Abstract

Objectives:

HIV-1 replication depends on the state of cell activation and division. It is established that SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection of resting CD4+ T cells. The modulation of SAMHD1 expression during T-cell activation and proliferation, however, remains unclear, as well as a role for SAMHD1 during HIV-1 pathogenesis.

Methods:

SAMHD1 expression was assessed in CD4+ T cells after their activation and in-vitro HIV-1 infection. We performed phenotype analyzes using flow cytometry on CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood and lymph nodes from cohorts of HIV-1-infected individuals under antiretroviral treatment or not, and controls.

Results:

We show that SAMHD1 expression decreased during CD4+ T-cell proliferation in association with an increased susceptibility to in-vitro HIV-1 infection. Additionally, circulating memory CD4+ T cells are enriched in cells with low levels of SAMHD1. These SAMHD1low cells are highly differentiated, exhibit a large proportion of Ki67+ cycling cells and are enriched in T-helper 17 cells. Importantly, memory SAMHD1low cells were depleted from peripheral blood of HIV-infected individuals. We also found that follicular helper T cells present in secondary lymphoid organs lacked the expression of SAMHD1, which was accompanied by a higher susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in vitro.

Conclusion:

We demonstrate that SAMHD1 expression is decreased during CD4+ T-cell activation and proliferation. Also, CD4+ T-cell subsets known to be more susceptible to HIV-1 infection, for example, T-helper 17 and follicular helper T cells, display lower levels of SAMHD1. These results pin point a role for SAMHD1 expression in HIV-1 infection and the concomitant depletion of CD4+ T cells.

Keywords: HIV restriction, HIV-1, lymphocyte activation, SAMHD1, T-helper 17 cells

Introduction

The infection of CD4+ T cells by HIV-1 relies on the activation state of the cell [1,2]. It has long been known that activated cells are more prone to HIV-1 infection than quiescent CD4+ T cells [3]. SAMHD1 restricts productive HIV-1 infection in dendritic cells, myeloid cells [4,5] and resting CD4+ T cells [6,7]. Several mechanisms have been proposed for SAMHD1 blocking of HIV-1 infection. Indeed, SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) hydrolase and its expression decreases the intracellular dNTP pool thus blocking the reverse transcription [6–8]. Phosphorylation of SAMHD1, however, has been shown to inhibit the restriction activity of SAMHD1 [9–11], independently of the dNTPase capacity. The ribonuclease activity of SAMHD1 was recently reported to be crucial for HIV-1 restriction [12]. Of importance, several T-cell lines [4–6] as well as peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients suffering T-cell lymphoproliferative disease [13] display low levels of SAMHD1, illustrating the possible modulation of SAMHD1 expression.

Although the mechanisms of SAMHD1 restriction have been the subject of intense investigation, it remains to be determined whether SAMHD1 plays a role in HIV-1 pathogenesis. In the present article, we evaluated the regulation of SAMHD1 expression during CD4+ T-cell activation and found that SAMHD1 levels decrease with cell proliferation. Importantly, the activation-induced SAMHD1 decrease was associated with higher susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in vitro. We found that peripheral memory CD4+ T cells comprise a subset of cells expressing low levels of SAMHD1. Those CD4+SAMHD1low T cells are highly differentiated, enriched in cycling cells and are significantly decreased in HIV-infected individuals as compared with controls. In addition, peripheral T-helper 17 (Th17), as well as lymph nodes follicular helper T (Tfh) cells, two CD4+ T-cell subsets highly susceptible to HIV-1 infection, displayed the lowest expression of SAMHD1. Our results uncover that the regulation of SAMHD1 expression during T-cell activation and differentiation participate to the susceptibility of CD4+ T cells to HIV-1 infection.

Methods

Patient information

Ethical committee approval and written informed consent from all individuals or their parents, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, were obtained prior to study initiation.

Peripheral blood was collected from healthy controls (n = 19) and HIV-1-infected individuals (n = 35) (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1). Among the HIV-1-infected patients, 23 were receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) [median (range) CD4+ T-cell count: 522 (129–1080) cells/μl; HIV-1 RNA: <20 (0–74042) copies/ml], six were either naive to treatment or under treatment interruption [median (range) CD4+ T-cell count: 255 (145–805) cells/μl; HIV-1 RNA: 54047 (982–158169) copies/ml], and six individuals were elite controllers [median (range) CD4+ T-cell count: 900 (737–1483) cells/μl; HIV-1 RNA: 94 (0–308) copies/ml]. Human peripheral blood and cord blood (n = 5) were obtained from Etablissement Français du Sang. PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll gradient centrifugation (PAA Laboratories, Velizy, France) and then either processed immediately or stored frozen until required for analysis.

Tonsils (n = 28) were obtained from children undergoing tonsillectomy at the Necker Hospital, Paris. Mechanical tissue disruption and 70 μm filtration were used to isolate single-cell suspension.

Surgically removed axillary lymph nodes from HIV-1-infected individuals (n = 6, CD4+ T-cell count: 318 (122–573) cells/μl; HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/ml] were obtained from the University Medical Center Eppendorf. HIV-negative lymph node samples (n = 6) were obtained from organ donors, who tested negative for HIV-1 and had no chronic infections, through National Disease Research Interchange, University Medical Center Eppendorf, and Columbia Center for Translational Immunology (Table).

Ex-vivo T-cell phenotype

Multicolor flow cytometry was performed on fresh PBMCs and frozen LNMCs. T-cell subpopulations were determined using the different combinations of the following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies: Pacific Blue, PE-Cy7 or Alexa-Fluor 700anti-CD3, PerCP or Alexa-Fluor 700 anti-CD4, PE anti-CD27, PE-Cy7 anti-CCR7, PE-CF594 anti-CD45RO, Alexa-Fluor 488 anti-CXCR5, Alexa-Fluor 647 anti-CCR4, PE anti-CXCR3, PE-Cy7 anti-CCR6 (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, Pont de Claix (Le), France). Vioblue anti-CD3, APC-Vio770 anti-CD4, APC-Vio770 anti-CD45RO, APC anti-CD28 (Milteniy Biotech, Paris, France). Brillant Violet 421 anti-CD279 (Biolegend, London, UK).

Intracellular staining was carried out using the FoxP3 permeabilization solution kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (eBioscience, Paris, France) together with PE Ki67, PE anti-Bcl-6 (BD Pharmingen) or PE anti-FoxP3 (Biolegend), and Alexa-Fluor 488 anti-SAMHD1 (a gift from O. Schwartz) or rabbit anti-SAMHD1 (Euromedex, Souffelweyersheim, France) followed by Alexa-Fluor 647 antirabbit antibody (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Saint Auben, France).

Dead cells were excluded using the Live/Death Vivid detection kit labeled with an aqua dye (Invitrogen). Fluorescence intensities were measured with an LSR II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using FlowJo version 7.6.5 (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, Oregon, USA).

