Abstract

In the field of energetics and cancer, little attention has been given to whether energy balance directed interventions designed to regulate body weight by increasing energy expenditure versus reducing energy intake have an equivalent impact on the development of breast cancer. The objective of this experiment was to determine the effects on mammary carcinogenesis of physical activity (PA), achieved via running on an activity wheel, or restricted energy intake (RE). Food intake of PA and RE rats was controlled so that both groups had the same net energy balance determined by growth rate, that was 92% of the sedentary control group (SC). A total of 135 female Sprague Dawley rats were injected with 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea (50 mg/kg) and 7 days thereafter were randomized to either SC, PA, or RE. Mammary cancer incidence was 97.8%, 88.9% and 84.4% and cancer multiplicity was 3.66, 3.11, and 2.64 cancers/rat in SC, RE, and PA, respectively (SC vs. PA, p=0.02 for incidence and p=0.03 for multiplicity). Analyses of mammary carcinomas revealed that cell proliferation associated proteins were reduced and caspase 3 activity and pro-apoptotic proteins were elevated by PA or RE relative to SC (p<0.05). It was observed that these effects may be mediated, in part, by activation of AMP-activated protein kinase and down regulation of protein kinase B and the mammalian target of rapamycin.

Keywords: physical activity, restricted energy intake, mammalian target of rapamycin, AMP-activated protein kinase, mammary carcinogenesis

Introduction

At any age, positive energy balance can result in weight gain. When positive energy balance is excessive over time it is associated with overweight and obesity that are predisposing factors for a number of chronic diseases including breast cancer [1–4]. The occurrence of overweight and obesity is increasing in this country and globally at an epidemic rate [5;6]. Clearly, the prevention of excessive weight gain is an important focus of efforts to combat this problem. One of the recommendations that is widely publicized for weight gain prevention is to limit energy intake and increase energy expenditure by being physically active [5;6]. These are sound recommendations; however, it is not clear if limiting weight gain by one method or the other will have the same effect on a disease process like breast carcinogenesis that is known to be sensitive to energy availability. There are a number of reasons that a difference in response might be anticipated. They include: 1) PA induces a greater flux of energy through the system that could alter redox sensitive cell signaling via the induction of oxidative stress; whereas, RE reduces oxidative stress [7], and 2) PA, depending on its type, intensity, duration, and frequency, induces a pro-inflammatory response and chronic inflammation both of which have been associated with enhancing cancer risk in a number of organ sites; whereas reduced energy intake is associated with suppression of inflammation [8;9]. To our knowledge, no comparative studies of the effects of these interventions have been published. In this paper we report an initial set of experiments designed to determine the effects of physical activity (PA) and restricted energy intake (RE) on the carcinogenic response in the mammary gland when they exert the same effects on body weight gain and to investigate the mechanisms by which energetically comparable levels of PA or RE exert their effects.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Primary antibodies used in this study were anti-cyclin D1, anti-E2F-1, and anti-p27Kip1from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Fremont, CA), anti-retinoblastoma (Rb), anti-Bcl-2, anti-hILP/XIAP, and anti-Bax from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA), anti-apoptosis protease-activating factor 1 (Apaf-1) from Millipore (Billerica, MA), anti-phospho-AMPK (Thr172), anti-AMPK, anti-phospho-acetyl-CoA-carboxylase (ACC) (Ser79), anti-ACC, anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473), anti-Akt, anti-phospho-mTOR (Ser2448), anti-mTOR, anti-phospho-p70S6K (Thr389), anti-p70S6K, anti-phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46), anti-4E-BP1, and anti-rabbit immunoglobulin-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, as well as LumiGLO reagent with peroxide, all from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-p21Cip1 and anti-mouse immunoglobulin-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse anti-β-actin primary antibody was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO).

Experimental design

One hundred and thirty-five female Sprague Dawley rats were obtained from Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY at 20 days of age. At 21 days of age, rats were injected with 50 mg 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea/kg body weight (i.p.) as previously described [10]. Rats were housed individually in solid bottomed polycarbonate cages. Six days following carcinogen injection, all rats were evenly randomized into one of three groups, a physically active group (PA), a group given a restricted amount of food (RE), or a sedentary control group (SC). Each PA rat was paired to a RE rat and the amount of food given the RE rat permitted it to gain body weight at the same rate as its PA-pair mate. Rats were fed pellet diet (TestDiet, Richmond, IN, Cat# 1811155). The composition of the diet included sucrose, casein, maltodextrin, corn starch, corn oil, cellulose, minerals, silcon dioxide, vitamins, magnesium stearate, DL-methionine. The energy distribution was protein, 20.5%, fat, 12.7% and carbohydrates, 66.8% and the energy density is 3.48 kcal/g. Animal rooms were maintained at 22 ± 1°C with 50% relative humidity and a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. Rats were weighed daily and were palpated for detection of mammary tumors twice per wk starting from 29 days post carcinogen. The work reported was reviewed and approved by the Colorado State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted according to the committee guidelines.

