Abstract

Background

As the number of cervical spine procedures performed continues to increase, the need for revision surgery is also likely to increase. Surgeons need to understand the etiology of post-surgical changes, as well as have a treatment algorithm when evaluating these complex patients.

Questions/Purposes

This study aims to review the rates and etiology of revision cervical spine surgery as well as describe our treatment algorithm.

Methods

We used a narrative and literature review. We performed a MEDLINE (PubMed) search for “cervical” and “spine” and “revision” which returned 353 articles from 1993 through January 22, 2014. Abstracts were analyzed for relevance and 32 articles were reviewed.

Results

The rates of revision surgery on the cervical spine vary by the type and extent of procedure performed. Patient evaluation should include a detailed history and review of the indication for the index procedure, as well as lab work to rule out infection. Imaging studies including flexion/extension radiographs and computed tomography are obtained to evaluate potential pseudarthrosis. Magnetic resonance imaging is helpful to evaluate the disc, neural elements, soft tissue, and to differentiate scar from infection. Sagittal alignment should be corrected if necessary.

Conclusions

Recurrent or new symptoms after cervical spine reconstruction can be effectively treated with revision surgery after identifying the etiology, and completing the appropriate workup.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11420-014-9394-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: cervical, revision, pseudarthrosis, adjacent segment

Introduction

Revision rates for surgery on the cervical spine can be high, and vary by the type of procedure performed. For anterior cervical decompression and fusion (ACDF), the 2-year revision rate ranges from 2.1% to 9.13% for single level surgery, and from 4.4% to 10.7% for multilevel ACDF [44, 53]. For these procedures, the most common reason for revision surgery is adjacent segment disease, which has an average incidence of new symptoms between 1.6% to 4.2% per year [19, 26]. Reoperation rates in patients undergoing cervical disc arthroplasty is reported to range from 1.8% to 5.4% at 2 years [3, 32] to 2.9% at 5-year follow-up [51, 59]. For posterior procedures, the revision rate after cervical foraminotomy has been reported to range from 2.9% at 7 years [11] to 5% at 31.7 months [54] compared to laminoplasty with a revision rate ranging from 2.1% at 15 years [42] to 13% at 42.3 months, and laminectomy and fusion which has a revision rate ranging from 2% [55] to 27% at 41.3 months [18]. These high revision rates emphasize the need for surgeons to have a thorough understanding of the etiology of post-surgical pathology, as well as a treatment algorithm when evaluating a patient who has undergone prior cervical spine surgery.

The purpose of this article is to review MEDLINE literature after 1993 in order to (1) identify and review the important aspects in the diagnosis and evaluation of patients after failed cervical spine reconstruction and (2) to describe a treatment algorithm when addressing failed cervical spine reconstruction.

Methods

We performed a MEDLINE (PubMed) search for “cervical” and “spine” and “revision” which returned 353 articles from 1993 through January 22, 2014. Abstracts were analyzed for relevance and 32 articles were included.

Results

Of the articles reviewed, there was variation in the rates of revision surgery based on procedure type, as well as revision strategy. The focus of the articles in regards to diagnosis and evaluation of patients undergoing revision surgery for failed cervical spine reconstruction included: history and physical exam, imaging, sagittal alignment, laboratory testing, and recurrent laryngeal nerve evaluation. The surgical approaches and treatment algorithm depend on the etiology for revision, which were most commonly: infection, adjacent segment disease, recurrent symptoms, kyphosis, and pseudarthrosis.

Evaluation (History and Physical Exam)

A detailed history and physical exam is crucial when evaluating a patient for possible revision cervical spine surgery. Regardless of whether or not the initial procedure was completed by another surgeon or yourself, the same treatment approach should be used, including a reassessment of the indications for the initial procedure. In addition to understanding the patient’s current symptoms, the surgeon must understand why the initial surgery was done, and if any relief was obtained after the index procedure. A review of clinical notes from the initial surgeon may also be helpful in elucidating specific physical exam findings as well as the impression and treatment plan prior to the primary surgery. Operative reports, including the type of instrumentation used, as well as details of the postoperative course such as length of hospital stay, clinical impression, or lab work which raises concern for infection, dysphagia, hoarseness, and any other complications are also important for future surgical planning. Current signs or symptoms of myelopathy, progressive weakness, weight loss, fever, chills, nausea, or vomiting may be indicative of a condition requiring an urgent intervention. Medical comorbidities and smoking and alcohol history should be evaluated and optimized before any non-urgent procedure, including nutritional evaluation if necessary.