In vitro T-cell proliferation

Purified CD4+ T-lymphocytes from healthy individuals were separated from PBMCs using the CD4+ T-cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotech) and stained with either 0.25 μmol CFSE or 0.5 μmol Cell Trace Violet (Invitrogen). Purified CD4+ T cells (1 × 106) were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Life Technologies) containing l-glutamine, 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) on a precoated 48-well plate with anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) (Beckman Coulter, Villepinte, France). After 72 h, cells were stained with Vioblue anti-CD3, APC-Vio770 anti-CD4 (Miltenyi Biotech) together with the Aqua Live/Death Vivid detection kit (Invitrogen). Samples were fixed and permeabilized using the FoxP3 permeabilization kit (eBioscience) and further stained with either Alexa Fluor 488 anti-SAMHD1 (a gift from O. Schwartz) or rabbit anti-SAMHD1 (Euromedex) followed by Alexa-Fluor 647 antirabbit antibody (Invitrogen). Fluorescence intensities were measured as described previously. Alternatively, CFSE-labeled cells were sorted according to CFSE fluorescence intensity using a MoFlo Legacy (Beckman Coulter) for mRNA quantification.

In-vitro HIV-1 infection

Purified CD4+ T cells from PBMCs were separated using the CD4+ T-cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotech) and stained with Cell Trace Violet (Invitrogen). CD4+ T cells (1 × 106) were cultured in RPMI-1640 containing l-glutamine, 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) on a precoated 48-well plate with anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) (Beckman Coulter). After 72 h, cells were incubated for 2 h in the presence of 100 ng NL4.3 HIV-1 lab strain virus. We used a wild-type HIV-1, NL4.3 strain, pseudotyped with Vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein (VSV-G) produced in HEK 293T cells as described previously [14]. After washing in RPMI medium, cells were further cultured for 2–3 days on a precoated 48-well plate with anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml). The reverse transcriptase inhibitor nevirapine (used at a final concentration of 25 nmol) was from the NIH AIDS Reagents Program. Cells were stained with aqua Vivid and fixed in PFA 4% in PBS for 15 min before a 20-min incubation in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Quentin Fallavier, France) for permeabilization. Alexa-Fluor 488 anti-SAMHD1 and RD1 KC57 (antip24, Beckman Coulter) were used for intracellular staining as described above.

Alternatively, purified CD4+ T cells from tonsils were separated using the CD4+ T-cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotech) and stained with Cell Trace Violet (Invitrogen). Cells were additionally stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CXCR5 and anti-PD-1, and sorted using a MoFlo Legacy. Sorted CD4+ T cells were infected and then incubated for 2 h in the presence of 100 ng NL4.3 HIV-1 lab strain virus as described above. Cells were then cultured for 3 days in RPMI-1640 containing l-glutamine, 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics (penicillin, streptomycin and gentamicin) for 3 days on 96-well plate previously coated with anti-CD3/CD28 (2 μg/ml each). The final steps were performed as described above.

Statistical analyzes

Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test was used to analyze the difference in SAMHD1 expression in lymphocytes. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni posttests were performed on data of SAMHD1 expression in CD4+ T-cell subpopulations as well as Th cell population repartitions and Ki67 expression between SAMHD1+ and SAMHD1low CD4+ T cells. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunn's multiple comparison tests were used for analyses of SAMHD1 expression during CD4+ T-cell proliferation and the levels of p24 expression after in-vitro infection. Correlations were evaluated using the Spearman's rank correlation test. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses and graphic representation of the results were performed using Prism (v.5.0b; GraphPad, San Diego, California, USA)

Results

TCR triggering induces the decreased expression of SAMHD1 in CD4+ T cells

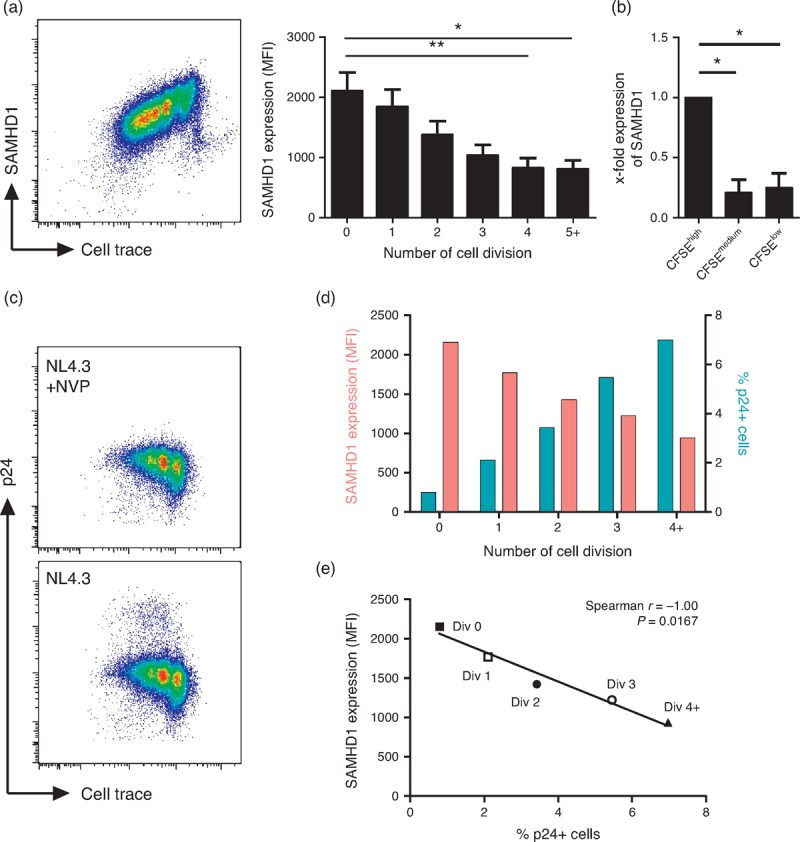

Resting CD4+ T cells express SAMHD1, preventing their infection by HIV-1 [6,7]. The activation of CD4+ T cells is thought not to modify the levels of SAMHD1 expression [6,10]. We used anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies to activate CD4+ T cells and establish whether the expression of SAMHD1 can be modulated during T-cell proliferation. As shown in Fig. 1a, the levels of SAMHD1 gradually decreased with CD4+ T-cell divisions to reach a plateau after four cycles of division. The decrease in protein expression was also associated with decreased SAMHD1-mRNA in proliferating-cells (Fig. 1b). These results are in contrast to previous publication using different activation [6] and/or measuring SAMHD1 expression on the bulk of CD4+ T cells [6,10]. When using phytohemagglutinin and interleukin-2 (PHA/interleukin-2), proliferating CD4+ T cells similarly decreased their expression of SAMHD1 (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 3). We then confirmed that cells expressing lower levels of SAMHD1 were more susceptible to HIV-1 infection in vitro. CD4+ T cells were activated for 72 h with anti-CD3/CD28 then infected for 2 h with the HIV-1 NL4.3-strain. Despite similar levels of phosphorylated SAMHD1 (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 4), proliferating cells showed the highest levels of intracellular p24 (Fig. 1c and d). Notably, there was an inverse correlation between the levels of SAMHD1 and the percentages of p24+ cells (P = 0.016; Fig. 1d and e). Thus, the activation of CD4+ T cells induces a downregulation of SAMHD1 expression in dividing CD4+ T cells that associates with an increased susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in vitro.

