Abstract

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, C22:6n-3) plays a vital role in the enhancement of human health, particularly for cognitive, neurological, and visual functions. Marine microalgae, such as members of the genus Aurantiochytrium, are rich in DHA and represent a promising source of omega-3 fatty acids. In this study, levels of glucose, yeast extract, sodium glutamate and sea salt were optimized for enhanced lipid and DHA production by a Malaysian isolate of thraustochytrid, Aurantiochytrium sp. SW1, using response surface methodology (RSM). The optimized medium contained 60 g/L glucose, 2 g/L yeast extract, 24 g/L sodium glutamate and 6 g/L sea salt. This combination produced 17.8 g/L biomass containing 53.9% lipid (9.6 g/L) which contained 44.07% DHA (4.23 g/L). The optimized medium was used in a scale-up run, where a 5 L bench-top bioreactor was employed to verify the applicability of the medium at larger scale. This produced 24.46 g/L biomass containing 38.43% lipid (9.4 g/L), of which 47.87% was DHA (4.5 g/L). The total amount of DHA produced was 25% higher than that produced in the original medium prior to optimization. This result suggests that Aurantiochytrium sp. SW1 could be developed for industrial application as a commercial DHA-producing microorganism.

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) is an essential polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) required by most vertebrates. In humans, this PUFA has been implicated in the prevention of several diseases, including cardiovascular1 and neurological2 diseases. Current commercial sources of DHA are fish and fish oil. However, this fatty acid, partially due to dietary preferences, is conveniently ingested through supplements or enriched foods. These methods of administration are especially preferred by populations whose diets are low in seafood3. According to a report by Ward and Singh4, a daily dietary intake of 1 g DHA derived from seafood would require the consumption of a large quantity of fish. Moreover, there are possible health risks, such as food poisoning and allergies, associated with the consumption of seafood and fish oils, particularly when there are issues of seawater contamination or toxicity and outbreaks of fish diseases. The risks also include contamination of the fish supply in particular areas and the presence of allergens, which may cause adverse effects to human health, in certain species. These factors often drive consumers' choices away from seafood and related products3. Indeed, health advisories often warn consumers about the risks of consuming fatty fish and large predatory fish, which are particularly prone to contamination. Environmental pollutants, which are hydrophobic in nature, accumulate along the marine food chain, particularly in the lipid depots of fish5. In addition, global catches have been declining steeply over the last three decades, and the number of overfished stocks has been increasing exponentially since the 1950s6,7. The expanding requirements for DHA worldwide are now placing pressure on both fisheries and the fish oil supply8. Therefore, efforts have been made to find alternative sources for omega-3 fatty acid production, such as thraustochytrids and marine diatoms9.

Thraustochytrids are cosmopolitan apochlorotic stramenopile protists that are classified in the class Labyrinthulomycetes within the kingdom Chromista10,11,12. This group of organisms is unique in that they produce high biomass in culture, with a high proportion of lipids, including a high proportion of PUFAs, particularly of the omega-3 series such as DHA13. They are a crucial food resource for higher organisms in marine systems15,16,17, owing to their high productivity in manufacturing DHA14. For this reason, thraustochytrids are receiving much attention as a potential source of enrichment for food and feed18 and as a prospective alternative to fish oil as the main source of DHA. It has long been known that environmental factors are important determinants of the quantity and quality of lipids produced by microalgae such as thraustochytrids19. As such, medium composition may have a decisive role in determining the quantity and quality of DHA produced by thraustochytrids20. The production and storage of lipids by microalgae in response to environmental factors are species-specific19.

In our previous study, a recently isolated Malaysian strain of thraustochytrid, Aurantiochytrium sp. SW1 (previously known as Schizochytrium sp. SW1), was found to contain high amounts of lipid with a PUFA content of more than 50%, of which more than 90% was DHA, under non-optimal conditions. Using factorial screening experiments, glucose, yeast extract, monosodium glutamate (MSG) and sea salt were identified as significant medium components that play vital roles in promoting high biomass production as well as high lipid and DHA accumulation by this strain21. Following the screening experiment, this study was carried out to optimize the levels of these components and investigate their effects on lipid and DHA production using response surface medium optimization.

