Abstract

Emerging adults (ages 18 to 25) who experience multiple role transitions in a short period of time may engage in hard drug use as a maladaptive coping strategy to avoid negative emotions from stress. Given the collectivistic values Hispanics encounter growing up, they may experience additional role transitions due to their group oriented cultural paradigm. This study examined whether those who experience many role transitions are at greater risk for hard drug use compared to those who experience few transitions among Hispanic emerging adults. Participants completed surveys indicating their hard drug use in emerging adulthood, role transitions in the past year of emerging adulthood, age, gender, and hard drug use in high school. Simulation analyses indicated that an increase in the number of role transitions, from 0 to 13, was associated with a 14% (95% CI, 4 to 29) higher probability of hard drug use. Specific role transitions were found to be associated with hard drug use, such as starting to date or experiencing a breakup. Intervention/prevention programs may benefit from acknowledging individual reactions to transitions in emerging adulthood, as these processes may be catalysts for personal growth where identities are consolidated, and decisions regarding hard drug use are formed.

Keywords: Hispanic, emerging adults, drug use, role transitions, risk factors, vulnerable populations, prevention

Background

Emerging adulthood is a life stage characterized by changes in perspective, education, work, and relationships (Arnett 2011). This period is distinct from both adolescence and adulthood, where young people have more autonomy, but haven't engaged in all the responsibilities of adulthood (Arnett 2000). This time of development has implications for public health, as it marks the period in life when the risk of substance use including hard drug use (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine, MDMA or ecstasy, LSD, and inhalants) is at its highest (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2012). When emerging adults have been disaggregated by race/ethnicity, Hispanics have been described as unique because they experience a large number of transitions in emerging adulthood due to increases in their obligations toward scholastics, their jobs, and their families (Arnett 2003). Given the collectivistic values Hispanics encounter growing up, obligations towards the family may provide additional transitions (e.g., provide care giving) in emerging adulthood, which could add another layer of complexity to this period as well as stress. Role transitions (e.g., specific instability events, or disruption of daily life) have been hypothesized to increase hard drug use, among emerging adults (Arnett 2005). The stress associated with change during this period may lead emerging adults to engage in unhealthy behaviors as a maladaptive coping strategy in order to avoid negative emotions (Khantzian 1997; Sinha 2008).

Specific role transitions, including but not limited to becoming a caregiver for a family member, loss of a job, and starting to date someone new have been associated with cigarette smoking among Hispanic emerging adults (Allem et al. 2013). Similarly, specific role transitions have been associated with marijuana use and binge drinking among this target population (Allem et al. 2013a). Research, however, has not explored whether those who experience many role transitions are at greater risk for hard drug use compared to those who experience few transitions, or none at all. Understanding these associations is critical as one transition may not act to influence hard drug use decisions, but rather a series of transitions taking place all in a short period of time. Furthermore, research has not identified the specific role transitions associated with hard drug use among Hispanic emerging adults. The present study determined if the accumulated number of role transitions experienced by Hispanics in emerging adulthood was associated with hard drug use, and determined which specific role transitions were associated with hard drug use.

Methods

Participants were those who completed surveys for Project RED (Retiendo y Entendiendo Diversidad para Salud), a longitudinal study of substance use, and acculturation among Hispanics in Southern California. Participants were first enrolled in the study as adolescents, attending one of seven high schools in the Los Angeles area. The university's Institutional Review Board approved all procedures. Participants who self-identified as Hispanic were surveyed in emerging adulthood from 2010 to 2012. Tracking procedures resulted in 2,151 participants with valid contact information. A total of 1,390 (65%) emerging adults consented, and participated in the survey. Those lost to follow-up from adolescents to emerging adulthood were more likely to be male and to report hard drug use in high school, but did not differ by age.

