Abstract

The epithelial cells of the mammary gland develop primarily after birth and undergo surges of hormonally regulated proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis during both puberty and pregnancy. Thus, the mammary gland is a useful model to study fundamental processes of development and adult tissue homeostasis, such as stem and progenitor cell regulation, cell fate commitment, and differentiation. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are emerging as prominent regulators of these essential processes, as their extraordinary versatility allows them to modulate gene expression via diverse mechanisms at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Not surprisingly, lncRNAs are also aberrantly expressed in cancer and promote tumorigenesis by disrupting vital cellular functions, such as cell cycle, survival, and migration. In this review, we first broadly summarize the functions of lncRNAs in mammalian development and cancer. Then we focus on what is currently known about the role of lncRNAs in mammary gland development and breast cancer.

Keywords: lncRNAs, Mammary gland, Development, Differentiation, Breast cancer

1. Introduction

1.1. LncRNAs and development

A fundamental goal in developmental biology is to understand how stem and progenitor cells differentiate and perform specialized functions in each tissue type of a particular organism. Cells proceed toward differentiation through highly coordinated, stepwise changes in gene expression that are largely regulated by cell-type dependent transcription factor networks, resulting in a mixed population of stem, progenitor, and differentiated cell types. The precise regulation of this cellular hierarchy is essential for creating and maintaining the structure and function of an organ. Additionally, the preservation of each cell type in a given tissue requires maintenance of their unique patterns of gene expression, which is thought to be regulated predominantly by epigenetic mechanisms. In the past decade, long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as significant regulators of tissue- and cell-specific gene expression by diverse mechanisms, many of which result in targeted epigenetic modifications. Therefore, it is not surprising that there is growing evidence of an instructional role for lncRNAs in mediating key processes in cellular differentiation and development (Hu et al., 2011).

Relatively few lncRNAs have identified functions. However, a large portion of these regulate developmental processes in embryonic and adult mammalian tissue. Some of the earliest characterized lncRNAs regulate distinct epigenetic processes that are critical for embryonic development, such as the regulation of genomic imprinting by H19 (Bartolomei and Ferguson-Smith, 2011) and X-inactivation by Xist (Jeon et al., 2012). Imprinting and X-inactivation are both mediated by multiple lncRNA-chromatin modifying complexes that target and silence genes in cis (Lee and Bartolomei, 2013). In addition, large-scale analyses using mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) have identified hundreds of lncRNAs, some of which are differentially expressed in various stages of mESC differentiation (Dinger et al., 2008; Guttman et al., 2009). Loss-of-function studies of dozens of mESC lncRNAs show that they act to repress lineage commitment programs to maintain the mESC pluripotent state (Guttman et al., 2011). Other lncRNAs, such as Mira, may be induced by, and necessary for, mESC differentiation (Bertani et al., 2011). Taken together, these data support a central role for lncRNAs in regulating key processes during embryogenesis, including genomic imprinting and dosage compensation, as well as mESC pluripotency and differentiation.

In the adult, lncRNAs often show precise spatiotemporal expression patterns (Cabili et al., 2011; Derrien et al., 2012; Djebali et al., 2012; Ravasi et al., 2006), reflecting their potential role in regulating lineage commitment and differentiation. Consistent with this proposal, several lncRNAs have been shown to regulate cell fate decisions across a broad range of tissues. For example, global analyses have identified a large number of lncRNAs that show discrete patterns of expression in the central nervous system (Mercer et al., 2008; Ng et al., 2012; Ponjavic et al., 2009; Qureshi et al., 2010). Further studies have shown that several lncRNAs are required for proper neural differentiation and development, such as Evf2 (Bond et al., 2009), Six3os, and Dlx1as (Ramos et al., 2013). In addition, the expression of several lncRNAs is induced during, and necessary for, the differentiation of distinct hematopoietic lineages, including EGO (Wagner et al., 2007), HOTAIRM1 (Zhang et al., 2009), and LincRNA-EPS (Hu, Yuan, 2011). Another lncRNA called Linc-MD1 promotes muscle differentiation by binding and sequestering miRNAs that repress myogenic genes (Cesana et al., 2011). In the epidermis, ANCR represses terminal differentiation by an unknown mechanism (Kretz et al., 2012), whereas TINCR promotes terminal differentiation by binding and stabilizing differentiation mRNAs (Kretz et al., 2013). LncRNAs have also been shown to regulate heart development, likely via epigenetic mechanisms. The lncRNA Bvht interacts with the PRC2 complex and is required for cardiomyocyte differentiation in vitro (Klattenhoff et al., 2013), whereas the lncRNA Fendrr binds to both the PRC2 and MLL complexes, and it is essential for proper mouse heart development in vivo (Grote et al., 2013). Interestingly, recent evidence shows that several imprinted genes, including the lncRNA H19, are not only expressed embryonically, but are also enriched specifically in adult somatic stem cells where they may play an additional role in regulating the balance between stem cell self-renewal and differentiation in several adult tissues (Berg et al., 2011; Ferron et al., 2011; Venkatraman et al., 2013; Zacharek et al., 2011).

1.2. LncRNAs and cancer

Since lncRNAs regulate critical pathways in tissue development and maintenance, it might be assumed that the misregulation of lncRNAs could disrupt these delicate processes and lead to tumorigenesis. Recent transcriptional profiling of multiple human tissues, including both normal and tumor samples, have indeed begun to provide global evidence for the misexpression of lncRNAs in cancer (Brunner et al., 2012; Gibb et al., 2011b). These studies have validated the tissue-specific expression of lncRNAs in normal tissues, and have identified large sets of lncRNAs that are aberrantly expressed in either a specific cancer or multiple types of cancer. A recent large-scale study went a step further by integrating microarray data of lncRNA expression from 1,300 tumors, spanning four types of cancer, with clinical outcome and somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) data, and identified 80–300 potential lncRNA drivers of cancer progression in each of the four cancer types (Du et al., 2013). These global analyses provide valuable resources for the identification of novel cancer biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Cancer is thought to arise and progress due to genetic alterations that disrupt processes required for maintaining normal cellular homeostasis, such as cell cycle, DNA damage response, survival, and migration (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). Misregulated lncRNAs that affect each of these processes have been identified in cancer (Gibb et al., 2011a; Martin and Chang, 2012; Prensner and Chinnaiyan, 2011; Spizzo et al., 2012). For example, the lncRNAs PRNCR1 and PCGEM1 are highly expressed in aggressive prostate cancer where they bind to the androgen receptor (AR) and enhance AR-mediated gene activation programs, leading to increased proliferation (Chung et al., 2011; Petrovics et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2013). Another lncRNA, called PANDA, is induced in response to DNA damage in a p53-dependent manner (Hung et al., 2011). PANDA promotes cell survival by binding the transcription factor NY-FA and inhibiting its activation of apoptotic genes. LncRNAs can also regulate cell migration, as evidenced by the lncRNA MALAT1, which is upregulated in metastatic lung cancer (Ji et al., 2003). Knockdown of MALAT1 reduces lung cancer cell migration and results in the misregulation of genes associated with cell motility in vitro. Depletion of MALAT1 also reduces metastasis of lung cancer cells in a pulmonary metastatic model in vivo (Gutschner et al., 2013b). As the functions of individual lncRNAs in cancer are beginning to be elucidated, they are being categorized and referred to as either tumor suppressor or oncogenic lncRNAs, in the same way as traditional protein-coding cancer genes (Huarte et al., 2010). They are also being discussed in relation to the well-known Hallmarks of Cancer progression, as described by Hanahan and Weinberg, thus expanding these concepts of tumorigenesis to include the noncoding genome (Gutschner and Diederichs, 2012; Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011).

In this review, we will focus on the role of lncRNAs in regulating development and differentiation of mammary epithelial cells in the normal mammary gland. Additionally, we will discuss the misregulation of lncRNAs implicated in mammary tumorigenesis, as well as how these misregulated lncRNAs might disrupt normal mammary epithelial cell development (Table 1).

Table 1.

