Abstract

Bcr-Abl kinase is known to reverse apoptosis of cytokine-dependent cells due to cytokine deprivation, although it has been controversial whether chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) progenitors have the potential to survive under conditions in which there are limited amounts of cytokines. Here we demonstrate that early hematopoietic progenitors (Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin−) isolated from normal mice rapidly undergo apoptosis in the absence of cytokines. In these cells, the expression of Bim, a proapoptotic relative of Bcl-2 which plays a key role in the cytokine-mediated survival system, is induced. In contrast, those cells isolated from our previously established CML model mice resist apoptosis in cytokine-free medium without the induction of Bim expression, and these effects are reversed by the Abl-specific kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate. In addition, the expression levels of Bim are uniformly low in cell lines established from patients in the blast crisis phase of CML, and imatinib induced Bim in these cells. Moreover, small interfering RNA that reduces the expression level of Bim effectively rescues CML cells from apoptosis caused by imatinib. These findings suggest that Bim plays an important role in the apoptosis of early hematopoietic progenitors and that Bcr-Abl supports cell survival in part through downregulation of this cell death activator.

In the chronic phase, chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is characterized by massive proliferation of granulocytes in the peripheral blood and their progenitors in the bone marrow. Abnormal hematopoietic stem cells harboring the Bcr-Abl chimeric gene still differentiate into mature granulocytes with apparently normal function but gradually come to occupy the hematopoietic space. They subvert the system controlling their homeostasis in the body and thus accumulate in large numbers. Because cytokines are considered to play critical roles in this homeostasis, dysregulation of cytokine-mediated cell death, cell survival, or cell division by Bcr-Abl may be responsible for leukemogenesis. Indeed, among multiple systems regulating diverse cell functions, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, which are dysregulated by Bcr-Abl, the reversal of apoptosis caused by cytokine deprivation is one of the most consistently observed effects (reviewed in references 15 and 23). This finding has been repeatedly demonstrated by use of different experimental systems that include murine interleukin-3 (IL-3)-dependent Baf-3 and 32D cells (8, 9, 11, 22, 28, 32, 37, 39).

We and others have investigated this cytokine-dependent cell survival system in hematopoietic progenitors by using IL-3-dependent cells and demonstrated that two distinct signaling pathways support cell survival. One pathway emanates from the membrane-proximal region of the common receptor chain (βc chain) shared by IL-3 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, which activates JAK-STAT pathways and transcriptionally upregulates Bcl-xL expression (14, 45, 46). The other pathway functions via the distal portion of the βc chain and activates Ras pathways (26, 27, 30). Because experiments using Baf-3 cells expressing truncated forms of the βc chain revealed that signals from its proximal portion support cell survival only transiently, signals from its distal region, especially the activation of Ras pathways, were considered to be indispensable for long-term cell survival supported by cytokines (26; also reviewed in reference 35).

Recent progress has revealed that cell death decisions are implemented through an evolutionarily conserved mechanism (or general apoptosis program) in which members of the Bcl-2 superfamily play the central roles (reviewed in references 1 and 7). The anti- or proapoptotic family members regulate the translocation of cytochrome c from mitochondria to the cytosol, an event that ultimately activates the caspase cascade, while members of the BH3-only subfamily of cell death activators inhibit the function of the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members by binding to them. In mammals, more than three factors have been identified to be members of each subfamily. Redundancy in each category of the Bcl-2 superfamily has been explained, at least partially, by the tissue- and/or stimulus-specific response of each family member. We therefore concentrated on identifying the major Bcl-2 superfamily member that is regulated by signals from the distal portion of the βc chain, especially via Ras pathways. We and others have found that mRNA and protein expression levels of Bim, a member of the BH3-only death activator subfamily, are downregulated by IL-3 through either the Ras/Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) or the Ras/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) pathway in Baf-3 cells (13, 44). Bim was isolated independently by two groups that exploited its ability to bind Bcl-2 or Mcl1 (20, 36). Alternative splicing gives rise to three variants, BimEL, BimL, and BimS, each of which contains the BH3 domain and functions as a death inducer. It was shown that Bim was induced in Baf-3 cells by IL-3 deprivation but not by other apoptotic triggers, such as DNA damage or Fas, and that enforced expression (but not overexpression) of each form of Bim induced apoptosis in Baf-3 cells even in the presence of IL-3 (44). In addition to Bim induction in hematopoietic cells, the induction of Bim by deprivation of nerve growth factor (NGF) in primary cultures of rat sympathetic neurons, as well as in neuronally differentiated rat pheochromocytoma PC-12 cells, has been reported (5, 40, 49). These findings suggest that the level of Bim expression is a major determinant of cell fate regulated by cytokines.

In addition to its role as a key intracellular factor for cytokine-mediated cell survival, Bim was demonstrated to be an essential regulator of the total number of white blood cells by analysis of Bim-deficient mice (6). Bim-deficient mice have increased numbers of mature monocytes, granulocytes, and lymphocytes but not erythrocytes in the peripheral blood, with overgrowth of hematopoietic precursors in the bone marrow. This prompted us to investigate the roles of Bim as a possible downstream target of Bcr-Abl by using our previously established transgenic (tg) mice in addition to the conventional experimental systems for CML, such as cell lines established from patients in the blast crisis (BC) phase and cytokine-dependent cells expressing Bcr-Abl. In these tg mice, Bcr-Abl is expressed under the control of the tec tyrosine kinase promoter that is active in immature myeloid progenitors (16, 17, 33). Virtually all of these mice develop CML-like disease, namely, proliferation of mature myeloid precursors and megakaryocytes in the bone marrow with increased granulocytes and platelets in the peripheral blood and progressive anemia, within 8 months of birth. They generally die of the disease within 15 months (18). Moreover, when they are intercrossed with p53 haplo-deficient mice, they develop T-cell leukemia and lack functional p53 (19), indicating that this model mimics human CML in both the chronic and BC phases. Here we show that Bim plays an important role in the apoptosis of early hematopoietic progenitors and that Bcr-Abl supports cell survival in part through the downregulation of this cell death activator.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

p210bcr/abl tg (BCR-ABLtg/−) mice were previously described (18). Because the founder mice were generated by using ova derived from (C57BL × DBA)F2 (BDF2) mice and the tg progeny were generated by intercrossing the tg mice with BDF1 mice, the genetic background of the BCR-ABLtg/− mice was a mixture of C57BL/6 and DBA. We used the normal littermates of these mice (BCR-ABL−/−) as controls in this study.

Primary culture and isolation of cytokine-dependent hematopoietic progenitors.

Mice that were 8 to 12 weeks of age were sacrificed, and bone marrow cells were harvested by a standard procedure. Cells were cultured for 5 days in serum-free medium (SF-O2; Sanko Junyaku, Tokyo, Japan) containing 10 ng of thrombopoietin (TPO) per ml and 50 ng of stem cell factor (SCF) per ml. After Ficoll gradient centrifugation to separate dead cells and mature granulocytes, cells expressing lineage-specific markers (CD4, CD8, CD11b, CD41, or Gr-1) were eliminated by using magnetic beads conjugated with specific antibodies (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). More than 90% of lineage marker-negative (Lin−) cells obtained by this procedure were positive for c-Kit. These cells were further divided into Sca-1-enriched (Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin−) and Sca-1-depleted (Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin−) fractions by using magnetic beads conjugated with Sca-1 antibody. Viable cell counts were determined by trypan blue dye exclusion in triplicate assays. Morphology was determined by using cytospin preparations stained with May-Giemsa solution.

TUNEL analysis.

Cells in the Sca-1-enriched fraction were cultured in cytokine-free medium for different periods. Cells were harvested and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and a terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed with an apoptosis detection kit according to the manufacturer's directions (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Cells were then stained with 1 μg of propidium iodide per ml. Cytospin preparations were made, and the incorporation of dUTP was analyzed with a laser cytoscan (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR.