To complement the routine physical exam done for all cervical spine evaluations, attention to the previous incision is important to identify wound healing deficiencies and to suggest the presence of infection through drainage or erythema, fluctuance, pain on palpation, or underlying masses. Signs of poor nutrition should elicit further workup for metabolic disorders such as vitamin deficiencies. The side, orientation, and size of the initial incision, along with any vocal cord dysfunction will guide planning for revision procedures. If upper extremity symptoms are present, the shoulder, elbow, and wrist should be thoroughly evaluated, and peripheral compressive neuropathies should be excluded.

Imaging

Initial imaging for revision cervical spine surgery includes standing anteroposterior, lateral, and flexion/extension radiographs. Full-length radiographs may be important when addressing cervical deformity which impacts overall coronal and sagittal balance. Radiographs will allow measurement of local kyphosis/lordosis based on Cobb angle, as well as an assessment of motion through an attempted fusion site, and overall range of motion on the flexion/extension films. Plain radiographs will show implant failure such as screw or rod breakage, as well as lucencies around screws indicative of pseudarthrosis. Computed tomography (CT) provides fine bony detail and further assessment of fusion status.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides information about disc integrity, neural elements, bony structures, as well as the surrounding soft tissue structures. Determining the difference between scar tissue, disc tissue, and fluid collections, which may raise concern for infection, can be difficult, and MRI with and without gadolinium can help differentiate. Scar tissue will enhance on T1-weighted images after the administration of gadolinium and disc material and fluid collections will not.

Sagittal Alignment

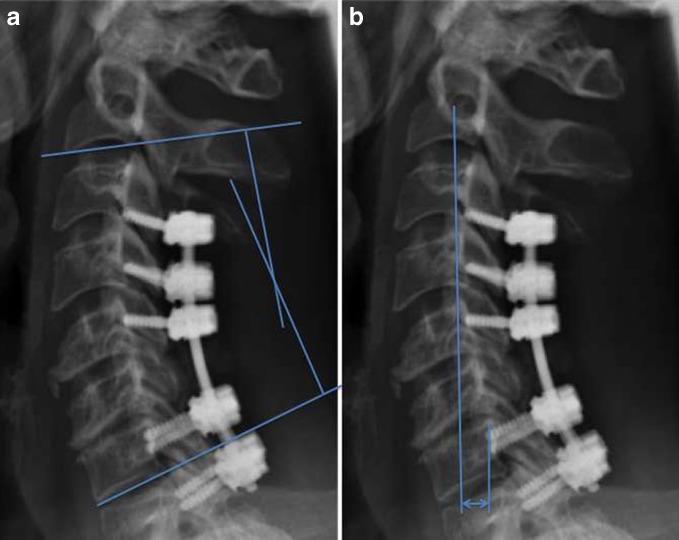

Sagittal alignment of the cervical spine is an important parameter that can effect quality of life [39], and full-length standing radiographs should be obtained if this is a potential concern. There are multiple methods to measure cervical spine alignment, and the Cobb angle of C2-C7 ranges from 9.6° [16] to 14.4° of lordosis in the normal patient [58] (see Fig. 1a). Almost 2/3 of load transmission occurs through the posterior columns [35]. Kyphotic malalignment of the cervical spine can occur after surgery, especially if a laminectomy is performed in patients with pre-existing kyphosis [21, 30, 43]. The cervical sagittal vertical axis (SVA) is a measurement of translation, which can either be measured globally from C2 or C7 to the posterior superior sacrum, or regionally within the cervical spine from C2 to C7 [39] (see Fig. 1b). The chin–brow vertical angle (CBVA) is a measure of horizontal gaze, and should also be considered when planning the correction of a kyphotic deformity, particularly in patients with ankylosing spondylitis [48].

Fig. 1.

a C2-C7 Cobb angle is measured as the intersection of lines perpendicular to the inferior endplate of C2 and the inferior endplate of C7. b C2-C7 sagittal vertical axis (SVA) is measured as the distance from a plumb line from the center of C2 to the posterior superior aspect of the C7 body.

