SUMMARY

Testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT), which comprise 98% of all testicular malignancies, are the most commonly occurring cancers among men between the ages of 15 and 44 years in the United States (U.S.). A prior report from our group found that while TGCT incidence among all U.S. men increased between 1973 and 2003, the rate of increase among black men was more pronounced starting in 1989–1993 than was the rate of increase among other men. In addition, TGCT incidence increased among Hispanic white men between 1992 and 2003. To determine whether these patterns have continued, in the current study we examined temporal trends in incidence through 2011. Between 1992 and 2011, 21,271 TGCTs (12,419 seminomas; 8,715 nonseminomas; 137 spermatocytic seminomas) were diagnosed among residents of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 13 registry areas. The incidence of TGCT was highest among non-Hispanic white men (6.97 per 100,000 man-years) followed by American Indian/Alaska Native (4.66), Hispanic white (4.11), Asian/Pacific Islander (1.95), and black (1.20) men. Non-Hispanic white men were more likely to present with smaller tumors (3.5 cm) and localized disease (72.6%) than were men of other races/ethnicities. Between 1992 and 2011, TGCT incidence increased significantly among Hispanic white (APC: 2.94, p<0.0001), black (APC: 1.67, p=0.03), non-Hispanic white (APC: 1.23, p<0.0001), and Asian/Pacific Islander (APC: 1.04, p=0.05) men. Incidence rates also increased, although not significantly, among American Indian/Alaska Native men (APC: 2.96, p=0.06). The increases were greater for nonseminoma than seminoma. In summary, while non-Hispanic white men in the U.S. continue to have the highest incidence of TGCT, they present at more favorable stages of disease and with smaller tumors than do other men. The increasing rates among non-white men, in conjunction with the larger proportion of non-localized stage disease, suggest an area where future research is warranted.

Keywords: testicular cancer, TGCT, trends, SEER, incidence, ethnic groups

INTRODUCTION

Testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT) are rare tumors in the general population but are the most commonly occurring cancer among men between the ages of 15 and 44 years in the United States (U.S.) (McGlynn & Cook 2009). Histologically, TGCTs are classified into three groups: seminomas, nonseminomas, and spermatocytic seminomas. Seminomas and nonseminomas account for the vast majority (98–99%) of TGCTs, while spermatocytic seminomas are very rare at all ages (Chia et al. 2010).

TGCT incidence rates have been increasing among white men in the U.S. over the last 40 years and recent data suggest that incidence rates are also changing among other racial/ethnic groups (Shah et al. 2007; Chien et al. 2014). A prior study by our group found that TGCT incidence rates increased in men of all racial/ethnic backgrounds between 1973 and 2003, however, different patterns in the increase were evident. Rates appeared to be stabilizing among non-Hispanic white, Asian/Pacific Islander (A/PI), and American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) men whereas rates increased among Hispanic white men between 1992 and 2003 (Shah et al. 2007). Since publication of that study, Hispanics (16.3%) surpassed blacks (12.6%) as the largest minority group in the U.S. (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). This shift in the U.S. population, along with the availability of more recent data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries, prompted further examination of TGCT trends by race/ethnicity. The current study sought to examine whether the patterns noted in our prior publication remained evident in more recent years and what new patterns have been emerging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The SEER program of the National Cancer Institute collects and publishes statistics from population-based cancer registries in the U.S. (Howlader et al. 2014). To examine time trends, data for the years 1992–2011 were drawn from the SEER 13 registries which cover approximately 14% of the population. The SEER 9 registries contain data back to 1973, but do not permit examination of rates by racial/ethnic groups other than white, black and all other men. Thus, for the current study, data from the SEER 13 registries were used as they report rates by racial/ethnic groups. The SEER 13 registries are located in San Francisco, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, Seattle, Utah, Atlanta, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Rural Georgia, and Alaska (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results 2013). Identification of Hispanic ethnicity was based on the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) Hispanic Identification Algorithm (NAACCR Race and Ethnicity Work Group). Identification of AI/AN race was restricted to men residing in the Contract Health Service Delivery Area (CHSDA) counties (Indian Health Service).

