Abstract

Corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) is essential for stress adaptation by mediating hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis, behavioral and autonomic responses to stress. Activation of CRH neurons depends on neural afferents from the brain stem and limbic system, leading to sequential CRH release and synthesis. CRH transcription is required to restore mRNA and peptide levels, but termination of the response is essential to prevent pathology associated with chronic elevations of CRH and HPA axis activity. Inhibitory feedback mediated by glucocorticoids and intracellular production of the repressor, Inducible Cyclic AMP Early Repressor (ICER), limit the magnitude and duration of CRH neuronal activation. Induction of CRH transcription is mediated by the cyclic AMP/protein kinase A/cyclic AMP responsive element binding protein (CREB)-dependent pathways, and requires cyclic AMP-dependent nuclear translocation of the CREB co-activator, Transducer of Regulated CREB activity (TORC). This article reviews current knowledge on the mechanisms regulating CRH neuron activity.

Keywords: Corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH), hypothalamus, stress, HPA axis, transcription, cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB), transducer of regulated CREB activity (TORC), cyclic AMP inducible early repressor ICER, glucocorticoids

1. Introduction

Maintenance of homeostasis requires continuous adaptation to internal and external disturbances or stressors. Adaptive responses include activation of the autonomic nervous system, conducing to increase in cardiovascular and respiratory activity; behavioral changes leading to arousal, defense and escape reactions, and endocrine responses, of which the most important is activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [83]. The later is mostly directed to increase energy availability. In addition, stress results in inhibition of non-essential functions such as gastrointestinal motility and reproduction. These stress responses are coordinated in the brain through neural pathways leading to the release of neurotransmitters and neuropeptides in the hypothalamus and limbic areas.

The 41-amino acid hypothalamic peptide, Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH), stimulates the secretion and synthesis of adrenocorticotropic hormone by the anterior pituitary and is the main regulator of HPA axis activity during stress. Soon after its isolation and characterization in 1981, it became clear that in addition of stimulating ACTH secretion, CRH regulates autonomic and behavioral effects of stress, acting as an important integrator of stress responses [127]. The main source of CRH mediating HPA axis regulation is the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) but in addition, the peptide is present at several extrahypothalamic sites in the brain, most of them related with the limbic system and stress circuitry. This article will review current knowledge on the physiological regulation of the CRH neuron in the hypothalamic PVN, focusing on the molecular mechanisms for activation and termination of the response.

2. The CRH neuron

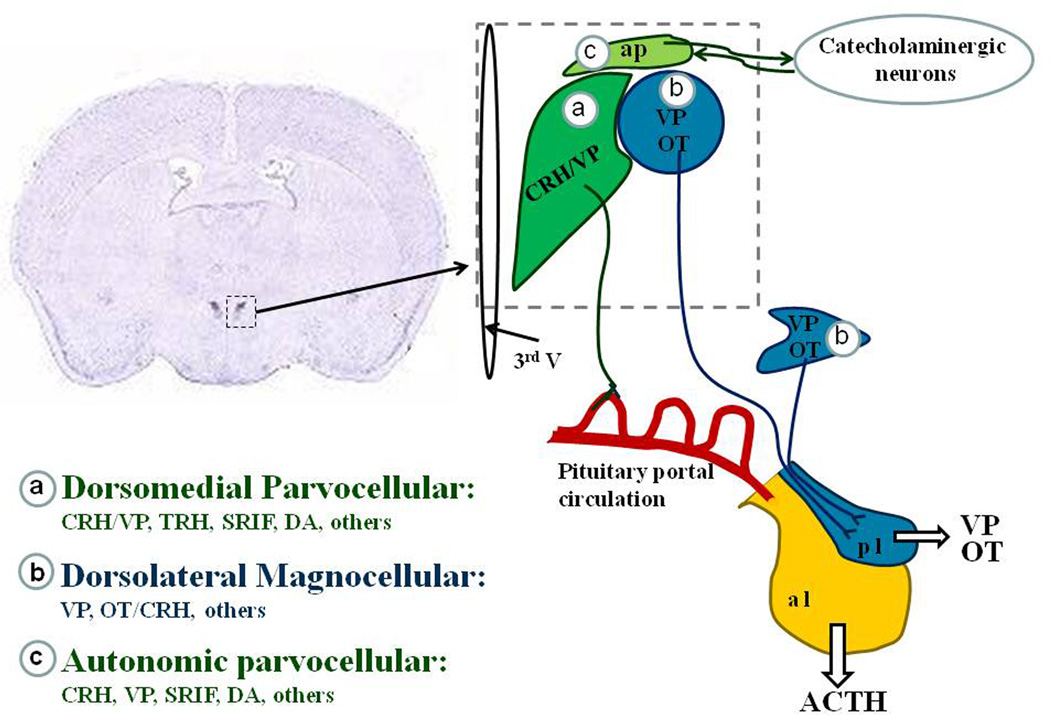

The highest concentration of CRH neurons is found in the hypothalamic PVN [122]. As shown in Figure 1 three major subdivisions have been described in the this nucleus [120]: (a) anterior and medial-dorsal parvocellular CRH neurons with axons projecting to hypophyseal portal capillaries in the external zone of the median eminence; CRH neurons also express small amounts of VP and release VP to the pituitary portal circulation in response to stress. These neurons are classified as parvocellular (from the Latin, “parvus” - meaning small) because of their small size compared with the large size magnocellular neurons, (b) dorsolateral magnocellular vasopressinergic and oxytocinergic neurons with axons projecting to the posterior pituitary through the internal zone of the median eminence. These neurons release peptides to the peripheral circulation. Oxytocinergic neurons also express CRH and respond to osmotic and non-osmotic stressors, while magnocellular vasopressinergic neurons respond to osmotic stimulation but not to stress [17]; (c) autonomic CRH neurons distributed in dorsal, medial-ventral and lateral parvicellular subdivisions, with projections to the brainstem and spinal cord. Neurons at this location express CRH and other neuropeptides and are involved in regulating the sympathoadrenal system [102, 121].

Figure 1. The hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN).

In situ hybridization of CRH mRNA in a coronal section of rat brain at the level of the hypothalamus showing autoradiographic staining in the dorsomedial and autonomic parvocellular subdivisions. A diagram of the different subdivisions of the region indicated by the dotted lines square is shown on the right. (a) The dorsomedial parvocellular division contains corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH) neurons, about 50% co-expressing vasopressin (VP). These neurons project to the external zone of the median eminence and are responsible for the stimulation of ACTH release and synthesis by corticotrophs in the anterior pituitary lobe (apl). This region also contains somatostatin (SRIF), thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH), dopaminergic (DA), growth hormone releasing hormone (GRF) and other peptidergic neurons including enkephalins, dynorphin, galanin, cholecystokinin, angiotensin and neurotensin. (b) The dorsolateral magnocellular subdivision containing VP and oxytocin neurons, projecting to the posterior pituitary lobe (ppl), and responsible for the release of OT and VP to the peripheral circulation. Oxytocinergic neurons co-express small amounts of CRH, which increases during stress and osmotic stimulation. Magnocellular neurons also express dynophin and cholecystokinin. (c) The autonomic parvocellular neurons, containing CRH, and small quantities of most peptides found in the dorsomedial and dorsolateral subdivisions.

In addition to the PVN, CRH mRNA and peptide are also present in other brain regions including limbic and other structures related to the stress response, such as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, the central nucleus of the amygdala, locus coeruleus, cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and dorsal root neurons of the spinal cord [110]. CRH is also present in other neural structures such as chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla and sympathetic ganglia of the autonomic nervous system, and non-neural peripheral organs such as immune cells, skin and gastrointestinal tract [51, 117, 125].

3. Development of the hypothalamic CRH neuron

Studies in rats using in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry have shown CRH mRNA expression in the PVN at embryonic day 17 (E17) [11, 37], and CRH peptide can be first detected at E18 [16, 25]. In the mouse, CRH is first detected in the PVN at E13.5 [52]. Several factors are necessary for the development and differentiation of hypothalamic neurons but the specific factors responsible for differentiation of the CRH neuron are unknown. The most important factor for hypothalamic expression of the CRH gene is the POU-homeodomain protein BRAIN-2 (Brn-2) [41]. This transcription factor is endogenously expressed not only in parvocellular CRH neurons, but also in magnocellular VP and oxytocin neurons. Mice expressing a null mutation of the Brn-2 gene fail to differentiate both CRH neurons and magnocelullar neurons [92, 112]. Other factors involved in hypothalamic development are the homeobox gene Otp [133], and the basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH)-PAS genes Sim1 [87] and ARNT2 [88], the latter two acting as a heterodimer. These factors are upstream of Brn-2 and form part of the gene cascade regulating hypothalamic neuron differentiation [64]). Although these genes are essential for the development of hypothalamic neurons including CRH neurons, and they can induce CRH promoter activity in heterologous cell systems, they do not appear to be involved in the physiological regulation of CRH in vivo.

4. Regulation of the hypothalamic CRH neuron

The activity of the CRH neuron shows different patterns under resting and stress conditions. Activity is low in basal conditions but undergoes marked circadian variations, as judged by day/night changes in immunorective CRH and primary transcript. Circadian variations of CRH neuron activity are driven by the suprachiasmatic nucleus and likely mediate the characteristic circadian pattern of HPA axis activity [20, 95]. Studies in rats have shown that the changes in CRH primary transcript content, reflecting transcriptional activity, are converse to the daily changes in circulating ACTH and corticosterone [134]. It should be noted that CRH mRNA content in the CRH perikarya, as well as peptide content in axon terminals in the median eminence are relatively high. Thus, the circadian rise in HPA axis activity probably depends on CRH release, and that depletion of releasable pools triggers the transcriptional response. The circadian activity of CRH neurons is maintained in the absence of glucocorticoids (in adrenalectomized rats) but sustained increases in glucocorticoids abolish the diurnal rhythm [134].

Stress causes rapid activation of neural pathways afferent to the PVN resulting in rapid CRH release to the pituitary portal circulation followed by increases in CRH transcription and de novo synthesis of the peptide. As described below, the patterns of activation, as well as the neural circuitry utilized, varies according to the type, intensity and duration of the stressor.

4.1 Effects of stress on the expression of CRH and VP by the hypothalamic CRH neuron

As indicated above, about 50% of the medial-dorsal parvicellular CRH neurons responsible for ACTH secretion also express small amounts of VP in basal conditions [8]. The proportion of CRH neurons expressing VP increases markedly during adrenalectomy and chronic stress associated with hyper-responsiveness of the HPA axis [3, 111, 136]. Acute stress induces rapid release of CRH and VP into the pituitary portal circulation [7, 104]. CRH antagonists or antibodies inhibit about 70% of the ACTH response to acute stress, indicating that CRH is largely responsible for HPA axis activation [107]. The association of decreased CRH expression and blunted ACTH responses to stress in conditions such as lactation, or the stress non-responsive period during early in life also supports a primary role for CRH on the ACTH response to stress [115]. The release of CRH and VP is followed by rapid increases in gene transcription, and this is followed by elevation of steady-state mRNA levels 4 h after acute stress. In the stress models studied, CRH gene activation precedes that of the VP gene [43, 57, 75]

During chronic stress, changes in CRH expression in parvicellular neurons depends on the nature of the stress, and these changes parallel the patterns of ACTH response to the repeated stimulus. Psychogenic stressors associated with desensitization of the ACTH responses to the repeated stimulus (restraint, cold exposure) induce CRH transcription and increases in mRNA levels, which are also transient, returning to basal after the first few exposures to the stimulus. However, with systemic paradigms with no desensitization of ACTH responses (repeated i.p. hypertonic saline injection, foot shock, or severe immobilization), CRH transcription and elevations in mRNA occurs after each stress exposure up to 14 or more days [4]. This suggests that preserved capacity of the CRH neuron to respond to stress is required to maintain ACTH responses during a repeated homotypic stress. Another characteristic of chronic stress is that irrespective of whether or not there is habituation to the repeated homotypic stressor, there is generally an increased CRH transcription and HPA axis responsiveness to a novel or heterotypic stressor [4, 76], suggesting the development of plasticity changes that facilitate the response to stress.

