Abstract

Background and purpose

Stenting has been used as a rescue therapy in patients with intracranial arterial stenosis and a TIA or stroke while on antithrombotic therapy (AT). We determined whether the SAMMPRIS trial supported this approach by comparing the treatments within subgroups of patients whose qualifying event (QE) occurred on versus off of AT.

Methods

The primary outcome, 30-day stroke and death and later strokes in the territory of the qualifying artery, was compared between (1) percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting plus aggressive medical therapy (PTAS) versus aggressive medical therapy alone (AMM) for patients whose QE occurred on versus off AT and between (2) patients whose QE occurred on versus off AT separately for the treatment groups.

Results

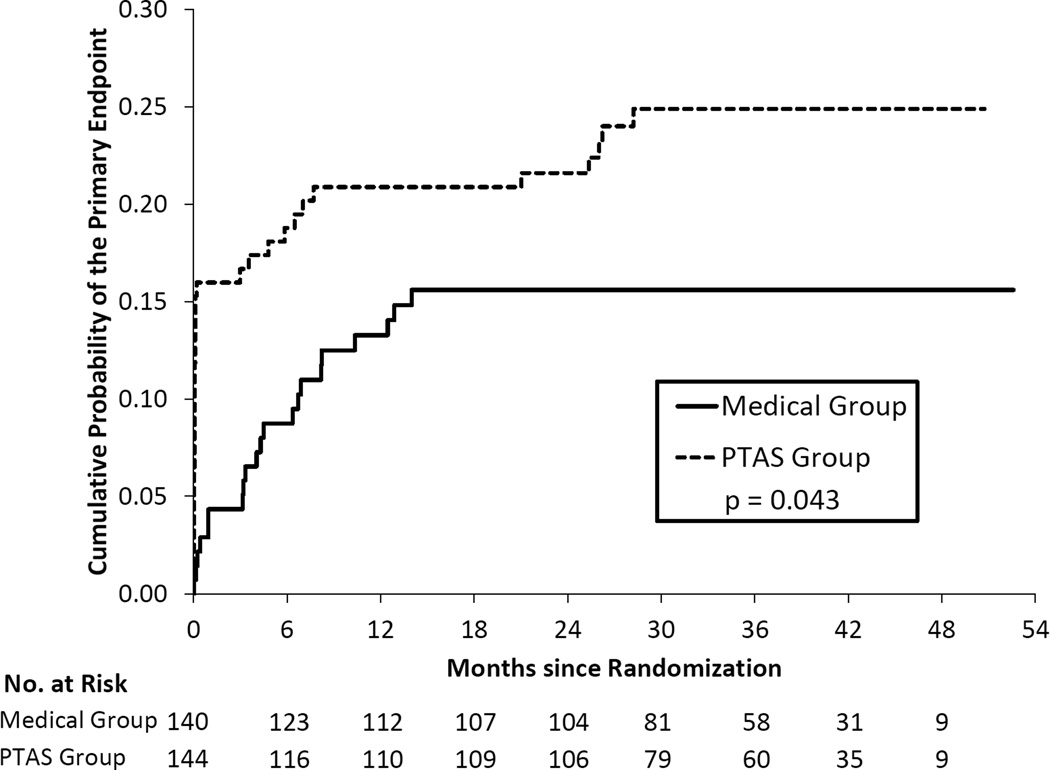

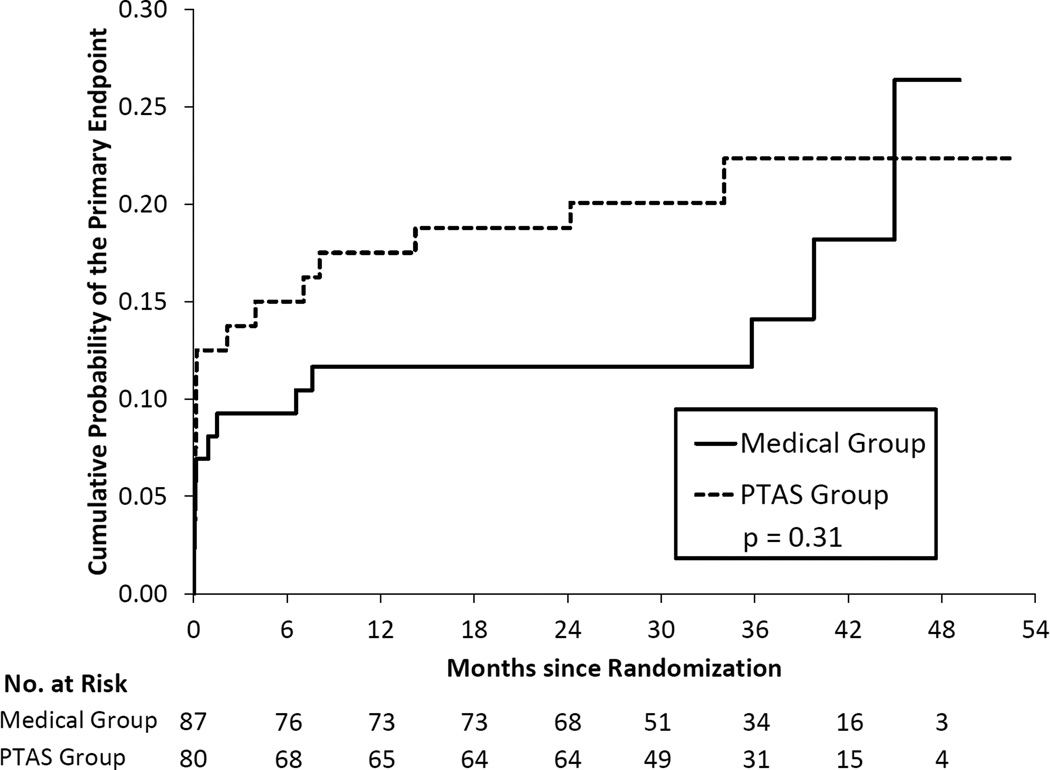

Among the 284/451 (63%) patients who had their QE on AT, the 2-year primary endpoint rates were 15.6% for those randomized to AMM (n=140) and 21.6% for PTAS (n=144) (p=0.043, logrank test). In the 167 patients not on AT, the 2-year primary endpoint rates were 11.6% for AMM (n=87) and 18.8% for PTAS (n=80) (p=0.31, logrank test). Within both treatment groups there was no difference in the time to the primary endpoint between patients who were on or off AT (AMM: p=0.96, PTAS: p=0.52, logrank test).

Conclusions

SAMMPRIS results indicate that the benefit of AMM over PTAS is similar in patients on versus off AT at the QE and that failure of AT is not a predictor of increased risk of a primary endpoint.

Keywords: Intracranial stenosis, antiplatelet agents, angioplasty and stenting, ischemic stroke

Prior to the publication of the results of the Stenting versus Aggressive Medical Therapy for Intracranial Arterial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) trial, the Wingspan stent was being used in clinical practice as a rescue treatment to prevent recurrent stroke in patients with 50–99% intracranial arterial stenosis (ICAS) who had a TIA or stroke