Abstract

Introduction

The rise in gestational diabetes (GDM), defined as first onset or diagnosis of diabetes in pregnancy, is a global problem. GDM is often associated with unhealthy diet and is a major contributor to adverse outcomes maternal and fetal outcomes. Manipulation of nutrition has the potential to prevent GDM.

Methods

We assessed the effects of nutritional manipulation in pregnancy on GDM and relevant maternal and fetal outcomes by a systematic review of the literature. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Database from inception to March 2014 without any language restrictions. Randomised controlled trials (RCT) of nutritional manipulation to prevent GDM were included. We summarised dichotomous data as relative risk (RR) and continuous data as standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

From 1761 citations, 20 RCTs (6,444 women) met the inclusion criteria. We identified the following interventions: diet-based (n = 6), mixed approach (diet and lifestyle) interventions (n = 13), and nutritional supplements (myo-inositol n = 1, diet with probiotics n = 1). Diet based interventions reduced the risk of GDM by 33% (RR 0.67; 95% CI 0.39, 1.15). Mixed approach interventions based on diet and lifestyle had no effect on GDM (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.89, 1.22). Nutritional supplements probiotics combined with diet (RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.20, 0.78) and myo-inositol (RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.16, 0.99) were assessed in one trial each and showed a beneficial effect. We observed a significant interaction between the groups based on BMI for diet-based intervention. The risk of GDM was reduced in obese and overweight pregnant women for GDM (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.18, 0.86).

Conclusions

Nutritional manipulation in pregnancy based on diet or mixed approach do not appear to reduce the risk of GDM. Nutritional supplements show potential as agents for primary prevention of GDM.

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), defined as carbohydrate intolerance first diagnosed in pregnancy, is on the rise worldwide. [1] An increase in the number of mothers entering pregnancy as obese and with advancing maternal age has contributed to this escalation in rates of GDM. Women with GDM and their children are at risk of adverse outcomes in pregnancy and in the long term. [2] About half of mothers with GDM are expected to develop Type 2 diabetes within five years after pregnancy. [3] In the offspring it is a major contributor to obesity and Type 2 diabetes in later life. [4] There is a need for safe, simple, effective and acceptable interventions that prevent the development of GDM. Such an approach has the potential to improve maternal and child health, with significant savings to the health care system.[5]

Interventions that prevent Type 2 diabetes might reduce the risk of GDM. Nutritional manipulation based on diet and lifestyle is known to significantly lower the rates of Type 2 diabetes in non-pregnant individuals. [6] This beneficial effect could be attributed either to the reduction in the calorie intake, or to the effect of individual components of diet such as yoghurt and cereals that are rich in probiotics, fibre and vitamins. [7,8] Currently no such interventions are offered to mothers as part of routine antenatal care to reduce GDM. Systematic reviews to-date, are based on limited number of studies, and have not provided conclusive evidence on the benefits of nutritional interventions in preventing GDM. [9–11] Furthermore, individual studies are underpowered to reliably estimate reductions in the rates of GDM. [12]

There is a need to collate the accruing evidence on nutritional manipulation. We systematically reviewed the effectiveness of nutritional manipulation in pregnancy with mainly diet-based interventions; mixed approach with diet and lifestyle; and nutritional supplements in preventing GDM.

Methods

We undertook the systematic review with a prospective protocol in line with current recommendations [13] and reported according to the PRISMA guidelines. [14]

This project is secondary research only so requires no ethical approval.

Literature search and study selection

A comprehensive search of the relevant literature was performed in electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library) from inception to March 2014. The search strategy was designed by combining the search terms: “diet,” “vitamins,” “probiotics,” “gestational,” “diabetes” and “pregnancy” using their word variants and Boolean operators AND and OR as appropriate. No language restrictions were applied. We contacted the authors of primary studies to obtain any relevant unpublished data. Additionally, we searched the reference lists of the included studies for relevant literature.

Studies were selected in a two-stage process. We screened the titles and abstracts against the pre-specified inclusion criteria for relevant citations. This was followed by assessment of the full texts of the selected abstracts. We included randomised studies that evaluated the effect of nutritional interventions in pregnancy: diet based advice, mixed approach (combination of diet and lifestyle including physical activity) and nutritional supplements that have the potential to reduce the risk of GDM such as vitamin-D, myo-inositol and probiotics. We did not include studies that evaluated only physical activity. The comparator was standard antenatal care. Primary prevention of GDM was the outcome of interest. The secondary outcomes were maternal and fetal complications such as pre-eclampsia, mode of delivery, gestation at delivery, birth weight of the fetus, neonatal death and neonatal intensive care unit admissions. We included studies on low risk and high-risk women. Women were classified as high risk if they have at least one of the following characteristics: obesity, previous history of GDM or fetal macrosomia, advanced maternal age, and family history of diabetes. [15] Two independent reviewers (ER and MC) selected the studies. Any discrepancy between them was resolved by a third reviewer (ST).

Study quality assessment and data extraction

Two independent reviewers (ER and MC) assessed the study quality and extracted the data using pre-designed forms. We assessed the risk of bias [16] in the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. Data were extracted in 2x2 tables for dichotomous outcomes. For continuous outcomes we extracted data on mean and standard deviation for both the groups. When more than one definition was used for GDM in a study, we extracted data for outcomes using the most recent diagnostic criteria. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion with the third reviewer (ST).

Data synthesis

Data were summarised as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for dichotomous outcomes, and standardised or weighted mean difference with 95% CI for continuous outcomes using the random effects model. We assessed statistical heterogeneity between trials by using the I2 statistic. We undertook subgroup analysis planned a priori to explore whether the effect on the outcome would vary according to the type of intervention, and Body Mass Index (BMI), and risk status of the participants for GDM. The subgroup difference was evaluated using Chi squared test. When more than one intervention was compared to standard care in a study, we chose the combined intervention over the individual diet or nutritional supplement for the pooled analysis. We used random effects model for meta-analysis. Sensitivity analysis was undertaken by substituting the individual intervention instead of the combined method to assess for any change in the summary estimates of effects. We used Harbord’s modified test to assess for publication bias [17] and potential small study effect. All analyses were performed with Review Manager (RevMan version 5.2) and Stata software (version 11).

Results

Study selection

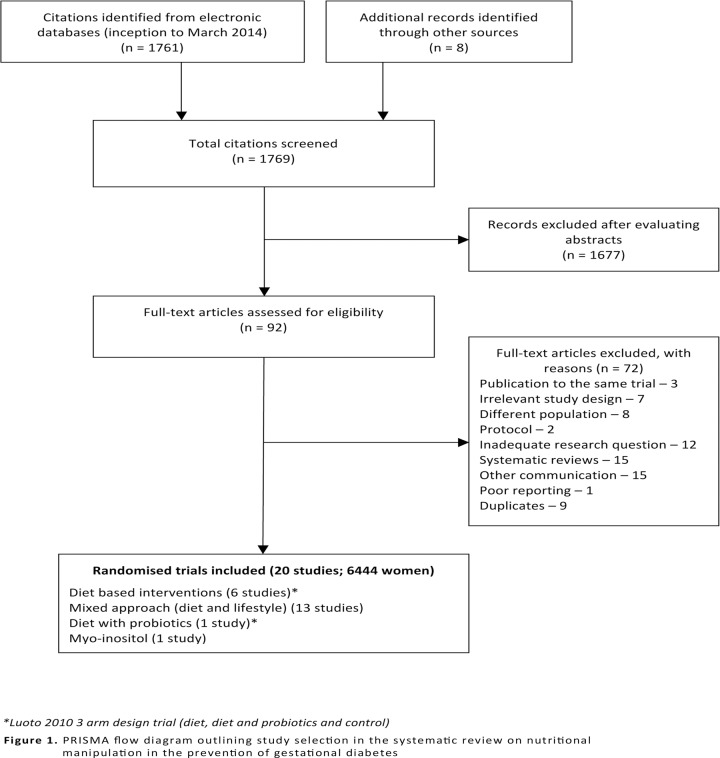

Our initial search in electronic databases yielded 1761 citations. Further eight studies were identified from the reference lists of the selected studies. Twenty RCTs with 6,444 women were included in the review. [18–37] The process of study identification and study selection is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram outlining study selection in the systematic review on nutritional manipulation in the prevention of gestational diabetes.