Fig. 1.

SAMHD1 expression is decreased during T-cell proliferation and is associated with higher susceptibility to HIV-1 infection.

(a) Purified CD4+ T cells were stained with Cell Trace Violet (n = 14) and cultured in the presence of coated anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) mAbs. At day 5/6, CD3+CD4+ T cells were then stained for SAMHD1. Representative dot-plot of SAMHD1 and Cell Trace staining (left panel) and SAMHD1 expression (right panel) measured by mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) in cells gated according to the number of cell division. Data represent mean with SEM. (b) CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells (n = 3) were sorted according to CFSE dilution after 5 days of culture in the presence of coated anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs. qPCR were then performed for SAMHD1 gene expression on CFSE low, CFSEmedium and CFSEhigh fractions. Data represent fold-change in SAMHD1 gene expression in sorted populations (mean with SEM). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, one-way analysis of variance tests followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test. (c) Purified CD4+ T cells were stained with Cell Trace Violet and cultured in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 (2 μg/ml) for 72 h. Cells were then infected for 2 h with HIV-1 (NL4.3 strain, 100 ng/ml) in the presence or not of nevirapine (NVP), a retrotranscriptase inhibitor. SAMHD1 and p24 (KC57) expression were assessed 48 h postinfection. Dot-plots represent Cell Trace and p24 expression. (d) SAMHD1 expression (red bars) as measured by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and percentages of p24 positive cells (blue bars) among proliferating CD4+ T-cells gated by cell division. (e) Correlation of SAMHD1 MFI and percentages of p24 positive cells on proliferating CD4+ T cells gated by cell division. Data are representative of one experiment out of two.

CD4+ T cells expressing low SAMHD1 are enriched in cycling cells and are depleted during HIV-1 infection

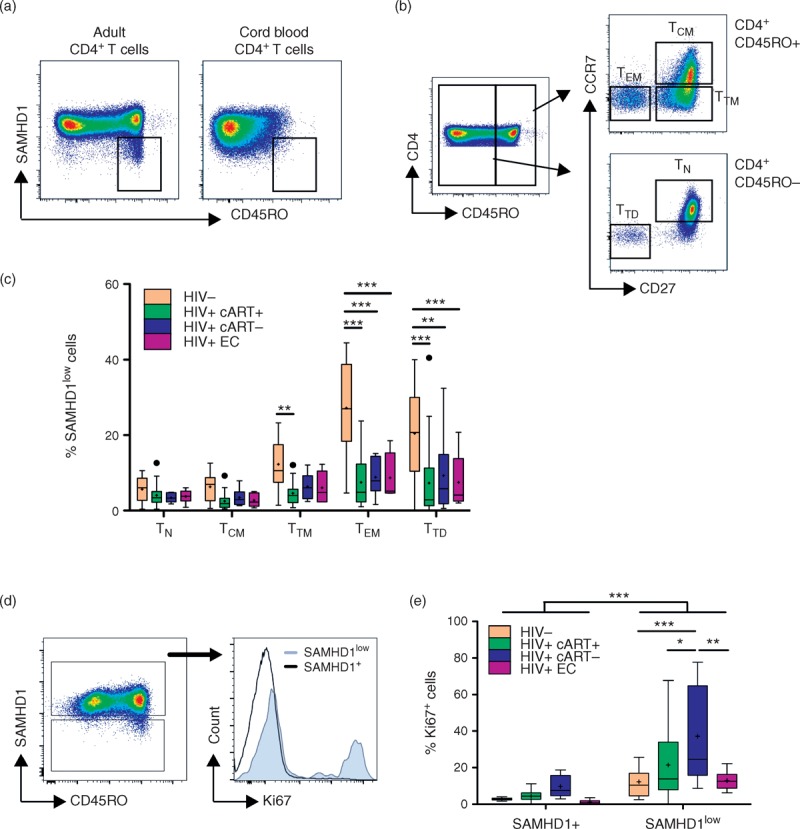

The hallmark of HIV-1 infection is the chronic immune activation [15]. To evaluate whether SAMHD1 expression was also modulated during HIV-1 infection, we assessed its expression in different subsets of CD4+ T cells. As shown previously [6,7], although SAMHD1 was absent in a proportion of lymphocytes (43 ± 19% of non-T cells), it was expressed by most CD3+ T cells (94 ± 0.7%) (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 5). Among CD4+ T cells, we observed that a subset of memory cells displayed low levels of SAMHD1 (Fig. 2a). These SAMHD1low cells were preferentially in the memory compartment of adult PBMCs and could not be identified within cord blood (Fig. 2a). Importantly, ART-treated patients (n = 23), non-ART-treated patients (n = 6) and elite-controllers (n = 6) showed 4.14 ± 2.95, 5.84 ± 3.01 and 5.29 ± 3.3% of SAMHD1low cells in the blood CD4+ T-cell memory compartment, respectively, values significantly lower than those of HIV-negative controls (n = 13, 10.86 ± 5.83%) (data not shown). Deconvolution of the CD4+ T-cell compartment revealed lower proportions of SAMHD1low cells in transitional memory TTM (CCR7−CD27+CD45RO+/RA−), effector memory TEM (CCR7−CD27−CD45RO+/RA−) and terminally differentiated TTD (CCR7−CD27−CD45RO−/RA+) in HIV-positive as compared with HIV-negative individuals (Fig. 2b and c). In contrast, HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals showed similar numbers of SAMHD1low cells within naive (CCR7+CD27+CD45RO−/RA+) and central-memory TCM (CCR7+CD27+CD45RO+/RA−) CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2c). Together these results reveal the presence of a highly differentiated SAMHD1low CD4+ T-cell subset in peripheral blood that is decreased in HIV-infected patients.

Fig. 2.

Low SAMHD1 expression on differentiated and cycling CD4+ T cells ex vivo.