Physical Activity

In this study, a newly developed wheel running instrument was used to investigate how PA affects the carcinogenic process in the mammary gland. This instrument overcomes a number of problems that have limited the study of PA and cancer in experimental models (reviewed in [11;12]). PA animals were given free access to an activity wheel and their running behavior was reinforced via the periodic distribution of food of a predetermined amount for a prescribed distance run. This process was automated via the use of a pellet dispenser whose function was integrated with the running wheel under computer control. A proximity sensor was used to verify that the animal was actually running in the wheel.

Necropsy

Following an overnight fast, rats were killed over a 3-hour time interval via inhalation of gaseous carbon dioxide. The sequence in which rats were euthanized was stratified across groups so as to minimize the likelihood that order effects would masquerade as treatment associated effects. After the rat lost consciousness, blood was directly obtained from the retro-orbital sinus and gravity fed through heparinized capillary tubes (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) into EDTA coated tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for plasma. The bleeding procedure took approximately 1 min/rat. Plasma was isolated by centrifugation at 1000 x g for 10 min at room temperature. Following blood collection and cervical dislocation, rat was then skinned and the skin to which the mammary gland chains were attached was examined under translucent light for detectable mammary pathologies. All grossly detectable mammary gland lesions were excised for histological classification. When size was sufficient, a piece of each tumor was also immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Western Blotting

Mammary carcinomas were homogenized in lysis buffer [40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1% Triton X-100, 0.25 M sucrose, 3 mM EGTA, 3 mM EDTA, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenyl-methylsulfony fluoride and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA)]. The lysates were centrifuged at 7,500 x g for 10 min in a tabletop centrifuge at 4°C and clear supernatant fractions were collected and stored at −80°C. The protein concentration in the supernatants was determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Western blotting was performed as described previously [13]. Briefly, 40 μg of protein lysate per sample was subjected to 8–16% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gradient gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) after being denatured by boiling with SDS sample buffer [63 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 50 mM DTT, and 0.01% bromophenol blue] for 5 minutes and the proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The levels of cyclin D1, E2F-1, Rb, p21Cip1, p27Kit1, Bcl-2, hILP/XIAP, Bax, Apaf-1, phospho-AMPK (Thr172), AMPK, phospho-ACC (Ser79), ACC, phospho-Akt (Ser473), Akt, phospho-mTOR (Ser2448), mTOR, phospho-p70S6K (Thr389), p70S6K, phospho-4E-BP1(Thr37/46), 4E-BP1, and β-actin were determined using specific primary antibodies, followed by treatment with the appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and visualized by LumiGLO reagent Western blotting detection system. The chemiluminescence signal was captured using a ChemiDoc densitometer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) that is equipped with a CCD camera having a resolution of 1300 x 1030 and run under the control of Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and analyzed by the software. The actin-normalized scanning density data were reported.

Caspase 3 Activity Assay

Caspase 3 activity was determined using EnChek Caspase Assay Kit #2 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the instruction provided by the company. Briefly, samples were prepared in 1X lysis buffer (pH 7.5, Invitrogen) and 50 μL of the sample was incubated with caspase-3 substrate Z-DEVD-R110 (Invitrogen) at room temperature for 30 minutes. The caspase 3 activity was quantified by measuring the fluorescence with excitation at 496 nm and emission at 520 nm using 96 well plate reader SpectraMax M5 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The protein concentration in the sample was determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The caspase 3 activity was expressed as nM/min/mg protein of Rhodamine 110 that is a caspase 3 catalyzed product of Z-DEVD-R110 substrate by measuring the Rhodamine 110 as reference standard at the same time.

Statistical Analyses

Differences among groups in the incidence and multiplicity of mammary carcinomas were evaluated, respectively, by chi-square analysis [14] or ANOVA after square root transformation of tumor count as recommended in [15]. Differences among groups in the body weight were analyzed by ANOVA [16]. For Western blots, representative western bands were shown in the figures. The data shown in the tables were either the actin-normalized scanning data for proteins involved in cell cycle, apoptosis, and energy sensing pathways or the ratio of the actual scanning units derived from the densitometric analysis of each Western blot for the phospho-proteins involved in energy sensing pathways. For statistical analyses, the actin-normalized scanning density data obtained from the ChemiDoc scanner using Quantity One (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were first rank transformed. This approach is particularly suitable for semi-quantitative measurements that are collected as continuously distributed data as is the case with Western blots The ranked data were then subjected to multivariate analysis of variance [17]. Ratio data were computed from the scanning units derived from the densitometric analysis, i.e. the arbitrary units of optical density for variables stated and then the ratios were rank transformed and evaluated via multivariate analysis of variance. All analyses were performed using Systat statistical analysis software, Version 12. Data were also subjected to principal components analysis using the Partek Software analysis suite [18].

