Abstract

This study examined the longitudinal association between mood episode severity and relationships in BP youth. Participants were 413 Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth study youth, aged 12.6 ± 3.3 years. Monthly ratings of relationships (parents, siblings, and friends) and mood episode severity were assessed by the Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (ALIFE) Psychosocial Functioning Schedule (PFS) and Psychiatric Rating Scales (PSR) on average every 8.2 months over 5.1 years. Correlations examined whether participants with increased episode severity also reported poorer relationships, and also examined whether fluctuations in episode severity predicted fluctuations in relationships, and vice versa. Results indicated that participants with greater mood episode severity also had worse relationships. Longitudinally, participants had largely stable relationships. To the extent that there were associations, changes in parental relationships may precede changes in episode severity, although the magnitude of this finding was small. Findings have implications for relationship interventions in BP youth.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, interpersonal relationship functioning, longitudinal

Introduction

Family and peer relationships are crucial to youth, promoting healthy cognitive and emotional development (Hartup, 1996, Newcomb, 1995, Paradis et al., 2011, Youngblade et al., 2007) and helping to foster a sense of identity (Furman and Buhrmester, 1985). Psychopathology is associated with relationship impairment in youth, yet this research has only recently been extended to children and adolescents with bipolar (BP) disorder (referred to hereafter as BP youth) (Geller et al., 2000, Geller et al., 2002, Geller et al., 2004, Kim et al., 2007). The current study uses data from the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study (Axelson et al., 2006, Birmaher et al., 2006), a multi-site, prospective, naturalistic, longitudinal study, to examine the association between interpersonal functioning and mood episode severity in a large sample of BP youth. The study examines the bi-directional relationship between mood episode severity and relationships with friends and family longitudinally.

Developmental Significance of Family and Peer Relationships

Research with community samples of youth highlights the important role that family and peer relationships play in promoting healthy development. Positive family characteristics including engagement, closeness, and communication are associated with many positive outcomes in youth such as social competence, health-promoting behavior, self-esteem, and fewer internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Youngblade et al., 2007). Feeling highly valued and having a confidante in the family (either a parent or sibling) during adolescence is associated with many positive outcomes in adulthood including higher self-esteem, greater satisfaction with social support, fewer interpersonal problems, greater career satisfaction, higher SES, and lower tobacco use (Paradis et al., 2011).

Healthy peer relationships also provide numerous developmental benefits. Positive experiences with close friends during adolescence predict healthy adult relationships (Connolly and Goldberg 1999). Additionally, positive peer experiences protect youth from multiple social and psychological difficulties (Erath et al. 2010) including depressive symptoms (Hussong 2000; La Greca and Harrison 2005). Thus, family and peer relationships promote healthy development and protect youth from negative outcomes.

Mood symptoms in BP youth

Mood symptomatology in BP youth is typically episodic with syndromal and subsyndromal episodes characterized by primarily depressive and mixed symptoms and rapid mood changes (Birmaher et al., 2009a). In a study by Birmaher and colleagues (2009b), BP children in a depressive episode experienced more severe irritability, while BP adolescents in a depressive episode experienced more severe depressive symptoms, higher rates of melancholic and atypical symptoms, and suicide attempts. Adjusting for sex, socioeconomic status, and duration of illness, while manic, BP adolescents showed more ‘typical’ and severe manic symptoms. Axelson and colleagues (Axelson et al., 2011) found that children and adolescents who meet criteria for BP-NOS, particularly those with a family history of BP, frequently progress to BP-I or BP-II, and can subsequently experience more frequent and longer manic, hypomanic, depressive, or mixed episodes.

Given the unique symptom presentation of BP youth, there are many reasons to hypothesize that mood symptoms and family and peer relationships might affect one another. The severe irritability commonly seen in BP children's depressive episodes (Birmaher, 2009b) might lead to greater conflict both within the family and with peers. Additionally, atypical depression, as often seen in BP adolescents, is characterized by an extreme sensitivity to interpersonal rejection (Parker, 2002). This rejection sensitivity could be expected to lead to more conflict in familial relationships in addition to difficulty initiating and maintaining peer relationships. Conflict or rejection by family and peers might also be expected to worsen symptoms of depression, particularly among youth with rejection sensitivity (Chango et al., 2012). Some manic symptoms such as grandiosity, irritability, pressured speech, and risk-taking behavior (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) might also be expected to interfere with both familial and peer relationships.

The episodic nature of BP in itself, rendering BP youth to be somewhat unpredictable in day-to-day functioning, would be expected to create a great deal of stress and conflict in the home and to render peer relationships difficult to maintain over time. Similarly, peer and sibling relationships are important in particular for BP youth, as they may serve as a source of support (Pellegrini et al., 1986). Thus, less stable relationships might lead to decreased support and greater mood instability.

Family and peer relationship functioning in BP youth

Research has examined some elements of family and peer functioning in BP youth and, overall, found significant impairment. Regarding familial relationships, Belardinelli and colleagues (2008) found that parents of BP youth reported lower levels of family cohesion and expressiveness, and higher levels of conflict compared to parents with healthy children. Schnekel and colleagues (2008) reported that, compared to controls, parent-child relationships in families with BP youth were characterized by significantly less warmth, affection, and intimacy, and more quarreling and forceful punishment.

BP youth also have impaired peer relationships (Geller et al., 2000; Goldstein et al., 2009). Geller and colleagues (2000) found that BP youth reported having “few or no friends” more frequently and had more impaired social skills than both community control youth and youth with ADHD. Goldstein and colleagues (2009) combined relationships with family and friends into one “interpersonal relationships” construct, and found these relationships to be mildly to moderately impaired in BP youth.

Association between mood symptoms and relationship functioning in BP

While the majority of research examining family and peer relationships in BP youth has focused on characterizing these relationships, some studies have explored the association between family and peer functioning and mood symptomatology. In studies of BP adolescents and adults, interpersonal difficulties have been associated with greater symptom severity and higher rates of relapse, when measured at the same time point (i.e., cross-sectionally) (Johnson et al., 2003, Sullivan and Miklowitz, 2010, Uebelacker et al., 2006, Wingo et al., 2010). Cross-sectional studies, however, do not elucidate the associations between mood and interpersonal functioning over time. Longitudinal studies, in which mood and interpersonal functioning are both assessed over time at multiple time points, can further examine this association.

Some longitudinal studies have been conducted on adults with BP, revealing that interpersonal variables predict subsequent depression over time (Johnson et al., 2000, Johnson et al., 1999, Weinstock and Miller, 2008, Yan et al., 2004). However, one study (Uebelacker et al., 2006) did not find this association. The reverse association, that mood predicts psychosocial outcomes, has also been found (Goldberg and Harrow, 2005). In BP youth, low maternal warmth and stress in family and romantic relationships are associated with faster relapse and longer time to symptom improvement (Geller et al., 2002, Geller et al., 2004, Kim et al., 2007). In BP adolescents, changes in family conflict and cohesion predict changes in mood symptoms over time (Sullivan et al., 2012). No longitudinal studies have examined the effect of mood symptomatology on interpersonal functioning in BP youth or examined the reciprocal nature of these associations.