Characteristics of the included studies

The following nutrition based methods were evaluated: diet based interventions (5 RCTs; 1,309 women) [25,31,33,36,37], mixed (diet and lifestyle) approach (13 RCTs; 4,745 women) [18,20–24,27–30,32,34,35] and nutritional supplements: myo-inositol (1 RCT; 220 women) [19] and diet with probiotics (1 RCT; 170 women) [26] .

Of the 20 included studies, 13 RCTs were on women at risk of developing gestational diabetes [18,19,21,22,25,30–37] and seven included any risk women [20,23,24,26–29]. Twelve RCTs examined the effect of the intervention in either obese or/and overweight women [18,20,22,27,30–35,37] and eight included women of any BMI. [19,23–26,28,29,36]

The interventions varied in their composition, especially those based on diet. The diet based strategy included low glycaemic index diet [36] , and restricted energy intake according to the individual requirements. [37] The mixed approach group delivered a combination of diet and lifestyle including physical activity. The nutritional supplement myo-inositol was provided as a 2 g dose twice a day with 200 ug folic acid. The probiotics Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG and Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 in dose of 1010 colony forming units were taken every day in addition to intensive dietary counselling. [26]

The interventions were delivered in groups or as a one-to-one contact session, and often in more than one step. The nutritional advice was accompanied by psychological input in some studies. [23,31] Participants were provided with food diaries to record their food intake and the dieticians tailored the intervention according to the caloric requirements. Most of the interventions from the mixed approach category were based on the national recommendations on healthy eating in pregnancy, with additional input provided by trained healthcare personnel. The mixed approach category aggregates studies with complex interventions targeting weight gain from different angles; ranging from change in a type of consumed foods and daily physical activity pattern [23,27] , behavioural change [18,22] to weight gain monitoring only [24] . All the interventions were commenced before 28 weeks at varied time points in the first or second trimester.

The definition of GDM varied between the studies (Table 1). The following maternal outcomes were evaluated: preterm delivery, caesarean section, induction of labour, pre-eclampsia and pregnancy induced hypertension. The fetal outcomes included birth weight, shoulder dystocia and admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The follow up period varied from 6 weeks after delivery to the end of exclusive breastfeeding.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of included studies evaluating the effectiveness of nutrition manipulation in primary prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

| Study, Year | Number of patient | Methods | Participants | Intervention | Control | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luoto 2010 26 | 256 | Methods of Randomization: Random assignment to one of three groups according to computer-generation block of six women | Inclusion Criteria: Women in their early pregnancy with no chronic metabolic diseases | Group 1: Intensive dietary counselling | Dietary counselling according to a national programme and placebo capsules | GDM (Definition: Fourth International Workshop-Conference on GDM ≥ 4·8 mmol/l at baseline, or ≥10·0 mmol/l at 1 h, ≥8·7 mmol/l at 2 h.) |

| Allocation concealment: Sealed envelopes with subject number | Exclusion Criteria: Not specified | Group 2: Probiotic capsules Lactobacillus, Rhamnosus GG and Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 at a dose of 1010 colony forming units day each before 17 weeks of gestation once a day | caesarean section, birth weight, gestational age at delivery | |||

| Blinding: Double blind manner. All personnel involved in handling or analyzing blood samples was blinded to the intervention | ||||||

| D’Anna 2013 19 | 220 | Methods of Randomization: A computer randomization with 1:1 allocation | Inclusion Criteria: Caucasian women with singleton pregnancy without GDM whose first degree relative was affected by type-2 diabetes; whose BMI<30kg/m2; fasting plasma glucose <126mg/dl and random glycaemia <200mg/dl. | 2g myo-inositol plus 200ug acid folic twice a day since 12–13 weeks of gestation | 200ug acid folic twice a day since 12–13 weeks of gestation. | GDM (Definition: ADIPS criteria—75 g, 2 hours glucose tolerance test, with cutoff values of >92 mg/dl for time 0, >180 mg/dl after 1 hour, >153 mg/dl after 2 hours. At least one of three values over or equal to the cutoff was enough for diagnosis of GDM) |

| Allocation concealment: Not reported | Exclusion Criteria: Pre-pregnancy BMI>30kg/m2, previous GDM, pre-gestational diabetes, first trimester glycosuria, first degree relative not affected by type2 diabetes, fasting plasma glucose >126mg/dl or random glycaemia >200mg/dl, Twin pregnancy, any therapy using corticoids, Not Caucasian or with PCOS | gestational hypertension, preterm delivery, caesarean section, | ||||

| Blinding: Open Label Trial | macrosomia, respiratory distress syndrome, shoulder dystocia, neonatal hypoglycemia. | |||||

| Korpi-Hyovalti 2012 25 | 54 | Methods of Randomization: A computed randomization | Inclusion Criteria: Meeting one of the following criteria: BMI >25, previous history of GDM, previous macrosomia (>4,500g),>40 years, family history of diabetes, venous plasma glucose concentration after 12 h overnight fasting was 4,8 to 5,5mmol/l 2h oral glucose tolerance test plasma <7,8 | Diet: rich in vegetables, berries and fruits, fat-free and low-fat dairy products, low-fat meat, soft margarines and vegetable oils and whole-grain products. Recommended energy intake: normal weight women—126 kJ/kg per day; overweight women—105 kJ/kg per day. The goal of in pregnancy weight gain: 12·5–18 kg for underweight women, 11·5–16·0 kg for normal-weight women and 7–11·5 kg for overweight women. | General information on diet and physical activity in a single session to decrease the risk of GDM | GDM (Definition: Not reported) |

| Allocation Concealment: Not reported | ||||||

| Blinding: Open Label Trial | Exclusion Criteria: Diagnosed GDM at inclusion | birth weight, gestational age at delivery | ||||

| Quinvilan 2011 31 | 132 | Methods of Randomization: A computer randomization. | Inclusion Criteria: Pregnant women carrying fetus without any known anomalies; able to attend hospital for antenatal care; underweight or obese according to standard BMI ranges | Four step multidisciplinary antenatal care: continuity of care provider, weighing on arrival, brief dietary intervention by food technologist at every antenatal visit and psychological assessment and intervention if indicated | Routine public antenatal care | GDM (Definition: Women underwent on consecutive days, a 75g fasting 2-hours glucose tolerance test and then 100g fasting 3-hours glucose tolerance. > 6.6 mmol/l decreased gestational glucose tolerance >7.7 mmol/l GDM) |

| Allocation concealment: Sealed opaque envelopes | GWG | |||||

| Blinding: Outcomes data were audited by a nurse blinded to randomization status | Exclusion Criteria: Multiple gestations. | birth weight | ||||

| Thornton 2009 33 | 257 | Methods of Randomization: A random-number tables | Inclusion Criteria: Pregnant with a single fetus between 12–28 weeks of gestation. BMI≥30kg/m2 | The nutritional programme with dietary guidelines similar to ones used for patients with GDM. All women were asked to record in a diary all the foods and beverages consumed during each day | Standard Care | GDM (Definition: Not reported) |

| Allocation concealment: Sequentially numbered envelopes | GWG, pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension, duration of pregnancy, induction of labour, caesarean Section | |||||