Results

Physical activity and growth

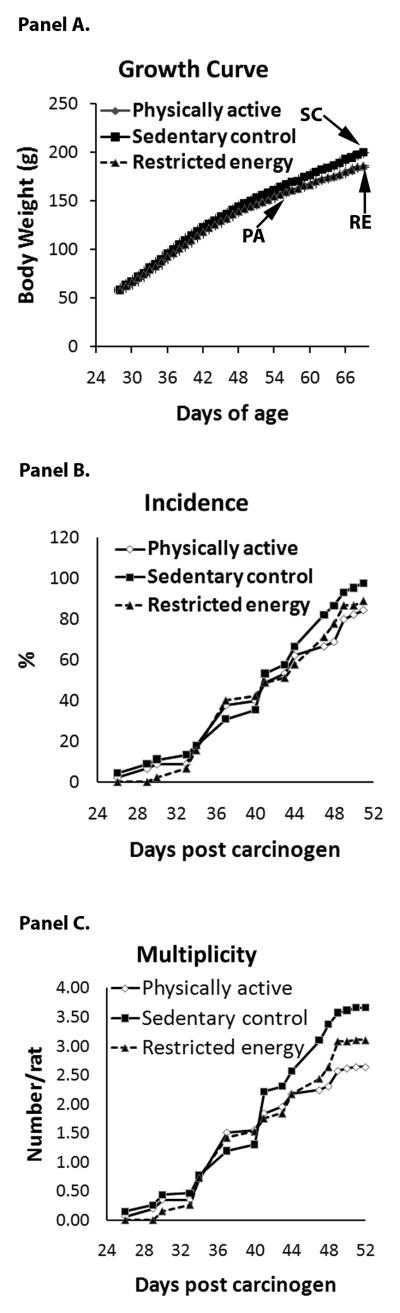

A total of 135 rats were assigned to the study: 45 sedentary control (SC) rats, 45 physical activity (PA) rats, and 45 restricted food (RE) rats. The average distance run per day by the 45 PA rats was 7,673 ± 525 m/day or approximately 5 miles per day, a distance similar to that walked by an individual who meets the national recommendation of walking 10,00 steps per day. As shown in Figure 1 rats in the PA or RE groups grew at the same rate throughout the study. By the end of the carcinogenesis experiment, the average final body weight of SC rats (200.5 g) was 8% higher than that of PA (185.0) or RE rats (186.8) that differed from PA by less than 1% (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Growth curves, cancer incidence and multiplicity of sedentary control (SC), restricted energy (RE), and physically active (PA) rats. Values are mean ± SEM for each point of body weight. Differences among groups were analyzed by ANOVA. From 46 days of age until the end of the experiment, significant differences between SC and RE or PA were observed (p<0.05). No significant difference was observed at any time point between RE and PA.

Table 1.

Effect of physical activity on final body weight and the carcinogenic response in the mammary gland

| Treatment | N | Carcinogenic Response* | Final Body Weight (g)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Incidence (%) | Number cancers/rat | Median mass/rat (g) | (g) | ||

| Sedentary control | 45 | 97.8 | 3.66 ± 0.36 | 0.41 | 200.5 ± 1.6 |

| Restricted energy | 45 | 88.9 | 3.11 ± 0.32 | 0.30 | 186.8 ± 1.4†† |

| Physically active | 45 | 84.4† | 2.64 ± 0.28† | 0.16 | 185.0 ± 1.5†† |

For cancer multiplicity and final body weight, values are means ± SEM. For tumor mass, values are medians. Data were analyzed by ANOVA and difference among groups was evaluated Bonferroni. Compared to sedentary control,

p<0.05,

p<0.01.

Carcinogenic response

Greater than 97% of the mammary tumors detected at necropsy were adenocarcinomas and the distribution of benign versus malignant tumors did not differ by treatment group (data not shown). The effect of PA on the carcinogenic response is shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, Panels B and C. Mammary cancer incidence was 97.8%, 88.9% and 84.4% and cancer multiplicity was 3.66, 3.11, and 2.64 cancers/rat in SC, RE, and PA, respectively (SC vs. PA, p=0.02 for incidence and p=0.03 for multiplicity). The median tumor mass per rat was reduced by PA or RE compared to SC, which was 0.41, 0.30, and 0.16 in SC, RE, and PA, respectively.