Current study

The current study uses data from the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study (Axelson et al., 2006, Birmaher et al., 2006), a multi-site, prospective, naturalistic, and longitudinal study. Intake data from the COBY study revealed mild to moderate levels of impairment in interpersonal and work functioning overall (Goldstein et al., 2009). In addition, mania, but not depression, was associated with impairment in interpersonal functioning (Esposito-Smythers et al., 2006). The current study extends these findings, and is the first to our knowledge that examines the bidirectional association between interpersonal functioning and mood episode severity longitudinally (over 5.1 years of prospective follow-up in this large sample of BP youth).

We examined whether those experiencing a more severe course of illness would experience poorer functioning with parents, siblings, and friends (comparisons among different groups of participants, or between-person analyses). We expected that a more severe course of illness would indicate poorer interpersonal relationship functioning, as has been found in previous research (Johnson et al., 2003, Sullivan and Miklowitz, 2010, Uebelacker et al., 2006, Wingo et al., 2010). Next, we examined whether changes in mood episode severity (depression and mania) predicted changes in interpersonal functioning, or vice versa, over time (comparisons of the same participant at different time points, or within-person analyses). These within-person analyses examined participants continuously across the entire follow-up period and around the onset of a mood episode. We expected a bi-directional relationship between the two variables of interest, indicating that greater mood episode severity would predict poorer family and peer relationships and relationships would predict subsequent mood episode severity over time. This prediction was based on previous research, which has found mood episode severity to predict poorer psychosocial functioning and interpersonal variables to predict mood episode severity over time, although bi-directional relationships have not been examined in the same study (Esposito-Smythers et al., 2006, Goldstein et al., 2009).

Analyses examined mood episodes dimensionally, taking into account subsyndromal symptoms including cases in which there were residual symptoms between episodes, which is consistent with previous literature (Johnson et al., 2000, Johnson et al., 1999, Weinstock and Miller, 2008, Goldberg and Harrow, 2005), as well as more discrete classic periods as defined by DSM-IV in which a new onset would be determined after a period of remission.

Method

Data are from the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study, which has been described previously (Axelson et al., 2006, Birmaher et al., 2006). All procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of each participating study location (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Brown University, and University of California Los Angeles). At intake, participants met the following criteria: (1) age 7-17 years; (2) DSM-IV bipolar I (BP-I), bipolar II (BP-II), or study-operationalized bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (BP-NOS) (Axelson et al., 2006); (3) intellectual functioning within normal limits. Participants with schizophrenia, intellectual disabilities, autism, or mood disorders secondary to substances, medications, or medical illness were excluded.

Procedure

After informed consent and assent were obtained, COBY diagnosticians interviewed children directly, and parents about their children. For younger participants (<12; 44.8%), the child and parent were interviewed together. Participants were enrolled on a rolling basis from 2000 to 2006 and were followed for an average of 5.1 ± 1.8 years. Interviews were conducted every 8.2 months on average.

Measures

Mood episode severity

Longitudinal changes in mood episode severity since the previous evaluation were tracked on a weekly basis via a procedure similar to the timeline follow-back (TLFB) method (Sobell, 2008), using the A-LIFE's Psychiatric Status Rating Scales (PSR) (Warshaw, 2001). The PSR scales were developed to generate analyzable data about the course of a participant's psychopathology (Keller et al., 1987). The PSR uses numeric values that have been operationally linked to the DSM-IV criteria, which is gathered in the interview and then translated into ratings. Scores on the PSR scales range from 1 (no symptoms) to 2–4 (subthreshold symptoms and impairment) to 5–6 (full criteria with different degrees of severity or impairment) (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Psychiatric Status Ratings (PSR)

| Code | Term | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | Definite Criteria (Severe) | Meets DSM-IV criteria for definite episode and has either prominent psychotic symptoms or extreme impairment in functioning. |

| 5 | Definite Criteria | Meets DSM-IV criteria for definite, current episode, but has no prominent psychotic symptoms or extreme impairment in functioning. |

| 4 | Marked | Does not meet full DSM-IV criteria but has major symptoms or impairment from the disorder. |

| 3 | Partial Remission | Considerably less psychopathology than full criteria with no more than moderate impairment in functioning, but still has obvious evidence of the disorder. This category may represent a worsening or an improvement in the participant's prior status (e.g., a depressive episode with only 2/3 symptoms in a moderate degree, or 1/2 symptoms in a severe degree). |

| 2 | Residual | Either participant claims to not be completely back to “usual self,” or rater notes the presence of one or more symptoms of the disorder in no more than a mild degree (e.g., depressive episode with mild insomnia as only residual symptom). |

| 1 | Baseline | Participant returns to “usual self” without any residual symptoms of the disorder, but may or may not have significant symptoms from some other condition or disorder (if so, this should be coded under that condition or disorder). |

Note: The Psychiatric Status Rating (PSR) was developed to generate analyzable data about the course of a participant's psychopathology. The PSR's are numeric values that have been operationally linked to the DSM-IV criteria. The interviewer reviews the participant's symptoms reported at the last interview, and then probes for changes in symptomotology forward in time to the current interview date. These “change points” are later translated by the interviewer into PSR ratings (indicating the severity level of an episode, as well as whether the participant has recovered or relapsed) for each week of the follow-up period. Although the PSR ratings are made on a week-by-week basis, the participant is not asked about how s/he was feeling during each week; instead, the interviewer utilizes the “change points” reported by the participant, and assigns a corresponding weekly PSR rating based upon these “change points.”

To obtain data for the PSR ratings, the interviewer reviews the participant's symptoms reported at the last interview, and then probes for changes in symptomatology forward in time to the current interview date. These “change points” are later translated by the interviewer into PSR ratings (indicating the severity level of an episode, as well as whether the participant has recovered or relapsed) for each week of the follow-up period. Thus, the interviewer rates each week at the same PSR number until there is a “change point” identified, then rates all subsequent weeks at this PSR number until there is another “change point” identified.

For analyses, mania and hypomania scores were integrated to one scale (1-8), where 5 and 6 indicated syndromal hypomania and 7 and 8 indicated syndromal mania. This allowed for severity of mania/hypomania to be examined together in order to reflect the dimensional nature of our analyses. 1 This analytic strategy has been utilized in a prior COBY publication (Hower et al., 2013), and is based upon a procedure in which the interviewer assesses all mania symptoms with one set of questions, which are then coded on the PSR as interdependent lines for mania and hypomania. Thus, depression severity was rated on a scale of 1-6 while (hypo)mania severity was rated on a scale of 1-8. Consensus scores obtained after interviewing parents and children were used, and were used for all study analyses. A monthly score was then obtained by using the worst weekly rating per month.

Interpersonal relations

The Psychosocial Functioning Schedule (PFS) of the Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (A-LIFE) (Keller et al., 1987) examines functioning in four domains. The present study used the interpersonal relations domain, which examines relations with parents, friends, and siblings separately. Ratings reflect relationship quality (the degree to which they feel close, the frequency of their arguments and the level to which they are resolved, the presence of active or passive avoidance, and the level of contentment or desire to improve the relationship) in these three relationship categories during the worst week of the preceding month. Having already discussed their mood symptoms since the previous interview, participants are asked to report on their relationship functioning by focusing on the week with the most impairment (i.e., from symptom presentation and/or problems within their relationships) within each month. Thus, the interviewer asks the participant to select the one week of each month with the most impairment, utilizing relevant “change points” that were identified in the PSR as anchors. The worst week of the month, rather than the average over the course of the month, was chosen because (1) average ratings would likely reduce week-to-week variability and (2) measurement of psychosocial functioning would be more in line with measurement of mood episode severity.