Cord blood (n = 5) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from HIV-1 negative (HIV−, n = 13) or HIV-1-infected individuals treated (HIV+ cART+, n = 23), nontreated (HIV+ cART−, n = 6) or elite controllers (HIV+ EC, n = 6) were stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD45RO or anti-CD45RA, anti-CCR7, anti-CD27, anti-CD28 and anti-SAMHD1. (a) Representative dot-plots of SAMHD1 and CD45RO expression in CD4+ T cells from adult PBMCs and cord blood. (b) Gating strategy of CD4+ T-cell subpopulations into naive (TN: CD45RO−CCR7+CD27+), central memory (TCM: CD45RO+CCR7+CD27+), transitional memory (TTM: CD45RO+CCR7−CD27+), effector memory (TEM: CD45RO+CCR7−CD27+) and terminally differentiated (TTD: CD45RO−CCR7−CD27−). (c) Percentages of SAMHD1low cells among naive (TN), central memory (TCM), transitional memory (TTM), effector memory (TEM), and terminally differentiated (TTD) CD4+ T cells. (d) Representative dot-plots of SAMHD1 and CD45RO expression among live CD4+ T cells showing the gating of SAMHD1+ and SAMHD1low cells (left panel), and representative histogram of Ki67 expression in gated SAMHD1+ and SAMHD1low cells from PBMCs isolated from an nontreated HIV-1 infected individuals. (e) Percentages of Ki67+ cells among SAMHD1+ and SAMHD1low CD4+ T cells from PBMCs isolated from healthy individuals (n = 13) and HIV-1-infected individuals treated (HIV+ cART+, n = 18), nontreated (HIV+ cART−, n = 5) or elites controllers (HIV+ EC, n = 6). Data represent median with 25th–75th interquartile range with means displayed as +. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, two-way analysis of variance tests followed by Bonferroni posttests.

To evaluate whether SAMHD1lowCD4+ T cells are activated in vivo, we measured Ki67 expression, as well as markers of T-cell activation on PBMCs from HIV-negative and HIV-positive individuals. As shown in Fig. 2d and e, SAMHD1lowCD4+ T cells display high levels of Ki67 (P < 0.001 as compared with SAMHD1+CD4+ T cells), thereby indicating their cycling status. SAMHD1lowCD4+ T cells from nontreated HIV-infected individuals exhibited the highest proportion of Ki67+ cells (37.20 ± 27.56%) as compared with ART-treated individuals, elite controllers and healthy controls that showed 21.48 ± 19.71, 12.87 ± 5.49 and 12.23 ± 9.93%, respectively (P < 0.01). Gating strategies for representative patients in each group are shown in Supplemental Digital Content 6. In addition, SAMHD1lowCD4+ T cells showed significantly higher levels of PD-1, CD38 and HLA-DR expression than SAMHD1+CD4+ T cells (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 7), confirming their activated state. Altogether, our data indicate that CD4+ T cells may be losing SAMHD1 expression during their differentiation and proliferation after antigen encounter in vivo.

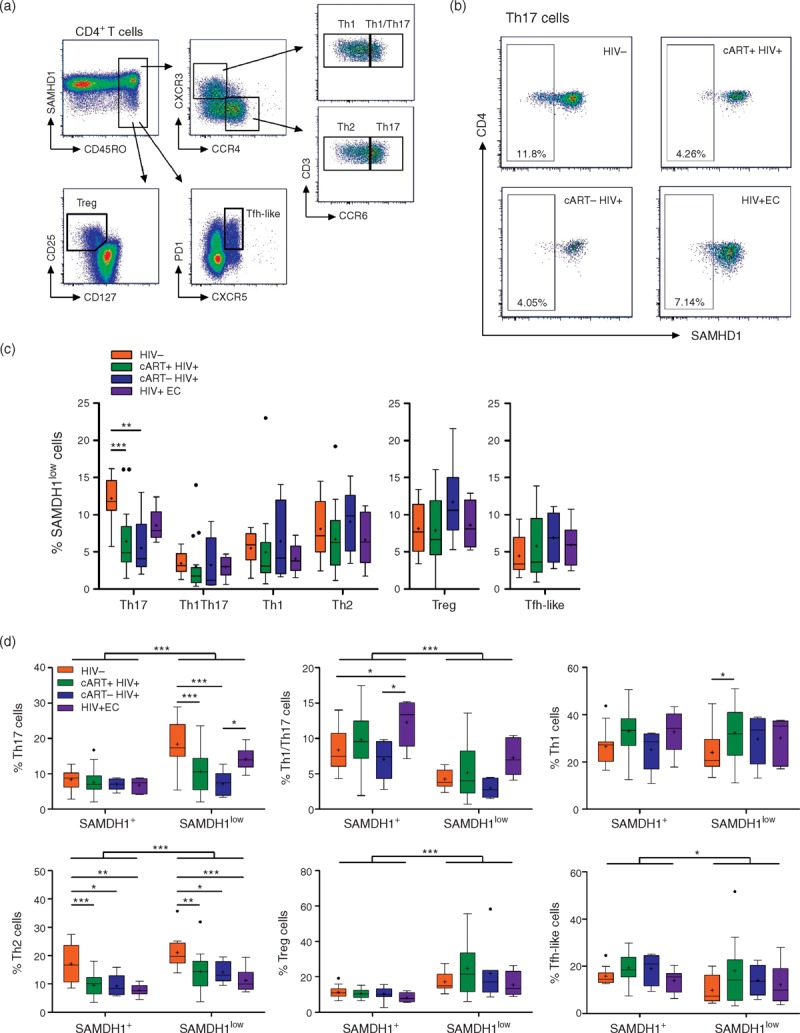

The blood SAMHD1low CD4+ T-cell compartment decrease is restricted to T-helper 17 cells

As differential susceptibility to HIV-1 infection has been described for CD4+ T-cell subsets [16–19], we further examined the expression of SAMHD1 in Th1 (CD45RO+CXCR3+CCR4−CCR6−), Th2 (CD45RO+CXCR3−CCR4+CCR6−), Th17 (CD45RO+CXCR3−CCR4+CCR6+) [20], Tregs (CD45RO+CD25+CD127low) [21] and Tfh-like (CXCR5+PD1+) cells [22,23] (Fig. 3a). Proportions of SAMHD1low cells were comparable in HIV-negative and HIV-positive individuals in all subsets except Th17 (Fig. 3b and c). Indeed, 12.22 ± 3.01% of Th17 cells expressed low levels of SAMHD1 in HIV-negative controls as compared with 6.42 ± 4.39% in HIV+cART+ (P < 0.001), 5.50 ± 4.30% in HIV+cART− (P < 0.01) and 8.56 ± 2.20% in HIV+EC (P > 0.05) individuals (Fig. 3c). Moreover, Th17 cells were enriched in the SAMHD1low compartment compared with SAMHD1+, and there was a significant decrease of SAMHD1low cells among Th17 in HIV+ individuals [18.38 ± 6.37% in HIV− vs. 10.66 ± 5.77% in HIV+cART+ (P < 0.001), 7.11 ± 6.62% in HIV+cART− (P < 0.001) and 14.19 ± 3.41% in HIV+EC (P > 0.05); Fig. 3d]. The proportions of other Th subsets within SAMHD1low cells did not vary noticeably between our groups of HIV-negative and HIV-positive individuals, except for the Th2 population. Unlike for Th17 cells, however, we found lower proportions of Th2 cells in both SAMHD1low and SAMHD1+ compartments in HIV-infected individuals as compared with controls.

