Abstract

Background

HIV infection is associated with a higher prevalence of low bone mineral density (BMD) and fractures than the general population. There are limited data in HIV-positive adults, naïve to antiretroviral therapy (ART), to estimate the relative contribution of untreated HIV to bone loss.

Methods

The START Bone Mineral Density substudy is a randomised comparison of the effect of immediate versus deferred initial ART on bone. We evaluated traditional, demographic, HIV-related, and immunological factors for their associations with baseline hip and lumbar spine BMD, measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, using multiple regression.

Results

A total of 424 ART-naïve participants were enrolled at 33 sites in six continents; mean (SD) age was 34 (10.1) years, 79.0% were nonwhite, 26.0% were women, and 12.5% had a body mass index (BMI) <20 kg/m2. Mean (SD) Z-scores were -0.41 (0.94) at the spine and -0.36 (0.88) for total hip; 1.9% had osteoporosis and 35.1% had low BMD (hip or spine T-score <-1.0). Factors independently associated with lower BMD at the hip and spine were female sex, Latino/Hispanic ethnicity, lower BMI and higher estimated glomerular filtration rate. Longer time since HIV diagnosis was associated with lower hip BMD. Current or nadir CD4 cell counts, and HIV viral load were not associated with BMD.

Conclusions

In this geographically and racially diverse population of ART-naïve adults with normal CD4 cell counts, low BMD was common, but osteoporosis was rare. Lower BMD was significantly associated with traditional risk factors but not with CD4 cell count or viral load.

Keywords: HIV, antiretroviral therapy, ART-naïve, bone mineral density

Introduction

Cross-sectional studies have reported a higher prevalence of low bone mineral density (BMD), osteoporosis and fractures in HIV-positive adults compared with HIV-negative controls (1, 2). Risk factors reported for low BMD and fractures in the general population have also been associated with low BMD and fractures in HIV-positive adults. These include older age, female sex, low weight or body mass index (BMI), hypogonadism or menopause, smoking, higher alcohol intake, chronic hepatitis C infection and glucocorticoid use (3-7).

In addition, initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) is consistently associated with a 2-6% reduction in BMD, mainly over the first year of ART, with stabilisation thereafter in the majority of studies (1, 8, 9). Bone loss is greater with the use of particular antiretroviral drugs, e.g., tenofovir and ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors (7, 8, 10). It has also been hypothesised that this loss is due to increased bone catabolism following suppression of HIV viral load and increase in CD4 cell count (11, 12).

Limited data raise the possibility that untreated HIV infection might directly lower BMD. Reports of direct HIV-1 infection of osteoblasts are inconsistent (13-15). A rat transgenic model of HIV infection results in low BMD, perhaps because of altered B-lymphocyte production of two proteins - a decrease in osteoprotegerin and increase in receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) production - resulting in greater bone resorption. The rat model is also associated with wasting, which could contribute to bone loss (16). A study in ART-naïve men also reported that those with low BMD had a low osteoprotegerin/ RANKL ratio (15). The close association between bone metabolism and immune activation/chronic inflammation is seen in other diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, that are also associated with low BMD and increased fracture risk (17, 18).

The contribution of untreated HIV infection to BMD loss in HIV-positive people with normal CD4 cell counts is unclear. A small age-, sex- and race-matched prospective cohort study that recruited ART-naïve adults with normal CD4 cell counts reported no difference in BMD at either the hip or the spine compared with HIV-negative individuals (19). Most patients now initiate ART well before HIV wasting develops and BMI falls. If HIV directly affects BMD, then HIV-related parameters, such as HIV duration, lower CD4 cell count and higher HIV viral load, might, in addition to traditional risk factors, be associated with lower BMD. No consistent relationship has been found, however, between HIV viral load, HIV-induced immune deficiency or HIV-related immune activation and low BMD in cross-sectional studies (20-23). Additionally, a small study of young adults with recent HIV infection found no difference in BMD relative to uninfected controls, suggesting that any effect of HIV on BMD is not acute (24). There are no data from a randomised trial comparing the effect of ART to no ART on the rate of bone loss in individuals with HIV.

The abovementioned studies evaluating BMD risk factors in ART-naïve, HIV-positive adults are limited by relatively small sample size, recruitment in a limited geographic region and evaluation of only some potential risk factors. In contrast, participants enrolling into the Bone Mineral Density Substudy of the Strategic Timing of AntiRetroviral Treatment (START) study constitute a larger, geographically diverse cohort in which all major risk factors for low BMD are recorded. Therefore, we assessed the prevalence of low BMD in participants entering this substudy and examined the association of traditional osteoporosis risk factors as well as HIV parameters with low BMD.