TGCT was defined using the International Classification of Disease for Oncology, 3rd ed. topography (C62) and morphology codes (seminoma: 9060–9062, 9064; nonseminoma: 9065–9102; spermatocytic seminoma: 9063) (Fritz 2000). In addition to age and race/ethnicity, data on histology, stage at diagnosis (localized, regional, distant), tumor size, and year of diagnosis were available for each TGCT case. Incidence rates per 100,000 man-years were calculated, age-adjusted to the U.S. 2000 standard population, as were rate ratios and their 95% confidence intervals. For the current study, TGCT incidence rates were calculated for non-Hispanic white, Hispanic white, A/PI, black, and AI/AN men. The majority (75.1%) of Hispanic persons reported their race as white; therefore it was not possible to calculate rates separately among Hispanics and non-Hispanics of the other races. Estimates of annual percent change (APC) were calculated for the 1992–2011 time period using the annual rates and weighted least squares regression (Kim et al. 2000). For temporal analysis, years of diagnosis were grouped into four periods: 1992–1996, 1997–2001, 2002–2006, and 2007–2011. Statistical significance was based on a two-sided p-value less than or equal to 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the SEER*Stat statistical package (version 8.1.5).

RESULTS

During the time period 1992–2011, 21,271 TGCTs (12,419 seminoma; 8,715 nonseminoma; 137 spermatocytic seminoma) were diagnosed among residents of the SEER 13 registry areas (Table 1). The rates of TGCT overall increased significantly during this time period (APC=1.11, p-value < 0.0001), with greater increases for nonseminoma (APC=1.55, p-value < 0.0001) than seminoma (APC: 0.80, p-value < 0.0003). The APC for spermatocytic seminoma could not be calculated due to small numbers, however incidence rates of spermatocytic seminoma remained constant throughout this time period.

Table 1.

Incidence of testicular germ cell tumors by histologic subtype, 1992–2011, SEER 13 Registries.

| All TGCT | Seminoma | Nonseminoma | Spermatocytic Seminoma | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Rate (95% CI)1 | Count | Rate (95% CI)1 | Count | Rate (95% CI)1 | Count | Rate (95% CI)1 | |

| 1992–2011 | 21,271 | 5.24 (5.17–5.31) | 12,419 | 3.10 (3.05–3.16) | 8,715 | 2.09 (2.05–2.14) | 137 | 0.04 (0.03–0.05) |

| All Races | ||||||||

| 1992–1996 | 4,726 | 4.75 (4.62–4.89) | 2,770 | 2.85 (2.74–2.96) | 1,926 | 1.87 (1.79–1.96) | 30 | 0.04 (0.03–0.06) |

| 1997–2001 | 5,190 | 5.12 (4.98–5.26) | 3,149 | 3.14 (3.03–3.25) | 2,013 | 1.95 (1.86–2.04) | 28 | 0.03 (0.02–0.05) |

| 2002–2006 | 5,463 | 5.35 (5.20–5.49) | 3,120 | 3.09 (2.98–3.20) | 2,297 | 2.20 (2.11–2.30) | 46 | 0.05 (0.04–0.07) |

| 2007–2011 | 5,892 | 5.67 (5.52–5.81) | 3,380 | 3.30 (3.19–3.41) | 2,479 | 2.33 (2.24–2.43) | 33 | 0.04 (0.03–0.05) |

| APC 2 | 1.11 3 | 0.80 3 | 1.55 3 | 4 | ||||

Rates are per 100,000 and age-adjusted to the 2000 US Standard Population (19 age groups - Census P25-1130)

APC = Annual Percent Change

The APC is significantly different from zero (p-value < 0.05)

