Abstract

Medical professionalism has become a core topic in medical education. As it has been considered mostly from a Western perspective, there is a need to examine how the same or similar concepts are reflected in a wider range of cultural contexts. To gain insights into medical professionalism concepts in Japanese culture, the authors compare the tenets of a frequently referenced Western guide to professionalism (the physician charter proposed by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, American College of Physicians Foundation, and the European Federation of Internal Medicine) with the concepts of Bushido, a Japanese code of personal conduct originating from the ancient samurai warriors. The authors also present survey evidence about how a group of present-day Japanese doctors view the values of Bushido.

Cultural scholars have demonstrated Bushido’s continuing influence on Japanese people today. The authors explain the seven main virtues of Bushido (e.g., rectitude), describe the similarities and differences between Bushido and the physician charter, and speculate on factors that may account for the differences, including the influence of religion, how much the group versus the individual is emphasized in a culture, and what emphasis is given to virtue-based versus duty-based ethics.

The authors suggest that for those who are teaching and practicing in Japan today, Bushido’s virtues are applicable when considering medical professionalism and merit further study. They urge that there be a richer discussion, from the viewpoints of different cultures, on the meaning of professionalism in today’s health care practice.

Medical professionalism has recently become a core topic in medical education,1 which is reflected in a growing body of literature discussing curriculum development, teaching, and the evaluation of professionalism in physicians’ development.2 The physician charter proposed by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, American College of Physicians Foundation, and the European Federation of Internal Medicine3–5 is frequently cited as an authoritative document about professionalism. The charter’s 3 principles (primacy of patient welfare, patient autonomy, and social justice) and 10 professional commitments5 are widely endorsed by international professional associations, colleges, societies, and certifying boards. However, we believe that the discussion of professionalism should also be related to the world’s different cultures and social contracts, respecting local customs and values even when they differ from Western ones.6 This is because the role of the physician is subject to cultural differences and dependent on the nature of the particular health care system in which medicine is practiced.6 As medical professionalism has mostly been considered from a Western perspective, there is a need to examine how the same, similar, or even different concepts are reflected in a wider range of cultural contexts.7

In Japan, professionalism is being discussed in a variety of forums, such as the Professionalism Committee of the Japanese Society of Medical Education and the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine.8 Questions have been raised about how to translate the mostly Western concepts of professionalism presented in international publications into the Japanese setting as well as how to tell the international community about unique Japanese concepts relating to medical professionalism. The very term professionalism, whose first meaning is “the conduct, aims, or qualities that characterize or mark a profession or a professional person,”9(p930) largely reflects a Western concept; there is no corresponding word in most Asian languages, including Japanese.10

To describe the views of some Japanese doctors on professionalism-related concepts, we have chosen Bushido as a value system, because it has much in common with Western virtue ethics; its meaning, “the way of the warrior,” is comparable to that of professionalism. It is a historical Japanese code of personal conduct originating from the ancient samurai warriors. In this article, we introduce the concepts of Bushido, compare them with Western concepts of medical professionalism—as represented by the physician charter mentioned earlier—and present views of some doctors now working in Japan about the continuing relevance (and occasional nonrelevance) of Bushido to their medical practices.

The Concepts of Bushido

Background

Although there are many books written about Bushido, the one by Inazo Nitobe,11 Bushido: The Soul of Japan, published in English in 1900, is a classic that is highly referenced in the international community. Nitobe describes Bushido as the code of moral principles that the knights (samurais) were required or instructed to observe. It is likened to chivalry and the noblesse oblige of the ancient warrior class of Europe. As in the martial arts of judo or karate, Bushido has a basis in Buddhism, Confucianism, and Shintoism.12 Though some cultural experts and scholars argue that the influence of Bushido on Japanese society has lessened,13 others say that the spirit of Bushido remains in the minds and hearts of the Japanese people.9,14 Although Bushido is not specific to medicine, some argue that it continues to influence the behavior of modern Japanese doctors.15

The seven principal virtues

The seven principal virtues in Bushido are rectitude (gi), courage (yu), benevolence (jin), politeness (rei), honesty (sei), honor (meiyo), and loyalty (chugi). Below, we describe each virtue in more detail. We have presented the virtues in the order given by Nitobe.