Methods

Study objectives

The START Bone Mineral Density Substudy will evaluate the relative contributions of HIV and initial ART by comparing an immediate to a deferred ART strategy with respect to rate of change in hip and spine BMD. We hypothesised that immediate ART will cause greater BMD loss than deferred ART. The coprimary outcomes are the change from baseline in total hip BMD and lumbar spine BMD as measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Secondary outcomes include change in femoral neck BMD from baseline and the incidence of osteoporosis or low BMD.

The objectives of the present analysis are to assess the prevalence of low BMD in START Bone Mineral Density Substudy participants and to examine the association of traditional osteoporosis risk factors and HIV parameters with BMD at the hip and spine in ART-naïve adults with normal CD4 cell counts.

Study population

Bone Mineral Density Substudy participants were coenrolled in the START study at 33 clinical sites in 11 countries (Australia, Belgium, Brazil, India, Ireland, Peru, South Africa, Spain, Thailand, United Kingdom, United States) between June 2011 and June 2013. At these sites, all eligible potential participants were offered coenrolment. Eligibility criteria were broad, and excluded only individuals who were currently receiving drug treatment for low BMD (calcium, vitamin D and hormone replacement therapy were permitted) or for whom valid BMD data could not be obtained by DXA: weight greater than 136 kg; height greater than 198 cm; implants in one or more measurement areas (L1 to L4 vertebrae, both hips); prior hip or spine surgery, severe degenerative or arthritic disease of the spine or hip, or moderate to severe scoliosis. The study design, eligibility criteria, site selection and sample size for the START trial are described elsewhere (25).

All participants provided written, informed consent prior to enrolment.

BMD scans

BMD at the hip and lumbar spine (L1-L4) were assessed by DXA using a standardised protocol within 120 days prior to randomisation and will be assessed annually until the closing of the parent START study. Each of the 16 radiology centres used either a Hologic (Hologic Inc., Bedford, Massachusetts, United States; n=290 participants) or a GE Lunar (GE Healthcare, Madison, Wisconsin, United States; n=134) scanner to measure BMD. All DXA images are read centrally at the study's DXA quality assurance (QA) centre at the University of California, San Francisco, California, United States.

QA measures for BMD readings

Prior to study commencement, each radiology centre was certified by the DXA QA centre; this included certification of the scanning equipment and of at least two technicians for performing standardised DXAs. Certification of technicians included an online evaluation that tested knowledge of the study manual, successful scans of five volunteers not participating in the study, evaluated at the DXA QA centre, and proof of professional certification.

In order to ensure complete baseline BMD data, the quality of each scan submitted by each radiology centre was evaluated immediately at the QA reading centre. Unacceptable quality scans were to be repeated as soon as possible, and no later than four months postrandomisation.

BMD measures obtained on GE Lunar equipment were standardised to Hologic measures using validated linear transformation equations (26, 27). The DXA QA centre standardised all baseline scans for cross-sectional consistency, using two types of phantom scans: first, phantoms provided by the DXA equipment manufacturers were scanned prior to each participant scan, and at least three times a week; second, a set of three cross-calibration phantoms were circulated to each radiology centre.

BMD outcome measures

T-scores and Z-scores were calculated at the DXA QA centre from the cross-sectionally adjusted BMD readings. T-scores were calculated relative to peak bone mass in young white women; a T-score of -1 denotes a BMD that is 1 standard deviation below the mean BMD of the reference population. Z-scores were calculated relative to reference populations matched by age, sex and race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic). T-scores and Z-scores for hip scans were calculated based on US National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey III data (28), while Hologic's reference data were used for spine BMD (29).

We considered two definitions of low BMD and osteoporosis: first, if the T-score at the femoral neck was at or below -1 SD or -2.5 SD, respectively; second, if the T-score at any of the three locations (femoral neck, total hip or lumbar spine) was at or below -1 SD or -2.5 SD, respectively. The first definition was used because the WHO Fracture Risk Algorithm (FRAX®) equations relate femoral neck BMD T-scores to fracture risk for postmenopausal women and men above age 50 (www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX). The second definition is consistent with the classification by the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) (30).

Statistical analyses

We calculated means and standard deviations (SDs) for the BMD values, T-scores, and Z-scores obtained at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck, and estimated prevalence of low BMD and osteoporosis, overall and by geographic region. We compared mean BMD and prevalence of low BMD/osteoporosis between geographic regions using Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA), adjusted for age (categories 18-29, 30-39, 40-49, ≥50 years), sex and menopausal status. In order to aid the interpretation of regional differences in mean BMD, we summarised demographics, season of recruitment, and HIV-related factors as well as other clinical and laboratory factors by region of enrolment.

We estimated associations of baseline factors with BMD in separate linear regression models that were adjusted for age, sex and menopause status, as well as in joint multivariable models. We chose to model BMD rather than T-scores or Z-scores, because T-scores are linear transformations of the BMD values and as such would yield similar results, and because the Z-score calculations are less transparent compared with the original BMD measures as they use age, sex and race-matched reference populations.