In contrast to CRH, VP expression in the parvocellular CRH neurons is increased in all chronic stress models studied, as shown by increases in VP mRNA and primary transcripts in parvicellular neurons, and irVP in the external zone of the median eminence [12, 28, 44, 78]. This preferential expression of VP over CRH suggested for a long time that VP has a primary role during adaptation of the HPA axis to long-term stimulation [3]. However, studies using pharmacological or genetic ablation of V1bR have shown that VP is required for full ACTH responses to some stressors, though reductions in ACTH are relatively minor since corticosterone responses are usually normal [6, 108]. Similarly, the sensitization of ACTH responses to a novel stress observed during chronic stress is preserved after pharmacological blockade of V1b receptors [18]. The overall evidence indicates that VP is essential for full ACTH (but not corticosterone) responses to stress, and that CRH is the main regulator of HPA axis activity during acute and chronic stress.

The activity of the CRH neuron is controlled by a number of stimulatory and inhibitory neural pathways, as well as peripheral hormonal influences. While negative feedback of glucocorticoids plays a predominant role under basal conditions, stimulatory neural pathways activate the CRH neuron during stress increasing CRH peptide release and gene transcription in spite of the rise of glucocorticoids.

4.2 Neural regulation of hypothalamic CRH neurons

A large body of evidence indicates that in basal conditions the CRH neuron is under the inhibitory influence of GABAergic inter-neurons located in the periventricular region of the hypothalamus [23, 46]. This is supported by anatomical studies showing rich GABAergic innervation of CRH neurons [89], and the presence of GABA A receptor subunits in hypophyseotropic CRH neurons [24], and pharmacological studies showing stimulation of CRH expression by GABA antagonists in organotypic cultures [10] and stimulation of HPA axis activity by microinjection of GABA agonists in the PVN and stimulation following antagonist injection [23].

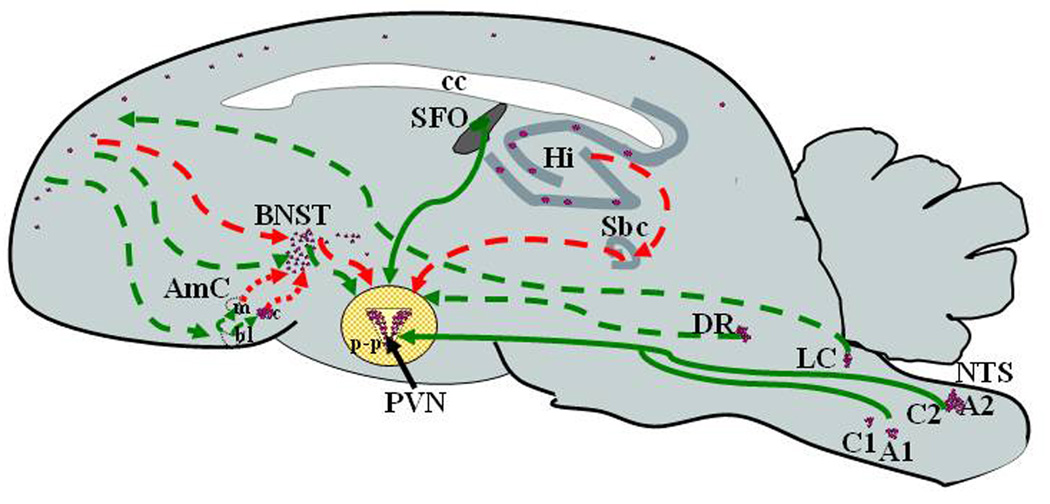

With stressful stimuli, sensory information is either directly transmitted to the PVN, or integrated by the limbic system and conveyed to CRH neurons in the PVN via complex monoaminergic and peptidergic neural pathways depending on the nature, intensity and duration of the stressor. Systemic physical and metabolic stressors requiring an immediate response, such as loss of blood volume, immune challenge, pain and hypoglycemia, utilize monosynaptic ascending pathways from the brain stem and spinal cord, with direct projections to the PVN [45]. These projections originate in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and C1 and C3 are mostly noradrenergic and adrenergic and stimulate CRH neurons by acting via alpha adrenergic receptors in the CRH neuron (Figure 2). In addition to direct synapses with CRH neurons, brain stem pathways interact with limbic areas in the brain, including the dorsal raphe (which controls serotoninergic activity) the dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (DMH) (which modulates autonomic activity) and the forebrain. Catecholaminergic and non-catecholaminergic neurons in the NTS projecting to the PVN express other neuropeptides, such as NPY, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), inhibin-β, somatostatin and enkephalin. Some of these peptides, such as GLP-1 and NPY, have been shown to influence HPA axis activity by acting on the CRH neuron [91, 119, 131].

Figure 2. Neural pathways regulating the CRH neuron in the PVN during stress.

CRH neurons depicted as purple dots are mainly concentrated in the PVN but also present in catecholaminergic neurons of the brain stem, frontal cortex, central nucleus of the amygdala (c), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and other limbic areas. Systemic stressors (blood loss, pain, hypoglycemia) signal through direct (solid green lines) projections to the CRH neuron from A2 and C2 catecholaminergic neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), and A1 and C1 adrenergic neurons in the ventrolateral medulla. Signals from psychogenic stressors utilize multisynaptic pathways from sensory organs, the locus coeruleus (LC) and brain stem nuclei through limbic structures, including the prefrontal cortex, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), and amygdala. This pathways interact with the CRH neuron indirectly (doted lines) through glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons in the peri-PVN area (p-p), which make direct synapses with the CRH neuron. The hippocampus sends inhibitory signals through the prefrontal cortex and subiculum (Sbc). The dorsal raphe projects serotoninergic signals to the peri-PVN area and directly to the CRH neuron. In addition, hormonal signals from the periphery interact with the subfornical organ (SFO), a circumventricular organ outside the blood brain barrier, which has direct projections to the CRH neuron.

In contrast to systemic stress, responses to psychogenic stressors utilize complex polysynaptic pathways, including the participation of several limbic structures, the most important being the medial prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Figure 2). Dorsomedial and prelimbic areas of the frontal cortex have inhibitory projections for the HPA axis and autonomic activity, while the ventromedial region is stimulatory, initiating HPA axis and autonomic responses to psychogenic stress [45, 140]. The prefrontal cortex inputs are mediated through interconnections with other limbic structures, such as the hippocampus, ventral subiculum and the amygdala.

The hippocampus is predominantly inhibitory to the HPA axis and autonomic responses to psychogenic stressors. Hippocampal inputs reach the PVN indirectly through multi-synaptic pathways via the ventral subiculum for the HPA axis, and the prefrontal cortex for autonomic activity. These regions in turn innervate the periventricular region containing glutamatergic and GABAergic projections to CRH neurons [140]. The hippocampus reduces the duration of HPA axis responses rather than the magnitude, as hippocampal or ventral subicular lesions prolong corticosterone responses to psychogenic stress.

The central nucleus of the amygdala, which expresses high levels of CRH, is essential for behavioral responses (especially fear) and for integrating autonomic responses during psychogenic stress. The basolateral and medial amygdala have positive modulatory actions on HPA axis activity, as lesions of these regions reduce responses to psychogenic stressors.

The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) acts as an integrative center for limbic inputs to the PVN, and in fact most limbic inputs to the PVN relay in neurons of this nucleus. Lesion studies have shown that the anteroventral and anterolateral sub-regions relay excitatory pathways, while the posteromedial BNST conveys inhibitory signals. BNST inputs to the PVN are indirect, involving synapses with periventricular GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons. Most neurons in the BNST are GABAergic (inhibitory); thus, excitatory signals are likely to occur through inhibition of GABAergic periventricular interneurons [19, 82, 126, 139].

Responsiveness of the HPA axis undergoes adaptation during chronic or repeated stress and there is usually hypersensitivity to a novel stress [3]. This requires neuronal plasticity with recruitment of new neural pathways not normally involved in the acute stress response. In this regard, it is clear that exposure to many chronic stress paradigms (but not all) decreases the number of dendritic spines in the hippocampus and frontal cortex [19, 82]. With repeated restraint stress (but not with variable inescapable stress) there are increases in dendritic projections and spines in the amygdala, which are the converse to those observed in the hippocampus [130]. Neuronal plasticity at these sites and other brain regions controlling HPA and autonomic responses to stress, are likely to mediate changes in HPA axis responsiveness typical of chronic stress. For example, increased inhibitory synaptic activity in the amygdala could mediate habituation to homotypic repeated stressors. These changes are transient and revert to basal conditions 10 to 14 days after termination of the stress. Another important nucleus involved in the regulation of HPA axis responsiveness during chronic stress is the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus, serving as a relay center for both stimulatory and inhibitory inputs. While lesions of this nucleus have no effect on the acute stress response, they do prevent habituation to a homotypic repeated stress, as well as sensitization to a novel stimulus during repeated stress [13, 14].

4.3 Regulation of the CRH neuron by peripheral influences

Stress responses are modulated by peripheral hormonal signals including a number of peptides, sex steroids, and, most importantly adrenal glucocorticoids. Peripheral factors such as cytokines and the peptide hormones, angiotensin II, prolactin and leptin, cannot cross the blood brain barrier, but can signal in the brain through neural pathways from the circumventricular organs, structures which are outside the blood brain barrier. These include the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), subfornical organ (SFO), the lamina terminalis containing the median preoptic nucleus (MPO), and the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (OVLT), and the choroid plexus [85]. All these structures express levels of angiotensin II receptors which mediate the central actions of peripheral angiotensin II [86]. This peptide is the end product of the renin-angiotensin system, which is stimulated during stress as a consequence of adrenergic stimulation of renin production by the kidney. Elevations in circulating angiotensin II stimulate the HPA axis activity through direct neural angiotensinergic pathways from the SFO to the PVN. Angiotensin can stimulate CRH release via type 1 receptors located in CRH neurons [2]. Angiotensin II receptors in the NTS and lamina terminalis are important in the regulation of cardiovascular homeostasis during alterations of blood volume, and water and electrolyte balance [84].