The first virtue, rectitude (gi), is considered the most fundamental virtue of the samurai. It is the way of thinking, deciding, and behaving in accordance with reason, without wavering. In a medical setting, this guides the doctor to what she or he should be doing; therefore, it is analogous to the concept of professionalism itself. It is also similar to the concept of altruism, as rectitude is usually meant as the antonym of seeking personal benefit. Furthermore, because the same Chinese character is used for rectitude and justice in Japanese writing, the concept of rectitude is also tied in with the concept of social justice. In an e-mailed survey of Japanese doctors that we carried out in 2012,* 117 of the 133 respondents (88%) agreed (by answering “strongly agree” or “agree”) that gi exists in their daily practices. Representative comments are “It is the value of justice or morality for doctors,” “I have sacrificed my private life because I am a doctor (so there is gi in me),” and “I would not work as a hospital doctor if I pursued financial benefit.”

Courage (yu), the second virtue, meaning the spirit of daring and bearing (i.e., how one stands, walks, and behaves), is defined as doing what is right in the face of danger. In Bushido, the concept that righteous action speaks louder than words is highly valued. Whilst there is no analogous concept in the physician charter, yu can be understood to mean being unafraid to put the principles of professionalism into practice. Eighty-three respondents (62%) agreed to the existence of this virtue in their daily practices. Representative comments are “Doctors who went to rescue people suffering from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami are good examples” and “Recently, I find it difficult to practice yu, as patients became more and more demanding.”

The third virtue, benevolence (jin), encompasses the concepts of love, sympathy, and pity for others and is recognized as the highest of all the attributes of the human soul. For doctors, that means practicing “medicine as a benevolent art,” as one respondent to the survey expressed it. The concept of benevolence is expressed as “patient welfare” or “altruism” in the physician charter, though the Bushido concept of jin is more emotional and linked to empathy. In the survey, 123 respondents (93%) agreed that jin is alive in their clinical practices. Representative comments are “Jin is absolutely necessary!!!” and “There is no medical practice without jin.”

Politeness (rei), the fourth virtue, is defined as respectful regard for the feelings of others. Nitobe11 said that rei “suffers long, and is kind; envieth not, vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up; does not behave itself unseemly; seeks not her own; is not easily provoked; takes no account of evil.” Although it may be one of the most influential concepts of the doctor–patient relationship in Japan, politeness is not described in the physician charter. We suggest that it is analogous to a commitment to maintaining appropriate relationships. In the survey, 111 respondents (83%) agreed that rei is important in their clinical practices. Representative comments are “I always try to show rei to patients,” “I cannot do medical practice without rei,” and “We must show rei as a member of society. It is a virtue that goes beyond medicine.”

The Chinese character for honesty (sei) combines the characters for “word” and “perfect.” The phrase bushi no ichi-gon means “the word of a samurai,” which is a guarantee of truth. This fifth virtue is a counterpart to the commitment to honesty in the physician charter, though Bushido places greater emphasis than the charter on spoken words. Therefore, doctors in Japan may be embarrassed when they orally tell something important to patients and then have to change it (which happens in daily clinical practice). In the survey, 94 respondents (71%) agreed that sei is important in their clinical practices. Some representative comments are “In most cases, I tell my patients the truth even though it is a bad news,” “Sei is fundamentally important,” and (a contrasting view) “Sometimes the end justifies the means.”

