Abstract

This study modeled children's trajectories of teacher rated aggressive-disruptive behavior problems assessed at six time points between the ages of 6 and 11 and explored the likelihood of being exposed to DSM-IV qualifying traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in 837 urban first graders (71% African American) followed-up for 15 years. Childhood trajectories of chronic high or increasing aggressive-disruptive behavior distinguished males more likely to be exposed to an assaultive violence event as compared to males with a constant course of low behavior problems (ORchronic high = 2.8, 95% CI = 1.3, 6.1 and ORincreasing = 4.5, 95% CI = 2.3, 9.1, respectively). Among females, exposure to traumatic events and vulnerability to PTSD did not vary by behavioral trajectory. The findings illustrate that repeated assessments of disruptive classroom behavior during early school years identifies more fully males at increased risk for PTSD-level traumatic events, than a single measure at school entry does.

Keywords: growth trajectories, childhood antecedents, child development, traumatic events, PTSD

Introduction

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a syndrome of three symptom clusters, re-experiencing, avoidance and numbing, and hyper-arousal, caused by an exposure to a traumatic event. According to DSM-IV, the disturbance must last at least one month and cause clinically significant distress or impairment. A majority of adults are exposed to traumatic events at some point in their lives, however, only an estimated 5–10% develop PTSD [6, 17, 23, 36]. A sex-related pattern consistently found in PTSD studies indicates that (1) males are more likely to experience traumatic events, in particular, events that involve assaultive violence, serious accidents, and witnessing violence and (2) females have a higher probability to develop PTSD following trauma [48].

Additional efforts are needed to identify those susceptible to the disorder as early as possible in order to develop efficient and effective prevention approaches [30]. In the U.S., over one out of every two individuals has experienced a traumatic event involving victimization or witnessing violence by young adulthood [6, 10]. In general, differences in the overall occurrence of lifetime trauma reported by youth in high-crime urban environments vary little from those experienced in nonurban areas. However, substantial differences between residents of urban vs. nonurban areas have been reported in the severity or types of traumatic events [6]. The likelihood of certain types of events of greater severity occurring in urban inner city areas may in part account for higher conditional probabilities for PTSD among disadvantaged ethnic minorities [24, 31]. Conduct problems or preexisting externalizing problems have been associated with exposure of traumatic events [12, 20, 27] and the conditional probability of PTSD [3, 16, 24, 26, 27]. However, research on childhood risk factors for trauma exposure and PTSD has relied largely on retrospective data. In this report, we seek to gain a better understanding of the risk for exposure and PTSD conferred by early conduct problems assessed during the early school years. Teacher rated behavior problems at entry into primary school (approximately age six) have been linked with the likelihood of subsequent exposure to traumatic events in two U.S. longitudinal studies [8, 46]. In one of the studies, behavior problems also increased the likelihood of PTSD following exposure [8]. Teacher rated antisocial and hyperactivity behavior averaged over the ages of 5–11 has also been found to be associated with increased risk of trauma exposure and adverse responses to traumatic events in a cohort of New Zealand young adults [27]. However, early childhood aggressive-disruptive behavior is not stable [2] and can be modified by familial and school influences [21, 29]. Thus relying on an average or an assessment assessed at a single time point may not be a reliable predictor to classify children at risk for suspected outcomes in adolescence and young adulthood [37–39]. While children with fairly stable behavioral trajectories throughout the early school years will be correctly identified by a cross sectional snapshot at any age, youth with changing behavior patterns, will have a higher probability of being misclassified if assessed only once. Thus, the pattern or behavior trajectory derived from multiple assessments overtime might improve the identification of children at high risk for exposure to trauma and PTSD.

For this report, we use gender specific early problem behavior trajectories identified from teacher reports of aggressive-disruptive behavior spanning from ages 6–11 gathered on an urban cohort subsequently followed for 15 years. Previous work on this cohort has identified three aggressive behavior patterns that differed in severity among females, a stable high, a stable moderate and a stable low aggressive trajectory pattern; whereas among males, an increasing aggressive trajectory was identified, in addition to a stable low and stable high trajectory pattern [37, 38, 41]. The behavioral trajectories have been found to differ significantly on several adolescent and adult outcomes, including self reported antisocial behaviors and official court adjudication records [40], providing construct validity for the trajectory classes. Using a similar approach, we examine the link between the various aggressive-disruptive trajectories and the cumulative prevalence of exposure to traumatic events through young adulthood. Among both males and females, we expect a stable trajectory pattern of high aggressive behavior between the ages of 6–11 to be associated with an increased exposure to traumatic events, especially those involving assaultive violence. An additional hypothesis that we examine only among males is that a trajectory of increasing aggressive behavior in early childhood (low at age 6 but became high in subsequent years) might be associated with increased exposure to traumatic events, especially those involving assaultive violence and predict an increased risk for PTSD. The optimal prevention of PTSD is the reduction of a persons' risk of exposure to traumatic events, as a subset of the population with greater risks for exposure to traumatic events have a higher probability of the occurrence of PTSD. Thus, evidence that early development of disruptive/aggressive behavior increases the risk for subsequent exposure to traumatic events (especially those involving violence, which carry a higher risk of PTSD) has important implications for the prevention of the disorder.