There is evidence that peripheral prolactin is taken up by receptors in the choroid plexus and acts in the brain [81]. Prolactin has inhibitory effects on HPA axis activity, and it is believed that the peptide partially mediates the hypo-responsiveness of the HPA axis during lactation [124]. In addition, the arcuate nucleus is also sensitive to peripheral signals, such as changes in blood glucose and leptin, and conveys metabolic signals to the PVN [54, 124]. Cytokines are potent stimulants of HPA axis activity by acting directly in the pituitary and by stimulating CRH release and transcription. Cytokines access the PVN through the circumventricular organs as well by stimulating prostaglandin synthesis and nitric oxide production by endothelial cells of capillaries in the PVN.

4.4 Regulation of the CRH neuron by glucocorticoids

Removal of endogenous glucocorticoid production by adrenalectomy highly exacerbates ACTH responses to stress, and chronic glucocorticoid administration has the opposite effect [77, 79]. These changes in HPA axis responsiveness parallel changes in CRH mRNA levels indicating that the CRH neuron is one of the targets of the feedback mechanism [26, 66]. Glucocorticoids clearly modulate the responsiveness of parvocellular neurons to stress, including transcriptional activation [77, 79]. For example, a minor stressor, such as intraperitoneal (ip) vehicle injection, causes marked increases in CRH and VP primary transcript expression in adrenalectomized rats, while having no effect in intact rats [77]. It is also clear that administration of glucocorticoids to intact rats inhibits ACTH secretion and basal levels of hypothalamic CRH mRNA levels and markedly reduces CRH heteronuclear RNA responses to stress [5, 100].

The site of action of glucocorticoid feedback is still a matter of controversy, but it is becoming clear that glucocorticoids inhibit CRH neuron activity at multiple sites. Microdialysis studies have shown that peripheral glucocorticoid administration causes marked decreases in norepinephrine release in the PVN, suggesting that glucocorticoids inhibit the activity of stimulatory neural pathways to the PVN [99]. There is evidence that glucocorticoid receptors in limbic forebrain structures play an important role in basal HPA axis activity and in the feedback inhibition to psychogenic but not to systemic stressors. Both glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) are highly expressed in the hippocampus. In contrast to the abundance of high affinity MR in the hippocampus, other forebrain limbic structures such as the prefrontal cortex and amygdala contain mostly GR and are sensitive to higher glucocorticoid levels observed during the circadian peak and stress [65]. Glucocorticoid implants in the medial frontal cortex inhibit HPA axis responses to psychogenic stressors [30]. On the other hand, mice with selective deletion of the GR in the cortex, hippocampus and amygdala have elevated basal glucocorticoids, prolonged corticosterone responses to psychogenic stress, and reduced inhibitory effect of exogenous glucocorticoids on HPA axis activity [9]. In contrast, overexpression of GR in the forebrain results in reduced ACTH and corticosterone responses to stress.

Although the evidence above suggest that forebrain GR receptors are sufficient for feedback inhibition to psychogenic stressors, it is also clear that part of feedback inhibition occurs at the level of the PVN. GR are also abundantly expressed in the PVN including in CRH neurons [32, 68], and direct injections of glucocorticoids in the PVN clearly decrease CRH mRNA [40, 55, 68, 109]. Also the recent demonstration that glucocorticoid administration was able to suppress CRH hnRNA responses to stress but with preserved c-fos responses, supports a direct inhibition of CRH transcription without interruption of stimulatory afferents [35]. Another potential mechanism of inhibition of the CRH neuron by glucocorticoids is regulation of receptors and other regulatory proteins in the neuron. In this regard, adrenalectomy increases and glucocorticoid administration decreases the content of alpha adrenergic receptors in the PVN [27], and in vitro studies have shown switching in adrenergic receptor from α1 to α2 in hypothalamic sections after incubation with glucocorticoids [33].

In addition to the genomic effects of glucocorticoids mediated by classical GR, electrophysiological studies have shown rapid inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids on CRH neurons probably mediated by non-genomic mechanisms. According to these studies, glucocorticoids stimulate synthesis and release of endocannabinoids from CRH neurons, which in turn inhibit presynaptic glutamatergic terminals resulting in inhibition of CRH neuron activity. The effects can be produced by albumin-coupled glucocorticoids, indicating that the steroid is acting at the plasma membrane level [29]. This putative plasma membrane receptor has not been isolated or characterized and it could correspond to the traditional receptor associated to membrane proteins.

4.5 Autoregulation of the CRH neuron by CRH and other neuropeptides

There is evidence that CRH can regulate its own expression in CRH neurons of the PVN. Intracerebroventricular injection of low doses of CRH, devoid of ACTH releasing activity on their own, markedly potentiates ether-stimulated ACTH secretion suggesting a positive feedback effect by CRH [29, 98]. While some of these effects could be indirect via activation of CRH-R in nuclei with interconnections to the PVN, such as other hypothalamic nuclei, the amygdala, locus coeruleus and nucleus of the solitary tract, reports of inhibition of feeding behavior and increases in sympathetic outflow after local application of CRH in the PVN suggest a direct effect [15, 58].

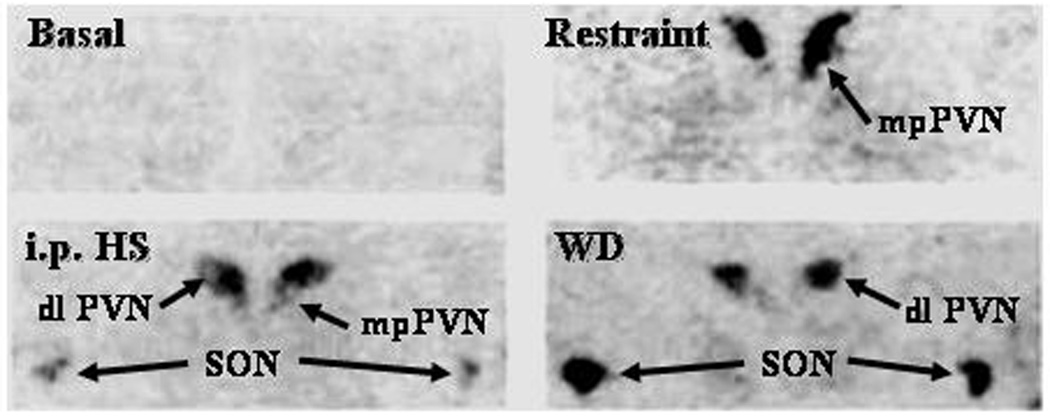

The existence of a direct autoregulatory role for CRH in the CRH neuron is strongly supported by the demonstration that stress induces CRHR1 mRNA and CRH binding in the PVN. CRH receptors are very low in basal conditions but increase markedly following stress [74, 79, 106]. The topographic pattern of CRHR1 expression is stress specific (Fig 3), with increases in the parvocellular division of the PVN after physical-psychological stress (repeated immobilization, ip hypertonic saline injection, acute immune challenge by lipopolysaccharide injection), and in the magnocellular PVN and in the supraoptic nuclei during osmotic stimulation [74]. The stress-specific induction of CRHR1 in CRH neurons suggests that CRH plays an autoregulatory role on its own expression. Supporting this possibility, icv injection of a CRH antagonist attenuates the increases in CRH mRNA in the PVN induced by acute immobilization [49]. CRHR1 is coupled to adenylate cyclase, thus, its activation by locally secreted CRH would provide a source of cyclic AMP, which is necessary for activation of CRH transcription.

Figure 3. Stress induces CRH receptor mRNA in the PVN and SON in a stimulus-specific manner.

In situ hybridization images for CRHR1 mRNA in hypothalamic sections of control rats, 4h after 1h restraint stress, or i.p. hypertonic saline injection (ipHS), or osmotic stimulation by 60 h water deprivation (WD). Levels of CRHR1 mRNA in the PVN are very low in basal conditions and increased markedly in the dorsomedial parvocellular region of the PVN (corresponding to CRH neurons) after a psychosomatic stress (restraint) and in the dorsolateral magnocellular PVN and SON following osmotic stimulation (WD). Hypertonic saline injection (i.p.), a combined painful stress and osmotic stimulation induces CRHR1 mRNA in both parvocellular and magnocellular neurons.

Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase Activating Polypeptide (PACAP) is secreted in the brain during stress and could provide an additional cyclic AMP stimulator in the CRH neuron. Light and electron microscopy studies have shown abundant PACAP innervation making contact with CRH perikarya [36, 63]. PACAP has been shown to stimulate CRH promoter activity in reporter gene assays [50], and recent studies have shown that PACAP knockout mice have shorter elevations in plasma corticosterone and absent CRH mRNA responses to restraint stress [118].

In addition, VP and OT, peptides produced in magnocellular neurons, have been reported to inhibit CRH secretion and expression. Intracerebroventricular injection of VP causes dose dependent attenuation of the release of CRH to the pituitary portal circulation in urethane anesthetized rats, and conversely, VP antagonists or antibodies have the opposite effect [105]. Central OT administration inhibit HPA axis and CRH mRNA responses to stress [93, 137], but this inhibitory effect is evident only in the presence of high estrogen levels [97]. Oxytocin could inhibit CRH expression directly in the CRH neuron but the finding that OT attenuates c-fos mRNA in forebrain regions associated with modulation of HPA axis activity indicates that the effect is at least in part indirect [138].