while on antithrombotic therapy. The rationale for this approach was uncertain since the preceding Warfarin Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) trial had shown similar rates of recurrent stroke on medical treatment alone in patients whose qualifying event for that trial occurred on vs. off antithrombotic therapy (1).

SAMMPRIS showed that patients with a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke within 30 days prior to enrollment that was attributed to a high grade, 70–99%, stenosis of a major intracranial artery had greater benefit from Aggressive Medical Management alone (AMM) than with Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty and Stenting with the Wingspan stent plus Aggressive Medical Management (PTAS) (2,3). SAMMPRIS did not require patients to be refractory to antithrombotic therapy to be enrolled in the trial, which provided us with the opportunity to determine if stenting is a rescue therapy for patients with a TIA or stroke while on antithrombotic therapy (so called antithrombotic failures), and to compare the outcomes between patients whose qualifying event for SAMMPRIS occurred on versus off antithrombotic therapy. We report the results of these pre-specified analyses in this paper.

Methods

The study design for the SAMMPRIS trial has been published previously (4). AMM included antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel 75 mg per day for 90 days and aspirin 325 mg per day indefinitely, careful risk factor management that primarily targeted a systolic blood pressure < 140 mmHg (<130 mmHg in diabetics) and an LDL <70 mg/dl, and a lifestyle modification program (4). Stenting was performed using the Wingspan stent system and the patients treated with PTAS also received the same AMM including treatment with the antiplatelet agent regimen, careful risk factor control, and the lifestyle modification program. All patients gave written informed consent to participate and institutional review boards at all 50 participating sites in the USA approved the study protocol.