Methods

Participants

Data are from a prospective study conducted within the context of a 2 year group randomized prevention trial targeting early learning and aggression [18, 22, 47]. During two successive school years (1985 and 1986), a total of 2,311 youths entered 43 first grade classrooms in 19 primary schools within a single public school system of a mid-Atlantic city in the USA. Schools were selected from five different urban areas that varied by ethnic composition, type of housing, income, and other US Census characteristics; three or four schools were selected within each area. All students on the first grade rosters were recruited and participation rates in the prevention trial were very high (92%). This study focuses on the 1,339 students randomly assigned to the control classrooms within the evaluation design to allow us to model the natural behavioral trajectories without any intervention influences [22]. At entrance into first grade, the average age was six years (girls: M = 6.2, SD = 0.4; boys: M = 6.3, SD = 0.5) and the majority of the students were African–American (see Table 1). Fifteen years later, nearly 75% of the surviving controls participated in personal interviews that included an assessment of lifetime traumatic experiences and PTSD (four females and 15 males were confirmed dead by a National Death Index search and/or an immediate family member).

Table 1. Gender specific sample characteristics at baseline and of those included in the analytic sample of the general growth mixture modeling (GGMM).

| Baseline (n = 1,339) | GGMM analytic sample (n = 837) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Males (n = 675) | Females (n = 664) | Males (n = 402) | Females (n = 435) | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-minority | 262 | 39 | 206 | 31 | 129 | 32 | 111 | 26 |

| Minority | 413 | 61 | 458 | 69 | 273 | 68 | 324 | 74 |

| Free lunch in first grade | ||||||||

| Paid | 331 | 49 | 328 | 49 | 182 | 45 | 195 | 45 |

| Subsidized or free | 341 | 50 | 329 | 50 | 220 | 55 | 240 | 55 |

| Missing | 3 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Peer rejectiona | ||||||||

| Almost never | 310 | 46 | 361 | 54 | 211 | 52 | 257 | 59 |

| Rarely | 182 | 27 | 151 | 23 | 126 | 31 | 124 | 28 |

| Sometimes | 70 | 10 | 48 | 7 | 43 | 11 | 38 | 9 |

| Often/always | 35 | 5 | 24 | 4 | 22 | 4 | 16 | 4 |

| Missing | 78 | 12 | 80 | 12 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Mean | 95% confidence interval | Mean | 95% confidence interval | Mean | 95% confidence interval | Mean | 95% confidence interval | |

|

| ||||||||

| Aggressive-disruptive problem behavior scorea | 2.0 | 1.9–2.1 | 1.7 | 1.6–1.8 | 2.0 | 1.9–2.1 | 1.7 | 1.6–1.8 |

| Concentration problem scorea | 3.2 | 3.1–3.3 | 2.9 | 2.8–3.0 | 3.1 | 3.0–3.2 | 2.8 | 2.7–3.0 |

| Reading readiness scoreb | 27 | 26.2–26.8 | 27 | 26.8–27.4 | 27 | 26.2–27.0 | 27 | 26.6–27.4 |

Data were obtained from the Johns Hopkins Prevention Research Center cohort, originally recruited from 19 schools in a Mid-Atlantic school system at entry into first grade in 1985–1986 (age 6) and reassessed as young adults in 2000–2002. The analytic sample included all those with complete baseline information who were successfully assessed in young adulthood (mean age 21)

Based on teacher rated report assessed in fall of first grade

Standardized reading level based on California Achievement Test Form E&F in first grade, e.g. students at 27th percentile of national average

A small proportion of the controls did not have a fall of first grade teacher rating of behavior (80 females and 78 males) or had additional baseline covariate information missing (n = 44) and were consequently not included in our models, leaving us with an analytic sample size of 837 (62% of all the controls). The characteristics of these 837 individuals were similar to the entire sample of controls at baseline. However, attrition was slightly greater among males and Whites (see Table 1). Study protocols were approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Johns Hopkins University and Michigan State University's IRB also approved data analysis activities. Parental signed consent and child assent were obtained for the childhood assessments, followed by signed consent from each participant after age 18.

Assessment design

Data for this study were gathered in the fall and spring of first grade, the spring of second to fifth grades, and at the young adult follow-up assessment when participants were 20–23 years of age (mean age = 21 years, SD = 1.0). Central computerized school data sources provided data on free lunch eligibility, race, and standardized reading readiness scores assessed at the beginning of primary school. First grade assessments included teacher reports of child behaviors and peer rejection. Peer rejection and neuropsychological deficits such as attention problems have been found to be higher among youth with high levels of aggressive behavior [32]. Then for four more subsequent years (grades 2–5), teachers reported on the aggressive-disruptive behavior for each child. In early adulthood, exposure to traumatic events and PTSD were assessed as part of a 90-min standardized interview administered by experienced lay interviewers without special clinical training or credentials [7].