5. Signaling pathways regulating the CRH neuron

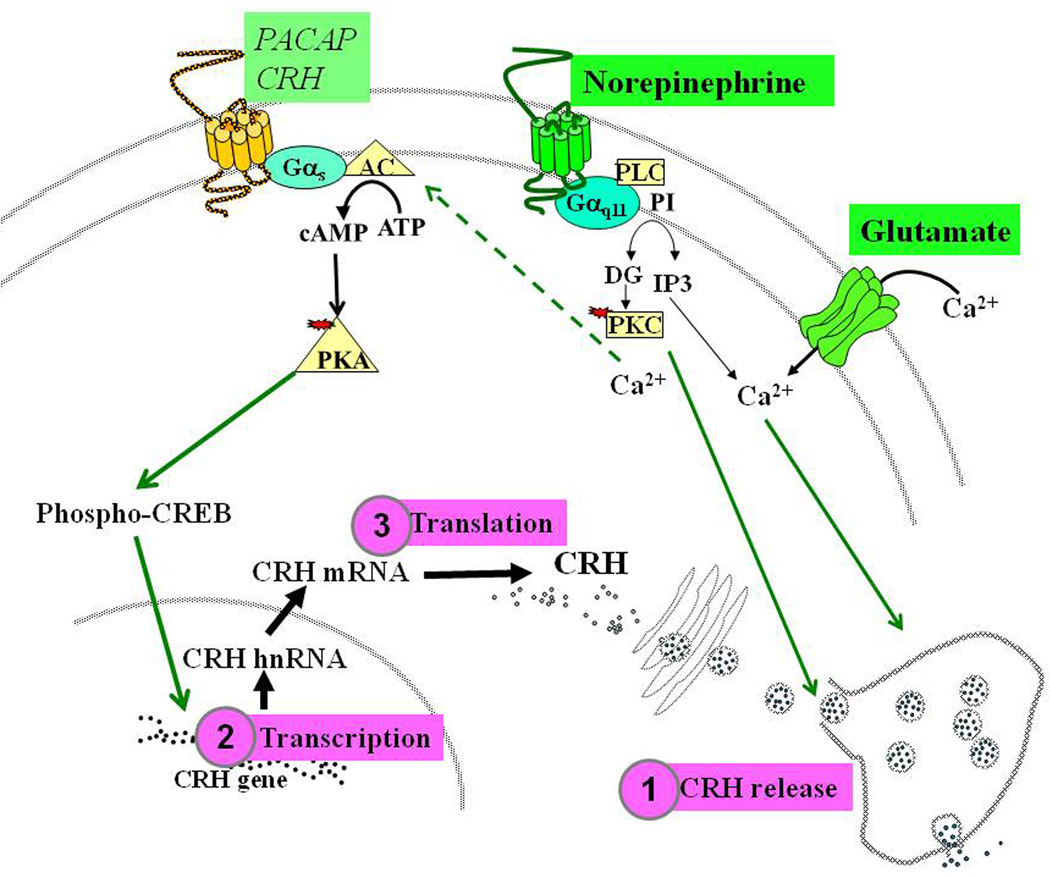

Afferent inputs to the PVN trigger the release of a number of neurotransmitters and neuropeptides such as noerepinephrine, glutamate, GABA, angiotensin II, PACAP, CRH itself and other peptides. These factors interact with receptors in the CRH neuron triggering intracellular signal-transduction pathways (Figure 4). The main neurotransmitters released in the PVN during stress are norepinephrine and glutamate [42, 101]. Norepinephrine acts on alpha adrenergic receptors which are coupled to the guanyl nucleotide binding protein q/11 and phospolipase C, thus increasing intracellular calcium and protein kinase C activity [62]. Norepinephrine can also activate beta-adrenergic receptors with lower affinity, but in vivo and in vitro evidence suggest that alpha- but not beta-adrenergic receptors mediate the direct stimulatory effect of norepinephrine in CRH neurons. In situ hybridization studies using receptor subtype specific probes have shown that the subtype present in CRH neurons is the alpha 1-adrenergic receptor [27, 103]. Glutamate interacts with NMDA and GluR5 receptors located in the CRH neuron leading to increases in intracellular calcium and neuronal excitability [31, 139]. GluR5 receptors are located in CRH containing terminals in the external zone of the median eminence. Glutamate is a major excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system and it is likely to mediate the rapid increases in CRH release into the pituitary portal circulation.

Figure 4. Neurotransmitters and signaling transduction systems regulating the CRH neuron.

Stimulation of afferent neural pathways to the PVN results in the release of norepinephrine and glutamate. Norepinephrine acts on alpha adrenergic receptors which are coupled to the guanyl nucleotide binding protein q/11 (Gq11) and phospolipase C (PLC), resulting in increase in intracellular calcium (Ca2+) and protein kinase C (PKC) activity. Glutamate interacts with NMDA and GluR5 receptors leading to increases in intracellular calcium. These pathways are likely to mediate rapid CRH release within seconds  . Release is follow by activation of CRH transcription within minutes

. Release is follow by activation of CRH transcription within minutes  , a process which requires cyclic AMP. The mechanism for cyclic AMP production is not clear but it could involve activation of CRHR1 or PACAP receptors, which are coupled to adenylate cyclase, or/and activation of a calcium dependent adenylate cyclase (indicated by the broken arrow). Transcription leads to increases in mRNA levels and translation to the CRH precursor protein

, a process which requires cyclic AMP. The mechanism for cyclic AMP production is not clear but it could involve activation of CRHR1 or PACAP receptors, which are coupled to adenylate cyclase, or/and activation of a calcium dependent adenylate cyclase (indicated by the broken arrow). Transcription leads to increases in mRNA levels and translation to the CRH precursor protein  . The signaling mechanisms controlling translation and processing of the precursor protein to CRH have not been fully elucidated.

. The signaling mechanisms controlling translation and processing of the precursor protein to CRH have not been fully elucidated.

A large body of evidence indicates that cyclic AMP is a major regulator of the CRH neuron, and that cyclic AMP-dependent signaling is essential for transcriptional activation [1, 73, 96, 113]. Microinjection of the cyclic AMP analog 8-Br-cyclic AMP in the PVN causes rapid elevations in plasma ACTH suggesting that the cyclic nucleotide also induces CRH release [48]. However, neither norepinephrine nor glutamate stimulates cyclic AMP production. Since cyclic AMP signaling is essential for transcriptional activation an important question is the source of the stimulation of cyclic AMP production during stress. Possible stimulants acting upon receptors coupled to adenylate cyclase are CRH and PACAP. As described above (see 4.5), there are nerve terminals and receptors for both peptides in the CRH neuron [67, 74, 106, 129]. An additional mechanism for cyclic AMP production it is that the increases in cytosolic calcium, secondary to alpha –adrenergic or glutamate receptor stimulation could stimulate a calcium-dependent adenylate cyclase. In situ hybridization studies have shown the presence of the calcium-dependent adenylate cyclase 8 in the PVN of the mouse brain, suggesting that calcium could mediate increases in cyclic AMP [22]. While the exact mechanism responsible for cyclic AMP stimulation in the CRH neuron remains to be elucidated, in vitro experiments have shown that small increases in cyclic AMP are sufficient for activation of the CRH promoter [96]. In addition, calcium phospholipid-dependent pathways potentiate the ability of small elevations of intracellular cAMP to activate CRH transcription, providing a mechanism by which non-cAMP dependent regulators can modulate CRH gene expression [73].

6. Regulation of CRH transcription

Activation of CRH neurons during stress leads to rapid release of stored peptide (within seconds) an event which is coupled to the novo synthesis of peptide in order to restore releasable pools in the nerve endings of the median eminence. Synthesis of the precursor involves activation of gene transcription with formation of primary transcript or heteronuclear RNA, within minutes, followed by splicing of the intron and formation of mature mRNA, which starts to increase within an hour following the stimulus. Since in basal conditions there are relatively high levels of mature mRNA in the perikarya of the CRH neuron, it is likely that translation is initiated independently of the formation of new transcript. Thus, the rapid transcriptional activation is not needed for the immediate secretory response but it is important for restoring mRNA utilized for translation of new pro-CRH.

While activation of CRH transcription is important for maintaining adequate CRH levels needed for the integrated stress response, limiting the activation is also essential in order to prevent deleterious affects of excessive CRH production. The sections below will discuss current knowledge on the mechanisms of activation and limitation of the CRH transcription.

6.1 The CRH promoter

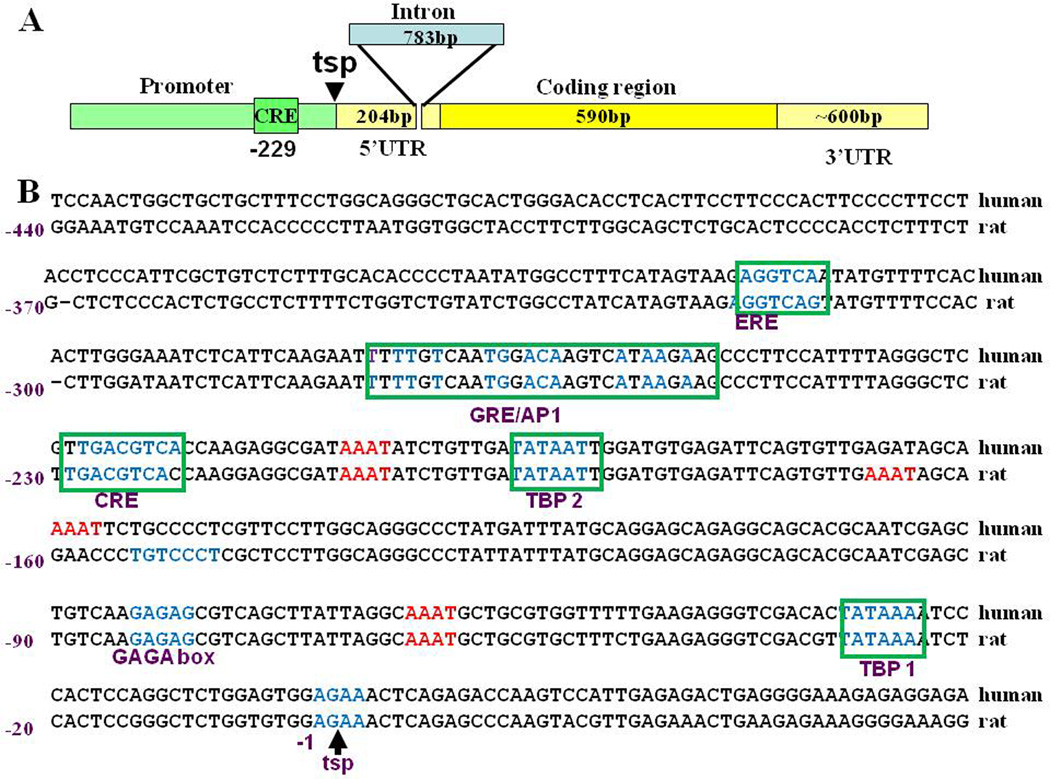

The CRH gene has two exons and one short intron located in the 5’ untranslated region. The sequence of the proximal 5’flanking region of the CRH gene is highly conserved between species and contains two TATA binding protein sites and a number of responsive elements, of which the most prominent functionally is a cyclic AMP responsive element (CRE) at position −247 [113] (Figure 5). Other element characterized in heterologous systems in vitro, is an atypical GRE/AP1 element located at –−249 to −248, which has been described to bind GR and mediate transcriptional inhibition [80]. There are also half estrogen responsive elements (ERE), which have been reported to mediate transcriptional stimulation by estrogen [128]. However, a more recent report shows that estrogen receptors alpha and beta can modulate CRH transcription by interacting with the transcriptional complex at the CRE [60]. In addition, the proximal promoter contains a number of potential sites for the POU homeodomain protein, Brn-2 [41] which is required for the development of CRH neurons (see section 3).

Figure 5. Structure of CRH transcript and 5’flanking region or the CRH gene.

As shown in A, the CRH gene has two exons (shown in yellow) and one intron (shown in blue) located in the 5’ untranslated region (5’UTR). The 5’ flanking region is shown in green and emphasizes the cyclic AMP response element (CRE) at −229, which is essential for transcriptional activation and inhibition. A comparison of the sequences and response elements in the 5’ flanking region showing the high homology between human and rat is depicted in B. In both species the promoter has 2 TATA boxes or TATA binding protein elements (TBP), the CRE at −229, a combined glucocorticoid and AP1 response element (GRE/AP1), and an a half estrogen response element (ERE). These elements have been characterized using reporter gene assays. In addition, there are several potential sites for the POU homeodomain protein, Brn-2, which is essential for CRH neurons differentiation (indicated in red), Several other motifs present in the promoter have not been functionally characterized.

Most studies focus on the 5’flanking region but a neuron-restrictive silencing element, (RE-1/NRSE), identified in the intron of the CRH gene, is likely to mediate repression of CRH transcription in non-neuronal tissues [114]. Activation of the CRH neuron during stress is associated with induction of a number of immediate early genes, such as c-fos, Fra-2, zip-268/Egr-1 and NGF1B, as well as phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of CREB and the MAP kinase ERK [53, 56, 135]. This suggests that these transcription factors have a role in the regulation of CRH transcription. However, with the exception of CREB, the exact interaction of these factors with response elements in the CRH promoter remains to be elucidated.

