Background: Host factors regulating hepatitis B virus (HBV) entry receptors are not well defined.

Results: Chemical screening identified that retinoic acid receptor (RAR) regulates sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) expression and supports HBV infection.

Conclusion: RAR regulates NTCP expression and thereby supports HBV infection.

Significance: RAR regulation of NTCP can be a target for preventing HBV infection.

Keywords: Chemical Biology, Hepatitis Virus, Retinoid, Transcription, Transporter, HBV, NTCP, RAR, Infection, Permissive

Abstract

Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) is an entry receptor for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and is regarded as one of the determinants that confer HBV permissiveness to host cells. However, how host factors regulate the ability of NTCP to support HBV infection is largely unknown. We aimed to identify the host signaling that regulated NTCP expression and thereby permissiveness to HBV. Here, a cell-based chemical screening method identified that Ro41-5253 decreased host susceptibility to HBV infection. Pretreatment with Ro41-5253 inhibited the viral entry process without affecting HBV replication. Intriguingly, Ro41-5253 reduced expression of both NTCP mRNA and protein. We found that retinoic acid receptor (RAR) regulated the promoter activity of the human NTCP (hNTCP) gene and that Ro41-5253 repressed the hNTCP promoter by antagonizing RAR. RAR recruited to the hNTCP promoter region, and nucleotides −112 to −96 of the hNTCP was suggested to be critical for RAR-mediated transcriptional activation. HBV susceptibility was decreased in pharmacologically RAR-inactivated cells. CD2665 showed a stronger anti-HBV potential and disrupted the spread of HBV infection that was achieved by continuous reproduction of the whole HBV life cycle. In addition, this mechanism was significant for drug development, as antagonization of RAR blocked infection of multiple HBV genotypes and also a clinically relevant HBV mutant that was resistant to nucleoside analogs. Thus, RAR is crucial for regulating NTCP expression that determines permissiveness to HBV infection. This is the first demonstration showing host regulation of NTCP to support HBV infection.

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV)2 infection is a major public health problem, as the virus chronically infects ∼240 million people worldwide (1–3). Chronic HBV infection elevates the risk for developing liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (4–6). Currently, two classes of antiviral agents are available to combat chronic HBV infection. First, interferon (IFN)-based drugs, including IFNα and pegylated-IFNα, modulate host immune function and/or directly inhibit HBV replication in hepatocytes (7, 8). However, the antiviral efficacy of IFN-based drugs is restricted to less than 40% (9, 10). Second, nucleos(t)ide analogs, including lamivudine (LMV), adefovir, entecavir (ETV), tenofovir, and telbivudine suppress HBV by inhibiting the viral reverse transcriptase (11, 12). Although they can provide significant clinical improvement, long term therapy with nucleos(t)ide analogs often results in the selection of drug-resistant mutations in the target gene, which limits the treatment outcome. For example, in patients treated with ETV, at least three mutations can arise in the reverse transcriptase sequence of the polymerase L180M and M204V plus either one of Thr-184, Ser-202, or Met-250 codon changes to acquire drug resistance (13). Therefore, development of new anti-HBV agents targeting other molecules requires elucidation of the molecular mechanisms underlying the HBV life cycle.

HBV infection of hepatocytes involves multiple steps. The initial viral attachment to the host cell surface starts with a low affinity binding involving heparan sulfate proteoglycans, and the following viral entry is mediated by a specific interaction between HBV and its host receptor(s) (14). Recently, sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) was reported as a functional receptor for HBV (15). NTCP interacts with HBV large surface protein (HBs) to mediate viral attachment and the subsequent entry step. NTCP, also known as solute carrier protein 10A1 (SLC10A1), is physiologically a sodium-dependent transporter for bile salts located on the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes (16). In the liver, hepatocytes take up bile salts from the portal blood and secrete them into bile for enterohepatic circulation, and NTCP-mediated uptake of bile salts into hepatocytes occurs largely in a sodium-dependent manner. Although NTCP is abundant in freshly isolated primary hepatocytes, it is weakly or no longer expressed in most cell lines such as HepG2 and Huh-7, and these cells rarely support HBV infection (17, 18). In contrast, primary human hepatocytes, primary tupaia hepatocyte, and differentiated HepaRG cells, which are susceptible to HBV infection, express significant levels of NTCP (19). Thus, elucidation of the regulatory mechanisms for NTCP gene expression is important for understanding the HBV susceptibility of host cells as well as for developing a new anti-HBV strategy. HBV entry inhibitors are expected to be useful for preventing de novo infection after liver transplantation, for post-exposure prophylaxis, or for vertical transmission by short term treatment (20, 21).

In this study, we used a HepaRG-based HBV infection system to screen for small molecules capable of decreasing HBV infection. We found that pretreatment of host cells with Ro41-5253 reduced HBV infection. Ro41-5253 reduced NTCP expression by repressing the promoter activity of the human NTCP (hNTCP) gene. Retinoic acid receptor (RAR) played a crucial role in regulating the promoter activity of hNTCP, and Ro41-5253 antagonized RAR to reduce NTCP transcription and consequently HBV infection. This and other RAR inhibitors showed anti-HBV activity against different genotypes and an HBV nucleoside analog-resistant mutant and moreover inhibited the spread of HBV. This study clarified one of the mechanisms for gene regulation of NTCP to support HBV permissiveness, and it also suggests a novel concept whereby manipulation of this regulation machinery can be useful for preventing HBV infection.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Heparin was obtained from Mochida Pharmaceutical. Lamivudine, cyclosporin A, all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA), and TO901317 were obtained from Sigma. Entecavir was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Ro41-5253 was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences. PreS1-lipopeptide and FITC-labeled preS1 were synthesized by CS Bio. IL-1β was purchased from PeproTech. CD2665, BMS195614, BMS493, and MM11253 were purchased from Tocris Bioscience.

Cell Culture

HepaRG cells (BIOPREDIC) and primary human hepatocytes (Phoenixbio) were cultured as described previously (19). HepG2 and HepAD38 cells (kindly provided by Dr. Christoph Seeger at Fox Chase Cancer Center) (22) were cultured with DMEM/F-12 + GlutaMAX (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10 mm HEPES (Invitrogen), 200 units/ml penicillin, 200 μg/ml streptomycin, 10% FBS, and 5 μg/ml insulin. HuS-E/2 cells (kindly provided by Dr. Kunitada Shimotohno at National Center for Global Health and Medicine) were cultured as described previously (23).

Plasmid Construction

phNTCP-Gluc, pTK-Rluc was purchased from GeneCopoeia and Promega, respectively. pRARE-Fluc was generated as described (25). For constructing phNTCP-Gluc carrying a mutation in a putative RARE (nt −491 to −479), the DNA fragments were amplified by PCR using phNTCP-Gluc as a template with the following primer sets: F1, 5′-CAGATCTTGGAATTCCCAAAATC-3′ and 5′-GAGGGGATGTGTCCATTGAAATGTTAATGGGAGCTGAGAGGATGCCAGTATCCTCCCT-3′ and primer sets 5′-CTCTCAGCTCCCATTAACATTTCAATGGACACATCCCCTCCTGGAGGCCAGTGACATT-3′ and R6, 5′-CTCGGTACCAAGCTTTCCTTGTT-3′. The resultant products were further amplified by PCR with F1 and R6 and then inserted into the EcoRI/HindIII sites of phNTCP-Gluc to generate phNTCP Mut(−491 to −479)-Gluc. Other promoter mutants were prepared by the same method using the following primer sets: F1, 5′-GTGGGTTATCATTTGTTTCCCGAAAACATTAGAGTGAAAGGAGCTGGGTGTTGCCTTTGG-3′ and 5′-TCCTTTCACTCTAATGTTTTCGGGAAACAAATGATAACCCACTGGACATGGGGAGGGCAC-3′; R6 for −368 to −356; F1 and 5′-AATCTAGGTCCAGCCTATTTAAGTCCCTAAATTTCCTTTTCCCAGCTCCGCTCTTGATTCCTT-3′, 5′-CTGGGAAAAGGAAATTTAGGGACTTAAATAGGCTGGACCTAGATTCAGGTGGGCCCTGGGCAG-3′, and R6 for −274 to −258; F1 and 5′-TTCTGGGCTTATTTCTATATTTTGCAATCCACTGAGTGTGCCTCATGGGCATTCATTC-3′, 5′-CACACTCAGTGGATTGCAAAATATAGAAATAAGCCCAGAAGCAGCAAAGTGACAAGGG-3′, and R6 for −179 to −167; F1 and 5′-AGCTCTCCCAAGCTCAAAGATAAATGCTAGTTTCCTGGGTGCTACTTGTACTCCTCCCTTGTC-3′, 5′-GTAGCACCCAGGAAACTAGCATTTATCTTTGAGCTTGGGAGAGCTAGGGCAGGCAGATAAGGT-3′, and R6 for −112 to −96, respectively. For constructing the hNTCP promoter carrying these five mutations (5-Mut), five DNA segments were amplified using the primers as follows: segment 1, F1 and 5′-GAGGGGATGTGTCCATGACC-3′; segment 2, 5′-AGCTCCTTTCACTCTCATGGGT-3′ and 5′-TCCTTTTCCCAGCTCCGC-3′; segment 3, 5′-GAGCTGGGAAAAGGAGCTGC-3′ and 5′-CCACTGAGTGTGCCTCATGG-3′; segment 4, 5′-AGGCACACTCAGTGGAGGG-3′ and 5′-CTGGGTGCTACTTGTACTCCTCC-3′; and segment 5, 5′-CAAGTAGCACCCAGGAATCCA-3′ and R6. For producing a deletion construct for the hNTCP promoter, phNTCP (−53 to +108)-Gluc, DNA fragment was amplified using the primer sets 5′-GGTGAATTCTGTTCCTCTTTGGGGCGACAGC-3′ and 5′-GGTGGTAAGCTTTCCTTGTTCTCCGGCTGACTCC-3′ and then inserted into the EcoRI and HindIII sites of phNTCP-Gluc.