The list of non-redundant role transitions was developed based on focus groups with Hispanic emerging adults and literature reviews (Allem et al, 2012). The survey items for these transitions were prompted with “Has this happened to you in the last year?” with responses coded 1 “Yes” or 0 “No”. The original list of role transitions was modified for the current study in order to remove two role transitions (“Became addicted to drugs or alcohol,” and “Overcame addiction to drugs or alcohol) that were conceptually related to the dependent variable. The remaining 22 items were, “Started dating someone,” “Started a new romantic relationship,” “Got engaged,” “Got married,” “Moved in with boyfriend or girlfriend,” “Broke up with boyfriend or girlfriend,” “Got legally separated from a spouse,” “Got a divorce,” “Had a baby,” “Lost a baby,” “Got a new job,” “Lost a job,” “You were demoted or forced to work fewer hours,” “You were unemployed, seeking work but unable to find it,” “Started college or new school or classes,” “Had to care for a parent or relative,” “Stopped having to care for a parent or relative,” “Had to babysit siblings or family members,” “Stopped babysitting siblings or family members,” “Got extremely ill,” “Overcame serious illness,” “Were arrested,” The total number of role transitions measure was calculated by summing the 22 individual role transitions.

The outcome variable was past-month hard drug use coded 1 “Yes” and 0 “No” where 1 indicated a participant had used at least one of the following hard drugs (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine, MDMA or ecstasy, LSD, and inhalants) in the past month. This study controlled for age, gender, and participants’ hard drug use as reported in high school in all analyses. Controlling for hard drug use in high school assured that this study was not simply describing associations among previous drug users. While all analyses were cross-sectional in nature, Project RED's data is longitudinal allowing for the inclusion of a measure of participants’ hard drug use as reported in high school. Data from participants who completed surveys in 11th grade about their hard drug use and about 3 years later in emerging adulthood (n=1,018) comprised the final sample.

Initially, bivariable associations between the accumulated number of role transitions and hard drug use were plotted using locally weighted scatter plot smoothing (lowess) as described by Cleveland (1979), and applied to substance use by Allem and colleagues (2012). Lowess is a desirable smoothing method because it tends to follow the data. This diagnostic approached demonstrated that the relationship between the accumulated number of role transitions and hard drug use was linear, and not curvilinear or some other relationship. A .80 bandwidth was used so that the associations grossly fit the general trends. Alternative bandwidths (e.g., 67 and 90) were used to verify the original patterns.

Past-month hard drug use was regressed on the total number of role transitions controlling for age, gender, and hard drug use as reported in high school. Past-month hard drug use was then regressed on each specific role transition controlling for age, gender, and hard drug use as reported in high school. To avoid multicollinearity as well as overfitting the model, 22 separate logistic regression models examined relationships between each transition, and past-month hard drug use. To control for Type I errors due to multiple tests, a Bonferonni correction was used to determine statistical significance; p-values < .002 (.05/22) were considered significant. For all analyses, quantities of interest were calculated using the estimates from each multivariable analysis by simulation using 1,000 randomly drawn sets of estimates from a sampling distribution with mean equal to the maximum likelihood point estimates and variance equal to the variance-covariance matrix of the estimates, with covariates held at their mean values (King, Tomz & Wittenberg 2000).

Results

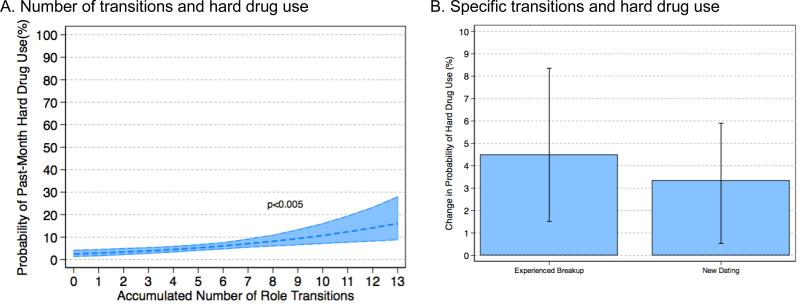

The age range among participants was 18 to 24 with a mean age of 21, and 41% were male. About 6% of participants reported past-month hard drug use, while the average number of role transitions experienced over the past year was about 5, with no one experiencing more than 13 transitions. A difference in the number of role transitions, from 0 to 13, was associated with a 14% (95% Confidence Interval [CI], 4 to 29) higher probability of hard drug use (Figure 1A). Additionally, two specific role transitions were found to be associated with past-month hard drug use. Participants who experienced a breakup in the past year were 4% (95% CI, 2 to 8) more likely to report past-month hard drug use compared with those who did not experience a breakup (Figure 1B). Participants who started to date someone new in the past year were 3% (95% CI, 1 to 6) more likely to report past-month hard drug use compared with those who did not start dating someone new.