Honor (meiyo), the sixth virtue, is recognized as the ultimate pursuit of goodness. Nitobe11 wrote, “The sense of meiyo could not fail to characterize the samurai, born and bred to value the duties and privileges of their profession.” By writing that “Death involving a question of meiyo was accepted in Bushido as a key to the solution of many complex problems,” Nitobe tried to explain the meaning of hara-kiri and seppuku; both are the classical types of suicide for samurai. We could draw a parallel with the concept of commitment to professional responsibilities, although there are some clear differences between the two; for example, doctors do not have to kill themselves as a result of unprofessional behavior. In the survey, 86 respondents (65%) agreed that meiyo is important in their clinical practices. Representative comments are “I feel meiyo to be a doctor,” “I do not know.… I do not care much about meiyo, to be honest,” and “Recently, I feel meiyo has lessened.”

In contrast to the individualism of the West, the Japanese have long valued loyalty (chu-gi) to the needs and interests of the group (e.g., family or hospital staff), placing the group’s needs above their own needs and interests. Bushido says that the interests of the family and the interests of its members are inseparable. Indeed, institutional loyalty is one of the factors that has encouraged Japan’s health care workforce to display values of altruism in patient care. Yet in the survey, only 62 respondents (47%) agreed that chu-gi is important in their clinical practices. Representative comments are “I feel chu-gi to my boss and the hospital I am working for,” “I weigh my personal benefit against the institutional one where I belong,” and “Recently, I feel fewer and fewer doctors feel chu-gi.”

Comparing Bushido and the Physician Charter

By comparing Bushido with the physician charter, we found that there are omissions, nuances, and blendings of words that create differences between the two in addition to the differences that are clearly there, which reminds us how meanings can be altered in translation and interpretation. Nevertheless, comparisons of Bushido and the physician charter can provide fresh insights into the understanding of professionalism. The charter calls for altruism from doctors, a concept that has a long tradition in Western thought.16 The Japanese way of upholding the primacy of patient welfare is to practice a blend of rectitude, benevolence, and loyalty. Similarly, although the concept of social justice per se may not prevail in the Japanese health care system, the concepts of rectitude, honor, and loyalty together represent social justice. For example, when these virtues work together within a universal health care system (i.e., one that covers everyone), they can motivate physicians to eliminate discrimination in health care.17