The patients in the current study represent all of those enrolled in SAMMPRIS, divided into those who had their qualifying event on antithrombotic therapy and those that did not. Patients were included in the antithrombotic therapy group whether they were on single or multiple antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants at the time of the qualifying event and irrespective of the duration of treatment. The primary endpoint consisted of stroke and death within 30 days after enrollment or within 30 days after a revascularization procedure during follow-up, and ischemic stroke in the territory of the qualifying artery beyond 30 days after enrollment.

Baseline characteristics were compared between patients taking and not taking an antithrombotic at the time of the qualifying events using Fisher’s exact test (for percentages), independent groups t test (for means) or Wilcoxon rank sum test (for medians). The same methods were used to compare baseline characteristics between treatment groups. Time to event curves for the primary endpoint were compared between treatment groups using the logrank test separately for patients taking and not taking an antithrombotic at the time of the qualifying event. Analyses comparing treatment groups adjusting for baseline characteristics that were different between the treatment groups and that were related to the primary endpoint were done using proportional hazards regression. The same methods were used to assess the association between the use of an antithrombotic at the time of the qualifying event and time to a primary endpoint separately for each of the treatment groups.

Results

Baseline Characteristics in Patients On vs. Off Antithrombotic Therapy at Qualifying Event

A total of 451 patients were enrolled in SAMMPRIS and randomized to either AMM (n=227) or PTAS (n=224). The majority, 284/451 (63%), of patients had their qualifying event on antithrombotic therapy while 167/451 (37%) were not on antithrombotic therapy. Of the patients on antithrombotic therapy, the majority were on one or more antiplatelet agents at the time of the qualifying event (272/284, 95.8%) with 64 (22.5%) on both clopidogrel and aspirin. Far fewer patients were on an anticoagulant (12/284, 4.2%). Of the patients on antiplatelet therapy, 182/272 (66.9%) were on a single antiplatelet agent at the time of their qualifying event with the vast majority on aspirin alone (153/182, 84.1%). Other antiplatelet agents used in various combinations included clopidogrel, aspirin/dipyridamole, prasugrel (one patient) and cilostazol (one on single therapy and two in combination with aspirin or clopidogrel).

A number of characteristics differed at baseline between the groups with a qualifying event on versus off antithrombotic therapy (Table 1). Patients with their qualifying event on antithrombotic therapy were significantly older and had a significantly higher frequency of lipid disorders, coronary artery disease, stroke prior to the qualifying event, presence of old infarct on baseline brain imaging, and vertebral or basilar stenosis. Patients off antithrombotic therapy had a significantly higher frequency of stroke as the qualifying event for SAMMPRIS and middle cerebral artery stenosis.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics by whether or not the patient was taking an antithrombotic medication at the time of the qualifying event

| Characteristic | Taking Antithrombotic (n=284) |

Not Taking Antithrombotic (n=167) |

p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 61.3 ± 11.0 | 58.4 ± 11.6 | 0.008 |

| Male Gender | 177 (62%) | 95 (57%) | 0.27 |

| Race | 0.49 | ||

| Black | 62 (22%) | 42 (25%) | |

| White | 208 (73%) | 114 (68%) | |

| Other | 14 (5%) | 11 (7%) | |

| Hypertension | 260 (92%) | 143 (86%) | 0.058 |

| Diabetes | 137 (48%) | 71 (43%) | 0.24 |

| Lipid Disorder | 263 (93%) | 134 (80%) | < 0.0001 |

| History of Coronary Artery Disease | 92 (32%) | 14 (8%) | < 0.0001 |

| History of Stroke (Not Qualifying Event) | 100 (35%) | 18 (11%) | < 0.0001 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 146 ± 21 (n=282) | 145 ± 22 (n=165) | 0.69 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 153 ± 44 (n=280) | 158 ± 43 (n=166) | 0.22 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 95 ± 38 (n=280) | 100 ± 37 (n=166) | 0.13 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 38 ± 10 (n=280) | 39 ± 11 (n=166) | 0.45 |

| Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) | 31 ± 6 | 30 ± 6 | 0.37 |