6.2 Positive regulation of CRH transcription

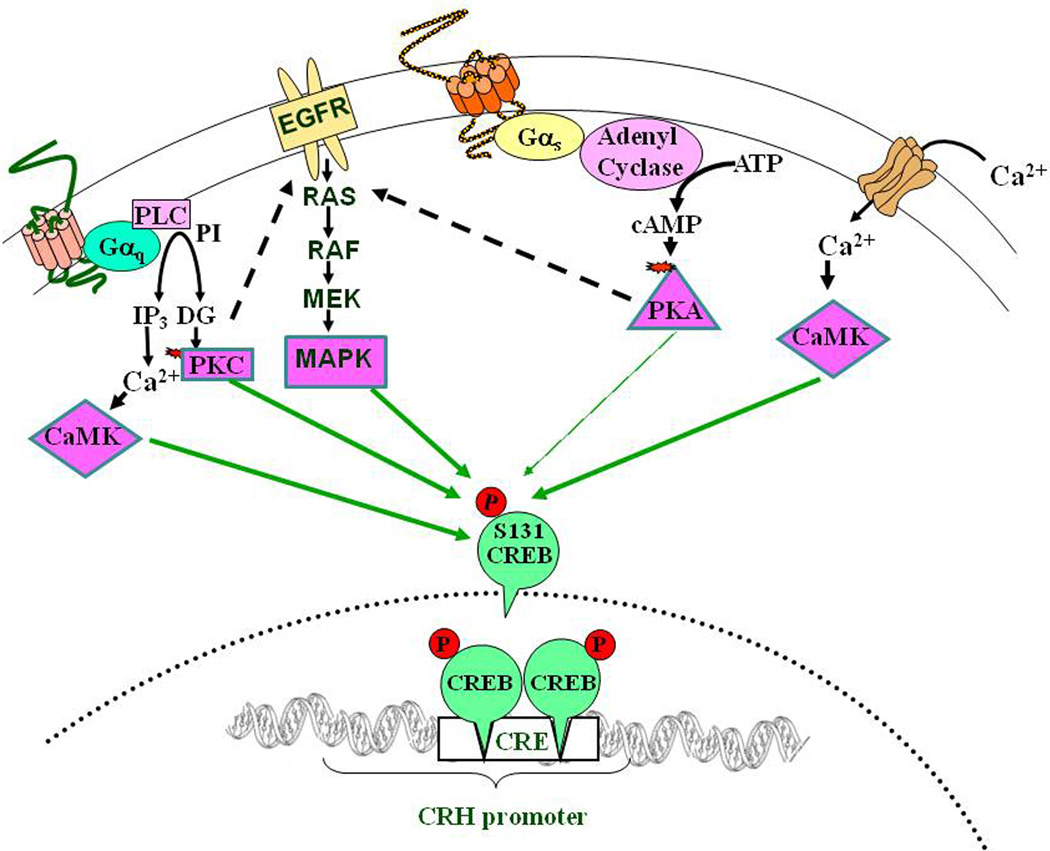

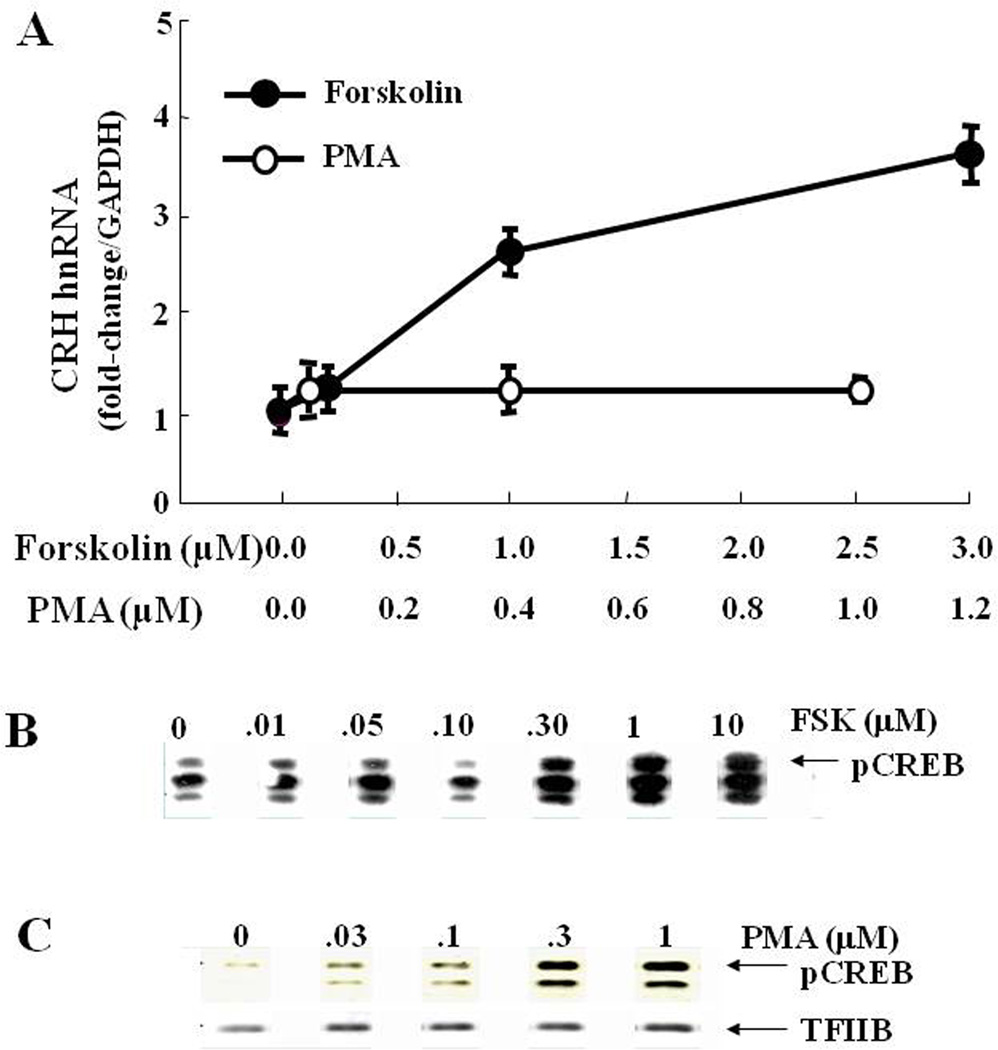

It has long been accepted that activation of CRH transcription depends on cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) dependent pathways leading to recruitment of phosphorylated cAMP response element binding protein (pCREB) by the cAMP response element (CRE) of the CRH promoter [113]. It is clear that the CRE in the CRH promoter is essential for cyclic AMP dependent and independent regulation of CRH transcription [38, 94]. Also, CREB is required for CRH promoter activation since the CREB dominant negative, A-CREB, blunts the stimulatory effect of forskolin on CRH promoter activity [73]. Although the requirement of the CRE and CREB for activation of transcription is conclusive, it is also clear that a large number of signaling pathways lead to CREB phosphorylation (Figure 6), but in the absence of cyclic AMP, CREB is not sufficient for stimulating CRH transcription [73]. Treatment of the hypothalamic-derived neuronal cell line (4B cells), or hypothalamic primary neuronal cultures, with either the phorbol ester phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA, a protein kinase C activator) or forskolin (an adenylate cyclase activator) led to CREB phosphorylation. However, only forskolin treatment was able to stimulate CRH transcription, measured in reporter gene assays in 4B cells or induction of primary transcript in primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons [73] (Figure 7). A similar situation has been suggested in experiments in rats in which microinjection of both 8-bromo-cAMP and the phorbol ester, TPA (protein kinase C stimulator) in the PVN increase plasma ACTH and pituitary POMC mRNA levels, but only cAMP augments CRH mRNA levels [48]. These studies strongly suggest that activation of CRH transcription depends not only on CREB phosphorylation but it requires interaction with a co-activator, the activation of which requires cyclic AMP. Recent studies have identified the CREB co-activator, Transducer of Regulated CREB Activity (TORC), also known as CREB-regulated transcription co-activator (CRTC), as the missing link in the regulation of CRH transcription.

Figure 6. Signaling pathways conducing to CREB phosphorylation in CRH neurons.

Activation of G protein coupled receptors, receptor and voltage activated calcium channels shown in Fig 4, leads to increases in intracellular calcium, and other second messengers such as inositol 3 phosphate (IP3), diacylglycerol (DG) and cyclic AMP (cAMP) and consequent activation of calcium calmodulin dependent protein kinase (CaMK), protein kinase C (PKC), protein kinase A (PKA) and transactivation of the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK). All of these protein kinases can activate Cyclic AMP Responsive Element Binding protein (CREB), by phosphorylation. However, CREB phosphorylation alone is not sufficient to initiate CRH transcription.

Figure 7. Phosphorylation of CREB is not sufficient to initiate CRH transcription.

The dose responses for the effect of the stimulator of adenylate cyclase, forskolin and the phorbol ester, PMA, on CRH hnRNA in primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons show dose dependent increases after incubation for 45 min with forskolin but not after incubation with PMA. CRH hnRNA was measured by qRT-PCR using intronic primers (A). Western blot analyses of phospho-CREB content in nuclear proteins hypothalamic cells, 4B, incubated for 30 min with forskolin (B) or PMA (C).

The TORC family, comprising TORC 1, 2 and 3, was discovered and characterized in 2003 by two groups independently searching for proteins that interacted with CREB [21, 47]. TORC potentiates the transcriptional activity of CREB by binding to its dimerization domain and facilitating recruitment of the transcriptional complex [21, 123]. In basal conditions, TORC is in the cytoplasm in a phosphorylated state and bound to the scaffolding protein 14-3-3. TORC phosphorylation is mediated by members of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) family of Ser/Thr protein kinases, including salt-inducible kinase, (SIK). Protein kinase A inactivates these kinases, thus preventing TORC phosphorylation and allowing its release from 14-3-3 and translocation to the nucleus, where it interacts with CREB. In addition to the cyclic AMP-dependent inhibition of the kinase, the calcium/calmodulin dependent phosphatase, calcineurin, dephosphorylates and therefore facilitates TORC activation. TORC 1, 2 and 3 are distributed in a tissue specific manner in the periphery, where they have important roles in energy metabolism, and in different areas of the brain. While TORC 1 is the most abundant and widely distributed in the brain and all three TORC subtypes are present in the PVN (Watts A, Sanchez-Watts G, Liu Y and Aguilera G, submitted), there is evidence that TORC 2 is co-localized in CRH neurons [71], and that TORC 2 may be the major player in the regulation of CRH transcription [69].