HBV Preparation and Infection

HBV was prepared and infected as described (19). HBV used in this study was mainly derived from HepAD38 cells (22). For Fig. 8, A–E, we used concentrated (∼200-fold) media of HepG2 cells transfected with an expression plasmid for either HBV genotypes A, B, C, D or genotype C carrying mutations at L180M, S202G, and M204V (HBV/Aeus, HBV/Bj35s, HBV/C-AT, HBV/D-IND60, or HBV/C-AT(L180M/S202G/M204V)) (24) and infected into the cells at 2000 GEq/cell in the presence of 4% PEG8000 at 37 °C for 16 h as described previously (19). HBV for Fig. 8F (genotype C) was purchased from Phoenixbio.

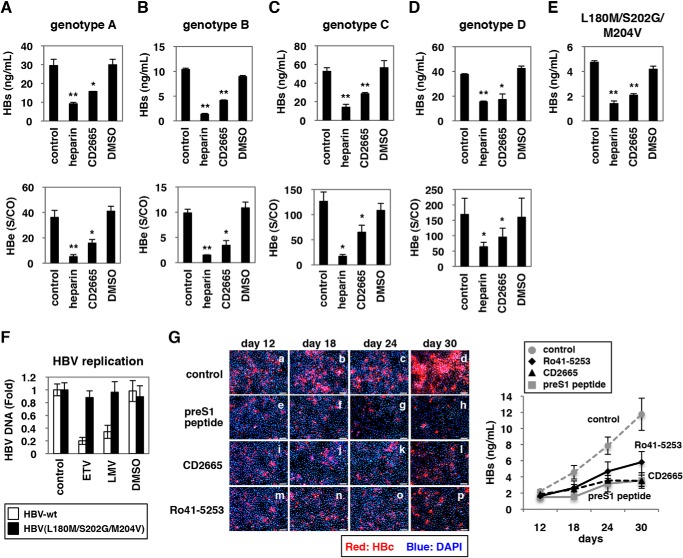

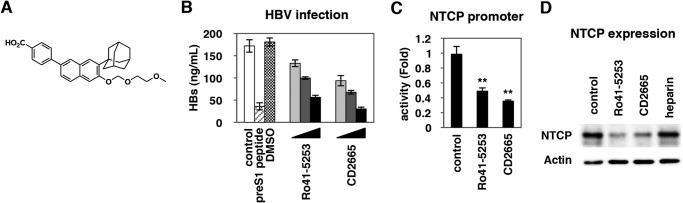

FIGURE 8.

CD2665 showed a pan-genotypic anti-HBV activity. A–E, primary human hepatocytes were pretreated with or without compounds (50 units/ml heparin, 20 μm CD2665, or 0.1% DMSO) and inoculated with different genotypes of HBV according to the scheme show in Fig. 1A. HBs (A–E) and HBe (A–D) antigen secreted into the culture supernatant was quantified by ELISA. Genotypes A (A), B (B), C (C), D (D), and an HBV carrying mutations (L180M/S202G/M204V) (E) were used as inoculum. F, HBV(L180M/S202G/M204V) was resistant to nucleoside analogs. HepG2 cells transfected with the expression plasmid for HBV/C-AT (white) or HBV/C-AT(L180M/S202G/M204V) (black) were treated with or without 1 μm ETV, 1 μm LMV, or 0.1% DMSO for 72 h. The cells were lysed, and the nucleocapsid-associated HBV DNAs were recovered. Relative values for HBV DNAs are indicated. G, continuous RAR inactivation could inhibit HBV spread. Freshly isolated primary human hepatocytes were pretreated with or without indicated compounds (1 μm preS1 peptide, 10 μm Ro41-5253, or 10 μm CD2665) and inoculated with HBV at day 0. After removing free viruses, primary human hepatocytes were cultured in the medium supplemented with the indicated compounds for up to 30 days postinfection. At 12, 18, 24, and 30 days postinfection, HBc protein in the cells (left panels, red) and HBs antigen secreted into the culture supernatant (right graph) were detected by immunofluorescence and ELISA, respectively. Red and blue signals in the left panels show the detection of HBc protein and nucleus, respectively. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t test (*, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01).

Real Time PCR and RT-PCR

Real time PCR for detecting HBV DNAs and cccDNA was performed as described (19). RT-PCR detection of mRNAs for NTCP, ASBT, SHP, and GAPDH was performed with one-step RNA PCR kit (TaKaRa) following the manufacturer's protocol with primer set 5′-AGGGAGGAGGTGGCAATCAAGAGTGG-3′ and 5′-CCGGCTGAAGAACATTGAGGCACTGG-3′ for NTCP, 5′-GTTGGCCTTGGTGATGTTCT-3′ and 5′-CGACCCAATAGGCCAAGATA-3′ for ASBT, 5′-CAGCTATGTGCACCTCATCG-3′ and 5′-CCAGAAGGACTCCAGACAGC-3′ for SHP, and 5′-CCATGGAGAAGGCTGGGG-3′ and 5′-CAAAGTTGTCATGGATGACC-3′ for GAPDH, respectively.

Immunofluorescence Analysis

Immunofluorescence was conducted essentially as described (25) using an anti-HBc antibody (DAKO, catalog no. B0586) at a dilution of 1:1000.

Detection of HBs and HBe Antigens

HBs and HBe antigens were detected by ELISA and chemiluminescence immunoassay, respectively, as described (19).

MTT Assay

The MTT cell viability assay was performed as described previously (19).

Southern Blot Analysis

Isolation of cellular DNA and Southern blot analysis to detect HBV DNAs were performed as described previously (19).

Immunoblot Analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously (26, 27). Anti-NTCP (Abcam) (1:2000 dilution), anti-RARα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (1:6000 dilution), anti-RARβ (Sigma) (1:6000 dilution), anti-RARγ (Abcam) (1:2000 dilution), anti-RXRα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (1:8000 dilution), and anti-actin (Sigma) (1:5000 dilution) antibodies were used for primary antibodies.

Flow Cytometry

1 × 106 primary human hepatocytes were incubated for 30 min with a 1:50 dilution of anti-NTCP antibody (Abcam) and then washed and incubated with a dye-labeled secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, Invitrogen) at 1:500 dilution in the dark. Staining and washing were carried out at 4 °C in PBS supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% sodium azide. The signals were analyzed with Cell Sorter SH8000 (Sony).

FITC-preS1 Peptide-binding Assay

Attachment of preS1 peptide with host cells was examined by preS1 binding assay essentially as described previously (28). HepaRG cells treated with or without Ro41-5253 (28) for 24 h or unlabeled preS1 peptide for 30 min were incubated with 40 nm FITC-labeled preS1 peptide (FITC-preS1) at 37 °C for 30 min. After washing the cells twice with culture medium and once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Then the cells were treated with 4% Block Ace (DS Pharma Biomedical) containing DAPI for 30 min.

Reporter Assay

HuS-E/2 cells were transfected with phNTCP-Gluc (GeneCopoeia), a reporter plasmid carrying the NTCP promoter sequence upstream of the Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) gene, and pSEAP (GeneCopoeia), expressing the secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) gene, together with or without expression plasmids for RARα, RARβ, RARγ, with RXRα using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 24 h post-transfection, cells were stimulated with the indicated compounds for a further 24 h. The activities for Gluc as well as for SEAP were measured using a Secrete-Pair Dual-Luminescence assay kit (GeneCopoeia) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and Gluc values normalized by SEAP are shown.

pRARE-Fluc, carrying three tandem repeats of RAR-binding elements upstream of firefly luciferase (Fluc), and pTK-Rluc (Promega), which carries herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter expressing Renilla luciferase (Rluc) (25), were used in dual-luciferase assays for detecting Fluc and Rluc. Fluc and Rluc were measured with Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and Fluc activities normalized by Rluc are shown.

