Abstract

Background

We sought to evaluate the utilization of blue dye in addition to radioisotope and its relative contribution to sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping at a high-volume institution.

Methods

Using a prospectively maintained database, 3,402 breast cancer patients undergoing SLN mapping between 2002 and 2006 were identified. Trends in utilization of blue dye and results of SLN mapping were assessed through retrospective review. Statistical analysis was performed with Student t test and chi-square analysis.

Results

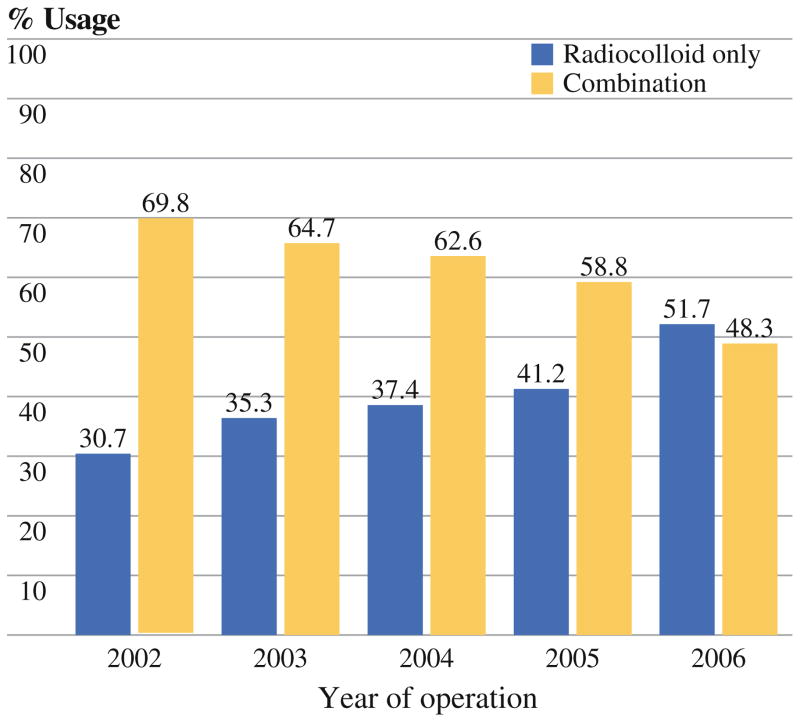

2,049 (60.2%) patients underwent mapping with dual technique, and 1,353 (39.8%) with radioisotope only. Blue dye use decreased gradually over time (69.8% in 2002 to 48.3% in 2006, p <0.0001). Blue dye was used significantly more frequently in patients with lower axillary counts, higher body mass index (BMI), African-American race, and higher T stage, and in patients not undergoing skin-sparing mastectomy. There was no difference in SLN identification rates between patients who had dual technique versus radiocolloid alone (both 98.4%). Four (0.8%) of 496 patients who had dual mapping and a positive SLN had a blue but not hot node as the only involved SLN. None of these four had significant counts detected in the axilla intraoperatively. Nine (0.4%) of 2,049 patients who had dual mapping had allergic reactions attributed to blue dye.

Conclusions

Blue dye use has decreased with increasing institutional experience with SLN mapping. In patients with adequate radioactive counts in the axilla, blue dye is unlikely to improve the success of sentinel node mapping.

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping is the preferred approach to axillary staging in clinically node-negative breast cancer patients. However, several technical aspects regarding sentinel node mapping remain controversial. One area of controversy is the ideal mapping agent(s). Multi-center studies suggested that dual mapping with isosulfan blue dye and radioisotope significantly decreases false-negative rates.1 However, use of blue dye has been associated with allergic reactions, including severe anaphylactic reactions requiring resuscitation.2 Thus, concerns about allergic reactions to blue dye have caused many surgeons to question its routine use in lymphatic mapping.

The SLN biopsy procedure in known to have a significant learning curve.3,4 It has been reported that, with increasing experience, success in localization with radioisotope steadily increases, with a decline in the marginal benefit offered by using blue dye.5 Therefore, we sought to evaluate the utilization of blue dye in addition to isotope and its relative contribution to SLN mapping at our institution. We found that blue dye use has decreased with increasing institutional experience with SLN mapping. Few patients had a blue only node as their only positive node, and all of those patients had poor radioisotope uptake in their axilla. Therefore, our data suggest that, in patients with adequate radioactive counts in the axilla, blue dye is unlikely to improve the success rate.