Results

Effects of medium components on lipid

The amount of lipid accumulated by SW1 varied widely, ranging from 0.24 to 10.41 g/L culture medium, with a maximum to minimum ratio of 44.09. A ratio greater than 10 usually implies that a power transformation is needed to increase the normality of the dataset. However, the normal plot of residuals confirmed that the dataset follows a normal distribution and therefore analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out without any power transformation. Based on the sequential model sum of squares, a quadratic equation was chosen as the fitted model, being the highest order unaliased polynomial with the lowest probability (P) value, insignificant lack of fit and highest R2.

The F- and P-values were used to identify the effect of each factor on the amount of lipid accumulated. From the partial sum of square analysis (as shown in Table 1), it was found that glucose, yeast extract and sea salt as well as the interaction between yeast extract and sea salt are significant model terms in determining the amount of lipid produced by SW1. The F- and P-values of each factor show that yeast extract has the largest effect on lipid production, followed by sea salt, the interaction between yeast extract and sea salt, and glucose.

Table 1. ANOVA for lipid accumulation.

| Source | Sum of squares | Degree of freedom | Mean2 | F value | P > F | Coefficient estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block | 26.98 | 2 | 13.49 | |||

| Model | 216.41 | 14 | 15.46 | 5.87 | 0.0014 | |

| A | 18.40 | 1 | 18.40 | 6.99 | 0.0202 | 0.88 |

| B | 58.35 | 1 | 58.35 | 22.17 | 0.0004 | 1.56 |

| C | 11.43 | 1 | 11.43 | 4.34 | 0.0575 | 0.69 |

| D | 34.41 | 1 | 34.41 | 13.08 | 0.0031 | 1.20 |

| A2 | 3.07 | 1 | 3.07 | 1.17 | 0.2998 | −0.33 |

| B2 | 40.36 | 1 | 40.36 | 15.34 | 0.0018 | −1.21 |

| C2 | 5.41 | 1 | 5.41 | 2.05 | 0.1754 | −0.44 |

| D2 | 23.42 | 1 | 23.42 | 8.90 | 0.0106 | −0.92 |

| AB | 5.85 | 1 | 5.85 | 2.22 | 0.1597 | 0.60 |

| AC | 0.31 | 1 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.7383 | −0.14 |

| AD | 6.41 | 1 | 6.41 | 2.44 | 0.1426 | 0.63 |

| BC | 0.056 | 1 | 0.056 | 0.021 | 0.8864 | −0.06 |

| BD | 23.95 | 1 | 23.95 | 9.10 | 0.0099 | 1.22 |

| CD | 0.15 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.056 | 0.8167 | −0.10 |

| Residuals | 34.21 | 13 | 2.63 | |||

| Lack of fit | 33.03 | 10 | 3.30 | 8.40 | 0.0632 | |

| Pure error | 1.18 | 3 | 0.39 | |||

| Cor total | 277.61 | 29 |

P < 0.05 is significant.

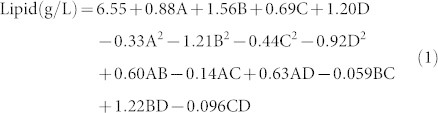

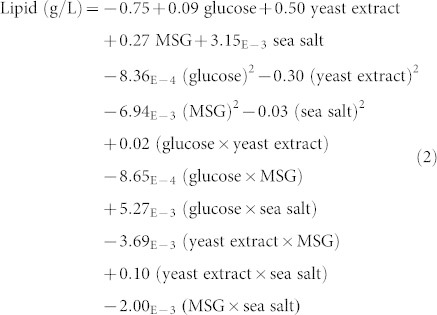

The experimental values obtained from the central composite design (CCD) were regressed using a quadratic polynomial equation, and the two regression equations, expressed in terms of the coded and actual factors, are shown below.

Final equation in terms of coded factors:

|

Final equation in terms of actual factors:

|

Effects of medium components on DHA

The highest percentage of DHA was produced in standard run number 8, where DHA accounts for 48.6% of the total lipid, whereas the lowest percentage was produced in standard run number 29 (14.5% of total lipid). The ratio of maximum to minimum is 3.34, showing that a power transformation step is not necessary. In accordance with this ratio, the normal plot of residuals showed that the dataset follows a normal distribution. Similar to the response of lipid discussed above, the sequential model sum of squares, lack of fit test and R2 value showed that a quadratic equation is the suitable model for regression of the experimental data. Upon choosing the fitted model, an ANOVA was conducted to obtain the F and P-values for the factors involved.