| Smoking | 0.22 | ||

| Never | 108 (38%) | 60/166 (36%) | |

| Previously | 106 (37%) | 53/166 (32%) | |

| Currently | 70 (25%) | 53/166 (32%) | |

| Physical Activity in Target† | 96/283 (34%) | 46/166 (28%) | 0.21 |

| Presence of Old Infarcts | 110/276 (40%) | 34/161 (21%) | < 0.0001 |

| Qualifying Event was Stroke | 165 (58%) | 129 (77%) | < 0.0001 |

| Time from Qualifying Event to Randomization (Days) | 8 (4, 18) | 7 (4, 18) | 0.58 |

| Symptomatic Artery | 0.005 | ||

| Internal Carotid Artery (ICA) | 59 (21%) | 35 (21%) | |

| Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA) | 108 (38%) | 89 (53%) | |

| Vertebral Artery | 45 (16%) | 15 (9%) | |

| Basilar Artery | 72 (25%) | 28 (17%) | |

| Percent Stenosis of Symptomatic Artery * | 80 ± 6 | 81 ± 7 (n=166) | 0.48 |

| Categories of Percent Stenosis of the Symptomatic Artery * | 0.83 | ||

| 70–79% | 134 (47%) | 75/166 (45%) | |

| 80–89% | 119 (42%) | 70/166 (42%) | |

| 90–99% | 31 (11%) | 21/166 (13%) | |

Values are mean ± standard deviation or number (%) except for Time from Qualifying Event to Randomization for which the values are median (25th percentile, 75th percentile).

p-value comparing groups for Fisher’s exact test (for percentages), independent groups t test (for means) or Wilcoxon rank sum test (for median of Time from Qualifying Event to Randomization)

The target range for physical activity was 30 minutes or more of moderate exercise at least 3 times per week.