The measure was developed by Keller et al. (1987) and has been utilized in many subsequent studies (e.g., DelBello et al., 2007; Goldstein et al., 2009; Leon et al., 1999; Leon et al., 2000; Miklowitz et al., 2007; Philips et al., 2006). Ratings of 1-5 indicate that all relationships in the given category (i.e., parents, siblings, friends) would be rated at the same level of functioning, with 1 indicating relationships in the given category were “very good”, 2 “good,” 3 “fair/slightly impaired,” 4 “poor/moderately impaired,” and 5 “very poor/severely impaired.” Additional ratings were given if relationships within the parents or siblings categories varied in quality during the worst week of the preceding month. A 6 indicates that, although variable, at least one relationship in the category was good or better, while a 7 indicates that none of the relationships in the category were good or better (See Tables 2 and 3). For the purpose of analysis in the present study, 6 was recoded as a 2 (e.g., “good,” because at least one relationship in the category was rated as good) and 7 as a 4 (e.g., “poor”, because no relationship in the category was rated as good2). Consensus scores obtained after interviewing parents and children were used for all study analyses. The PFS has sound psychometric properties among individuals with affective disorders (Leon et al., 2000, Leon et al., 1999), and has been widely used in studies examining functional outcome in BP (Miklowitz et al., 2007) and other adolescent clinical populations (Phillips et al., 2006).

Table 2.

Interpersonal relationships with parents and siblings over 5-year follow-up

| Rating Category | Rating Description |

|---|---|

| 1-Very good | Close- experiences very close emotional relationships with this (these) family members, with only transient friction which is rapidly resolved. Feels only minor or occasional need to improve quality of relationship, which is usually close and satisfying. |

| 2-Good | Argues occasionally, but arguments are usually resolved satisfactorily within a short time. May occasionally prefer not to be with them because of dissatisfaction with them or be actively working with them to improve relationship. |

| 3-Fair | Often argues with this (these) family member(s) and takes a long time to resolve arguments. May withdraw from this (these) person(s) due to dissatisfaction. Often thinks that relationship needs to be either more harmonious or closer emotionally even when no conflict is present. For those relatives not living with the participant, contacts with them are less frequent by choice than feasible or rarely enjoyed very much when made. |

| 4-Poor | Regularly argues with this (these) family member(s) and such arguments are rarely ever resolved satisfactorily. Regularly prefers to avoid contact with them and/or feels great deficit in emotional closeness. For those family members out of the household, participant avoids seeing as much as possible and derives little pleasure from contact when made. |

| 5-Very poor | Either constantly argues with this (these) family member(s) or withdraws from them most of the time. |

| 6-Variable-good | Different levels for various members of this group, and would not warrant a rating of good or better (2, 1) with at least one member of this group. |

| 7-Variable-poor | Different levels for various members of this group, and would not warrant a rating of good or better (2, 1) with any member of this group. |

Note: Participants are asked about their relationships with their parents and siblings since the last interview. Specifically, participants report with respect to each relationship (a) the degree to which they feel close, (b) the frequency of their arguments and the level to which they are resolved, (c) the presence of active or passive avoidance, and (d) the level of contentment or desire to improve the relationship.

Having already discussed their mood symptoms, participants are asked to report on their relationship functioning with special focus on the week with the most impairment (i.e., from symptom presentation and/or problems within their relationships) within each month. The appropriate rating category for each “worst week” (as noted in the table above) is then determined by the interviewer and applied with respect to each month. Therefore, as opposed to averaging a weekly functioning score for each month, the relationship functioning score reflects the “worst week” (or most impaired week) for each month throughout the interval.

Table 3.

Interpersonal relationships with friends over 5-year follow-up

| Rating Category | Rating Description |

|---|---|

| 1-Very good | Had several special friends that he/she saw regularly and frequently and felt close to. |

| 2-Good | Had at least two special friends that he/she saw from time to time and was fairly close to. |

| 3-Fair | Had only one special friend that he/she saw from time to time and felt fairly close to, or contacts limited to several friends that he/she is not close to. |

| 4-Poor | Had no special friends that he/she saw from time to time and felt fairly close to, or contacts limited to one or two friends that he/she is not close to.) |

| 5-Very poor | Had no special friends and practically no social contacts. |

Note: Participants are asked about their relationships with their friends since the last interview. Specifically, participants report with respect to each relationship (a) the degree to which they feel close, (b) the frequency of their arguments and the level to which they are resolved, (c) the presence of active or passive avoidance, and (d) the level of contentment or desire to improve the relationship.

Having already discussed their mood symptoms, participants are asked to report on their relationship functioning with special focus on the week with the most impairment (i.e., from symptom presentation and/or problems within their relationships) within each month. The appropriate rating category for each “worst week” (as noted in the table above) is then determined by the interviewer and applied with respect to each month. Therefore, as opposed to averaging a weekly functioning score for each month, the relationship functioning score reflects the “worst week” (or most impaired week) for each month throughout the interval.

Analytic strategy

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2. We examined depression and mania separately, rather than conducting analyses for mixed episodes because participants experienced mixed episodes less than 1% of the follow-up time, providing insufficient power to analyze mixed episodes.

Interpersonal relations and psychiatric symptoms across five years

First, we calculated descriptive statistics for all variables and obtained between-person correlations by averaging each variable across the 5.1 years of data per person. We then examined the reciprocal relationships between interpersonal functioning and mood episode severity by calculating the lagged correlations (i.e., the relationship between two variables as observed at different time points) for each person, and using paired t-tests to determine whether 1-month lagged relationships differed in strength depending on the direction of the lag (i.e., interpersonal functioning predicting subsequent mood episode severity, vs. mood episode severity predicting subsequent interpersonal functioning).

Interpersonal relations and mood episode severity around onset of syndromal depression/mania

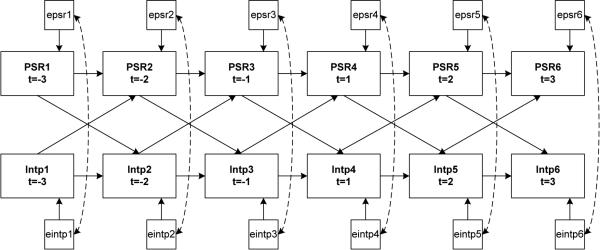

Finally, we focused analyses on the period of time around the onset of a mood episode (see Figure 1). For each participant, the first onset of syndromal depression or mania/hypomania (beyond the 3 month follow-up) was identified, and a cross-lagged model, which examines the direction of causality between two variables and estimates the strength of the causal effects of each variable on the other (Jackson et al., 2000), was fit to describe the relationship between interpersonal functioning and mood episode severity during the 3 months leading up to and the 3 months following the onset. Model fit was evaluated using chi-square values, where lack of statistical significance indicates good fit; the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (Bentler, 1990), where values ≥ 0.95 indicate good fit; and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (Browne, 1993), where values ≤ 0.06 indicate good fit. Both cutoff values are based on a simulation study (Hu, 1999).

Figure 1.