The multivariable models were determined, separately for lumbar spine, total hip and femoral neck, by backwards variable selection with the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (31), starting with a model containing all covariates and stepwise eliminating factors that did not contribute to the model fit. The backwards selection procedure was used because many of the factors are correlated. Initially, we included the following factors: demography (age, sex, menopause status, race/ethnicity, geographic region of enrolment; these factors were retained for all models and not subject to elimination), scanner type (Hologic or GE Lunar); season of enrolment; current smoking, BMI, diabetes mellitus, liver disease, hepatitis B or C, alcohol or recreational drug use (moderate to excessive alcohol use defined as consuming two or more drinks on 4-7 days of the week (32)); drug therapy use (vitamin D3, calcium supplements, hormone replacement therapy, proton pump inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]); HIV disease characteristics (time since HIV diagnosis, CD4 lymphocyte count, nadir CD4 lymphocyte count, CD8 lymphocyte count, log10 plasma HIV viral load); and baseline pathology (haemoglobin, alkaline phosphatase, total cholesterol, triglycerides, estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease [MDRD] formula (33), and proteinuria by urine dipstick [trace or higher]). As a final step, we eliminated factors with p-values >0.10. We presented graphically the regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals for those factors that were independently associated with BMD in the final multivariable models for BMD at the spine, total hip or femoral neck.

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States). All p-values are two-sided; p≤0.05 denotes significance.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the 424 participants overall and by region are shown in Table 1. Most participants were recruited in South America and Asia; about 30% were Asian, 26% were Latino/Hispanic, 18% were black. In terms of conventional risk factors for low BMD, mean age was 34 years (SD 10.1), 25.9% were women (12.7% of women were postmenopausal), 19.8% were current smokers, 4.2% consumed at least two alcoholic drinks on at least four days per week (moderate to excessive alcohol use), 3.3% reported a prior fracture occurring over the age of 18 years after no or minimal trauma, and 12.7% had a BMI less than 20 kg/m2. Nineteen participants (4.5%) were taking a calcium supplement, 23 (5.4%) a vitamin D supplement, and 1 (0.2%) was treated with corticosteroids. Many baseline characteristics varied substantially between regions of enrolment; for example, the proportion of women varied from 12% in South America to 78% in South Africa; the proportion of smokers varied from 11% in South Africa to 44% in the United States, and vitamin D supplementation was substantially higher in the United States (44% versus ≤7% in all other regions).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by geographic location

| Baseline variable | South America | Asia | Australia and Europe | South Africa | United States | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 163 | 128 | 71 | 46 | 16 | 424 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (years; mean, SD) | 30 (7.5) | 34 (9.7) | 40 (11.1) | 39 (10.1) | 40 (10.7) | 34 (10.1) |

| Sex and menopausal status (%) | ||||||

| Men | 87.7 | 71.1 | 87.3 | 21.7 | 50.0 | 74.1 |

| Premenopausal women | 11.7 | 25.8 | 11.3 | 63.0 | 43.8 | 22.6 |

| Postmenopausal women | 0.6 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 15.2 | 6.3 | 3.3 |

| Race (%) | ||||||

| Black | 9.8 | 0.0 | 9.9 | 93.5 | 62.5 | 17.9 |

| Latino/Hispanic | 60.1 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 37.5 | 25.5 |

| Asian | 0 | 97.7 | 2.8 | 0 | 0 | 30.0 |

| White | 20.2 | 1.6 | 77.5 | 0 | 0 | 21.2 |

| Other | 9.8 | 0.8 | 4.2 | 6.5 | 0 | 5.4 |

| Season of recruitment (%) | ||||||

| Summer-Autumn | 51.5 | 44.5 | 43.7 | 43.5 | 43.8 | 46.9 |

| Winter-Spring | 48.5 | 55.5 | 56.3 | 56.5 | 56.3 | 53.1 |

| Clinical | ||||||

| Smoking status (%) | ||||||

| never smoked | 73.6 | 68.8 | 56.3 | 82.6 | 31.3 | 68.6 |

| ex-smoker | 12.9 | 8.6 | 14.1 | 6.5 | 25.0 | 11.6 |

| current smoker | 13.5 | 22.7 | 29.6 | 10.9 | 43.8 | 19.8 |

| Alcohol usea (%) | 2.5 | 5.1 | 10.4 | 0 | 0 | 4.2 |

| Current recreational drug useb (%) | 6.1 | 6.1 | 12.3 | 0 | 13.3 | 6.7 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 0.0 | 1.6 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 6.3 | 1.9 |

| Chronic liver disease, cirrhosis or hepatic steatosis | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.3 | 0.5 |

| Weight (kg; mean, SD) | 71.4 (12.5) | 62.1 (9.8) | 77.1 (14.3) | 78.4 (19.0) | 79.4 (18.2) | 70.6 (14.6) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2; mean, SD) | 24.8 (3.8) | 22.5 (3.6) | 25.4 (4.7) | 29.8 (6.0) | 28.7 (7.0) | 24.9 (4.9) |