Laboratory Testing

Concerns for infection at any time point after surgery should prompt evaluation with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and complete white blood cell count (WBC) with differential. In the normal postoperative period, CRP and ESR will peak on the third and fourth day, respectively, then CRP will decrease rapidly, and ESR will gradually decrease [24]. Both can still be elevated at 14 days after surgery, and ESR can remain elevated for up to 6 weeks [24]. A second rise in CRP, or a failure of CRP to decrease is concerning for infection [31] When treating an infection after surgery, the CRP level is more indicative of response to antibiotic treatment, as ESR may continue to be elevated [23]. Procalcitonin levels have also been studied as potential markers for infection [10, 34]; however, the exact relationship to infected spine wounds is not clear at this time.

In patients with a history of dysphagia, nutritional markers such as albumin and total lymphocyte count may reveal malnutrition that should be corrected prior to revision surgery if possible. In a database review of patients undergoing spine fusion, patients with an albumin level of 3.5 g/dL or less have higher mortality rate than those with levels higher than 3.5 g/dL (OR 13.8, 95% CI, 4.6–41.6; p < 0.001) [40]. Vitamin D deficiency is also common, and has been reported in up to 27% of adults undergoing spinal fusion [47].

Additional Testing

For revision surgery after anterior cervical approaches, the recurrent laryngeal nerve should be assessed, as the incidence of symptoms after primary surgery is 2.7%, and increases dramatically to 9.5% to 10.5% after revision anterior cervical surgery [4, 12]. Asymptomatic recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy detected by laryngoscopy is even more common, with rates up to 15.9% after primary anterior cervical spine surgery [20]. If there is a history of dysphonia, patients should be evaluated by an otolaryngologist to determine if there is a recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, and subsequent partial or complete vocal cord paralysis. If the vocal cords are normal, the revision procedure may be done from either side. If there is vocal cord paralysis, the approach should be done on the ipsilateral side to avoid injury to the normal side [36]. Any prolonged history of dysphagia also warrants a preoperative otolaryngology consult to evaluate the integrity of the esophagus. Prominent or loose anterior instrumentation in the setting of dysphagia raises the concern of an unrecognized esophageal injury, and intraoperative otolaryngology help may be needed for evaluation of the esophagus. In one series, the rate of acute esophageal perforation during ACDF was low (0.3%) [14], but can be fatal. Late presentation can present years after surgery as dysphagia with the presence of an abscess [9], or be asymptomatic with migrated hardware [38].

Surgical Planning

After completing the appropriate workup, the most common etiologies of pain or disability after cervical spine surgery should be apparent. These include adjacent segment disease, pseudarthrosis, same segment disease, progressive deformity, infection, or a combination of these diagnoses. Although radiographic evidence of adjacent segment degeneration is common after prior cervical spine surgery, the cause of symptoms may be multifactorial, and should not be immediately attributed to adjacent segment disease.

Infection

Infection should always be in the differential diagnosis when evaluating patients with prior cervical spine surgery. As discussed earlier, the laboratory and MRI workup can aid in diagnosis. Early infection can present as a draining wound or fluid collection, and should be treated with urgent irrigation and debridement, with attempted hardware retention if possible. Intraoperative cultures should be taken to help guide antibiotic treatment. Repeat debridements may be necessary depending on the severity and virulence of the pathogen, and condition of the soft tissues. A vacuum-assisted closure dressing may help temporarily, and drains should be used as necessary.

Late infection may present with increasing pain and/or neurologic symptoms. Instrumentation loosening should also raise concern for infection. Loose instrumentation should be removed and, depending on the stability and condition of the spine, new instrumentation may be necessary for stabilization. The overall alignment of the spine, assessment of fusion, and presence of adjacent segment disease should also be evaluated and addressed as needed. Intravenous antibiotics will likely be necessary for 6–8 weeks in the case of infection with antibiotic choice based on the intraoperative cultures.

Adjacent Segment Disease

Adjacent segment disease (ASD) is common after cervical spine surgery. After anterior cervical arthrodesis, the rate is approximately 2.9% per year [19], and after a second cervical fusion, the incidence of ASD is up to 25%[56]. A recent systematic review found the average incidence of adjacent segment degeneration, which is a radiographic finding and may be asymptomatic, to be 47.33% and ASD to be 11.99% (average follow-up of 106.5 months, range 50.4 to 253.2 months) [7]. The high incidence of ASD is likely multifactorial, due to natural history and biomechanical effects. While the biomechanical effects of an anterior fusion procedure increased intradiscal pressure and motion at adjacent levels [13], this alone likely does not entirely explain ASD. Patients undergoing posterior laminoforaminotomy develop both same-level degeneration and ASD, suggesting more than just biomechanics contributes to this condition [11, 17, 54]. In patients undergoing ACDF, disc degeneration on preoperative MRI was found to be more common at levels adjacent to the operative level compared to non-adjacent levels, also suggesting that the natural history contributes to ASD [29].