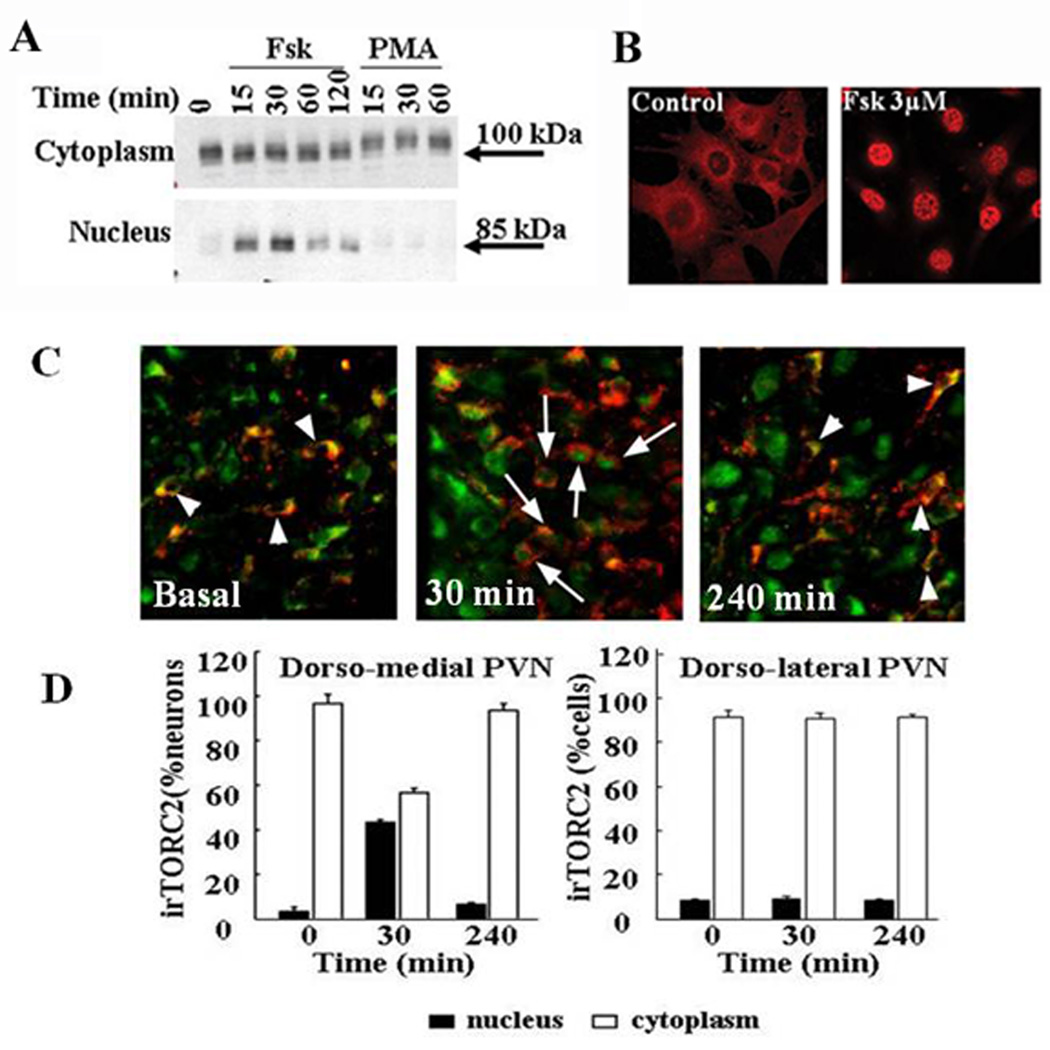

Recent studies provide evidence that TORC is necessary for forskolin stimulated CRH promoter activity and CRH gene expression in hypothalamic neurons. First, all three isoforms of TORC proteins (TORC1, TORC2, and TORC3) are expressed in 4B cells, and in hypothalamic neurons with TORC2 exhibiting the highest basal level of expression. In unstimulated hypothalamic neurons, TORC is localized primarily in the cytoplasm and rapidly translocated to the nucleus after treatment with the stimulator of adenylate cyclase, forskolin. The migration of the TORC 2 protein band in the western blot is slightly accelerated after forskolin treatment, consistent with rapid dephosphorylation [132]. It is noteworthy that similar to the findings on CRH transcription, the phorbol ester, PMA, failed to induce nuclear translocation of TORC and led to apparent TORC hyperphosphorylation, judging from the slightly delayed migration of TORC in the gel. (Figure 8). Studies on the role of the different TORC isoforms on CRH transcription in vivo have been more difficult because of the lack of availability of antibodies suitable for TORC 1 and 3 immunostaining. However, studies using a TORC 2 antibody demonstrated specific TORC 2 immunostainining in the dorsolateral (magnocellular) and dorsomedial (parvocellular) regions of the PVN [71]. While staining was mostly cytosolic in basal conditions, there was a marked increase in nuclear irTORC 2 in the parvocellular region after 30 min restraint, concomitant with increases in CRH hnRNA levels. Levels of nuclear irTORC 2 and CRH hnRNA had returned to basal 4h after stress. Double staining immunohistochemistry showed TORC 2 co-staining in 100% of CRH neurons, and nuclear translocation following 30 min restraint in 61%. Cellular distribution of TORC 2 in the dorsolateral PVN was unaffected by restraint (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Time course of the effect of forskolin and PMA on nuclear translocation of TORC2 in 4B cells Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins from cells treated with vehicle (0.01% DMSO 0), forskolin (Fsk), or PMA were subjected to Western blot analysis for TORC2. Data points are the mean ± SE of the values obtained in three experiments, expressed as fold-change from basal values in vehicle treated cells (A). Immunofluorecence staining of TORC 2 in 4B cells treated for 30 min with vehicle or forskolin (B). Co-localization of TORC 2 and CRH in parvocellular neurons of the hypothalamic sections of control rats, and in rats subjected to restraint stress for 30 min or 180 min after 1h restraint (240 min) (C). The quantitative analysis of the number of cells showing nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in the dorsomedial (parvocellular) and dorsolateral (magnocellular) regions of the PVN is shown in (D). Bars represent the mean and SE of measurements expressed as percent of cytosolic and nuclear location per total number of cells were counted in each animal in three rats. *P < 0.01 higher than nuclear staining in basal (time 0), or 3 h after termination of 1 h of stress (240 min). #P < 0.01 lower than cytoplasmic staining in basal, or 3 h after termination of 1 h of stress (240 min).

In addition to demonstrating nuclear translocation of TORC, in vitro and in vivo studies showed interactions of TORC with CREB, as well as the interaction of TORC with the CRH promoter [69, 71]. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments using 4B cells demonstrated a direct association of TORC2 protein with CREB after stimulation of cyclic AMP-dependent pathways by forskolin, but not after stimulation with the phorbol ester, PMA. Moreover, chromatin immunoprecipitation studies, showed increased association of TORC2 and CREB proteins with the CRH promoter after treatment of 4B cells with forskolin but not with PMA [69]. Similarly, immunoprecipitation of hypothalamic chromatin of rats subjected to restraint stress, revealed recruitment of TORC2 and phospho-CREB by the CRH promoter at 30 min, but 3h after stress only phospho-CREB remained associated with the CRH promoter [69, 71].

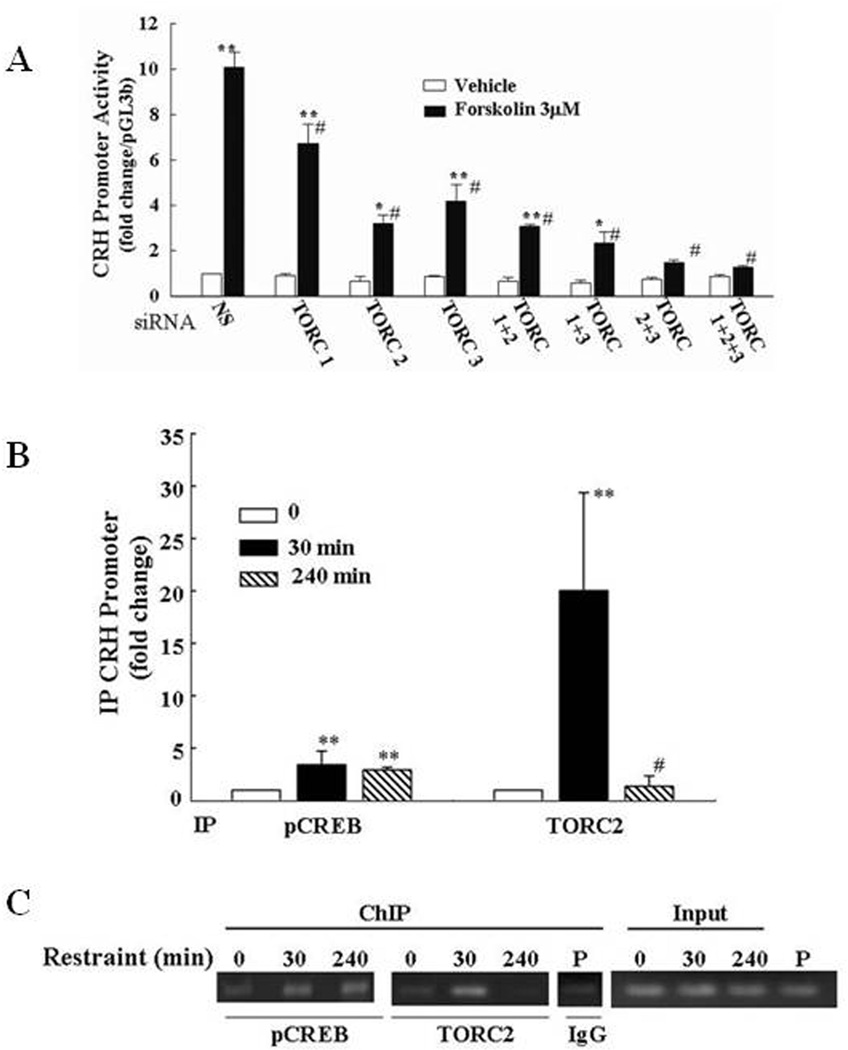

The use of overexpression and knock out of endogenous TORC has provided compelling evidence for the functional involvement of TORC on CRH transcription. In these experiments, transfection of TORC, especially TORC 2 in 4B cells, potentiated the effect of forskolin on CRH promoter activity. On the other hand, knockdown of endogenous expression of each TORC isoform using silencing RNA (siRNA) inhibited the stimulatory effect of forskolin on CRH transcription in a reporter gene assay, as well as in primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons. Combined knockdown of TORC2 and TORC3 completely blocked stimulated CRH promoter activity without reducing the increase in phospho-CREB levels (Fig 9).

Figure 9. Evidence for the involvement of TORC on CRH transcription.

(A) Silencing (si)RNA blockade of specific TORC subtypes reduces forkolin-stimulated CRH transcription in primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons. Neuronal cultures were transfected with a non specific (NS), or TORC1, TORC2 or TORC 3 siRNA, and 24h later incubated for 45min with forskolin (Fsk) or vehicle (0.01% DMSO) before preparation of total RNA for determination of TORC mRNA and CRH hnRNA by qRT-PCR. Bars are the mean and SE of data obtained in 4 experiments, expressed as fold-change from vehicle in cells transfected with NS. **, p<0.001 siRNA vs. NS (TORC mRNA), or forskolin vs. respective vehicle; *, or p<0.03 forskolin vs. respective vehicle; #, p< 0.001 forskolin siRNA vs.forskolin non-specific oligonucleotide. (B) Restraint stress induces recruitment of phospho-CREB and TORC2 by the CRH promoter in the hypothamic PVN region. ChIP assays using phospho-CREB and TORC 2 antibodies and cross-linked DNA from microdissected hypothalamic PVN region of control rats and rats subjected to restraint stress for 30min or 3h after 1h restraint (240 min) (A). Amounts of CRH promoter DNA in the immunoprecipitant were measured by qRT-PCR. Bars represent the mean and SE of the results obtained in 4 experiments using pooled tissue from 2 or 3 rats per experimental point. (C) Representative gel showing the results obtained in pools of 3 hypothalamic sections per group in a representative experiment (B). **, p< 0.01 higher than basal; **, p<0.02 higher than basal; #, p<0.02 lower than 30 min.