APC could not be calculated

The incidence of TGCT was highest among non-Hispanic white men (6.97 per 100,000 man-years), followed by AI/AN (4.66), Hispanic white (4.11), and A/PI (1.95) men, while rates were lowest among black men (1.20) (Table 2). Rates for both seminomas and nonseminomas followed the same ranking, except the nonseminoma rate was higher among Hispanic white men than AI/AN men. Seminomas were more common than nonseminomas among all men, with the ratio of seminoma:nonseminoma ranging from 1.2 among Hispanic white men to 1.8 among black men. The Hispanic:non-Hispanic white rate ratio was 0.54 for the seminomas, significantly lower than the rate ratio of 0.66 for the nonseminomas. The rate ratios did not differ by type among the other racial/ethnic groups. The number of men with spermatocytic seminoma was too low to permit calculation of rates by racial/ethnic group.

Table 2.

Incidence of testicular germ cell tumors by race/ethnicity, 1992–2011, SEER 13 Registries.

| All TGCT | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | Tumor | Median | Tumor Stage (%) | ||||||

| Count | Rate1 | Ratio (95% CI) | Size (cm) | Age (Range) | Localized | Regional | Distant | Unknown | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 15,691 | 6.97 | 1.00 (referent) | 3.5 | 34 (0–103) | 72.6 | 17.2 | 9.4 | 0.8 |

| Hispanic White | 3,620 | 4.11 | 0.59 (0.57–0.61) | 4.5 | 29 (0–88) | 64.4 | 18.6 | 16.0 | 1.0 |

| A/PI 2 | 926 | 1.95 | 0.28 (0.26–0.30) | 4.5 | 33 (0–75) | 70.9 | 15.4 | 13.0 | 0.7 |

| Black | 514 | 1.20 | 0.17 (0.16–0.19) | 5.0 | 35 (0–70) | 61.1 | 21.8 | 15.3 | 1.8 |

| AI/AN 3 | 190 | 4.66 | 0.67 (0.58–0.78) | 5.3 | 28 (16–66) | 62.3 | 18.0 | 18.9 | 0.8 |

| Seminoma | Rate | Tumor | Median | Tumor Stage (%) | |||||

| Count | Rate1 | Ratio (95% CI) | Size (cm) | Age (Range) | Localized | Regional | Distant | Unknown | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 9,426 | 4.14 | 1.00 (referent) | 3.7 | 37 (14–87) | 80.4 | 13.8 | 5.0 | 0.8 |

| Hispanic White | 1,819 | 2.23 | 0.54 (0.51–0.57) | 4.7 | 32 (0–88) | 75.1 | 17.2 | 6.5 | 1.2 |

| A/PI 2 | 552 | 1.18 | 0.29 (0.26–0.31) | 4.9 | 31 (17–66) | 77.9 | 12.6 | 9.0 | 0.5 |

| Black | 319 | 0.77 | 0.19 (0.17–0.21) | 5.6 | 37 (13–70) | 65.4 | 22.9 | 9.6 | 2.1 |

| AI/AN 3 | 111 | 2.92 | 0.71 (0.58–0.86) | 5.0 | 33 (16–81) | 62.5 | 25.0 | 12.5 | 0.0 |

| Nonseminoma | Rate | Tumor | Median | Tumor Stage (%) | |||||

| Count | Rate1 | Ratio (95% CI) | Size (cm) | Age (Range) | Localized | Regional | Distant | Unknown | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 6,152 | 2.78 | 1.00 (referent) | 3.5 | 29 (0–103) | 60.6 | 22.4 | 16.2 | 0.8 |

| Hispanic White | 1,785 | 1.85 | 0.66 (0.63–0.70) | 4.3 | 25 (0–63) | 53.7 | 25.5 | 25.5 | 0.8 |

| A/PI 2 | 372 | 0.76 | 0.27 (0.24–0.30) | 4.1 | 26 (0–75) | 61.3 | 18.5 | 18.5 | 1.0 |

| Black | 190 | 0.42 | 0.15 (0.13–0.18) | 4.5 | 30 (0–66) | 54.1 | 24.7 | 24.7 | 1.4 |

| AI/AN 3 | 79 | 1.75 | 0.63 (0.49–0.79) | 5.7 | 25 (16–43) | 62.0 | 8.0 | 28.0 | 2.0 |

Rates are per 100,000 and age-adjusted to the 2000 US Standard Population (19 age groups – Census P25-1130)