LncRNAs associated with mammary development and breast cancer.

| LncRNA | Expression | Function | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mammary development | |||

| mPINC | Highly expressed in alveolar cells of pregnant and involuting gland | Inhibits lactogenic differentiation, alternative splice forms regulate cell cycle and survival | Interacts with PRC2 |

| Zfas1 | Highly expressed in alveolar and ductal cells of pregnant and involuting gland | Inhibits proliferation and lactogenic differentiation | Unknown |

| Breast cancer | |||

| BC200 | Increased in invasive breast cancer and HG-DCIS | Oncogenic | Translational repressiona |

| GAS5 | Decreased in breast tumors and breast cancer cell lines | Tumor suppressive-induces growth arrest and apoptosis | Binds and inhibits GR from activating target genesa |

| HOTAIR | Increased in metastatic breast tumors, strong predictor of metastasis and death | Oncogenic-promotes invasion and metastasis | Silences genes in trans epigenetically |

| H19 | Increased in stromal cells of breast tumors | Oncogenic-promotes proliferation and tumor growth Tumor suppressive-restricts growtha | Unknown |

| LncRNA-JADE | Increased in breast tumors | Oncogenic-promotes proliferation and survival | Binds BRCA1 and enhances transcription of Jade1 in DDR |

| LSINCT5 | Increased in breast tumors and breast cancer cell lines | Oncogenic-promotes proliferation | Unknown |

| MALAT1 | Increased in breast tumors, mutations in MALAT1 associated with Luminal B subtype and poor clinical outcome | Oncogenic-promotes metastasisa | RNA splicing, regulation of gene expressiona |

| MEG3 | Expressed in mammary gland, not detected in breast cancer cell lines | Tumor suppressive-inhibits growth, induces apoptosisa | Unknown |

| PTENP1 | Focally deleted in breast cancer, undergoes somatic hypermethylation in breast cancer cell lines | Tumor suppressive-represses proliferationa | Binds and inhibits miRNAs from targeting and repressing PTEN |

| SRA | Increased in breast tumors, associated with PR+ breast tumors | Oncogenic-promotes proliferation, metastasis Tumor suppressive-induces apoptosis | Co-activator of hormone receptors, scaffold for many transcription factorsa |

| treRNA | Increased in paired breast cancer primary and lymph-node metastasis samples | Oncogenic-promotes EMT, invasion and metastasis | Enhances transcription of EMT regulators, represses translation of epithelial markers |

| UCA1 | Increased in breast tumors, negatively correlates with p27 protein levels | Oncogenic-promotes proliferation | Binds hnRNP I, thereby preventing binding and translation of p27 |

| ZFAS1 | Decreased in invasive ductal carcinoma | Tumor suppressive-inhibits proliferation | Unknown |

Data not shown in breast cancer cells.

2. LncRNAs: form and mechanism

LncRNAs are often capped, spliced, and polyadenylated, similar to their protein-coding counterparts. LncRNAs were initially defined as RNA transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides that lack protein-coding potential. However, this definition has since become blurred by accumulating evidence for multifunctional RNA molecules, such as lncRNAs that also encode proteins, and mRNAs that also function as lncRNAs (Candeias et al., 2008; Dinger et al., 2011; Poliseno et al., 2010). In addition, the length ascribed in the previous definition is somewhat arbitrary and limiting, as some RNA molecules that do not meet this requirement still function as lncRNAs, such as the lncRNA BC200, which will be discussed later in this review. Although the definition of lncRNAs will likely continue to evolve, the current definition is any regulatory RNA transcript that is not a small ncRNA, such as microRNAs (miRNAs), PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), or small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) (Spizzo et al., 2012). However, to further clarify, some lncRNAs also contain miRNAs (Cai and Cullen, 2007) and snoRNAs (Mourtada-Maarabouni et al., 2009) embedded within them. Therefore, a further amendment to the definition should state that classifying an RNA molecule as an lncRNA does not preclude it from possessing other coding and noncoding functions.

Thousands of lncRNAs are transcribed from the mammalian genome, and their predominant role seems to be the regulation of gene expression by a diverse spectrum of mechanisms (Rinn and Chang, 2012). Some lncRNAs are transcribed from enhancer regions (eRNAs) and are required to increase the expression of neighboring genes in cis (Orom et al., 2010), whereas others bind and sequester transcription factors, thus inhibiting transcription factor activity (Hung et al., 2011; Kino et al., 2010). LncRNAs can also bind to transcription factors and enhance their transcriptional activity, thus acting as co-activators (Caretti et al., 2006; Feng et al., 2006). Finally, one of the most recurrent mechanisms reported is the ability of lncRNAs to recruit chromatin-modifying complexes to target loci, thereby epigenetically activating or repressing associated genes (Lee, 2012; Mercer and Mattick, 2013). Thousands of lncRNAs have been shown to interact with the repressive chromatin-modifying complex PRC2 (Zhao et al., 2010), and many lncRNAs have been found to interact with other chromatin-modifying complexes, such as LSD1/REST/CoREST (Khalil et al., 2009; Tsai et al., 2010), PRC1 (Yap et al., 2010) and MLL1 (Bertani et al., 2011; Dinger et al., 2008; Grote et al., 2013), suggesting a substantial fraction of lncRNAs act as epigenetic regulators. The majority of lncRNAs discussed in the following sections utilize at least one of the above described mechanisms to function in mammary development and tumorigenesis.

3. Development of the mammary gland

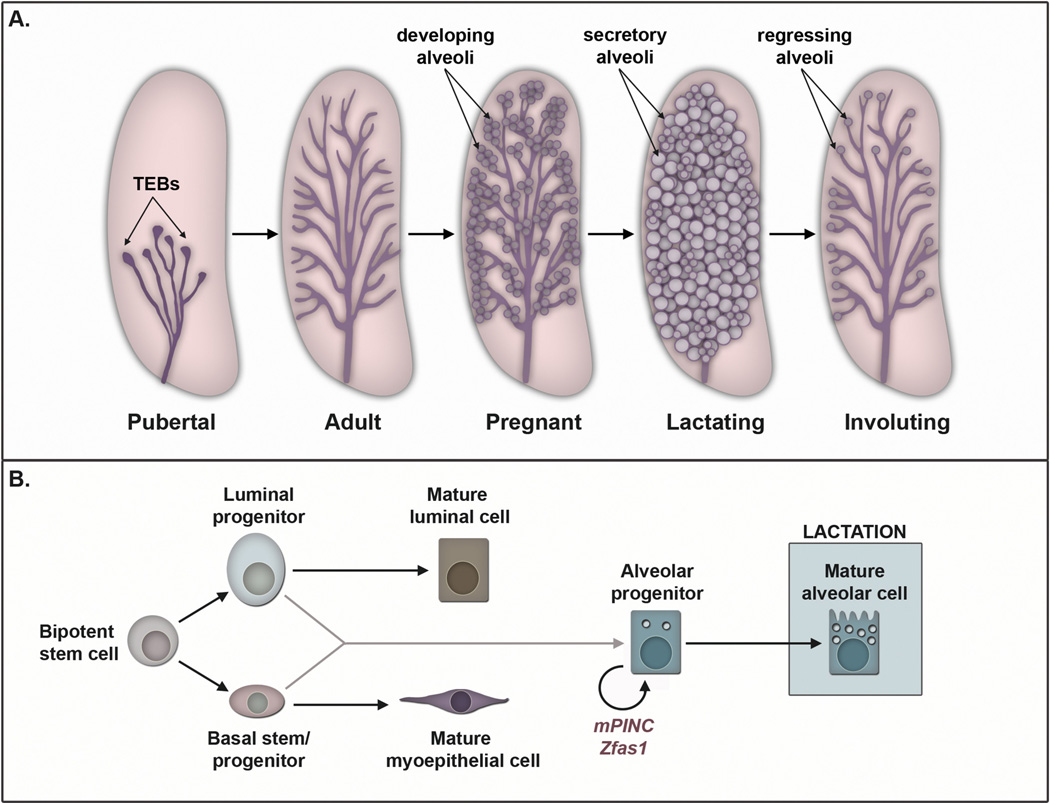

The mammary gland is a unique organ from a developmental perspective, as the majority of its growth and differentiation occurs after birth (Fig. 1A) (Cowin and Wysolmerski, 2010; Gjorevski and Nelson, 2011; Watson and Khaled, 2008). At birth, the mammary fat pad contains a simple epithelial ductal structure that quiescently lies beneath the nipple until puberty. During puberty, ovarian and pituitary hormones, including estrogen, progesterone, and growth hormone, stimulate proliferation of the mammary epithelial cells to generate terminal end bud (TEB) structures at the leading tips of the ducts (Brisken and O’Malley, 2010).TEBs are dynamic structures made up of proliferative, as well as apoptotic, epithelial cells, both of which are necessary to allow ductal elongation and lumen formation. TEBs drive extension and bifurcation of the ducts toward the ends of the fat pad, resulting in a branched, ductal tree-like structure that fills the fat pad of the adult mammary gland.

Fig. 1.

Overview of mammary gland development. (A) A schematic diagram highlights various stages of mammary development, beginning with pubertal development, followed by each postpubertal stage. The pink shapes represent mammary fat pads, whereas the ductal epithelium is shown in purple. During pregnancy, lactation, and involution the circular objects represent lobuloalveolar units. (B) Model of mammary epithelial cell hierarchy with associated lncRNAs, mPINC and Zfas1. A bi-potent progenitor gives rise to basal and luminal progenitors during embryonic development. The luminal progenitors differentiate into mature luminal cells (hormone receptor-positive), whereas the basal progenitors differentiate into mature myoepithelial cells. Both luminal and basal progenitors may contribute to the pool of alveolar progenitors that become the milk-producing alveolar cells during lactation. Both mPINC and Zfas1 are hypothesized to maintain the alveolar progenitor cells during pregnancy and involution. This is only a proposed model; therefore, these developmental relationships still need to be further validated experimentally.