METHODS

Using a prospectively maintained database, we identified 3,402 clinically node-negative breast cancer patients who underwent lymphatic mapping with radiocolloid guidance between 2002 and 2006. Techniques of mapping and prophylaxis against allergic reaction to blue dye with histamine (H1 and H2) blockers and steroids are described elsewhere.6,7 Lymphatic mapping was performed with technetium Tc99 m-labeled sulfur colloid, at dose of 2.5 mCi for patients scheduled for operation the following day and 0.5 mCi for patients having same-day surgery. Lymphoscintigraphy (LSG) with anterior and lateral views was performed beginning at 20 min and up to 4 h after radiocolloid injection in selected patients. Intraoperative lymphatic mapping was performed with radiocolloid, with or without 1% isosulfan blue dye at the discretion of the operating surgeon. Three to five milliliters of blue dye was injected 5–10 min before SLN biopsy. Lymph nodes recovered from the axilla were considered SLNs if they had higher radioactivity than background counts and/or were blue stained. All SLNs were sliced at 2- to 3-mm intervals and entirely submitted for histopathologic study. Tissue blocks were serially sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis for cytokeratin was performed if the nodes were negative based on staining with hematoxylin and eosin. The SLN identification rate was defined as the percentage of patients whose SLN was identified at operation.

Data collected from retrospective chart review included patient demographics, tumor characteristics, lymphoscintigraphic drainage patterns, surgery type including technique of SLN mapping, and intraoperative and pathologic findings.

Stata SE version 10.0 statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) was used for statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using cross-tabulation with chi-square analysis or Student t test. Differences were considered statistically significant when p <0.05. This study was approved by the institutional review board.

RESULTS

Two thousand forty-nine patients underwent mapping with dual technique, and 1,353 patients underwent mapping with radiocolloid only. Blue dye use decreased gradually over time (69.8% in 2002 to 48.3% in 2006, p <0.0001; Fig. 1). Blue dye was used significantly more frequently in patients with higher BMI, African-American race, and higher T stage (Table 1). Use of blue dye also varied by surgery performed.

FIG. 1.

Trends in lymphatic mapping technique: combination versus radiocolloid alone

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Radiocolloid N = 1,353 (%) |

Combination N = 2,049 (%) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.0002 | ||

| Mean | 55.3 | 56.8 | |

| Median (range) | 54 (22–99) | 56 (23–91) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <0.0001* | ||

| Mean | 26.8 | 28.2 | |

| Median (range) | 26 (16–52) | 27 (14–64) | |

| Race | <0.0001 | ||

| White | 1,056 (78.1) | 1,525 (71.8) | |

| African-American | 228 (16.9) | 480 (22.6) | |

| Others | 68 (5.0) | 119 (5.6) | |

| Surgery type | <0.0001 | ||

| Breast-conserving surgery | 657 (48.6) | 1,158 (56.5) | |

| Total mastectomy | 378 (27.9) | 792 (38.7) | |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy | 318 (23.5) | 99 (4.8) | |

| T stage | <0.0001 | ||

| Tis | 269 (19.9) | 269 (13.1) | |

| T1 | 794 (58.7) | 1,219 (59.5) | |

| T2 | 261 (19.3) | 490 (23.9) | |

| T3 | 25 (1.8) | 51 (2.5) | |

| T4 | 4 (0.3) | 20 (1.0) | |

| Histology | 0.41 | ||

| IDC/DCIS | 1,137 (84.0) | 1,683 (82.1) | |

| ILC | 90 (6.7) | 147 (7.2) | |

| Mixed ductal and lobular | 88 (6.5) | 143 (7.0) | |

| Other | 38 (2.8) | 76 (3.7) | |

| Neoadjuvant treatment (chemo/hormonal) | 0.22 | ||

| No | 1,179 (87.1) | 1,755 (85.7) | |

| Yes | 174 (12.9) | 294 (14.3) |

IDC invasive ductal carcinoma, DCIS ductal carcinoma in situ, ILC invasive lobular carcinoma

Rank-sum test

There was no difference in SLN identification rate between patients who had dual technique versus radiocolloid alone (both 98.4%, Table 2). Patients with dual mapping had fewer SLNs removed (mean 2.7 vs. 2.9, p = 0.03). Patients who received blue dye were significantly more likely to have undergone preoperative LSG. Of those who underwent LSG, patients who had no lymphatic drainage identified were more likely to have blue dye used. Additionally, patients receiving blue dye were more likely to not have SLNs localized (i.e., detectable) transcutaneously at the beginning of surgery and had lower pre-excision axillary counts. On multivariate analysis to determine patient-related factors associated with blue dye use (Table 3), higher BMI, African-American race, T2 or greater stage, not undergoing skin-sparing mastectomy, and not having preoperative transcutaneous localization of sentinel nodes were independently associated with blue dye use.