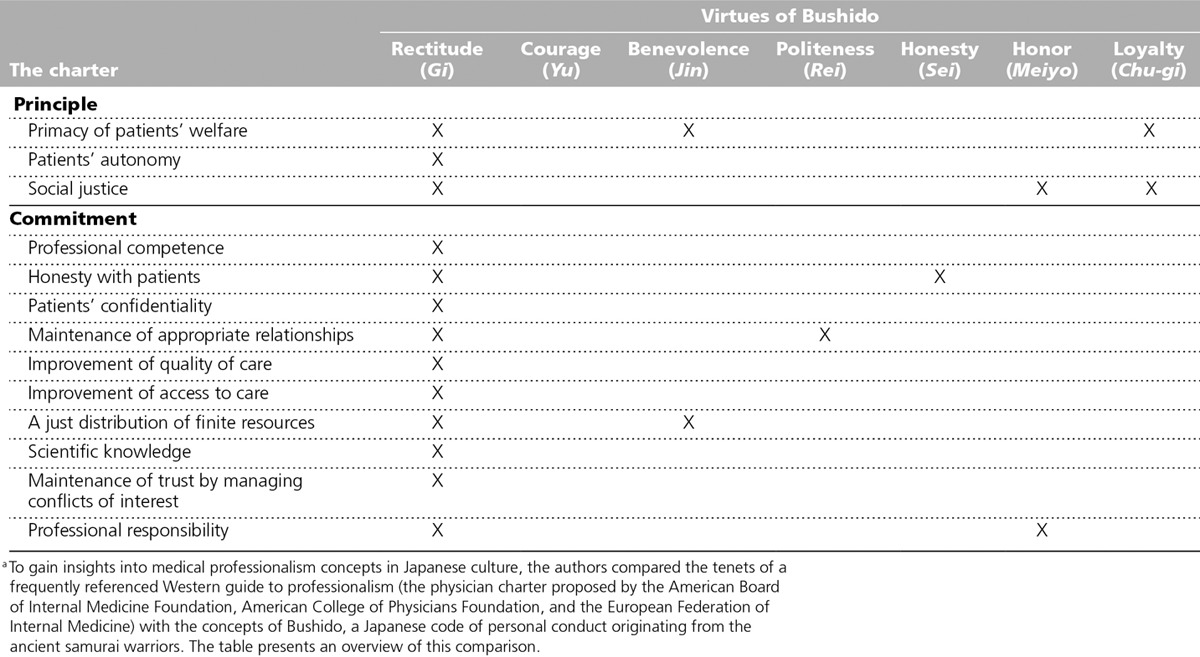

There are also several commitments in the physician charter that are not present in Bushido, because the charter describes medical professionalism, whereas Bushido describes a code of conduct for people in general. This difference can be seen in Table 1, which presents a comparison of the 7 virtues of Bushido and the 3 principles and 10 commitments of the physician charter.

Table 1.

Comparison Between the 7 Virtues of Bushido and the 3 Principles and 10 Commitments Written in the Physician Chartera

Concepts in Bushido That Differ From Contemporary Views of Professionalism

Examples of differences

Although Bushido is intrinsically intertwined with the values of Japanese society,2 it has concepts that differ from—and sometimes conflict with—contemporary notions of professionalism. Bushido does not address the autonomy of the individual, which is one of the principles in the physician charter. This omission may encourage paternalistic relationships between doctors and patients in Japan; such relationships are increasingly considered unacceptable in Western culture. In the chapter on self-control, which is an associated virtue in Bushido, Nitobe11 stated that the Japanese were required not to show their emotions to others, expressed in the phrase “He shows no sign of joy or anger.” Although this behavior might be considered an appropriate trait in Japan, it can cause miscommunication between doctors and patients. Inequality between men and women is another example, rooted in Bushido, where the roles of women were classified as naijo, the “inner help” of the home. With the recent influx of women into Japanese medicine, such challenges as maintaining work–life balance (e.g., through flexible work arrangements) are transforming the traditional concept of Japanese work ethics and provoking intergenerational discussions that are shaping the present-day view.18

Factors behind the differences

Many factors account for differences between Bushido and the physician charter. An important factor is religion. For example, although the social contract between medicine and society is very important in discussing medical professionalism,6 the concept of a “social contract” is foreign to Japanese culture (and probably other non-Judeo-Christian cultures), as it implies a covenant based on Judeo-Christian principles. Another example: In Confucian cultures like Japan, young people are expected to show respect for elderly people. Demonstrating politeness (rei) to an older person calls for a type of deference on the part of a doctor that might not be seen in Western cultures.

The extent to which a culture values individualism is another factor influencing the professionalism of doctors.19 Loyalty (chu-gi) motivates doctors to give greater weight to the interests of the group in cultures like Japan’s that value a collective approach.

A final, and very basic, difference between the physician charter and Bushido is that the former is founded in an ethical system based on duty and rules, whereas Bushido is founded in virtue ethics,20 which concerns the character of the actor. In ethical systems based on duties and rules, one judges whether a course of action is ethical or not according to its adherence to ethical principles, focusing on doing, whereas virtue ethicists judge whether an action is ethical according to the character trait the actor embodies, focusing on being. Virtue ethics has attracted increased interest in the field of general philosophy in recent years and has also entered into discussions about medical professionalism,21 such as this one.

A Call for Multicultural Perspectives on Professionalism

While recognizing that Bushido was in full force at a particular time and place in Japanese history and culture and is by no means a comprehensive ethical system, we suggest that its concepts are applicable to discussions of medical professionalism for those teaching and practicing in Japan today, and merit further study. Given the pace of globalization, which can easily cause the hegemonic imposition of Western culture and discourage cultural diversity, we hope this article will encourage a richer discussion, from the viewpoints of different cultures, on the meaning of professionalism in today’s health care practice.