A/PI = Asian/Pacific Islander

AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native

Median tumor size was smallest among non-Hispanic white men (3.5 cm) and largest among AI/AN men (5.3 cm) (Table 2). For seminoma and nonseminoma, the largest median tumor size was 5.6 cm among black men and 5.7 cm among AI/AN men, respectively. Median age at TGCT diagnosis was youngest among Hispanic white men (29 years) and oldest among black men (35 years). The median age at diagnosis of seminoma was 36 years among all men, while the median age at diagnosis of nonseminoma was 28 years (data not shown). The majority of tumors were diagnosed at localized stages in all men; however non-Hispanic white men had the highest percentage of localized disease (72.6%) while black men had the lowest (61.1%). Nonseminomas were more commonly diagnosed at non-localized stages (40.3%) than were seminomas (20.3%) (data not shown).

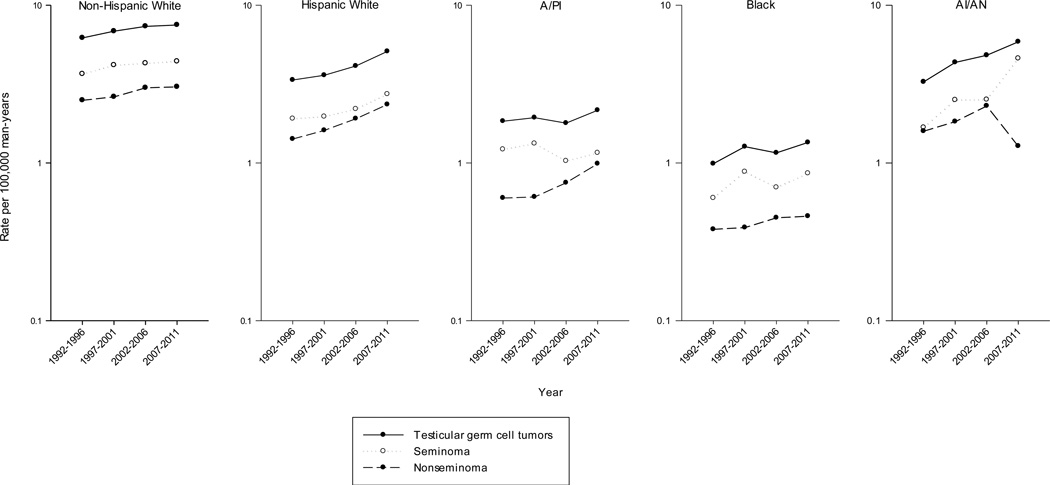

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 1, TGCT incidence rates increased significantly from 1992–1996 to 2007–2011 among four of the five racial/ethnic groups, most notably among Hispanic white men (APC: 2.94, p-value < 0.0001), followed by black (APC: 1.67, p-value=0.03), non-Hispanic white (APC: 1.23, p-value < 0.0001), and A/PI (APC: 1.04, p-value=0.05) men. Incidence rates also increased among AI/AN men (APC: 2.96, p-value=0.06), however this increase was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Incidence of testicular germ cell tumors by race/ethnicity and year of diagnosis, 1992–2011, SEER 13 Registries.