In the adult, the epithelial ducts are comprised of an inner layer of luminal epithelial cells and an outer layer of basal epithelial cells, which are thought to arise from a common bi-potent stem cell during embryonic development (Fig. 1B) (Van Keymeulen et al., 2011). The luminal cells can be further subdivided into luminal progenitors and mature luminal cells, which are differentiated hormone receptor-positive cells. The outer basal layer consists of a basal stem/progenitor cell population as well as contractile myoepithelial cells, which are necessary for pushing milk out of the alveoli and toward the nipple during lactation. Luminal and basal progenitors are thought to give rise to alveolar progenitors that, during pregnancy, begin the stepwise process of differentiation to become mature alveolar cells, which are the milk-producing cells of the mammary gland (van Amerongen et al., 2012).

The adult mammary gland can undergo multiple rounds of pregnancy, each of which requires the expansion and terminal differentiation of alveolar cells necessary for lactation, followed by their apoptotic removal during involution (Anderson et al., 2007; Brisken and Rajaram, 2006). In early pregnancy, mammary epithelial cells proliferate and expand to generate lobuloalveolar structures throughout the mammary fat pad. During mid-to-late pregnancy, proliferation rates decline as alveolar progenitors begin to differentiate and produce low levels of milk protein. However, it is not until parturition that alveolar progenitors undergo terminal secretory differentiation to produce and secrete the large volume of milk necessary to nurse offspring throughout lactation. Finally, during involution, the majority of differentiated alveolar cells undergo rounds of programmed cell death, and the gland remodels to a pre-pregnancy-like state. It has been shown that a population of mammary epithelial cells committed to an alveolar fate persists in the regressed lobules of the involuted gland, and these cells are thought to serve as alveolar progenitors in subsequent pregnancies (Boulanger et al., 2005; Wagner et al., 2002).

4. LncRNAs and mammary gland development

4.1. Mammary gland lncRNAs of unknown function

Interestingly, two of the earliest identified regulatory lncRNAs, H19 and SRA (steroid receptor RNA activator), may play a role in the developing mammary gland. The imprinted lncRNA H19 is induced by estrogen in the mouse mammary gland, and in situ hybridization shows enriched expression of H19 in mammary epithelial cells of the TEBs in pubertal mice and in the alveolar cells of pregnant mice (Adriaenssens et al., 1999). Although initially H19 was thought to only function to restrict growth during embryonic development, relatively recent data has shown an additional role for H19 in long-term maintenance of adult hematopoietic stem cells (Venkatraman et al., 2013). If H19 has an equivalent role in the mammary gland, then it may maintain stem and/or progenitor populations during the highly proliferative pubertal and pregnant stages of mammary development. Another lncRNA, SRA, has been reported to enhance proliferation, increase ductal side branching, and induce precocious alveolar differentiation when overexpressed in mammary epithelial cells of a transgenic mouse model (Lanz et al., 2003). SRA modulates the activity of nuclear hormone receptors (Lanz et al., 1999) and has been shown to regulate cell-type specific differentiation in multiple tissues (Caretti et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2010), suggesting a putative role for SRA in mammary epithelial differentiation. However, endogenous SRA transcript levels are barely detectable in the virgin mammary gland (Lanz et al., 2003), leading to questions regarding an actual function for SRA in mammary development. To validate a potential mammary function of SRA, further studies should include in-depth expression analysis at various mammary stages and mammary gland loss-of-function studies to complement the overexpression studies.

A relatively recent study also identified many additional lncRNAs putatively involved in postpubertal mammary gland development. As mentioned above, each pregnancy results in a dramatic cycle of hormonally regulated proliferation, differentiation, and programmed cell death of mammary epithelial cells. To better understand the molecular mechanisms that dictate these processes, microarray analysis was performed using RNA isolated from mammary epithelial cells from various stages of postpubertal mouse development (Askarian-Amiri et al., 2011). This study identified almost 100 differentially expressed lncRNAs between pregnant, lactating, and involuting mice, thus providing a useful resource for those studying lncRNAs in postpubertal stages of mammary development.

4.2. LncRNAs that regulate mammary epithelial differentiation

Thus far, only two lncRNAs are known to have a function in mammary epithelial cells: mPINC (mouse pregnancy-induced non-coding RNA) and Zfas1 (Znfx1 antisense 1). mPINC and Zfas1 were both identified in large-scale studies aimed at isolating differentially expressed genes during postpubertal mammary development (Askarian-Amiri et al., 2011; Ginger et al., 2001). Although mPINC and Zfas1 were characterized independently, their functions in mammary epithelial cells are quite similar. Initial in vitro studies showed that knockdown of either mPINC or Zfas1 in HC11 cells, a mammary epithelial cell line derived from a mid-pregnant mouse, led to increased proliferation, suggesting growth-suppressive roles (Ginger et al., 2006). However, further studies of these two lncRNAs suggest they play a more specialized role in the mammary gland.

mPINC and Zfas1 both show strict spatiotemporal expression during postpubertal mammary gland development (Askarian-Amiri et al., 2011; Ginger et al., 2001; Shore et al., 2012). Their expression levels increase dramatically during pregnancy, and in situ hybridization of mammary glands from mid-pregnant mice shows that mPINC is enriched in the alveolar cells, whereas Zfas1 localizes to ductal and alveolar cells. Furthermore, sorted populations of mammary epithelial cells show that mPINC is most abundantly expressed in alveolar progenitors, compared to luminal progenitors and mature luminal cells (Shore et al., 2012). In early lactation, mPINC and Zfas1 levels sharply decline, as alveolar cells undergo terminal differentiation. Accordingly, mPINC and Zfas1 levels also decline during lactogenic differentiation of HC11 cells. Furthermore, knockdown of either mPINC or Zfas1 in HC11 cells treated with lactogenic hormones enhances lactogenic differentiation, as evidenced by the increased expression of milk protein genes and the formation of domes, in vitro morphological structures associated with lactogenic differentiation. Conversely, overexpression of mPINC inhibits lactogenic hormone-induced differentiation of HC11 cells. Taken together, these data suggest that high levels of mPINC and Zfas1 during pregnancy act to repress the final step of alveologenesis, thereby maintaining an alveolar progenitor population. Additionally, the drastic reduction in their levels in early lactation may be necessary to allow terminal alveolar differentiation. Finally, mPINC and Zfas1 levels both rise again in early involution where they may act to preserve alveolar progenitors for subsequent pregnancies (Fig. 1B).

Although these in vitro data strongly suggest a role for Zfas1 during postpubertal mammary gland development, the mechanism is unknown. The Zfas1 transcript hosts three intronic snoRNAs. However, their levels are unaffected by Zfas1 knockdown, suggesting that the observed phenotypes are not regulated by the snoRNAs (Askarian-Amiri et al., 2011). Also, the lncRNA Zfas1 is transcribed antisense to the promoter of a protein-coding gene called Znfx1. Although the expression levels of Zfas1 and Znfx1 are not correlated during postpubertal mammary development, knockdown of Zfas1 in HC11 cells results in increased expression of Znfx1, suggesting that the phenotypic effects could be due, in part, to Znfx1. Further investigation into the relationship of these interconnected transcripts, as well as elucidating the mammary function of Znfx1, should lead to a better understanding of the mechanism of Zfas1.

The repression of alveolar differentiation by mPINC is likely epigenetically regulated. Like mPINC, a member of the chromatin-modifying PRC2 complex, RbAp46, is also upregulated in alveolar cells of the mammary gland during pregnancy (Ginger et al., 2001). Furthermore, RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays revealed an interaction between mPINC and RbAp46, as well as other PRC2 complex members, in HC11 cells and in mammary epithelial cells isolated from pregnant mice (Shore et al., 2012). Finally, microarray analysis of mammary epithelial cells following modulation of mPINC levels identified several potential targets of the mPINC-PRC2 complex, including Wnt4. Knockdown of mPINC leads to increased Wnt4 levels, whereas overexpression of mPINC results in decreased Wnt4 levels. Wnt4 is a plausible mediator of the observed phenotypic effects of mPINC, as it is required for alveolar development in vivo and for lactogenic differentiation in vitro (Brisken et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2006). These data suggest that a PRC2 complex that includes mPINC and RbAp46 confers epigenetic modifications to repress genes necessary for alveolar differentiation, thus maintaining a population of progenitor cells committed to an alveolar fate.

Initial studies showed potential growth-inhibitory roles of mPINC and Zfas1 in mammary epithelial cells, implying that they may function as tumor suppressors in breast cancer. mPINC and RbAp46 are both upregulated in involuted mammary glands of parous rodents compared to nulliparous mammary glands, and both have been suggested to play a role in the protective effect of pregnancy against breast cancer (Ginger et al., 2001). However, further evidence for the role of mPINC in breast cancer is currently lacking. On the other hand, there is evidence for a tumor suppressor role of Zfas1 in breast cancer that will be discussed in the next section.