| Blinding: Not reported | Exclusion Criteria: Patient with pre-existence diabetes, hypertension or chronic renal disease | birth weight, macorosomia, Apgar | ||||

| Walsh 2012 36 | 800 | Methods of Randomization: A computer generated allocations in ratio 1:1 | Inclusion Criteria: Women who had previously delivered a macrosomic baby (>4kg). | Health eating guidelines for pregnancy with focus on low glycaemic index | Routine Antenatal Control | GDM (Definition: Carpenter and Coustan /ADA) |

| Allocation concealment: Sealed opaque envelopes | Exclusion Criteria: Women with any underlying medical disorder, including a previous history of gestational diabetes; gestation beyond 18 weeks and multiple pregnancy | Maternal glucose intolerance, duration of pregnancy, mode of delivery, anal sphincter injuries, weight gain in recommendation to IOM, postpartum haemorrhage, | ||||

| Blinding: According to the authors blinded randomized trial of diet intervention is not possible | birth weight, shoulder dystocia | |||||

| Wolff 2008 37 | 53 | Methods of Randomization: A computerized randomization | Inclusion Criteria: Pregnant obese women with BMI >30kg/m2, in their early pregnancy (<15weeks) of Caucasian origin | 10 consultations 1 hour each with a trained dietitian during the pregnancy. A healthy diet according to the official Danish dietary recommendations. The energy intake was restricted based in individually estimated energy requirement and estimated energetic cost of fetal growth | No consultations with dietitian and no energy intake or gestational weight gain restrictions | GDM (Definition: Not reported) |

| Allocation concealment: Not reported | Exclusion Criteria: Smoking, below 18 and above 45 years, with multiple pregnancy, known medical complication which could affect fetal growth adversely or contraindicate limitation to weight gain | fasting blood samples for measurements of serum insulin, serum leptin, and blood glucose, GWG, daily food intake, fasting bloods samples for measurement of insulin, leptin and blood glucose, prolonged pregnancy, cesarean section, pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension, | ||||

| Blinding: The physicians and midwives were blinded in regard to the treatment assignment; the women were asked not to reveal the allocation by the randomization | birth weight, Apgar score, infant length at delivery, placental weight | |||||

| Bogaerts 2012 18 | 141 | Methods of Randomization: Randomization took place by choosing one opaque envelope containing a ticket indicating one of the three groups | Inclusion Criteria: Obese pregnant women (BMI >29kg/m2) attending the antenatal clinic before 15 weeks pregnancy were informed by their gynecologist or midwife about the study. | The four sessions were scheduled: The sessions focused on the relation between energy intake and energy expenditure based on the active and healthy food pyramid for pregnant women. Recommendations for a healthy and balanced diet were based on the official National Dietary Recommendations and consisted of 50–55% carbohydrate intake, 30–35% fat intake and 9–11% protein energy intake. | Routine antenatal care | GDM (Definition: ADIPS criteria) |

| Allocation Concealment: Opaque envelopes | Exclusion Criteria: Gestational age >15 weeks, Pre-existing type 1 diabetes, multiple pregnancy, primary need for nutritional advice and insufficient knowledge of the Dutch language. | GWG, gestational age at delivery, gestational hypertension / pre-eclampsia, levels of state anxiety mood depression | ||||

| Blinding: Not reported | birth weight, induction of labour, caesarean section | |||||

| Dodd 2014 20 | 2212 | Methods of Randomization: The computer generated randomization schedule with balanced variable blocks in the ratio 1:1 prepared by third party | Inclusion Criteria: BMI ≥25kg/m2 and singleton pregnancy between 10 to 20 weeks’ gestation | Dietary advice consistent with current Australian standards (maintenance of balance between carbohydrates, fat, and protein; reduction in intake of foods high in refined carbohydrates and saturated fats; increase of fiber intake. Physical activity advice primarily aiming women to increase their amount of walking and incidental activity | Standard care according to state-wide perinatal practice and local hospital guidelines which did not covered routine provision of advice related to diet, exercise, or gestational weight gain | GDM (Definition: positive 75g oral glucose tolerance test result with fasting blood glucose ≥5.5 mmol/L or 2 hour ≥7.8 mmol/L) |

| Allocation Concealment: Allocation revealed using telephone central randomization service | Exclusion Criteria: Women with type 1 or 2 diabetes diagnosed before pregnancy | GWG, cesarean section, preterm delivery, gestational hypertension,, induction of labour, | ||||

| Blinding: Outcome assessors were blinded to the treatment group allocated | shoulder dystocia, neonatal death, admission to NICU | |||||

| Guelinckx 2010 21 | 130 | Methods of Randomization: Random allocation by using block randomization | Inclusion Criteria: Obese (BMI >29 kg/m2) white women attending prenatal clinic before 15 weeks of gestation | Recommendation on balanced, healthy diet following official National Dietary Recommendations | Routine prenatal care | GDM (Definition: Carpenter and Coustan criteria) |

| Allocation Concealment: Not reported. | Exclusion Criteria: Pre-existing diabetes or developing GDM, multiple pregnancy, recruitment after 15 weeks of gestational age, premature labor (<37 weeks of gestation), primary need for nutritional advice in case of a metabolic disorder, kidney problems, Crohn disease, and any allergic conditions. | GWG, gestational age at delivery, gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, induction of labour, caesarean section, | ||||

| Blinding: Not reported. | birth weight | |||||

| Harrison 2011 22 | 228 | Methods of Randomization: Computer-generated randomized sequencing | Inclusion Criteria:12 to 15 weeks gestation, overweight (BMI ≥ 25 or ≥ 23kg/m2 if high-risk ethnicity [Polynesia, Asia, and Africa populations]) or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), and at increased risk for developing GDM identified by a validated risk prediction tool | Four-session behavior change lifestyle intervention based on the Social Cognitive Theory (adapted from HeLP-her program) The sessions provided comprised of information of pregnancy-specific dietary advice, simple healthy eating and physical activity messages and simple behavioral change strategies. | A brief, single education session based on Australian Dietary and Physical Activity Guidelines. | GDM (Definition: ADIPS criteria including the presence of either a fasting venous plasma glucose level of ≥99 mg/dl (≥5.5 mmol/l) and/or a 2-h level of ≥144 mg/dl (≥8.0 mmol/l); and International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group (IADPSG) criteria—fasting venous plasma glucose level of ≥91.8 mg/dl (≥5.1 mmol/l), a 1-h plasma glucose of ≥180 mg/dl (≥10.0 mmol/l), or a 2-h glucose level of ≥153 mg/dl (≥8.5 mmol/l) |

| Allocation Concealment: Sealed opaque envelopes | Exclusion Criteria: Multiple pregnancies, diagnosed type 1 or 2 diabetes, BMI ≥ 45 kg/m2, and pre-existing chronic medical conditions | GWG, physical activity, risk perception | ||||

| Blinding: Care providers, investigators and outcome data analyzers were blinded to group allocation | ||||||

| Hui 2011 23 | 224 | Methods of Randomization: A computer-generated randomization table | Inclusion Criteria: Pregnant women (<26 weeks of pregnancy) with no pre-existing. | Diet: a personalized plan with recommendations on food choice, portion size, frequency of eating and pattern of intake Physical activity advice: Exercise 3–5 times per week (30–45 min per session) Among recommended were: walking, swimming, mild aerobics, stretching and strength exercise. Additionally participants received exercise instruction (VHS/DVD) to facilitate home-based exercise | Standard prenatal care recommended by the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada24 Package of up-to-date information on physical activity and nutrition healthy pregnancy from the Health Canada | GDM (Definition: Canadian Diabetes Association’s clinical practice guidelines). |