For evaluating HBV transcription in Fig. 2B, we used a reporter construct carrying HBV enhancer I, II, and core promoter (nt 1039–1788) (“Enh I + II”) and that carrying enhancer II and core promoter (nt 1413–1788) (“Enh II”). These were constructed by inserting the corresponding sequences derived from a genotype D HBV in HepG2.2.15 cells into pGL4.28 vector (Promega). pGL3 promoter vector (Promega), which carries SV40 promoter (“SV40”) was used as a control.

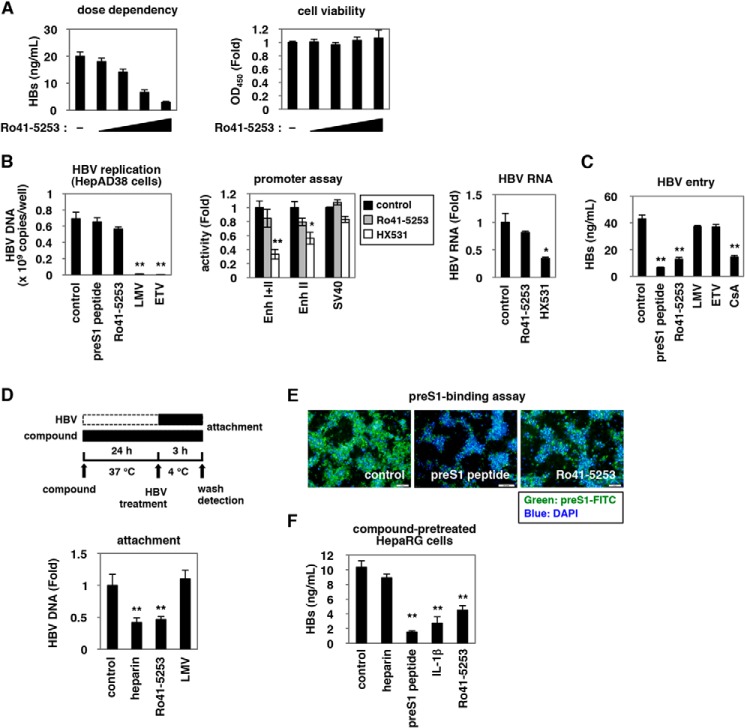

FIGURE 2.

Ro41-5253 decreased HBV entry. A, HepaRG cells were treated with or without various concentrations (2.5, 5, 10, and 20 μm) of Ro41-5253 followed by HBV infection according to the protocol shown in Fig. 1A. Secreted HBs was detected by ELISA (left panel). Cell viability was also determined by ELISA (right panel). B, left panel, nucleocapsid-associated HBV DNA in HepAD38 cells treated with the indicated compounds (200 nm preS1 peptide, 20 μm Ro41-5253, 1 μm lamivudine, or 1 μm entecavir) for 6 days without tetracycline was quantified by real time PCR. Middle panel, HepG2 cells transfected with the reporter plasmids carrying HBV Enhancer (Enh) I + II, HBV Enhancer II, or SV40 promoter (“Experimental Procedures”) were treated with or without Ro41-5253 or HX531 as a positive control to measure the luciferase activity. Right panel, HepG2.2.15 cells were treated with or without Ro41-5253 or HX531 for 6 days, and intracellular HBV RNA was quantified by real time RT-PCR. C, HepaRG cells were treated with or without indicated compounds (200 nm preS1 peptide, 20 μm Ro41-5253, 1 μm lamivudine, 1 μm entecavir, or 4 μm CsA) followed by HBV infection according to the protocol shown in Fig. 1A. D, upper scheme shows the experimental procedure for examining cell surface-bound HBV. The cells were pretreated with compounds (50 units/ml heparin, 20 μm Ro41-5253, or 1 μm lamivudine) at 37 °C for 24 h and then treated with HBV at 4 °C for 3 h to allow HBV attachment but not internalization into the cells. After removing free virus, cell surface HBV DNA was extracted and quantified by real time PCR. E, HepaRG cells pretreated with the indicated compounds (1 μm unconjugated preS1 peptide, 20 μm Ro41-5253) for 24 h were treated with 40 nm FITC-conjugated pre-S1 peptide (FITC-preS1) in the presence of compounds at 37 °C for 30 min. Green and blue signals show FITC-preS1 and nuclear staining, respectively. F, HepaRG cells pretreated with the indicated compounds (50 units/ml heparin, 200 nm preS1 peptide, 100 ng/ml IL-1β, or 20 μm Ro41-5253) for 24 h were used for the HBV infection assay, where HBV was inoculated for 16 h in the absence of the compounds. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t test (*, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

ChIP assay was performed using a Pierce-agarose ChIP kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Huh7-25 cells transfected with phNTCP-Gluc together with or without expression plasmids for FLAG-tagged RARa and for RXRa were treated with 5 mg/ml actinomycin D for 2 h. The cells were then washed and treated with or without 2 mm ATRA for 60 min. Formaldehyde cross-linked cells were lysed, digested with micrococcal nuclease, and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) or normal IgG. Input samples were also recovered without immunoprecipitation. DNA recovered from the immunoprecipitated or the input samples was amplified with primers 5′-CCCAGGGCCCACCTGAATCTA-3′ and 5′-TAGATTCAGGTGGGCCCTGGG-3′ for detection of NTCP.