| Menopause (% of females) | 5.0 | 10.8 | 11.1 | 19.4 | 12.5 | 12.7 |

| Hepatitis B (%) | 2.5 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 0 | 3.3 |

| Hepatitis C (%) | 1.8 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 4.3 | 25.0 | 3.3 |

| Previous fracture (%) | ||||||

| Any | 6.1 | 3.1 | 23.9 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 8.3 |

| Fragility fracturec | 3.1 | 1.6 | 9.9 | 0 | 0 | 3.3 |

| Current Medication Use | ||||||

| Corticosteroids (%) | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Calcium supplements (%) | 2.5 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 37.5 | 4.5 |

| Vitamin D3 (%) | 2.5 | 5.5 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 43.8 | 5.4 |

| Proton pump inhibitors (%) | 1.2 | 0 | 7.0 | 2.2 | 0 | 1.9 |

| Hormone replacement therapy (%) | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 6.3 | 0.5 |

| NSAID (%) | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 6.5 | 18.8 | 1.9 |

| HIV-related | ||||||

| Mode of HIV infection (%) | ||||||

| injection drug use | 0 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0 | 12.5 | 0.9 |

| same sex contact | 82.2 | 50.0 | 80.3 | 0 | 37.5 | 61.6 |

| opposite sex contact | 16.6 | 39.8 | 14.1 | 87.0 | 50.0 | 32.1 |

| Other | 1.2 | 9.4 | 4.2 | 13.0 | 0 | 5.4 |

| Time since HIV diagnosis (years; mean, SD) | 0.9 (1.1) | 2.6 (3.6) | 2.2 (2.6) | 3.7 (3.3) | 8.9 (8.8) | 2.2 (3.5) |

| CD4 count (cells/μ,L; mean, SD) | ||||||

| Current | 682 (152) | 667 (134) | 727 (163) | 692 (156) | 724(205) | 688 (152) |

| Nadir | 582 (122) | 588 (142) | 578 (159) | 599 (149) | 576 (175) | 585 (139) |

| CD8 count (cells/μL; mean, SD) | 1135 (543) | 1196 (491) | 1271 (628) | 1036 (393) | 1227 (802) | 1169 (543) |

| HIV viral load (log10 copies/mL plasma; mean, SD) | ||||||

| Current | 4.1 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.0 (0.8) | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.6 (1.0) | 4.1 (0.9) |

| highest ever | 4.3 (0.8) | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.5 (0.9) | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.9 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.9) |

| HIV viral load >100,000 copies/mL plasma (%) | 14.7 | 17.6 | 12.7 | 15.2 | 0 | 14.7 |

| Laboratory Test | ||||||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL; mean, SD) | 14.8 (1.3) | 14.1 (1.4) | 14.6 (1.4) | 13.2 (1.7) | 12.6 (1.6) | 14.3 (1.5) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L; mean, SD) | 84 (22) | 104 (102) | 81 (36) | 68 (19) | 87 (23) | 88 (61) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL; mean, SD) | 166.6 (35.0) | 187.9 (34.1) | 181.3 (43.9) | 155.5 (39.5) | 166.7 (32.5) | 174.3 (38.3) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL; mean, SD) | 105.3 (30.7) | 117.9 (31.3) | 111.5 (32.7) | 95.5 (32.2) | 95.9 (33.9) | 108.7 (32.2) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL; mean, SD) | 37.9 (9.9) | 45.7 (12.3) | 44.7 (14.8) | 44.4 (12.3) | 47.5 (9.1) | 42.5 (12.3) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL; mean, SD) | 119.4 (82.6) | 126.5 (100.6) | 128.3 (83.6) | 77.3 (33.3) | 117.5 (85.7) | 118.4 (86.0) |

| eGFR (mean, SD) | 110(24) | 105 (20) | 102 (21) | 138 (29) | 107 (18) | 110 (25) |

| Proteinuria (%) | ||||||

| Negative | 92.0 | 84.4 | 81.7 | 91.3 | 50.0 | 86.3 |

| Trace | 3.7 | 8.6 | 15.5 | 0.0 | 31.3 | 7.8 |

| 1+ or higher | 4.3 | 7.0 | 2.8 | 8.7 | 18.8 | 5.9 |

Consumes alcohol 4-7 days a week with at least 2 drinks per day

Using at least once in the past month

Fragility fracture defined as fracture occurring following a fall from standing height or equivalent. All fractures occurred after the age of 18 years

Abbreviations NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Spine DXA scans were analysable for 423 (99.8%) participants; for three participants, scans were obtained after baseline (range 9-14 days), but only one had started ART by the time of the scan. Analyses for hip BMD include 421 (99.3%) participants; for two participants, scans were not analysable due to poor quality, and one participant was excluded because the scan was obtained after six months of ART use. Of those included, five hip scans were obtained after randomisation, but only two participants had started ART (5 and 16 days).