| Allocation Concealment: Sealed envelopes | Exclusion Criteria: Any medical, obstetric, skeletal or muscular disorders that could prevent women from taking part in physical exercise | excessive gestational weight gain (EGWG) | ||||

| Blinding: Participants and study staff were not blinded to the intervention | birth weight, macrosomia | |||||

| Jeffries 2009 24 | 286 | Methods of Randomization: Computer generated | Inclusion Criteria: Before 14 weeks of gestation | Given an optimal gestational weight gain range | Standard antenatal care | GDM (Definition: Not reported). |

| Allocation Concealment: Opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes. | Exclusion Criteria:<18 years or >45 years, Type I or II diabetes, multiple pregnancies | preterm delivery, gestational age at delivery, pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension, cesarean section | ||||

| Blinding: Participants were blinded to the purpose of the study | birth weight, shoulder dystocia | |||||

| Petrella 2013 27 | 66 | Methods of Randomization: A computer-generated random allocation in blocks of three | Inclusion Criteria: Pre-pregnancy BMI≥25 kg/m2, age 418 years and single pregnancy. | The Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes group diet: 1500 kcal/day; three main meals and three snacks. In case of increased physical activity program, the dietitian added an amount of 200 kcal/day for obese or 300 kcal/day for overweight women. | A simple nutritional booklet about for a healthy diet during pregnancy lifestyle, in agreement with Italian Guidelines. | GDM (Definition: ADA criteria) |

| Allocation Concealment: Sealed in numbered white envelopes | Exclusion Criteria: Twin pregnancy, chronic diseases (i.e. diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension, untreated thyroid diseases), GDM in previous pregnancies, smoking during pregnancy, previous bariatric surgery, women who just engaged in regular physical activity, dietary supplements or herbal products known to affect body weight, other medical conditions that might affect body weight, and plans to deliver outside our Birth Center | GWG, gestational age at delivery, Preterm Delivery. Gestational hypertension. Caesarean Section. Induction of labour. | ||||

| Blinding: Both gynecologist and dietitian knew the allocation of the patient | birth weight, admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit | |||||

| Phelan 2011 28 | 401 | Methods of Randomization: Randomization was computer-generated | Inclusion Criteria: Gestational age 10–16 weeks, BMI 19.8–40 kg/m2, nonsmoking, adults (aged.18 y), access to a telephone, and a singleton pregnancy | Standard care and a behavioral lifestyle intervention designed to prevent excessive weight gains during pregnancy. IOM guidelines for nutrition and weight during pregnancy and was designed with an eventual dissemination in mind. | Standard nutrition counseling | GDM (Definition: Not reported) |

| Allocation Concealment: Opaque envelopes | Exclusion Criteria: Major health or psychiatric diseases, weight loss during pregnancy, or a history of 3 miscarriages | Excessive Gestational Weight Gain (EGWG), gestational hypertension/ pre-eclampsia, cesarean section, preterm delivery, gestational age at delivery, birth weight | ||||

| Blinding: Clinic staff and physicians were blinded to subject randomization | ||||||

| Polley 2002 29 | 120 | Methods of Randomization: Not reported | Inclusion criteria: Pregnant women, <20 weeks gestation, | Information (written and oral) in the following areas: (a) appropriate weight gain during pregnancy; (b) exercise during pregnancy; and (c) healthful eating during pregnancy | Standard prenatal care (standard nutrition counselling which emphasized a well-balanced dietary intake and advice to take a multivitamin Iron supplement) | GDM (Definition: Not reported) |

| Allocation Concealment: Not reported | Exclusion criteria: Women younger than 18 years, underweight (BMI <19.8 kg/m2), >12 weeks gestation, high risk pregnancy (drug abuse, chronic health problems, previous complication during pregnancy or current multiple gestation) | Excessive Gestational Weight Gain (EGWG) Gestation age at delivery, preterm delivery (<36 weeks), cesarean delivery, pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension | ||||

| Blinding: Not reported | birth weight, macrosomia (>4000 g), | |||||

| Poston 2013 30 (pilot study) | 183 | Methods of Randomization: Web based | Inclusion Criteria: BMI > 30kg/m2, singleton pregnancy, gestational age >15 weeks and <17 weeks gestation. | Dietary advice: increased consumption of low GI foods; replacement of sugar sweetened beverages with low GI alternatives; reduction of intake of saturated fats by their replacement with monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. Physical activity advice: walking at a moderate intensity level | Routine antenatal care (diet and physical activity advice in accordance with local policies, based on NICE guidelines (UK)) | GDM (Definition: Diagnosis was confirmed by fasting glucose > 5.1 mmol/L and or 1hr glucose > 10 mmol/L and or 2 hr glucose > 8.5 mmol/L according the International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups guidelines. |

| Allocation Concealment: Treatment allocation was done automatically using web based tool | Exclusion criteria: Gestation age <15 or >17,6 weeks; pre-existing diabetes; pre-existing essential hypertension (treated); pre-existing renal disease; multiple pregnancy; systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); anti-phospholipid syndrome; sickle cell disease; thalassemia; celiac disease; currently prescribed metformin; thyroid disease or current psychosis. | GWG, pre-eclampsia, mode of delivery | ||||

| Blinding: Not reported | large for gestational age (LGA) | |||||

| Renault 2013 32 | 283 | Methods of Randomization: Web based randomization | Inclusion Criteria: Pre-pregnancy BMI ≥30 kg/m2, Before 16 weeks of gestation. Age older than 18 years. Singleton pregnancy. Normal scan at 11–14 weeks. Read and speak Danish | The dietary intervention: consultation with dietitian every 2 weeks, (outpatient visits and phone contacts) Physical activity monitored using validated pedometer counting the daily numbers of steps | Usual hospital standard regimen for obese pregnant women | GDM (Definition: 75g glucose 2 hs) |

| Allocation Concealment: Web based allocation run by a third party | Exclusion Criteria: Multiple pregnancy, diabetes, any other serious diseases limiting physical activity, bariatric surgery, Alcohol or drugs abuse. | GWG, gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, induction of labour, caesarean section, gestational age at delivery, preterm delivery | ||||

| Blinding: Not reported | birth weight | |||||

| Vesco 2013 34 (Conference Abstract) | 114 | Methods of Randomization: Using a computerized algorithm to generate the random assignments | Inclusion Criteria: Women with singleton gestation and a pre-pregnancy BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | A weekly, group-based, weight management intervention designed to help limit GWG to 3% of weight (measured at the time of randomization) | Usual care | GDM (Definition: ADA criteria) |

| Allocation Concealment: Not Reported | Exclusion Criteria: Gestational age >20 weeks, multiple pregnancy, anticipated disenrollment from KPNW prior to delivery, type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (or a diagnosis of GDM prior to randomisation), other medical conditions requiring specialized medical care or conditions potentially affecting weight gain | GWG, gestational age at delivery, delivery type, cesarean section, preterm delivery, gestational hypertension/ pre-eclampsia | ||||

| Blinding: Clinical staff members were blinded to group assignment | birth weight, large for gestational age (LGA), small for gestational age (SGA) | |||||

| Vinter 2011 35 | 360 | Methods of Randomization: Computer-generated table of numbers | Inclusion Criteria: Pre- or early pregnancy BMI of 30–45 kg/m2, age 18–40 years, 10–14 weeks of gestation | Dietary counselling following official Danish recommendations aiming to limit GWG to 5 kg Moderately physically active (30–60 min daily) monitored using a pedometer. Indoor training consisting of aerobic with light weights and elastic bands, and balance exercises | Access advice about dietary habits and physical activities in pregnancy without any additional intervention | GDM (Definition: 2-h oral glucose tolerance test capillary blood glucose result was > or = 9 mmol/L). |

| Allocation Concealment: Closed envelopes | Exclusion Criteria: Prior serious obstetrics complications, chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes), positive OGTT in early pregnancy, Alcohol or drugs abuse, multiple pregnancy | GWG, pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension. cesarean section, | ||||

| Blinding: Not reported | macrosomia, large for gestational age (LGA), admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. |