RESULTS

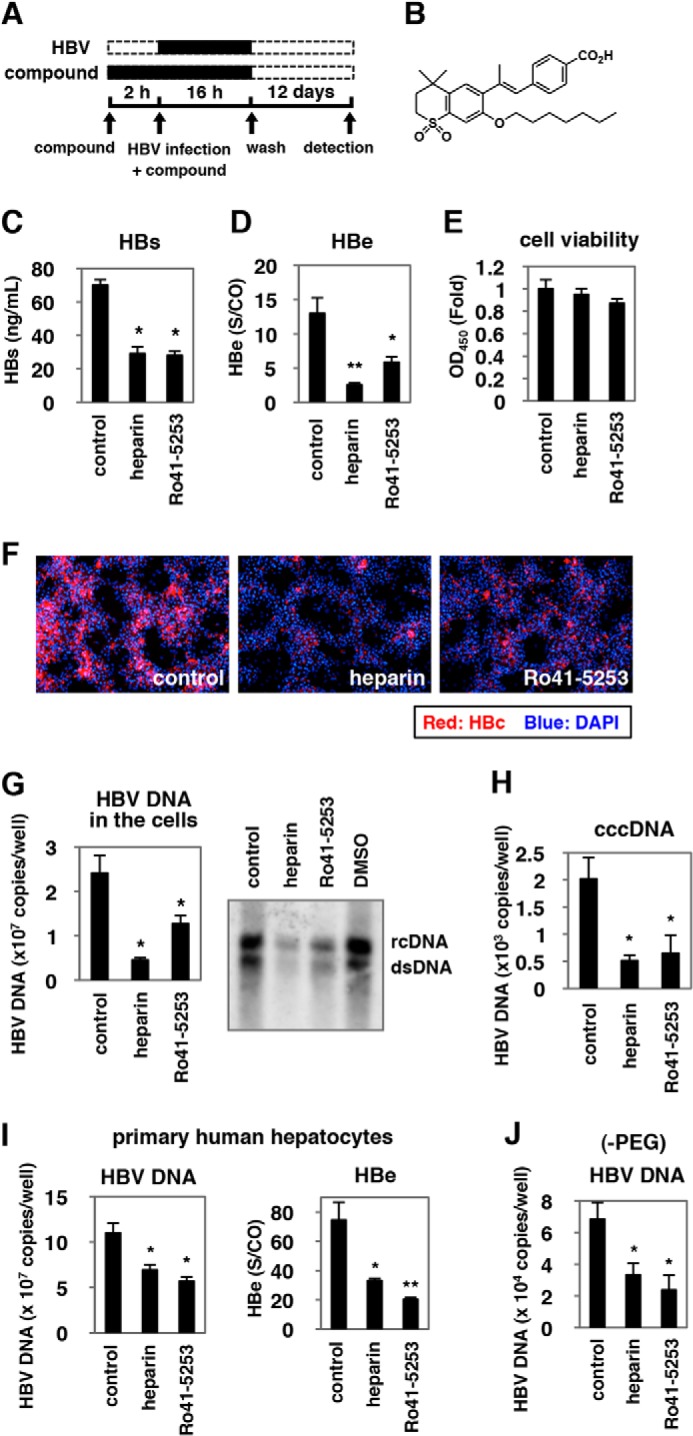

Anti-HBV Activity of Ro41-5253

We searched for small molecules capable of decreasing HBV infection in a cell-based chemical screening method using HBV-susceptible HepaRG cells (29). As a chemical library, we used a set of compounds for which bioactivity was already characterized (19). HepaRG cells were pretreated with compounds and then further incubated with HBV inoculum in the presence of compounds for 16 h (Fig. 1A). After removing free HBV and compounds by washing, the cells were cultured for an additional 12 days without compounds. For robust screening, HBV infection was monitored by ELISA quantification of HBs antigen secreted from the infected cells at 12 days postinfection. This screening revealed that HBs was significantly reduced by treatment with Ro41-5253 (Fig. 1B) as well as heparin, a competitive viral attachment inhibitor that served as a positive control (Fig. 1C) (14). HBe in the medium (Fig. 1D) as well as intracellular HBc protein (Fig. 1F), HBV replicative (Fig. 1G), and cccDNA (Fig. 1H) were consistently decreased by treatment with Ro41-5253, without serious cytotoxicity (Fig. 1E). This effect of Ro41-5253 was not limited to infection of HepaRG cells because we observed a similar anti-HBV effect in primary human hepatocytes (Fig. 1I). The anti-HBV effect of Ro41-5253 on HBV infection of primary human hepatocytes was also observed in the absence of PEG8000 (Fig. 1J), which is frequently used to enhance HBV infectivity in vitro (14, 29). These data suggest that Ro41-5253 treatment decreases hepatocyte susceptibility to HBV infection.

FIGURE 1.

Ro41-5253 decreased susceptibility to HBV infection. A, schematic representation of the schedule for treatment of HepaRG cells with compounds and infection with HBV. HepaRG cells were pretreated with compounds for 2 h and then inoculated with HBV in the presence of compounds for 16 h. After washing out the free HBV and compounds, cells were cultured in the absence of compounds for an additional 12 days followed by quantification of secreted HBs protein. Black and dashed bars indicate the interval for treatment and without treatment, respectively. B, chemical structure of Ro41-5253. C–E, HepaRG cells were treated with or without 10 μm Ro41-5253 or 50 units/ml heparin according to the protocol shown in A, and HBs (C) and HBe (D) antigens in the culture supernatant were measured. Cell viability was also examined by MTT assay (E). F–H, HBc protein (F), HBV DNAs (G), and cccDNA (H) in the cells according to the protocol shown in A were detected by immunofluorescence, real time PCR, and Southern blot analysis. Red and blue in F show the detection of HBc protein and nuclear staining, respectively. I and J, primary human hepatocytes were treated with the indicated compounds and infected with HBV in the presence (I) or absence (J) of PEG8000 according to the protocol shown in A. The levels of HBV DNA in the cells (I and J) and HBe antigen in the culture supernatant (I) were quantified. The data show the means of three independent experiments. Standard deviations are also shown as error bars. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

Reduced HBV Entry in Ro41-5253-treated Cells

Ro41-5253 decreased HBs secretion from infected cells in a dose-dependent manner without significant cytotoxicity (Fig. 2A). We next investigated which step in the HBV life cycle was blocked by Ro41-5253. The HBV life cycle can be divided into two phases as follows: 1) the early phase of infection, including attachment, internalization, nuclear import, and cccDNA formation, and 2) the following late phase representing HBV replication that includes transcription, pregenomic RNA encapsidation, reverse transcription, envelopment, and virus release (19, 20, 30–34). LMV and ETV, inhibitors of reverse transcriptase, dramatically decreased HBV DNA in HepAD38 cells (Fig. 2B, left panel), which can replicate HBV DNA but are resistant to infection (22). However, LMV and ETV did not show a significant effect in HepaRG-based infection (Fig. 1A), in contrast to the anti-HBV effect of CsA, an HBV entry inhibitor (Fig. 2C) (19, 35), suggesting that this infection assay could be used to evaluate the early phase of infection without the replication process, including the reverse transcription. Ro41-5253 was suggested to inhibit the early phase of infection prior to genome replication as an anti-HBV activity was evident in Fig. 2C but not in Fig. 2B. Moreover, Ro41-5253 had little effect on HBV transcription, which was monitored by a luciferase activity driven from the HBV enhancer I, II, and the core promoter (Fig. 2B, middle panel), and by the HBV RNA level in HepG2.2.15 cells, persistently producing HBV (Fig. 2B, right panel) (36). We then examined whether Ro41-5253 pretreatment affected viral attachment to host cells. To this end, HepaRG cells were exposed to HBV at 4 °C for 3 h, which allowed HBV attachment but not subsequent internalization (19) (Fig. 2D). After washing out free viruses, cell surface HBV DNA was extracted and quantified to evaluate HBV cell attachment (Fig. 2D). Pretreatment with Ro41-5253 significantly reduced HBV DNA attached to the cell surface, as did heparin (Fig. 2D). In a preS1 binding assay, where FITC-labeled preS1 lipopeptide was used as a marker for HBV attachment to the cell surface, Ro41-5253-treated cells showed a reduced FITC fluorescence measuring viral attachment (Fig. 2E). Thus, Ro41-5253 primarily decreased the entry step, especially viral attachment. Next, to examine whether Ro41-5253 targeted HBV particles or host cells, HepaRG cells pretreated with compounds were examined for susceptibility to HBV infection in the absence of compounds (Fig. 2F). As a positive control, HBV infection was blocked by pretreatment of cells with an NTCP-binding lipopeptide, preS1(2–48)myr (preS1 peptide) (15), but not by heparin, which binds HBV particles instead (Fig. 2F, 2nd and 3rd lanes) (14). HBV infection was also diminished in HepaRG cells pretreated with IL-1β, which induced an innate immune response (Fig. 2F, 4th lane) (37). In this experiment, Ro41-5253-pretreated HepaRG cells were less susceptible to HBV infection (Fig. 2F, 5th lane), suggesting that the activity of Ro41-5253 in host cells contributed to the inhibition of HBV entry.

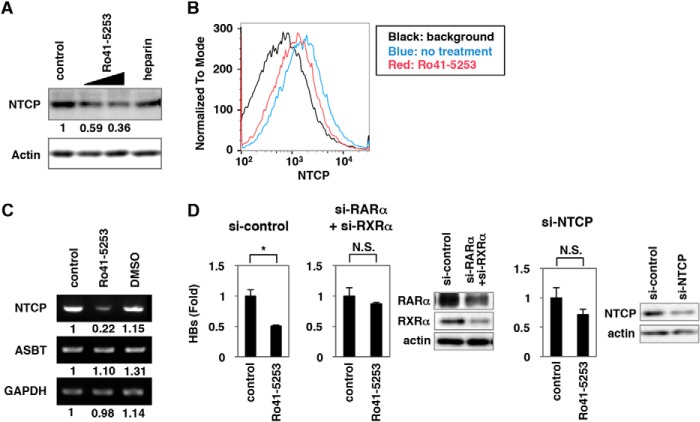

Ro41-5253 Down-regulated NTCP

Next, we examined how treatment of hepatocytes with Ro41-5253 decreased HBV susceptibility. Recently, NTCP was reported to be essential for HBV entry (15). Intriguingly, we found that Ro41-5253 decreased the level of NTCP protein in HepaRG cells (Fig. 3A). Flow cytometry showed that NTCP protein on the cell surface was consistently down-regulated following treatment with Ro41-5253 (Fig. 3B, compare red and blue). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR revealed that mRNA levels for NTCP, but not apical sodium-dependent bile salt transporter (ASBT, also known as NTCP2 or SLC10A2), another SLC10 family transporter, were reduced by Ro41-5253 in HepaRG cells (Fig. 3C). Thus, Ro41-5253 could reduce NTCP expression. When endogenous NTCP and RAR was knocked down by siRNA, the anti-HBV effect of Ro41-5253 was significantly diminished (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the inhibitory activity of Ro41-5253 to HBV infection was, at least in part, mediated by targeting NTCP. These data suggest that Ro41-5253 down-regulated NTCP, which probably contributed to the anti-HBV activity of Ro41-5253.

FIGURE 3.