Fig. 3.

SAMHD1low T-helper 17 cells are preferentially depleted during HIV-1 infection.

Fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells from HIV-1-negative (HIV−, n = 13) or HIV-1-infected individuals treated (cART+ HIV+, n = 17), nontreated (cART− HIV+, n = 5) or elite controllers (HIV+ EC, n = 6) were stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD45RO, anti-CXCR3, anti-CCR4, anti-CCR6 or anti-CD127 and anti-CD25 or anti-CXCR5 and anti-PD1, and anti-SAMHD1. Aqua Vivid was included in the procedure to remove dead cells from the analysis. (a) Gating strategy for memory T helper 1 (Th1: CD45RO+CXCR3+CCR4−CCR6−), Th1/Th17 (CD45RO+CXCR3+CCR4−CCR6+), Th2 (CD45RO+CXCR3−CCR4+CCR6−), Th17 (CD45RO+CXCR3−CCR4+CCR6+), Treg (CD45RO+CD127lowCD25hi) and Tfh-like (CD45RO+CXCR5+PD1+) CD4+ T cells. (b) Representative dot-plots of SAMHD1 expression within the Th17 subset gated as in (a) from an HIV-1 negative (HIV-), HIV-1 infected individuals treated (cART+ HIV+), nontreated (cART- HIV+) and elite-controllers (HIV+ EC). (c) Percentages of SAMHD1low cells among Th17, Th1/17, Th1, Th2, Treg and Tfh-like CD4+ T-cells. (d) Percentages of Th17, Th1/17, Th1, Th2, Treg and follicular helper T (Tfh) like cells among gated SAMHD1+ and SAMHD1low CD4+ T cells. Data represent median with 25th–75th interquartile range with means displayed as +. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001, two-way analysis of variance tests followed by Bonferroni posttests.

Consistent with their preferential depletion during HIV-1 infection [16–19], our results suggest that higher susceptibility of Th17 cells to HIV-1 infection may be linked to a lower expression of SAMHD1.

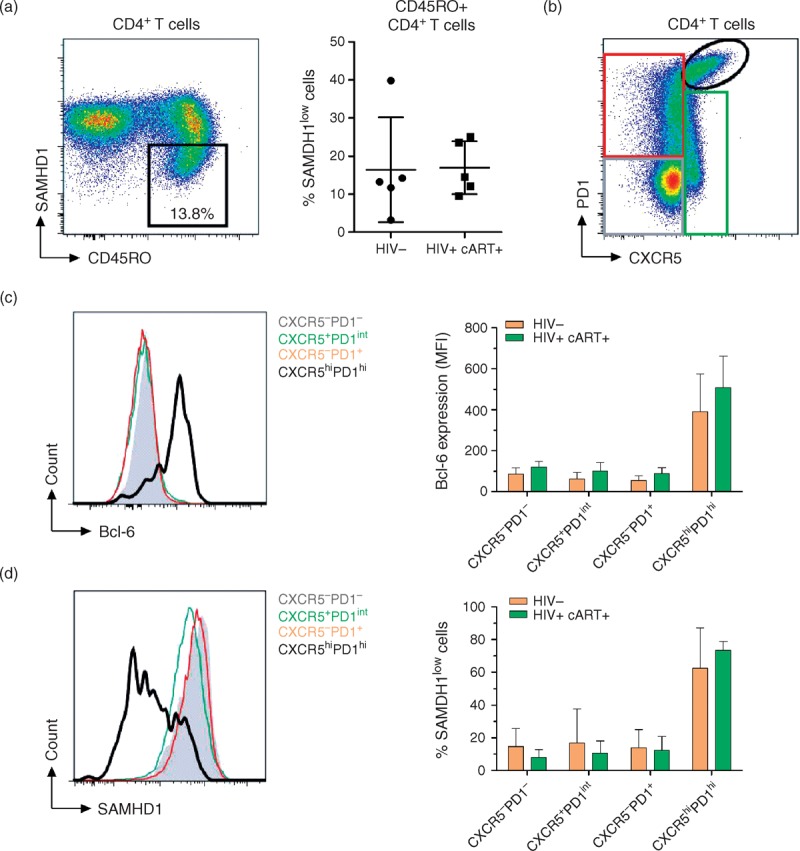

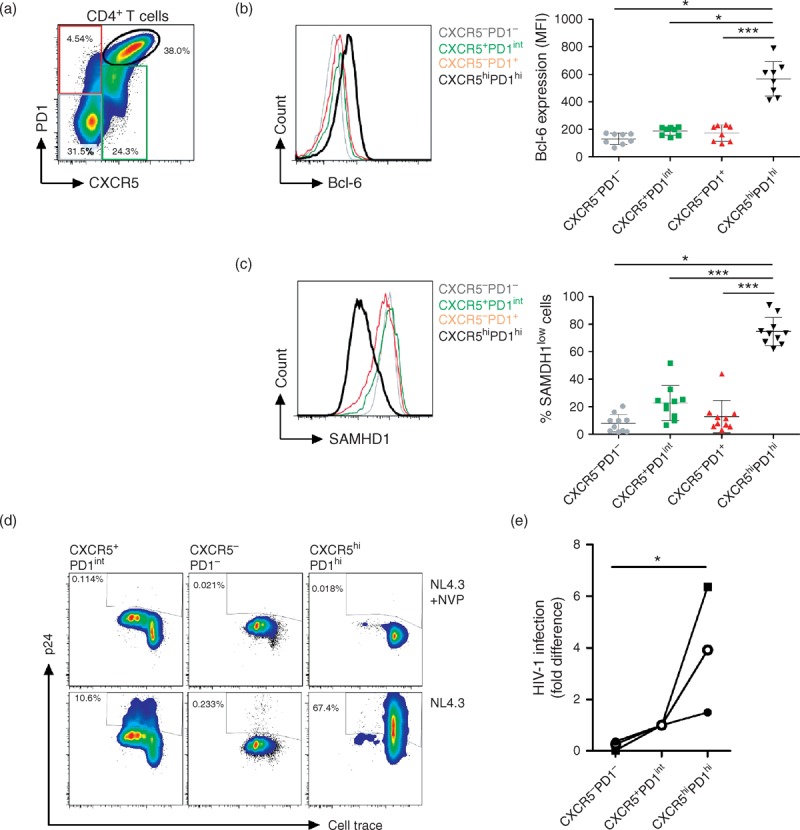

Follicular helper T cells from secondary lymphoid organs express low levels of SAMHD1 and are highly susceptible to HIV infection

Recent data indicated that CXCR5+PD1hi Tfh cells in the lymph nodes were more susceptible to HIV-1 infection [24,25]. We investigated the presence of SAMHD1lowCD4+ T cells in lymph nodes from both HIV-negative and HIV-positive cART-treated individuals (Fig. 4a). Flow cytometry analyses revealed that CXCR5+PD1hi Tfh cells were mostly SAMHD1low (Fig. 4a and b). The high levels of the transcription factor Bcl-6 in CXCR5+PD1hiCD4+ T cells from both groups further demonstrate that these cells are indeed Tfh cells (Fig. 4c). The frequency of CXCR5+PD1hi Tfh cells was not significantly different between treated-HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals (data not shown), as described earlier [24,25]. Tfh from HIV-1-infected individuals produced higher levels of interleukin-21 and lower interleukin-17 as compared with HIV-negative individuals, whereas no difference in interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-2 production was found (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 8).