Surgical techniques can also contribute to adjacent segment degeneration. Placing a plate within 5 mm of the adjacent level has been associated with ossification of that level [37]. Similarly, placing a localizing needle at the incorrect adjacent level leads to a threefold increase in adjacent segment degeneration [33]. Along with unnecessary soft tissue dissection, these technical mistakes are potentially avoidable etiologies for the development of ASD and should be avoided as much as possible.

Revision surgery for adjacent segment disease should also evaluate the fusion status of the original interbody space if the index procedure was an ACDF or the posterolateral fusion mass if the procedure was a posterior fusion. Anterior plates will likely need to be revised to include the adjacent segment, and any neural compression should be addressed.

Recurrent Symptoms

For patients with recurrent symptoms after a period of relief, or patients who never experienced relief after the initial procedure, the same segment should be evaluated for recurrent stenosis or incomplete decompression of stenosis. Peripheral compressive neuropathy should also be ruled out, as these can mimic recurrent disease. CT and MRI are used to localize compressive lesions. Sagittal alignment should be assessed, which can be affected by collapsed or subsided grafts or cages.

In addition to symptoms being caused by recurrent or incompletely relieved stenosis, other more rare causes of neurologic deficit should be considered, especially when imaging studies do not explain the clinical presentation. The differential diagnosis may include diabetic neuropathy, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, vitamin B12 deficiency, syringomyelia, and intracranial pathology [1]. Irreversible spinal cord and nerve root damage should be considered, and patients should be counseled about the possibility of not fully recovering function, regardless of the treatment offered. High-intensity spinal cord signal with a well-defined border on T2-weighted MR images, along with low signal intensity change on T1-weighted images, are indicative of a poor surgical outcome [8, 49].

Once the underlying diagnosis is made, surgical planning should define the overall goals of the revision surgery and the approach. An anterior approach should be used to address compression from anterior structures, including the PLL and uncovertebral joints. Multilevel compression with neutral or kyphotic alignment necessitates either multiple ACDFs or an anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF). Kyphosis may be better corrected with multiple ACDFs; however, if there is an associated pseudarthrosis, there is a higher risk of needing a second-revision surgery with anterior procedures compared to posterior procedures [6]. Posterior instrumentation should be considered with more than three-level anterior fusions. Multilevel corpectomy can also correct a kyphotic deformity to neutral, and should also be stabilized posteriorly if more than two levels are involved, due to a high risk of graft dislodgement [52]. Patients with neutral or lordotic alignment can have laminectomy and fusion to address multiple segments if instability is a concern, or laminoplasty and/or foraminotomies if no significant neck pain or instability is present.

Kyphosis

Kyphosis is common after laminectomy without fusion, occurring in up to 21% of cases [22]. Pre-existing kyphosis, facetectomies, and older age increases the likelihood of kyphosis [2]. The loss of sagittal alignment shifts the weight-bearing axis anteriorly, which can cause muscular fatigue and pain as well as spinal cord draping and neural compromise. The goals of surgery are to lengthen the anterior column and to shorten or relatively shorten the posterior column in order to correct the overall sagittal alignment. Flexion and extension radiographs can help determine if the deformity is rigid or fixed, which will affect surgical planning. CT scan will evaluate the location and integrity of fusion masses and ankylosed bone, which may necessitate a corrective osteotomy. If a patient can correct to neutral on extension radiographs, either an anterior or posterior only approach may be used. Posterior arthrodesis can be performed if there are no anterior compressive structures, and laminoforaminotomies should be added as needed to prevent root compression as the neck is extended. Anterior-only multilevel ACDF is preferred for flexible deformity with anterior compression, because of the ability to increase lordosis up to 20° [46]. For fixed deformities, a combined anterior/posterior approach, with or without osteotomies may be necessary in order to restore sagittal balance and decompress the spinal cord.