5. The current state of breast cancer research

It is estimated that approximately 233,000 women in the United States will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, and an additional 63,000 women will be diagnosed with breast carcinoma in situ in 2014 (American Cancer Society, 2014). Traditionally, breast cancer has been diagnosed, categorized, and treated based on three immunohistological markers: the estrogen receptor (ER), the progesterone receptor (PR), and the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (Bertos and Park, 2011). The ER status, which generally correlates with PR status, is used to identify tumors that may respond to endocrine therapy, such as ER-antagonists and aromatase inhibitors that both function to inhibit ER-dependent signaling. Patients with HER2-positive tumors have genomic amplification and overexpression of the HER2 oncogene and are, therefore, treated with HER2 monoclonal antibodies to disrupt HER2 signaling. Breast tumors that lack ER, PR, and HER2 expression are referred to as triple-negative (TN). At present, patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) do not have a targeted therapy option and have the worst prognosis among the subtypes. Overall, mortality rates have improved in recent years with better screening programs and treatment plans. However, it is still estimated that almost 40,000 women will die this year due to breast cancer (American Cancer Society, 2014).

In the past decade, new technologies have been employed to identify gene expression signatures and genomic alterations that may be responsible for driving breast cancer progression (Ellis and Perou, 2013). Initial genomic studies of hundreds of breast tumor samples using microarray platforms have shown that breast tumors can be divided into at least four subtypes based on their distinct gene expression patterns: Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2-enriched, and Basal-like (Perou et al., 2000; Sorlie et al., 2001, 2003). Furthermore, these molecular subtypes strongly associate with patient outcome, and these data have been used to develop improved clinical assays (Prat et al., 2012). A recent study further validated and refined the four main subtypes of breast cancer by integrating data at the RNA, DNA, and protein level (Cancer Genome Atlas, 2012). Using this approach, they identified subtype-specific somatic mutations, as well as alterations in DNA copy number, DNA methylation, and mRNA and protein expression. These data provide novel subtype-specific therapeutic targets at multiple regulatory levels and emphasize the immense level of heterogeneity between tumor subtypes.

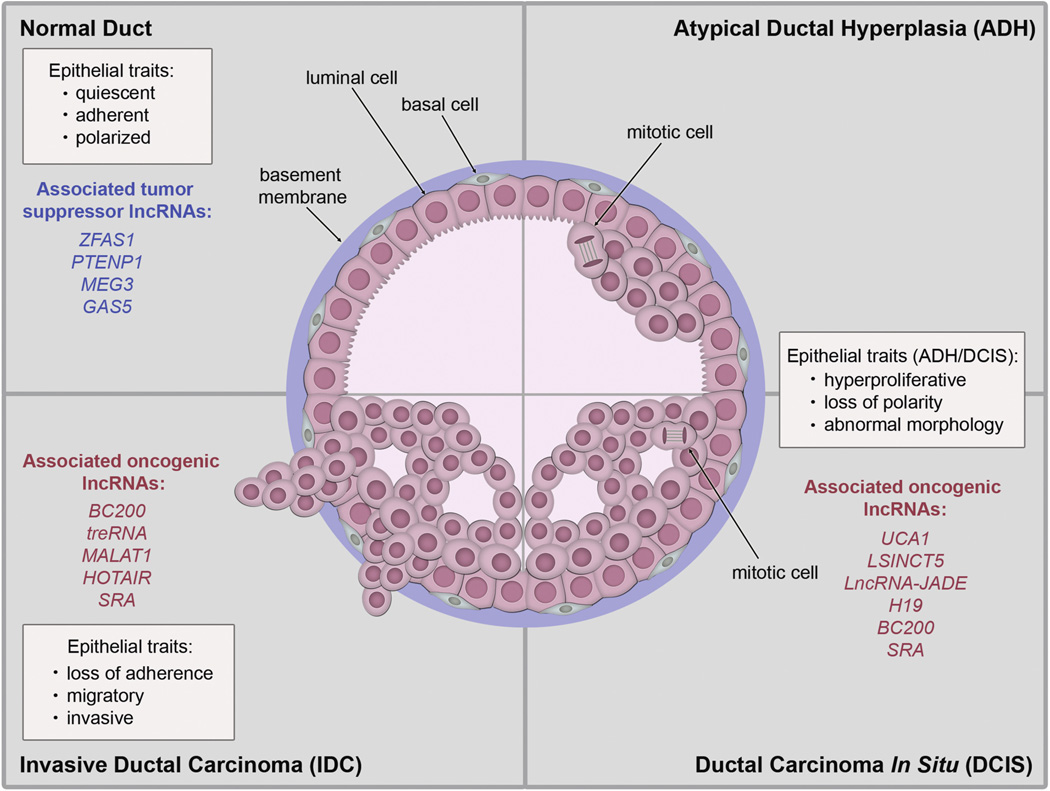

Considerable effort has also focused on understanding the early stages of breast cancer progression. The prevailing model of breast tumorigenesis assumes a linear progression from atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and then finally to invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) (Fig. 2) (Polyak, 2007). ADH is a premalignant lesion of the mammary ducts characterized by multiple layers of abnormally shaped epithelial cells that have proliferated into the lumen. ADH is thought to be the precursor of DCIS, which is a pre-invasive lesion that can progress to IDC if the epithelial cells invade through the basement membrane surrounding the mammary ducts. Following basement membrane invasion, mammary epithelial cells can travel to distant organs resulting in metastatic disease, which is the predominant cause of breast cancer related death (Eckhardt et al., 2012). Throughout the sequence of events leading to IDC and metastasis, normal epithelial functions, such as proliferation, survival, differentiation, and cell adhesion, become increasingly deregulated. Thus, identifying the molecular mechanisms involved in disrupting the intact epithelium will provide a better understanding of early tumor progression. Additionally, evidence has shown that only a subset of DCIS lesions actually progress to malignancy (Erbas et al., 2006), leading to difficult treatment decisions for DCIS patients. Therefore, determining the key genetic and epigenetic alterations that govern the critical transitions from DCIS to invasive breast cancer is another area of active investigation that will likely improve the efficacy of breast cancer treatments.

Fig. 2.

Overview of breast cancer progression. This cartoon depicts a cross section of a mammary duct divided into quadrants that represent each stage of breast cancer progression from the normal duct to ADH, then DCIS, and finally IDC. Epithelial traits and potential lncRNAs associated with the normal duct, ADH and DCIS combined, and IDC are also shown.

6. LncRNAs associated with breast cancer

6.1. Global lncRNA expression in breast cancer

The steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone and their cognate receptors, ER and PR, play complex and pivotal roles in breast cancer progression (Brisken, 2013). Numerous studies have identified thousands of estrogen-regulated lncRNAs in breast cancer cells, using a combination of GRO-seq and RNA-seq (Hah et al., 2011; Hah and Kraus, 2013; Hah et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013). These include a large group of enhancer lncRNAs (eRNAs) that are transcribed from enhancers adjacent to estrogen upregulated genes throughout the genome. Knockdown of several of these eRNAs showed that the eRNA transcripts themselves function to increase target gene activation in cis, likely by strengthening enhancer-promoter looping (Li et al., 2013). In addition, other groups have identified several lncRNAs that interact with hormone receptors and modulate their activity, some of which will be discussed below. These hormone-regulated lncRNAs, as well as lncRNA that regulate hormone receptors, could serve as additional targets to modulate hormone signaling in hormone receptor-positive breast cancers.

Recent large-scale analyses have also revealed the aberrant expression of lncRNAs in breast cancer. Some groups have used whole-genome tiling arrays to identify novel lncRNAs that show altered expression in breast tumors and cell lines (Perez et al., 2008; Silva et al., 2010). Other groups have employed sequencing-based methods and reported the differential expression of 220 lncRNAs in breast carcinomas compared to normal, as well as the identification of hundreds of additional lncRNAs specifically altered in breast tumors compared to other tumor types that could serve as breast tumor biomarkers (Brunner et al., 2012; Gibb et al., 2011b). Interestingly, one study discovered 216 lncRNAs associated with cell-cycle promoters and, of those, 35 were differentially expressed in invasive ductal breast carcinomas relative to normal breast (Hung et al., 2011). Finally, recent RNA-seq analysis of normal tissue, as well as multiple tumor types, revealed normal breast-and breast cancer-specific expression of many pseudogenes, which have been shown to also function as lncRNAs (Kalyana-Sundaram et al., 2012; Poliseno, 2012). These expression data from genome-wide studies provide a tremendous resource for those interested in pursuing the functions of individual lncRNAs, as well as for the discovery of specific biomarkers and molecular targets in breast cancer.

Several individual lncRNAs have been identified that are altered in breast cancer whose functions and mechanisms are currently unknown. In addition, there are numerous lncRNAs misexpressed in other cancers whose functions are known, but their aberrant expression in breast cancer has not been reported. For the remainder of this section, we will only focus on lncRNAs that meet the following criteria: (1) there is evidence of their misexpression in breast cancer and (2) there is evidence for a potential tumorigenic function or mechanism.