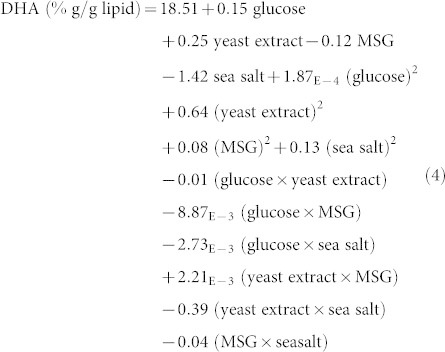

Table 2 shows the ANOVA results for DHA accumulation. From this table, it can be observed that MSG and sea salt as well as the interaction between yeast extract and sea salt have significant effects on the percentage of DHA in lipid accumulated by SW1. The order of effects of significant factors on percentage of DHA is: sea salt > interaction between yeast extract and sea salt > MSG. The final equations for the response of DHA in terms of the factors are given below:

Table 2. ANOVA for DHA accumulation.

| Source | Sum of squares | Degree of freedom | Mean2 | F value | P > F | Coefficient estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block | 46.37 | 2 | 23.19 | |||

| Model | 2905.88 | 14 | 207.56 | 8.47 | 0.0002 | |

| A | 37.50 | 1 | 37.50 | 1.53 | 0.2379 | 1.25 |

| B | 2.30 | 1 | 2.30 | 0.094 | 0.7643 | −0.31 |

| C | 153.30 | 1 | 153.30 | 6.26 | 0.0265 | 2.53 |

| D | 1053.35 | 1 | 1053.35 | 42.99 | <0.0001 | −6.62 |

| A2 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.15 | 6.258E-3 | 0.9381 | 0.08 |

| B2 | 181.64 | 1 | 181.64 | 7.41 | 0.0174 | 2.57 |

| C2 | 634.40 | 1 | 634.40 | 25.89 | 0.0002 | 4.81 |

| D2 | 624.94 | 1 | 624.94 | 25.51 | 0.0002 | 4.77 |

| AB | 2.81 | 1 | 2.81 | 0.11 | 0.7405 | −0.42 |

| AC | 32.23 | 1 | 32.23 | 1.32 | 0.2721 | −1.42 |

| AD | 1.72 | 1 | 1.72 | 0.070 | 0.7951 | −0.33 |

| BC | 0.020 | 1 | 0.020 | 8.178E-4 | 0.9776 | 0.04 |

| BD | 359.40 | 1 | 359.40 | 14.67 | 0.0021 | −4.74 |

| CD | 60.63 | 1 | 60.63 | 2.47 | 0.1397 | −1.95 |

| Residuals | 318.51 | 13 | 24.50 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 299.05 | 10 | 29.91 | 4.61 | 0.1175 | |

| Pure error | 19.46 | 3 | 6.49 | |||

| Cor total | 3270.76 | 29 |

P < 0.05 is significant.

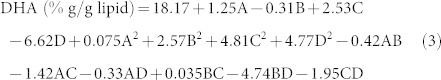

Final equation in terms of coded factors:

|

Final equation in terms of actual factors:

|

Medium optimization for enhanced lipid and DHA production

Software-based numerical optimization of the overall desirability function was performed to simultaneously determine the best possible goals for each response. The predicted optimal values for the variables were as follows: A = 60.00 g/L, B = 2.00 g/L, C = 24.00 g/L and D = 6.00 g/L. This combination was predicted to yield 9.49 g/L lipid with 41.06% DHA content. To examine the validity of this prediction, three successive experiments were performed using the predicted optimal medium. The average amount of lipid obtained in these experimental runs was 9.55 g/L with a DHA content of 44.07%. Overall, the absolute amount of DHA produced was 4.21 g/L, near to the predicted result of 3.90 g/L.