Cross-lagged path model of PSR psychiatric symptom ratings (depression or mania) and patient-rated interpersonal relations rating (with parents, siblings or friends) during the 3 months before (t=−3 to −1) and the 3 months after (t=1 to 3) the onset of a depressive or manic episode. PSR ratings were originally recorded in a weekly breakdown, and were converted to monthly scores by using the highest score of a given month to be consistent with interpersonal relations ratings, which reflect worst interactions per month.

PSR1 = Psychiatric Symptom Ratings (depression or mania/hypomania) 3 months prior to month of mood episode onset

PSR2 = PSR 2 months prior to month of mood episode onset

PSR3 = PSR 1 month prior to month of mood episode onset

PSR4 = PSR 1 month after month of mood episode onset

PSR5 = PSR 2 months after month of mood episode onset

PSR6 = PSR 3 months after month of mood episode onset

Intp1 = interpersonal relationship functioning (parents, siblings, friends) 3 months prior to month of mood episode onset

Intp2 = interpersonal relationship functioning 2 months prior to month of mood episode onset

Intp3 = interpersonal relationship functioning 1 month prior to month of mood episode onset

Intp4 = interpersonal relationship functioning 1 month after month of mood episode onset

Intp5 = interpersonal relationship functioning 2 months after month of mood episode onset

Intp6 = interpersonal relationship functioning 3 months after month of mood episode onset

The temporal relationship between interpersonal functioning and mood episode severity was evaluated by comparing the size of the standardized path parameters describing: (1) interpersonal functioning predicting mood episode severity, (2) mood episode severity predicting interpersonal functioning, (3) interpersonal functioning predicting interpersonal functioning, and (4) mood episode severity predicting mood episode severity. The Multiple Imputation (MI) procedure in SAS was used to estimate covariance parameters using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm, which were then used by the test-CALIS (TCALIS) procedure to fit cross-lagged models, a procedure that has been recommended as the current state-of-the-art for dealing with missing data (Schafer and Graham, 2002). An alpha level of .05 was used for all statistical tests.

Results

Participants

Participants were 413 youth (46.5% female), aged 12.6 ± 3.3 years at intake, diagnosed with BP (59.1% BP-I, 4.6% BP-II, 36.3% BP-NOS). The average age of BP episode onset was 9.3 ± 3.9 years. The sample was predominantly White (82.1%) and non-Hispanic (93.7%), with 7.3% of the sample describing themselves as Black, 1.2% Asian, 0.2% Native American, 8.5% biracial, and 0.7% other.

Interpersonal relations and psychiatric symptoms across five years

Descriptive analyses

Descriptive analyses of mood episode severity and interpersonal functioning can be found in Table 4. Interpersonal relationships were generally good, and described as “poor” or worse 11.6% of the time with parents, 17.6% with siblings, and 16.6% with friends. Monthly ratings of interpersonal functioning were more stable than monthly ratings of psychiatric symptoms. The majority of participants reported no or minimal (85.2%-93.3%) change in their interpersonal relationship functioning throughout the study. In contrast, 40.9% (depression) to 35.8% (mania/hypomania) of the participants reported minimal fluctuations in mood symptomatology.

Table 4.

Depression, mania/hypomania, and interpersonal relations over 5-year follow-up

| Mean | SD | Range | Percent of Participants | Average Percent of Time Syndromal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | with SD = 0 | with SD < 1 | M | (SD) | |||

| Depression | 2.55 | (0.92) | 1.06 | (0.44) | 1 - 6 | 5.1 | 40.9 | 14.4 | (18.8) | Depression Severity= 5 or 6 |

| Mania/Hypomania | 2.50 | (0.99) | 1.19 | (0.55) | 1 - 8 | 4.1 | 35.8 | 9.4 | (15.3) | Manic Severity = 5-8 |

| Parents | 2.29 | (0.62) | 0.56 | (0.34) | 1 - 5 | 15.6 | 88.8 | 11.6 | (18.7) | “poor” or “very poor” |

| Siblings | 2.57 | (0.72) | 0.55 | (0.33) | 1 - 5 | 15.5 | 93.3 | 17.6 | (26.1) | “poor” or “very poor” |

| Friends | 2.30 | (0.90) | 0.65 | (0.34) | 1 - 5 | 11.2 | 85.2 | 16.6 | (25.3) | “poor” or “very poor” |

Note: Mean, SD and Percent of Time values were first calculated per person, then averaged across persons

Depression Scale: 1 (no symptoms); 2–4 (subthreshold symptoms and impairment) to 5–6 (full criteria with different degrees of severity or impairment).

Mania Scale: 1 (no symptoms); 2–4 (subthreshold symptoms and impairment); 5-6 (syndromal hypomania); 7-8 (syndromal mania)

Parents/Siblings/Friends scale: 1 (very good), 2 (good), 3 (fair/slightly impaired), 4 (poor/moderately impaired), 5 (very poor/severely impaired).

Between-person correlations

Between-person correlations were cross-sectional and examined whether, across participants, those with more severe mood episode severity also reported poorer interpersonal functioning. Correlations between interpersonal relationships with parents, siblings, and friends were moderate (r = 0.28-.38). Correlations examining the association between mood episode severity and interpersonal relationships between persons were all significant (p < 0.05 or p < .01), albeit moderate to small (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Between-person correlations

| Depression | Mania | Parents | Siblings | Friends | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 1.00 | ||||

| Mania | 0.44 ** | 1.00 | |||

| Parents | 0.27 ** | 0.28 ** | 1.00 | ||

| Siblings | 0.18 ** | 0.12 * | 0.38 ** | 1.00 | |

| Friends | 0.31 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.28 ** | 1.00 |

Note:

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Within-person correlations

Within-person correlations examined whether fluctuations in mood episode severity preceded fluctuations in relationship functioning, and vice versa, over time for each individual participant. Two potential moderators of this relationship, age and comorbid externalizing disorders, were identified a priori. Neither of these variables was significant; results are presented based on a model without moderators. Table 6 describes the within-person correlations across 5.1 years.

Table 6.

Temporal correlations between depression and mania/hypomania severity ratings and patient-rated quality of interpersonal relationships

| Relationship | Depression | Mania/Hypomania | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lag | ||||||||||

| range | range | |||||||||

| mean | (SD) | min | max | mean | (SD) | min | max | |||

| Parents (based on n=336 with variance in both variables) | (based on n=337) | |||||||||

| −2 | 0.09 | (0.29) | −0.69 | - | 0.79 | 0.08 | (0.30) | −0.76 | - | 0.94 |

| −1 | 0.12 | (0.30) | −0.73 | - | 0.84 | 0.10 | (0.32) | −0.78 | - | 0.94 |

| 0 | 0.15 | (0.32) | −0.66 | - | 1.00 | 0.14 | (0.36) | −0.93 | - | 0.98 |

| 1 | 0.13 | (0.31) | −0.69 | - | 0.87 | 0.12 | (0.34) | −0.90 | - | 0.87 |

| 2 | 0.11 | (0.28) | −0.70 | - | 0.80 | 0.10 | (0.30) | −0.77 | - | 0.85 |

| Siblings (based on n=296 with variance in both variables) | (based on n=293) | |||||||||