Total cellular RNA was isolated with an Isogen kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan). RNA was reverse transcribed with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Real-time PCR was carried out with an ABI 7700 instrument and SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany), which allows real-time monitoring of the increase in PCR product concentration after every cycle based on the fluorescence of the double-stranded-DNA-specific dye SYBR green. The number of cycles required to produce a product detectable above background levels was measured for each sample and used to calculate differences (n-fold) in starting mRNA levels for each sample. Because we had observed that levels of β-actin and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) mRNA, which are generally used for monitoring equal loading of RNA, were rapidly downregulated in the course of apoptosis by cytokine deprivation in murine IL-3-dependent cell lines (data not shown), we used 28S rRNA as an internal control. The gene primers, selected to cross introns, are listed in Table 1. The real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR products were resolved on a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide to confirm that only single bands of the predicted size were visible.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study for real-time quantitative RT-PCR

| Gene product | Product size (bp) | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 168 | GGGAAGATGGCTGAGTCTGAGCTCATG | TGACTTCAGATTCTTTTCAACTTC |

| Bad | 233 | CCACCAACAGCTATCATGGAGGCGC | GCTCTTTGGGCGAGGAAGTCCCTTG |

| Bax | 162 | AATATGGAGCTGCAGAGGATGATTG | GCACTTTAGTGCACAGGGCCTTGAG |

| Bcl-2 | 261 | GTGGTGGAGGAACTCTTCAGGGATG | GGTCTTCAGAGACAGCCAGGAGAAATC |

| Bcl-xL | 293 | GTAGTGAATGAACTCTTTCGGGATGG | ACCAGCCACAGTCATGCCCGTCAGG |

| BimEL | 324 | AGTGGGTATTTCTCTTTTGACACAG | TCAATGCCTTCTCCATACCAGACG |

| Bim(si) | 119 | AATGTCTGACTCTGACTCTCGGAC | TCTCCGCAGGCTGCAATTGTCTAC |

| Mcl-1 | 259 | GTAATGGTCCATGTTTTCAAAGATG | AAGCCAGCAGCACATTTCTGATGCC |

| DP5/Hrk | 189 | AGACCCAGCCCGGACCGAGCAA | AATAGCACTGGGGTGGCTCT |

| 28S rRNA | 324 | ACGCAGGTGTCCTAAGGCGAGCTC | CACGACGGTCTAAACCCAGCTCAC |

RNA interference.

K562 cells were cultured in medium containing 1 μM imatinib for 24 h. Cells (2 × 106) were then transfected with 5 μg of double-stranded Cy3-labeled Bim small interfering RNA (siRNA) or control siRNA by using a hemagglutinating virus of Japan (HVJ) envelope (GenomeONE; Ishihara Sangyo Kaisha, Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer's directions. Cell culture was continued in the presence of imatinib for 24 h, and then cells were harvested to isolate RNA and cell lysate. Cells were also stained with annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Promega), followed by analysis with flow cytometry. The primers used were the following, according to Reginato et al. (42): control sense, 5′-(GGCUGUAACUUACGUGUACUU)d(TT)-3′; control antisense, 5′-(AAGUACACGUAAGUUACAGCC)d(TT)-3′; Bim sense, 5′-(GACCGAGAAGGUAGACAAUUG)d(TT)-3′; Bim antisense, 5′-(CAAUUGUCUACCUUCUCGGUC)d(TT)-3′.

Immunoblot analysis.

Cells were solubilized in Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Nonidet P-40, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0]) containing protease inhibitor mixture (Complete; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany); total cellular proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Cell lysates extracted from 105 living cells for hematopoietic progenitors isolated from primary culture or 106 living cells for Baf-3 or cell lines established from patients with leukemia were applied to each lane. After their wet electrotransfer onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, the proteins were detected with the appropriate antibodies by following standard procedures. The blots were then stained with primary antibodies followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin secondary antibodies and subjected to chemiluminescence detection according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Bim-specific polyclonal antibodies were raised against glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins containing amino acids 9 to 53 of mouse BimL, as previously described (44). Bcl-2 and Bcl-x polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, Ky.), a monoclonal antibody against β-actin was purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, Calif.), and polyclonal antibodies against total and phosphorylated-specific Akt and MAPK were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, Mass.).

Experiments using Baf-3 cells.

Murine IL-3-dependent cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 20 mM HEPES, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5% conditioned medium of 10T1/2 cells as a source of murine IL-3. To deplete IL-3, we washed the cells twice with IL-3-free growth medium. Cell lines established from patients with leukemia were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Cell viability was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion. For retrovirus-mediated gene expression, we constructed a control CD8-expressing vector plasmid (pMX/IRES-CD8) from the pMX retroviral vector (a gift of T. Kitamura) (38) by inserting an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)-CD8 cassette in which the mouse CD8 cDNA was fused in frame to the IRES sequence. The Bcr-Abl gene was expressed by inserting the cDNA immediately after the 5′ long terminal repeat sequence. The retrovirus was made by the method described by Onishi et al. (38), using BOSC23 cells. Retroviral infection of Baf-3 cells and the selection of CD8-positive cells with a CD8 monoclonal antibody and MACS separation columns (Miltenyi Biotec) were performed according to a method described previously (27). The selection procedure was repeated until more than 95% of the cells were positive for CD8 by flow cytometry.

Reagents and statistical analysis.

A MAPK inhibitor, PD98059 (PD), and a PI3-K inhibitor, LY294002 (LY), were purchased from Wako Pure Chemicals and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo.), respectively. The 2-phenylaminopyrimidine derivative imatinib mesylate was a kind gift of Elisabeth Buchdunger (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland). An analysis of variance and the post hoc method were used to compare viable cell counts in different culture conditions. Significant differences were defined as having a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Amplification and isolation of hematopoietic progenitors from mouse bone marrow.

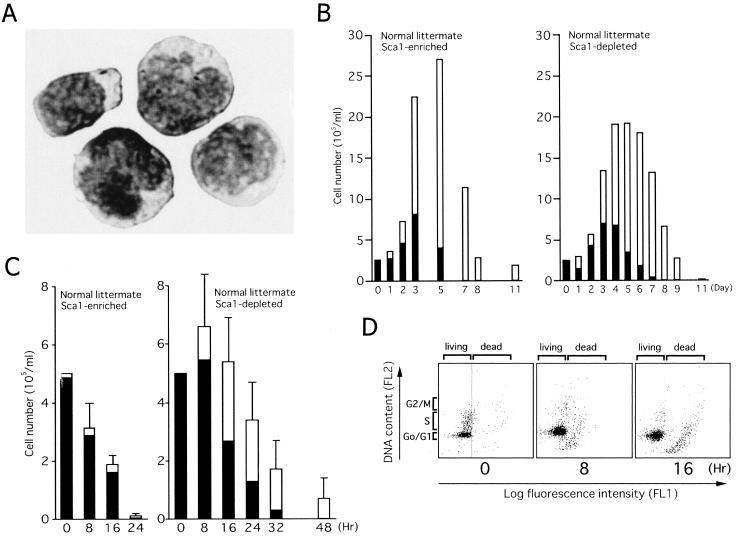

We initially tested the role of Bim in the regulation of cell survival by using cytokine-dependent undifferentiated hematopoietic progenitors isolated from primary cultures of bone marrow cells from normal mice. Cells from normal littermates of the Bcr-Abl tg mice (18) were cultured for 5 days in serum-free medium containing 10 ng of TPO per ml and 50 ng of SCF per ml. After the elimination of dead cells, mature granulocytes, and cells expressing lineage-specific markers (CD4, CD8, CD11b, CD41, or Gr-1), more than 90% of the cells were negative for lineage markers and positive for c-Kit (c-Kit+ Lin−). These cells were further divided into Sca-1-enriched fractions (Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin−; typically more than 75% of cells were positive for Sca-1 immediately after separation) and Sca-1-depleted fractions (Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin−; less than 5% of cells were positive for Sca-1) by using magnetic beads coated with Sca-1 antibody. Figure 1A shows the morphology of Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells. Typical yields of Sca-1-enriched and Sca-1-depleted fractions were 5 × 105 and 2 × 107 cells, respectively, pooled from 10 mice.