Measures

Childhood behavior

Teachers were guided through the Teacher Observation of Classroom Adaptation-Revised (TOCA-R), a structured interview of 36 items pertaining to a child's adaptation to classroom task demands over the preceding 3-week period by a trained assessor [50]. A child specific rating for each item was obtained using a six-point frequency scale (1 = “almost never” to 6 = “almost always”). The subscales for two domains, aggressive-disruptive behaviors and attention-concentration problems, were used for these analyses. Subscale scores ranged from 1 to 6 and were derived by summing the responses and dividing by the number of items. A higher score reflects more problematic behavior. Aggressive-disruptive behavior was assessed by the following 10 items: breaks rules, harms others and property, breaks things, takes others property, starts fights, lies, trouble accepting authority, yells at others, stubborn, and teases classmates. On average, girls scored 0.26 of a standard deviation lower than boys in this sample across time. Data from the six assessments occurring in primary school were used to model the growth in aggressive-disruptive behaviors: the first teacher rating was assessed shortly after entry into first grade and then for the next 5 years teacher ratings were obtained in the spring. Attention-concentration was assessed by the following 8 items: unable to or does not complete assignments, concentrate, work well alone, pay attention, learn up to ability work hard, stay on task, is not eager to learn, and poor effort. In terms of concurrent validity, each single unit of increase in teacher rated attention-concentration problems was associated with a two-fold increase in risk of teacher perception for the need for medication for such problems. The test-retest correlations over a 4-month interval and across different interviewers were above 0.6 and internal consistency reliabilities (Cronbach alpha) exceed 0.8; the aggressive-disruptive subscale ranged from 0.92 to 0.94 over grades 1–5.

First grade teachers also rated peer rejection based on a single item “rejected by classmates,” on a frequency scale covering total acceptance to total rejection. This item has been found to correlate significantly with peer nominations (not reported in this study) for the questions “which kids don't you like?” (Pearson r = 0.43) and “which kids are your best friends?” (r = −0.58).

Reading achievement

Standardized reading readiness scores assessed at the beginning of primary school were based on the California Achievement Test (CAT, Forms E & F)[49]. The CAT, one of the most frequently used standardized achievement batteries, was standardized on a nationally representative sample of 300,000 children. The internal consistency coefficient for the reading subscale exceeded 0.90. Alternate form reliability coefficients exceed 0.80 [49].

Family environment

Given the role of economic deprivation in youth involvement in antisocial behavior and the fact that in urban environments African–American youth are more likely than European–American youth to experience poverty [19], we also controlled for the effects of race (minority vs. nonminority as reference) and free lunch status in first grade (a proxy variable for family poverty). Free lunch eligibility has been foundtocorrelate highly with family income and other traditional measures of socioeconomic status [13].

Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

As part of the young adulthood follow-up, the history of lifetime exposure to 18 types of DSM-IV qualifying traumatic events was assessed. The traumatic events included: serious car accident; other serious accident; natural disaster; life-threatening illness; child's life-threatening illness; witnessed killing/serious injury; discovering a dead body; learning of a close friend/relative who was attacked, raped, sexually assaulted, in a serious car accident or other serious accidents; learning of sudden unexpected death of a close friend/relative; and six other events that were also categorized as being a victim of assaultive violence. The assaultive violence events included: rape, badly beaten up, held captive/tortured/kidnapped, shot/stabbed, mugged/threatened with a weapon, and sexual assault other than rape.

Respondents were asked to identify the most upsetting traumatic event (the worst event) they had experienced from the complete list of traumatic events they reported. PTSD was evaluated in connection with the worst event, using the PTSD section of the World Health Organization composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI), Version 2.1 [51], which is modeled after the National Institute of Mental Health-Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) [40]. Large scale epidemiologic studies generally employ the worst event method, which is an efficient alternative to assessing PTSD for all traumatic events [5, 9, 24]. It greatly reduces respondent burden and it focuses the attention to the event most likely to cause symptoms. When PTSD is assessed for multiple traumatic events, only a few additional cases are identified who do not develop PTSD following the worst event [4]. A validation study has found good agreement between the standardized interview and independent clinical re-interviews [7].

Statistical methodology

General growth mixture modeling (GGMM) was used to estimate growth parameters (i.e., intercept, slope, quadratic slope) associated with latent variables (growth factors) manifested by repeated measures of teacher-rated classroom aggressive-disruptive behavior over time separately for each gender [33, 35]. GGMM attempts to capture sample heterogeneity by representing the population distribution by two or more distinct “classes” of developmental trajectories with random variability around the mean trajectories within each class while simultaneously regressing the identified classes on the outcomes of exposure and PTSD. The Mplus Version 4.1 statistical software package [34] uses a full information maximum likelihood estimation under the assumption that the data are missing at random [1, 28], which is a widely accepted way of handling missing data [35, 42]. Parameter estimates were based on all available time points for a given case; 75% of the participants had at least four of the six assessment time points from first to fifth grade. Time was treated as a fixed parameter in the models and time points were fixed incrementally based on the spacing between assessment sessions (e.g., fall first grade fixed at zero, spring first grade fixed at 0.5, spring second grade fixed at 1.5, etc.). Bayesian Information Criterion, BIC [44], was used to select the best model.