TABLE 2.

Sentinel lymph node characteristics

| Characteristics | Radiocolloid N = 1,353 (%) |

Combination N = 2,049 (%) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLN identified | 0.8 | ||

| Yes | 1,331 (98.4) | 2,017 (98.4) | |

| No | 22 (1.6) | 32 (1.6) | |

| No. of SLN found | 0.03 | ||

| Mean | 2.9 | 2.7 | |

| Median (range) | 3 (0–13) | 2 (0–12) | |

| Positive SLNa | 0.55 | ||

| Yes | 254 (19.1) | 402 (19.9) | |

| No | 1,077 (80.9) | 1,615 (80.1) | |

| LSG performed? | <0.0001 | ||

| Yes | 858 (63.4) | 1,720 (83.9) | |

| No | 495 (36.6) | 329 (16.1) | |

| If LSG performed, axillary drainage seen? | <0.0001 | ||

| Yes | 833 (97.1) | 1,566 (91.1) | |

| No | 25 (2.9) | 154 (8.9) | |

| Preoperative transcutaneous localization | <0.0001 | ||

| Yes | 1,267 (97.1) | 1,759 (91.5) | |

| No | 38 (2.9) | 164 (8.5) | |

| Pre-excision axillary countsb | <0.0001* | ||

| Mean | 134.1 | 82.4 |

Rank-sum test

Defined here as any lymph node involvement, including isolated tumor cells

Limited to patients who had measurements obtained with a gamma probe collimator

TABLE 3.

Multivariate analysis of determinants of blue dye use

| Characteristics | OR | p Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| <25 | ||||

| ≥25 | 1.23 | 0.01 | 1.05 | 1.44 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Referent | |||

| African-American | 1.34 | 0.002 | 1.11 | 1.62 |

| Others | 1.12 | 0.54 | 0.78 | 1.62 |

| Surgery type | ||||

| Breast-conserving surgery | Referent | |||

| Total mastectomy | 1.14 | 0.11 | 0.97 | 1.35 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy | 0.17 | <0.0001 | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| Clinical T stage | ||||

| Tis | Referent | |||

| T1 | 1.09 | 0.43 | 0.87 | 1.38 |

| T2 or higher | 1.35 | 0.02 | 1.05 | 1.73 |

| Preoperative transcutaneously localized SLN | ||||

| Yes | Referent | |||

| No | 3.23 | <0.0001 | 2.21 | 4.72 |

When patients who underwent LSG were analyzed separately, higher BMI, African-American race, T2 or greater stage, not undergoing skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM), and not having preoperative transcutaneous localization of sentinel nodes remained independently associated with blue dye use on univariate and multivariate analysis. Not having drainage on LSG also was an independent predictor of blue dye use [no drainage vs. drainage: odds ratio (OR) 2.5; confidence interval (CI) 1.5–4.2, p <0.0001]. In patients who did not undergo LSG, the only independent variables associated with blue dye use was not undergoing skin-sparing mastectomy (non-SSM vs. SSM, OR 0.15, CI 0.11–0.2, p <0.0001) and not having preoperative transcutaneous localization of sentinel nodes (no localization vs. yes, OR 3.3, CI 2.2–4.8, p = 0.007). In patients who had dual mapping, blue and hot nodes were more likely to be involved than nodes that were only hot or only blue (51.8 vs. 23.8 vs. 36.9%, p <0.0001; Table 4). Of the 496 patients who had dual-agent mapping, 69 patients (13.9%) had a hot but not blue node as their only positive node. Only 4 (0.8%) of 496 patients who had dual mapping and a positive SLN had a blue but not hot node as the only involved SLN. One patient (patient 1 in Table 5) had tumor cells detected on touch preparation but not detected on H&E and IHC. However, based on the intraoperative touch preparation analysis, the patient underwent completion axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) and was found to have one non-sentinel node with a 0.4-mm micrometastasis and was treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Two of the four patients had macrometastases in the blue node; both underwent ALND and received chemotherapy; one had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. One patient had isolated tumor cells only; the patient did not undergo ALND; she received endocrine therapy only for this estrogen-receptor-positive T1bN(i+) cancer.