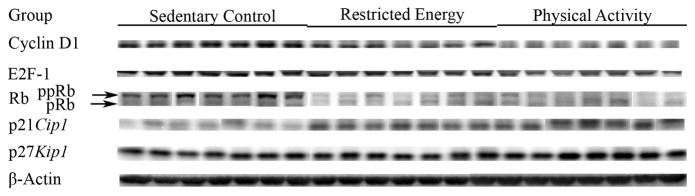

Cell proliferation and apoptosis

Mammary carcinomas were analyzed by Western blotting and activity assay for proteins involved in cell proliferation and apoptosis. The table 2 and Figure 2 provides the average values for each protein assessed and shows the Western blots for these proteins for each carcinoma that was evaluated. Levels of cyclin D1, hyper phosphorylated Rb and E2F-1, were reduced and p21 and p27 were elevated in PA versus SC and the response in RE was intermediate to that observed in PA and SC. Multivariate analysis of variance indicated that the pattern of change observed was significant (Hotelling-Lawley statistic, p=0.0026) with the univariate statistics indicating that the greatest effects were on cyclin D1 (p=0.046), p21 (p<0.0006), and ppRb (p=0.039).

Table 2.

Effect of physical activity on cell proliferation related molecules in mammary carcinomas *

| Group | Sedentary Control | Restricted Energy | Physically Active |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclin D1 | 33.5 ± 3.0 | 29.4 ± 1.9 | 25.0 ± 1.4† |

| E2F-1 | 34.3 ± 3.7 | 32.1 ± 2.9 | 30.0 ± 2.9 |

| ppRb | 19.3 ± 4.0 | 9.5 ± 1.1† | 14.7 ± 1.2 |

| pRb | 16.6 ± 3.7 | 9.9 ± 0.7 | 15.7 ± 1.1 |

| Rb | 16.8 ± 3.4 | 9.0 ± 0.9† | 14.5 ± 0.9 |

| ppRb/Rb | 1.14 ± 0.07 | 1.05 ± 0.04 | 1.01 ± 0.04 |

| ppRb/pRb | 1.18 ± 0.16 | 0.95 ± 0.07 | 0.95 ± 0.07 |

| P21Cip1 | 13.6 ± 7.0 | 20.5 ± 0.9†† | 21.0 ± 0.8†† |

| P27Kip1 | 32.5 ± 3.4 | 34.1 ± 3.3 | 35.8 ± 2.8 |

The levels of proteins (relative absorbance unit x 10x4) or the ratio of hyper-phosphorylated Rb (ppRb) to Rb (ppRb/Rb) and the ratio of hyper-phosphorylated Rb (ppRb) to hypo-phosphorylated Rb (ppRb/pRb) are shown; values are mean ± SEM, n=7 per treatment group. The images shown in Figure 2 are those directly acquired from the ChemiDoc work station that is equipped with a CCD camera having a resolution of 1300 x 1030. The normalized intensity data from the ChemiDoc were evaluated; statistical analyses were done on the ranks of the absorbance data via multivariate analysis of variance as described in the Materials and Methods section. Compared to sedentary control,

p<0.05,

p<0.01.

Figure 2.

Western blot images of cell cycle regulatory proteins in mammary carcinomas from sedentary control, restricted energy, and physically active rats: cyclin D1, E2F-1, retinoblastoma (Rb), p21Cip1 and p27Kip.

Table 3 and Figure 3 show caspase 3 activity, an indicator of apoptosis induction and Western blots for proteins involved in apoptosis. Caspase 3 activity was induced by PA or RE relative to SC (p<0.001). Mammary carcinomas from PA rats had lower levels of BCL-2 and XIAP and higher levels of BAX, Apaf-1 and caspase 3 activity (similar effect was also observed in mammary gland, data was not shown) than found in carcinomas from SC rats. The levels observed in carcinomas from RE rats were intermediate to those observed in PA and SC carcinomas. This pattern of protein expression is consistent with PA inducing a pro-apoptotic environment (Hotelling-Lawley multivariate statistic, p=0.018). Univariate statistics from the multivariate analysis indicated that the effects of PA on BAX (p=0.044), BCL-2 (p=0.009), XIAP (p=0.003) were significant.

Table 3.