Figure 1. Role transitions and hard drug.

(A) Shows the predicted probability of past-month hard drug use by number of role transitions. The estimates were produced by simulation using 1000 randomly drawn sets of estimates from the coefficient covariance matrix of the logistic regression model with covariates held at their mean values. (B) shows the change in predicted probability of past-month hard-drug use, with 95% confidence intervals. Estimates were calculated by simulating the first difference in each role transition e.g., dating someone new from 0 to 1. Each estimate was arrived by the use of 1000 randomly drawn sets of estimates from each respective coefficient covariance matrix with control variables held at their mean values.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the accumulated number of role transitions experienced by Hispanic emerging adults is associated with hard drug use. While previous research identified which specific role transitions have been associated with marijuana use, and binge drinking (Allem et al. 2013a), as well as cigarette use (Allem et al 2013), the present study's findings demonstrated a potential dose response relationship between the accumulated number of role transitions and hard drug use. This finding illustrates the importance of considering numerous transitions taking place in a short period of time rather than considering an individual role transition and its association with substance use in isolation. Given this growing literature, it may be pertinent to address role transitions in intervention and prevention programs among this target population in the future. Emerging adults should be warned about the possible stress from role transitions and should be taught resilience skills, or positive coping mechanisms. As emerging adults try to balance professional and personal aspirations along with romantic relationships, and obligations toward their families, they may be vulnerable to use hard drugs in order to deal with the negative emotions from stress and uncertainty.

This study also identified two specific role transitions associated with hard drug use. Romantic relationships-both starting and ending-were associated with hard drug use, which coincides with previous research on emerging adults and substance use (Cohen et al. 2003; Fleming et al 2010; Staff et al. 2010). These associations may reflect interpersonal conflicts that result from disagreement over drug use (or behaviors that occur when individuals are under the influence of drugs or trying to obtain drugs) that eventually leads to dissolution of the relationship. Alternatively, the process of a breakup could drive some emerging adults to use hard drugs in order to cope with negative affect (Cerbone & Larison 2000). Intervention and prevention programs should teach emerging adults ways to discuss sensitive topics positively, and ways to build fulfilling relationships with their significant others. Improving abilities to begin and end relationships may be of greater import than previously believed to be as these transitions may place emerging adults at high risk for hard drug use.

Research on substance use among Hispanic emerging adults is expanding but is limited in its breadth and scope. An earlier study that assessed the relationship between cultural predictors and substance use among Hispanic emerging adults reported nonsignificant associations (Venegas et al. 2010). A later study found positive value expectancy to be associated with substance use (Ceballos, Czyzewska & Croyle 2012). These studies, however, did not include measures of role transitions. A strength of the current study was its focus on characteristics unique to emerging adults and emerging adulthood. More research is needed to explore how the unique characteristics of emerging adulthood are associated with hard drug use (Stone et al. 2012), and how these associations may vary across different racial/ethnic groups (Shih et al. 2010). Future research examining Hispanic emerging adults may need to acknowledge these characteristics as possible confounders between cultural characteristics or expectancies, and hard drug use.

By disaggregating the data to distinguish emerging adults in particular, this study was able to describe certain correlates of hard drug use among a particularly vulnerable segment of the Hispanic population. Unfortunately, emerging adults are difficult to recruit for health behavior research, especially ethnic minority and low-SES emerging adults who are less likely to be enrolled full-time in college (Henrich et al. 2010; Ramo et al. 2010). Emerging adults have previously cited time constraints, communication issues, fear, and perceiving participation as unimportant as barriers to participation (Bost 2005). The current study circumvented issues of recruitment by employing data from a longitudinal study that started surveying participants in high school. Additional ways to reduce barriers to participation in research among emerging adults should be explored in the future.