| Testicular germ cell tumors | Seminoma | Nonseminoma | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Rate (95% CI)1 | Count | Rate (95% CI)1 | Count | Rate (95% CI)1 | |

| Non-Hispanic White | ||||||

| 1992–1996 | 3,771 | 6.21 (6.01–6.41) | 2,243 | 3.67 (3.52–3.82) | 1,503 | 2.50 (2.37–2.63) |

| 1997–2001 | 3,965 | 6.85 (6.64–7.07) | 2,458 | 4.17 (4.01–4.34) | 1,482 | 2.63 (2.50–2.77) |

| 2002–2006 | 3,999 | 7.35 (7.12–7.58) | 2,370 | 4.29 (4.12–4.47) | 1,593 | 3.00 (2.85–3.15) |

| 2007–2011 | 3,956 | 7.50 (7.27–7.74) | 2,355 | 4.41 (4.24–4.60) | 1,574 | 3.04 (2.89–3.20) |

| APC 2 | 1.23 3 | 1.14 3 | 1.37 3 | |||

| Hispanic White | ||||||

| 1992–1996 | 600 | 3.36 (3.07–3.68) | 311 | 1.91 (1.68–2.17) | 286 | 1.42 (1.25–1.62) |

| 1997–2001 | 775 | 3.60 (3.34–3.89) | 396 | 1.97 (1.77–2.20) | 377 | 1.61 (1.45–1.80) |

| 2002–2006 | 982 | 4.17 (3.90–4.46) | 479 | 2.20 (2.00–2.42) | 495 | 1.91 (1.74–2.09) |

| 2007–2011 | 1,263 | 5.10 (4.81–5.40) | 633 | 2.73 (2.51–2.96) | 627 | 2.35 (2.17–2.55) |

| APC 2 | 2.94 3 | 2.43 3 | 3.54 3 | |||

| A/PI 4 | ||||||

| 1992–1996 | 183 | 1.84 (1.58–2.14) | 117 | 1.22 (1.00–1.47) | 65 | 0.60 (0.46–0.78) |

| 1997–2001 | 218 | 1.94 (1.69–2.22) | 146 | 1.33 (1.12–1.57) | 72 | 0.61 (0.47–0.77) |

| 2002–2006 | 225 | 1.79 (1.56–2.04) | 129 | 1.03 (0.86–1.23) | 96 | 0.75 (0.61–0.92) |

| 2007–2011 | 300 | 2.16 (1.93–2.43) | 160 | 1.16 (0.99–1.36) | 139 | 0.99 (0.84–1.18) |

| APC 2 | 1.04 3 | −0.72 | 3.69 3 | |||

| Black | ||||||

| 1992–1996 | 102 | 0.99 (0.80–1.22) | 60 | 0.60 (0.46–0.79) | 41 | 0.38 (0.27–0.53) |

| 1997–2001 | 134 | 1.27 (1.06–1.51) | 91 | 0.88 (0.71–1.09) | 43 | 0.39 (0.28–0.53) |

| 2002–2006 | 126 | 1.16 (0.97–1.39) | 73 | 0.70 (0.54–0.88) | 51 | 0.45 (0.33–0.59) |

| 2007–2011 | 152 | 1.35 (1.14–1.58) | 95 | 0.86 (0.70–1.06) | 55 | 0.46 (0.35–0.61) |

| APC 2 | 1.67 3 | 1.21 | 1.75 | |||

| AI/AN 5 | ||||||

| 1992–1996 | 30 | 3.27 (2.18–4.88) | 14 | 1.68 (0.90–3.03) | 16 | 1.59 (0.90–2.83) |

| 1997–2001 | 41 | 4.34 (3.10–6.02) | 23 | 2.51 (1.58–3.91) | 18 | 1.83 (1.08–3.04) |

| 2002–2006 | 54 | 4.82 (3.60–6.42) | 26 | 2.52 (1.64–3.81) | 28 | 2.30 (1.52–3.47) |

| 2007–2011 | 65 | 5.87 (4.51–7.58) | 48 | 4.60 (3.37–6.17) | 17 | 1.28 (0.73–2.16) |

| APC 2 | 2.96 | 6 | −0.18 | |||

Rates are per 100,000 and age-adjusted to the 2000 US Standard Population (19 age groups - Census P25-1130)

APC = Annual Percent Change

The APC is significantly different from zero (p-value < 0.05)