Ro41-5253 reduced NTCP expression. A, HepaRG cells were treated or untreated with 10 and 20 μm Ro41-5253 or 50 units/ml heparin for 12 h, and the levels of NTCP (upper panel) and actin (lower panel) were examined by Western blot analysis. The relative intensities for the bands of NTCP measured by densitometry are shown below the upper panel. B, flow cytometric determination of NTCP protein level on the cell surface of primary human hepatocytes treated with 20 μm Ro41-5253 (red) for 24 h or left untreated (blue). The black line indicates the background signal corresponding to the cells untreated with the primary antibody. C, RT-PCR determination of the mRNA levels for NTCP (upper panel), ASBT (middle panel), and GAPDH (lower panel) in cells treated with 20 μm Ro41-5253 or 0.1% DMSO for 12 h or left untreated. The relative intensities for the bands measured by densitometry are shown below the panels. D, HepaRG cells were treated with siRNA against RARa (si-RARa) plus that against RXRa (si-RXRa), that against NTCP (si-NTCP), and a randomized siRNA (si-control) for 3 days and then were re-treated with siRNAs for 3 days. The cells were pretreated with or without Ro41-5253 for 24 h and then infected with HBV for 16 h. HBs antigen produced from the infected cells were measured at 12 days postinfection. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t test (*, p < 0.05; NS, not significant).

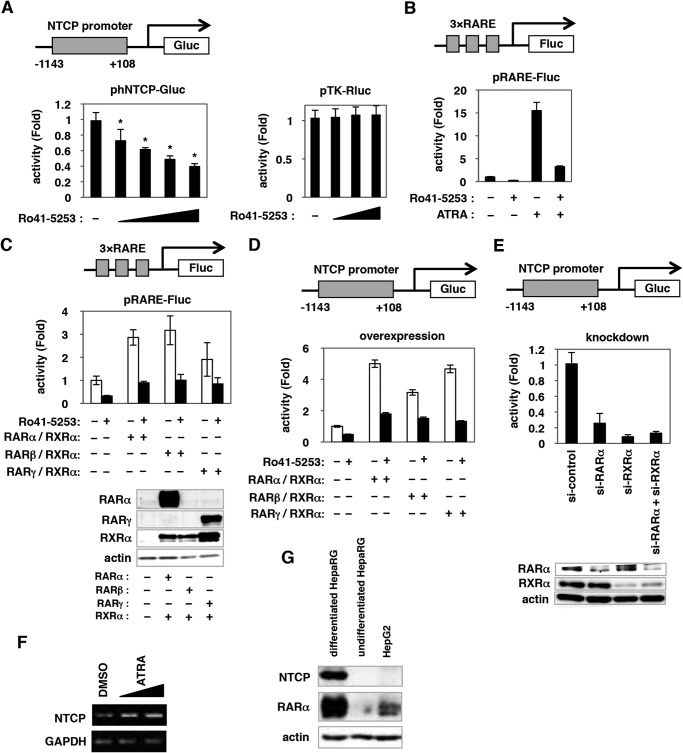

Retinoic Acid Receptor Regulated NTCP Promoter Activity

To determine the mechanism for Ro41-5253-induced down-regulation of NTCP, we used a reporter construct inserting nucleotides (nt) −1143 to +108 of the human NTCP (hNTCP) promoter upstream of the Gluc gene (Fig. 4A, upper panel). Ro41-5253 dose-dependently decreased the luciferase activity driven from this promoter, although the effect was modest and showed up to ∼40% reduction (Fig. 4A, left panel). Ro41-5253 had little effect on the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter (Fig. 4A, right panel), suggesting that Ro41-5253 specifically repressed hNTCP promoter activity. As reported previously (38), Ro41-5253 specifically inhibited RAR-mediated transcription (Fig. 4, B and C). RARα, RARβ, and RARγ are members of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily, which are ligand-activated transcription factors that regulate the transcription of specific downstream genes by binding to the RAR-responsive element (RARE) predominantly in the form of a heterodimer with RXR. We therefore asked whether RAR could regulate the hNTCP promoter. As shown in Fig. 4D, hNTCP promoter activity was stimulated by overexpression of either RARα, RARβ, or RARγ together with RXRα, and transcription augmented by RAR could be repressed by Ro41-5253 (Fig. 4D). Knockdown of endogenous RARα, RXRα, or both dramatically impaired the activity of the hNTCP promoter (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that RAR/RXR is involved in the transcriptional regulation of the hNTCP gene. Consistently, an RAR agonist, ATRA, induced NTCP mRNA expression (Fig. 4F).

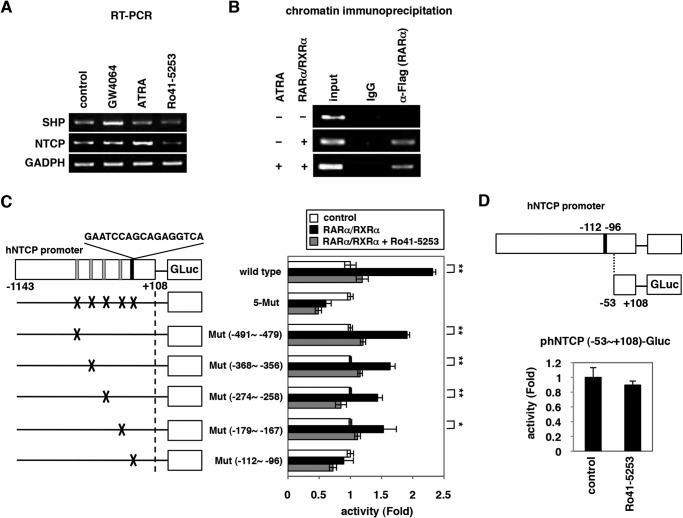

FIGURE 4.

RAR could regulate hNTCP promoter activity. A, left panel, HuS-E/2 cells were transfected for 6 h with an hNTCP reporter construct with −1143/+108 of the hNTCP promoter region cloned upstream of the Gluc gene (upper panel, phNTCP-Gluc), together with an internal control plasmid expressing SEAP (pSEAP). Cells were treated or untreated with various concentrations of Ro41-5253 (5–40 μm) for 48 h. The Gluc and SEAP activities were determined, and the Gluc values normalized by SEAP are shown. Right panel, HuS-E/2 cells transfected with a reporter construct carrying the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter (pTK-Rluc) were examined for luciferase activity in the presence or absence of Ro41-5253 (10–40 μm). B, HuS-E/2 cells transfected with a Fluc-encoding reporter plasmid carrying three tandem repeats of RARE (upper panel, pRARE-Fluc), and Rluc-encoding reporter plasmid driven from herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter (pTK-Rluc) were treated with or without 20 μm Ro41-5253 in the presence or absence of an RAR agonist, ATRA, 1 μm for 24 h. Relative values for Fluc normalized by Rluc are shown. C, HuS-E/2 cells transfected with pRARE-Fluc and pTK-Rluc with or without expression plasmids for RARs (RARα, RARβ, or RARγ) and RXRα were treated with (black) or without (white) Ro41-5253 for 48 h. Relative values for Fluc/Rluc are shown. D, HuS-E/2 cells were cotransfected with phNTCP-Gluc and pSEAP with or without the expression plasmids for RARs (RARα, RARβ, or RARγ) and RXRα, followed by 24 h of treatment or no treatment with 20 μm Ro41-5253. Relative Gluc/SEAP values are shown. E, phNTCP-Gluc and pSEAP were transfected into HuS-E/2 cells together with siRNAs against RARα (si-RARα), RXRα (si-RXRα), si-RARα plus si-RXRα, or randomized siRNA (si-control) for 48 h. Relative Gluc/SEAP values are indicated. Endogenous RARα, RXRα, and actin proteins were detected by Western blot analysis (lower panels). F, mRNA levels for NTCP and GAPDH were detected in differentiated HepaRG cells treated with or without ATRA (0.5 and 1 μm) for 24 h. G, protein levels for endogenous NTCP (upper panel), RARα (middle panel), and actin (lower panel, as an internal control) were determined by Western blot analysis of differentiated HepaRG, undifferentiated HepaRG, and HepG2 cells. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t test (*, p < 0.05).

Importantly, endogenous expression of RARα was more abundant in differentiated HepaRG cells, which are susceptible to HBV infection, than that in undifferentiated HepaRG and HepG2 cells, which are not susceptible (Fig. 4G) (29). This expression pattern was consistent with the expression of NTCP and with HBV susceptibility, suggesting the significance of RAR in regulating NTCP expression.