TABLE 4.

Likelihood of sentinel node metastatic involvement based on blue dye and isotope uptake: analysis of the 1,484 sentinel nodes removed from 496 patients who underwent dual-agent mapping and had a positive SLN

| No. of SLN N = 1,484 (%) |

No. of positive SLN N = 620 (%) |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue only | 65 (4.4) | 24 (3.9) | <0.0001 |

| Hot only | 492 (33.1) | 117 (18.9) | |

| Blue and hot | 927 (62.5) | 479 (77.3) |

Positive SLN included any SLN that was positive by routine H&E or IHC staining to include those with isolated tumor cells [pN0(i+)]

TABLE 5.

Characteristics of blue only SLN-positive cases

| ID | No. of SLN (order of retrieval/total no.) | Sentinel node burden (ITC, micro, macro) | LSG

|

Tc injection location | Blue dye injection location | Sentinel node count (ex vivo)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axillary drain | Time to drainage | Blue node | Additional node counts | Primary tumor count | |||||

| 1 | 1/1 | Touch preparation onlya | Yes | 4 h, moderate signal | Unknown | Peritumoral | 0 | NA | 2,791 |

| 2 | 1/1 | Macro | No | NA | Peritumoral | Peritumoral | 0 | NA | Unknown |

| 3 | 1/2 | Macro | Yes | 5 h, faint | Peritumoral | Peritumoral | 0 | 0/0 | 1,481 |

| 4 | 3/5 | ITCb | No | NA | Peritumoral | Peritumoral | 9 | 3, 0, 5, 5 | 2,400 |

NA not applicable

Involvement on touch preparation only, not on H&E or IHC

Cluster of two malignant cells detected only by cytokeratin IHC

All four patients who had blue only nodes as their only positive SLN had preoperative LSG; two showed no drainage, and two showed drainage at 4–5 h. None of the four had significant counts detected in the axilla intraoperatively. In two of the patients, the blue node that contained metastasis was the only removed node. In the third patient, one additional nonradioactive node was removed, and in the fourth patient, four additional nodes were removed, all with very low radioactivity (ex vivo counts of 0–5, compared with counts of 2,500 over the primary tumor).

Nine (0.4%) of 2,049 patients who had dual mapping had allergic reactions attributed to blue dye. Two patients experienced hives only, and two had hives and periorbital edema. Five patients had hypotension, two requiring pressor support and intensive care unit admission. Both patients who had anaphylactic reaction had received prophylactic histamine blockers and steroids prior to injection of the blue dye.

DISCUSSION

Although sentinel node mapping has become widely accepted for axillary staging in clinically node-negative breast cancer patients, technical aspects regarding sentinel node mapping remain controversial. This study evaluated utilization of blue dye in addition to radiocolloid and its relative contribution to SLN mapping at our institution. We found that blue dye use has decreased with increasing institutional experience with SLN mapping. Only 0.8% of patients who had dual mapping had a blue only node as their only positive node, and all of those patients had poor radioisotope uptake in their axilla. Therefore, our data suggest that, in patients with adequate isotope uptake in the axilla, blue dye is unlikely to improve the success rate.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer using the combination of radiocolloid and blue dye was first reported by Albertini and colleagues in 1996.8 Albertini et al. reported a higher SLN identification rate with dual mapping than had been previously reported with blue dye only by Giuliano et al., and with radiocolloid only by Krag et al.9,10 In a multi-institutional study reported by McMasters et al., the impact of mapping agent on identification and false-negative rates was assessed.1 Eight hundred six patients were enrolled by 99 surgeons, and SLN biopsy was performed by single-agent (blue dye alone or radiocolloid alone) or dual-agent injection at the discretion of the operating surgeon. All patients underwent completion level I/II axillary lymph node dissection. The SLN identification rate was slightly higher in the dual-agent injection group, although this difference was not statistically significant. The mean number of SLNs removed was greater in the dual-agent injection group (1.5 vs. 2.1; p <0.0001). The false-negative rate was significantly greater for patients who underwent single-agent versus dual-agent injection (11.8 vs. 5.8%; p <0.05). The false-negative rates were 12.3 and 9.1% for patients undergoing blue dye injection alone or radioactive colloid injection alone, respectively. The relative benefit of blue dye was also evaluated in the validation phase of the ALMANAC trial.11 All patients underwent dual-agent mapping and then ALND. Evaluating the distribution of positive sentinel nodes among those identified by dye alone, isotope alone, and by the combination, it was reported that, had radiocolloid only been used, the identification rate would have dropped by 10% and the false-negative rate would have increased by 4.3%.