Fig. 4.

Follicular helper T CD4+ T cells from lymph nodes express low levels of SAMHD1.

LNMCs from HIV-negative (n = 6) and ART-treated HIV-1-infected individuals (n = 6) were stained for CD3, CD4, CXCR5, PD1, Bcl-6, SAMHD1 and Vivid. (a) Representative dotplots displaying CD45RO and SAMHD1 expression with the gating strategy for SAMHD1low cells on gated live CD4+ T lymphocytes. Left panel display the percentages of SAMHD1low cells among CD45RO+CD4+ T cells in HIV negative and treated-HIV-positive individuals. (b) Representative dot plots displaying PD1 and CXCR5 expression with gating strategy used. (c) Representative histogram showing Bcl-6 expression (left panel), and mean fluorescence intensity of Bcl-6 expression (right panel) in gated CXCR5−PD1−, CXCR5+PD1int, CXCR5−PD1+ and CXCR5hiPD1hi CD4+ T-cell subpopulations. (d) Representative histogram showing SAMHD1 expression (left panel), and percentages of SAMHD1low cells (right panel) in gated CXCR5−PD1−, CXCR5+PD1int, CXCR5−PD1+ and CXCR5hiPD1hi CD4+ T-cell subpopulations.

For further analysis, due to the scarcity of lymph nodes samples from healthy individuals, we used tonsils from HIV-negative individuals undergoing tonsillectomy. Tonsilar Tfh cells (CXCR5+PD1hiBcl-6+), similar to Tfh from lymph nodes, expressed lower levels of SAMHD1 at both protein and mRNA levels when compared with CXCR5−PD1−, CXCR5+PD1int and CXCR5−PD1+ (Fig. 5a–c, and Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 9). Moreover, CXCR5+PD1hiBcl-6+SAMHD1low cells were Foxp3-negative, ruling out their regulatory Tfh phenotype and function [26]. They also expressed low levels of PRDM1/Blimp-1, the transcription factor that is mutually antagonistic with Bcl-6 [27]. CXCR5+PD1hi cells expressed low levels of CD26, high levels of CD38, CD161, CD278 and CD152, and are enriched in Ki67+ cells (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 10a), confirming their activated phenotype, in line with their function in the germinal center [28]. We have also found Tfh cells to express high and intermediate levels of CXCR4 and CCR5, respectively (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 10B). In addition and in line with recent studies [24,29,30], sorted CXCR5+PD1hi cells did not proliferate to the same extent as CXCR5−PD1−, CXCR5+PD1int and CXCR5−PD1+. (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 11).

Fig. 5.

Follicular helper T CD4+ T cells from tonsils display similar phenotype as from lymph nodes and are highly susceptible to HIV-1 infection in vitro.

Cells were mechanically isolated from human tonsils (n = 10) and stained for CXCR5, PD1, SAMHD1 and Bcl-6. (a) Representative dot-plot of CXCR5 and PD1 expression on gated live CD4+CD3+ lymphocytes from tonsils showing the gating strategy used for the analysis and the sorting of the cells. (b) Representative histogram and individual levels of Bcl-6 expression measured as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) on gated populations. (c) Representative histogram and individual percentages of SAMHD1low cells on gated populations. (d) CD4+ T cells from tonsils were sorted according to CXCR5 and PD1 expression and infected with 100 ng NL4.3 ± Nevirapine for 2 h and cultured on anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs (2 μg/ml) precoated plate for 3 days. Intracellular p24 and SAMHD1 staining were performed together with Aqua Vivid. Data are representative of one out of three independent experiments. (e) Individual-fold differences in HIV-1 infection of tonsilar sorted CD4+ T cells (n = 3). The CXCR5+PD1int infection rate as measured by intracellular p24 was used for the normalization. ∗P < 0.05, 1-way analysis of variance tests followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test.

To determine whether Tfh cells are more sensitive to HIV-1 infection, we infected in-vitro-sorted subsets with the HIV-1 NL4.3-strain. Data illustrated in Fig. 5d and e show that in-vitro-infected CXCR5+PD1hi Tfh cells have higher levels of intracellular p24 than CXCR5−PD1− and CXCR5+PD1int cells. Taken together these results suggest that low SAMHD1 expression in CXCR5+PD1hi Tfh cells might explain their increased susceptibility to HIV-1.

Discussion

Although SAMHD1 restriction activity toward HIV-1 infection is well established in vitro[5,6,12], its importance in the course of HIV-1 pathogenesis remains largely unknown. We demonstrate here that SAMHD1 expression is regulated after T-cell activation and that SAMHD1lowCD4+ T cells are preferentially susceptible to HIV-1 infection. Our results enlighten a possible role of SAMHD1 in the CD4+ T-cell depletion occurring in HIV-1-infected individuals.

We show that during CD4+ T-cell division, there is a downregulation of SAMHD1 at both mRNA and protein levels. Importantly, the decreased SAMHD1 expression during CD4+ T-cell proliferation correlated with an increased HIV-1 infection in vitro. Therefore, whereas SAMHD1 phosphorylation is an important determinant for HIV-1 restriction [9–12], we show that the protein expression, downregulated after T-cell activation, lead also to an increased susceptibility of CD4+ T cells to HIV-1 infection.

The mechanisms of CD4+ T-cell depletion during HIV-1 pathogenesis are multiple and remain a field of constant scientific investigation. It has been shown that the best correlate for CD4+ T-cell decline in HIV-1-infected individuals is the level of immune activation [31–33]. As SAMHD1 expression is modulated by CD4+ T-cell activation in vitro, we wondered if similar mechanisms could take place in vivo. By measuring SAMHD1 expression in peripheral CD4+ T cells, we reveal that a subset of memory cells displays low levels of SAMHD1 when compared with the majority of CD4+ T cells. SAMHD1lowCD4+ T cells are enriched in differentiated effector CD4+ T cells, the primary targets of HIV-1 [34]. In line with this, we found SAMHD1lowCD4+ T cells to be depleted in HIV-1-infected individuals, as compared with healthy controls, a finding consistent with SAMHD1 being a restriction factor for HIV-1 infection. Of note, we did not observe any differential expression of SAMHD1 between our different groups of HIV-infected individuals, in contrast to a recent study showing an increased SAMHD1-mRNA expression in EC mononuclear cells [35]. Our results strongly suggest that SAMHD1lowCD4+ T cells are depleted in HIV-1-infected individuals and are not recovered after ART initiation.