Mean baseline BMD, T-scores and Z-scores at the total hip, lumbar spine and femoral neck overall and by geographic region are shown in Table 2. Prevalence of osteoporosis was low, only 1.9% had a T-score ≤-2.5 at the hip or spine, 0.5% had a femoral neck T-score ≤ -2.5. Low BMD (femoral neck, total hip or lumbar spine T-score <-1.0) was found in 165 (35.1%) participants.

Table 2.

Bone mineral density, T-scores and Z-scores by geographic location.

| Characteristic | Total | South America | Asia | Australia and Europe | South Africa | United States | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 423 | 163 | 128 | 70 | 46 | 16 | |

| Spine (L1 to L4) | |||||||

| BMD (g/cm2) | 1.02 (0.13) | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.06 | 0.09 |

| T-score | −0.21 (1.20) | −0.07 | −0.44 | −0.07 | −0.35 | 0.14 | 0.09 |

| Z-score | −0.54 (1.22) | −0.48 | −0.61 | −0.31 | −1.02 | −0.31 | 0.002 |

| Total hip | |||||||

| BMD (g/cm2) | 0.96 (0.13) | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 1.03 | <0.001 |

| T-score | 0.17 (1.06) | 0.23 | −0.16 | 0.23 | 0.57 | 0.73 | <0.001 |

| Z-score | −0.36 (0.88) | −0.46 | −0.47 | −0.20 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Femoral neck | |||||||

| BMD (g/cm2) | 0.85 (0.13) | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.93 | <0.001 |

| T-score | 0.00 (1.16) | 0.11 | −0.23 | −0.20 | 0.35 | 0.77 | <0.001 |

| Z-score | −0.41 (0.94) | −0.54 | −0.42 | −0.32 | −0.26 | 0.12 | 0.16 |

| Low BMDa (%) | 18.8 | 17.9 | 28.9 | 14.5 | 6.5 | 0.0 | <0.001 |

| Low BMDb (%) | 35.1 | 32.7 | 45.3 | 27.1 | 30.4 | 25.0 | 0.04 |

| Osteoporosisc (%) | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.85 |

| Osteoporosisd (%) | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.93 |

Values are mean (SD) unless shown as percentages. P-values are adjusted for age category, sex and menopausal status. T-scores are relative to young adult white women. Z-scores are age, sex and race matched.

% with femoral neck T-score < −1.0

% with femoral neck, total hip or lumbar spine (L1 to L4) T-score < −1.0

% with femoral neck T-score < −2.5

% with femoral neck, total hip or lumbar spine (L1 to L4) T-score < −2.5

Abbreviations: BMD = Bone mineral density; SD = standard deviation.

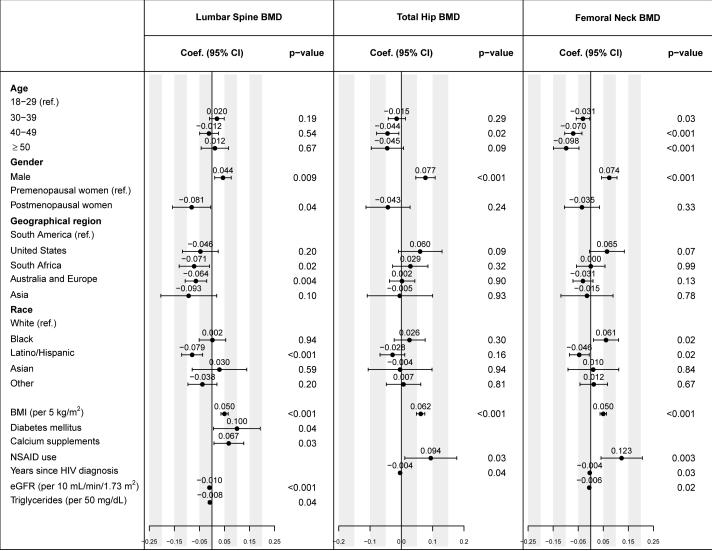

Figure 1 and supplemental Table S1 display the estimated regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (standard errors in Table S1) for the factors that were independently associated with BMD, at the spine, total hip, or femoral neck. Female sex and lower BMI were independently associated with lower BMD at each skeletal site. Postmenopausal women had lower BMD than premenopausal women, but the difference was significant only at the spine. Older age was associated with lower BMD at the hip, but not at the spine. Latino/Hispanic ethnicity was associated with lower BMD at the spine (p<0.001 compared with white) and femoral neck (p=0.02). Higher eGFR levels were associated with lower BMD (p<0.001 at the spine, p=0.02 at the femoral neck). Use of calcium supplements (p=0.03) and lower triglycerides were borderline associated with higher spine BMD (p<0.04), use of NSAIDs with higher hip BMD (p=0.03 and 0.004 at the total hip and femoral neck, respectively).