FIG. 1.

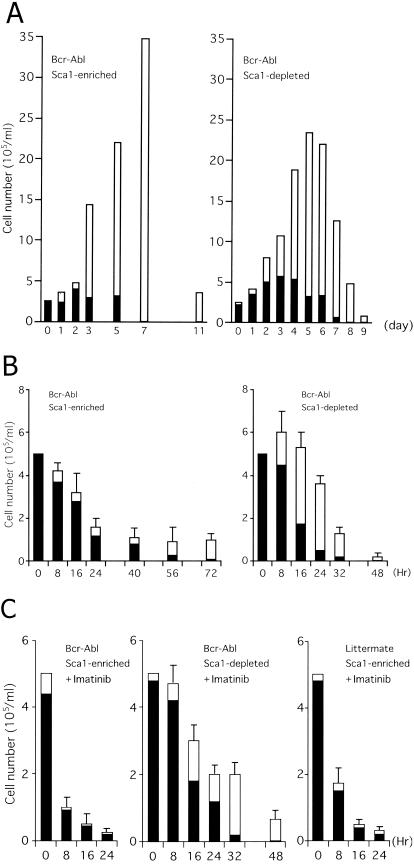

Cytokine-dependent hematopoietic progenitors isolated from mouse bone marrow. (A) Cytospin preparation showing the morphology of Sca-1-positive early hematopoietic progenitors (Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin−) isolated from primary cultures of mouse bone marrow cells visualized by May-Giemsa staining. (B and C) Cultures of Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− (left panels) and Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells (right panels) were continued in the presence (B) or absence (C) of SCF and TPO. The numbers of viable cells were determined by trypan blue dye exclusion. Blast cells (black bars) and terminally differentiated cells (open bars) were quantified by cytospin centrifugation. Results from one representative study (B) and the means and standard errors of results from three independent experiments (C) are shown. (D) Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells were cultured in cytokine-free medium for the indicated periods. Cells were harvested, the TUNEL assay was performed with fluorescein-dUTP, and cells were stained with propidium iodide. Cytospin preparations were made and analyzed with a laser cytoscan.

Cells in both fractions proliferated and differentiated into mature granulocytes or monocytes when culture was continued in medium containing TPO and SCF (Fig. 1B). Cell numbers increased by around 10-fold by 5 days and then decreased, and cultures died out 10 days later. Although peak cell numbers of the progeny of Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells were always greater than those of Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells, the time courses were similar. When culture was continued in the absence of cytokines, Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells rapidly died within 24 h without maturation (Fig. 1C, left panel). Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells also died but did so more slowly than Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells, and nearly half differentiated into mature granulocytes or monocytes (Fig. 1C, right panel). To confirm that the cell death observed in these experiments was apoptotic, we performed TUNEL assays (Fig. 1D). When Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells were cultured in the presence of cytokines, there was a substantial number in S phase with few TUNEL-positive cells among them (Fig. 1D, left panel). In contrast, in the absence of cytokines, cells underwent G0/G1 arrest with many TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 1D, center and right panels). These results indicated that the cell division and survival of Sca-1-positive early hematopoietic progenitors isolated by this method were cytokine dependent.

Upregulation of Bim and downregulation of Bcl-2 in cytokine-deprived hematopoietic progenitors.

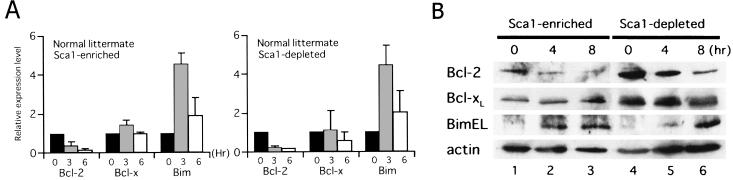

To elucidate the contribution of Bcl-2 superfamily members to cytokine-dependent cell survival in hematopoietic progenitors, expression levels of A1, Bad, Bax, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, BimEL, Mcl-1, and DP5/Hrk mRNA were assessed by using real-time quantitative RT-PCR technology. In both Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− and Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells from normal littermates, rapid downregulation of Bcl-2 and upregulation of BimEL were consistently observed in independent experiments (Fig. 2A), while mRNA expression of other Bcl-2 superfamily members did not change significantly upon cytokine deprivation (data not shown). Although downregulation of Bcl-xL following cytokine deprivation has been observed in many cytokine-dependent cell lines, including Baf-3, FL5.12, and 32D (27, 28, 39), Bcl-xL expression in hematopoietic progenitors isolated by this method was not affected by cytokine deprivation (Fig. 2A). These findings were further supported at the protein level by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2B); simultaneous downregulation of Bcl-2 and upregulation of BimEL were observed, while Bcl-xL remained unchanged in both Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− and Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells. Importantly, the levels of the two antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 were 5- to 10-fold lower in Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells than in Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells, possibly explaining the rapid apoptosis observed in the former (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that the induction of Bim by cytokine deprivation plays an important role in regulating cell fate in Sca-1-positive early progenitors.

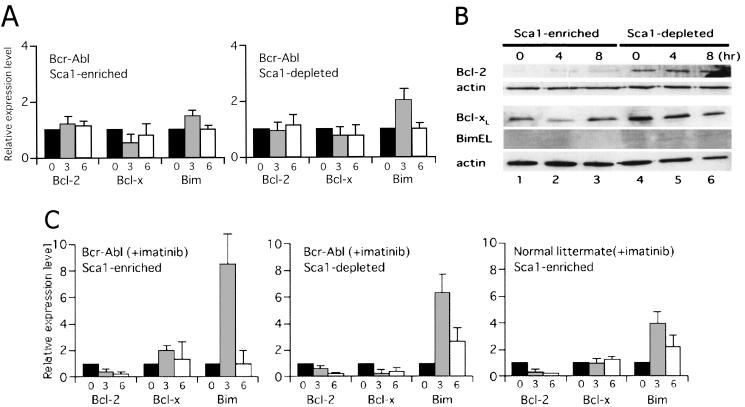

FIG. 2.

Expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and BimEL in Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− and Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells from normal mice. Cells were cultured in the absence of cytokines for the indicated times. (A) Real-time quantitative PCR was carried out, and the numbers of cycles required to produce a detectable product were measured and used to calculate differences (n-fold) in starting mRNA levels for each sample by using 28S rRNA as an internal control. mRNA expression levels in cells cultured for 0 (black bars), 3 (gray bars), and 6 (open bars) h without cytokines relative to those in cells cultured in the presence of cytokines are shown. (B) Protein expression levels of the three Bcl-2 superfamily members, as well as β-actin as a control for equal loading, were analyzed by immunoblotting with specific antibodies for each protein.

Bcr-Abl reverses the upregulation of Bim by IL-3 deprivation in IL-3-dependent cells.