6.2. Tumor suppressor lncRNAs

The lncRNA Zfas1 is an inhibitor of mammary epithelial proliferation and differentiation that may also function as a tumor suppressor (Askarian-Amiri et al., 2011). As Zfas1 was discussed in detail in the previous section, we will only mention here that human ZFAS1 levels are reduced in the mammary epithelium of invasive ductal carcinoma samples compared to paired normal breast epithelium. This result, combined with the growth inhibitory effect of Zfas1 in mouse mammary epithelial cells, suggests that ZFAS1 could play a role in the suppression of mammary tumorigenesis.

MEG3 (maternally expressed gene 3) is an imprinted lncRNA that is expressed in most adult tissues (Zhou et al., 2012). As expected of a putative tumor suppressor gene, its expression is undetectable in a variety of primary human tumors and in all tumor cell lines tested (Zhang et al., 2003). Gain-of-function studies in vitro have shown that MEG3 inhibits growth, in part, by enhancing apoptosis (Braconi et al., 2011). Moreover, MEG3 overexpression in several cancer cell lines results in increased levels of p53 protein, as well as increased transcription of several p53 target genes, suggesting MEG3 may suppress growth via upregulation of the p53 pathway (Zhou et al., 2007). Additionally, in vivo loss of MEG3 promotes angiogenesis in the brain, suggesting that MEG3 may inhibit tumor development via repression of angiogenesis (Gordon et al., 2010). MEG3 is highly expressed in the mammary gland, but its expression is undetectable in MCF7 and T47D breast cancer cell lines (Zhang et al., 2003). Overexpression of MEG3 in MCF7 cells inhibits growth in colony formation assays, indicating a potential role for MEG3 as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer progression.

Another lncRNA with putative tumor-suppressive functions is referred to as PTENP1 (phosphatase and tensin homolog pseudo-gene 1). It is a pseudogene of the tumor suppressor protein-coding gene PTEN. In cancer cell lines, overexpression of the PTENP1 3’UTR leads to increased PTEN levels and growth inhibition, whereas PTENP1 knockdown causes decreased PTEN levels and enhanced proliferation (Poliseno et al., 2010). In addition, PTENP1 and PTEN levels are positively correlated across normal and cancer tissue samples, further suggesting that they are co-regulated. Interestingly, PTENP1 and PTEN contain common miRNA recognition elements (MREs), and it is thought that PTENP1 may function by competing for miRNA binding with PTEN, thereby relieving the repressive effects of miRNAs on PTEN. The PTENP1 locus is focally deleted in breast cancer (Poliseno et al., 2010) and the PTENP1 promoter undergoes somatic hypermethylation in breast cancer cell lines, indicating that PTENP1 loss may also contribute to breast tumor progression via epigenetic silencing (Hesson et al., 2012). Interestingly, multiple antisense lncRNAs (asRNAs) were recently identified that are also encoded from the PTENP1 locus (Johnsson et al., 2013), highlighting the complexity of the PTEN regulatory network. These asRNAs regulate both PTEN transcription and mRNA stability and are also likely to play a role in tumorigenesis.

One of the better-characterized tumor suppressor lncRNAs in breast cancer is GAS5 (growth arrest-specific transcript 5). GAS5 contains two glucocorticoid response element-like sequences that bind to the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and prevent it from interacting with its normal target genes, thus inhibiting the function of glucocorticoids through GR (Kino et al., 2010). Glucocorticoids regulate essential cellular processes, such as cell growth, metabolism, and survival. GAS5 transcript levels are significantly reduced in breast tumor samples compared to adjacent normal tissue, and overexpression of GAS5 in MCF7 breast cancer cells induces growth arrest and apoptosis (Mourtada-Maarabouni et al., 2009). Interestingly, GAS5 can also suppress the ligand-dependent transcriptional activity of other steroid hormone receptors (Kino et al., 2010), such as progesterone (PR) and androgen (AR) receptors, both of which have subtype-specific roles in breast cancer (Brisken, 2013; Chang et al., 2013; Ni et al., 2011). These data imply that the GAS5 lncRNA may have additional roles in breast cancer progression via reduced PR and AR transcriptional activity.

6.3. Oncogenic lncRNAs

The lncRNA UCA1 (urothelial carcinoma-associated 1) was originally identified as being upregulated in bladder cancer, but was recently shown to have an oncogenic role in breast cancer as well (Huang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2006). UCA1 interacts with hnRNP I (heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein I) and inhibits its normal function of binding to, and enhancing the translation of, the mRNA of the tumor suppressor p27, thereby resulting in reduced levels of p27 protein. Accordingly, there is also a negative correlation between p27 and UCA1 levels in breast tumors, suggesting that this competitive inhibition also occurs in cancer. In MCF7 breast cancer cells, overexpression of UCA1 increases cell growth, whereas knockdown of UCA1 reduces cell growth. Consistent with these data, knockdown of UCA1 in MCF7 cells transplanted into mouse mammary fat pads results in reduced tumor weight and volume, and decreased tumor cell proliferation, compared to control cells. Finally, UCA1 has also been shown to be increased in breast tumors compared to normal breast, further supporting its oncogenic function in breast cancer.

LSINCT5 (long stress-induced noncoding transcript 5) is a nuclear-enriched lncRNA that is increased in human breast and ovarian tumors compared to normal tissue samples (Silva et al., 2010). Additionally, LSINCT5 expression is high in several breast cancer cell lines, and knockdown of LSINCT5 in MCF7 breast cancer cells results in decreased proliferation (Silva et al., 2011). Microarray analysis of LSINCT5 knockdown cells showed the reduced expression of two other lncRNA transcripts, NEAT1 and MALAT1 (also referred to as NEAT2), and a protein-coding transcript, PSPC1. NEAT1 and PSPC1 are both components of nuclear paraspeckles, whereas MALAT1 is localized to nearby nuclear speckles (Bond and Fox, 2009; Mao et al., 2011). These data suggest a potential function for LSINCT5 in the regulation of these cellular compartments, which are both thought to regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally. Interestingly, MALAT1, which will be discussed in more detail below, is also overexpressed in several cancers and is thought to function as an oncogenic lncRNA (Gutschner et al., 2013a). However, it is not known whether MALAT1 mediates the oncogenic functions of LSINCT5 or if there are alternative mechanisms.

LncRNA-JADE transcription is induced by DNA damage in an ATM-dependent manner (Wan et al., 2013). Upon DNA damage, LncRNA-JADE binds to BRCA1 and enhances transcription of the neighboring protein-coding Jade1 gene, which is essential for DNA damage-induced H4 acetylation and the subsequent DNA damage response (DDR). In MCF7 breast cancer cells, knockdown of LncRNA-JADE reduces proliferation, whereas its overexpression increases proliferation. Importantly, knockdown of LncRNA-JADE also enhances DNA damage-induced apoptosis and sensitizes MCF7 cells to DNA damaging reagents. Futhermore, LncRNA-JADE knockdown in breast cancer cells orthotopically transplanted into the mouse mammary fat pad reduces tumor growth compared to control cells, and in humans, LncRNA-JADE is expressed at higher levels in breast tumors compared to normal breast. Taken together, these studies have identified a novel DDR-associated lncRNA whose aberrant expression promotes proliferation and survival of breast cancer cells, suggesting LncRNA-JADE has an oncogenic role in breast cancer.

BC200 is a primate-specific lncRNA that is normally only expressed in neurons, where it acts as a translational repressor to regulate protein synthesis at synapses (Iacoangeli and Tiedge, 2013). Interestingly, BC200 is also upregulated in several cancers, including breast cancer (Iacoangeli et al., 2004). Thorough expression analysis by in situ hybridization has shown that BC200 is increased in the epithelial cells of invasive breast cancer samples, but is undetectable in normal breast tissue. Furthermore, BC200 is also increased in high-grade (HG) DCIS, but not in non-high-grade (NHG) DCIS, suggesting that it could be used as an indicator of invasive potential in DCIS. Whether BC200 actually functions in breast cancer to regulate cell migration or invasion via translational repression is currently unknown.

The oncogenic lncRNA treRNA (translational regulatory RNA) regulates genes at both the transcriptional and translational level. In the nucleus, treRNA acts as an enhancer in cis and upregulates transcription of Snail1, a regulator of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Orom et al., 2010). In the cytoplasm, treRNA interacts with a ribonucleoprotein complex and suppresses the translation of the epithelial marker E-cadherin (Gumireddy et al., 2013), which should also promote EMT. Accordingly, overexpression of treRNA in MCF7 breast cancer cells results in decreased protein levels of E-cadherin and other epithelial markers, as well as increased protein levels of mesenchymal markers, suggesting that high levels of treRNA is able to induce a partial EMT phenotype. Overexpression of treRNA in MCF7 cells also increases cell migration and invasion in vitro, and stimulates metastasis to the lung in mouse mammary gland transplants in vivo. In further support of its oncogenic role, treRNA is significantly upregulated in paired breast cancer primary and lymph-node metastasis samples. These data suggest that treRNA could serve as a novel therapeutic target to suppress breast cancer metastasis.