Figure 1.

Associations of baseline factors with BMD measured at the lumbar spine (L1-L4), total hip and femoral neck. Estimated coefficients from multivariable linear regression models are presented with 95% confidence intervals; factors with p-values ≤ 0.05 are independently associated with BMD.

Abbreviations: BMD=bone mineral density; BMI=body mass index; CI=confidence interval; coef.=regression coefficient; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; NSAID=nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Footnote:

Multivariable models were determined by backwards variable selection, and factors with p-values >0.10 were excluded from the final models; the following factors were investigated but were not significant (excluded by the variable selection procedure or p>0.05): scanner type (Hologic or GE Lunar); season of enrolment; current smoking, liver disease, hepatitis B or C, alcohol or recreational drug use; use of vitamin D3, hormone replacement therapy, proton pump inhibitors; CD4 cell count, nadir CD4 cell count, CD8 cell count, log10 plasma HIV viral load; total cholesterol, haemoglobin, alkaline phosphatase, and proteinuria by urine dipstick. Age, sex, menopause status, race/ethnicity and geographical region were included a priori in all models. In addition to the displayed variables, the model for total hip BMD was adjusted for baseline CD4 and nadir CD4 cell counts (p=0.09 for each) and baseline eGFR (p=0.07).

Among the HIV-related factors, there was no association of BMD with either CD4 cell count or nadir CD4 cell count. Longer duration of HIV infection (time since HIV diagnosis) was associated with lower hip BMD (estimated regression coefficient of -0.004 g/cm2 per year for total hip and femoral neck, each), but not with spine BMD.

Univariable associations, adjusted for age, sex and menopause status, are summarised in the supplemental Table S2.

Discussion

In this geographically and ethnically diverse population of ART-naïve, HIV-positive adults with normal CD4 cell counts, we found that low BMD was common (35.1%), but osteoporosis was rare (1.9%). Low BMD was significantly and independently associated with traditional risk factors (female sex, menopause, low BMI, older age), and region of recruitment. Low BMD was independently associated with time since diagnosis of HIV infection (0.004 g/cm2 lower per year at the total hip and femoral neck), but not with nadir or current CD4 cell count or HIV viral load.

The prevalence of low BMD in our study (35%) is similar to those reported in other cohorts of ART-naïve adults (20-23). The largest of these studies reported that women had significantly lower Z-scores than men at the lumbar spine and total hip (21); we also found an additional independent association of low BMD at the spine with menopause. Brown et al (21) reported a significant independent relationship between low BMD and both low total lean mass and total fat mass. We have not measured soft tissue in the Bone Mineral Density Substudy, but did find a relationship between low BMI and low BMD.

The START Bone Mineral Density Substudy is the first study to evaluate BMD in ART-naïve adults across more than one region; we found significant geographic differences, with significantly greater proportion of participants with low BMD in Asia (Table 2). There was a higher prevalence of osteoporosis in Australia/Europe, and more previous fractures were reported from this region as well. This may be explained by the older age and greater proportion of white participants in this region. Others have also shown an increased prevalence of osteoporosis and fractures for older age and white race (34).

We did not find a significant association between CD4 cell count and BMD. The fact that our study population all had normal CD4 cell counts (>500 cells/μL), may have limited our capacity to show such an association. However, Brown et al (21), whose patients had a much lower mean CD4 cell count (349 cells/μL), also did not identify any independent association of BMD with CD4 cell counts or HIV viral load. The association of hip BMD with the time since HIV diagnosis, albeit significant, is weak (0.004 g/cm2 lower hip BMD per year since diagnosis, which is 3.1% of 1 SD of the baseline BMD).

Lower eGFR was associated with higher BMD at the lumbar spine and femoral neck, although not at the total hip. This finding is counterintuitive with no clear explanation, as most studies report lower BMD with significant loss of renal function (35). The younger population recruited to the START Bone Mineral Density Substudy had normal renal function. It is possible that this finding is an artefact.

Our analysis has several limitations. Our sample size was not driven by any statistical power to identify risk factors. We analysed many covariates; some of the observed associations may be spurious. Furthermore, recruitment, although geographically widespread, was uneven across sites and countries; estimates of prevalence of low BMD in the United States in particular are uncertain (16 participants). Due to confounding, associations of race and geographical region with BMD may have been masked in the multivariable regression. Scans were obtained at 16 different radiology centres. BMD readings were calibrated for cross-sectional consistency by the DXA QA centre through use of regular local phantom scans as well as scans of cross-calibration phantoms; scan methodology and training of radiology technicians were standardised; and the regression models were adjusted for region of enrolment. Also, our analysis was cross-sectional; consequently, results provide no evidence for temporal relationships and may be influenced by selection bias resulting from eligibility criteria and screening processes.