Degnim and colleagues at the University of Michigan investigated whether blue dye provides benefit in patients with drainage seen on LSG.12 In five of 380 cases with positive LSG the sentinel nodes obtained were blue but not hot, for a 1.3% marginal benefit of dye in the technical success of the procedure. Sentinel nodes positive for metastasis were found in 102 of 380 cases; in 3 cases, the only positive SLN was blue but not hot. The authors therefore concluded that omission of blue dye would have increased the false-negative rate of the sentinel node procedure by approximately 2.5%. Cody et al. examined factors contributing to the success of sentinel node mapping using blue dye and radiotracer individually or in combination among 1,000 consecutive patients undergoing SLN mapping at Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC).13 The variables associated with successful SLN localization by blue dye or isotope were found to overlap but were not identical. It was thus proposed that dye and isotope complement each other and that SLN biopsy for breast cancer should use both. However, in a subsequent study from MSKCC, Derossis et al. reported the institutional learning curve for the first 2,000 SLN biopsy procedures at their institution.5 Comparing the first 500 with the latter 500 cases, success in identifying the SLN by blue dye did not improve with experience, although success in isotope localization steadily increased, from 86 to 94% (p < 0.00005). With the increasing success of isotope mapping, the marginal benefit of blue dye, described as the proportion of cases in which the SLN was identified by blue dye alone, steadily declined, from 9 to 3% (p = 0.0001). The proportion of positive SLNs identified by blue dye did not change with experience, but isotope success steadily increased, from 88 to 98% (p = 0.0015). The proportion of positive SLNs identified by blue dye alone declined from 12 to 2% (p = 0.0015). Our results are consistent with these reported from MSKCC. We found no difference in identification rate with radiocolloid only versus dual mapping, potentially reflecting the fact that blue dye was not used when there were high axillary counts at the initiation of the case. With increasing institutional experience, there has been an increase in mapping with radiocolloid alone. Importantly, in our series, only 4 (0.8%) of 496 patients who had dual mapping and a positive SLN had a blue but not hot node as the only involved SLN. This suggests an even lower marginal benefit for blue dye in our series then in that reported from MSKCC. The current study was conducted in an era when we had abandoned routine completion lymph node dissection, therefore we are unable to report false-negative rates observed with dual-agent versus radiocolloid only mapping approaches. However, it is notable that all four patients who had blue only positive nodes had low axillary counts intraoperatively. This supports the use of blue dye selectively and suggests that, if blue dye is avoided in patients with adequate radiocolloid uptake in the axilla, there is unlikely to be a significant decrease in the success rate.

Single-institution studies with isosulfan blue use have reported allergic reaction rates of 0.7–1.9%.2,14–16 Most reactions are urticaria and hives, with hypotension being reported in 0.5% of patients.14 Other agents such as methylene blue are used as an alternative to isosulfan blue dye; however, these agents also have side-effects.17,18 In 2001 our group started routinely administering histamine blockers and steroids prior to blue dye administration.7 This has reduced the severity but not the incidence of allergic reactions. The finding that 9 (0.4%) of 2,049 patients who had dual mapping had allergic reactions attributed to blue dye, while only 4 (0.2%) of the 2,049 patients had a blue only positive node, emphasizes the importance of weighing the benefit of blue dye use in each procedure, especially when there is adequate radionucleotide uptake in the axilla, and patient comorbidities.

In our institutional practice, many surgeons still use blue dye due to its technical advantages. Blue dye facilitates identification of sentinel nodes; thus, use of blue dye allows for training residents and fellows in both techniques. Blue dye use may also speed up the sentinel node mapping procedure. In patients who had dual-agent mapping and positive sentinel nodes, the nodes that were hot and blue were significantly more likely to be involved with metastatic disease compared with nodes that took up one tracer only. Thus, dual mapping may direct the surgeon to the nodes most likely to be involved first. Blue dye use was also associated with removal of fewer nodes.