| −2 | 0.06 | (0.32) | −0.84 | - | 1.00 | 0.06 | (0.30) | −0.73 | - | 0.84 |

| −1 | 0.07 | (0.33) | −0.85 | - | 1.00 | 0.07 | (0.32) | −0.78 | - | 0.92 |

| 0 | 0.08 | (0.34) | −0.86 | - | 1.00 | 0.09 | (0.34) | −0.84 | - | 0.99 |

| 1 | 0.08 | (0.32) | −0.83 | - | 1.00 | 0.08 | (0.33) | −0.82 | - | 0.94 |

| 2 | 0.07 | (0.30) | −0.76 | - | 1.00 | 0.07 | (0.31) | −0.86 | - | 0.86 |

| Friends (based on n=392 with variance in both variables) | (based on n=395) | |||||||||

| −2 | 0.09 | (0.27) | −0.72 | - | 0.77 | 0.07 | (0.30) | −0.81 | - | 0.88 |

| −1 | 0.11 | (0.29) | −0.72 | - | 0.84 | 0.08 | (0.32) | −0.85 | - | 0.92 |

| 0 | 0.13 | (0.30) | −0.72 | - | 0.94 | 0.09 | (0.35) | −0.92 | - | 0.96 |

| 1 | 0.12 | (0.28) | −0.73 | - | 0.84 | 0.07 | (0.32) | −0.87 | - | 0.93 |

| 2 | 0.09 | (0.26) | −0.73 | - | 0.79 | 0.06 | (0.29) | −0.82 | - | 0.91 |

Key Table 2:

Lag −2: mood episode severity (e.g., depression and mania/hypomania) from two months ago predicting this month's interpersonal relationships (e.g., parents, siblings, friends)

Lag −1: last month's mood episode severity predicting this month's interpersonal relationships

Lag 0: correlation between this month's mood episode severity and this month's interpersonal relationships

Lag 1: last month's interpersonal relationships predicting this month's mood episode severity

Lag 2: interpersonal relationships from two months ago predicting this month's mood episode severity

Correlations could only be calculated for participants who had variance in both variables (see Table 6). The highest within-person correlations were observed for relations with parents, where the concurrent correlation of ratings for parents was 0.15 with depression and 0.14 with mania. For the relationships between mood episode severity and interpersonal functioning, lagged correlations (i.e. correlations between two variables at different time points) were smaller than concurrent correlations (i.e. correlations between two variables at the same time point). We conducted paired t-tests to compare lagged correlations, which examined the relationship between episode severity and interpersonal relationships as observed at different time points, to one another. T-tests indicated that last month's relations with parents were more strongly correlated with this month's depression (t(335)=2.16, p<.05) and mania (t(336)=1.99, p<.05) ratings than last month's mood episode ratings with this month's relations with parents.

No statistically significant differences were found for siblings or friends.

Interpersonal relations and mood episode severity around onset of syndromal depression/mania

The next set of analyses examined longitudinal correlations between interpersonal functioning and mood episode severity around the onset of syndromal depression and mania/hypomania (see Figure 1). Onset of a mood episode was operationalized as scores of PSR 5-6 for depression and 5-8 for mania/hypomania, after at least eight consecutive weeks of PSR 1. During the course of the study 55.4% (n=229) of participants experienced an onset of a depressive episode and 33.2% (n=137) experienced an onset of a manic/hypomanic episode. The month of episode onset is analyzed as month 0, with the month preceding onset as −1, the month following as +1, etc. for three months preceding and following onset. For participants who experienced multiple onsets of syndromal depressive or manic episodes, the first observed onset was used, unless it occurred within 3 months of intake, in which case the second observed onset was used, so that data during the 3 months preceding onset were included in the analyses.

Onset of a depressive episode

The fit of all three cross-lagged models around the onset of a depressive episode was very good, with χ2(40)=37.95, p=0.52, CFI=1.00 and RMSEA=0.00 for parents, χ2(40)=57.27, p<0.05, CFI=0.99 and RMSEA=0.05 for friends, and χ2(40)=58.91, p<0.05, CFI=0.98 and RMSEA=0.06 for siblings. All stability paths (i.e., depression predicting depression, etc.) were statistically significant (Table 7), and were extremely high for interpersonal relations (standardized parameter estimates ranging from 0.71 to 0.96), indicating that interpersonal functioning remained stable preceding and following depressive episode onset. Cross-lagged parameter estimates were rarely significant and had low standardized parameter estimates (i.e., < 0.15), indicating that changes in mood episode severity did not predict changes in interpersonal functioning preceding and following depressive episode onset.

Table 7.

Standardized path parameters of the cross-lagged models around the onset of depression (n=229 experienced onset of depression)

| Temporal Relationship | Parents (n=229) | Siblings (n=196) | Friends (n=229) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | EST | SE | t | EST | SE | t | EST | SE | t | |||||

| Depression predicting interpersonal relationships | ||||||||||||||

| dep1 | → | intp2 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.87 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.42 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | |||

| dep2 | → | intp3 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.47 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.46 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.17 | |||

| dep3 | → | intp4 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.10 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −1.06 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 1.91 | |||

| dep4 | → | intp5 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.40 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.14 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1.03 | |||

| dep5 | → | intp6 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.55 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 2.20 | * | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.36 | ||

| Interpersonal relationships predicting depression | ||||||||||||||

| intp1 | → | dep2 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 2.82 | * | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.32 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.14 | ||

| intp2 | → | dep3 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.30 | |||

| intp3 | → | dep4 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 1.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.56 | |||

| intp4 | → | dep5 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 1.60 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 2.47 | * | ||

| intp5 | → | dep6 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.84 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.40 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.18 | |||

| Depression predicting depression | ||||||||||||||

| dep1 | → | dep2 | 0.66 | 0.04 | 17.88 | * | 0.67 | 0.04 | 17.80 | * | 0.68 | 0.04 | 19.07 | * |

| dep2 | → | dep3 | 0.63 | 0.04 | 14.65 | * | 0.63 | 0.04 | 14.84 | * | 0.63 | 0.04 | 15.73 | * |

| dep3 | → | dep4 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 3.31 | * | 0.22 | 0.07 | 3.29 | * | 0.22 | 0.06 | 3.48 | * |

| dep4 | → | dep5 | 0.41 | 0.06 | 7.22 | * | 0.42 | 0.06 | 7.27 | * | 0.40 | 0.06 | 7.10 | * |

| dep5 | → | dep6 | 0.66 | 0.04 | 16.86 | * | 0.67 | 0.04 | 17.29 | * | 0.67 | 0.04 | 17.40 | * |

| Interpersonal relationships predicting interpersonal relationships | ||||||||||||||

| intp1 | → | intp2 | 0.92 | 0.01 | 81.20 | * | 0.93 | 0.01 | 94.42 | * | 0.93 | 0.01 | 110.62 | * |

| intp2 | → | intp3 | 0.94 | 0.01 | 83.10 | * | 0.92 | 0.01 | 85.98 | * | 0.96 | 0.00 | 203.11 | * |

| intp3 | → | intp4 | 0.71 | 0.03 | 20.67 | * | 0.87 | 0.02 | 48.77 | * | 0.78 | 0.03 | 29.05 | * |

| intp4 | → | intp5 | 0.84 | 0.02 | 41.52 | * | 0.90 | 0.01 | 65.05 | * | 0.90 | 0.01 | 69.04 | * |

| intp5 | → | intp6 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 65.28 | * | 0.93 | 0.01 | 97.09 | * | 0.90 | 0.01 | 66.70 | * |

Note: Not all participants had a sibling.