Scaling-up of DHA production

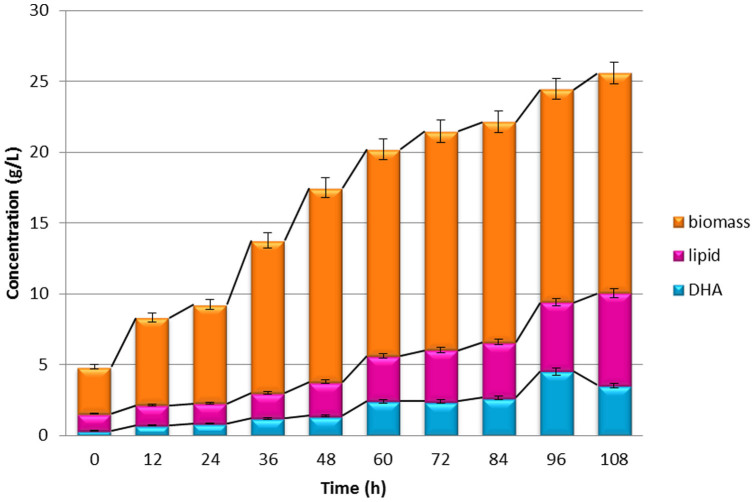

The optimized medium was used in a 5 L bench-top fermenter with a working volume of 3 L to assess its applicability and reproducibility on a larger scale. In this run, 9.40 g/L lipid was produced with a DHA content of 47.92%. Figure 1 shows the growth, lipid and DHA profiles of SW1 in this bioreactor run. The absolute amount of DHA accumulated was 4.50 g/L, close to that obtained in shake flask runs. This value is 25% higher than that produced in the original non-optimized medium.

Figure 1. Growth, lipid and DHA profiles of Aurantiochytrium sp. SW1 (grown in 5 L bench-top bioreactor at 30°C, agitation rate of 200 rpm and aeration rate of 1 vvm).

Discussion

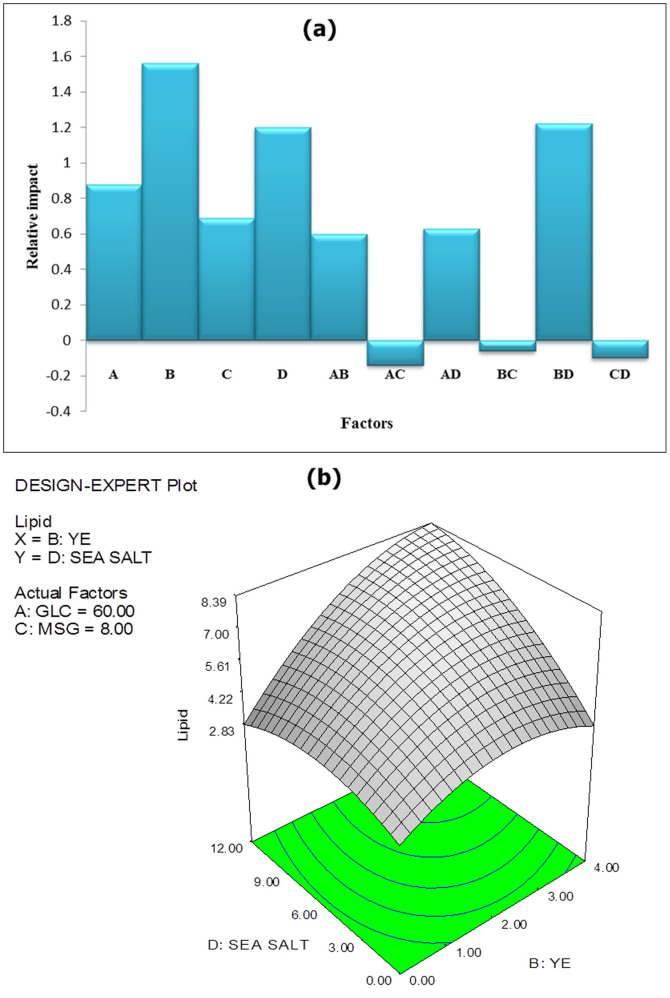

According to Anderson and Whitcomb22, the coefficients obtained in the final equation (in terms of coded factors) can be directly compared to assess the relative impact of factors. Figure 2a illustrates the relative effects of factors affecting the amount of lipid accumulated by SW1 via a bar graph. It can be concluded that the four significant factors, namely glucose (A), yeast extract (B), sea salt (D) and the interaction between yeast extract and sea salt (BD) have profound effects on lipid accumulation compared to other factors studied.

Figure 2. Graphs illustrating (a) relative effect of factors on lipid accumulation, and (b) effect of yeast extract-sea salt interaction on lipid accumulation.

It is well known that the amounts of carbon and nitrogen supply have profound effect on the amount of biomass produced. Apart from the carbon and nitrogen supply, the availability of trace minerals, particularly iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn), also affect the biomass production of thraustochytrids to a considerable extent23. In this study, although trace minerals are not supplied as separate components, sea salt serves as a source of the essential minerals required for optimal growth of SW1. The results of inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) showed that sea salt solution contains a vast variety of minerals. Table 3 lists the minerals found at concentrations above 0.05 mg/L in full strength sea salt solution (35 g sea salt/L).