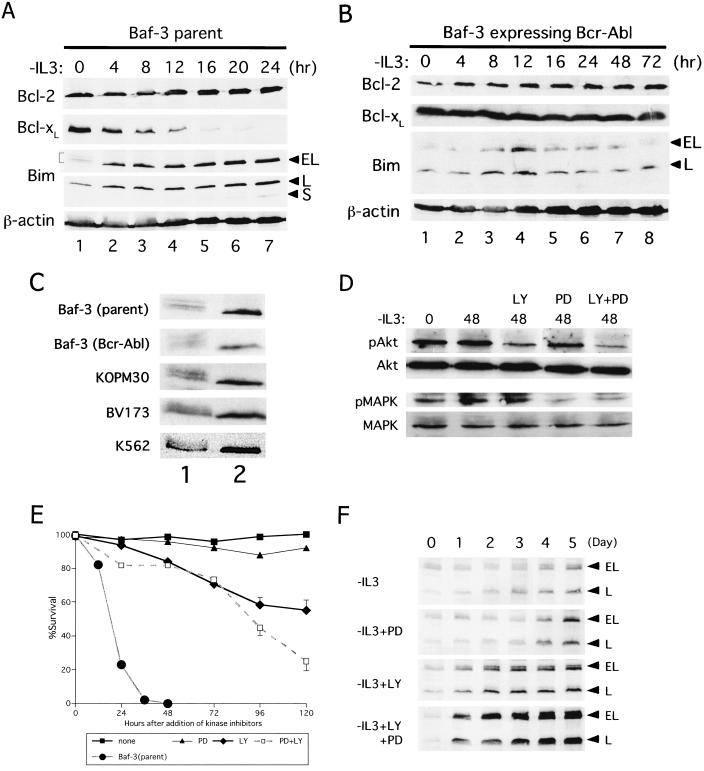

To test whether Bcr-Abl downregulates Bim expression, we initially used Baf-3 cells expressing Bcr-Abl. Baf-3 cells were infected with retrovirus containing Bcr-Abl and mouse CD8 cDNA as a marker (pMX-Bcr-Abl/IRES-CD8; see Materials and Methods), and infected cells were selected with magnetic beads coated with CD8 antibodies. As reported by others (11, 28), these cells proliferated in IL-3-free medium at nearly the same rate as they did in IL-3-containing medium (data not shown). As previously reported (13, 44), the simultaneous downregulation of Bcl-xL and upregulation of Bim were induced by IL-3 starvation in wild-type Baf-3 cells (Fig. 3A). In Baf-3 cells expressing Bcr-Abl, Bcl-xL expression levels were unaffected, while Bim protein was induced for 12 h after IL-3 deprivation, and then the level of Bim declined and returned to its original level within 3 days (Fig. 3B). It was also reported previously that BimEL is phosphorylated by IL-3 signaling (44), shown here by slower migrating bands (Fig. 3A, lane 1, and C, top blot). Similar slower migrating bands were observed in Baf-3 cells expressing Bcr-Abl in the absence of IL-3 [Fig. 3B and C, blots labeled Bim and Baf-3 (Bcr-Abl)], suggesting that Bcr-Abl also phosphorylates BimEL.

FIG. 3.

Bim expression is regulated by IL-3 or Bcr-Abl through Raf/MAPK and/or PI3-K pathways in Baf-3 cells. EL, BimEL; L, BimL; S, BimS. (A and B) Expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Bim proteins in wild-type Baf-3 cells (A) and Baf-3 cells expressing Bcr-Abl after infection with a retrovirus vector (B). Cells were cultured in the absence of IL-3 for the indicated times. An immunoblot analysis using antibody specific for each protein was performed. A bracket in panel A indicates the phosphorylated forms of BimEL. (C) Phosphorylation of BimEL protein. Parental Baf-3 cells were cultured in the presence of IL-3 (lane 1) or in the absence of IL-3 (lane 2) for 4 h; IL-3-starved and Bcr-Abl expressing Baf-3, KOPM30, BV173, and K562 cells were cultured in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lane 2) of imatinib for 12 h. (D to F) Baf-3 cells expressing Bcr-Abl were cultured in IL-3-free medium for 72 h and then treated with PD, LY, or both (LY+PD) at a concentration of 50 μM for the indicated times (in hours). Immunoblot analyses using anti-phosphorylated form-specific Akt or MAPK, as well as antibodies recognizing total Akt or MAPK (D) or anti-Bim antibody (F), were performed. (E) Cell viability was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion. The survival curve of parental Baf-3 cells is shown as a control. Standard errors are shown when they were greater than 3%.

In wild-type Baf-3 cells, it was demonstrated previously that signals from the distal portion of the βc chain independently downregulate Bim expression through both the classical Ras/Raf/MAPK and Ras/PI3-K pathways (44). To test whether Bcr-Abl downregulates Bim expression via the same signaling pathways in this particular cell system, Baf-3 cells expressing Bcr-Abl were cultured in the absence of IL-3 for 3 days, after which they were treated with the MAPK inhibitor PD, the PI3-K inhibitor LY, or both. The effects of these inhibitors were monitored by immunoblot analysis using antibodies recognizing phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) or phosphorylated MAPK. When cells were treated with PD, phosphorylated MAPK but not pAkt decreased, and viability was slightly reduced (Fig. 3D and E). When cells were treated with LY or both PD and LY together, levels of pAkt decreased, and massive cell death occurred. Immunoblot analysis revealed a mild enhancement of Bim expression in cells treated with PD, while a marked elevation was observed in cells treated with LY or both kinase inhibitors (Fig. 3F). These results suggest that, although both Raf/MAPK and PI3-K pathways contribute to cell survival and the downregulation of Bim by Bcr-Abl kinase, PI3-K pathways are more important than Raf/MAPK pathways in this particular cell system.

Bim expression is downregulated in cells expressing Bcr-Abl from patients with leukemia.

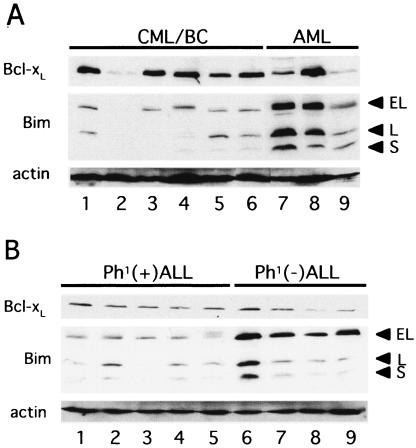

To gain insight into the roles of Bim in the process of human leukemogenesis, we quantified the levels of Bim and Bcl-xL proteins in cell lines established from patients in the BC phase of CML (CML/BC) and from patients with Philadelphia chromosome (Ph1)-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and compared them with the levels in patients with human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and ALL cell lines that do not express the Bcr-Abl fusion gene. Levels of Bim in all six cell lines established from patients in CML/BC were low (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 to 6) compared with those in three control AML cell lines (Fig. 4A, lanes 7 to 9). Low levels of Bim, especially BimEL, in Ph1-positive cells were also observed in five cell lines established from patients with ALL (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 to 5). In contrast, levels of Bcl-xL varied among cell lines established from patients in CML/BC and patients with AML (Fig. 4A), as expected based on results from previous studies reporting that Bcl-xL expression levels differ among AML patients (43). The levels of Bcl-xL in all ALL cell lines with or without Bcr-Abl expression seemed consistently low compared with those in AML cell lines (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Levels of Bcl-xL and Bim protein in human leukemia cell lines. Immunoblot analysis using antibody specific for each protein was performed. EL, BimEL; L, BimL; S, BimS. (A) Lanes 1 to 6, the KOPM28, KOPM30, KOPM53, K562, BV173, and KU812 cell lines, respectively, established with CML/BC cells; lanes 7 to 9, the HL60 myeloid leukemia, HEL erythroid leukemia, and U937 monocytic leukemia cell lines, respectively, lacking Ph1. (B) Lanes 1 to 5, the KOPN-55bi, KOPN-57bi, KOPN-66bi, KOPN-72bi, and KOPN-30bi Ph1-positive pro-B ALL cell lines, respectively; lanes 6 to 9, the 920, 697, RS4;11, and UOC-B1 pro-B ALL cell lines, respectively, lacking Ph1.