Notably, we found that peripheral SAMHD1lowCD4+ T cells express higher levels of Ki67 ex vivo, indicating that they are enriched in cycling cells. Memory SAMHD1lowCD4+ T cells also displayed higher expression of the activation markers CD38, HLA-DR and PD-1 as compared with SAMHD1+ cells. These results confirm that T-cell activation in vivo can also induce SAMHD1 downregulation. Thus, we uncover a new mechanism that may account for the high susceptibility toward HIV-1 infection of rapidly proliferating effector/memory CD4+ T cells. It might also be of interest to understand the molecular determinants modulating SAMHD1 expression. In particular, as some transcriptional factors are important for HIV-1 replication [36,37], the study of their relation with SAMHD1 expression may be of importance.

It is known that memory CD4+ T cells, the main targets of HIV-1 [38], are heterogeneous in their susceptibility to infection. Among the various subsets of CD4+ T cells, Th17 cells are presumed to be the most susceptible to HIV-1 infection and are preferentially depleted in infected individuals [16–19,39]. We found that Th17 cells exhibit the lowest levels of SAMHD1 in HIV-negative individuals. In addition, SAMHD1low Th17 cells are preferentially decreased in HIV-infected individuals as compared with controls, whereas SAMHD1+ Th17 cells were not affected. Unlike for Th17 cells, we found lower proportions of Th2 cells in both SAMHD1low and SAMHD1+ compartments, in HIV-infected individuals as compared with controls. These results suggest that the low levels of Th2 cell are independent of SAMHD1 expression and are more likely the consequence of antiviral immune responses. Our observation that SAMHD1low Th17 cells were depleted in the blood of HIV-infected individuals but preserved in elite controllers brings to light a potential mechanistic link between loss of Th17, lack of SAMHD1 and HIV-1 infection. These results are in line with recent studies showing a role for SAMHD1 in the permissiveness of CD4+ memory T cells with stem cell-like properties (TSCM) to HIV-1 infection [40,41].

Lymphoid tissues are an important site for HIV-1 replication, with Tfh cells exhibiting the highest levels of viral replication, and thus contributing to HIV persistence [24,25]. In nontreated HIV-1-infected individuals, despite high levels of viral replication, Tfh cell numbers are increased and act as an important contributor to the HIV-1 reservoir in vivo[24,25]. We demonstrate here that lymph nodes CXCR5hiPD1hiBcl-6+ Tfh cells lack SAMHD1 expression. Similar low expression of SAMHD1 was found in tonsilar Tfh cells and was associated with higher susceptibility toward HIV-1 infection. Indeed, non-Tfh CD4+ T-cell subsets that displayed higher expression levels of SAMHD1 exhibited lower HIV-1 infection. Of note, the discrepancies between lymph nodes Tfh and peripheral Tfh-like cells corroborate the interconnection between SAMHD1 levels and T-cell activation. Indeed, Tfh cells expressing Bcl-6 are found in the germinal center, specialized anatomic compartment of lymphoid tissues, and support B cell differentiation into plasma cells and the generation of potent antibody responses [28]. Tfh-like cells found in periphery are thought to arise from the differentiation of lymphoid Tfh into memory-like cells [42]. The Tfh-like resting phenotype would thus coincide with a high expression of SAMHD1. As Tfh functions are impaired during HIV-1 infection [43], a better understanding of molecular determinants leading to SAMHD1 modulation in Tfh cells may provide important insights indispensable for the generation of an efficient therapeutic vaccine.

Our work provides evidence that the lack of SAMHD1 expression plays an important role in the susceptibility of differentiated memory CD4+ T-cell subsets to HIV-1 infection in vivo. The understanding of SAMHD1 expression and its modulation may open new avenues for HIV research toward an HIV cure.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patients who participated in the study. They also thank Dr J. Zaunders for editing the manuscript, P. Tisserand for technical assistance, A. Guguin and A. Henry from IMRB facility for cell sorting.