We present odds ratio estimates from models that do not include any covariate influences on the class trajectories as well as estimates from models where covariates were included. Details of the modeling strategy that had already identified three sex specific classes and their association with antisocial outcomes in this cohort, including model fit indices and defining characteristics of the different trajectories are reported elsewhere [41]. Below we briefly highlight some of the important aspects of the modeling strategy. To avoid an over-specified model and non-identification, we constrained the effects of covariates on growth parameters to be the same across classes because covariances between intercept/slope, intercept/quadratic slope, and slope/quadratic slope factors were not statistically different from zero. We did not assume that the starting point of the aggressive-disruptive trajectory would affect development over time and did not control for any associations between the starting point and course over time.

In all models, standard errors were adjusted to account for the clustered sampling design (i.e., students within classrooms within schools). Furthermore, all analyses used automated multiple starting values [10 initial] in the optimization to reduce the risk that solutions represent local rather than global optima. Even though others have reported that PTSD before age 11 is rare [11, 15], we took into account the possibility that early experiences could alter the behavior trajectory. The behavior trajectories and regression estimates did not change appreciably when individuals with traumatic events occurring before or during the timeframe used to model the behavior trajectory pattern were excluded (78 males and 84 females). To help stabilize the estimates which become an issue when subgrouping on many variables we chose to present the findings including these individuals.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The vast majority (83%) of the sample had experienced at least one traumatic event by the time we interviewed them in their early 20s, and 9% of those exposed met criteria for lifetime PTSD. An estimated 47% had experienced at least one assaultive violence event. A greater proportion of males experienced a traumatic event than females, with only 12% of the males indicating they had not experienced any of the events listed as compared to 22% of the females. Males also were more likely than females to experience an assaultive violence event (64 vs. 32%, respectively, χ2(2) = 95.1, P < 0.001). The proportion of exposed persons meeting PTSD criteria was lower in males than females (8 vs. 11%, respectively), but the difference was not significant (χ2(2) = 1.58, P = 0.21).

Growth models and trajectory classes, exposure to traumatic events and the conditional risk of PTSD

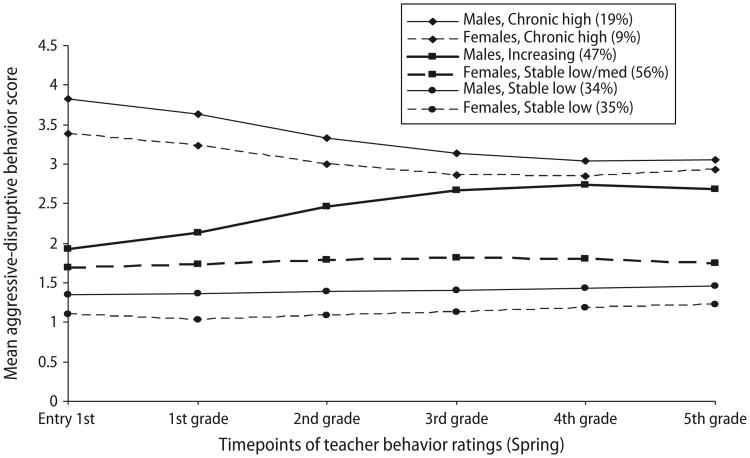

Three distinct behavior trajectories were found among the males as well as among females in unadjusted models and in models where covariates were included (Fig. 1). Covariates that according to theory should distinguish classes, were found to vary statistically between classes in the expected directions (Table 2), providing evidence that the derived classes represent meaningful population heterogeneity.

Fig. 1. Female and male trajectories of aggressive-disruptive behavior over time, adjusted for the effects of covariates (race, free lunch status, concentration problems, peer rejection, and reading achievement).

Table 2. Covariate differencesa between aggressive-disruptive behavior trajectory classes.

| Females | Males | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Stable low-med aOR (95% CI) | Chronic high aOR (95% CI) | Increasing aOR (95% CI) | Chronic high aOR (95% CI) | |

| Concentration problemsb | 2.2 (1.5–3.1) | 4.1 (2.0–8.6) | 1.7 (1.2–2.8) | 2.8 (1.8–4.3) |

| Peer rejectionb | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) | 2.3 (1.2–4.2) | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | 1.8 (0.8–4.2) |

| Reading readinessb | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) |

| Subsidized lunch | 1.5 (0.5–4.8) | 1.0 (0.3–4.2) | 1.4 (0.8–2.6) | 1.4 (0.5–4.1) |

| Minority | 1.8 (0.7–4.6) | 5.9 (1.1–32.5) | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) |

aOR from models including all other covariates listed with the gender specific stable low aggressive-disruptive behavior trajectory as the reference group