The mechanisms by which cyclic AMP activates TORC and induces its nuclear translocation and interaction with the CRH promoter are currently under investigation. These studies are revealing novel information indicating that salt inducible kinase (SIK) mediates the phosphorylation and cytoplasmic sequestration of TORC 2 in hypothalamic neurons (Liu and Aguilera, unpublished).

Overall, the long time accepted concept that the cyclic AMP/PKA/phospho-CREB pathway and the CRE in the CRH promoter are critical for activation of CRH transcription is still valid. However, it has become clear that binding of CREB alone to the CRH promoter is not sufficient to drive transcription but that it requires nuclear translocation and interaction with the co-activator TORC. While a number of signaling systems can lead to CREB phosphorylation it appears that cyclic AMP is essential for SIK inhibition and the nuclear translocation of TORC. A diagram depicting the proposed mechanisms regulating TORC activity and induction of CRH transcription is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Diagram representing the signaling pathways regulating TORC translocation to the nucleus and activation of CRH transcription.

In basal conditions TORC is in the cytoplasm, in an inactive state phosphorylated at Ser 171 and bound to the scaffolding protein 14-3-3. Based on the described effect of the phorbol ester, PMA, on TORC phosphorylation, and known ability of salt inducible kinase (SIK) to phosphorylate TORC, it is likely that protein kinase C (PKC) activates SIK, which in turn maintains TORC phosphorylated in the cytoplasm. Stimulation of adenylate cyclase (AC) by forskolin or a G-protein coupled receptor (not shown) leads to cyclic AMP production and stimulation of protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates SIK at Ser 577 and inactivates it, blocking TORC phosphorylation. In addition, increase in intracellular calcium stimulates the phosphatase, calcineurin (PPP3), which has been shown to dephosphorylate TORC. Upon dephosphorylation, TORC dissociates from 14-3-3 nad translocates to the nucleus (indicated by the green dotted lines) where it interacts with CREB at the cyclic AMP response element in the CRH promoter and facilitates the recruitment the transcription initiation complex including CREB binding protein (CBP)/p300, TATA binding protein (TBP), TBP associated factors (TAFII) and RNA polymerase II (Pol II).

6.3 Negative regulation of CRH transcription

Since excessive production of CRH can predispose to disease not only by over stimulating HPA axis activity but also because of the direct effects of the peptide in the brain, shutting down CRH transcription is essential for homeostasis and health. In addition to changes in stimulatory and inhibitory neurocircuitry activity and glucocorticoid feedback, it is likely that intracellular feedback mechanisms contribute to limiting transcription in the CRH neuron.

6.3.1 Effects of glucocorticoids on CRH transcription

While it is clear that in vivo glucocorticoids inhibit CRH transcription, the exact molecular mechanism of the inhibitory effect is not fully understood. Although several investigators have reported direct effects of glucocorticoids on CRH promoter activity, the majority of the studies have been performed in transfected cell lines not representative of the hypothalamic CRH neuron. There is no classical glucocorticoid response element (GRE) in the CRH promoter but there is evidence from reporter gene assays that glucocorticoids can regulate CRH gene expression through protein–protein interaction or by binding directly to response elements [94]. Glucocorticoids can have stimulatory or inhibitory effects on CRH promoter activity depending on the cell type [94]. Experiments using reporter gene assays have shown negative glucocorticoid regulation of cyclic AMP-stimulated CRH promoter activity but not on basal activity, suggesting that the glucocorticoid response depends on interaction with a CRE associated transcriptional complex. Dexamethasone-dependent repression of cAMP-stimulated CRH promoter activity was localized to the −278/−249 region of the human promoter, where specific, high-affinity binding of glucocorticoid receptor was found. Deletion of this region reduced glucocorticoid-dependent repression of CRH promoter activity [80].

It is noteworthy that in vivo experiments in adrenalectomized rats have shown that administration of high doses of corticosterone, increasing plasma levels by about 100-fold those observed during stress, was unable to significantly affect the magnitude or duration of the increase in CRH primary transcript (hnRNA) in response to a mild stress [77]. This observation is in contrast to the marked blunting effect of glucocorticoids on stress-stimulated CRH transcription in intact rats. This suggests the interaction of transcription factors induced by stress in adrenalectomized (but not in intact rats) with the ability of the glucocorticoid receptor to repress transcription. However, whether this interaction occurs at the level of the CRH promoter or other sites remains to be elucidated. Although there is evidence suggesting that glucocorticoids can inhibit CRH transcription [39, 80, 94], the lack of a cell line representative of parvocellular CRH neurons has made it difficult to elucidate the relative importance of direct transcriptional repression and indirect actions on afferent pathways.

6.3.2 Intracellular feedback mechanisms

Experiments in adrenalectomized rats replaced with constant low levels of corticosterone showed that CRH hnRNA responses to prolonged restraint are transient in spite of the lack of glucocorticoid responses to stress [116]. This provides clear evidence that the glucocorticoid surge is not essential for limiting transcription and that transcriptional activation can be transient in spite of the lack of a glucocorticoid surge.

As indicated above, transcriptional regulation of the CRH gene involves cAMP/CREB-dependent mechanisms and a functional CRE in the CRH promoter [1, 73, 113]. Although it has been shown that CREB phosphorylation coincides with elevations in CRH hnRNA in the PVN during ether exposure [57, 116], a lack of correlation between the decline in phospho-CREB and reduced CRH hnRNA levels suggests that the termination of CRH transcription involves not only decreases in phospho-CREB levels but also a transcriptional repressor. Studies in rats have shown that the repressor, Inducible Cyclic AMP Early Repressor (ICER) is indeed involved in the regulation of CRH transcription [70, 72, 116]. ICER, a product of activation of the second promoter of the CREM gene, had been previously reported to repress cAMP-induced transcription in other neuroendocrine tissues, such as the pineal, pituitary, Sertoli cells and adrenal gland [34, 59, 61, 70, 72, 90, 116].

There is experimental evidence that stress induces ICER in the hypothalamic PVN and that ICER interacts with the CRH CRE in the PVN [116]. While the appearance of phospho-CREB is rapid, reaching maximal levels about in 30 min depending on the stress paradigm, ICER mRNA and protein become evident by 1 h and reaches maximum by 3h [116]. Double staining in situ hybridization studies have shown that ICER induced during stress co-localizes with CRH in parvocellular PVN neurons [116]. In the same study, gel shift assays and chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that ICER is recruited by the CRH promoter in correspondence with a decrease in Pol II binding to the CRH promoter. Further evidence for the involvement of ICER in limiting CRH transcription has been provided by experiments using CREM siRNA to prevent the formation of endogenous ICER [72]. In these experiments, co-transfection of 4B cells with CREM siRNA and a CRH promoter-driven luciferase reporter gene markedly reduced the induction of ICER by forskolin and potentiated the stimulatory effect of forskolin on CRH promoter activity, compared with cells co-transfected with a nonspecific oligonucleotide. Moreover, in primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons stimulation of CRH transcription (measured as changes in CRH hnRNA) is transient in spite of sustained stimulation with forskolin (Figure 11-A). Consistent with the observations in vivo, the decline in CRH hnRNA by 3 h is associated with increases in ICER protein (Figure 11-B). Transfection of CREM siRNA in these primary cultures partially reversed the declining phase of CRH hnRNA production at 3 h (Figure 11-C and D). These findings provide evidence that endogenous ICER formation is required for termination of CRH transcription and support the hypothesis that ICER is part of an intracellular feedback mechanism which limits CRH transcription during stress.

Figure 11.

Time course of the effects of forskolin on ICER I and II production (A) and CRH transcription (B) Cell were incubated for the time periods indicated before processing for western blot analysis or CRH hnRNA determination by intronic real time PCR (B). Data points are the mean and SE of the values in 3 experiments. *, p<0.001 vs time 0; #, p<0.001 vs 1h. Blockade of endogenous ICER in primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons using CREM siRNA reduced forskolin-induced ICER I and II protein levels (C) and CRH hnRNA levels (D). Cells were incubated for 3h with forskolin (Fsk) before preparation of protein extracts for western blot. Bars are the mean and SE of ICER, expressed as percent of forskolin-stimulated values in cells transfected with the non-specific oligonucleotide *, p<0.05. CRH hnRNA levels are expressed as percent of stimulation at 1h. As shown in D, CREM siRNA significantly reduced the decline in CRH hnRNA observed after 3h incubation with forskolin. *, p<0.05 CREM siRNA compared with non-specific oligonucleotide (NS).

An additional mechanism which could be involved in limiting the activation of CRH transcription during stress is regulation of the activity of the CREB co-activator, TORC. As indicated above, activation and inactivation of TORC appears to be the determining factor for activation of CRH transcription. Since TORC inactivation depends on the Ser/Thr kinase, SIK, it is likely that activation of SIK activity may act as a break mechanism by phosphorylating and inactivating TORC. This hypothesis is currently under investigation.

7. Concluding remarks

Corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) produced by parvocellular neurons of the hypothalamic PVN (and other brain areas) is the major regulator of hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis activity, as well as behavioral and autonomic responses to stress. In resting conditions the hypothalamic CRH neuron displays a diurnal (circadian) rhythm. Activity markedly increases during stress, leading to release and de novo synthesis of CRH. Activation of the CRH neuron depends on complex afferent neural pathways to the PVN originating in the brain stem and limbic system, the recruitment of which depends on the nature, intensity and duration of the stress. Inputs from these neural pathways trigger signaling transduction mechanisms in the CRH neuron, which mediate rapid secretion of CRH followed by increases in CRH gene transcription, translation and processing of newly synthesized peptide. Transcriptional activation of the CRH gene is mediated by cyclic AMP/protein kinase A/phospho-CREB dependent pathways. This includes interaction of phospho-CREB with the CRE in the proximal CRH promoter, but only recently it has become evident that initiation of CRH transcription requires cyclic AMP-dependent translocation of the CREB co-activator, Transducer of regulated CREB activity, TORC. While activation of the CRH neuron is required to restore mRNA and peptide levels, termination of the response is essential to prevent pathology associated with chronic elevations of CRH and HPA axis activity. Elevated plasma levels of adrenal glucocorticoids, as a consequence of HPA axis activation, plays an important role in limiting the magnitude and duration of the activation of CRH neurons during stress. In addition, delayed induction of the repressor, inducible cyclic AMP early repressor (ICER) contributes to limiting the duration of the transcriptional response of the CRH gene. An interesting possibility currently under investigation is that rapid sequential activation and inactivation of salt-inducible kinase (SIK) plays a primary role on CRH transcription by regulating the activity of the CREB co-activator, TORC.