Promoter Analysis of hNTCP

We next examined whether RAR regulation of the hNTCP promoter is direct or indirect. From the analyses so far using the rat Ntcp (rNtcp) promoter, one of the major regulators for rNtcp expression is farnesoid X receptor (FXR), which is a nuclear receptor recognizing bile acids (39). FXR, which is activated upon intracellular bile acids, indirectly regulates rNtcp expression; FXR induces its downstream small heterodimer partner (Shp), another nuclear receptor, and Shp recruits to the rNtcp promoter to repress the promoter activity (39). Then we examined whether RAR affected the expression of human SHP. As shown in Fig. 5A, although an FXR agonist GW4064 remarkably induced SHP expression as reported (39), RAR did not have a remarkable effect on the SHP level in HepaRG cells (Fig. 5A). To assess the direct involvement of RAR in hNTCP regulation, the ChIP assay showed that RAR was associated with the hNTCP promoter both in the presence and absence of ATRA (Fig. 5B), consistent with the characteristic that RAR/RXR binds to RARE regardless of ligand stimulation (40). The Genomatix software predicts that the hNTCP promoter possesses five putative RAREs in nt −1143 to +108 (Fig. 5C). Introduction of mutations in all of these five elements lost the promoter activation by RAR/RXR overexpression (Fig. 5C, 5-Mut). Although the promoters mutated in the motif nt −491 to −479, −368 to −356, −274 to −258, or −179 to −167 were activated by ectopic expression of RAR/RXR and this activation was cancelled by Ro41-5253 treatment, the hNTCP promoter with mutations in nt −112 to −96 had no significant response by RAR/RXR (Fig. 5C). Promoter activity of hNTCP that lacked the region nt −112 to −96 (nt −53 to +108) was not affected by Ro41-5253 (Fig. 5D). These data suggest that the nt −112 to −96 region is responsible for RAR-mediated transcriptional activation of hNTCP.

FIGURE 5.

RAR directly regulated the activity of hNTCP promoter. A, HepaRG cells were treated with or without ATRA, Ro41-5253, or a positive control GW4064, which is an FXR agonist, for 24 h. mRNAs for SHP as well as NTCP and GAPDH were detected by RT-PCR. B, ChIP assay was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures” with Huh7-25 cells transfected with or without an expression plasmid for FLAG-tagged RARa plus that for RXRa in the presence or absence of ATRA stimulation. C, left panel, schematic representation of hNTCP promoter and the reporter constructs used in this study. hNTCP promoter has five putative RAREs (nt −491 to −479, −368 to −356, −274 to −258, −179 to −167 (gray regions), and −112 to −96 (black regions, GAATCCAGCAGAGGTCA)) in nt −1143 to +108 of hNTCP. The mutant constructs possessing mutations within each putative RAREs and in all of five elements (5-Mut) as well as the wild type construct are shown. Right panel, relative luciferase activities upon overexpression with or without RARa plus RXRa in the presence or absence of Ro41-5253. D, deletion reporter construct carrying the region nt −53 to +108 of the hNTCP upstream of the Gluc gene was used for the reporter assay in the presence or absence of Ro41-5253.

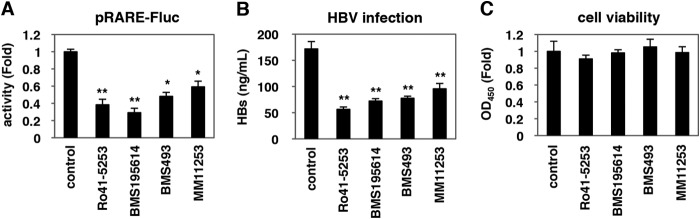

HBV Susceptibility was Decreased in RAR-inactivated Cells

We further investigated the impact of RAR antagonization on HBV infectivity. BMS195614, BMS493, and MM11253, which repressed RAR-mediated transcription (Fig. 6A), all decreased the susceptibility of HepaRG cells to HBV infection (Fig. 6B) without significant cytotoxicity (Fig. 6C). These data confirmed that HBV infection was restricted in RAR-inactivated cells. Among these, CD2665, a synthetic retinoid that is known to inhibit RAR-mediated transcription (Fig. 7A), had more potent anti-HBV activity than Ro41-5253 (Fig. 7B), which was accompanied by the inhibition of the hNTCP promoter (Fig. 7C) and down-regulation of NTCP protein (Fig. 7D).

FIGURE 6.

HBV susceptibility was decreased in RAR-inactivated cells. A, HuS-E/2 cells were transfected with the pRARE-Fluc and pTK-Rluc for 6 h followed by treatment with or without the indicated compounds at 20 μm for 48 h. Relative Fluc values normalized by Rluc are shown. B and C, HepaRG cells treated with or without the indicated compounds 20 μm were subjected to the HBV infection assay according to the scheme in Fig. 1A. HBs antigen in the culture supernatant was determined by ELISA (B). Cell viability was also quantified by MTT assay (C). Statistical significance was determined using Student's t test (*, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01).

FIGURE 7.

CD2665 had a stronger anti-HBV activity than Ro41-5253. A, chemical structure of CD2665. B, HepaRG cells treated with or without 1 μm preS1 peptide, 0.1% DMSO, or various concentrations of Ro41-5253 or CD2665 (5, 10, and 20 μm) were subjected to HBV infection according to the protocol shown in Fig. 1A. HBV infection was detected by quantifying the HBs secretion into the culture supernatant by ELISA. The efficiency of HBV infection was monitored by ELISA detection of secreted HBs. C, HuS-E/2 cells transfected with phNTCP-Gluc and pSEAP were treated with the indicated compounds at 20 μm for 24 h. Relative Gluc/SEAP values are shown. D, NTCP (upper panel) and actin proteins as an internal control (lower panel) were examined by Western blot analysis of HepaRG cells treated with or without the indicated compounds at 20 μm. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t test (**, p < 0.01).

CD2665 Showed a Pan-genotypic Anti-HBV Effect

We then examined the effect of CD2665 on the infection of primary human hepatocytes with different HBV genotypes. CD2665 significantly reduced the infection of HBV genotypes A, B, C, and D, as revealed by quantification of HBs and HBe antigens in the culture supernatant of infected cells (Fig. 8, A–D). Additionally, this RAR inhibitor decreased the infection of the ETV- and LMV-resistant HBV genotype C clone carrying mutations in L180M, S202G, and M204V (Fig. 8, E and F). Thus, CD2665 showed pan-genotypic anti-HBV effects and was also effective on an HBV isolate with resistance to nucleoside analogs.

We further investigated whether RAR inhibitors could prevent HBV spread. It was recently reported that HBV infection in freshly isolated primary human hepatocytes could spread during long term culture through production of infectious virions and reinfection of surrounding cells (41). As shown in Fig. 8G, the percentage of HBV-positive cells increased up to 30 days postinfection without compound treatment (Fig. 8G, panels a–d). However, such HBV spread was clearly interrupted by treatment with Ro41-5253 and CD2665 as well as preS1 peptide (Fig. 8G, panels e–p). The rise of HBs antigen in the culture supernatant along with the culture time up to 30 days was remarkably inhibited by continuous treatment with Ro41-5253 and CD2665 as well as preS1 peptide without serious cytotoxicity (Fig. 8G, right graph). Thus, continuous RAR inactivation could inhibit the spread of HBV by interrupting de novo infection.

DISCUSSION

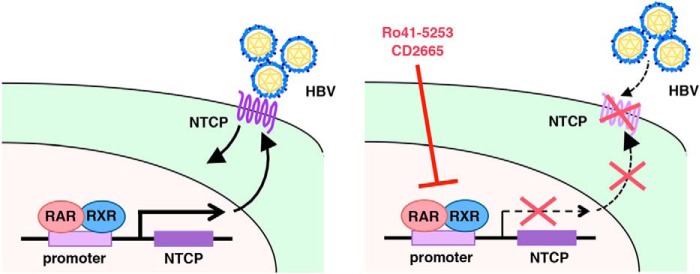

In this study, we screened a chemical library using a HepaRG-based HBV infection system and found that pretreatment with Ro41-5253 decreased HBV infection by blocking viral entry. HBV entry follows multiple steps starting with low affinity viral attachment to the cell surface followed by specific binding to entry receptor(s), including NTCP. NTCP is reported to be essential for HBV entry (42). So far, we and other groups have reported that NTCP-binding agents, including cyclosporin A and its derivatives, as well as bile acids, including ursodeoxycholic acid and taurocholic acid, inhibited HBV entry by interrupting the interaction between NTCP and HBV large surface protein (19, 35). Ro41-5253 was distinct from these agents and was found to decrease host susceptibility to HBV infection by modulating the expression levels of NTCP. These results suggest that the regulatory circuit for NTCP expression is one of the determinants for susceptibility to HBV infection. We previously showed that the cell surface NTCP protein expression correlated with susceptibility to HBV infection (43). We therefore screened for compounds inhibiting hNTCP promoter activity to identify HBV entry inhibitors (data not shown) (44). Intriguingly, all of the compounds identified as repressors of the hNTCP promoter were inhibitors of RAR-mediated transcription. This strongly suggests that RAR plays a crucial role in regulating the activity of the hNTCP promoter (Fig. 9). We consistently found that RAR was abundantly expressed in differentiated HepaRG cells susceptible to HBV infection, in contrast to the low expression of RAR in undifferentiated HepaRG and HepG2 cells, which were not susceptible to HBV (Fig. 4G). RARE is also found in the HBV enhancer I region (45). RAR is likely to have multiple roles in regulating the HBV life cycle.