GDM—gestational diabetes mellitus; GWG—Gestational Weight Gain; ADIPS—the Australian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society; ADA—according to the American Diabetes Association;

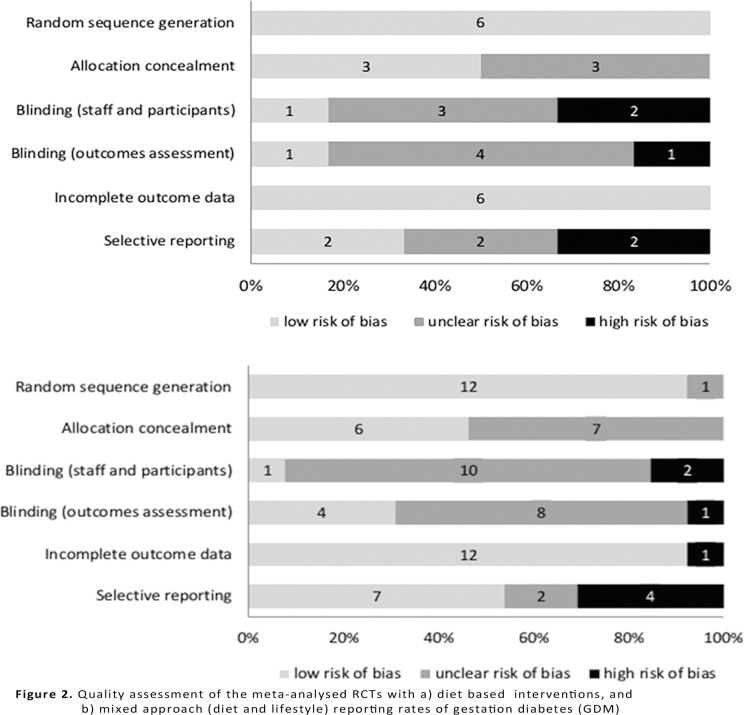

Quality of the included studies

All studies with diet based interventions had low risk of bias for adequate randomisation and attrition [25,26,31,33,36,37] ; half of them (3/6) had low risk for allocation concealment [26,31,36] . Only one study reported adequate blinding of researchers and participants [26] and 33% were considered as high risk in this domain (2/6) [25,36] . The blinding of outcomes assessors was adequate in one diet study [31] and inadequate in one [25] . The risk of bias due to selective reporting was low in 33% of the included diet based studies (2/6) [26,31] and inadequate in other two trials [25,36] .

Twelve trials on mixed (diet and lifestyle) approach had a low risk of bias for adequate randomisation (92%, 12/13). [18,20–24,27,28,30,32,34,35] Allocation concealment was well described in six [20,22,27,28,30,32] out of 13 mixed approach interventions studies. Blinding of staff and participants was adequate in one trial [22] and inadequate in two; and blinding of outcomes assessment was correct in 31% of included trials (4/13) [20,22,28,34]. Attrition bias was low for majority of studies except one study that was at high risk [23]. Selective reporting bias was low in 54% of mixed approach trials [18,20,22–24,28,29] and was considered to be high in four trials (31%) [21,27,32,35].

Of the two trials on nutritional supplements, the trial on myo-inositol supplementation [19] was assessed to have low risk of bias for adequate randomisation, attrition and selective reporting and high risk for blinding of staff and participants. The trial on probiotics had low risk of bias for all domains except for detection bias. [26] Fig. 2 provides the quality assessment of the included studies for diet based and mixed approach groups.

Fig 2. Quality assessment of the meta-analysed RCTs with a) diet based interventions, and b) mixed approach (diet and lifestyle) reporting rates of gestation diabetes (GDM).

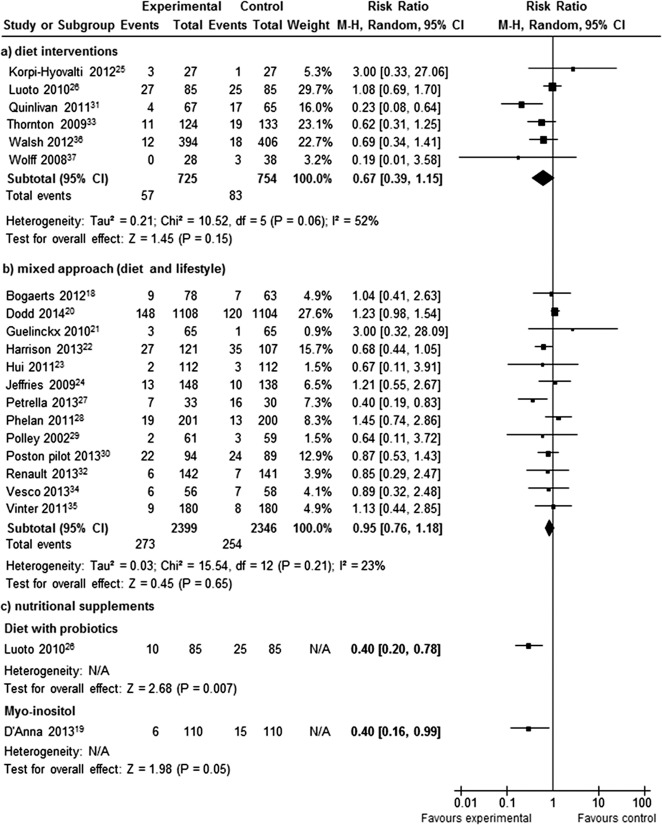

Effect of nutritional manipulation on GDM

Interventions that were mainly based on diet reduced the rates of GDM by 33% (RR 0.67; 95% CI 0.39, 1.15I2 = 52%) (Fig. 3a). There were no differences between the two groups for mixed (diet and lifestyle) approach (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.89, 1.22; I2 = 23%) (Fig. 3b). The risk of GDM was reduced by 60% for probiotics (with diet) in comparison to standard care (RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.20, 0.78; p<0.01). A similar reduction was observed for the nutritional supplement myo-inositol (RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.16, 0.99; p = 0.05) (Fig. 3c).

Fig 3. Forest plot of the meta-analysed RCTs with a) diet interventions, b) mixed approach (diet and lifestyle), and c) nutritional supplements reporting rates of gestation diabetes (GDM).

Small study effect

Due to insufficient number of studies for myo-inositol and diet with probiotic supplementation we examined funnel plot asymmetry only for diet based and mixed approach groups. For both groups Harbord’s statistical tests for small study effect was insignificant (p = 0.87 and p = 0.21, respectively),

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup comparison was possible to conduct only for two intervention categories: diet based and mixed approach. There was no subgroup differences based on maternal risk for GDM for both intervention groups and for BMI category comparison for the mixed approach group (Table 2). There was a significant difference according to the BMI for diet based intervention (p = 0.04). A significant reduction in GDM was observed in the subgroup comprised of obese and overweight women (RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.18, 0.86, I2 = 29%).

Table 2. Subgroup analyses for intervention types and clinical characteristics for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in evaluation of nutritional manipulation in pregnancy.

