. Use of a LightCycler gyrA mutation assay for rapid identification of mutations conferring decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin in multiresistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1443-1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waters, B., and J. Davies. 1997. Amino acid variation in the GyrA subunit of bacteria potentially associated with natural resistance to fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2766-2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White, D. G., L. J. V. Piddock, J. J. Maurer, S. Zhao, V. Ricci, and S. G. Thayer. 2000. Characterization of fluoroquinolone resistance among veterinary isolates of avian Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2897-2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiuff, C., M. Madsen, D. L. Baggesen, and F. M. Aarestrup. 2000. Quinolone resistance among Salmonella enterica from cattle, broilers, and swine in Denmark. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:11-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshida, H., M. Bogaki, M. Nakamura, and S. Nakamura. 1990. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1271-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]