A/PI = Asian/Pacific Islander

AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native

APC could not be calculated

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted incidence rates of testicular germ cell tumors among non-Hispanic white, Hispanic white, Asian/Pacific Islander (A/PI), black, and American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) men, SEER-13 registries, 1992–1996 to 2007–2011

TGCT rates by histologic subtype are also presented in Table 3 and Figure 1. Seminoma rates increased significantly among both Hispanic (APC: 2.43, p-value < 0.0001) and non-Hispanic white (APC: 1.14, p-value= 0.0001) men, while rates among black men rose non-significantly (APC: 1.21, p-value= 0.18), and did not change greatly among A/PI men (APC: −0.72, p-value= 0.33). The APC for seminoma among AI/AN men could not be calculated due to small numbers. Nonseminoma rates increased significantly among A/PI (APC: 3.69, p-value < 0.0001), Hispanic white (APC: 3.54, p-value < 0.0001) and non-Hispanic white (APC: 1.37, p-value= 0.0001) men, and non-significantly among black men (APC: 1.75, p-value=0.14). In comparison, nonseminoma rates did not change consistently among AI/AN men (APC: −0.18, p-value= 0.93). Among each racial/ethnic group where the APCs for both types could be estimated, the increases were greater for nonseminoma than seminoma.

DISCUSSION

During the years 1992–2011, non-Hispanic white men remained the racial/ethnic group with the highest incidence of TGCT in the U.S.; rates were intermediate among Hispanic white and AI/AN men, and were lowest among black and A/PI men. Over the 20-year period evaluated, the TGCT incidence rate continued to increase among men of all racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. Similar to the findings of our previous study (Shah et al. 2007), the current study found that the most pronounced increase in TGCT rates was among Hispanic white men. In contrast to our previous study where TGCT rates of A/PI and AI/AN men could not be distinguished, we found that TGCT increased significantly among A/PI men and non-significantly among AI/AN men.

It remains unclear why there are differences in TGCT risk among different racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. The only well-described risk factors for TGCT are personal history of TGCT, family history of TGCT, cryptorchidism, hypospadias, and impaired spermatogenesis (McGlynn & Cook 2009). This constellation of male reproductive disorders, termed the Testicular Dysgenesis Syndrome (TDS), has been suggested to share a common in utero etiology (Skakkebaek 2003). Whether the prevalence of all TDS conditions varies by racial/ethnic group is not certain. An examination of the prevalence of cryptorchidism in the Collaborative Perinatal Project, however, found that white babies had higher rates than black babies, but the difference in prevalence was far lower than the difference in TGCT incidence (McGlynn et al. 2006).

The notable disparity in TGCT risk by racial/ethnic group and the increased risk among first degree relatives has supported the existence of a strong genetic component to TGCT susceptibility. Although linkage studies have failed to identify a major gene effect (Crockford et al. 2006; Kratz et al. 2010), genome wide association studies (GWAS) have thus far identified 16 loci associated with TGCT susceptibility (Kanetsky et al. 2009; Rapley et al. 2009; Turnbull et al. 2010; Chung et al. 2013; Ruark et al. 2013; Schumacher et al. 2013). While genetic susceptibility to TGCT may explain some of the difference in rates observed by race/ethnicity, it cannot explain, by itself, the steady increases in rates seen since the mid-twentieth century. These rapid increases in incidence suggest that environmental factors play an important role in etiology (Adami et al. 1994). Factors that have been hypothesized to be involved include exposures such as maternal nutrition and maternal exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals, among others (McGlynn & Cook 2009). Assessing in utero exposures, however, is challenging due to the time lag between exposure of the mother and TGCT occurrence in the son. Nevertheless, meta-analyses have found that TGCT is significantly associated with cryptorchidism, inguinal hernia, twinning, birth weight, gestational age, maternal bleeding, birth order, sibship size, and possibly caesarean section (Cook et al. 2009; Cook et al. 2010).