The lncRNA MALAT1 (metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1, also referred to as NEAT2) was originally found to be associated with metastatic lung cancer (Ji et al., 2003), but it is also upregulated in several other tumor types, including breast tumors (Guffanti et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2007). MALAT1 localizes to nuclear speckles and interacts with several splicing factors, including SRSF1, 2, and 3 (Tripathi et al., 2010). Depletion of MALAT1 results in defective alternative splicing of a subset of transcripts, some of which are known to be involved in cancer (Lin et al., 2011), therefore, its initial ascribed function was splicing regulation. Additionally, MALAT1 has been shown to regulate gene expression by various mechanisms. For example, MALAT1 increases the expression level of several cell-cycle regulators by binding to unmethylated Pc2 and its associated cell cycle genes, and relocating them to nuclear speckles where they are actively transcribed (Yang et al., 2011). MALAT1 also regulates the expression level of the oncogene and mitosis regulator, B-MYB, by an unknown mechanism (Tripathi et al., 2013). Finally, loss of MALAT1 in vivo results in the increased expression of neighboring genes, suggesting that MALAT1 may function, in part, to repress gene transcription in cis (Zhang et al., 2012). Although the function of MALAT1 in breast cancer is not understood, recent whole genome sequencing of human breast tumor biopsies identified multiple mutations and deletions in the MALAT1 gene that are specifically associated with the Luminal B subtype of breast cancer and poor patient outcome (Ellis et al., 2012). Interestingly, these genetic alterations are in the region of MALAT1 thought to be important for its interaction with SRSF1, implicating a splicing mechanism in the potential oncogenic role of MALAT1 in luminal breast cancer.

HOTAIR (HOX antisense intergenic RNA) is one of the most extensively studied oncogenic lncRNAs in breast cancer thus far. HOTAIR is transcribed from the HOXC locus and is required for targeting the PRC2 complex to the HOXD locus in trans, resulting in chromatin compaction and transcriptional silencing of a 40 kb region of the HOXD locus (Rinn et al., 2007). Levels of HOTAIR and EZH2, a PRC2 complex member, are both increased in metastatic breast carcinomas compared to matched primary breast tumors (Chisholm et al., 2012). Furthermore, high expression of HOTAIR in breast tumors is a strong predictor of subsequent metastasis and death (Gupta et al., 2010). In breast cancer cell lines, overexpression of HOTAIR promotes invasion, whereas HOTAIR knockdown suppresses invasion. HOTAIR overexpression also promotes the metastasis of breast cancer cells orthotopically transplanted into mouse mammary fat pads to the lung in a PRC2 complex-dependent manner. HOTAIR is thought to promote metastasis by re-targeting the PRC complex to novel sites, thereby decreasing expression of associated genes. Several of these newly targeted genes have been implicated in breast cancer progression and metastasis, including HOXD10 (Carrio et al., 2005), several members of the protocadherin (PCDH) gene family (Novak et al., 2008), and EPHA1 (Fox and Kandpal, 2004). Interestingly, a recent study found that HOTAIR also competes with the tumor suppressor BRCA1 for the same binding site of EZH2, a member of the PRC2 complex (Wang et al., 2013). In breast cancer cells, expression of BRCA1 inhibits HOTAIR binding to EZH2, while depletion of BRCA1 enhances HOTAIR binding to EZH2. Depletion of BRCA1 also increases breast cancer cell migration and invasion in an EZH2-dependent manner, providing further evidence for the function of HOTAIR in breast cancer progression and metastasis.

6.4. Controversial lncRNAs in mammary tumorigenesis

H19 is transcribed from the imprinted H19/IGF2 locus and is one of the more controversial lncRNAs in cancer biology, as the debate continues regarding whether it acts as a tumor suppressor or an oncogene. Initial in vitro cancer cell line experiments, as well as more recent in vivo experiments using mouse tumor models, indicate that H19 functions as a tumor suppressor in several cellular contexts (Gabory et al., 2010). Furthermore, in early development H19 restricts embryonic growth via regulation of the nearby IGF2 gene, as well as a cohort of other imprinted genes referred to as the imprinted gene network (IGN). Interestingly, H19 also contains a miRNA, miR-675, embedded in its first exon that suppresses embryonic and placental growth by targeting and downregulating the IGF2 receptor, Igfr1 (Keniry et al., 2012). Conversely, miR-675 can also promote growth and tumorigenesis by targeting and repressing the tumor suppressor RB1 (Tsang et al., 2010). Additionally, H19 is upregulated in several tumor types, including breast tumors, indicative of an oncogenic role for H19 as well (Adriaenssens et al., 1998). In situ hybridization of breast tumor biopsies show that H19 localizes predominantly to the stromal cells, rather than the epithelium, suggesting that H19 does not function as an oncogene in the epithelium directly. However, further studies have shown oncogenic functions of H19 in mammary epithelial cells. For example, one study reported that overexpression of H19 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells decreases tumor latency and increases tumor size compared to control cells when injected into cleared mouse mammary fat pads (Lottin et al., 2002). Another study found that H19 is a direct target of the oncogenic transcription factor c-MYC in breast cancer cell lines, and that the levels of H19 and cMYC transcripts are significantly correlated in breast carcinomas (Barsyte-Lovejoy et al., 2006). In addition, siRNA knockdown of H19 reduces the clonogenicity and anchorage-independent growth of multiple breast cancer cell lines, both indicators of cellular transformation. These data provide evidence for the oncogenic role of H19 in mammary tumorigenesis, yet the mechanisms of H19 and its partner, miR-675, in the breast are still poorly understood. Also, in situ hybridization data showing increased H19 primarily in the stroma leads to questions regarding the potential roles of H19 in the stromal vs. epithelial compartments of breast tumors.

The SRA gene gives rise to both noncoding (SRA) and coding isoforms (steroid receptor RNA activator protein (SRAP)). Since the functions of SRAP have been reviewed previously (Cooper et al., 2011), and the focus of this review is on lncRNAs, we will only discuss the noncoding aspect of the SRA gene. SRA was originally identified as a novel RNA regulator of the progesterone receptor (PR) (Lanz et al., 1999), but has since been shown to bind multiple nuclear receptors (NRs) and NR co-regulators, as well as other non-NR transcription factors (Colley and Leedman, 2011). Thus, SRA is generally thought to function as a scaffolding lncRNA, often bringing together multiple transcriptional regulators at target genomic loci to modulate gene expression. SRA is expressed at very low levels in the normal breast and its expression is increased in breast tumors, particularly in PR-positive tumors (Cooper et al., 2009; Lanz et al., 1999; Murphy et al., 2000). To test the tumorigenic potential of SRA in vivo, a transgenic mouse model was created using the mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat (MMTV LTR) to drive expression of human SRA in the mouse mammary gland (Lanz et al., 2003). Overexpression of SRA results in increased PR expression and proliferation of mammary epithelial cells ultimately leading to the formation of hyperplastic lesions. However, these lesions fail to progress to malignancy. This failure is likely due to a simultaneous increase in apoptosis of epithelial cells overexpressing SRA. These data suggest that overexpression of SRA is not only insufficient to induce mammary tumor formation, but may even act to suppress tumor formation by inducing apoptosis. In the same study, SRA was shown to significantly reduce ras-induced mammary tumor formation in MMTV-SRA/MMTV-ras bigenic mice, providing further evidence for an unexpected tumor suppressor function of SRA. Conversely, a recent study showed that siRNA-induced depletion of SRA reduces the invasiveness and alters the expression of invasion-related genes in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (Foulds et al., 2010), suggesting SRA could play a role in promoting metastasis. Therefore, current data support both tumor suppressive and oncogenic functions of SRA. Ultimately, the role of SRA in tumorigenesis may be context-dependent or reflective of the levels of noncoding vs. coding isoforms (Cooper et al., 2009). Thus, further investigation is warranted into the role of this modulator of hormone NR function in breast cancer.

6.5. Potential role of lncRNAs in breast cancer progression

Although the expression of lncRNAs in various stages of breast cancer progression has not been reported, their associations with each stage can be predicted based on their tumorigenic function (Fig. 2). The tumor suppressor lncRNAs, including ZFAS1, MEG3, PTENP1, and GAS5, are expressed in the normal mammary epithelial cells and generally act as growth inhibitors. The oncogenic lncRNAs UCA1,LSINCT5, LncRNA-JADE, H19, and SRA promote proliferation of mammary epithelial cells, suggesting that they may be increased in early stages of progression, such as ADH or DCIS lesions. The increased expression of BC200 has previously been reported in both DCIS and IDC. Finally, the oncogenic lncRNAs treRNA, MALAT1, HOTAIR, and SRA promote invasion and metastasis of breast cancer cells, implicating that they play a role in later stages of progression, including IDC and metastatic disease.