Effect of physical activity on apoptosis related molecules and activity in mammary carcinomas *

| Group | Sedentary Control | Restricted Energy | Physically Active |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bcl-2 | 23.0 ± 1.7 | 20.0 ± 0.7 | 17.5 ± 0.7†† |

| XIAP | 20.9 ± 1.3 | 18.6 ± 0.9† | 15.5 ± 0.5†† |

| Bax | 22.1 ± 1.4 | 26.1 ± 1.1 | 27.4 ± 1.7† |

| Apaf-1 | 28.3 ± 1.3 | 30.6 ± 3.4 | 30.4 ± 0.9 |

| Caspase 3 activity | 144 ± 4 | 171 ± 5†† | 166 ± 8†† |

The levels of proteins (relative absorbance unit x 10x4) and caspase 3 activity expressed as nM/min/mg protein of Rhodamine 110 that is a caspase 3 catalyzed product of Z-DEVE-R110 substrate are shown; values are mean ± SEM, n=7 per treatment group. The images shown in Figure 3 are those directly acquired from the ChemiDoc work station that is equipped with a CCD camera having a resolution of 1300 x 1030. The normalized intensity data from the ChemiDoc were evaluated; statistical analyses were done on the ranks of the absorbance data via multivariate analysis of variance as described in the Materials and Methods section. XIAP: human X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein; Apaf-1: apoptosis protease-activating factor 1. Compared to sedentary control,

p<0.05,

p<0.01.

Figure 3.

Western blot images of proteins or activity involved in the regulation of apoptosis in mammary carcinomas from sedentary control, restricted energy, and physically active rats: Bcl-2, human X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), Bax, apoptosis protease-activating factor 1 (Apaf-1).

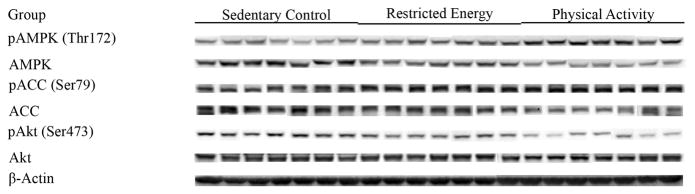

Signaling pathways

Exploratory analyses were conducted of the hypothesis that PA and RE would be associated with higher levels of activated AMPK and lower levels of activated Akt relative to levels observed in carcinomas from SC rats. Western blots for the each protein in the pathway and its phosphorylated counterpart are shown in Figure 4, and the actual absorbance data normalized to beta-actin are in the table 4. These values were used to compute the ratios of phosphorylated to non-phosphorylated protein which were then rank transformed and analyzed by multivariate analysis of variance. The results of the multivariate analysis supported the working hypothesis (Hotelling-Lawley statistic, p=0.005). The univariate statistics from that analysis indicated that effects were significant on levels of activated AMPK (ratio of pAMPK/AMPK, p<0.0002), AMPK activity (ratio of pACC/ACC, p=0.02) and activated Akt (ratio of pAkt/Akt, p=0.059).

Figure 4.

Western blot images of proteins involved in energy sensing pathways in mammary carcinomas from sedentary control, restricted energy, and physically active rats: AMP-activated protein kinase (pAMPK, Thr172), AMPK, acetyl-CoA-carboxylase (pACC, Ser79), ACC, Akt (pAkt, Ser473), and Akt.

Table 4.

Effect of physical activity on the molecules of energy sensing pathway in mammary carcinomas*

| Group | Sedentary Control | Restricted Energy | Physically Active |

|---|---|---|---|

| pAMPK(Thr172) | 14.1 ± 1.7 | 15.5 ± 1.1 | 17.9 ± 2.6 |

| AMPK | 19.0 ± 2.6 | 17.5 ± 1.3 | 15.0 ± 1.3 |

| pAMPK/AMPK | 0.74 ± 0.03 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 1.19 ± 0.06†† |

| pACC(Ser79) | 20.3 ± 1.2 | 26.8 ± 2.9 | 26.6 ± 2.2 |

| ACC | 22.8 ± 1.4 | 24.9 ± 4.8 | 20.8 ± 2.3 |

| pACC/ACC | 0.89 ± 0.07 | 1.08 ± 0.13 | 1.28 ± 0.09† |

| pAkt(Ser473) | 13.3 ± 0.9 | 13.9 ± 1.9 | 9.7 ± 0.8 |

| Akt | 43.1 ± 3.1 | 49.7 ± 6.0 | 39.8 ± 3.0 |

| pAkt/Akt | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.01† |

The levels of proteins (relative absorbance unit x 10x4) or the ratio of phosphorylated to non phosphorylated protein are shown; values are mean ± SEM, n=7 per treatment group. The images shown in Figure 4 are those directly acquired from the ChemiDoc work station that is equipped with a CCD camera having a resolution of 1300 x 1030. The normalized intensity data from the ChemiDoc were evaluated; statistical analyses were done on the ranks of the absorbance data via multivariate analysis of variance as described in the Materials and Methods section. pAMPK: phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase; pACC: phosphorylated acetyl-CoA-carboxylase. Compared to sedentary control,

p<0.05,

p<0.01.