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | No of studies | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | P value for interaction |

| Diet based interventions | |||

| Risk status | |||

| High risk | 525,31,33,36,37 | 0.55 (0.30, 1.00) | 0.08 |

| Low risk | 126 | 0.40 (0.20, 7.80) | |

| BMI category | |||

| Obese and overweight | 331,33,37 | 0.40 (0.18, 0.86) | 0.04 |

| Any weight | 325, 26,36 | 0.98 (0.65, 1.47) | |

| Mixed approach (diet and lifestyle) | |||

| Risk status | |||

| High risk | 718,21,22,30,32,34,35 | 0.83 (0.64, 1.09) | 0.19 |

| Low risk | 620,23,24,27–29 | 0.97 (0.64, 1.48) | |

| BMI category | |||

| Obese and overweight | 918,20–22,27,30,32,34,35 | 1.02 (0.86, 1.20) | 0.44 |

| Any weight | 423,24,28,29 | 1.20 (0.75, 1.93) | |

Effect of nutritional interventions on other maternal and neonatal outcomes

Maternal outcomes

Eleven trials [19,20,22,24,27–29,32–34,36] evaluated the role of interventions in preventing preterm delivery before 37 weeks of gestation None of the interventions significantly reduced the rate of preterm deliveries; however, the risk reduction was the highest (51%) for diet based group (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.19, 1.29).

Fourteen RCTs [18–20,23,24,26–29,32–36] reported the effect of interventions on the caesarean section rate and six studies [18,20,27,32,33,36] on the rate of the induction of labour. There was no significant effect of the intervention on the rates of evaluated outcomes (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of findings for maternal and neonatal outcomes from trials with nutritional manipulation in pregnancy.

| Outcome | Intervention | No of studies | Sample size | Risk Ratio* (95% CI) | I2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal outcomes | ||||||

| Preterm delivery (< 37weeks) | Diet based interventions | 233,36 | 1,057 | 0.49 (0.19, 1.29) | 0% | 0.15 |

| Mixed approach | 820,22,24,27–29,32,34 | 3,697 | 0.84 (0.55, 1.27) | 27% | 0.40 | |

| Myo-inositol | 119 | 220 | 0.75 (0.17, 3.27) | N/A | 0.70 | |

| Caesarean section | Diet based interventions | 326,33,37 | 494 | 1.17 (0.99, 1.38) | 0% | 0.06 |

| Mixed approach | 1018,20,23,24,27–29,32,34,35 | 4,194 | 0.91 (0.82, 1.02) | 7% | 0.10 | |

| Myo-inositol | 119 | 220 | 0.98 (0.70, 1.36) | N/A | 0.89 | |

| Diet with probiotics | 126 | 170 | 1.09 (0.51, 2.33) | N/A | 0.82 | |

| Induction of labour | Diet based interventions | 233,36 | 1,057 | 1.14 (0.54, 2.40) | 83% | 0.74 |

| Mixed approach | 418,20,27,32 | 2,689 | 1.02 (0.91, 1.13) | 0% | 0.78 | |

| Gestational hypertension | Diet based interventions | 233,37 | 323 | 0.16 (0.02, 1.11) | 19% | 0.06 |

| Mixed approach | 718,20,24,27,-29,32 | 3,496 | 0.93 (0.68, 1.26) | 17% | 0.63 | |

| Myo-inositol | 119 | 220 | 1.50 (0.26, 8.80) | N/A | 0.65 | |

| Pre-eclampsia | Diet based interventions | 233,36 | 323 | 0.66 (0.27, 1.59) | 0% | 0.36 |

| Mixed approach | 718,20,24,28,29,32,35 | 3,793 | 0.96 (0.75, 1.24) | 0% | 0.77 | |

| Fetal outcomes | ||||||

| Birth weight | Diet based interventions | 525,31,33,36,37 | 1,219 | 0.06 # (-0.13, 0.25) | 46% | 0.53 |

| Mixed approach | 618,23,24,27,28,34 | 1,088 | 0.04 # (-0.17, 0.24) | 65% | 0.73 | |

| Myo-inositol | 119 | 220 | -0.51 # (-0.79, -0.22) | N/A | <0.01 | |

| Shoulder dystocia | Diet based interventions | 136 | 800 | 0.52 (0.09, 2.80) | N/A | 0.44 |

| Mixed approach | 220,24 | 2,506 | 1.24 (0.81, 1.91) | 0% | 0.33 | |

| Myo-inositol | 119 | 220 | 0.50 (0.05, 5.43) | N/A | 0.57 | |

| Admission to NICU | Mixed approach | 220,35 | 2,562 | 1.01 (0.91, 1.13) | 0% | 0.82 |

| Neonatal death | Mixed approach | 120 | 2,212 | 3.99 (0.45, 35.60) | N/A | 0.22 |

| Stillbirth | Mixed approach | 120 | 2,212 | 1.00 (0.29, 3.43) | N/A | 1.00 |

*Random effect model

# SMD—standardized mean difference

Ten studies reported on the effects of the intervention on gestational hypertension [18–20,24,27–29,32,33,37] and nine on pre-eclampsia [18,20,24,28,29,32,33,35,37]. The risk of gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia was reduced by 84% and 34%, respectively, in diet-based group (Table 3). There was no noticeable effect of mixed approach on the occurrence of discussed outcomes.

Fetal outcomes

Ten trials evaluated the effect of nutritional manipulation in pregnancy on the birth weight of the newborns. [18,19,23–25,27,28,31,33,34,36,37] The only significant difference in birth weight between the groups was recorded for myo-inositol (SMD-0.51, 95% CI-0.79, -0.22; p<0.01). Four trials [19,20,24,36] reported on shoulder dystocia, and showed no significant difference between the groups for any of three intervention groups (Table 3).

In two studies evaluating mixed approach (2,562 women) authors reported the rates of the admissions to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. [20,35] There was no statistically significant difference in numbers of admissions between the intervention and the control group (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.91, 1.13; I2 = 0%). Only one study [20] reported events of neonatal death and stillbirth. For both outcomes estimated risks were none significant (Table 3).

Adverse effects

Nine of the 20 trials reported or evaluated the adverse effects of the interventions on the mother and offspring. [19,23,26,28,29,31,33,36,37] No significant adverse effects were observed for myo-inositol or probiotics in studies that exposed women to the intervention in the first trimester. One study [31], assessed the impact of the diet based intervention and reported a case of severe intrauterine growth restriction in each of the arms that resulted in preterm delivery.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Nutritional manipulation based on diet or mixed approach does not appear to prevent GDM. There was a trend towards beneficial effect in women on mainly diet-based intervention, with a potential for significant reduction in GDM risk when limited to obese and overweight women. Nutritional supplements such as probiotics and myo-inositol show promising role in the strategy for primary prevention of GDM.

Relevance to current evidence

Until now, there has been no robust evidence to provide guidance on the primary prevention of GDM due to the small number of studies limited to few interventions in published reviews. [38] The number of eligible studies has doubled since our previous review that evaluated the effect of mixed approach (diet and lifestyle modification) on GDM. [11] By evaluating all the relevant interventions, our review is the first to systematically assess the effects of nutritional manipulation in pregnancy on GDM. We complied with current guidelines and used a comprehensive search strategy without any language restrictions. By including only randomised trials, we avoided some of the pitfalls encountered by earlier reviews that included quasi-randomised studies [10] and women with GDM [9].

Effects of interventions on GDM

Amongst evaluated interventions, diet based interventions appear to show potential for preventing GDM. This could be due to the following reasons: individual dietary and components; change in gestational weight gain and effect of nutritional supplements.

The interventions promoted the uptake of healthy components such as fibre, probiotics and food rich in vitamins such as myo-inositol that may have an additive effect in reducing the concentrations of maternal glucose. [19,26] The women in the intervention group had reduced total energy intake and glycaemic load compared to the controlled group. [30,36] Low glycaemic index diet attenuates the increase in insulin resistance observed in pregnancy, thereby reducing the risk of GDM. [39] The risk of GDM is known to be reduced by a quarter with each 10-g/day increment in total fibre intake. [40] The largest benefit with diet was observed where there was a multidisciplinary input into the intervention, with the use of food diaries [31] and feedback methods.