Although considerable progress has been made during the last few years in understanding the complex neural pathways and molecular mechanisms controlling the CRH neuron, future work is clearly needed to elucidate important questions such as the mode of interaction between the glucocorticoid receptor, AP1 factors and other immediate early genes with the CRH promoter, as well as the mechanism of differential regulation of CRH expressed in the hypothalamus and other areas of the limbic system. Since TORC is emerging as the determinant factor for regulation of CRH transcription, elucidation of the mechanism by which cyclic AMP and other signaling pathways regulate the kinases and phosphatases responsible for TORC activation/inactivation will open new perspectives to understand the transient patterns of activation of the CRH neuron as well as the mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of stress related disorders.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

References

- 1.Adler GK, Smas CM, Fiandaca M, Frim DM, Majzoub JA. Regulated expression of the human corticotropin releasing hormone gene by cyclic AMP. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1990;70:165–174. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(90)90156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilera G, Young WS, Kiss A, Bathia A. Direct regulation of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing-hormone neurons by angiotensin II. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;61:437–444. doi: 10.1159/000126866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aguilera G. Regulation of Pituitary ACTH Secretion during Chronic Stress. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1994;15:321–350. doi: 10.1006/frne.1994.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aguilera G. Corticotropin Releasing Hormone, Receptor Regulation and the Stress Response. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1998;9:329–336. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(98)00079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguilera G, Kiss A, Liu Y, Kamitakahara A. Negative regulation of corticotropin releasing factor expression and limitation of stress response. Stress. 2007;10:153–161. doi: 10.1080/10253890701391192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguilera G, Subburaju S, Young S, Chen J. The parvocellular vasopressinergic system and responsiveness of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis during chronic stress. Prog Brain Res. 2008;170:29–39. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00403-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander SL, Irvine CH, Donald RA. Short-term secretion patterns of corticotropin-releasing hormone, arginine vasopressin and ACTH as shown by intensive sampling of pituitary venous blood from horses. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;60:225–236. doi: 10.1159/000126755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antoni FA. Vasopressinergic control of pituitary adrenocorticotropin secretion comes of age. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1993;14:76–122. doi: 10.1006/frne.1993.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnett MG, Kolber BJ, Boyle MP, Muglia LJ. Behavioral insights from mouse models of forebrain- and amygdala-specific glucocorticoid receptor genetic disruption. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;336:2–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bali B, Kovacs KJ. GABAergic control of neuropeptide gene expression in parvocellular neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Eur J Neuroscie. 2003;18:1518–1526. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baram TZ, Lerner S. Ontogeny of corticotropin releasing hormone gene expression in rat hypothalamus--comparison with somatostatin. Int J Develop Neuroscie. 1991;9:473–478. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(91)90033-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartanusz V, Aubry JM, Jezova D, Baffi J, Kiss JZ. Up-regulation of vasopressin mRNA in paraventricular hypophysiotrophic neurons after acute immobilization stress. Neuroendocrinol. 1993;58:625–629. doi: 10.1159/000126602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatnagar S, Dallman M. Neuroanatomical basis for facilitation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to a novel stressor after chronic stress. Neuroscience. 1998;84:1025–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatnagar S, Huber R, Nowak N, Trotter P. Lesions of the Posterior Paraventricular Thalamus Block Habituation of Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Responses to Repeated Restraint. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14:403–410. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1331.2002.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown MR, Fisher LA. Corticotropin-releasing factor: effects on the autonomic nervous system and visceral systems. Fed Proc. 1985;44:243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bugnon C, Fellmann D, Gouget A, Cardot J. Immunocytochemical study of the ontogenesis of the CRF-containing neuroglandular system in the rat. Comptes Rendue French Acad Scie. 1982;294:599–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter DA, Lightman SL. Diurnal pattern of stress-evoked neurohypophyseal hormone secretion: Sexual dimorphism in rats. Neuroscie Lett. 1986;71:252–255. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90568-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J J, Young S, Subburaju S, Shepard J, Kiss A, Atkinson H, Wood S, Lightman SL, Serradeil-Le Gal C, Aguilera G. Vasopressin does not mediate hypersensitivity of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis during chronic stress. Ann NY Acad Scie. 2008;1148:349–359. doi: 10.1196/annals.1410.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Rex CS, Rice C, Dube CM, Gall CM, Lynch G, Baram TZ. Correlated memory defects and hippocampal dendritic spine loss after acute stress involve corticotropin-releasing hormone signaling. Proc Natl Acad Scie USA. 2010;107:13123–13128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003825107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung S, Son GH, Kim K. Circadian rhythm of adrenal glucocorticoid: Its regulation and clinical implications. Bioch Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conkright MD, Canettieri G, Screaton R, Guzman E, Miraglia L, Hogenesch JB, Montminy M. TORCs: Transducers of Regulated CREB Activity. Mol Cell. 2003;12:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conti AC, Maas J, Muglia LM, Dave BA, Vogt SK, Tran TT, Rayhel EJ, Muglia LJ. Distinct regional and subcellular localization of adenylyl cyclases type 1 and 8 in mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2007;146:713–729. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cullinan WE, Ziegler D, Herman JP. Functional role of local GABAergic influences on the HPA axis. Brain Struct Function. 2008;213:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cullinan WE. GABAA receptor subunit expression within hypophysiotropic CRH neurons: A dual hybridization histochemical study. J Comp Neurol. 2000;419:344–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000410)419:3<344::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daikoku S, Okamura Y, Kawano H, Tsuruo Y, Maegawa M, Shibasaki T. Immunohistochemical study on the development of CRF-containing neurons in the hypothalamus of the rat. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;238:539–544. doi: 10.1007/BF00219870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dallman MF, Akana SF, Levin N, Walker CD, Bradbury MJ, Suemaru S, Scribner KS. Corticosteroids and the Control of Function in the Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis. Ann NY Acad Scie. 1994;746:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb39206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Day H, Campeau S, Watson SJ, Akil H. Expression of alpha(1b) adrenoceptor mRNA in corticotropin-releasing hormone-containing cells of the rat hypothalamus and its regulation by corticosterone. J Neurosci. 1999;19::10098–10106. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-10098.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Goeij DC, Kvetnansky R, Whitnall MH, Jezova D, Berkenbosch F, Tilders FJ. Repeated stress-induced activation of corticotropin-releasing factor neurons enhances vasopressin stores and colocalization with corticotropin-releasing factor in the median eminence of rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1991;53:150–159. doi: 10.1159/000125712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di S, Malcher-Lopes R, Halmos KC, Tasker JG. Nongenomic Glucocorticoid Inhibition via Endocannabinoid Release in the Hypothalamus: A Fast Feedback Mechanism. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4850–4857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04850.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diorio D, Viau V, Meaney MJ. The role of the medial prefrontal cortex (cingulate gyrus) in the regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. J Neuroscie. 1993;13:3839–3847. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03839.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evanson NK, Herman JP, Sakai RR, Krause EG. Nongenomic actions of adrenal steroids in the central nervous system. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:846–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fenoglio KA, Brunson KL, Vishai-Eliner S, Chen Y, Baram TZ. Region-Specific Onset of Handling-Induced Changes in Corticotropin-Releasing Factor and Glucocorticoid Receptor Expression. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2702–2706. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feuvrier E, Aubert M, Mausset AL, Alonso G, Gaillet S, Malaval F, Szafarczyk A. Glucocorticoids Provoke a Shift from alpha to beta-adrenoreceptor activities in cultured hypothalamic slices leading to opposite noradrenaline effect on corticotropin-releasing hormone release. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1199–1209. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70031199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foulkes NS, Borrelli E, Sassone-Corsi P. CREM gene: use of alternative DNA-binding domains generates multiple antagonists of cAMP-induced transcription. Cell. 1991;64:739–749. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90503-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ginsberg AB, Campeau S, Day HE, Spencer RL. Acute glucocorticoid pretreatment suppresses stress-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hormone secretion and expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone hnRNA but does not affect c-fos mRNA or Fos protein expression in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:1075–1083. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grinevich V, Fournier A, Pelletier G. Effects of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) on corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) gene expression in the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Brain Res. 1997;773:190–196. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grino M, Young WS, Burgunder JM. Ontogeny of expression of the corticotropin-releasing factor gene in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and of the proopiomelanocortin gene in rat pituitary. Endocrinology. 1989;124:60–68. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-1-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guardiola-Diaz HM, Boswell C, Seasholtz AF. The cAMP-responsive element in the corticotropin-releasing hormone gene mediates transcriptional regulation by depolarization. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14784–14791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guardiola-Diaz HM, Kolinske JS, Gates LH, Seasholtz AF. Negative glucorticoid regulation of cyclic adenosine 3', 5'-monophosphate-stimulated corticotropin-releasing hormone-reporter expression in AtT-20 cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:317–329. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.3.8833660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harbuz MS, Lightman SL. Glucocorticoid inhibition of stress-induced changes in hypothalamic corticotrophin-releasing factor messenger RNA and proenkephalin A messenger RNA. Neuropeptides. 1989;14:17–20. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(89)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He X, Treacy MN, Simmons DM, Ingraham HA, Swanson LW, Rosenfeld MG. Expression of a large family of POU-domain regulatory genes in mammalian brain development. Nature. 1989;340:35–42. doi: 10.1038/340035a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herman JP, Prewitt CM, Cullinan WE. Neuronal circuit regulation of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical stress axis. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1996;10:371–394. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v10.i3-4.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herman JP, Schafer MK, Thompson RC, Watson SJ. Rapid regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone gene transcription in vivo. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:1061–1069. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.7.1324419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herman JP, Schäfer MK, Watson SJ, Sherman TG. In situ hybridization analysis of arginine vasopressin gene transcription using intron-specific probes. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:1447–1456. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-10-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herman JP, Figueiredo H, Mueller NK, Ulrich-Lai Y, Ostrander MM, Choi DC, Cullinan WE. Central mechanisms of stress integration: hierarchical circuitry controlling hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical responsiveness. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2003;24:151–180. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herman JP, Tasker JG, Ziegler DR, Cullinan WE. Local circuit regulation of paraventricular nucleus stress integration: Glutamate-GABA connections. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:457–468. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00681-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iourgenko V, Zhang W, Mickanin C, Daly I, Jiang C, Hexham JM, Orth AP, Miraglia L, Meltzer J, Garza D, Chirn GW, McWhinnie E, Cohen D, Skelton J, Terry R, Yu Y, Bodian D, Buxton FP, Zhu J, Song C, Labow MA. Identification of a family of cAMP response element-binding protein coactivators by genome-scale functional analysis in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Scie USA. 2003;100:12147–12152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932773100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Itoi K, Horiba N, Tozawa F, Sakai Y, Sakai K, Abe K, Demura H, Suda T. Major role of 3',5'-cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase A pathway in corticotropin-releasing factor gene expression in the rat hypothalamus in vivo. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2389–2396. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.6.8641191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jezova D, Ochedalski T, Glickman M, Kiss A, Aguilera G. Central corticotropin-releasing hormone receptors modulate hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical and sympathoadrenal activity during stress. Neuroscience. 1999;94:797–802. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kageyama K, Hanada K, Iwasaki Y, Sakihara S, Nigawara T, Kasckow J, Suda T. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide stimulates corticotropin-releasing factor, vasopressin and interleukin-6 gene transcription in hypothalamic 4B cells. J Endocrinol. 2007;195:199–211. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]