The largest increase in TGCT incidence seen in the current study occurred among Hispanic white men. Although the ancestry of the U.S. Hispanic population can be traced back to numerous countries, the majority of Hispanics in the U.S., based on the 2010 census, were of Mexican descent (63%), followed by Puerto Rican (9%), and Cuban (4%) (Ennis et al. 2011). Estimated TGCT incidence rates in Mexico (2.8 per 100,000, age-adjusted using the world standard population), Puerto Rico (3.1), and Cuba (1.4) (Ferlay et al. 2013) are variable, but all are lower than the rate among U.S. Hispanics of all races (3.9). It is possible that the reported rates are lower in Mexico, Puerto Rico and Cuba than among Hispanic whites in the U.S. because the overall rates in non-U.S. countries include men of all races. Alternatively, it is possible that rates among Hispanic whites rise with migration to the U.S. Previous migrant studies have shown that changes in TGCT incidence do not occur among the first generation of migrants, but rather, among the second generation (Parkin & Iscovich 1997; Hemminki & Li 2002). Thus, it is possible that the increase in TGCT rates among the U.S. Hispanic white population could be related to birthplace of the men, however, information on migration status is not available in SEER registries.

In the current study, the racial/ethnic group with the highest incidence of TGCT (non-Hispanic white men) also had the highest proportion of tumors diagnosed at localized stage (72.6%). It is not clear why the proportion of tumors diagnosed at local stages would vary by racial/ethnic group. There is no screening program in the U.S., so TGCT is most frequently detected when men become symptomatic. Thus, socio-demographic factors, particularly health insurance coverage and access to health care (Lerro et al. 2014), may be a factor.

A strength of the current study was the use of SEER registry data, which is population-based and captured a large sample of the U.S. population including data on race/ethnicity and incidence data over 20 years. Limitations included the inability to examine Hispanic ethnicity among races other than whites due to small numbers and the lack of information on place of birth, which may be useful in distinguishing between environmental and genetic risk factors of TGCT.

In summary, the current study suggests that TGCT incidence is increasing among men of all racial/ethnic backgrounds in the U.S., with the most pronounced increase in Hispanic white men. The increasing rates among non-white men, along with the larger proportion of non-localized stage disease, suggest an area where both etiologic research and public health efforts could be targeted.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by the intramural research program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AAG acquired the data, designed the study, analyzed/interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. BT designed the study, drafted the manuscript, and helped with data analysis/interpretation. SSD helped with study design and data analysis/interpretation. KAM oversaw the study, helped with study design and data interpretation. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Adami HO, Bergstrom R, Mohner M, Zatonski W, Storm H, Ekbom A, Tretli S, Teppo L, Ziegler H, Rahu M, et al. Testicular cancer in nine northern European countries. Int J Cancer. 1994;59:33–38. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910590108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia VM, Quraishi SM, Devesa SS, Purdue MP, Cook MB, McGlynn KA. International trends in the incidence of testicular cancer, 1973–2002. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1151–1159. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien FL, Schwartz SM, Johnson RH. Increase in testicular germ cell tumor incidence among Hispanic adolescents and young adults in the United States. Cancer. 2014;120:2728–2734. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CC, Kanetsky PA, Wang Z, Hildebrandt MA, Koster R, Skotheim RI, et al. Meta-analysis identifies four new loci associated with testicular germ cell tumor. Nat Genet. 2013;45:680–685. doi: 10.1038/ng.2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook MB, Akre O, Forman D, Madigan MP, Richiardi L, McGlynn KA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of perinatal variables in relation to the risk of testicular cancer--experiences of the mother. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1532–1542. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook MB, Akre O, Forman D, Madigan MP, Richiardi L, McGlynn KA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of perinatal variables in relation to the risk of testicular cancer--experiences of the son. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1605–1618. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockford GP, Linger R, Hockley S, Dudakia D, Johnson L, Huddart R, et al. Genome-wide linkage screen for testicular germ cell tumour susceptibility loci. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:443–451. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Rios-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic Population: 2010: 2010 Census Briefs. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet] Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. [[accessed 20 June 2014]]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr, [Google Scholar]

- Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A, Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin LH, Parkin MD, editors. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) 3rd edn. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hemminki K, Li X. Cancer risks in Nordic immigrants and their offspring in Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:2428–2434. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KAe. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2011. National Cancer Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Indian Health Service: Contract Health Services Delivery Areas (CHSDA) [[accessed on 22 April 2014]]; https://www.ihs.gov/chs/index.cfm?module=chs_requirements_chsda.