Due to its retrospective nature, our study has several limitations. First, we were unable to determine the reasons individual surgeons omitted blue dye in selected cases. We were unable to assess the impact of blue dye use on the operative time to complete lymphatic mapping. We were unable to determine the effect of blue dye on the false-negative rates, as patients did not undergo planned completion axillary lymph node dissection. We also do not have enough follow-up to assess the effect of mapping technique on regional recurrence rates.

In conclusion, blue dye use has decreased with increasing institutional experience with SLN mapping. Blue dye use varies with respect to patient and tumor characteristics as well as type of surgery. Nodes that are both blue and hot are more likely to be involved, thus blue dye may assist in identifying first-echelon nodes. However, in patients with adequate isotope uptake in the axilla, blue dye is unlikely to improve the identification rate. Thus, in experienced hands, use of blue dye can be individualized, weighing the relative benefit of blue dye against potential risks.

Acknowledgments

We thank Judy Roehm for assistance with manuscript preparation

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST None.

References

- 1.McMasters KM, Tuttle TM, Carlson DJ, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer: a suitable alternative to routine axillary dissection in multi-institutional practice when optimal technique is used. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2560–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.13.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albo D, Wayne JD, Hunt KK, et al. Anaphylactic reactions to isosulfan blue dye during sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2001;182:393–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00734-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke D, Newcombe RG, Mansel RE. The learning curve in sentinel node biopsy: the ALMANAC experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:211S–5S. doi: 10.1007/BF02523631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cody HS, III, Hill AD, Tran KN, Brennan MF, Borgen PI. Credentialing for breast lymphatic mapping: how many cases are enough? Ann Surg. 1999;229:723–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199905000-00015. discussion 6–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derossis AM, Fey J, Yeung H, et al. A trend analysis of the relative value of blue dye and isotope localization in 2,000 consecutive cases of sentinel node biopsy for breast cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:473–8. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raut CP, Daley MD, Hunt KK, et al. Anaphylactoid reactions to isosulfan blue dye during breast cancer lymphatic mapping in patients given preoperative prophylaxis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:567–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.99.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raut CP, Hunt KK, Akins JS, et al. Incidence of anaphylactoid reactions to isosulfan blue dye during breast carcinoma lymphatic mapping in patients treated with preoperative prophylaxis: results of a surgical prospective clinical practice protocol. Cancer. 2005;104:692–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albertini JJ, Lyman GH, Cox C, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in the patient with breast cancer. JAMA. 1996;276:1818–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giuliano AE, Kirgan DM, Guenther JM, Morton DL. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1994;220:391–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199409000-00015. discussion 398–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krag DN, Weaver DL, Alex JC, Fairbank JT. Surgical resection and radiolocalization of the sentinel lymph node in breast cancer using a gamma probe. Surg Oncol. 1993;2:335–9. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(93)90064-6. discussion 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goyal A, Douglas-Jones A, Monypenny I, Sweetland H, Stevens G, Mansel RE. Is there a role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in ductal carcinoma in situ? Analysis of 587 cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;98:311–4. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Degnim AC, Oh K, Cimmino VM, et al. Is blue dye indicated for sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer patients with a positive lymphoscintigram? Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:712–7. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cody HS, III, Klauber-Demore N, Borgen PI, Van Zee KJ. Is it really duct carcinoma in situ? Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:617–9. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montgomery LL, Thorne AC, Van Zee KJ, et al. Isosulfan blue dye reactions during sentinel lymph node mapping for breast cancer. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:385–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200208000-00026. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leong SP, Donegan E, Heffernon W, Dean S, Katz JA. Adverse reactions to isosulfan blue during selective sentinel lymph node dissection in melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:361–6. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cimmino VM, Brown AC, Szocik JF, et al. Allergic reactions to isosulfan blue during sentinel node biopsy—a common event. Surgery. 2001;130:439–42. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simmons RM. Freezing breast cancers to enhance complete resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:999. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.09.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masannat Y, Shenoy H, Speirs V, Hanby A, Horgan K. Properties and characteristics of the dyes injected to assist axillary sentinel node localization in breast surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:381–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]