Table 3. Mineral content of artificial sea water.

| Element | Concentration in sea salt solution (35 g/L sea salt) (mg/L) | Concentration in culture medium (6 g/L sea salt) (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Be 313.107 | 0.0814 | 0.0140 |

| Cd 228.802 | 0.0813 | 0.0139 |

| Ca 317.933 | 202.4837 | 34.7115 |

| Cr 267.716 | 0.0596 | 0.0102 |

| Co 228.616 | 0.0637 | 0.0109 |

| Cu 327.393 | 0.2538 | 0.0435 |

| Fe 238.204 | 0.0829 | 0.0142 |

| Li 670.784 | 0.1990 | 0.0341 |

| Mg 285.213 | 180.6768 | 30.9732 |

| Mn 257.610 | 0.0646 | 0.0111 |

| Mo 202.031 | 0.1618 | 0.0277 |

| Ni 231.604 | 0.0633 | 0.0109 |

| Sb 206.836 | 0.0519 | 0.0089 |

| Se 196.026 | 0.0707 | 0.0121 |

| Tl 190.801 | 0.0672 | 0.0115 |

| V 290.880 | 0.0734 | 0.0126 |

| Zn 206.200 | 0.1178 | 0.0202 |

Optimal cell growth consequently leads to high absolute amount of lipid (g/L) although in some cases, the relative amount of lipid accumulated per unit biomass (% g/g biomass) is not high. Thus, it is reasonable that the three aforementioned factors which best favor growth are statistically significant in affecting the absolute amount of lipid produced by SW1. Conversely, the highly significant interaction between yeast extract and sea salt might imply that SW1 has an absolute requirement for vitamins provided by yeast extract and minerals provided by sea salt to accumulate high amounts of lipid. The pattern of the effect of this interaction on lipid can be visualized using a three-dimensional response surface plot and corresponding contour plot, as shown in Figure 2b.

This type of graphical visualization allows the relationships between the experimental levels of each factor and the response to be investigated, and the type of interactions between test variables to be determined, which is necessary to establish the optimal medium components and culture conditions. The elliptical nature of the curves shown in Figure 2b (as opposed to circular shapes) indicates significant mutual interactions between the variables (yeast extract and sea salt)24. At low to moderate levels of yeast extract concentration, the lipid concentration is unaffected by increasing levels of sea salt. However, at high yeast extract concentrations, an increase in sea salt concentration leads to a significant increase in the amount of lipid. This indicates that the effect of sea salt on lipid is dependent on the levels of yeast extract provided.