Pseudarthrosis

The rate of pseudarthrosis increases with multiple fusion levels, and pain is the most common presenting symptom [5]. In multilevel anterior cervical fusion, the pseudarthrosis most commonly occurs at the lowest fusion level, and even with BMP-2 augmentation, the rate is approximately 10% [41]. After laminectomy and fusion, the pseudarthrosis rate was found to range from 1% to 38% in a recent systematic review [57]. Flexion and extension radiographs and CT scan can evaluate the fusion site (Fig. 2). Using a cutoff value of more than 4° of intervertebral body motion on flexion/extension radiographs has been demonstrated to have a high positive predictive value for diagnosing pseudarthrosis [15]. Determining anterior cervical fusion on CT scan can be difficult, and a recent study found that extra-graft-bone bridging is much more accurate and reliable to determine fusion than intra-graft-bone bridging [45]. As stated earlier, evaluation of potential contributing factors for pseudarthrosis, such as infection, medical comorbidities, malnutrition, and smoking status should be undertaken and corrected if possible before revision surgery. If patients are asymptomatic, treatment of pseudarthrosis may be nonoperative.

Fig. 2.

Flexion (a) and extension (b) radiographs of a 47-year-old female smoker who underwent C4-C7 ACDF and developed a painful pseudarthrosis at C4-C5. Postoperative flexion (c) and extension (d) radiographs after revision procedure of posterior C4-C5 decompression and C4-C7 fusion.

For patients with neck pain, neurologic symptoms, or instability, operative treatment is indicated. In patients with anterior cervical pseudarthrosis, either an anterior revision procedure [50], or a posterior fusion procedure can lead to good results [25, 27]. A combined anterior/posterior procedure may be necessary to achieve stability in some cases. The fusion rates for posterior revision surgery is reported to be much higher (94%–98%) compared to anterior revision (44%–45%); however, complication rates are lower anteriorly [6, 28]. In patients with a prior posterior decompression, an anterior revision procedure is preferred if possible to avoid the exposed dura posteriorly. Regardless of approach used, all fibrous nonunion tissue should be removed, bone graft or bone graft substitute should be added as necessary, and rigid fixation should be obtained.

Discussion

With the ongoing development of surgical techniques and devices for the cervical spine, there will be a need for revision surgery. It is important for clinicians to understand the evaluation and diagnosis of patients after failed cervical spine reconstruction, as well as to have a consistent treatment algorithm when addressing failed cervical spine reconstruction. The literature reports wide ranges of rates for revision cervical spine surgery, likely due to the inherent differences in procedures, as well as variability of indications for revision surgery between clinicians. Randomized controlled trials to determine the optimal approach for revision surgery would be beneficial, however, these studies are difficult to complete.

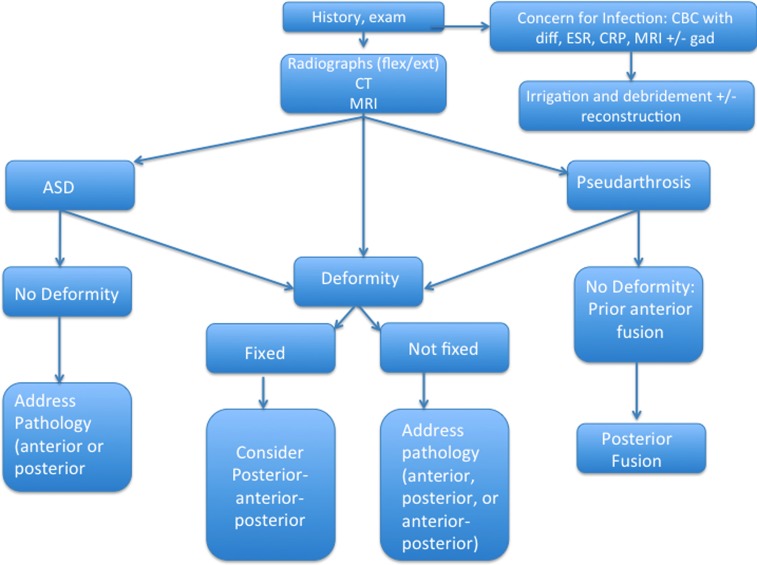

Our treatment algorithm for revision cervical spine reconstruction includes a thorough history and physical exam and review of the initial indication for surgery, and inquiry as to whether or not a pain-free interval was ever obtained after surgery (Fig. 3). If concerns for pseudarthrosis exist at 6 months from surgery, flexion/extension radiographs are obtained, and possibly, a CT scan. If radiculopathy or neural compression is evident from history or physical exam, an MRI is obtained. If there is concern for infection, ESR, CRP, and CBC with differential are ordered, as well as an MRI with gadolinium.

Fig. 3.