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank Dr. Yoshiyasu Terashima for taking part in a symposium, “Bushido and Medical Professionalism in Japan,” with Hiroshi Nishigori at the 39th annual meeting of the Japan Society for Medical Education. The authors also wish to thank Dr. Gordon Noel, Dr. Graham McMahon, Mr. Christopher Holmes, and Prof. Kimitaka Kaga for reviewing the manuscript.

We sent our survey to 422 practicing physicians registered in a doctors’ directory in Japan. We asked them to rate, on a five-point scale, the extent to which the seven virtues of Bushido are still alive in their daily clinical practices and to add comments explaining their responses.

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Previous presentations: Earlier versions of this essay were presented at the 39th annual meeting of the Japan Society for Medical Education, Iwate, Japan, July 27, 2007, and in a preconference workshop, Association of Medical Education in Europe 2007, Trondheim, Norway, September 25, 2007.

References

- 1.Stern DT, Papadakis M. The developing physician—becoming a professional. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1794–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Mook WNKA, de Grave WS, Wass V, et al. Professionalism: Evolution of the concept. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:e81–e84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medical Professionalism Project. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physicians’ charter. Lancet. 2002;359:520–522. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07684-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blank L, Kimball H, McDonald W, Merino J ABIM Foundation; ACP Foundation; European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter 15 months later. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:839–841. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-10-200305200-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Physician Charter on Medical Professionalism—ABIM Foundation. http://www.abimfoundation.org/Professionalism/Physician-Charter.aspx. Accessed December 18, 2013.

- 6.Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Linking the teaching of professionalism to the social contract: A call for cultural humility. Med Teach. 2010;32:357–359. doi: 10.3109/01421591003692722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho MJ, Lin CW, Chiu YT, Lingard L, Ginsburg S. A cross-cultural study of students’ approaches to professional dilemmas: Sticks or ripples. Med Educ. 2012;46:245–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyazaki J, Bito S, Obu S. Inside a Pocket of a White Coat: Considering Medical Professionalism in Japan [in Japanese] Tokyo, Japan: Igaku shoin; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. 10th ed. Vol. 930. Springfield, Mass: Merriam-Webster, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plotnikoff GA, Amano T. A culturally appropriate, student-centered curriculum on medical professionalism. Minn Med. 2007;90 http://www.minnesotamedicine.com/PastIssues/PastIssues2007/August2007/ClinicalPlotnikoffAugust2007.aspx. Accessed December 18, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nitobe I. Bushido: The Soul of Japan. New York, NY: Kodansha USA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine DN. The liberal arts and the martial arts. Liberal Educ. 1984;70(3) http://aiki-extensions.org/pubs/liberal_martial_arts.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonda N. Bushido (chivalry) and the traditional Japanese moral education. Online J Bahá’í Stud. 2007 http://oj.bahaistudies.net/OJBS_1_Sonda_Bushido.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haitao L. A cultural interpretation of Japan’s Bushido. Dongjiang J. 2008 http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-DJXK200801008.htm. Accessed December 18, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hori M. Medical professionalism in Bushido [in Japanese]. Sogo Rinsho. 2008;57:1497–1498. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coulter ID, Wilkes M, Der-Martirosian C. Altruism revisited: A comparison of medical, law and business students’ altruistic attitudes. Med Educ. 2007;41:341–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2007.02716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell JC, Ikegami N. The Art of Balance in Health Policy: Maintaining Japan’s Low-Cost, Egalitarian System. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nomura K, Yano E, Fukui T. Gender differences in clinical confidence: A nationwide survey of resident physicians in Japan. Acad Med. 2010;85:647–653. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2a796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Triandis HC. Individualism and Collectivism (New Directions in Social Psychology) Boulder, Colo: Westview Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Definition of virtue ethics. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-virtue/. Accessed December 8, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bryan CS, Babelay AM. Building character: A model for reflective practice. Acad Med. 2009;84:1283–1288. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b6a79c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]