FIGURE 9.

Schematic representation of the mechanism for RAR involvement in the regulation of NTCP expression and HBV infection. Left panel, RAR/RXR recruits to the promoter region of NTCP and regulates the transcription. The expression of NTCP in the plasma membrane supports HBV infection. Right panel, RAR antagonists, including Ro41-5253 and CD2665, repress the transcription of NTCP via RAR antagonization, which decreases the expression level of NTCP in the plasma membrane and abolishes the entry of HBV into host cells.

So far, only transcriptional regulation of rat Ntcp has been extensively analyzed (39, 46, 47). However, the transcription of hNTCP was shown to be differently regulated mainly because of sequence divergence in the promoter region (48), and transcriptional regulation of hNTCP remains poorly understood. Hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF)1α and HNF4α, which positively regulated the rat Ntcp promoter, had little effect on hNTCP promoter activity (48). HNF3β bound to the promoter region and inhibited promoter activities of both hNTCP and rat Ntcp. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein also bound and regulated the hNTCP promoter (44, 48). A previous study, which was mainly based on reporter assays using a construct of the region from −188 to +83 of the hNTCP promoter, concluded that RAR did not affect hNTCP transcription (48). By using a reporter carrying a longer promoter region, our study is the first to implicate RARs in the regulation of hNTCP gene expression (Fig. 9). The turnover of NTCP protein was reported to be rapid, with a half-life of much less than 24 h (49). Consequently, reduction in the NTCP transcription by RAR inhibition could rapidly decrease the NTCP protein level and affect HBV susceptibility.

NTCP plays a major role in the hepatic influx of conjugated bile salts from portal circulation. Because NTCP knock-out mice are so far unavailable, it is not known whether loss of NTCP function can cause any physiological defect in vivo. However, no serious diseases are reported in individuals carrying single nucleotide polymorphisms that significantly decrease the transporter activity of NTCP (50, 51), suggesting that NTCP function may be redundant with other proteins. Organic anion transporting polypeptides are also known to be involved in bile acid transport. Moreover, an inhibition assay using Myrcludex-B showed that the IC50 value for HBV infection was ∼0.1 nm (52), although that for NTCP transporter function was 4 nm (28), suggesting that HBV infection could be inhibited without fully inactivating the NTCP transporter (53). HBV entry inhibitors are expected to be useful for preventing de novo infection upon post-exposure prophylaxis or vertical transmission where serious toxicity might be avoided with a short term treatment (54). For drug development studies against HIV, down-regulation of the HIV coreceptor CCR5 by ribozymes could inhibit HIV infection both in vitro and in vivo (55). Disruption of CCR5 by zinc finger nucleases could reduce permissiveness to HIV infection and was effective in decreasing viral load in vivo (56). Thus, interventions to regulate viral permissiveness could become a method for eliminating viral infection (55). Our findings suggest that the regulatory mechanisms of NTCP expression could serve as targets for the development of anti-HBV agents. High throughput screening with a reporter assay using an NTCP promoter-driven reporter, as exemplified by this study, will be useful for identifying more anti-HBV drugs.

Acknowledgments

HepAD38 and HuS-E/2 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Christoph Seeger at Fox Chase Cancer Center and Dr. Kunitada Shimotohno at National Center for Global Health and Medicine. We are also grateful to all of the members of Department of Virology II, National Institute of Infectious Diseases.

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan, from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan, and from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and by the incentive support from Liver Forum in Kyoto.

- HBV

- hepatitis B virus

- NTCP

- sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide

- RAR

- retinoic acid receptor

- LMV

- lamivudine

- ETV

- entecavir

- HB

- HBV surface protein

- SLC10A1

- solute carrier protein 10A1

- hNTCP

- human NTCP

- ATRA

- all-trans-retinoic acid

- SHP

- small heterodimer partner

- ASBT

- apical sodium-dependent bile salt transporter

- RARE

- RAR-responsive element

- RXR

- retinoid X receptor

- SEAP

- secreted alkaline phosphatase

- FXR

- farnesoid X receptor

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- nt

- nucleotide

- cccDNA

- covalently closed circular DNA.