7. Perspectives and future directions

7.1. In vivo function of lncRNAs

To advance our understanding of the noncoding genome and validate the relevance of lncRNAs, it is critical that we continue to elucidate their functions in vivo. Quite recently, 18 lncRNA mouse knockout models were generated that resulted in overt phenotypes, such as peri- and post-natal lethality, general growth defects, and developmental abnormalities in specific organs, thus demonstrating that lncRNAs do indeed play critical roles in vivo (Sauvageau et al., 2013). Previously, lncRNA loss-of-function mouse models were generated, but they generally lacked a notable phenotype (Lee, 2012; Mattick, 2009). This could have been due to their low abundance and strict spatiotemporal expression, thus making the phenotypes more difficult to detect. It has been suggested that more extensive phenotyping may be necessary to reveal the in vivo roles of some lncRNAs, especially to detect tissue-specific functions (Haerty and Ponting, 2013). In the mammary gland, this would include performing assays to measure stem and progenitor cell activity, such as limiting-dilution and serial transplantation assays (Visvader and Smith, 2011), in addition to observing the whole mount and histological effects of lncRNA loss-of-function during various stages of mammary development. To assess the function of tumor suppressive and oncogenic lncRNAs in vivo, lncRNA loss- and gain-of-function models should be crossed to well-characterized mouse mammary tumor models to determine effects on tumor latency, multiplicity, growth rates, and metastasis (Vargo-Gogola and Rosen, 2007). It is imperative that we have a better understanding of the in vivo roles of lncRNAs before they can be considered as valid therapeutic targets in cancer.

7.2. Identification of novel lncRNAs in mammary development and tumorigenesis

In addition to validating the functions of already known lncRNAs, current technologies, such as lncRNA microarrays and RNA-seq, should be employed to identify more cell- and stage-specific lncRNAs in mammary development and breast cancer. For example, differentially expressed lncRNAs could be identified in sorted mammary epithelial subpopulations, such as stem, basal, mature luminal, luminal progenitor, and alveolar progenitor cells. Such lineage-specific lncRNAs may act as novel regulators of stem and progenitor cell maintenance, cell fate commitment, and differentiation, and could improve our understanding of mammary gland developmental processes. Furthermore, lncRNAs are likely to be differentially expressed in the molecular subtypes of breast cancer, including Luminal A and B, Her2-enriched, and Basal-like, as well as in various stages of breast cancer progression. Identification of these lncRNAs should unveil additional subtype- and stage-specific diagnostic and therapeutic targets in breast cancer.

7.3. LncRNAs as therapeutic targets in breast cancer

In the past ten years, our understanding of RNA molecules has been drastically altered, particularly with the emergence of lncRNAs. Overwhelming evidence shows that lncRNAs are key regulators of gene expression that guide essential processes in development and tumorigenesis, suggesting that this emerging class of molecules offers a new avenue for diagnosing and treating disease. The tissue- and cancer-specific expression of lncRNAs enhances their potential use as tumor biomarkers for disease diagnosis, compared to more ubiquitously expressed genes. For example, the lncRNA PCA3 (prostate cancer gene 3) is upregulated in prostate tumors compared to normal prostate, and it is now routinely used in the clinic to aid prostate cancer diagnosis and reduce unnecessary biopsies (Lee et al., 2011). In addition, lncRNAs are unique from mRNAs in that they themselves function as the regulatory molecule, implying that measurement of their expression level is more directly indicative of their functional impact on the disease state (Cheetham et al., 2013; Sanchez and Huarte, 2013). As therapeutic targets, lncRNAs may also show increased efficacy and reduced side effects compared to more ubiquitously expressed proteins, due to their site-specific regulatory action in the genome and their strict spatiotemporal expression (Lee, 2012). For instance, a plasmid expressing diphtheria toxin under the control of the H19 promoter has been successfully used to target tumor-specific H19-expressing cells, resulting in the reduction of tumor size in clinical trials (Mizrahi et al., 2009). These early clinical applications using lncRNAs show tremendous promise for their potential use in the diagnosis and treatment of disease. Future research efforts aimed at further elucidating the molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs will advance our understanding of their roles in both development and cancer, and will facilitate the design of novel therapeutics that can alter lncRNA function.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Matthew Weston for editing the manuscript and Dr. Kevin Roarty for advice for the figures. The authors are supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute, NCI-CA16303.

Abbreviations

- lncRNA

long/large noncoding RNA

- Xist

X-inactive specific transcript

- mESC

mouse embryonic stem cell

- Evf2

embryonic ventral forebrain 2

- Six3os

sineoculis-related homeobox3 homolog, opposite strand

- Dlx1as

distal-less homeobox 1, antisense

- EGO

eosinophil granule ontogeny

- HOTAIRM1

HOX antisense intergenic RNA myeloid 1

- LincRNA-EPS

lincRNA erythroid prosurvival 1

- Lnc-MD1

long noncoding RNA, muscle differentiation 1

- ANCR

anti-differentiation noncoding RNA

- TINCR

terminal differentiation-induced ncRNA

- Bvht

braveheart

- Fendrr

Fetal-lethal noncoding developmental regulatory RNA

- SCNA

somatic copy number alteration

- PRNCR1

prostate cancer noncoding RNA 1

- PCGEM1

prostate cancer gene expression marker 1

- PANDA

p21 associated ncRNA DNA damage activated

- NF-YA

nuclear transcription factor Y, alpha

- MALAT1

metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1

- BC200

brain cytoplasmic RNA 200

- miRNA

microRNA

- piRNA

PIWI-interacting RNA

- snoRNA

small nucleolar RNA

- eRNA

enhancer RNA

- PRC2

polycomb repressive complex 2

- LSD1

lysine-specific demethylase 1

- REST

repressor element-1 (RE1) silencing transcription factor

- CoREST

co-repressor for REST

- PRC1

polycomb repressive complex 1

- MLL1

mixed lineage leukemia 1

- TEB

terminal end bud

- SRA

steroid receptor RNA activator

- mPINC

mouse pregnancy induced noncoding RNA

- Zfas1

Znfx1 antisense RNA 1

- Znfx1

zinc finger, NFX1-type containing 1

- RbAp46

retinoblastoma associated protein 46

- ER

estrogen receptor

- PR

progesterone receptor

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- TNBC

triple negative breast cancer

- ADH

atypical ductal hyperplasia

- DCIS

ductal carcinoma in situ

- IDC

invasive ductal carcinoma

- GRO-seq

global run-on sequencing

- MEG3

maternally expressed gene 3

- PTENP1

phosphatase and tensin homolog pseudogene 1

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- MRE

microRNA recognition element

- as RNA

antisense RNA

- GAS5

growth arrest-specific transcript 5

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- AR

androgen receptor

- UCA1

urothelial carcinoma-associated 1

- hnRNP I

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein I

- ATM

ataxia-telangiectasia mutated

- LSINCT5

long stress-induced noncoding transcript 5

- NEAT1 and 2

nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1 and 2

- PSPC1

paraspeckle component 1

- BRCA1

breast cancer 1, early onset

- DDR

DNA damage response

- H4

histone 4

- HG

high grade

- NHG

non-high grade

- treRNA

translational regulatory RNA

- EMT

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- SRSF1,2 and 3

serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 1, 2 and 3

- Pc2

polycomb 2 homolog

- HOTAIR

HOX antisense intergenic RNA

- EZH2

enhancer of zeste homolog 2

- PCDH

protocadherin

- EPHA1

ephrin type-A receptor 1

- IGF2

insulin-like growth factor 2

- IGN

imprinted gene network

- Igfr1

insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor

- RB1

retinoblastoma 1

- NR

nuclear receptors

- MMTV LTR

mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat

- PCA3

prostate cancer gene 3

Footnotes

This article is part of a Directed Issue entitled: The Non-coding RNA Revolution.