Key Table 7:

dep1/mania1 – mood episode severity (depression or mania/hypomania) 3 months prior to month of mood episode onset

dep2/mania2 – mood episode severity 2 months prior to month of mood episode onset

dep3/mania3 – mood episode severity 1 month prior to month of mood episode onset

dep4/mania4 – mood episode severity 1 month after month of mood episode onset

dep5/mania5 – mood episode severity 2 months after month of mood episode onset

dep6/mania6 – mood episode severity 3 months after month of mood episode onset

intp1 – interpersonal relationships (parents, siblings, friends) 3 months prior to month of mood episode onset

intp2 – interpersonal relationships 2 months prior to month of mood episode onset

intp3 – interpersonal relationships 1 month prior to month of mood episode onset

intp4 – interpersonal relationships 1 month after month of mood episode onset

intp5 – interpersonal relationships 2 months after month of mood episode onset

intp6 – interpersonal relationships 3 months after month of mood episode onset

Onset of a manic/hypomanic episode

The fit of the cross-lagged models around the onset of a manic/hypomanic episode was very good for parents ( χ2(40)=58.91, p<0.05, CFI=0.98 and RMSEA=0.06) and friends (χ2(40)=44.31, p=0.29, CFI=1.00 and RMSEA=0.03). For siblings (χ2(40)=71.52, p<0.05, CFI=0.97 and RMSEA=0.08), the CFI indicated good fit. Not all parameter estimates were significant (Table 8). Most stability paths were statistically significant except for prediction of mania onset from prior month mania ratings. All other stability parameter estimates were extremely high for interpersonal relations (standardized parameter estimates ranging from 0.78 to 0.95), indicating that interpersonal functioning remained stable around the onset of a manic/hypomanic episode. Cross-lagged parameter estimates were rarely significant and had low standardized parameter estimates (i.e., < 0.14). Therefore, changes in mood episode severity around the onset of a mania/hypomania episode did not predict changes in interpersonal functioning.

Table 8.

Standardized path parameters of the cross-lagged models around the onset of mania/hypomania (n= 137 experienced onset of mania/hypomania)

| Temporal Relationship | Parents (n=137) | Siblings (n=115) | Friends (n=137) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | EST | SE | t | EST | SE | t | EST | SE | t | |||||

| Mania/hypomania predicting interpersonal relationships | ||||||||||||||

| mania1 | → | intp2 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.4 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.3 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.5 | |||

| mania2 | → | intp3 | −0.13 | 0.05 | −2.7 | * | −0.08 | 0.04 | −2.0 | * | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.4 | |

| mania3 | → | intp4 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.9 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.2 | |||

| mania4 | → | intp5 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.3 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.3 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.8 | |||

| mania5 | → | intp6 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −1.0 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −1.3 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −1.2 | |||

| Interpersonal relationships predicting mania/hypomania | ||||||||||||||

| intp1 | → | mania2 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.1 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 1.8 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −1.0 | |||

| intp2 | → | mania3 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 1.1 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.5 | |||

| intp3 | → | mania4 | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.4 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 1.2 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 1.0 | |||

| intp4 | → | mania5 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 1.4 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.1 | −0.11 | 0.08 | −1.4 | |||

| intp5 | → | mania6 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.4 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.8 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 1.8 | |||

| Mania/hypomania predicting mania/hypomania | ||||||||||||||

| mania1 | → | mania2 | 0.78 | 0.04 | 22.1 | * | 0.75 | 0.04 | 18.9 | * | 0.77 | 0.03 | 22.3 | * |

| mania2 | → | mania3 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 17.5 | * | 0.73 | 0.04 | 16.3 | * | 0.73 | 0.04 | 18.0 | * |

| mania3 | → | mania4 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.1 | |||

| mania4 | → | mania5 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 2.9 | * | 0.24 | 0.09 | 2.9 | * | 0.25 | 0.08 | 3.2 | * |

| mania5 | → | mania6 | 0.49 | 0.07 | 7.4 | * | 0.49 | 0.07 | 7.2 | * | 0.51 | 0.06 | 7.9 | * |

| Interpersonal relationships predicting interpersonal relationships | ||||||||||||||

| intp1 | → | intp2 | 0.91 | 0.02 | 56.7 | * | 0.92 | 0.02 | 57.0 | * | 0.94 | 0.01 | 92.5 | * |

| intp2 | → | intp3 | 0.84 | 0.03 | 31.3 | * | 0.91 | 0.02 | 46.1 | * | 0.95 | 0.01 | 101.6 | * |

| intp3 | → | intp4 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 23.6 | * | 0.92 | 0.01 | 69.4 | * | 0.92 | 0.01 | 73.7 | * |

| intp4 | → | intp5 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 25.5 | * | 0.85 | 0.03 | 32.3 | * | 0.88 | 0.02 | 45.7 | * |

| intp5 | → | intp6 | 0.89 | 0.02 | 45.0 | * | 0.82 | 0.03 | 28.1 | * | 0.94 | 0.01 | 89.9 | * |

Note: Not all participants had a sibling.

p < 0.05

Key Table 8:

dep1/mania1 – mood episode severity (depression or mania/hypomania) 3 months prior to month of mood episode onset

dep2/mania2 – mood episode severity 2 months prior to month of mood episode onset

dep3/mania3 – mood episode severity 1 month prior to month of mood episode onset

dep4/mania4 – mood episode severity 1 month after month of mood episode onset

dep5/mania5 – mood episode severity 2 months after month of mood episode onset

dep6/mania6 – mood episode severity 3 months after month of mood episode onset

intp1 – interpersonal relationships (parents, siblings, friends) 3 months prior to month of mood episode onset

intp2 – interpersonal relationships 2 months prior to month of mood episode onset

intp3 – interpersonal relationships 1 month prior to month of mood episode onset

intp4 – interpersonal relationships 1 month after month of mood episode onset

intp5 – interpersonal relationships 2 months after month of mood episode onset

intp6 – interpersonal relationships 3 months after month of mood episode onset

Discussion

The current study examined the association between mood episode severity and interpersonal functioning in a large sample of BP youth over the course of an average of 5.1 ± 1.8 years of follow-up. Results indicated that participants with greater mood episode severity also had worse relationships. Longitudinally, participants had largely stable relationships. To the extent that there were associations, changes in parental relationships may precede changes in mood episode severity, although the magnitude of this finding was small.

Consistent with previous research and with our expectations, those with a less severe BP course reported significantly better interpersonal functioning (Geller et al., 2002, Geller et al., 2004, Johnson et al., 2003). This is supported by findings that between-person correlations were much stronger than within-person correlations, suggesting that the relationship between these variables is likely to be more specific to the individual, rather than consistent across all participants. Within-person, longitudinal correlations were comparatively small, partially because interpersonal functioning remained somewhat stable over the course of the study. While mood episode severity fluctuated, relationships with parents, friends, and siblings had very little fluctuation, even during the onset of mood episodes. Of note, the design and strength of the measure of interpersonal functioning (PFS) is to capture large, clinically meaningful changes in interpersonal functioning over time (e.g., DelBello et al., 2007; Goldstein et al., 2009; Keller et al., 1987; Leon et al., 1999; Leon et al., 2000; Miklowitz et al., 2007; Philips et al., 2006). Thus, it is not intended to measure subtle changes in interpersonal functioning, which might be one reason for the observed stability.