- Kanetsky PA, Mitra N, Vardhanabhuti S, Li M, Vaughn DJ, Letrero R, Ciosek SL, Doody DR, Smith LM, Weaver J, Albano A, Chen C, Starr JR, Rader DJ, Godwin AK, Reilly MP, Hakonarson H, Schwartz SM, Nathanson KL. Common variation in KITLG and at 5q31.3 predisposes to testicular germ cell cancer. Nat Genet. 2009;41:811–815. doi: 10.1038/ng.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19:335–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratz CP, Mai PL, Greene MH. Familial testicular germ cell tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24:503–513. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerro CC, Robbins AS, Fedewa SA, Ward EM. Disparities in stage at diagnosis among adults with testicular germ cell tumors in the National Cancer Data Base. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:23. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.08.012. e15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn KA, Cook MB. Etiologic factors in testicular germ-cell tumors. Future Oncol. 2009;5:1389–1402. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn KA, Graubard BI, Klebanoff MA, Longnecker MP. Risk factors for cryptorchism among populations at differing risks of testicular cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:787–795. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAACCR Race and Ethnicity Work Group. NAACCR Guideline for Enhancing Hispanic/Latino Identification: Revised NAACCR Hispanic/Latino Identification Algorithm [NHIA v2.2.1] Springfield (IL): North American Association of Central Cancer Registries; 2011. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM, Iscovich J. Risk of cancer in migrants and their descendants in Israel: II. Carcinomas and germ-cell tumours. Int J Cancer. 1997;70:654–660. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970317)70:6<654::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapley EA, Turnbull C, Al Olama AA, Dermitzakis ET, Linger R, Huddart RA, Renwick A, Hughes D, Hines S, Seal S, Morrison J, Nsengimana J, Deloukas P, Rahman N, Bishop DT, Easton DF, Stratton MR. A genome-wide association study of testicular germ cell tumor. Nat Genet. 2009;41:807–810. doi: 10.1038/ng.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruark E, Seal S, McDonald H, Zhang F, Elliot A, Lau K, et al. Identification of nine new susceptibility loci for testicular cancer, including variants near DAZL and PRDM14. Nat Genet. 2013;45:686–689. doi: 10.1038/ng.2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher FR, Wang Z, Skotheim RI, Koster R, Chung CC, Hildebrandt MA, et al. Testicular germ cell tumor susceptibility associated with the UCK2 locus on chromosome 1q23. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:2748–2753. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MN, Devesa SS, Zhu K, McGlynn KA. Trends in testicular germ cell tumours by ethnic group in the United States. Int J Androl. 2007;30:206–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00795.x. discussion 213–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skakkebaek NE. Testicular dysgenesis syndrome. Horm Res. 2003;60(Suppl 3):49. doi: 10.1159/000074499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program: Overview of the SEER Program. [[accessed on 22 April 2014]]; http://seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 13 Regs Research Data, Nov 2012 Sub. [[accessed on 03 April 2014]];<Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969–2011 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch, released April 2013, based on the November 2012 submission. 1992–2010 http://www.seer.cancer.gov.

- Turnbull C, Rapley EA, Seal S, Pernet D, Renwick A, Hughes D, Ricketts M, Linger R, Nsengimana J, Deloukas P, Huddart RA, Bishop DT, Easton DF, Stratton MR, Rahman N. Variants near DMRT1, TERT and ATF7IP are associated with testicular germ cell cancer. Nat Genet. 2010;42:604–607. doi: 10.1038/ng.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]