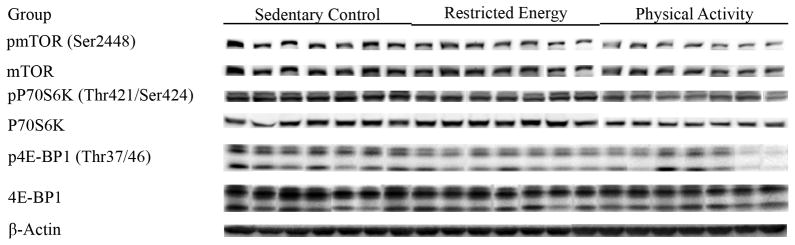

Based on these results, it was predicted that mTOR activity would be lower in mammary carcinomas from PA or RE relative to those from SC rats and that levels of its phosphorylated downstream targets, P70S6 kinase and 4E-BP1 would be reduced. Figure 5 shows Western blots for phospho-mTOR and two of activated mTOR’s substrates, P70S6 kinase and 4E-BP1 and the actual absorbance data normalized to beta-actin are in the table 5. Multivariate analysis of variance supported the exploratory hypothesis (Hotelling-Lawley statistic, p=0.0004). The univariate statistics from that analysis indicated that effects were significant on levels of activated mTOR (ratio of pmTOR/mTOR, p=0.043), P70S6 kinase (ratio of pP70S6K/P70S6K, p=0.003) and 4E-BP1 (ratio of p4E-BP1/4E-BP1, p<0.0004).

Figure 5.

Western blot images of mTOR and its downstream targets in mammary carcinomas from sedentary control (SC), restricted energy (RE), and physically active (PA) rats: mammalian target of rapamycin (pmTOR, Ser2448), 70-kDa ribosomal protein S6 kinase (pP70S6K, Thr389), and eukaryote initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (p4E-BP1, Thr37/46).

Table 5.

Effect of physical activity on the molecules of mTOR and its downstream targets in mammary carcinomas*

| Group | Sedentary Control | Restricted Energy | Physically Active |

|---|---|---|---|

| pmTOR(Ser2448) | 23.8 ± 2.5 | 19.5 ± 3.5 | 15.8 ± 1.5 |

| mTOR | 41.9 ± 4.0 | 38.5 ± 7.8 | 32.8 ± 1.8 |

| pmTOR/mTOR | 0.57 ± 0.02 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.03† |

| pP70S6K(Thr421/Ser424) | 24.1 ± 0.8 | 20.6 ± 2.0 | 14.3 ± 0.9†† |

| P70S6K | 17.6 ± 1.6 | 22.1 ± 2.8 | 15.3 ± 1.1 |

| pP70S6K/P70S6K | 1.37 ± 0.08 | 0.93 ± 0.06†† | 0.93 ± 0.06†† |

| p4E-BP1(Thr37/46) | 15.1 ± 1.5 | 10.5 ± 0.7† | 7.7 ± 1.1†† |

| 4E-BP1 | 40.6 ± 4.3 | 36.4 ± 2.3 | 26.8 ± 3.8†† |

| p4E-BP1/4E-BP1 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.02†† | 0.29 ± 0.01†† |

The levels of proteins (relative absorbance unit x 10x4) or the ratio of phosphorylated to non phosphorylated protein are shown; values are mean ± SEM, n=7 per treatment group. The images shown in Figure 5 are those directly acquired from the ChemiDoc work station that is equipped with a CCD camera having a resolution of 1300 x 1030. The normalized intensity data from the ChemiDoc were evaluated; statistical analyses were done on the ranks of the absorbance data via multivariate analysis of variance as described in the Materials and Methods section. pmTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; pP70S6K: phosphorylated 70-kDa ribosomal protein S6 kinase; and p4E-BP1: phosphorylated eukaryote initiation factor 4E binding protein 1. Compared to sedentary control,

p<0.05.