Flow chart describing our treatment algorithm for cervical spine revision surgery (see Discussion for narrative) flex/ext-flexion/extension; CT computed tomography, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, CBC with diff-complete blood count with differential, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP c-reactive protein, ASD adjacent segment disease.

Our approach to revision cervical spine surgery depends on the etiology. In cases of postoperative kyphosis, our operative strategy is to lengthen the anterior column and shorten the posterior column, which is usually performed with anterior–posterior procedures. Occasionally, for cases with a fixed deformity, posterior–anterior–posterior approaches are used to explore and perform osteotomies, if necessary, followed by anterior release and decompression, and then instrumentation posteriorly. In cases of ASD without deformity, the approach is dependent on the location of the neural compression. In pseudarthrosis cases after prior ACDF without deformity, we prefer attempting a posterior fusion. For anterior revision procedures, we evaluate the vocal cords, and if normal, we prefer to approach the spine from the contralateral side to avoid the scarring.

Revision cervical spine surgery is common, with rates varying depending on the initial procedure performed. Clinicians should have an understanding of the most common causes for revision surgery, as well as have an approach for the evaluation and treatment of these complex cases.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 1,224 kb)

(PDF 1,224 kb)

(PDF 1,225 kb)

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest:

John D. Koerner, MD, and Christopher K. Kepler, MD, MBA, have declared that they have no conflict of interest. Todd J. Albert, MD, receives royalties from Depuy and Biomet Spine; receives consultant fees from Depuy and Facetlink; stock option or stocks from K2M, Vertech, In Vivo Therapeutics, Paradigm Spine, Pearldriver, Biomerix, Breakaway Imaging, Crosstree, Invuity, Pioneer, Gentis, ASIP, PMIG, and Spinicity, outside the work.

Human/Animal Rights:

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed Consent:

N/A

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Footnotes

This work was performed at the Rothman Institute, Thomas Jefferson University and Hospital, Philadelphia, PA

References

- 1.Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. In: Ropper AS, MA, ed.: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 2009.