Diet based interventions have also shown the greatest reduction in gestational weight gain compared to other methods. [11] The reduction in gestational weight gain may have influenced the fall in the rates of GDM. [11] Serum leptin, a known factor associated with GDM [41], was lowered by 20% with reduced gestational weight gain. [37] Cord leptin concentrations were also increased in newborns born to mothers with diabetes. [42]

We did not observe the beneficial effect in the subgroup with mixed approach that combined diet and physical activity. This is consistent with previously published reviews that did not show beneficial effect of physical activity in pregnancy on pregnancy outcomes. [11,43] Rather than physical activity failing to have an expected impact on GDM, it is likely that women in the intervention group had poor compliance with the intervention. Objective assessments with methods such as accelerometry have shown no difference in the physical activity between the two groups. [30] The largest trial on mixed approach (diet and lifestyle) in pregnancy, the LIMIT study failed to show a benefit with the intervention for GDM and other maternal outcomes including gestational weight gain.[20] Non-compliance with the intervention, with a quarter of women not attending the required two sessions with the dietician could have contributed to the lack of benefit.

Simple interventions based on nutritional supplements such as myo-inositol and probiotics appear to have significant potential in preventing GDM. Inositol is available in cereals, meat, fresh fruit and vegetables, corn and legumes. The average dietary intake contains 1g of inositol/day. Myo-inositol is known to increase the sensitivity to insulin, [44] a possible mechanism for the observed reduction in GDM.

Other supplements such as the probiotics, consisting of microorganisms of beneficial nature, appear to reduce the risk of GDM when combined with a dietary intervention. [26] By altering the gut microbiome, and by modifying the concentration of plasma lipopolysaccharides, probiotics alter the inflammatory pathways and sensitivity to insulin. It is possible that the benefit observed in the Luoto trial in reducing GDM [26] was due to a synergistic action between a diet rich in probiotics in addition to probiotics supplements.

Safety of the interventions

Any intervention evaluated in pregnancy needs to pass a rigorous evaluation of its safety to the mother and baby. Our previous detailed evaluation of diet and mixed interventions in pregnancy did not find adverse effects to the mother or baby, except in extreme conditions such as starvation. [11] Although theoretical concerns have been raised regarding the risk of preterm delivery with inositol, this was not observed in both randomised and observational studies on inositol in pregnancy. Inositol use in early pregnancy may in an additional beneficial role, by preventing the risk of neural tube defect in folate resistant mothers. [45]

Limitations

Our findings were limited by differences in the inclusion criteria of the studies, variation in the components of the intervention such as duration, intensity and frequency, non-standardised care in the control group and non-uniform definitions of GDM. Furthermore, women in the intervention group had more than one intervention, such as diet and probiotics, making it difficult to delineate the beneficial effect of an individual intervention. It is possible that a different criterion for the diagnosis of gestational diabetes may have yielded changed estimates of effect. [46] Women in the control group may have accessed these interventions resulting in Hawthorne effect for the following reasons: interventions were easily accessible, including over the counter nutritional supplement; and absence of blinding of the women or health care provider, in any of the included studies. None of the studies evaluated GDM as a primary outcome. Hence it is possible that the different arms could have been treated differently, such as additional screening for GDM, and close follow-up in the intervention group, thereby influencing the outcome. Studies were limited in their reporting on proportion of women who complied with the intervention, which could have a major influence on the effect size observed.

Clinical applicability

Since women with GDM are mostly seen in the secondary care, with frequent follow ups including ultrasound assessment of fetal growth, any effective intervention that prevents GDM is likely to be cost effective in the long run. Dietary interventions are complex, and require a change in the behaviour of mothers, to have a positive impact on the outcomes. Furthermore, they require reinforcement and feedback with food diaries, and regular visits with healthcare professionals such as dieticians, midwives and clinicians. The diet based intervention may have a role in primary prevention of GDM, especially in obese and overweight pregnant women.

With a projected increase in the National Health Service (NHS) spend from £8.8 billion to £13 billion per year in the next 25 years on Type 2 diabetes and its complications, [47] primary prevention of GDM has significant societal and economic benefits. Interventions based on diet and nutritional supplements show potential to prevent GDM, with the possibility of promoting the health of subsequent generations, by reducing the risks of obesity and adult onset diabetes in children born to mothers with GDM.

Research recommendations

The role of diet-based interventions in obese and overweight pregnant women, the population most likely to develop GDM, needs further evaluation. The beneficial effects of simple interventions such as probiotics and myo-inositol on GDM appear promising. There is a need to evaluate the effects of supplements by large multicentre randomised trials, involving wider group of individuals such as non-Caucasians and obese women. The optimal dose, frequency and type of inositol isomer need to be identified. Similarly the effects of different genera or strains of probiotics and their varied dose on GDM need to be identified. Given the considerable resources required to deliver the complex interventions based on diet, it is possible that nutritional supplements will also be cost effective. Furthermore, they are an attractive option as they are easily available as over the counter supplements.

Conclusion

Mixed approach interventions composed of diet and lifestyle modification do not appear to prevent GDM. Diet based interventions may be beneficial in obese and overweight pregnant women. Nutritional supplements such as probiotics and myo-inositol show benefit and need further evaluation in large randomised trials.

Supporting Information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank the EBM-CONNECT (Evidence-based medicine collaboration: network for systematic reviews and guideline development research and dissemination) Collaboration, in alphabetical order by country: L. Mignini, Centro Rosarino de Estudios Perinatales, Argentina; P. von Dadelszen, L. Magee and D. Sawchuck, University of British Columbia Canada; E. Gao, Shanghai Institute of Planned Parenthood Research, China; B.W. Mol and K. Oude Rengerink, Academic Medical Centre, the Netherlands; J. Zamora, Ramon y Cajal, Spain; C. Fox and J. Daniels, University of Birmingham, UK; K.S. Khan, S. Thangaratinam, and C. Meads, Barts and the London School of Medicine, Queen Mary University of London, UK.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

The authors received funding from the European Union made available to the EBM-CONNECT Collaboration through its Seventh Framework Programme, Marie Curie Actions, International Staff Exchange Scheme (proposal no. 101377; grant agreement no. 247613). None of the funding providers played a role in the planning and execution of this work, or in drafting of the article.

References

- 1. Ferrara A (2007) Increasing Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A public health perspective. Diabetes Care 30(Supplement 2):S141–S146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jovanovic L, P DJ (2001) Gestational diabetes mellitus. JAMA 286(20):2516–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH (2002) Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 25(10):1862–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buchanan TA, Xiang AH, Page KA (2012) Gestational diabetes mellitus: risks and management during and after pregnancy. Nat Rev Endocrinol 8(11):639–49. 10.1038/nrendo.2012.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coustan DR (2013) Can a dietary supplement prevent gestational diabetes mellitus? Diabetes Care 36(4):777–9. 10.2337/dc12-2505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gillies CL, Abrams KR, Lambert PC, Cooper NJ, Sutton AJ, et al. (2007) Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 334(7588):299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kalergis M, Leung Yinko SS, Nedelcu R (2013) Dairy products and prevention of type 2 diabetes: implications for research and practice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 4:90 10.3389/fendo.2013.00090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weickert MO, Pfeiffer AF (2008) Metabolic effects of dietary fiber consumption and prevention of diabetes. J Nutr 138(3):439–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oostdam N, van Poppel MN, Wouters MG, van MW (2011) Interventions for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 20(10):1551–63. 10.1089/jwh.2010.2703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tieu J, Crowther CA, Middleton P (2008) Dietary advice in pregnancy for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD006674 10.1002/14651858.CD006674.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thangaratinam S, Rogozinska E, Jolly K, Glinkowski S, Roseboom T, et al. (2012) Effects of interventions in pregnancy on maternal weight and obstetric outcomes: meta-analysis of randomised evidence. BMJ 344:e2088 10.1136/bmj.e2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Luoto R, Kinnunen TI, Aittasalo M, Kolu P, Raitanen J, et al. (2011) Primary prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus and large-for-gestational-age newborns by lifestyle counseling: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 8(5):e1001036 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan KS, ter Riet G, Glanville J, Sowden AJ, Kleijnen J (2001) Undertaking Systematic Reviews of Research on Effectiveness. CRD's Guidance for Carrying Out or Commissioning Reviews. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. Report No.: 4 (2nd edition).