In addition, the definition of osteoporosis by T-score <-2.5 is validated only for postmenopausal women and men over the age of 50 years, through large studies that correlate BMD to fracture risk. Our population is substantially younger; no data are available that tie T-scores or Z-scores to bone quality and fracture risk for this young population. The NOF suggests that BMD in younger adults should be interpreted using Z-scores, which compare BMD to an age, gender and race-adjusted cohort rather than peak BMD for white women. In our study population, 11.4% of participants have Z-scores < -2, the cutoff recommended by NOF.

While the majority of studies have reported that HIV is a risk factor for low BMD, debate continues as to whether HIV is an independent risk factor or if its effect is mediated through other associations with HIV, namely lower BMI (36). There is increasing evidence that after adjustment for demographic and lifestyle factors and BMI, HIV is an independent risk factor for low BMD (35). The planned longitudinal follow-up of these geographically and racially diverse participants, randomised to immediate ART versus deferred ART in the START study, provides a unique opportunity to understand the natural history of untreated HIV versus that of treated HIV on bone mass and incident fractures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants, site coordinators and investigators, and staff at the radiology sites, the coordinating centres, and the UCSF DXA QA Centre. See INSIGHT START Study Group, 2015, this supplement for a complete list of START investigators.

Funding

The START study is primarily funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UM1-AI068641, the Department of Bioethics at the NIH Clinical Center and five NIH institutes: the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal disorders. Financial support is also provided by the French Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA et les Hépatites Virales (ANRS), the German Ministry of Education and Research, the European AIDS Treatment Network (NEAT), the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, and the UK Medical Research Council and National Institute for Heath Research. Six pharmaceutical companies (AbbVie, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline/ViiV Healthcare, Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp.) donate antiretroviral drugs to START.

Footnotes

The START study is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00867048).

Disclosures

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The University of Minnesota, the sponsor of START, receives royalties from the use of abacavir, one of the HIV medicines that can be used in START.