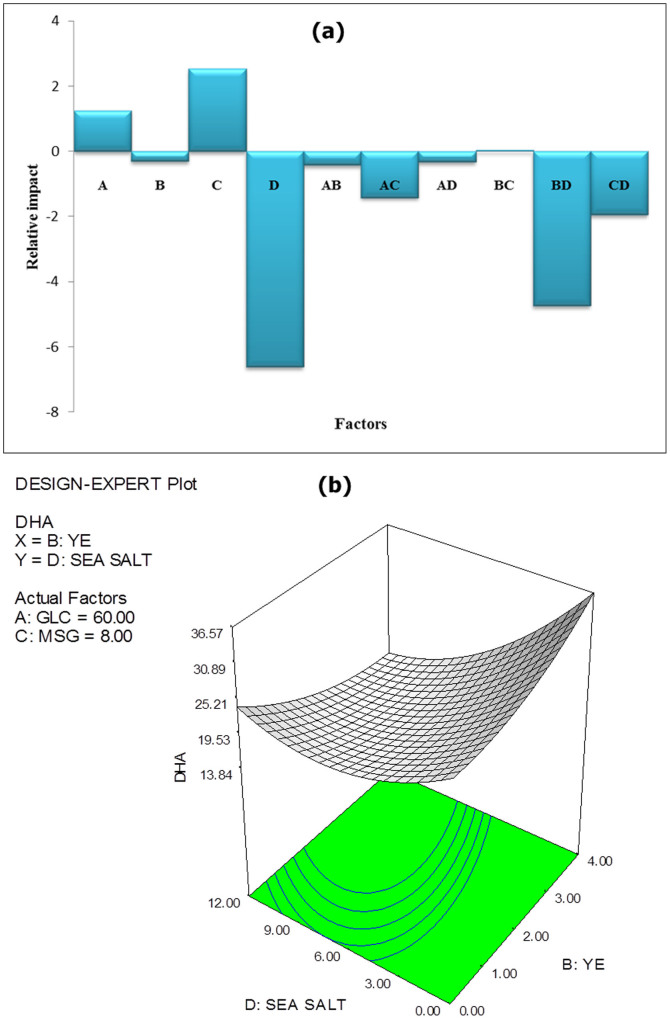

It is noteworthy that yeast extract, which has greatest influence on lipid accumulation, is not a significant factor for DHA accumulation. Notably, MSG, which had no significant effect on lipid, exerts considerable effect on DHA concentration. Similar results were reported by Burja et al.25, where they found that the addition of MSG to culture medium resulted in enhanced DHA production by Thraustochytrium sp. ONC-T18. In agreement with this study, Ren et al.26 reported that MSG positively influenced DHA accumulation in Schizochytrium sp. CCTCC M209059. Interestingly, in contrast to lipids, most factors exert negative effects on the percentage of DHA, whereas only glucose and MSG have positive effects (as shown in Figure 3a). This signifies that percentage of DHA accumulation is a subtle response, which requires very detailed and careful analyses to be optimized successfully.

Figure 3. Graphs illustrating (a) relative effect of factors on DHA content, and (b) effect of yeast extract-sea salt interaction on DHA content.

Similar to lipids, the percentage of DHA was significantly affected by the interaction of yeast extract with sea salt (BD). However, in contrast to its effect on lipids, this interaction affects DHA negatively, as indicated by a negative coefficient for this factor in the coded term equation. Figure 3b shows the three-dimensional response surface plot for this interaction. From this figure, it can be deduced that providing high levels of both yeast extract and sea salt simultaneously has a strong negative effect on DHA. Similarly, low levels of both components do not promote DHA accumulation. Thus, to obtain high amounts of DHA, either one of these factors must be kept at a low level while maintaining the other factor at high level.

To date, numerous studies have been conducted to enhance DHA production of thraustochytrids using various modes of fermentation and strategic techniques. Table 4 summarizes biomass production and DHA content of various thraustochytrid strains cultivated using glucose as major carbon source in bench-top bioreactors in comparison to SW1. Among the reports listed in this table, Aurantiochytrium sp. KRS101 is one of the strains that have been found to have a high genetic similarity (BLAST) and close phylogenetic relationship with SW1. In an attempt to enhance DHA production by this isolate, Hong et al.27 carried out the conventional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) optimization where final DHA concentration was successfully increased to 2.8 g/L from the initial concentration of ±2.0 g/L (5 L scale, 72 h). This is equivalent to a DHA production rate of 38.9 mg/L/h. In comparison, SW1 produced 4.5 g/L (5 L scale, 96 h), equivalent to 46.9 mg/L/h in the optimized medium formulated using the more sophisticated statistical design of experiments (DoE).

Table 4. Summary of biomass production and DHA content of various thraustochytrids in comparison to SW1 (YE: yeast extract, MSG: monosodium glutamate).

| Strain | Carbon source | Nitrogen source | % DHA/TFA | Biomass (g/L) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aurantiochytrium sp. KRS101* | Glucose | YE, NH4C2H3O2 | ±40 | ±33 | [27] |

| Aurantiochytrium sp. KRS101 | Glucose | YE, NH4C2H3O2 | ±34 | 24.8 | [27] |

| S. mangrovei G-13 | Glucose | YE, Peptone | 28 | 14 | [33] |

| Schizochytrium sp. SR21 | Glucose | (NH4)2SO4 | 33.3–38.6 | 21.9–59.2 | [34] |

| Schizochytrium sp. KH 105 | Glucose | Waste water from barley distillery | 25.8 | ±26 | [35] |

| Aurantiochytrium sp. SW1 | Glucose | YE, MSG | 47.9 | 24.5 | This study |

*fed-batch cultivation.

In conclusion, the production medium for enhanced DHA accumulation by Aurantiochytrium sp. SW1 was successfully optimized using response surface methodology (RSM). Simultaneous high yields of lipid (9.55 g/L) and DHA (44.07%) were obtained, resulting in a 17% increase in the final amount of DHA. Reproducible results were obtained when the culture was scaled-up to 5 L in a bench top bioreactor.