Stability was not due to poor interpersonal relationships. In fact, participants described the relationships as “poor” or worse only 11.6%-17.6% of the time. Although not specifically examined in the current study, one possible explanation for this stability might be that as friends and family members grow accustomed to symptoms and gain more knowledge about BP, relationships might become less affected by mood changes. The factors contributing to relationship stability in BP youth would be an interesting and important area for future research.

While interpersonal relationships were stable overall, evidence suggested that changes in interpersonal functioning might precede changes in mood episode severity. Specifically, the correlations in which parental relationships preceded mood episode severity were significantly larger than the correlations in which mood episode severity preceded parental relationships. However, the difference between these correlations was small and, thus, this finding is very tentative and would require replication. Nevertheless, findings suggest that relationships with parents may have a longitudinal impact on future mood episodes. Previous research has similarly found difficulties with interpersonal functioning to predict changes in depression over time in adults with BP (Johnson et al., 2000, Johnson et al., 1999, Weinstock and Miller, 2008, Yan et al., 2004). This finding suggests areas for future research, including exploring the components of parental relationships that impact mood episode severity, how long these effects might last, and what types of relationship changes might lead to mood improvements.

Analyses that examined the onset of a mood episode indicate that changes in mood episode severity did not significantly impact interpersonal functioning. This was contrary to our expectations of a bi-directional relationship between mood episode severity and interpersonal relationship functioning. This might be because in the months preceding a mood episode, youth experienced subsyndromal symptoms but did not yet meet full criteria for a mood episode. In fact, a previous study examining the four-year course of illness in the COBY study (Birmaher et al., 2009a) found that youth spent 16.6% of the follow-up time experiencing syndromal episodes and 41.8% of the time experiencing subsyndromal symptoms.

Within-person correlations also exhibited wide variability between participants. Some individuals had strong associations between mood episode severity and interpersonal functioning over time, while others exhibited a very weak association. Both positive and negative correlations were observed. Two moderators identified a priori were examined, age and comorbid externalizing disorders. Neither of these moderators explained the wide variation in within-person correlations. Individual differences might be attributed to many factors such as sex, BP subtypes, SES, comorbid disorders, and treatment utilization. While the purpose of the current study was to examine temporal associations, examining these factors, would be an interesting and important focus for future research.

Limitations

Results of the current study contribute to our knowledge of interpersonal relationships in BP youth. Nevertheless, some limitations should be considered. First, despite efforts to obtain precise information, the data collected through the ALIFE (via a method similar to TLFB) are subject to retrospective recall bias. Nevertheless, TLFB is a gold-standard, and has been used extensively for over 30 years in clinical and nonclinical research studies (Sobell, 2008). Second, summary scores combining parent- and youth-report of interpersonal functioning were used. It would be important for future research to examine parent- and youth-reports of interpersonal relationships separately to determine whether they may have differential associations with symptoms. Third, interpersonal functioning was assessed using a global measure, designed to capture large, clinically meaningful changes. Specific qualities of relationships (e.g., expressed emotion, social support) or more subtle changes in relationship functioning may have specific temporal associations with mood symptoms, an important area for future research. Fourth, the stability in interpersonal functioning scores may be a function of our measurement approach, in which relationships within categories (i.e., parents, siblings, friends) were necessarily collapsed to facilitate analyses, thus losing variability experienced within a specific type of relationship. Fifth, mixed symptoms and episodes were not examined, for reasons outlined above. Future research might examine mixed symptoms/episodes and interpersonal functioning in BP youth. Sixth, the majority of the sample was White, limiting the generalizability of study results to more diverse populations. Future research examining interpersonal relationships in BP youth would benefit from utilizing more diverse samples.

Despite these limitations, the current study has many strengths. The large sample size, long duration of follow-up assessments, frequency with which participants were assessed, and demonstrated reliability and validity of the methods used are all unique and important strengths. Examining the interplay between interpersonal relationships and mood episode severity longitudinally increases our understanding of their dynamic relationship and provides insight into their putative causal relationship. Findings from the current study have the potential to inform treatment and provide a framework for future studies to further examine this important area.

Conclusions

Findings from the current study indicate that participants with greater episode severity also had poorer relationships with family and peers. Correlations examining the association between mood episode severity and interpersonal relationship functioning within persons were small, due to the fact that relationships were stable over the follow-up period. Longitudinal analyses suggested that changes in parental relationships may precede changes in episode severity, although the magnitude of this finding was small. Overall, participants had stable relationships that were not significantly impacted by episode severity.

Results from the current study have important clinical implications. If BP youth have good, stable relationships even during mood episodes, treatment can help youth utilize social supports to cope with symptoms. Findings indicated that individuals with better interpersonal functioning exhibited a less severe course of illness. Additionally, results suggest that interpersonal functioning may predict mood episode severity more so than vice versa. Thus, interventions focused on improving family functioning (Miklowitz et al., 2004) and peer relationships might be effective in reducing mood symptoms. These findings are also of importance for parents when helping youth manage mood symptoms. There might be utility in tracking mood symptoms alongside any changes in interpersonal relationship functioning, such as through paper or web-based mood/functioning calendars (Strejilevich et al., 2013). This might help youth and their families to develop greater insight into symptom patterns and their relationship with changes in interpersonal functioning, and can also be shared with providers to assist in implementing interventions.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: Thanks to the families for their participation, the COBY research staff, and Shelli Avenevoli Ph.D. from the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) for their support. This paper was supported by NIMH grants MH59691 (to Drs. Keller/Yen), MH059929 (to Dr. Birmaher), and MH59977 (to Dr. Strober), and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant K01DA027097 (Dr. Hoeppner).

All authors except Dr. Siegel receive research support from the NIMH for the submitted work, as noted above. Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work are as follows: Dr. Siegel has received research support from the NIMH. Dr. Stout is employed at the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation (PIRE), and receives research support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), NIDA, and NIMH. Dr. Weinstock receives research support from NIMH and the Depressive and Bipolar Disorder Alternative Treatment Foundation (DBDAT). Dr. Birmaher is employed at the University of Pittsburgh/University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), receives research support from NIMH and the McGuinn Foundation, and receives royalties from Random House, Inc., and Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Dr. T. Goldstein is employed at the University of Pittsburgh/UPMC, receives research support from NIMH, NIDA, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the Pittsburgh Foundation, receives royalties from Guilford Press, and receives travel/accommodations/meeting expenses from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP). Dr. B. Goldstein was a consultant for BMS, and has received payment for lectures including service on speakers bureaus from Purdue Pharma. Dr. Hunt is a senior editor of Brown Child and Adolescent psychopharmacology update, and receives honoraria from Wiley Publishers. Dr. Strober receives support from the Resnick Endowed Chair in Eating Disorders. Dr. Keller has received research support from Pfizer.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

For the remaining authors, no other relevant financial activities outside the submitted work were declared.

For contextual purposes, an 8 on the integrated scale is equivalent to a PSR 6 on the traditional PSR scale (full threshold mania).