Potential conflicts of interest

AC has received research funding from Baxter, Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer and ViiV Healthcare; consultancy fees from Gilead Sciences, MSD, and ViiV Healthcare; lecture and travel sponsorships from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, MSD, Roche, and ViiV Healthcare; and has served on advisory boards for Gilead Sciences, MSD, and ViiV Healthcare. JH's institution has received funding for her participation in Advisory Boards for Gilead Sciences, MSD, and ViiV Healthcare. JIB has received consultancy fees from Gilead Sciences, MSD and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and lecture sponsorship from Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Abbvie and ViiV Healthcare. KE has received travel support from Merck Sharp & Dohme for attendance at DMC meetings. BG, JN, AA, SBF, DW and AS declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Brown TT, Qaqish RB. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic review. AIDS. 2006;20:2165–2174. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801022eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Triant VA, Brown TT, Lee H, Grinspoon SK. Fracture prevalence among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected versus non-HIV-infected patients in a large U.S. healthcare system. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2008;93:3499–3504. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong HV, Cortes YI, Shiau S, Yin MT. Osteoporosis and fractures in HIV/hepatitis C virus coinfection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2014;28:2119–2131. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolland MJ, Grey AB, Gamble GD, Reid IR. CLINICAL Review # : low body weight mediates the relationship between HIV infection and low bone mineral density: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;92:4522–4528. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnsten JH, Freeman R, Howard AA, Floris-Moore M, Lo Y, Klein RS. Decreased bone mineral density and increased fracture risk in aging men with or at risk for HIV infection. AIDS. 2007;21:617–623. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280148c05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin MT, Zhang CA, McMahon DJ, Ferris DC, Irani D, Colon I, et al. Higher rates of bone loss in postmenopausal HIV-infected women: a longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2012;97:554–562. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoy J. Bone, fracture and frailty. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:309–314. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283478741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallant JE, Staszewski S, Pozniak AL, DeJesus E, Suleiman JM, Miller MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir DF vs stavudine in combination therapy in antiretroviral-naive patients: a 3-year randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292:191–201. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stellbrink HJ, Orkin C, Arribas JR, Compston J, Gerstoft J, Van Wijngaerden E, et al. Comparison of changes in bone density and turnover with abacavir-lamivudine versus tenofovir-emtricitabine in HIV-infected adults: 48-week results from the ASSERT study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:963–972. doi: 10.1086/656417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McComsey GA, Kitch D, Daar ES, Tierney C, Jahed NC, Tebas P, et al. Bone mineral density and fractures in antiretroviral-naive persons randomized to receive abacavirlamivudine or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-emtricitabine along with efavirenz or atazanavirritonavir: AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5224s, a substudy of ACTG A5202. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1791–1801. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ofotokun I, McIntosh E, Weitzmann MN. HIV: inflammation and bone. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012;9:16–25. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0099-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant PM, Kitch D, McComsey GA, Dube MP, Haubrich R, Huang J, et al. Low baseline CD4+ count is associated with greater bone mineral density loss after antiretroviral therapy initiation. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1483–1488. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotter EJ, Malizia AP, Chew N, Powderly WG, Doran PP. HIV proteins regulate bone marker secretion and transcription factor activity in cultured human osteoblasts with consequent potential implications for osteoblast function and development. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:1521–1530. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibellini D, De Crignis E, Ponti C, Cimatti L, Borderi M, Tschon M, et al. HIV-1 triggers apoptosis in primary osteoblasts and HOBIT cells through TNFalpha activation. J Med Virol. 2008;80:1507–1514. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibellini D, Borderi M, De Crignis E, Cicola R, Vescini F, Caudarella R, et al. RANKL/OPG/TRAIL plasma levels and bone mass loss evaluation in antiretroviral naive HIV-1-positive men. J Med Virol. 2007;79:1446–1454. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vikulina T, Fan X, Yamaguchi M, Roser-Page S, Zayzafoon M, Guidot DM, et al. Alterations in the immuno-skeletal interface drive bone destruction in HIV-1 transgenic rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13848–13853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003020107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamen DL, Alele JD. Skeletal manifestations of systemic autoimmune diseases. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010;17:540–545. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328340533d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardy R, Cooper MS. Bone loss in inflammatory disorders. J Endocrinol. 2009;201:309–320. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hileman CO, Labbato DE, Storer NJ, Tangpricha V, McComsey GA. Is bone loss linked to chronic inflammation in antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected adults? A 48-week matched cohort study. AIDS. 2014;28:1759–1767. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Libois A, Clumeck N, Kabeya K, Gerard M, De Wit S, Poll B, et al. Risk factors of osteopenia in HIV-infected women: no role of antiretroviral therapy. Maturitas. 2010;65:51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown TT, Chen Y, Currier JS, Ribaudo HJ, Rothenberg J, Dube MP, et al. Body composition, soluble markers of inflammation, and bone mineral density in antiretroviral therapy-naive HIV-1-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:323–330. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318295eb1d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masyeni S, Utama S, Somia A, Widiana R, Merati TP. Factors influencing bone mineral density in ARV-naive patients at Sanglah Hospital, Bali. Acta Med Indones. 2013;45:175–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamill MM, Ward KA, Pettifor JM, Norris SA, Prentice A. Bone mass, body composition and vitamin D status of ARV-naive, urban, black South African women with HIV infection, stratified by CD(4) count. Osteoporosis Int. 2013;24:2855–2861. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2373-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grijsen ML, Vrouenraets SM, Steingrover R, Lips P, Reiss P, Wit FW, et al. High prevalence of reduced bone mineral density in primary HIV-1-infected men. AIDS. 2010;24:2233–2238. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833c93fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babiker AG, Emery S, Fatkenheuer G, Gordin FM, Grund B, Lundgren JD, et al. Considerations in the rationale, design and methods of the Strategic Timing of AntiRetroviral Treatment (START) study. Clin Trials. 2013;10:S5–S36. doi: 10.1177/1740774512440342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Y, Fuerst T, Hui S, Genant HK. Standardization of bone mineral density at femoral neck, trochanter and Ward's triangle. Osteoporosis Int. 2001;12:438–444. doi: 10.1007/s001980170087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hui SL, Gao S, Zhou XH, Johnston CC, Jr., Lu Y, Gluer CC, et al. Universal standardization of bone density measurements: a method with optimal properties for calibration among several instruments. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1463–1470. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.9.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Looker AC, Borrud LG, Hughes JP, Fan B, Shepherd JA, Melton LJ., 3rd Lumbar spine and proximal femur bone mineral density, bone mineral content, and bone area: United States, 2005-2008. Vital Health Stat. 2012;11:1–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schousboe JT, Shepherd JA, Bilezikian JP, Baim S. Executive summary of the 2013 International Society for Clinical Densitometry Position Development Conference on bone densitometry. J Clin Densitom. 2013;16:455–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, et al. Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporosis Int. 2014;25:2359–2381. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with application to linear models, logistic regression and survival analysis. Springer; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; USA: [2014 15th September 2014]. Available from: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-your-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiau S, Broun EC, Arpadi SM, Yin MT. Incident fractures in HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2013;27:1949–1957. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328361d241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cotter AG, Sabin CA, Simelane S, Macken A, Kavanagh E, Brady JJ, et al. Relative contribution of HIV infection, demographics and body mass index to bone mineral density. AIDS. 2014;28:2051–2060. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kooij KW, Wit FW, Bisschop PH, Schouten J, Stolte IG, Prins M, et al. Low bone mineral density in patients with well-suppressed HIV infection is largely explained by body weight, smoking and prior advanced HIV disease. J Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu499. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.