Scores standardized around the mean

A three-class solution was found to be optimal among males and showed good precision in class membership estimation (model without covariates: BIC = 6921.2, entropy = 0.75; model including covariates: BIC = 6067.7, entropy = 0.79). The three distinct aggressive-disruptive behavior trajectories identified were: a persistent chronic high aggressive-disruptive behavior trajectory (19% of males); an increasing aggressive-disruptive behavior trajectory (47% of males); and a stable low aggressive-disruptive behavior trajectory (34% of males). Table 3 provides the cumulative prevalence of exposure to any traumatic event and to assaultive violence traumas for males classified into the three behavioral trajectories as well as odds ratio estimates. Relative to males with stable low aggressive-disruptive behavior, males in the increasing and chronic high aggressive-disruptive behavioral classes were three-four times more likely to experience assaultive violence events. No differences were noted between the class memberships and exposure to any traumatic event. While the association between assaultive violence trauma for males in the chronic high class did not differ significantly from the association for males in the increasing aggressive-disruptive behavior class, the prevalence of exposure was higher for males in the increasing aggressive-disruptive trajectory. The prevalence of PTSD was also highest among males with increasing aggressive-disruptive behavior than males in other behavior groups, however, no differences were detected in the conditional risk for PTSD following exposure to a traumatic event across the three behavioral trajectory classes.

Table 3. Gender specific aggressive-disruptive behavioral trajectory classes and the cumulative incidence and association with traumatic event experiences by young adulthood.

| n (%) | Exposed to any traumatic event | Exposed to assaultive violence | Posttraumatic stress disorder | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral trajectory class and prevalence (95% confidence interval) of experiences | ||||||||||||

| Males | ||||||||||||

| CHAD, chronic high aggressive-disruptive | 76 (19%) | 94.4 (88.4–100) | 75.6 (61.7–89.4) | 1.6 (0–4.6) | ||||||||

| IAD, Increasing aggressive-disruptive | 190 (47%) | 86.5 (81.0–91.9) | 83.6 (76.1–91.2) | 11.5 (5.9–17.1) | ||||||||

| SLAD, stable low aggressive-disruptive | 136 (34%) | 86.8 (80.1–93.4) | 52.9 (41.4–64.4) | 6.1 (0.8–11.5) | ||||||||

| Females | ||||||||||||

| CHAD, chronic high aggressive-disruptive | 40 (9%) | 84.6 (73.2–96.1) | 43.7 (18.1–69.4) | 0 | ||||||||

| LAD, low-moderate aggressive-disruptive | 243 (56%) | 78.8 (72.8–84.9) | 40.5 (32.2–48.9) | 13.7 (7.5–20.0) | ||||||||

| SLAD, stable low aggressive-disruptive | 152 (35%) | 74.7 (66.7–82.8) | 41.0 (32.5–49.5) | 8.2 (3.1–13.4) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Among males only | Among females only | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | aOR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | aOR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Behavioral trajectory class and associations with experiencesa | ||||||||||||

| Exposure: any traumatic event | ||||||||||||

| CHAD vs. SLAD | 2.3 | (0.8–6.6) | 0.10 | 2.6 | (0.8–8.4) | 0.11 | 2.1 | (0.8–5.5) | 0.29 | 1.9 | (0.7–5.1) | 0.22 |

| IAD(M)/LAD(F) vs. SLAD | 1.2 | (0.5–2.6) | 0.67 | 1.0 | (0.4–2.2) | 0.99 | 1.2 | (0.7–2.1) | 0.42 | 1.3 | (0.7–2.2) | 0.49 |

| CHAD vs. IAD(M)/LAD(F) | 2.0 | (0.6–6.4) | 0.26 | 2.6 | (0.7–9.7) | 0.16 | 1.7 | (0.6–4.7) | 0.12 | 1.5 | (0.5–4.2) | 0.45 |

| Type of exposure: assaultive violence | ||||||||||||

| CHAD vs. SLAD | 2.9 | (1.4–6.2) | 0.01 | 2.8 | (1.2–6.1) | 0.01 | 1.8 | (0.7–4.7) | 0.24 | 1.1 | (0.4–3.4) | 0.89 |

| IAD(M)/LAD(F) vs. SLAD | 3.9 | (2.1–7.1) | <0.001 | 4.5 | (2.2–9.2) | <0.001 | 1.3 | (0.8–1.9) | 0.27 | 1.0 | (0.6–1.7) | 0.94 |

| CHAD vs. IAD(M)/LAD(F) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.7) | 0.46 | 0.6 | (0.2–1.9) | 0.42 | 1.4 | (0.5–4.0) | 0.52 | 1.1 | (0.4–3.6) | 0.87 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | ||||||||||||

| CHAD vs. SLAD | 0.3 | (0.1–1.6) | 0.14 | 0.2 | (0.1–1.6) | 0.15 | 0.8 | (0.1–10.2) | 0.90 | |||