The isolate SW1 was previously known as Schizochytrium sp. SW1 based on its morphology and phylogenetic analysis. However, as described by Yokoyama & Honda (doi:10.1007/s10267-006-0362-0), the molecular phylogeny suggests that the genus Schizochytrium sensu lato is not a natural taxon. The first report of the polyphyly of Schizochytrium sensu lato by Honda et al (doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb05141.x) showed that members of this genus appeared in three distinct lineages. Yokoyama & Honda congregated these into three different genera: Schizochytrium sensu stricto, Aurantiochytrium and Oblongichytrium, based on their phenotypic characteristics as well as profiles of the PUFAs and carotenoid pigments. Based on these criteria, SW1 has been renamed as Aurantiochytrium SW1.

Methods

Microorganisms and culture conditions

Aurantiochytrium sp. SW1 (GenBank: KF500513) was obtained from the Microbial Physiology laboratory, School of Biosciences and Biotechnology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia and maintained at room temperature on seawater nutrient agar (SNA) slant which contained 28 g/L nutrient agar (Oxoid) and 17.5 g/L sea salt. Ten single colonies of a 48 hour old culture grown on SNA were transferred into 50 mL seeding broth (in 250 mL flasks) containing 60 g/L glucose (sterilized and added separately), 2 g/L yeast extract, 8 g/L monosodium glutamate (MSG) and 6 g/L sea salt25. The seed culture was then incubated for 48 hours with 200 rpm agitation at 30°C. A 10% v/v inoculum was inoculated into 50 mL production medium containing sea salt, glucose, yeast extract and MSG according to the levels set in the experimental design (Table 5). The cultures were incubated for 96 hours at 30°C with 200 rpm agitation.

Table 5. Experimental design for medium optimization.

| Run | A: Glucose | B: Yeast extract | C: MSG | D: Sea salt | Lipid (g/L) | DHA (% g/g lipid) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 12.00 | 9.51 | 18.66 |

| 2 | 40.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.24 | 39.63 |

| 3 | 40.00 | 4.00 | 16.00 | 12.00 | 5.09 | 26.68 |

| 4 | 40.00 | 0.00 | 16.00 | 0.00 | 2.14 | 41.48 |

| 5 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 6.00 | 4.92 | 16.86 |

| 6 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 6.00 | 6.44 | 21.11 |

| 7 | 80.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 28.80 |

| 8 | 80.00 | 4.00 | 16.00 | 0.00 | 2.24 | 48.58 |

| 9 | 40.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.00 | 1.19 | 26.30 |

| 10 | 80.00 | 0.00 | 16.00 | 12.00 | 1.15 | 27.67 |

| 11 | 80.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.27 | 44.20 |

| 12 | 80.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.00 | 0.81 | 33.14 |

| 13 | 40.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 12.00 | 4.80 | 16.65 |

| 14 | 40.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 19.98 |

| 15 | 80.00 | 0.00 | 16.00 | 0.00 | 0.73 | 37.24 |

| 16 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 6.00 | 6.59 | 16.31 |

| 17 | 40.00 | 0.00 | 16.00 | 12.00 | 1.96 | 24.87 |

| 18 | 40.00 | 4.00 | 16.00 | 0.00 | 2.68 | 44.22 |

| 19 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 6.00 | 6.35 | 17.40 |

| 20 | 80.00 | 4.00 | 16.00 | 12.00 | 9.63 | 23.29 |

| 21 | 60.00 | 6.00 | 8.00 | 6.00 | 5.43 | 19.13 |

| 22 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 24.00 | 6.00 | 9.21 | 39.03 |

| 23 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 6.00 | 7.47 | 16.46 |

| 24 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 2.51 | 48.42 |

| 25 | 60.00 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 6.00 | 0.84 | 34.05 |

| 26 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 18.00 | 6.07 | 22.36 |

| 27 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 3.21 | 32.04 |

| 28 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 6.00 | 7.54 | 20.89 |

| 29 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 6.00 | 2.89 | 14.54 |

| 30 | 100.00 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 6.00 | 10.41 | 18.66 |

Experimental design

Medium optimization was carried out using a CCD (RSM using Design Expert Version 6.0.10) with six center point replications. According to the CCD, the total number of experimental run was

|

where k is the number of independent variables and n0 is the number of center point replication28,29. The following equation was employed for statistical calculations:

|

where xi is the dimensionless coded value of the variable Xi, X0 is the value of the Xi at the center point and δX is the step change30. The behavior of the system was modeled using the following quadratic equation:

|

where Y is predicted response, β0 is the offset term, βi is the linear effect, βii is the squared effect and βij is the interaction effect31. The chosen ranges of factors are: glucose 40–80 g/L, yeast extract 0–4 g/L, MSG 0–16 g/L and sea salt 0–12 g/L. Table 5 shows the experimental design for medium optimization as well as the amount of lipid and DHA content obtained.