According to a reading of the angiogram by the site interventionist

PTAS vs. AMM in Patients On vs. Off Antithrombotic Therapy at Qualifying Event

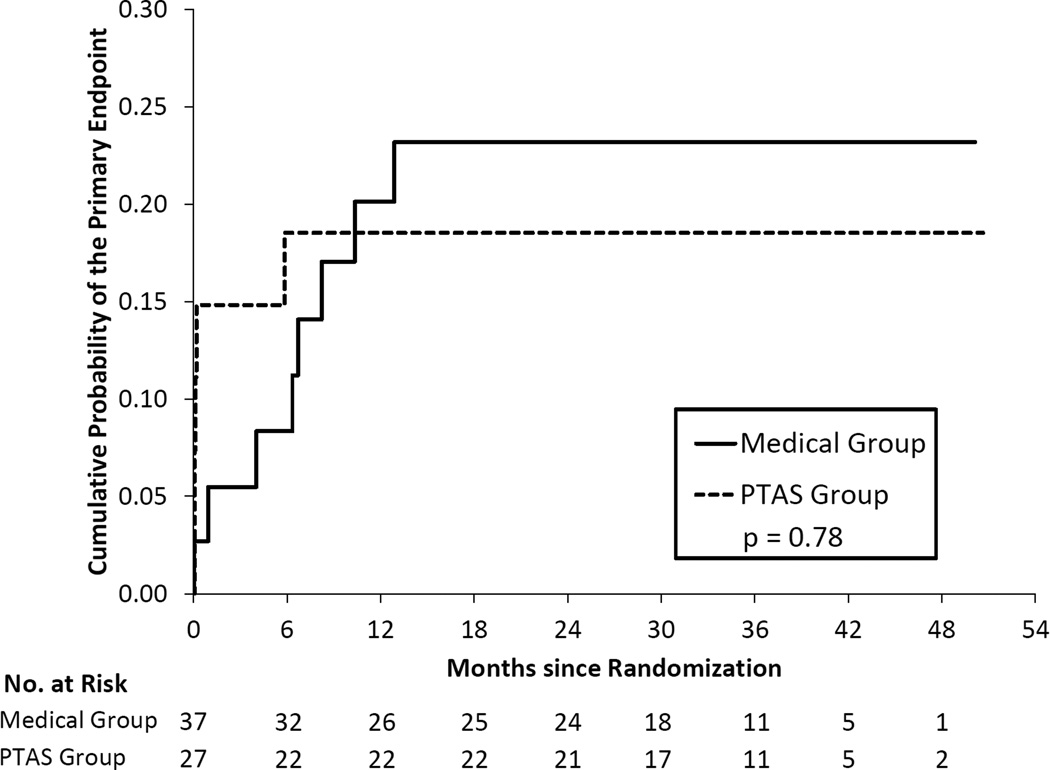

Table 2 provides a comparison of treatment groups, AMM and PTAS, for the primary endpoint within patient groups defined by antithrombotic status at the time of the qualifying event. Of the 284 patients on antithrombotic therapy at the time of the qualifying event, 140 patients were randomized to AMM and 144 to PTAS. The Kaplan Meier curves were significantly different in these two groups (p=0.043) and yielded 2-year rates of the primary endpoint of 15.6% in the AMM group and 21.6% in the PTAS group (Figure 1). Only 64 patients were on clopidogrel plus aspirin at the time of their qualifying event, with 37 of these patients randomized to AMM and 27 to PTAS. The 2-year rates of the primary endpoint were 18.5% (95% CI = 8.2% – 38.9%) in the PTAS group and 23.2% (95% CI = 12.3% – 41.1%) in the AMM group and the Kaplan Meier curves were not significantly different (p=0.78). (Figure 2). Of the 167 patients not on antithrombotic therapy at the time of the qualifying event, 87 patients were randomized to AMM and 80 to PTAS. The 2-year rates of the primary endpoint were 11.6% in the AMM group and 18.8% in the PTAS group but the Kaplan Meier curves were not significantly different (p=0.31), (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Results for the primary endpoint according to treatment and the use of antithrombotic use at the time of the qualifying event

| Antithrombotic Status | Medical Group | PTAS Group | p- value* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Patients | # Patients with Event (%) |

Probability at 1 Yr (95% CI) |

Probability at 2 Yrs (95% CI) |

# Patients | # Patients with Event (%) |

Probability at 1 Yr (95% CI) |

Probability at 2 Yrs (95% CI) |

||

| On Antithrombotic | 140 | 21 (15%) |

13.3% (8.6% – 20.2%) |

15.6% (10.5% – 22.9%) |

144 | 35 (24%) |

20.9% (15.1% – 28.5%) |

21.6% (15.7% – 29.3%) |

0.043 |

| Not On Antithrombotic | 87 | 13 (15%) |

11.6% (6.4% – 20.6%) |

11.6% (6.4% – 20.6%) |

80 | 17 (21%) |

17.5% (10.8% – 27.8%) |

18.8% (11.8% – 29.2%) |

0.31 |

| p- value† |

0.96 | 0.52 | |||||||

p-value for the logrank test comparing the time to event curves of the two treatment groups separately for patients who were and were not taking an antithrombotic medication at the time of the qualifying event.

p-value for the logrank test comparing the time-to-event curves of patients who were and were not taking an antithrombotic medication at the time of the qualifying event separately for each of the treatment groups.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for the primary endpoint in the two treatment groups for patients taking an antithrombotic at the time of the qualifying event.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for the primary endpoint in the two treatment groups for patients taking aspirin and clopidogrel at the time of the qualifying event.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for the primary endpoint in the two treatment groups for patients not taking an antithrombotic at the time of the qualifying event.

The baseline characteristics listed in Table 1 were compared between the treatments separately for patients on antithrombotic therapy, patients on aspirin and clopidogrel, and patients off antithrombotic therapy at the time of the qualifying event. The only statistically significant differences between treatments were the following: (1) For patients taking aspirin and clopidogrel at the time of the qualifying event, a higher percentage of patients in the AMM group had a history of coronary artery disease (57% vs 26%, p = 0.021); (2) For patients not on antithrombotic therapy at the time of the qualifying event, the patients in the AMM group were younger on average (56.3 ± 11.9 years vs 60.7 ± 10.9 years, p = 0.014). Among patients not on an antithrombotic at the time of the qualifying event, an analysis adjusting for age using proportional hazards regression found that similarly to the unadjusted analysis, treatment was not significantly related to the primary endpoint (p = 0.59).