Principal component analysis

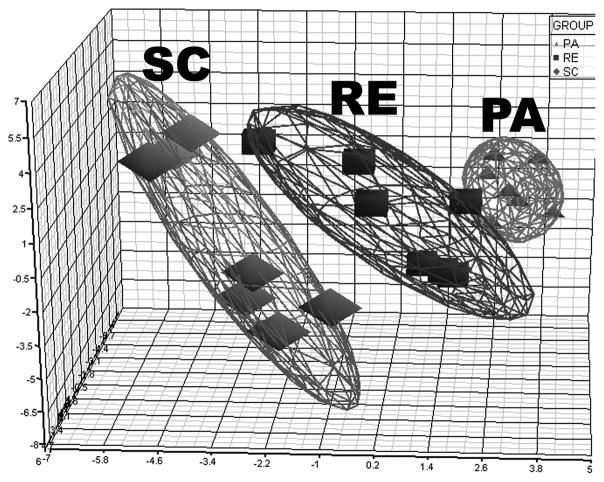

Since it can be argued that effects on the carcinogenic response, rates of cell proliferation and apoptosis and cell signaling within the induced carcinomas are to some degree interrelated, principal components analysis provides a means by which to obtain a composite view of treatment effects via multivariate analysis of those data simultaneously. As shown in Figure 6, the effects of RE and PA were distinct from SC. The cluster of points in the PA ellipsoid was more condensed than observed in either SC or RE and minimal overlap was observed in the ellipsoids for PA versus RE suggestive of both common and unique contributions of each intervention to the observed responses.

Figure 6.

Principle component analysis (PCA) of seven samples from sedentary control (SC), restricted energy (RE), or physically active (PA) group represents all of parameters for carcinogenic response, western blotting, and caspase 3 activity. Each dot represents a sample, n=7 per treatment group.

Discussion

The goal of the intervention component of this study was to have rats achieve an average amount of PA that models the national recommendation of 10,000 steps using a free wheel so that activity was at low intensity and self determined, thus modeling the daily activities of living as defined in [6]. PA behavior was maintained by food reward that was set so that body weights would differ by about 10% from physically inactive rats that ate freely, a level of restraint on energy balance that could forestall the occurrence of overweight and obesity [19]. RE rats were restricted so that each rat grew at the same rate as the PA rat to which it was paired (Figure 1). The experimental approach worked well. The average distance traveled was 7,673 m/day which is similar to the typical distance traversed when an individual walks 10,000 steps per day. The difference in weight gain between SC and either PA or RE rats was 8%. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, under these modest conditions of reduced positive energy balance, both RE and PA decreased cancer incidence and cancer multiplicity; however, only the effect of PA reached the level of statistical significance relative to SC. While the carcinogenic response was lower in PA vs. RE, those differences were not statistically significant. Keeping in mind that PA was low intensity and that moderate to high intensity PA has been reported to be necessary to inhibit breast carcinogenesis in human populations [5] and in certain animal models [20], these data hint at the existence of effects of PA that extend beyond those achieved by RE alone as suggested by the principal components analysis shown in Figure 6. However, additional experiments are required to determine if distinct effects of PA exist.

While it can be argued that the tumors induced in response to PA or RE represent failures to the lifestyle interventions, evidence from chemoprevention studies using the MNU model have shown that rates of cell proliferation and apoptosis in mammary carcinomas are predictive of the clinical efficacy of an agent in both reducing cancer risk and in affecting cancer outcomes[21]; that work also indicated that agents that induce apoptosis tend to be more effective clinically than those agents that primarily decrease cell proliferation. Since both RE and PA reduced median tumor size relative to SC (Table 1), we proceeded to determine whether the predominant effects of PA and RE were on cell proliferation or apoptosis. Consistent with our previous reports, evidence was found that RE inhibited cell proliferation by slowing transit through G1/S (Figure 2 and table 2) [13;22]; however, the predominant effect of RE was on the induction of apoptosis, measured as caspase 3 activity (Figure 3 and table 3). Induction of apoptosis appeared to be via the mitochondrial pathway. PA had the same effects on both processes; however, the magnitude was greater although the differences between RE and PA were generally not statistically significant. If additional experiments show that higher intensity PA has greater effects on carcinogenesis than RE, it will be important to determine if PA affects carcinogenesis by pathways not influenced by RE or if the magnitude of PA’s effect is simply greater than that of RE.

Since we have recently reported that one mechanism by which RE affects carcinogenesis is via suppression of mTOR activity by activation of AMP activated protein kinase and the down regulation of activated AKT [23], this hypothesis was tested. As shown in Figures and tables 4–5, both RE and PA had similar effects on AMPK and AKT and appeared to down regulate mTOR and the phosphorylation of its downstream targets. Hence, even under modest conditions of RE and PA when body weights of all rats were considered in the normal range, it appears that energy sensing pathways of which AMPK and AKT are components are responding to relatively small differences in the magnitude of energy balance that support body weights and growth curves that differ by 8% and that these effects, at least in the case of PA are inhibiting the post initiation phase of mammary carcinogenesis.