Limitations of this study include measurement of role transitions and hard drug use in emerging adulthood at a single time point. Although role transitions were referenced over the past year and hard drug use was referenced over the past month, suggesting that the transitions preceded hard drug use, it is possible that hard drug use took place before the transitions. The list of role transitions in this study may not represent the array of transitions experienced by Hispanic emerging adults that could be associated with hard drug use. While the current study showed a linear relationship between the accumulated number of role transitions and hard drug use, future research should explore how role transitions may be disaggregated to create specific factors or themes, and how these potential groupings of transitions are associated with hard drug use. The measure of hard drug use did not include all known hard drugs (e.g., heroin) but did include 5 substances. Hard drug use was a dichotomous outcome limiting the understanding of frequency of use. The present study was unable to control for one's willingness to engage in risky behavior, which may confound the relationship between certain role transitions (e.g., being arrested) and hard drug use. Research should explore risk taking as a possible confounder between role transitions and hard drug use in the future. The findings presented here may not generalize to other racial/ethnic groups.

Notwithstanding these limitations the findings suggest that the number of role transitions experienced by emerging adults are significant for Hispanics and should be addressed in prevention and intervention programs. Prevention and intervention programs may benefit from acknowledging individual reactions to life events as these specific events may be catalysts for personal growth where identifies are consolidated and decisions regarding substance use are formed.

References

- Allem JP, Ayers JW, Unger JB, Irvin VL, Hofstetter CR, Hovell MF. Smoking trajectories among Koreans in Seoul and California: exemplifying a common error in age parameterization. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2012;13(5):1851–6. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.5.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem JP, Lisha NE, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB. Emerging adulthood themes, role transitions and substance use among Hispanics in Southern California. Addictive Behaviors. 2013a;38(12):2797–800. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem JP, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB. Role transitions in emerging adulthood are associated with smoking among Hispanics in Southern California. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15(11):1948–51. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Devlopment. 2003;100:63–76. doi: 10.1002/cd.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:235–54. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood(s): the cultural psychology of a new life stage. In: Jensen LA, editor. Bridging cultural and developmental approaches to psychology. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bost ML. A Descriptive Study of Barriers to Enrollment in a Collegiate Health Assessment Program. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2005;22(1):15–22. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos NA, Czyzewska M, Croyle K. College drinking among Latinos(as) in the United States and Mexico. The American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21:544–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerbone FG, Larison CL. A bibliographic essay: The relationship between stress and substance use. Substance Use & Misuse. 2000;35:757–786. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland WS. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1979;74:829–836. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Kasen S, Chen H, Hartmak C, Gordon K. Variations in patterns of developmental transitions in the emerging adulthood period. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(4):657–669. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, White HR, Oesterle S, Haggerty KP, Catalano RF. Romantic relationship status changes and substance use among 18-to-20-year-olds. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71(6):847–56. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A. The weirdest people in the world?. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2010;33:61–83. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–44. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G, Tomz M, Wittenberg J. Making the most of statistical analyses: improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science. 2000;44:341–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Reaching young adult smokers through the Internet: comparison of three recruitment mechanisms. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(7):768–775. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resor MR, Cooper TV. Club drug use in Hispanic college students. The American Journal on Addictions. 2010;19:319–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih RA, Miles JNV, Tucker JS, Zhou AJ, D'Amico EJ. Racial/ethnic differences in adult substance use: mediation by individual, family, and school factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71(5):640–651. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1141:105–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Schulenberg JE, Maslowsky J, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Maggs JL, Johnston LD. Substance use changes and social role transitions: Proximal developmental effects on ongoing trajectories from late adolescence through early adulthood. Development and Psychology. 2010;22:917–932. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AL, Becker LG, Huber AM, Catalano RF. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(7):747–75. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. SMA 12-4713) Rockville, MD: 2012. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Venegas JV, Cooper TV, Naylor N, Hanson BS, Blow JA. Potential cultural predictors of heavy episodic drinking in Hispanic college students. The American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21:145–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]