| IAD(M)/LAD(F) vs. SLAD | 1.9 | (0.7–5.2) | 0.18 | 2.0 | (0.6–6.6) | 0.29 | 1.9 | (0.8–4.4) | 0.11 | 1.8 | (0.7–4.4) | 0.22 |

| CHAD vs. IAD(M)/LAD(F) | 0.1 | (0.1–1.0) | 0.05 | 0.1 | (0.1–1.1) | 0.07 | 0.4 | (0.1–5.8) | 0.53 | |||

OR odds ratio, 95% CI 95% confidence interval, aOR adjusted odds ratio, covariates of subsidized lunch, race, reading achievement, attention-concentration problems, and peer rejection

A three-class solution was also found to be optimal among females (model without covariates: BIC = 5925.6, entropy = 0.80; model including covariates: BIC = 5585.4, entropy = 0.87). The female model identified three distinct trajectories of aggressive behavior: a chronic high aggressive-disruptive behavior trajectory (9% of females), a low moderate aggressive-disruptive behavior trajectory (56% of females); and a stable low aggressive-disruptive behavior trajectory (35% of females). Table 3 shows little difference in the cumulative prevalence of exposure for the three female behavioral trajectories. Contrary to the finding in males, membership in the class with the highest aggressive behavior trajectory (i.e., chronic high) did not increase a female's likelihood for exposure to assaultive violence events, relative to females in the stable low/medium and stable low classes. Similar to the findings in males, no association was detected between the conditional risk for PTSD following exposure and class trajectories in females.

Discussion

Our findings indicate sex differences in the course of early childhood aggressive-disruptive behavior might in part account for sex differences in experiencing traumatic events. Among females, there was very little variation in the association linking the various trajectories of aggressive-disruptive behavior with exposure to traumatic events. Contrary to our expectations, females in the stable high class did not experience increased exposure to assaultive traumatic events. In contrast, among males, two different behavioral trajectory groups (chronic high and increasing aggressive/disruptive problems) were associated with an increased probability of experiencing assaultive violence by young adulthood. Noteworthy is the finding that the odds of being exposed to assaultive violence and the frequency of PTSD (due to higher occurrence exposure) was the highest among males with an increasing problem trajectory; even higher than among males with persistently high levels of aggressive-disruptive behavior initially detected at age 6 (the chronic high trajectory). It appears that a single behavioral assessment at an early age (e.g., entry into first grade) would be grossly inadequate for identifying males at risk for traumatic events. We found no evidence that the course of early aggression was associated with the probability of PTSD following exposure, that is, early aggression had no relationship with the PTSD- response to traumatic events. However, because subsets of the population with higher risk of exposure to traumatic events have higher occurrence of PTSD, the optimal prevention of PTSD is the reduction of persons' risk of exposure to traumatic events.

This paper builds on previous studies by bringing in a developmental perspective that stresses that research examining childhood risk factors needs to consider the developmental course, which includes not only changes that occur with age but also gender differences. Few studies have addressed the developmental course of early childhood factors and how they may relate to trauma exposure and PTSD among community epidemiologically defined cohorts. Our findings demonstrate that the risk estimate of the association is very dependent on the age at which it is assessed. Furthermore, since the course of aggressive-disruptive behavior in early childhood varies by sex, an approach that begins by exploring the association within the female and male subsamples separately is necessary.

The interpretation of the results should take into account several limitations and strengths of the study. Attrition is always a concern in prospective studies, although follow-up over the 15 year period from childhood to the mobile life stage of young adulthood was very good. Maladaptive behavior in early childhood was rated by teachers who are familiar with children's functioning in school environments. However, respondents' accounts of past events—even traumatic events that might be expected to be memorable—are subject to reporting errors. In this study, the occurrence of lifetime trauma and PTSD was assessed at a young age (mean 21 years), which may attenuate concerns of recall bias. The assessment of PTSD was conducted by non-clinicians, using a structured interview without access to supplementary information that might be elicited by clinicians. Blind clinical assessments have found high concordance with the structured interview and assessment procedure [7]. A range of other factors, including family or genetic factors, were not measured and it is possible that the mechanisms underlying the exposure to non assaultive violence traumatic events and the development of PTSD are different from those involving assaultive violence.

Previous studies have found that children with high levels of behavior problems as rated by teachers at an early age were at increased risk for exposure to traumatic events [27], particularly assaultive violent events [8, 46]. This study advances these previous findings by suggesting that the trajectory or age at which behavior is assessed in early childhood may be a critical component for accuracy as well as suggesting possible mechanisms when estimating the link between maladaptive behavior and traumatic exposures and PTSD. For example, assessments of behavioral problems at the start of schooling may represent more faithfully early predispositions. Whereas as proposed in a model of conduct disorder in relation to early neurodevelopmental deficits [36], adolescent behavior becomes increasingly influenced by environmental responses. Thus, our findings suggest that a group of vulnerable individuals may be identified by their behavioral responses when challenged with the task of beginning schooling, but there may also be a group of individuals at increased risk that emerges as their behavior is formed in response to external conditions. A substantial number of males who were not rated as having high levels of aggressive-disruptive problems at age 6 were captured only when taking into account their longitudinal pattern of behavior over the subsequent few years.