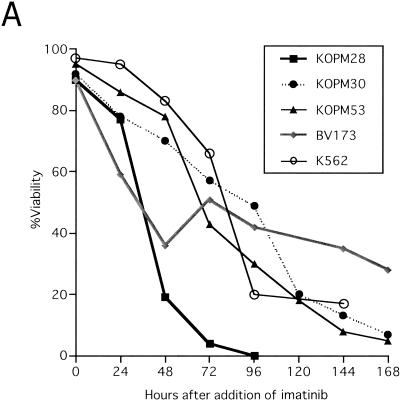

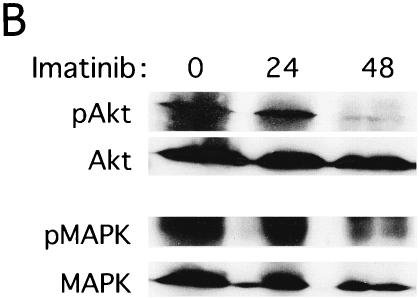

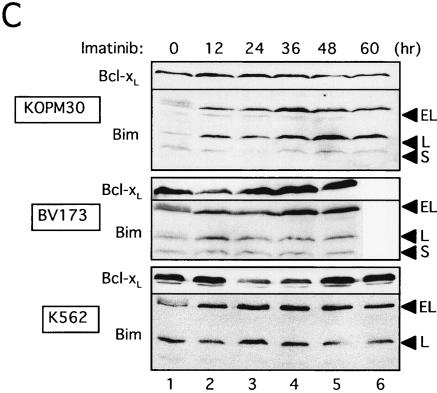

To test whether the low level of Bim protein expression in Ph1-positive leukemia cells was due to the potential of Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase to downregulate it (as shown in Fig. 3B), we blocked Bcr-Abl function by using a specific inhibitor of Abl kinase, imatinib mesylate (formerly known as STI571). As previously reported (12, 24), apoptosis was induced by imatinib in five cell lines established from patients in CML/BC, and dephosphorylation of Akt and MAPK was observed in these cells (Fig. 5A and B). Increased levels of Bim proteins, especially BimEL and BimL, were induced by the addition of imatinib to KOPM30, K562, and BV173 cells (Fig. 5C). Moreover, dephosphorylation of BimEL was observed (Fig. 3C), suggesting that Bcr-Abl phosphorylates BimEL or BimL in human Ph1-positive leukemia cells. Expression levels of Bcl-xL were not altered in KOPM30 and were downregulated only transiently in K562 and BV173 cells (Fig. 5C). Similar results were obtained with KOPM28 and KOPM53 (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

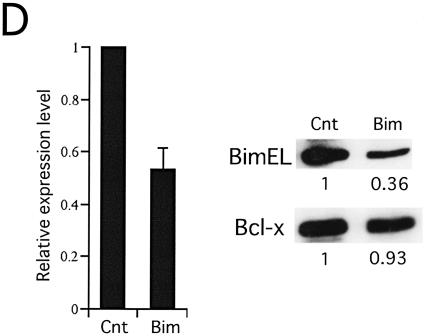

Effects of imatinib on cell lines established with CML/BC cells. (A) Cell lines (KOPM28, KOPM30, KOPM53, BV173, and K562) established with cells from CML/BC patients were cultured in medium containing imatinib at a concentration of 1 μM for the indicated times. Viability was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion. (B) Immunoblot analyses of K562 cell lysate using anti-phosphorylated form-specific Akt or MAPK, as well as antibodies recognizing total Akt or MAPK, were performed. (C) Levels of Bcl-xL and Bim proteins in KOPM30, BV173, and K562 cells were determined by immunoblot analysis. EL, BimEL; L, BimL; S, BimS. (D) K562 cells transfected with either Bim siRNA (Bim) or control siRNA (Cnt) were cultured in the presence of 1 μM imatinib for 48 h. The results of real-time RT-PCR using the Bim(si) primers (left panel) and an immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific for Bim (upper right panel) or Bcl-xL (lower right panel) are shown. Numbers below the immunoblots indicate the relative intensity of each band measured by densitometry. (E) K562 cells were cultured in the absence of imatinib (upper left panel), the presence of 1 μM imatinib for 48 h with mock transfection (upper right panel), Cy3-labeled control siRNA (lower left panel), or Cy3-labeled Bim siRNA (lower right panel). Cells were stained with annexin V-FITC and analyzed by flow cytometry.

To examine whether the upregulation of Bim expression contributes to apoptosis induced by imatinib, K562 cells were transfected with Cy3-labeled siRNA oligonucleotides homologous to the Bim sequence or control siRNA (42). The induction efficiency was judged to be around 60% based on observations with fluorescence microscopy (data not shown). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis using a primer set to cross the cleavage site [Bim(si)] (Table 1) revealed a 45% reduction of Bim mRNA by the Bim siRNA when whole cells were analyzed (Fig. 5D, left panel). Immunoblot analysis revealed a greater-than-60% reduction of Bim protein, while Bcl-xL analyzed as a control was reduced by less than 10% (Fig. 5D, right panel). The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined with annexin V-FITC. Cells transfected with Bim siRNA showed a significantly lower percentage of annexin V-positive cells (68.1% ± 7.3% [average ± standard deviation]) than those transfected with control siRNA (38.1% ± 9.3%) (Fig. 5E). These data suggest that Bcr-Abl supports cell survival in cell lines established from patients in CML/BC through the downregulation of Bim, although it was not clear whether the magnitude of Bim induction in these cells was sufficient to account for all of the apoptosis caused by imatinib.

Prolonged survival of Sca-1-positive early progenitors from Bcr-Abl tg mice in cytokine-free medium.

Cell lines established with cells in CML/BC harbor additional abnormalities that develop during progression to BC and/or during adaptation to the ex vivo artificial culture environment. To test whether Bcr-Abl downregulates Bim expression in cells from patients in the chronic phase of CML, we used progenitors expressing Bcr-Abl from primary cultures of bone marrow cells obtained from Bcr-Abl tg mice that always develop CML-like myeloproliferative disease (see the introduction). Their survival and levels of Bcl-2 superfamily member expression were compared with those of their normal littermates.

Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− and Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells were isolated from primary cultures of bone marrow cells from the tg mice. When these cells were cultured in the presence of cytokines, they proliferated with kinetics similar to those of cells from the normal littermates of the tg mice (Fig. 6A), although cell numbers from the tg mice were greater than those from their normal littermates in both fractions (Fig. 1B). When Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells were cultured in cytokine-free medium, they survived for more than 3 days (Fig. 6B, left panel), much longer than those from normal littermates (Fig. 1C, left panel). Indeed, virtually no viable cells from normal littermates were observed 24 h after cytokine deprivation, while cells with immature and mature morphology from Bcr-Abl tg mice survived even after 48 h in repeated experiments. In contrast, Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells underwent apoptosis with kinetics similar to those of cells from the normal littermates (Fig. 1C, right panel). To confirm that Bcr-Abl prolongs the survival of Sca-1-positive early hematopoietic progenitors in cytokine-free medium, we added 1 μM imatinib to the culture medium. Imatinib did not affect the survival of the Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells (Fig. 6C, middle panel). In contrast, Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells rapidly underwent apoptosis (Fig. 6C, left panel). A comparison of the numbers of living cells with those of Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells from normal mice (Fig. 1C) revealed that imatinib seemed not only to reverse the antiapoptotic effects of Bcr-Abl but even to enhance apoptosis at 8 and 16 h. This finding might be explained in part by the inhibitory effects of imatinib against c-Kit function, which could persist after the removal of SCF because imatinib also induced apoptosis in Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells from normal mice at 8 h (not statistically significant; P = 0.14) and 16 h (P < 0.05) after the removal of the cytokines (Fig. 6C, right panel). These data suggest that Bcr-Abl protects Sca-1-positive early progenitors, but not Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells, from apoptosis caused by cytokine deprivation. Bcr-Abl mRNA expression was detected by RT-PCR in both fractions (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

(A and B) Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells (left panel) and Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells (right panel) amplified and isolated by primary cultures of bone marrow cells from Bcr-Abl tg mice were cultured in the presence (A) or absence (B) of SCF and TPO. (C) Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells (left and right panels) or Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells (middle panel) amplified and isolated by primary cultures of bone marrow cells from Bcr-Abl tg mice (left and middle panels) or their normal littermates (right panel) were cultured in the absence of SCF and TPO. Imatinib was added at a concentration of 1 μM. The number of viable cells was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion. Blast cells (black bars) and terminally differentiated cells (open bars) were determined by cytospin centrifugation. The results from one representative study (A) or the means + standard errors of results from three independent experiments (B and C) are shown.