- 14. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, et al. (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000100 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walker JD (2008) NICE guidance on diabetes in pregnancy: management of diabetes and its complications from preconception to the postnatal period. NICE clinical guideline 63. London, March 2008. Diabet Med 25(9):1025–7. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02532.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higgins JPT, Green Se. Cochrane Reviewers Handbook 5.1.0. Available: http://handbook.cochrane.org/. 2011 Mar. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA (2006) A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med 25(20):3443–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bogaerts A, Devlieger R, Nuyts E, Witters I, Gyselaers W, et al. (2013) Effects of lifestyle intervention in obese pregnant women on gestational weight gain and mental health: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes 37(6):814–21. 10.1038/ijo.2012.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. D'Anna R, Scilipoti A, Giordano D, Caruso C, Cannata ML, et al. (2013) Myo-inositol supplementation and onset of gestational diabetes mellitus in pregnant women with a family history of type 2 diabetes: A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Care 36(4):854–7. 10.2337/dc12-1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dodd JM, Turnbull D, McPhee AJ, Deussen AR, Grivell RM, et al. (2014) Antenatal lifestyle advice for women who are overweight or obese: LIMIT randomised trial. BMJ 348:doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guelinckx I, Devlieger R, Mullie P, Vansant G (2010) Effect of lifestyle intervention on dietary habits, physical activity, and gestational weight gain in obese pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 91(2):373–80. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harrison CL, Lombard CB, Gibson-Helm M, Deeks A, Teede HJ (2011) Limiting excess weight gain in high-risk pregnancies: A randomized controlled trial. Endocr Rev 32(3). 10.1210/er.2011-0001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hui A, Back L, Ludwig S, Gardiner P, Sevenhuysen G, et al. (2011) Lifestyle intervention on diet and exercise reduced excessive gestational weight gain in pregnant women under a randomised controlled trial. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 119(1):70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jeffries K, Shub A, Walker SP, Hiscock R, Permezel M (2009) Reducing excessive weight gain in pregnancy: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust 191(8):429–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Korpi-Hyovalti E, Schwab U, Laaksonen DE, Linjama H, Heinonen S, et al. (2012) Effect of intensive counselling on the quality of dietary fats in pregnant women at high risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Br J Nutr 108(5):910–7. 10.1017/S0007114511006118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luoto R, Laitinen K, Nermes M, Isolauri E, Luoto R, et al. (2010) Impact of maternal probiotic-supplemented dietary counselling on pregnancy outcome and prenatal and postnatal growth: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Nutr 103(12):1792–9. 10.1017/S0007114509993898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Petrella E, Malavolti M, Bertarini V, Pignatti L, Neri I, et al. (2013) Gestational weight gain in overweight and obese women enrolled in a healthy lifestyle and eating habits program. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med November 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Phelan S, Phipps MG, Abrams B, Darroch F, Schaffner A, et al. (2011) Randomized trial of a behavioral intervention to prevent excessive gestational weight gain: the Fit for Delivery Study. Am J Clin Nutr 93(4):772–9. 10.3945/ajcn.110.005306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Polley BA, Wing RR, Sims CJ (2002) Randomized controlled trial to prevent excessive weight gain in pregnant women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 26(11):1494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Poston L, Briley AL, Barr S, Bell R, Croker H, et al. (2013) Developing a complex intervention for diet and activity behaviour change in obese pregnant women (the UPBEAT trial); Assessment of behavioural change and process evaluation in a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Quinlivan J, Lam LT, Fisher J (2011) A randomised trial of a four-step multidisciplinary approach to the antenatal care of obese pregnant women. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 51(2):141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Renault KM, Norgaard K, Nilas L, Carlsen EM, Cortes D, et al. (2014) The Treatment of Obese Pregnant Women (TOP) study: a randomized controlled trial of the effect of physical activity intervention assessed by pedometer with or without dietary intervention in obese pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 210(2):134–9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thornton YS, Smarkola C, Kopacz SM, Ishoof SB (2009) Perinatal outcomes in nutritionally monitored obese pregnant women: a randomized clinical trial. J Natl Med Assoc 101(6):569–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vesco K, Leo M, Gillman M, King J, McEvoy C, et al. (2013) Impact of a weight management intervention on pregnancy outcomes among obese women: The Healthy Moms Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 208(1):S352. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vinter C, Jensen DM, Ovesen P, Beck-Nielsen H, Jorgensen JS (2011) The LiP (Lifestyle in Pregnancy) study: a randomized controlled trial of lifestyle intervention in 360 obese pregnant women. Diabetes Care 34(12):2502–7. 10.2337/dc11-1150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Walsh J, McGowan CA, Mahony R, Foley ME, McAuliffe FM (2012) Low glycaemic index diet in pregnancy to prevent macrosomia (ROLO study): randomised control trial. BMJ 345:e5605 10.1136/bmj.e5605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wolff S, Legarth J, Vangsgaard K, Toubro S, Astrup A (2008) A randomized trial of the effects of dietary counseling on gestational weight gain and glucose metabolism in obese pregnant women. Int J Obes (Lond) 32(3):495–501. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barrett HL, Callaway LK, Nitert MD (2012) Probiotics: a potential role in the prevention of gestational diabetes? Acta Diabetol 49 Suppl 1:S1–13. 10.1007/s00592-012-0444-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fraser RB, Ford FA, Lawrence GF (1988) Insulin sensitivity in third trimester pregnancy. A randomized study of dietary effects. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 95[3], 223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang C, Liu S, Solomon CG, Hu FB (2006) Dietary fiber intake, dietary glycemic load, and the risk for gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 29(10):2223–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Qiu C, Williams MA, Vadachkoria S, Frederick IO, Luthy DA (2004) Increased maternal plasma leptin in early pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 103(3):519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pirc LK, Owens JA, Crowther CA, Willson K, De Blasio MJ, et al. (2007) Mild gestational diabetes in pregnancy and the adipoinsular axis in babies born to mothers in the ACHOIS randomised controlled trial. BMC Pediatr 7:18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Han S, Middleton P, Crowther CA (2012) Exercise for pregnant women for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7:CD009021 10.1002/14651858.CD009021.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Genazzani AD, Lanzoni C, Ricchieri F, Jasonni VM (2008) Myo-inositol administration positively affects hyperinsulinemia and hormonal parameters in overweight patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol 24(3):139–44. 10.1080/09513590801893232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cogram P, Tesh S, Tesh J, Wade A, Allan G, et al. (2002) D-chiro-inositol is more effective than myo-inositol in preventing folate-resistant mouse neural tube defects. Hum Reprod 17(9):2451–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shang M, Lin L (2014) IADPSG criteria for diagnosing gestational diabetes mellitus and predicting adverse pregnancy outcomes. J Perinatol 34(2):100–4. 10.1038/jp.2013.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hex N, Bartlett C, Wright D, Taylor M, Varley D (2012) Estimating the current and future costs of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in the UK, including direct health costs and indirect societal and productivity costs. Diabet Med 29(7):855–62. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03698.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.