Our findings are consistent with the literature suggesting a possible gender specific etiologic role of antisocial behavior increasing risk of exposure to assault [12, 45]. The small sample size and relatively low occurrence of PTSD diminished our statistical power to declare with certainty how our findings agree or differ from others who find an association between externalizing behavior and the conditional risk of PTSD [26]. Replications in larger cohorts are needed as neurocognitive models postulate that self regulation or behavior adaptation influence the susceptibility to PTSD symptoms [25]. This study failed to detect an increase in cumulative occurrence of PTSD among individuals with a history of stable high aggressive-disruptive behaviors. However, alternative explanations must be ruled out, such as under reporting of symptoms by young adults with antisocial personality characteristics and desensitization, where long term chronic exposure to violence as a part of inner-city life may diminish the reaction to traumas [14, 43].

Considering the potential benefits of reducing posttraumatic psychopathology, it is important to develop better means of identifying traumatized individuals who may require interventions to prevent the development of impairment associated with PTSD. Stable factors, such as gender, may be useful in identifying individuals most vulnerable to exposure and PTSD at almost any assessment obtained at any time, but a malleable variable, such as behaviors, can provide better information for interventions. The manifestation of psychopathology may change depending on the developmental stage of the individual. Our findings illustrate the importance of monitoring behavior changes during childhood when exploring the link between aggressive-disruptive behavior and exposure to traumatic events. They suggest that the etiological role of childhood externalizing behaviors in increasing the risk of experiencing a traumatic event differs by gender. Future research may provide a better understanding of the mechanisms of how a behavioral risk factor and its timing may change or interact with brain development.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants MH 71395 and MH 48802 from the National Institute of Mental Health and grants DA09897 and DA04392 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Contributor Information

Dr. Carla L. Storr, Email: cstor002@son.umaryland.edu, Dept. of Family and Community Health, University of Maryland, Baltimore, School of Nursing, 655 West Lombard Street, Baltimore (MD) 21201, USA, Tel.: +1-410/706-5540, Fax: +1-410/706-2388.

Cindy M. Schaeffer, Dept. of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston (SC), USA

Hanno Petras, Dept. of Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Maryland, College Park, Baltimore (MD), USA.

Nicholas S. Ialongo, Dept. of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore (MD), USA

Naomi Breslau, Dept. of Epidemiology, Michigan State University, College of Human Medicine, East Lansing (MI), USA.