Suppression of Bim induction in cytokine-deprived progenitors by Bcr-Abl.

To clarify the mechanism through which Bcr-Abl prolongs survival of Sca-1-positive progenitors, we assessed the expression of Bcl-2 superfamily members in these cells. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR revealed that neither Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, nor Bim mRNA expression was altered by cytokine deprivation in either Sca-1-positive or Sca-1-negative cells, except that Bim mRNA was induced twofold in Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells (Fig. 7A). These data were confirmed at the protein level by immunoblot analysis. Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL levels were unchanged by cytokine deprivation, while Bim protein was barely detectable in either fraction (Fig. 7B), in contrast to a clear induction of Bim and downregulation of Bcl-2 in progenitors from normal littermates (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 7.

Expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and BimEL in Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− and Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells from Bcr-Abl tg mice and their normal littermates. Cells were cultured in cytokine-free medium in the absence (A and B) or presence (C) of imatinib at a concentration of 1 μM for the indicated times. (A and C) Real-time quantitative PCR was carried out, and the numbers of cycles required to produce a detectable product were measured and used to calculate the differences (n-fold) in starting mRNA levels for each sample by using 28S rRNA as an internal control. Levels of mRNA in cells cultured for 0 (black bars), 3 (gray bars), and 6 (open bars) h without cytokines relative to those in cells in the presence of cytokines are shown. (B) Levels of three Bcl-2 superfamily members, as well as β-actin proteins, as a control for equal loading were detected by specific antibodies.

To further confirm that Bcr-Abl downregulates Bim, we analyzed the expression of the Bcl-2 superfamily members in cells cultured in cytokine-free medium in the presence of imatinib. Bim was markedly induced, while Bcl-2 was downregulated in Sca-1-positive and -negative progenitors isolated from Bcr-Abl tg mice (Fig. 7C, left and center panels). In contrast, induction levels of Bim in Sca-1-positive progenitors isolated from normal littermates were not changed by treatment with imatinib (Fig. 7C, right panel, and 2A, left panel), suggesting that the reduction of viable cells in progenitors from normal littermates by imatinib (Fig. 6C, right panel) was due to mechanisms other than Bim induction. Taken together, these data indicate that Bcr-Abl reverses the downregulation of Bcl-2 and upregulation of Bim that are observed in cytokine-starved normal hematopoietic progenitors.

DISCUSSION

In earlier studies, it was established that the induction of Bim is an important step in Baf-3 cells undergoing apoptosis due to IL-3 deprivation (44). Here we demonstrate that Bim was induced by cytokine starvation in early hematopoietic progenitors (Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin−) isolated by primary short-term culture of bone marrow cells from normal mice. In contrast, Bim was not induced by cytokine starvation in early progenitors from CML model mice that were more resistant to apoptosis than those from normal mice. We also found that Bcr-Abl downregulates Bim expression in Baf-3 cells and cell lines established with cells from patients with Ph1-positive leukemia, suggesting that Bim is one of the key target factors downstream of Bcr-Abl that render CML progenitors resistant to apoptosis caused by cytokine deprivation.

The function of Bim is reported to be regulated by at least four different mechanisms. First, mRNA expression is downregulated by cytokines in mouse IL-3-dependent Baf-3, FL5.12, and 32D cells through the Ras/MAPK and PI3-K pathways, independently (13, 44). Moreover, NGF suppresses Bim mRNA expression through the inactivation of the c-jun NH2-terminal kinase in NGF-dependent neuronal cells, including primary cultures of rat sympathetic neurons and neuronally differentiated PC-12 cells (5, 40, 49). In addition, serum deprivation of CC139 fibroblasts upregulates Bim mRNA via the classical MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway (48). Second, subcellular localization of Bim is controlled by IL-3 in FDC-P1 cells, another mouse IL-3-dependent line, and by exposure to UV light in 293 cells (29, 41). BimEL and BimL, but not BimS, form complexes with an 8,000-molecular-weight dynein light chain, LC8 (also PIN or Dlc-1) (10, 21, 25). The Bim/LC8 complex in the presence of IL-3 binds to the intermediate chain of the dynein motor complex on the microtubules. IL-3 withdrawal releases the complex from sequestration in the cytoplasm by mechanisms not yet fully understood. In the case of 293 cells exposed to UV, phosphorylation at Thr-56 of (human) BimL by activated c-jun NH2-terminal kinase was reported to play an important role in this process (29). Third, NGF phosphorylates BimEL and BimL but not BimS through the MEK/MAPK pathway in neuronally differentiated PC-12 cells. Phosphorylation of (rat) BimEL at Ser-109 and Thr-110, which are adjacent to but distinct from the phosphorylation residues in 293 cells exposed to UV as mentioned above, was reported to suppress the proapoptotic function of BimEL without affecting its binding potential to LC8 or its subcellular localization (5). Fourth, proteasome-dependent degradation is involved in the regulation of Bim expression in serum-deprived fibroblasts and macrophage colony-stimulating factor-dependent osteoclasts (2, 31). These somewhat confusing results suggest that the functions of BimEL and BimL on the one hand and BimS on the other may be regulated in different ways in certain situations and that the relative importance of these four mechanisms may differ between cell types. Indeed, it has been found that the enforced expression of either BimL or BimS readily induced apoptosis in Baf-3 and 293 cells, in contrast with five glioma cell lines, in which a massive amount of BimL did not induce apoptosis, in spite of the fact that a much lower amount of BimS easily killed these cells (44, 50).

In this paper, we demonstrated that Bim is downregulated at both the mRNA and protein levels by cytokines in hematopoietic progenitors isolated from primary cultures of bone marrow cells (Fig. 2). This finding indicates that the regulation of mRNA expression is the major mechanism for controlling Bim function in early hematopoiesis. We also demonstrated that Bcr-Abl reverses the induction of Bim mRNA caused by cytokine deprivation in these progenitors (Fig. 7). Among several pathways that are reported to regulate Bim mRNA, those involved in PI3-K are most likely the major pathways for the downregulation of Bim by Bcr-Abl (Fig. 3F). In addition, phosphorylation of Bim (as with the third mechanism mentioned in the previous paragraph) might contribute to the survival of hematopoietic cells. It was previously reported that BimEL and BimL are phosphorylated in Baf-3 cells by IL-3 signaling via the same pathways that control the expression of Bim, i.e., the Ras/Raf/MAPK and Ras/PI3-K pathways (44). In this study, although the phosphorylation of BimEL in early progenitors may not be convincing (Fig. 2B), it was clearly detected in Baf-3 cells expressing Bcr-Abl cultured in IL-3-free medium and in cell lines established from patients in CML/BC cultured in the absence of imatinib (Fig. 3C). We consider it unlikely that phosphorylation plays a major role in cytokine-deprived Baf-3 cells, because cells expressing hyperphosphorylated BimEL or BimL in the presence of IL-3 still underwent apoptosis (44). However, the possibility that phosphorylation of BimEL and BimL by cytokines or Bcr-Abl contributes to cell survival to some extent in early hematopoietic progenitors or leukemic cells cannot be excluded.