In summary, considerable evidence indicates that relatively small positive differences between energy intake and energy expenditure over a period of time predispose to the occurrence of overweight and obesity. The results of this study, in which effects on positive energy balance were at a modest level that are associated with excessive weight gain prevention, i.e. on the order of 10%, indicate that limiting energy availability via PA protected against the occurrence of experimentally induced breast cancer. While RE also reduced the carcinogenic response, the effect did not reach the level of statistical significance. Both PA and RE appeared to act via the same mechanisms, although these experiments could not exclude the possibility that differing mechanism were also involved. What is not known is whether the same finding will hold true when the intensity of PA or the extent to which positive energy balance is reduced is increased. Answers to these questions are not simply an academic exercise. Rather, because little is known about PA-cancer dose response curves, and hormetic responses to PA have been reported for other disorders, more information is needed to guide recommendations for weight control that also are associated with optimal activity in reducing risk for cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Nicholas Fernandez, Vanessa Fitzgerald, John N. McGinley, Elizabeth Neil, Andre Powell, Jennifer Price, Denise Rush, Jennifer Sells and Jay Waterman for their excellent technical assistance.

The abbreviations used are

- ACC

acetyl-CoA-carboxylase

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- Apaf-1

apoptosis protease-activating factor 1

- 4E-BP1

eukaryote initiation factor 4E binding protein 1

- hILP

human inhibitor of apoptosis protein-like protein

- IGF-1

insulin like growth factor 1

- MNU

1-methyl-1-nitrosourea

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- PA

physical activity

- PI3K

phosphoinositide kinase-3

- P70S6K

70-kDa ribosomal protein S6 kinase

- Rb

retinoblastoma

- RE

restricted energy

- SC

sedentary control

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TSC2

tuberous sclerosis 2

- XIAP

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by United States Public Health Services Grant CA100693 from the National Cancer Institute and by Grant 04B068 from the American Institute for Cancer Research.

Reference List

- 1.Kahn SE, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2006;444:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature05482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rose DP, Haffner SM, Baillargeon J. Adiposity, the metabolic syndrome, and breast cancer in African-American and white American women. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:763–777. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Gaal LF, Mertens IL, De Block CE. Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2006;444:875–880. doi: 10.1038/nature05487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson HJ, Zhu Z, Jiang W. Weight control and breast cancer prevention: are the effects of reduced energy intake equivalent to those of increased energy expenditure? J Nutr. 2004;134:3407S–3411S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3407S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.IARC. IARC Handbook of Cancer Prevention. 6. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. Weight Control and Physical Activity; pp. 1–355. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity guidelines Advisory Committee Report, 2008. US Department of Health and Human Services; Washington DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vincent HK, Taylor AG. Biomarkers and potential mechanisms of obesity-induced oxidant stress in humans. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:400–418. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeNardo DG, Coussens LM. Inflammation and breast cancer. Balancing immune response: crosstalk between adaptive and innate immune cells during breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:212. doi: 10.1186/bcr1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson HJ, McGinley JN, Rothhammer K, Singh M. Rapid induction of mammary intraductal proliferations, ductal carcinoma in situ and carcinomas by the injection of sexually immature female rats with 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:2407–2411. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.10.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson HJ. Effects of physical activity and exercise on experimentally-induced mammary carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1997;46:135–141. doi: 10.1023/a:1005912527064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman-Goetz L. Physical activity and cancer prevention: animal-tumor models. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1828–1833. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000093621.09328.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang W, Zhu Z, Thompson HJ. Effect of energy restriction on cell cycle machinery in 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea-induced mammary carcinomas in rats. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1228–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical Methods. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. Biometry the principles and practice of statistics in biological research. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochberg Y, Tamhane AC. Multiple Comparison Procedures. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrison DF. Multivariate Statistical Methods. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Co; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downey T. Analysis of a multifactor microarray study using Partek genomics solution. Methods Enzymol. 2006;411:256–270. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)11013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marinilli PA, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Tate DF, Fava JL, Wing RR. Successful Weight-loss Maintenance in Relation to Method of Weight Loss. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008 doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson HJ, Westerlind KC, Snedden J, Briggs S, Singh M. Exercise intensity dependent inhibition of 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea induced mammary carcinogenesis in female F-344 rats. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:1783–1786. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.8.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christov K, Grubbs CJ, Shilkaitis A, Juliana MM, Lubet RA. Short-term modulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis and preventive/therapeutic efficacy of various agents in a mammary cancer model. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5488–5496. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Z, Jiang W, Thompson HJ. Mechanisms by which energy restriction inhibits rat mammary carcinogenesis: in vivo effects of corticosterone on cell cycle machinery in mammary carcinomas. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1225–1231. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang W, Zhu Z, Thompson HJ. Dietary energy restriction modulates the activity of AMP-activated protein kinase, Akt, and mammalian target of rapamycin in mammary carcinomas, mammary gland, and liver. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5492–5499. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]