Outcome in Patients On vs. Off Antithrombotic Therapy at Qualifying Event

For patients randomized to AMM, antithrombotic use at the time of the qualifying event was not significantly related to the primary endpoint (p = 0.96, Table 2). Antithrombotic use was also not statistically significant (p = 0.51) when adjusting for baseline factors found to be related to the primary endpoint among AMM patients (stroke as the qualifying event and the presence of old infarcts in the territory of the stenotic artery) (5). Twenty of 21 (95%) ischemic strokes in the AMM group on antithrombotics were in the territory of the stenotic vessel. In the AMM group not on antithrombotics, 11 of 12 (92%) occurred in the territory of the stenotic vessel.

A similar result was found for patients randomized to PTAS. Antithrombotic use at the time of the qualifying event was not significantly related to the primary endpoint (p = 0.52, Table 2) and was also not statistically significant (p = 0.77) when adjusting for baseline factors found to be related to the primary endpoint among PTAS patients (age, diabetes, and qualifying stenosis in the basilar artery) (6). All of the ischemic strokes in the PTAS treatment population occurred in the territory of the stenotic vessel (28/28 in the antithrombotic group and 13/13 in the PTAS group not on antithrombotics).

Discussion

The results of this pre-specified analysis of the SAMMPRIS data set do not support the practice of using PTAS with the Wingspan stent system as a rescue treatment in ICAS patients who have a TIA or stroke on antithrombotic therapy. In fact the SAMMPRIS data indicate that patients whose qualifying event occurred on antithrombotic therapy, which was in most cases antiplatelet treatment with aspirin, had a significantly lower rate of the primary endpoint in the AMM group compared with the PTAS group. Patients that had been on antithrombotic therapy at the time of the qualifying event had a significantly higher frequency of important risk factors than patients who had not been on antithrombotic therapy. The presence of these risk factors likely resulted in more medical care and the use of antithrombotic therapy in these patients prior to enrollment in SAMMPRIS. It is possible that certain of the risk factors contributed to the risk of intervention with PTAS (6). The fact that these patients had more benefit from AMM than PTAS provides compelling support for the use of aggressive medical management in these patients.

In patients who had their qualifying event on a combination of clopidogrel and aspirin, the primary outcome was slightly lower in the PTAS group than in the AMM group but this was not statistically significant (p=0.78). The lack of randomization in patients who had their qualifying event on dual antiplatelet therapy coupled with the small number of patients in this subgroup limits any definitive conclusions regarding the comparative efficacy of PTAS versus AMM for this subgroup. Further studies are needed to determine if patients with ICAS who have a stroke on dual antiplatelet therapy are at higher risk of recurrent stroke and, if so, whether this risk can be mitigated by intensive management of vascular risk factors or other treatments such as ischemic conditioning (7) or another endovascular approach such as angioplasty (8). Of note, following the SAMMPRIS trial, the FDA changed the Humanitarian Device Exemption outlining the use of the Wingspan stent to stipulate that the device could only be used in patients with 70–99% stenosis who have had two or more strokes despite aggressive medical management which includes strict blood pressure and LDL control not just the use of antiplatelet therapy (9).

The findings in the current study that patients on an antithrombotic agent at the time of the qualifying event are at no greater risk of a primary endpoint than patients not on an antithrombotic agent support those of the earlier Warfarin Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) trial that compared warfarin to aspirin in patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis. A post-hoc analysis of the WASID trial found no difference in outcomes, either a combined endpoint of stroke or vascular death or stroke in the territory of the stenotic vessel, in patients that were on an antithrombotic at the time of their qualifying event versus those that were not on an antithrombotic (1). While recurrent stroke rates were lower in SAMMPRIS than in WASID, the rates in patients both on and off of antithrombotic therapy are still undesirably high and better therapies are needed.

This study has some important limitations. Although the analyses were pre-specified, the study was not powered specifically to compare outcomes in patients on vs. off antithrombotic therapy at the time of the qualifying event. In particular, there was very limited power to investigate outcomes in patients on various antithrombotic therapies including those on dual antiplatelet treatment. Additionally, other features of the patients such as use of statins and blood pressure control at the time of the qualifying event, which may have impacted subsequent risk of a primary endpoint, were not collected.

The current study has shown that antithrombotic failure is not a predictor of increased risk of a primary endpoint in either treatment arm. In the group that failed antithrombotic therapy, PTAS did not serve as a rescue therapy. Aggressive medical management is the treatment of choice in patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis and management should not be influenced by whether or not the patient was already on antithrombotic therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

The Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) trial is funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant number: U01 NS058728). The authors received support as listed below.