There are substantial differences between early (Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin−) and late (Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin−) progenitors in cytokine dependence and the effects of Bcr-Abl kinase. Early progenitors undergo rapid apoptosis without maturation in the absence of cytokines (Fig. 1C). This could be explained at least partially by relatively low levels of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression (Fig. 2B), because it is generally accepted that cell fate is determined by the balance between pro- and antiapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 superfamily (1). Although Bcl-2 levels were downregulated by cytokine deprivation in early progenitors, this downregulation is unlikely to be the major cause of rapid apoptosis, because levels of Bcl-2 in the presence of cytokines are very low and Bcl-2-deficient mice did not show apparent abnormalities in myeloid hematopoiesis (34, 47). Thus, Bim is considered to be the major determinant of cell fate in Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− cells, and downregulation of Bim in cytokine-deprived Sca-1-positive early progenitors isolated from Bcr-Abl tg mice may result in longer survival (Fig. 6B). On the other hand, Bim may not be the major determinant of cell fate in Sca-1− c-Kit+ Lin− cells, which express Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL at high levels (Fig. 2B). Moreover, half of these cells can differentiate before undergoing apoptosis (Fig. 1C). Additionally, late progenitors from the tg mice show virtually the same time course as those from normal littermates in the absence of cytokines (Fig. 1C and 6B, right panels) in spite of the fact that there was little induction of Bim in these cells, similar to Sca-1-positive early progenitors (Fig. 7A and B).