Author contributions: N.R. designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; V.B. performed experiments, participated to discussions and edited the manuscript; D.A. performed experiments; C.L. performed experiments; J.S.Z.W. provided lymph nodes samples and edited the manuscript; J.V.L. provided lymph nodes samples and edited the manuscript; M.B. provided lymph nodes samples; O.S. provided crucial reagents and edited the manuscript; H.H. analyzed the data and edited the manuscript; J.D.L. organized patients recruitment and provided blood samples; J.B. participated to discussions and edited the manuscript; Y.L. organized patients recruitment, provided blood samples, participated to discussions and edited the manuscript; N.S. conceived the study, designed and supervised all experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Source of funding: This study was funded by the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche sur le SIDA et les hepatites virales (A.N.R.S.), the Vaccine Research Institute (V.R.I.) and the German Center for Infectious Disease Research.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Douek DC, Brenchley JM, Betts MR, Ambrozak DR, Hill BJ, Okamoto Y, et al. HIV preferentially infects HIV-specific CD4+ T cells. Nature 2002; 417:95–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDougal JS, Cort SP, Kennedy MS, Cabridilla CD, Feorino PM, Francis DP, et al. Immunoassay for the detection and quantitation of infectious human retrovirus, lymphadenopathy-associated virus (LAV). J Immunol Methods 1985; 76:171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Margolick JB, Volkman DJ, Folks TM, Fauci AS. Amplification of HTLV-III/LAV infection by antigen-induced activation of T cells and direct suppression by virus of lymphocyte blastogenic responses. J Immunol 1987; 138:1719–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, Swanson SK, Kesik-Brodacka M, Srivastava S, et al. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature 2011; 474:658–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, Ringeard M, Chable-Bessia C, Ségéral E, et al. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature 2011; 474:654–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldauf H-M, Pan X, Erikson E, Schmidt S, Daddacha W, Burggraf M, et al. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4(+) T cells. Nat Med 2012; 18:1682–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Descours B, Cribier A, Chable-Bessia C, Ayinde D, Rice G, Crow Y, et al. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 reverse transcription in quiescent CD4(+) T-cells. Retrovirology 2012; 9:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lahouassa H, Daddacha W, Hofmann H, Ayinde D, Logue EC, Dragin L, et al. SAMHD1 restricts the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by depleting the intracellular pool of deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Nat Immunol 2012; 13:223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White TE, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Valle-Casuso JC, Amie S, Nguyen LA, Kim B, et al. The retroviral restriction ability of SAMHD1, but not its deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase activity, is regulated by phosphorylation. Cell Host Microbe 2013; 13:441–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cribier A, Descours B, Valadão ALC, Laguette N, Benkirane M. Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 by cyclin A2/CDK1 regulates its restriction activity toward HIV-1. Cell Rep 2013; 3:1036–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welbourn S, Dutta SM, Semmes OJ, Strebel K. Restriction of virus infection but not catalytic dNTPase activity is regulated by phosphorylation of SAMHD1. J Virol 2013; 87:11516–11524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryoo J, Choi J, Oh C, Kim S, Seo M, Kim S-Y, et al. The ribonuclease activity of SAMHD1 is required for HIV-1 restriction. Nat Med 2014; 20:936–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Silva S, Wang F, Hake TS, Porcu P, Wong HK, Wu L. Downregulation of SAMHD1 expression correlates with promoter DNA methylation in Sézary syndrome patients. J Invest Dermatol 2014; 134:562–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roesch F, Meziane O, Kula A, Nisole S, Porrot F, Anderson I, et al. Hyperthermia stimulates HIV-1 replication. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1002792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruffin N. Chronic immune activation and lymphocyte apoptosis during HIV-1 infection. Karolinska Institutet; 2012. http://hdl.handle.net/10616/40875 [accessed August 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monteiro P, Gosselin A, Wacleche VS, El-Far M, Said EA, Kared H, et al. Memory CCR6+CD4+ T cells are preferential targets for productive HIV type 1 infection regardless of their expression of integrin β7. J Immunol 2011; 186:4618–4630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gosselin A, Monteiro P, Chomont N, Diaz-Griffero F, Said EA, Fonseca S, et al. Peripheral blood CCR4+CCR6+ and CXCR3+CCR6+CD4+ T cells are highly permissive to HIV-1 infection. J Immunol 2010; 184:1604–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvarez Y, Tuen M, Shen G, Nawaz F, Arthos J, Wolff MJ, et al. Preferential HIV infection of CCR6+ Th17 cells is associated with higher levels of virus receptor expression and lack of CCR5 ligands. J Virol 2013; 87:10843–10854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Hed A, Khaitan A, Kozhaya L, Manel N, Daskalakis D, Borkowsky W, et al. Susceptibility of human Th17 cells to human immunodeficiency virus and their perturbation during infection. J Infect Dis 2010; 201:843–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Rivino L, Geginat J, Jarrossay D, Gattorno M, Lanzavecchia A, et al. Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat Immunol 2007; 8:639–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seddiki N, Santner-Nanan B, Martinson J, Zaunders J, Sasson S, Landay A, et al. Expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-7 receptors discriminates between human regulatory and activated T cells. J Exp Med 2006; 203:1693–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morita R, Schmitt N, Bentebibel S-E, Ranganathan R, Bourdery L, Zurawski G, et al. Human blood CXCR5(+)CD4(+) T cells are counterparts of T follicular cells and contain specific subsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity 2011; 34:108–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaerli P, Willimann K, Lang AB, Lipp M, Loetscher P, Moser B. CXC chemokine receptor 5 expression defines follicular homing T cells with B cell helper function. J Exp Med 2000; 192:1553–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perreau M, Savoye A-L, De Crignis E, Corpataux J-M, Cubas R, Haddad EK, et al. Follicular helper T cells serve as the major CD4 T cell compartment for HIV-1 infection, replication, and production. J Exp Med 2013; 210:143–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindqvist M. Expansion of HIV-specific T follicular helper cells in chronic HIV infection. J Clin Invest 2012; 122:3271–3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linterman MA, Pierson W, Lee SK, Kallies A, Kawamoto S, Rayner TF, et al. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat Med 2011; 17:975–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston RJ, Poholek AC, DiToro D, Yusuf I, Eto D, Barnett B, et al. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science 2009; 325:1006–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tangye SG, Ma CS, Brink R, Deenick EK. The good, the bad and the ugly: TFH cells in human health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2013; 13:412–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petrovas C, Yamamoto T, Gerner MY, Boswell KL, Wloka K, Smith EC, et al. CD4 T follicular helper cell dynamics during SIV infection. J Clin Invest 2012; 122:3281–3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C, Hillsamer P, Kim CH. Phenotype, effector function, and tissue localization of PD-1-expressing human follicular helper T cell subsets. BMC Immunol 2011; 12:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deeks SG, Kitchen CMR, Liu L, Guo H, Gascon R, Narváez AB, et al. Immune activation set point during early HIV infection predicts subsequent CD4+ T-cell changes independent of viral load. Blood 2004; 104:942–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leng Q, Borkow G, Weisman Z, Stein M, Kalinkovich A, Bentwich Z. Immune activation correlates better than HIV plasma viral load with CD4 T-cell decline during HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2001; 27:389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sousa AE, Carneiro J, Meier-Schellersheim M, Grossman Z, Victorino RMM. CD4 T cell depletion is linked directly to immune activation in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 and HIV-2 but only indirectly to the viral load. J Immunol 2002; 169:3400–3406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chomont N, El-Far M, Ancuta P, Trautmann L, Procopio FA, Yassine-Diab B, et al. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat Med 2009; 15:893–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riveira-Muñoz E, Ruiz A, Pauls E, Permanyer M, Badia R, Mothe B, et al. Increased expression of SAMHD1 in a subset of HIV-1 elite controllers. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69:3057–3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karn J, Stoltzfus CM. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of HIV-1 gene expression. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2: a006916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Victoriano AFB, Okamoto T. Transcriptional control of HIV replication by multiple modulators and their implication for a novel antiviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2012; 28:125–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnittman SM, Lane HC, Greenhouse J, Justement JS, Baseler M, Fauci AS. Preferential infection of CD4+ memory T cells by human immunodeficiency virus type 1: evidence for a role in the selective T-cell functional defects observed in infected individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990; 87:6058–6062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brenchley JM, Paiardini M, Knox KS, Asher AI, Cervasi B, Asher TE, et al. Differential Th17 CD4 T-cell depletion in pathogenic and nonpathogenic lentiviral infections. Blood 2008; 112:2826–2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buzon MJ, Sun H, Li C, Shaw A, Seiss K, Ouyang Z, et al. HIV-1 persistence in CD4+ T cells with stem cell-like properties. Nat Med 2014; 20:139–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabler CO, Lucera MB, Haqqani AA, McDonald DJ, Migueles SA, Connors M, et al. CD4+ memory stem cells are infected by HIV-1 in a manner regulated in part by SAMHD1 expression. J Virol 2014; 88:4976–4986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmitt N, Bentebibel S-E, Ueno H. Phenotype and functions of memory Tfh cells in human blood. Trends Immunol 2014; 35:436–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cubas R, Perreau M. The dysfunction of T follicular helper cells. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2014; 9:485–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.