- 2.Albert TJ, Vacarro A. Postlaminectomy kyphosis. Spine. 1998;23:2738–2745. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199812150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson PA, Sasso RC, Riew KD. Comparison of adverse events between the Bryan artificial cervical disc and anterior cervical arthrodesis. Spine. 2008;33:1305–1312. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817329a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beutler WJ, Sweeney CA, Connolly PJ. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury with anterior cervical spine surgery risk with laterality of surgical approach. Spine. 2001;26:1337–1342. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200106150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohlman HH, Emery SE, Goodfellow DB, et al. Robinson anterior cervical discectomy and arthrodesis for cervical radiculopathy. Long-term follow-up of one hundred and twenty-two patients. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 1993;75:1298–1307. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carreon L, Glassman SD, Campbell MJ. Treatment of anterior cervical pseudoarthrosis: posterior fusion versus anterior revision. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2006;6:154–156. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrier CS, Bono CM, Lebl DR. Evidence-based analysis of adjacent segment degeneration and disease after ACDF: a systematic review. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Chen CJ, Lyu RK, Lee ST, et al. Intramedullary high signal intensity on T2-weighted MR images in cervical spondylotic myelopathy: prediction of prognosis with type of intensity. Radiology. 2001;221:789–794. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2213010365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christiano LD, Goldstein IM. Late prevertebral abscess after anterior cervical fusion. Spine. 2011;36:E798–802. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181fc9b09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung YG, Won YS, Kwon YJ, et al. Comparison of serum CRP and procalcitonin in patients after spine surgery. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 2011;49:43–48. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2011.49.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke MJ, Ecker RD, Krauss WE, et al. Same-segment and adjacent-segment disease following posterior cervical foraminotomy. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2007;6:5–9. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coric D, Branch CL, Jr, Jenkins JD. Revision of anterior cervical pseudoarthrosis with anterior allograft fusion and plating. Journal of neurosurgery. 1997;86:969–974. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.6.0969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eck JC, Humphreys SC, Lim TH, et al. Biomechanical study on the effect of cervical spine fusion on adjacent-level intradiscal pressure and segmental motion. Spine. 2002;27:2431–2434. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fountas KN, Kapsalaki EZ, Nikolakakos LG, et al. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion associated complications. Spine. 2007;32:2310–2317. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318154c57e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghiselli G, Wharton N, Hipp JA, et al. Prospective analysis of imaging prediction of pseudarthrosis after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: computed tomography versus flexion-extension motion analysis with intraoperative correlation. Spine. 2011;36:463–468. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d7a81a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardacker JW, Shuford RF, Capicotto PN, et al. Radiographic standing cervical segmental alignment in adult volunteers without neck symptoms. Spine. 1997;22:1472–1480. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199707010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herkowitz HN, Kurz LT, Overholt DP. Surgical management of cervical soft disc herniation. A comparison between the anterior and posterior approach. Spine. 1990;15:1026–1030. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199015100-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Highsmith JM, Dhall SS, Haid RW, Jr, et al. Treatment of cervical stenotic myelopathy: a cost and outcome comparison of laminoplasty versus laminectomy and lateral mass fusion. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2011;14:619–625. doi: 10.3171/2011.1.SPINE10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilibrand AS, Carlson GD, Palumbo MA, et al. Radiculopathy and myelopathy at segments adjacent to the site of a previous anterior cervical arthrodesis. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1999;81:519–528. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199904000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung A, Schramm J, Lehnerdt K, et al. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy during anterior cervical spine surgery: a prospective study. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2005;2:123–127. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.2.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamioka Y, Yamamoto H, Tani T, et al. Postoperative instability of cervical OPLL and cervical radiculomyelopathy. Spine. 1989;14:1177–1183. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198911000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaptain GJ, Simmons NE, Replogle RE, et al. Incidence and outcome of kyphotic deformity following laminectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Journal of neurosurgery. 2000;93:199–204. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.3.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan MH, Smith PN, Rao N, et al. Serum C-reactive protein levels correlate with clinical response in patients treated with antibiotics for wound infections after spinal surgery. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2006;6:311–315. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong CG, Kim YY, Park JB. Postoperative changes of early-phase inflammatory indices after uncomplicated anterior cervical discectomy and fusion using allograft and demineralised bone matrix. International orthopaedics. 2012;36:2293–2297. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1645-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhns CA, Geck MJ, Wang JC, et al. An outcomes analysis of the treatment of cervical pseudarthrosis with posterior fusion. Spine. 2005;30:2424–2429. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000184314.26543.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawrence BD, Hilibrand AS, Brodt ED, et al. Predicting the risk of adjacent segment pathology in the cervical spine: a systematic review. Spine. 2012;37:S52–64. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31826d60fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, Ploumis A, Schwender JD, et al. Posterior cervical lateral mass screw fixation and fusion to treat pseudarthrosis of anterior cervical fusion. Journal of spinal disorders & techniques. 2012;25:138–141. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31821532a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowery GL, Swank ML, McDonough RF. Surgical revision for failed anterior cervical fusions. Articular pillar plating or anterior revision? Spine. 1995;20:2436–2441. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199511001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundine KM, Davis G, Rogers M, Staples M, Quan G. Prevalence of adjacent segment disc degeneration in patients undergoing anterior cervical discectomy and fusion based on pre-operative MRI findings. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Mikawa Y, Shikata J, Yamamuro T. Spinal deformity and instability after multilevel cervical laminectomy. Spine. 1987;12:6–11. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198701000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mok JM, Pekmezci M, Piper SL, et al. Use of C-reactive protein after spinal surgery: comparison with erythrocyte sedimentation rate as predictor of early postoperative infectious complications. Spine. 