Many reports have maintained that the growth and survival characteristics of CML progenitors in the chronic phase are similar to those in healthy bone marrow (reviewed in references 15 and 23). In spite of prominent antiapoptotic effects of Bcr-Abl in cytokine-dependent cell lines such as Baf-3, resistance of CML progenitors to cytokine deprivation is controversial. Bedi et al. reported that CD34-positive CML progenitors live longer in serum- and cytokine-free medium than CML progenitors treated with Bcr-Abl junction-specific antisense oligonucleotides and normal CD34-positive cells (4), but Amos et al. did not observe a survival advantage of CML progenitors under cytokine-free conditions (3). In the present study, we isolated early hematopoietic progenitors by using Sca-1, which is one of the most reliable markers for early progenitors, including stem cells, but is available only for the study of mouse hematopoiesis. Another advantage of our study is the use of progenitors isolated from young mice (8 to 12 weeks of age) whose peripheral blood and bone marrow are still indistinguishable from those of their normal littermates (18). Taking these advantages, we revealed a relatively small but distinct difference in apoptosis due to cytokine deprivation between normal and Bcr-Abl-expressing progenitors that correlated to the expression levels of Bim (Fig. 1, 2, 6, and 7). Moreover, Bim was induced by imatinib in CML cell lines undergoing apoptosis (Fig. 5C), and siRNA that reduced the expression level of Bim effectively rescued these cells (Fig. 5E). Taken together, these results suggest that Bim is an important downstream target that supports cell survival of Bcr-Abl-expressing hematopoietic cells. Further studies are necessary to clarify whether downregulation of Bim by Bcr-Abl contributes to the massive expansion of myeloid cells observed in CML.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; the Novartis Foundation (Japan) for the promotion of Science; the Yamanouchi Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders; the Takeda Science Foundation; the Naito Foundation; the Uehara Memorial Foundation; the Sagawa Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research; and the Princess Takamatsu Cancer Research Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, J. M., and S. Cory. 1998. The Bcl-2 protein family: arbiters of cell survival. Science 281:1322-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akiyama, T., P. Bouillet, T. Miyazaki, Y. Kadono, H. Chikuda, U. I. Chung, A. Fukuda, A. Hikita, H. Seto, T. Okada, T. Inaba, A. Sanjay, R. Baron, H. Kawaguchi, H. Oda, K. Nakamura, A. Strasser, and S. Tanaka. 2003. Regulation of osteoclast apoptosis by ubiquitylation of proapoptotic BH3-only Bcl-2 family member Bim. EMBO J. 22:6653-6664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amos, T. A., J. L. Lewis, F. H. Grand, R. P. Gooding, J. M. Goldman, and M. Y. Gordon. 1995. Apoptosis in chronic myeloid leukaemia: normal responses by progenitor cells to growth factor deprivation, X-irradiation and glucocorticoids. Br. J. Haematol. 91:387-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedi, A., B. A. Zehnbauer, J. P. Barber, S. J. Sharkis, and R. J. Jones. 1994. Inhibition of apoptosis by BCR-ABL in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 83:2038-2044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biswas, S. C., and L. A. Greene. 2002. Nerve growth factor (NGF) down-regulates the Bcl-2 homology 3 (BH3) domain-only protein Bim and suppresses its proapoptotic activity by phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:49511-49516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouillet, P., D. Metcalf, D. C. S. Huang, D. M. Tarlinton, T. W. H. Kay, F. Koentgen, J. M. Adams, and A. Strasser. 1999. Proapoptotic Bcl-2 relative Bim required for certain apoptotic responses, leukocyte homeostasis, and to preclude autoimmunity. Science 286:1735-1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chao, D. T., and S. J. Korsmeyer. 1998. BCL-2 family: regulators of cell death. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16:395-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortez, D., L. Kadlec, and A. M. Pendergast. 1995. Structural and signaling requirements for BCR-ABL-mediated transformation and inhibition of apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5531-5541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortez, D., G. Stoica, J. H. Pierce, and A. M. Pendergast. 1996. The BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibits apoptosis by activating a Ras-dependent signaling pathway. Oncogene 13:2589-2594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crépieux, P., H. Kwon, N. Leclerc, W. Spencer, S. Richard, R. Lin, and J. Hiscott. 1997. IκBα physically interacts with a cytoskeleton-associated protein through its signal response domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:7375-7385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daley, G. Q., and D. Baltimore. 1988. Transformation of an interleukin 3-dependent hematopoietic cell line by the chronic myelogenous leukemia-specific P210bcr/abl protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:9312-9316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deininger, M. W., J. M. Goldman, N. Lydon, and J. V. Melo. 1997. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor CGP57148B selectively inhibits the growth of BCR-ABL-positive cells. Blood 90:3691-3698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dijkers, P. F., R. H. Medema, J.-W. J. Lammers, L. Koenderman, and P. J. Coffer. 2000. Expression of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bim is regulated by the forkhead transcription factor FKHR-L1. Curr. Biol. 10:1201-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dumon, S., S. C. Santos, F. Debierre-Grockiego, V. Gouilleux-Gruart, L. Cocault, C. Boucheron, P. S Mollat, S. Gisselbrecht, and F. Gouilleux. 1999. IL-3 dependent regulation of Bcl-xL gene expression by STAT5 in a bone marrow derived cell line. Oncogene 18:4191-4199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holyoake, D. T. 2001. Recent advances in the molecular and cellular biology of chronic myeloid leukaemia: lessons to be learned from the laboratory. Br. J. Haematol. 113:11-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honda, H., Y. Yamashita, K. Ozawa, and H. Mano. 1996. Cloning and characterization of mouse tec promoter. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 223:422-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honda, H., K. Ozawa, Y. Yazaki, and H. Hirai. 1997. Identification of PU.1 and Sp1 as essential transcriptional factors for the promoter activity of mouse tec gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 234:376-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honda, H., H. Oda, T. Suzuki, T. Takahashi, O. N. Witte, K. Ozawa, T. Ishikawa, Y. Yazaki, and H. Hirai. 1998. Development of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and myeloproliferative disorder in transgenic mice expressing p210bcr/abl: a novel transgenic model for human Ph1-positive leukemias. Blood 91:2067-2075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honda, H., T. Ushijima, K. Wakazono, H. Oda, Y. Tanaka, S. Aizawa, T. Ishikawa, Y. Yazaki, and H. Hirai. 2000. Acquired loss of p53 induces blastic transformation in p210(bcr/abl)-expressing hematopoietic cells: a transgenic study for blast crisis of human CML. Blood 95:1144-1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu, S. Y., P. Lin, and A. J. Hsueh. 1998. BOD (Bcl-2-related ovarian death gene) is an ovarian BH3 domain-containing proapoptotic Bcl-2 protein capable of dimerization with diverse antiapoptotic Bcl-2 members. Mol. Endocrinol. 12:1432-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaffrey, S. R., and S. H. Snyder. 1996. PIN: an associated protein inhibitor of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Science 274:774-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kabarowski, J. H., P. B. Allen, and L. M. Wiedemann. 1994. A temperature sensitive p210 BCR-ABL mutant defines the primary consequences of BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase expression in growth factor dependent cells. EMBO J. 13:5887-5895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kabarowski, J. H., and O. N. Witte. 2000. Consequences of BCR-ABL expression within the hematopoietic stem cell in chronic myeloid leukemia. Stem Cells 18:399-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawauchi, K., T. Ogasawara, M. Yasuyama, and S. Ohkawa. 2003. Involvement of Akt kinase in the action of STI571 on chronic myelogenous leukemia cells. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 31:11-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King, S. M., E. Barbarese, J. F. Dillman III, R. S. Patel-King, H. Carson, and K. K. Pfister. 1996. Brain cytoplasmic and flagellar outer arm dyneins share a highly conserved Mr 8,000 light chain. J. Biol. Chem. 271:19358-19366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinoshita, T., T. Yokota, K. Arai, and A. Miyajima. 1995. Suppression of apoptotic death in hematopoietic cells by signaling through the IL-3/GM-CSF receptors. EMBO J. 14:266-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuribara, R., T. Kinoshita, A. Miyajima, T. Shinjyo, T. Yoshihara, T. Inukai, K. Ozawa, A. T. Look, and T. Inaba. 1999. Two distinct interleukin-3-mediated signal pathways, Ras-NFIL3 (E4BP4) and Bcl-xL, regulate the survival of murine pro-B lymphocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:2754-2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laneuville, P., N. Heisterkamp, and J. Groffen. 1991. Expression of the chronic myelogenous leukemia-associated p210bcr/abl oncoprotein in a murine IL-3 dependent myeloid cell line. Oncogene 6:275-282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lei, K., and R. J. Davis. 2003. JNK phosphorylation of Bim-related members of the Bcl2 family induces Bax-dependent apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:2432-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leverrier, Y., J. Thomas, G. R. Perkins, M. Mangeney, M. K. L. Collins, and J. Marvel. 1997. In bone marrow derived Baf-3 cells, inhibition of apoptosis by IL-3 is mediated by two independent pathways. Oncogene 14:425-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ley, R., K. Balmanno, K. Hadfield, C. R. Weston, and S. J. Cook. 2003. Activation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway promotes phosphorylation and proteasome-dependent degradation of the BH3-only protein, Bim. J. Biol. Chem. 278:18811-18816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandanas, R. A., H. S. Boswell, L. Lu, and D. Leibowitz. 1992. BCR/ABL confers growth factor independence upon a murine myeloid cell line. Leukemia 6:796-800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mano, H., F. Ishikawa, J. Nishida, H. Hirai, and F. Takaku. 1990. A novel protein-tyrosine kinase, tec, is preferentially expressed in liver. Oncogene 5:1781-1786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuzaki, Y., K. Nakayama, K. Nakayama, T. Tomita, M. Isoda, D. Y. Loh, and H. Nakauchi. 1997. Role of bcl-2 in the development of lymphoid cells from the hematopoietic stem cell. Blood 89:853-862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyajima, A., Y. Ito, and T. Kinoshita. 1999. Cytokine signaling for proliferation, survival, and death in hematopoietic cells. Int. J. Hematol. 69:137-146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Connor, L., A. Strasser, L. A. O'Reilly, G. Hausmann, J. M. Adams, S. Cory, and D. C. Huang. 1998. Bim: a novel member of the Bcl-2 family that promotes apoptosis. EMBO J. 17:384-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okabe, M., Y. Uehara, T. Miyagishima, T. Itaya, M. Tanaka, Y. Kuni-Eda, M. Kurosawa, and T. Miyazaki. 1992. Effect of herbimycin A, an antagonist of tyrosine kinase, on bcr/abl oncoprotein-associated cell proliferations: abrogative effect on the transformation of murine hematopoietic cells by transfection of a retroviral vector expressing oncoprotein P210bcr/abl and preferential inhibition on Ph1-positive leukemia cell growth. Blood 80:1330-1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Onishi, M., S. Kinoshita, Y. Morikawa, A. Shibuya, J. Phillips, L. L. Lanier, D. M. Gorman, G. P. Nolan, A. Miyajima, and T. Kitamura. 1996. Application of retrovirus-mediated expression cloning. Exp. Hematol. 24:324-329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Packham, G., E. L. White, C. M. Eischen, H. Yang, E. Parganas, J. N. Ihle, D. A. Grillot, G. P. Zambetti, G. Nunez, and J. L. Cleveland. 1998. Selective regulation of Bcl-XL by a Jak kinase-dependent pathway is bypassed in murine hematopoietic malignancies. Genes Dev. 12:2475-2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Putcha, G. V., K. L. Moulder, J. P. Golden, P. Bouillet, J. A. Adams, A. Strasser, and E. M. Johnson. 2001. Induction of BIM, a proapoptotic BH3-only BCL-2 family member, is critical for neuronal apoptosis. Neuron 29:615-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puthalakath, H., D. C. Huang, L. A. O'Reilly, S. M. King, and A. Strasser. 1999. The proapoptotic activity of the Bcl-2 family member Bim is regulated by interaction with the dynein motor complex. Mol. Cell 3:287-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reginato, M. J., K. R. Mills, J. K. Paulus, D. K. Lynch, D. C. Sgroi, J. Debnath, S. K. Muthuswamy, and J. S. Brugge. 2003. Integrins and EGFR coordinately regulate the pro-apoptotic protein Bim to prevent anoikis. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaich, M., T. Illmer, G. Seitz, B. Mohr, U. Schakel, J. F. Beck, and G. Ehninger. 2001. The prognostic value of Bcl-xL gene expression for remission induction is influenced by cytogenetics in adult acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 86:470-477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shinjyo, T., R. Kuribara, T. Inukai, H. Hosoi, T. Kinoshita, A. Miyajima, P. J. Houghton, A. T. Look, K. Ozawa, and T. Inaba. 2001. Downregulation of Bim, a proapoptotic relative of Bcl-2, is a pivotal step in cytokine-initiated survival signaling in murine hematopoietic progenitors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:854-864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silva, M., A. Benito, C. Sanz, F. Prosper, D. Ekhterae, G. Nunez, and J. L. Fernandez-Luna. 1999. Erythropoietin can induce the expression of bcl-x(L) through Stat5 in erythropoietin-dependent progenitor cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 274:22165-22169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Socolovsky, M., A. E. Fallon, S. Wang, C. Brugnara, and H. F. Lodish. 1999. Fetal anemia and apoptosis of red cell progenitors in Stat5a−/−5b−/− mice: a direct role for Stat5 in Bcl-X(L) induction. Cell 98:181-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veis, D. J., C. M. Sorenson, J. R. Shutter, and S. J. Korsmeyer. 1993. Bcl-2-deficient mice demonstrate fulminant lymphoid apoptosis, polycystic kidneys, and hypopigmented hair. Cell 75:229-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weston, C. R., K. Balmanno, C. Chalmers, K. Hadfield, S. A. Molton, R. Ley, E. F. Wagner, and S. J. Cook. 2003. Activation of ERK1/2 by deltaRaf-1:ER* represses Bim expression independently of the JNK or PI3K pathways. Oncogene 22:1281-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitfield, J., S. J. Neame, L. Paquet, O. Bernard, and J. Ham. 2001. Dominant-negative c-Jun promotes neuronal survival by reducing BIM expression and inhibiting mitochondrial cytochrome c release. Neuron 29:629-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamaguchi, T., T. Okada, T. Takeuchi, T. Tonda, M. Ohtaki, S. Shinoda, T. Masuzawa, K. Ozawa, and T. Inaba. 2003. Enhancement of thymidine kinase-mediated killing of malignant glioma by BimS, a BH3-only cell death activator. Gene Ther. 10:375-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]