REFERENCES

- 1. Liang T. J. (2009) Hepatitis B: the virus and disease. Hepatology 49, S13–S21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ott J. J., Stevens G. A., Groeger J., Wiersma S. T. (2012) Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine 30, 2212–2219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zoulim F., Locarnini S. (2013) Optimal management of chronic hepatitis B patients with treatment failure and antiviral drug resistance. Liver Int. 33, Suppl. 1, 116–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arbuthnot P., Kew M. (2001) Hepatitis B virus and hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 82, 77–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kao J. H., Chen P. J., Chen D. S. (2010) Recent advances in the research of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiologic and molecular biological aspects. Adv. Cancer Res. 108, 21–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lok A. S. (2002) Chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 1682–1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pagliaccetti N. E., Chu E. N., Bolen C. R., Kleinstein S. H., Robek M. D. (2010) λ and α interferons inhibit hepatitis B virus replication through a common molecular mechanism but with different in vivo activities. Virology 401, 197–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robek M. D., Boyd B. S., Chisari F. V. (2005) λ interferon inhibits hepatitis B and C virus replication. J. Virol. 79, 3851–3854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dusheiko G. (2013) Treatment of HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B: interferon or nucleoside analogues. Liver Int. 33, 137–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lau G. K., Piratvisuth T., Luo K. X., Marcellin P., Thongsawat S., Cooksley G., Gane E., Fried M. W., Chow W. C., Paik S. W., Chang W. Y., Berg T., Flisiak R., McCloud P., Pluck N., and Peginterferon Alfa-2a HBeAg-Positive Chronic Hepatitis B Study Group. (2005) Peginterferon Alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 2682–2695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen L. P., Zhao J., Du Y., Han Y. F., Su T., Zhang H. W., Cao G. W. (2012) Antiviral treatment to prevent chronic hepatitis B or C-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Virol. 1, 174–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ohishi W., Chayama K. (2012) Treatment of chronic hepatitis B with nucleos(t)ide analogues. Hepatol. Res. 42, 219–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu F., Wang X., Wei F., Hu H., Zhang D., Hu P., Ren H. (2014) Efficacy and resistance in de novo combination lamivudine and adefovir dipivoxil therapy versus entecavir monotherapy for the treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B: a meta-analysis. Virol. J. 11, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schulze A., Gripon P., Urban S. (2007) Hepatitis B virus infection initiates with a large surface protein-dependent binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Hepatology 46, 1759–1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yan H., Zhong G., Xu G., He W., Jing Z., Gao Z., Huang Y., Qi Y., Peng B., Wang H., Fu L., Song M., Chen P., Gao W., Ren B., Sun Y., Cai T., Feng X., Sui J., Li W. (2012) Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. Elife 1, e00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stieger B. (2011) The role of the sodium-taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) and of the bile salt export pump (BSEP) in physiology and pathophysiology of bile formation. Handb Exp. Pharmacol. 201, 205–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kotani N., Maeda K., Debori Y., Camus S., Li R., Chesne C., Sugiyama Y. (2012) Expression and transport function of drug uptake transporters in differentiated HepaRG cells. Mol. Pharm. 9, 3434–3441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kullak-Ublick G. A., Beuers U., Paumgartner G. (1996) Molecular and functional characterization of bile acid transport in human hepatoblastoma HepG2 cells. Hepatology 23, 1053–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Watashi K., Sluder A., Daito T., Matsunaga S., Ryo A., Nagamori S., Iwamoto M., Nakajima S., Tsukuda S., Borroto-Esoda K., Sugiyama M., Tanaka Y., Kanai Y., Kusuhara H., Mizokami M., Wakita T. (2014) Cyclosporin A and its analogs inhibit hepatitis B virus entry into cultured hepatocytes through targeting a membrane transporter, sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP). Hepatology 59, 1726–1737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gripon P., Cannie I., Urban S. (2005) Efficient inhibition of hepatitis B virus infection by acylated peptides derived from the large viral surface protein. J. Virol. 79, 1613–1622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Petersen J., Dandri M., Mier W., Lütgehetmann M., Volz T., von Weizsäcker F., Haberkorn U., Fischer L., Pollok J. M., Erbes B., Seitz S., Urban S. (2008) Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in vivo by entry inhibitors derived from the large envelope protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 335–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ladner S. K., Otto M. J., Barker C. S., Zaifert K., Wang G. H., Guo J. T., Seeger C., King R. W. (1997) Inducible expression of human hepatitis B virus (HBV) in stably transfected hepatoblastoma cells: a novel system for screening potential inhibitors of HBV replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41, 1715–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aly H. H., Watashi K., Hijikata M., Kaneko H., Takada Y., Egawa H., Uemoto S., Shimotohno K. (2007) Serum-derived hepatitis C virus infectivity in interferon regulatory factor-7-suppressed human primary hepatocytes. J. Hepatol. 46, 26–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sugiyama M., Tanaka Y., Kato T., Orito E., Ito K., Acharya S. K., Gish R. G., Kramvis A., Shimada T., Izumi N., Kaito M., Miyakawa Y., Mizokami M. (2006) Influence of hepatitis B virus genotypes on the intra- and extracellular expression of viral DNA and antigens. Hepatology 44, 915–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Watashi K., Hijikata M., Tagawa A., Doi T., Marusawa H., Shimotohno K. (2003) Modulation of retinoid signaling by a cytoplasmic viral protein via sequestration of Sp110b, a potent transcriptional corepressor of retinoic acid receptor, from the nucleus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 7498–7509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marusawa H., Hijikata M., Watashi K., Chiba T., Shimotohno K. (2001) Regulation of Fas-mediated apoptosis by NF-κB activity in human hepatocyte derived cell lines. Microbiol. Immunol. 45, 483–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Watashi K., Khan M., Yedavalli V. R., Yeung M. L., Strebel K., Jeang K. T. (2008) Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication and regulation of APOBEC3G by peptidyl prolyl isomerase Pin1. J. Virol. 82, 9928–9936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ni Y., Lempp F. A., Mehrle S., Nkongolo S., Kaufman C., Fälth M., Stindt J., Königer C., Nassal M., Kubitz R., Sültmann H., Urban S. (2014) Hepatitis B and D viruses exploit sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide for species-specific entry into hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 146, 1070–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gripon P., Rumin S., Urban S., Le Seyec J., Glaise D., Cannie I., Guyomard C., Lucas J., Trepo C., Guguen-Guillouzo C. (2002) Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 15655–15660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cattaneo R., Will H., Schaller H. (1984) Hepatitis B virus transcription in the infected liver. EMBO J. 3, 2191–2196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hirsch R. C., Lavine J. E., Chang L. J., Varmus H. E., Ganem D. (1990) Polymerase gene products of hepatitis B viruses are required for genomic RNA packaging as well as for reverse transcription. Nature 344, 552–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huan B., Siddiqui A. (1993) Regulation of hepatitis B virus gene expression. J. Hepatol. 17, S20–S23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Newman M., Suk F. M., Cajimat M., Chua P. K., Shih C. (2003) Stability and morphology comparisons of self-assembled virus-like particles from wild-type and mutant human hepatitis B virus capsid proteins. J. Virol. 77, 12950–12960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yeh C. T., Ou J. H. (1991) Phosphorylation of hepatitis B virus precore and core proteins. J. Virol. 65, 2327–2331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nkongolo S., Ni Y., Lempp F. A., Kaufman C., Lindner T., Esser-Nobis K., Lohmann V., Mier W., Mehrle S., Urban S. (2014) Cyclosporin A inhibits hepatitis B and hepatitis D virus entry by cyclophilin-independent interference with the NTCP receptor. J. Hepatol. 65, 723–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sells M. A., Zelent A. Z., Shvartsman M., Acs G. (1988) Replicative intermediates of hepatitis B virus in HepG2 cells that produce infectious virions. J. Virol. 62, 2836–2844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Watashi K., Liang G., Iwamoto M., Marusawa H., Uchida N., Daito T., Kitamura K., Muramatsu M., Ohashi H., Kiyohara T., Suzuki R., Li J., Tong S., Tanaka Y., Murata K., Aizaki H., Wakita T. (2013) Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α trigger restriction of hepatitis B virus infection via a cytidine deaminase activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 31715–31727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Apfel C., Bauer F., Crettaz M., Forni L., Kamber M., Kaufmann F., LeMotte P., Pirson W., Klaus M. (1992) A retinoic acid receptor α antagonist selectively counteracts retinoic acid effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 7129–7133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Denson L. A., Sturm E., Echevarria W., Zimmerman T. L., Makishima M., Mangelsdorf D. J., Karpen S. J. (2001) The orphan nuclear receptor, shp, mediates bile acid-induced inhibition of the rat bile acid transporter, ntcp. Gastroenterology 121, 140–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bastien J., Rochette-Egly C. (2004) Nuclear retinoid receptors and the transcription of retinoid-target genes. Gene 328, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ishida Y., Yamasaki C., Yanagi A., Yoshizane Y., Chayama K., Tateno C. (2013) International Meeting on Molecular Biology of Hepatitis B Virus P13 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yan H., Peng B., Liu Y., Xu G., He W., Ren B., Jing Z., Sui J., Li W. (2014) Viral entry of hepatitis B and D viruses and bile salts transportation share common molecular determinants on sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide. J. Virol. 88, 3273–3284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Iwamoto M., Watashi K., Tsukuda S., Aly H. H., Fukasawa M., Fujimoto A., Suzuki R., Aizaki H., Ito T., Koiwai O., Kusuhara H., Wakita T. (2014) Evaluation and identification of hepatitis B virus entry inhibitors using HepG2 cells overexpressing a membrane transporter NTCP. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 443, 808–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shiao T., Iwahashi M., Fortune J., Quattrochi L., Bowman S., Wick M., Qadri I., Simon F. R. (2000) Structural and functional characterization of liver cell-specific activity of the human sodium/taurocholate cotransporter. Genomics 69, 203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huan B., Siddiqui A. (1992) Retinoid X receptor RXRα binds to and trans-activates the hepatitis B virus enhancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 9059–9063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Geier A., Martin I. V., Dietrich C. G., Balasubramaniyan N., Strauch S., Suchy F. J., Gartung C., Trautwein C., Ananthanarayanan M. (2008) Hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α is a central transactivator of the mouse Ntcp gene. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 295, G226–G233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zollner G., Wagner M., Fickert P., Geier A., Fuchsbichler A., Silbert D., Gumhold J., Zatloukal K., Kaser A., Tilg H., Denk H., Trauner M. (2005) Role of nuclear receptors and hepatocyte-enriched transcription factors for Ntcp repression in biliary obstruction in mouse liver. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 289, G798–G805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jung D., Hagenbuch B., Fried M., Meier P. J., Kullak-Ublick G. A. (2004) Role of liver-enriched transcription factors and nuclear receptors in regulating the human, mouse, and rat NTCP gene. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 286, G752–G761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rippin S. J., Hagenbuch B., Meier P. J., Stieger B. (2001) Cholestatic expression pattern of sinusoidal and canalicular organic anion transport systems in primary cultured rat hepatocytes. Hepatology 33, 776–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ho R. H., Leake B. F., Roberts R. L., Lee W., Kim R. B. (2004) Ethnicity-dependent polymorphism in Na+-taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (SLC10A1) reveals a domain critical for bile acid substrate recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7213–7222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pan W., Song I. S., Shin H. J., Kim M. H., Choi Y. L., Lim S. J., Kim W. Y., Lee S. S., Shin J. G. (2011) Genetic polymorphisms in Na+-taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP) and ileal apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT) and ethnic comparisons of functional variants of NTCP among Asian populations. Xenobiotica 41, 501–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schulze A., Schieck A., Ni Y., Mier W., Urban S. (2010) Fine mapping of pre-S sequence requirements for hepatitis B virus large envelope protein-mediated receptor interaction. J. Virol. 84, 1989–2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Watashi K., Urban S., Li W., Wakita T. (2014) NTCP and beyond: opening the door to unveil hepatitis B virus entry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 2892–2905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Deuffic-Burban S., Delarocque-Astagneau E., Abiteboul D., Bouvet E., Yazdanpanah Y. (2011) Blood-borne viruses in health care workers: prevention and management. J. Clin. Virol. 52, 4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bai J., Gorantla S., Banda N., Cagnon L., Rossi J., Akkina R. (2000) Characterization of anti-CCR5 ribozyme-transduced CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells in vitro and in a SCID-hu mouse model in vivo. Mol. Ther. 1, 244–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Perez E. E., Wang J., Miller J. C., Jouvenot Y., Kim K. A., Liu O., Wang N., Lee G., Bartsevich V. V., Lee Y. L., Guschin D. Y., Rupniewski I., Waite A. J., Carpenito C., Carroll R. G., Orange J. S., Urnov F. D., Rebar E. J., Ando D., Gregory P. D., Riley J. L., Holmes M. C., June C. H. (2008) Establishment of HIV-1 resistance in CD4+ T cells by genome editing using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 808–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]