Michael J. Lynn, MS has received salary support from the SAMMPRIS grant. He receives grant support from the National Eye Institute. He is the principal investigator of the Coordinating Center for Infant Aphakia Treatment Study (EY013287) and a co-investigator on the Core Grant for Vision Research (EY006360).

Tanya N. Turan, MD has received salary support from the SAMMPRIS grant and served on the Executive Committee and as Director of Risk Factor Management. She is the current recipient of an NIH-funded grant. She serves on Clinical Events Committees for trials funded by Gore & Associates, Boehringer Ingelheim and the NIH.

Colin Derdeyn MD has received salary support from the SAMMPRIS grant. Dr. Derdeyn serves on the angio core lab for a trial (Microvention) and on two Data and Safety Monitoring Boards (Silk Road and Penumbra).

David Fiorella MD, PhD has received salary support from the SAMMPRIS grant. He has received institutional research support from Seimens Medical Imaging and Microvention, consulting fees from Codman/Johnson and Johnson, NFocus, W.L. Gore and Associates, and EV3/Covidien, and royalties from Codman/Johnson and Johnson. He has received honoraria from Scientia and has ownership interest in CVSL and Vascular Simulations.

L. Scott Janis PhD is a program director at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Marc Chimowitz, MBChB is the grant recipient (U01 NS058728) for the NINDS funded SAMMPRIS trial discussed in this paper. He has received salary support from the SAMMPRIS grant. Stryker Neurovascular donated stents for the SAMMPRIS trial and paid for some third party monitoring in the trial. AstraZenica donated the statin medication for the SAMMPRIS trial. Dr. Chimowitz has served as an expert witness in medical legal cases.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Helmi L. Lutsep, MD: None

Stanley L. Barnwell, MD, PhD: None

Darren T. Larsen, RN: None

Mindy Hong, MSPH: None

Contributor Information

Helmi L Lutsep, Oregon Health & Science Univ, Portland, OR.

Stanley L Barnwell, Oregon Health & Science Univ, Portland, OR.

Darren T Larsen, Oregon Health & Science Univ, Portland, OR.

Michael J Lynn, Emory Univ Rollins Sch of Public Health, Atlanta, GA.

Mindy Hong, Emory Univ Rollins Sch of Public Health, Atlanta, GA.

Tanya N Turan, Medical Univ of South Carolina, Charleston, SC.

Colin P Derdeyn, Washington Univ Sch of Med, St. Louis, MO.

David Fiorella, State Univ of New York, Stony Brook, NY.

L. Scott Janis, Natl Insts of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Marc I Chimowitz, ChB Medical Univ of South Carolina, Charleston, SC.

References

- 1.Turan TN, Maidan L, Cotsonis G, Lynn MJ, Romano JG, Levine SR, et al. Failure of antithrombotic therapy and risk of stroke in patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis. Stroke. 2009;40:505–509. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.528281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, Turan TN, Fiorella D, Lane BF, et al. the SAMMPRIS Trial Investigators. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:993–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derdeyn CP, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Fiorella D, Turan TN, Janis LS, et al. Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis Trial Investigators. Lancet. 2014;383:333–341. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turan TN, Lynn MJ, Nizam A, Lane B, Egan BM, Le NA, et al. Rationale, design, and implementation of aggressive risk factor management in the Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Prevention of Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:e51–e60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waters MF, Hoh BL, Lynn MJ, Turan TN, Derdeyn CP, Fiorella D, et al. Risk factors associated with failure of aggressive medical therapy in the SAMMPRIS trial. Stroke. 2014;45:A78. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiorella D, Derdeyn CP, Lynn MJ, Barnwell SL, Hoh BL, Levy EI, et al. Detailed analysis of periprocedural strokes in patients undergoing intracranial stenting in Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) Stroke. 2012;43:2682–2688. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.661173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meng R, Asmaro K, Meng L, Liu Y, Ma C, Xi C, et al. Upper limb ischemic preconditioning prevents recurrent stroke in intracranial arterial stenosis. Neurology. 2012;79:1853–1861. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318271f76a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McTaggart RA, Marks MP. The case for angioplasty in patients with symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis. Front Neurol. 2014;5:e36. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narrowed indications for use for the Stryker Wingspan Stent System: FDA safety communication. [Accessed September 26, 2014];U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm314600.htm.