2008;33:415–421. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318163f9ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murrey D, Janssen M, Delamarter R, et al. Results of the prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemption study of the ProDisc-C total disc replacement versus anterior discectomy and fusion for the treatment of 1-level symptomatic cervical disc disease. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2009;9:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nassr A, Lee JY, Bashir RS, et al. Does incorrect level needle localization during anterior cervical discectomy and fusion lead to accelerated disc degeneration? Spine. 2009;34:189–192. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181913872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nie H, Jiang D, Ou Y, et al. Procalcitonin as an early predictor of postoperative infectious complications in patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injury. Spinal cord. 2011;49:715–720. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pal GP, Sherk HH. The vertical stability of the cervical spine. Spine. 1988;13:447–449. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198805000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paniello RC, Martin-Bredahl KJ, Henkener LJ, et al. Preoperative laryngeal nerve screening for revision anterior cervical spine procedures. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2008;117:594–597. doi: 10.1177/000348940811700808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park JB, Cho YS, Riew KD. Development of adjacent-level ossification in patients with an anterior cervical plate. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2005;87:558–563. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.01555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pompili A, Canitano S, Caroli F, et al. Asymptomatic esophageal perforation caused by late screw migration after anterior cervical plating: report of a case and review of relevant literature. Spine. 2002;27:E499–502. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheer JK, Tang JA, Smith JS, et al. International Spine Study G. Cervical spine alignment, sagittal deformity, and clinical implications: a review. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2013;19:141–159. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.SPINE12838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schoenfeld AJ, Carey PA, Cleveland AW, 3rd, et al. Patient factors, comorbidities, and surgical characteristics that increase mortality and complication risk after spinal arthrodesis: a prognostic study based on 5,887 patients. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2013;13:1171–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen HX, Buchowski JM, Yeom JS, et al. Pseudarthrosis in multilevel anterior cervical fusion with rhBMP-2 and allograft: analysis of one hundred twenty-seven cases with minimum two-year follow-up. Spine. 2010;35:747–753. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f46352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shigematsu H, Koizumi M, Matsumori H, Iwata E, Kura T, Okuda A, Ueda U, Tanaka Y. Revision surgery after cervical laminoplasty: report of five cases and literature review. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Sim FH, Svien HJ, Bickel WH, et al. Swan-neck deformity following extensive cervical laminectomy. A review of twenty-one cases. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1974;56:564–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh K, Phillips FM, Park DK, et al. Factors affecting reoperations after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion within and outside of a Federal Drug Administration investigational device exemption cervical disc replacement trial. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2012;12:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song KS, Chaiwat P, Kim HJ, Mesfin A, Park SM, Riew KD. Anterior cervical fusion assessment using reconstructed CT-scans: surgical confirmation of 254 segments. Spine. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Steinmetz MP, Kager CD, Benzel EC. Ventral correction of postsurgical cervical kyphosis. Journal of neurosurgery. 2003;98:1–7. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.1.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stoker GE, Buchowski JM, Bridwell KH, et al. Preoperative vitamin D status of adults undergoing surgical spinal fusion. Spine. 2013;38:507–515. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182739ad1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suk KS, Kim KT, Lee SH, et al. Significance of chin-brow vertical angle in correction of kyphotic deformity of ankylosing spondylitis patients. Spine. 2003;28:2001–2005. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000083239.06023.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tetreault LA, Dettori JR, Wilson JR, et al. Systematic review of magnetic resonance imaging characteristics that affect treatment decision making and predict clinical outcome in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 2013;38:S89–S110. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a7eae0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tribus CB, Corteen DP, Zdeblick TA. The efficacy of anterior cervical plating in the management of symptomatic pseudoarthrosis of the cervical spine. Spine. 1999;24:860–864. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199905010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaccaro A, Beutler W, Peppelman W, et al. Clinical outcomes with selectively constrained SECURE-C cervical disc arthroplasty: two-year results from a prospective, randomized, controlled, multicenter investigational device exemption study. Spine. 2013;38:2227–2239. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vaccaro AR, Falatyn SP, Scuderi GJ, et al. Early failure of long segment anterior cervical plate fixation. Journal of spinal disorders. 1998;11:410–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Veeravagu A, Cole T, Jiang B, Ratliff JK. Revision rates and complication incidence in single- and multilevel anterior cervical discectomy and fusion procedures: an administrative database study. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Wang TY, Lubelski D, Abdullah KG, Steinmetz MP, Benzel EC, Mroz TE. Rates of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion after initial posterior cervical foraminotomy. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Woods BI, Hohl J, Lee J, et al. Laminoplasty versus laminectomy and fusion for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2011;469:688–695. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1653-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu R, Bydon M, Macki M, De la Garza-Ramos R, Sciubba DM, Wolinsky JP, Witham TF, Gokaslan ZL, Bydon A. Adjacent segment disease after ACDF: Clinical outcomes after first repeat surgery versus second repeat surgery. Spine. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Yoon ST, Hashimoto RE, Raich A, et al. Outcomes after laminoplasty compared with laminectomy and fusion in patients with cervical myelopathy: a systematic review. Spine. 2013;38:S183–194. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a7eb7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zdeblick TA, Zou D, Warden KE, et al. Cervical stability after foraminotomy. A biomechanical in vitro analysis. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1992;74:22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zigler JE, Delamarter R, Murrey D, et al. ProDisc-C and anterior cervical discectomy and fusion as surgical treatment for single-level cervical symptomatic degenerative disc disease: five-year results of a Food and Drug Administration study. Spine. 2013;38:203–209. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318278eb38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1,224 kb)

(PDF 1,224 kb)

(PDF 1,225 kb)