Comparative analyses were conducted for all statistical tests, where “6” was coded as “3”, which resulted in the same findings.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Bridge J, Keller M. Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1139–48. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Strober MA, Goldstein BI, Ha W, Gill MK, Goldstein TR, Yen S, Hower H, Hunt JI, Liao F, Iyengar S, Dickstein D, Kim E, Ryan ND, Frankel E, Keller MB. Course of subthreshold bipolar disorder in youth: diagnostic progression from bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:1001–16. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardinelli C, Hatch JP, Olvera RL, Fonseca M, Caetano SC, Nicoletti M, Pliszka S, Soares JC. Family environment patterns in families with bipolar children. J Affect Disord. 2008;107:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, Strober M, Gill MK, Hunt J, Houck P, Ha W, Iyengar S, Kim E, Yen S, Hower H, Esposito-Smythers C, Goldstein T, Ryan N, Keller M. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009a;166:795–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08101569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Keller M. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:175–83. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Yang M, Ryan N, Goldstein B, Hunt J, Esposito-Smythers C, Iyengar S, Goldstein T, Chiapetta L, Keller M, Leonard H. Comparison of manic and depressive symptoms between children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2009b;11:52–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00659.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: BOLLON KAL, J.S., editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chango JM, McElhaney KB, Allen JP, Schad MM, Marston E. Relational stressors and depressive symptoms in late adolescence: Rejection sensitivity as a vulnerability. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40:369–379. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9570-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Goldberg A. Romantic relationships in adolescence: The role of friends and peers in their emergence and development. In: Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1999. pp. 266–290. [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP, Hanseman D, Adler CM, Fleck DE, Strakowski SM. Twelve-month outcome of adolescents with bipolar disorder followign first hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:582–590. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erath SA, Flanagan KS, Bierman KL, Tu KM. Friendships moderate psychosocial maladjustment in socially anxious early adolescents. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito-Smythers C, Birmaher B, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Hunt J, Ryan N, Axelson D, Strober M, Leonard H, Sindelar H, Keller M. Child comorbidity, maternal mood disorder, and perceptions of family functioning among bipolar youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:955–64. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000222785.11359.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children's perceptions of the qualities of sibling relationships. Child Dev. 1985;56:448–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, Williams M, Delbello MP, Gundersen K. Psychosocial functioning in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1543–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200012000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Craney JL, Bolhofner K, Nickelsburg MJ, Williams M, Zimerman B. Two-year prospective follow-up of children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:927–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Tillman R, Craney JL, Bolhofner K. Four-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:459–67. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JF, Harrow M. Subjective life satisfaction and objective functional outcome in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders: a longitudinal analysis. J Affect Disord. 2005;89:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein BI, Gill MK, Esposito-Smythers C, Ryan ND, Strober MA, Hunt J, Keller M. Psychosocial functioning among bipolar youth. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:174–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW. The company they keep: friendships and their developmental significance. Child Dev. 1996;67:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hower H, Case BG, Hoeppner B, Yen S, Goldstein T, Goldstein B, Birmaher B, Weinstock L, Topor D, Hunt J, Strober M, Ryan N, Axelson D, Kay Gill M, Keller MB. Use of mental health services in transition age youth with bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19:464–76. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000438185.81983.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L-T, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Perceived peer context and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10:391–415. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Prospective analysis of comorbidity: tobacco and alcohol use disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:679–94. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L, Lundstrom O, Aberg-Wistedt A, Mathe AA. Social support in bipolar disorder: its relevance to remission and relapse. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:129–37. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Meyer B, Winett C, Small J. Social support and self-esteem predict changes in bipolar depression but not mania. J Affect Disord. 2000;58:79–86. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Winett CA, Meyer B, Greenhouse WJ, Miller I. Social support and the course of bipolar disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108:558–66. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, Mcdonald-Scott P, Andreasen NC. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation. A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kia-Keating M, Dowdy E, Morgan ML, Noam GG. Protecting and promoting: an integrative conceptual model for healthy development of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:220–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Miklowitz DJ, Biuckians A, Mullen K. Life stress and the course of early-onset bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;99:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent Peer Relations, Friendships, and Romantic Relationships: Do They Predict Social Anxiety and Depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. doi: 10. 1207/s15374424jccp3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Solomon DA, Mueller TI, Endicott J, Posternak M, Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, Keller MB. A brief assessment of psychosocial functioning of subjects with bipolar I disorder: the LIFE-RIFT. Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation-Range Impaired Functioning Tool. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:805–12. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200012000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Solomon DA, Mueller TI, Turvey CL, Endicott J, Keller MB. The Range of Impaired Functioning Tool (LIFE-RIFT): a brief measure of functional impairment. Psychol Med. 1999;29:869–78. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis AD, Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, Beardslee WR, Ward KE, Fitzmaurice GM. Adolescent family factors promoting healthy adult functioning: A longitudinal community study. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2011;16:30–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2010.00577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Roy K, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K, Malhi G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. Atypical depression: A reappraisal. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1470–1479. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, George EL, Axelson DA, Kim EY, Birmaher B, Schneck C, Beresford C, Craighead WE, Brent DA. Family-focused treatment for adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004;82(Suppl 1):S113–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Reilly-Harrington NA, Kogan JN, Sachs GS, Thase ME, Calabrese JR, Marangell LB, Ostacher MJ, Patel J, Thomas MR, Araga M, Gonzalez JM, Wisniewski SR. Intensive psychosocial intervention enhances functioning in patients with bipolar depression: results from a 9-month randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1340–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07020311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, Bagwell CL. Children's friendship relations: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:306–347. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini D, Kosisky S, Nackman D, Cytryn L, Mcknew DH, Gershon E, Hamovit J, Cammuso K. Personal and social resources in children of patients with bipolar affective disorder and children of normal control subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:856–61. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.7.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Didie ER, Menard W, Pagano ME, Fay C, Weisberg RB. Clinical features of body dysmorphic disorder in adolescents and adults. Psychiatry Res. 2006;141:305–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:147–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel LS, West AE, Harral EM, Patel NB, Pavuluri MN. Parent-child interactions in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64:422–37. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol Timeline Followback (TLFB) American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C.: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Strejilevich SA, Martino DJ, Murru A, Teitelbaum J, Fassi G, Marengo E, Igoa A, Colom F. Mood instability and functional recovery in bipolar disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;128:194–202. doi: 10.1111/acps.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan AE, Judd CM, Axelson DA, Miklowitz DJ. Family functioning and the course of adolescent bipolar disorder. Behav Ther. 2012;43:837–47. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan AE, Miklowitz DJ. Family functioning among adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Fam Psychol. 2010;24:60–7. doi: 10.1037/a0018183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uebelacker LA, Beevers CG, Battle CL, Strong D, Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Solomon DA, Miller IW. Family functioning in bipolar I disorder. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20:701–4. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw MG, Dyck I, Allsworth J, Stout RL, Keller MB. Maintaining reliability in a long-term psychiatric study: An ongoing inter-rater reliablity monitoring program using the longitudinal follow-up evaluation. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2001;35:297–305. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock LM, Miller IW. Functional impairment as a predictor of short-term symptom course in bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:437–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingo AP, Baldessarini RJ, Compton MT, Harvey PD. Correlates of recovery of social functioning in types I and II bipolar disorder patients. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177:131–4. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan LJ, Hammen C, Cohen AN, Daley SE, Henry RM. Expressed emotion versus relationship quality variables in the prediction of recurrence in bipolar patients. J Affect Disord. 2004;83:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngblade LM, Theokas C, Schulenberg J, Curry L, Huang IC, Novak M. Risk and protective factors in families, schools, and communities: A contextual model of positive youth development in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2007;119:S47, 547–553. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]