References

- Adriaenssens E, Dumont L, Lottin S, Bolle D, Lepretre A, Delobelle A, et al. H19 overexpression in breast adenocarcinoma stromal cells is associated with tumor values and steroid receptor status but independent of p53 and Ki-67 expression. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1597–1607. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65748-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adriaenssens EL, Duqimont S, Fauquette T, Coll W, Dupouy J, Boilly JP, et al. Steroid hormones modulate H19 gene expression in both mammary gland and uterus. Oncogene. 1999;18:4460–4473. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Estimated number of new cancer cases and deaths by sex, US, 2014. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SM, Rudolph MC, McManaman JL, Neville MC. Key stages in mammary gland development. Secretory activation in the mammary gland: it’s not just about milk protein synthesis! Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:204. doi: 10.1186/bcr1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askarian-Amiri ME, Crawford J, French JD, Smart CE, Smith MA, Clark MB, et al. SNORD-host RNA Zfas1 is a regulator of mammary development and a potential marker for breast cancer. RNA. 2011;17:878–891. doi: 10.1261/rna.2528811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Lau SK, Boutros PC, Khosravi F, Jurisica I, Andrulis IL, et al. The c-Myc oncogene directly induces the H19 noncoding RNA by allele-specific binding to potentiate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5330–5337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei MS, Ferguson-Smith AC. Mammalian genomic imprinting. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JS, Lin KK, Sonnet C, Boles NC, Weksberg DC, Nguyen H, et al. Imprinted genes that regulate early mammalian growth are coexpressed in somatic stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertani S, Sauer S, Bolotin E, Sauer F. The noncoding RNA Mistral activates Hoxa6 and Hoxa7 expression and stem cell differentiation by recruiting MLL1 to chromatin. Mol Cell. 2011;43:1040–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Bertos NR, Park M. Breast cancer – one term, many entities? J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3789–3796. doi: 10.1172/JCI57100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond AM, Vangompel MJ, Sametsky EA, Clark MF, Savage JC, Disterhoft JF, et al. Balanced gene regulation by an embryonic brain ncRNA is critical for adult hippocampal GABA circuitry. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1020–1027. doi: 10.1038/nn.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond CS, Fox AH. Paraspeckles: nuclear bodies built on long noncoding RNA. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:637–644. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger CA, Wagner KU, Smith GH. Parity-induced mouse mammary epithelial cells are pluripotent, self-renewing and sensitive to TGF-beta1 expression. Oncogene. 2005;24:552–560. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braconi C, Kogure T, Valeri N, Huang N, Nuovo G, Costinean S, et al. microRNA-29 can regulate expression of the long non-coding RNA gene MEG3 in hepatocellular cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:4750–4756. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisken C. Progesterone signalling in breast cancer: a neglected hormone coming into the limelight. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:385–396. doi: 10.1038/nrc3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisken C, Heineman A, Chavarria T, Elenbaas B, Tan J, Dey SK, et al. Essential function of Wnt-4 in mammary gland development downstream of progesterone signaling. Genes Dev. 2000;14:650–654. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisken C, O’Malley B. Hormone action in the mammary gland. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003178. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisken C, Rajaram RD. Alveolar and lactogenic differentiation. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2006;11:239–248. doi: 10.1007/s10911-006-9026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner AL, Beck AH, Edris B, Sweeney RT, Zhu SX, Li R, et al. Transcriptional profiling of long non-coding RNAs and novel transcribed regions across a diverse panel of archived human cancers. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R75. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-8-r75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabili MN, Trapnell C, Goff L, Koziol M, Tazon-Vega B, Regev A, et al. Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1915–1927. doi: 10.1101/gad.17446611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Cullen BR. The imprinted H19 noncoding RNA is a primary microRNA precursor. RNA. 2007;13:313–316. doi: 10.1261/rna.351707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candeias MM, Malbert-Colas L, Powell DJ, Daskalogianni C, Maslon MM, Naski N, et al. P53 mRNA controls p53 activity by managing Mdm2 functions. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1098–1105. doi: 10.1038/ncb1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caretti G, Schiltz RL, Dilworth FJ, Di Padova M, Zhao P, Ogryzko V, et al. The RNA helicases p68/p72 and the noncoding RNA SRA are coregulators of MyoD and skeletal muscle differentiation. Dev Cell. 2006;11:547–560. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrio M, Arderiu G, Myers C, Boudreau NJ. Homeobox D10 induces phenotypic reversion of breast tumor cells in a three-dimensional culture model. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7177–7185. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesana M, Cacchiarelli D, Legnini I, Santini T, Sthandier O, Chinappi M, et al. A long noncoding RNA controls muscle differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell. 2011;147:358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Lee SO, Yeh S, Chang TM. Androgen receptor (AR) differential roles in hormone-related tumors including prostate, bladder, kidney, lung, breast and liver. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham SW, Gruhl F, Mattick JS, Dinger ME. Long noncoding RNAs and the genetics of cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2419–2425. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm KM, Wan Y, Li R, Montgomery KD, Chang HY, West RB. Detection of long non-coding RNA in archival tissue: correlation with polycomb protein expression in primary and metastatic breast carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e47998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, Nakagawa H, Uemura M, Piao L, Ashikawa K, Hosono N, et al. Association of a novel long non-coding RNA in 8q24 with prostate cancer susceptibility. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:245–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colley SM, Leedman PJ. Steroid Receptor RNA Activator – a nuclear receptor coregulator with multiple partners: insights and challenges. Biochimie. 2011;93:1966–1972. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Guo J, Yan Y, Chooniedass-Kothari S, Hube F, Hamedani MK, et al. Increasing the relative expression of endogenous non-coding Steroid Receptor RNA Activator (SRA) in human breast cancer cells using modified oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4518–4531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Vincett D, Yan Y, Hamedani MK, Myal Y, Leygue E. Steroid receptor RNA activator bi-faceted genetic system: heads or tails? Biochimie. 2011;93:1973–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin P, Wysolmerski J. Molecular mechanisms guiding embryonic mammary gland development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003251. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien T, Johnson R, Bussotti G, Tanzer A, Djebali S, Tilgner H, et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 2012;22:1775–1789. doi: 10.1101/gr.132159.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinger ME, Amaral PP, Mercer TR, Pang KC, Bruce SJ, Gardiner BB, et al. Long non-coding RNAs in mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency and differentiation. Genome Res. 2008;18:1433–1445. doi: 10.1101/gr.078378.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinger ME, Gascoigne DK, Mattick JS. The evolution of RNAs with multiple functions. Biochimie. 2011;93:2013–2018. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djebali S, Davis CA, Merkel A, Dobin A, Lassmann T, Mortazavi A, et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. 2012;489:101–108. doi: 10.1038/nature11233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z, Fei T, Verhaak RG, Su Z, Zhang Y, Brown M, et al. Integrative genomic analyses reveal clinically relevant long noncoding RNAs in human cancer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:908–913. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt BL, Francis PA, Parker BS, Anderson RL. Strategies for the discovery and development of therapies for metastatic breast cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:479–497. doi: 10.1038/nrd2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis MJ, Ding L, Shen D, Luo J, Suman VJ, Wallis JW, et al. Whole-genome analysis informs breast cancer response to aromatase inhibition. Nature. 2012;486:353–360. doi: 10.1038/nature11143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis MJ, Perou CM. The genomic landscape of breast canceras atherapeutic roadmap. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:27–34. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbas B, Provenzano E, Armes J, Gertig D. The natural history of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97:135–144. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9101-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Bi C, Clark BS, Mady R, Shah P, Kohtz JD. The Evf-2 noncoding RNA is transcribed from the Dlx-5/6 ultraconserved region and functions as a Dlx-2 transcriptional coactivator. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1470–1484. doi: 10.1101/gad.1416106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron SR, Charalambous M, Radford E, McEwen K, Wildner H, Hind E, et al. Postnatal loss of Dlk1 imprinting in stem cells and niche astrocytes regulates neurogenesis. Nature. 2011;475:381–385. doi: 10.1038/nature10229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds CE, Tsimelzon A, Long W, Le A, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, et al. Research resource: expression profiling reveals unexpected targets and functions of the human steroid receptor RNA activator (SRA) gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:1090–1105. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox BP, Kandpal RP. Invasiveness of breast carcinoma cells and transcript profile: Eph receptors and ephrin ligands as molecular markers of potential diagnostic and prognostic application. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:882–892. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabory A, Jammes H, Dandolo L. The H19 locus: role of an imprinted non-coding RNA in growth and development. Bioessays. 2010;32:473–480. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb EA, Brown CJ, Lam WL. The functional role of long non-coding RNA in human carcinomas. Mol Cancer. 2011a;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb EA, Vucic EA, Enfield KS, Stewart GL, Lonergan KM, Kennett JY, et al. Human cancer long non-coding RNA transcriptomes. PLoS ONE. 2011b;6:e25915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginger MR, Gonzalez-Rimbau MF, Gay JP, Rosen JM. Persistent changes in gene expression induced by estrogen and progesterone in the rat mammary gland. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1993–2009. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.11.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginger MR, Shore AN, Contreras A, Rijnkels M, Miller J, Gonzalez-Rimbau MF, et al. A noncoding RNA is a potential marker of cell fate during mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5781–5786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600745103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjorevski N, Nelson CM. Integrated morphodynamic signalling of the mammary gland. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nrm3168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon FE, Nutt CL, Cheunsuchon P, Nakayama Y, Provencher KA, Rice KA, et al. Increased expression of angiogenic genes in the brains of mouse meg3-null embryos. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2443–2452. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote P, Wittler L, Hendrix D, Koch F, Wahrisch S, Beisaw A, et al. The tissue-specific lncRNA Fendrr is an essential regulator of heart and body wall development in the mouse. Dev Cell. 2013;24:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guffanti A, Iacono M, Pelucchi P, Kim N, Solda G, Croft LJ, et al. A transcriptional sketch of a primary human breast cancer by 454 deep sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumireddy K, Li A, Yan J, Setoyama T, Johannes GJ, Orom UA, et al. Identification of a long non-coding RNA-associated RNP complex regulating metastasis at the translational step. EMBO J. 2013;32:2672–2684. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464:1071–1076. doi: 10.1038/nature08975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutschner T, Diederichs S. The hallmarks of cancer: a long non-coding RNA point of view. RNA Biol. 2012;9:703–719. doi: 10.4161/rna.20481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutschner T, Hammerle M, Diederichs S. MALAT1 – a paradigm for long noncoding RNA function in cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013a;91:791–801. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutschner T, Hammerle M, Eissmann M, Hsu J, Kim Y, Hung G, et al. The noncoding RNA MALAT1 is a critical regulator of the metastasis phenotype of lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2013b;73:1180–1189. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]