References

- 1.Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: issues and techniques. Erlbaum; Mahwah: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brame B, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE. Developmental trajectories of physical aggression from school entry to late adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42:503–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:216–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270028003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, Schultz L. Psychiatric sequelae of posttraumatic stress disorder in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:81–87. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130087016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslau N, Kessler RC. The stressor criterion in DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder: an empirical investigation. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:699–704. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit area survey of trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breslau N, Kessler RC, Peterson EL. PTSD assessment with a structured interview: reliability and concordance with a standardized clinical interview. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1998;7:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breslau N, Lucia VC, Alvarado GF. Intelligence and other predisposing factors in exposure to trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a follow-up study at age 17 of a cohort first assessed at age 6 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breslau N, Peterson EL, Poisson LM, Schultz LR, Lucia VC. Estimating post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: lifetime perspective and the impact of typical traumatic events. Psychol Med. 2004;34:889–898. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breslau N, Wilcox HC, Storr CL, Lucia VC, Anthony JC. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder: a study of youths in urban America. J Urban Health. 2004;81:530–544. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cottler LB, Nishith P, Compton WM. Gender differences in risk factors for trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder among inner-city drug abusers in and out of treatment. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:111–117. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ensminger ME, Forrest CB, Riley AW, Kang M, Green BF, Starfield B, Ryan SA. The validity of measures of socio-economic status of adolescents. J Adolesc Res. 2000;15:392–419. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzpatrick KM. Exposure to violence and presence of depression among low-income, African–American youth. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:528–531. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford T, Goodman R, Meltzer H. The British child and adolescent mental health survey 1999: the prevalence of DSM-IV disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1203–1211. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200310000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ford JD, Racusin R, Ellis CG, Davis WB, Reiser J, Fleischer A, Thomas J. Child maltreatment, other trauma exposure, and posttraumatic symptomatology among children with oppositional defiant and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders. Child Maltreat. 2000;5:205–217. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, Silverman AB, Pakiz B, Frost AK, Cohen E. Traumas and posttraumatic stress disorder in a community population of older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1369–1380. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199510000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ialongo N, McCreary BK, Pearson JL, Koenig AL, Schmidt NB, Poduska J, Kellam SG. Major depressive disorder in a population of urban, African–American young adults: prevalence, correlates, comorbidity and unmet mental health service need. J Affect Disord. 2004;79:127–136. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingoldsby EM, Shaw DS. Neighborhood contextual factors and early-starting antisocial pathways. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2002;5(1):21–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1014521724498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jang KL, Stein MB, Taylor S, Asmundson GJ, Livesley WJ. Exposure to traumatic events and experiences: aetiological relationships with personality function. Psychiatry Res. 2003;120:61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kellam SG, Ling X, Merisca R, Brown CH, Ialongo N. The effect of the level of aggression in the first grade classroom on the course and malleability of aggressive behavior into middle school. Dev Psychopathol. 1998;10:165–185. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kellam SG, Werthamer-Larsson L, Dolan LJ, Brown CH, Mayer LS, Rebok GW, Anthony JC, Laudolff J, Edelsohn G. Developmental epidemiologically-based preventive trials: baseline modeling of early target behaviors and depressive symptoms. Am J Community Psychol. 1991;19:563–584. doi: 10.1007/BF00937992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koenen KC. Developmental epidemiology of PTSD: self-regulation as a central mechanism. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1071:255–266. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koenen KC, Fu QJ, Lyons MJ, Toomey R, Goldberg J, Eisen SA, True W, Tsuang M. Juvenile conduct disorder as a risk factor for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18:23–32. doi: 10.1002/jts.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koenen KC, Moffitt TE, Poulton R, Martin J, Caspi A. Early childhood factors associated with the development of post-traumatic stress disorder: results from a longitudinal birth cohort. Psychol Med. 2007;37:181–192. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Little RJ. Modeling the dropout mechanism in repeated-measures studies. J Am Stat Assoc. 1995;90:1112–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McFadyen-Ketchum SA, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS. Patterns of change in early childhood aggressive-disruptive behavior: gender differences in predictions from early coercive and affectionate mother-child interactions. Child Dev. 1996;67:2417–2433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McFarlane A. The contribution of epidemiology to the study of traumatic stress. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:872–882. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0870-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mills MA, Edmondson D, Park CL. Trauma and stress response among Hurricane Katrina evacuees. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:S116–S123. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.086678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moffitt TE. Adolescent-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muthén B. Latent variable analysis: growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. Handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Sage Publications; Newbury Park: 2004. pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muthén B, Muthén LK. Mplus users guide. Muthén and Muthén; Los Angeles: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muthén B, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;6:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perkonigg A, Kessler RC, Storz S, Wittchen HU. Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: prevalence, risk factors, and comorbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:46–59. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101001046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petras H, Chilcoat HD, Leaf PJ, Ialongo NS, Kellam SG. The utility of teacher ratings of aggression during the elementary school years in identifying later violence in adolescent males. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;1:88–96. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petras H, Ialongo N, Lambert SF, Barrueco S, Schaeffer CM, Chilcoat H, Kellam S. The utility of elementary school TOCA-R scores in identifying later criminal court violence among adolescent females. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:790–797. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000166378.22651.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petras H, Schaeffer CM, Ialongo N, Hubbard S, Muthen B, Lambert SF, Poduska J, Kellam S. When the course of aggressive behavior in childhood does not predict antisocial outcomes in adolescence and adulthood: an examination of potential explanatory variables. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16:919–941. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Cottler LB, Goldring E. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule, version III revised. Washington University; St. Louis: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaeffer CM, Petras H, Ialongo N, Masyn KE, Hubbard S, Poduska J, Kellam S. A comparison of girls' and boys' aggressive-disruptive behavior trajectories across elementary school: prediction to young adult antisocial outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:500–510. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwab-Stone ME, Ayers TS, Kasprow W, Voyce C, Barone C, Shriver T, Weissberg RP. No safe haven: a study of violence exposure in an urban community. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1343–1352. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199510000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein MB, Hofler M, Perkonigg A, Lieb R, Pfister H, Maercker A, Wittchen HU. Patterns of incidence and psychiatric risk factors for traumatic events. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2002;11:143–153. doi: 10.1002/mpr.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Storr CL, Ialongo N, Anthony JC, Breslau N. Childhood antecedents of exposure to traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder: a prospective study from first grade of school to early adulthood. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(1):119–125. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Storr CL, Ialongo NS, Kellam SG, Anthony JC. A randomized controlled trial of two primary school intervention strategies to prevent early onset tobacco smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tolin DF, Foa EB. Sex differences in trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:959–992. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wardrop JL. Review of the California achievement tests, forms E and F. In: Close J, Conoley J, Kramer J, editors. The tenth mental measurements yearbook. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln; 1989. pp. 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Werthamer-Larsson L, Kellam SG, Wheeler L. Effect of first-grade classroom environment on child shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and concentration problems. Am J Community Psychol. 1991 doi: 10.1007/BF00937993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.World Health Organization. Composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI), version 2.1. WHO; Geneva: 1997. [Google Scholar]