Fermentation scaling-up

Validated optimal levels of each parameter were employed in a scaling-up experiment carried out in a 5 L bench-top bioreactor (Minifors-Infors HT) with a working volume of 3 L. The culture temperature was controlled at 30°C and the impeller speed was fixed at 200 rpm. The aeration was controlled at 1 vvm. Samples were collected every 12 h for biomass, lipid and DHA determination.

Determination of dry cell weight

Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3500 rpm (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5810R) for 15 minutes followed by two rinses with 50 ml sterile distilled water. Samples were oven-dried at 95°C to constant weight. Biomass was expressed as oven-dried weight in gram per liter of growth medium.

Lipid extraction and fatty acid analysis

Lipid extraction was performed using chloroform-methanol (2:1, v/v), as described by Folch et al.32 The extract was vaporized at room temperature and dried in a vacuum desiccator until the weight was constant. Fatty acid compositions of the samples were determined as fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) by gas chromatography (HP 5890) equipped with a capillary column (BPX 70, 30 cm, 0.32 μm). FAME was prepared by dissolving 0.05 g of the sample in 0.95 mL hexane, and the mixture was added to 0.05 ml of 1 M sodium methoxide. The injector was maintained at 200°C. Then, 1 μl of sample was injected using helium as a carrier gas with a flow rate of 40 cm3min−1. The temperature of the GC column was gradually increased at 7°C min−1 from 50 (5 min hold) to 200°C (10 min hold). Fatty acids peaks were identified using Chromeleon chromatography software (Dionex, Sunnyvale, California, USA). FAMEs were identified and quantified by comparison with the retention time and peak areas of SUPELCO (Bellefonte, PA, USA).

Author Contributions

V.M. designed and performed the experiments, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript, M.S.K. conceived of the study, participated in its design and helped to draft the manuscript, A.A.H. conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, supervised all experimental procedures and helped to draft the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia for funding this research under the Exploratory Research Grant Scheme – ERGS/1/2012/STG08/UKM/02/15.

References

- Kris-Etherton P. M., Harris W. S. & Appel L. J. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 106, 2747–2757 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole G. M. et al. Prevention of Alzheimer's disease: Omega-3 fatty acid and phenolic anti-oxidant interventions. Neurobiol. Aging. Suppl 1, 133–136 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins D. A. et al. Alternative sources of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in marine microalgae. Mar. Drugs 11, 2259–2281 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward O. P. & Singh A. Omega-3/6 fatty acids: Alternative sources of production. Process Biochem. 40, 3627–3652 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Gerber L. R., Karimi R. & Fitzgerald T. P. Sustaining seafood for public health. Front. Ecol. Environ. 10, 487–493 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Larcombe J. & Begg G. A. (Eds.). Fishery status reports 2007: status of fish stocks managed by the Australian Government. Bureau of Rural Sciences (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Worm B. et al. Impacts of biodiversity loss on ocean ecosystem services. Science 314, 787–790 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K. J. L. et al. Biodiscovery of new Australian thraustochytrids for production of biodiesel and long-chain omega-3 oils. Appl. Microbol. Biotechnol. 93, 2215–2231 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokochi T., Honda D., Higashihara T. & Nakahara T. Optimization of docosahexaenoic acid production by Schizochytrium limacinum SR21. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 49, 72–76 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T., Allsopp M. T. E. P. & Chao E. E. Thraustochytrids are chromists, not fungi: 18S rRNA signature of Heterokonta. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 346, 387–397 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Leipe D. D. et al. The straminopiles from a molecular perspective: 16S-like rRNA sequences from Labirinthuloides minuta and Cafeteria roenbergensis. Phycologia 33, 369–377 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Honda D. et al. Molecular phylogeny of labirunthulids and thraustochytrids based on sequence of 18S ribosomal RNA gene. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 46, 637–647 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasuja N. D., Jain S. & Joshi S. C. Microbial production of docosahexaenoic acid (Ω-3 pufa) and their role in human health. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 3, 83–87 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara T. et al. Production of docosahexaenoic and decosapentaenoic acids by Schizochytrium sp. isolated from Yap islands. JAOCS 73, 1421–1426 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Raghukumar S. Morphology, taxonomy and ecology of thraustochytrids and labyrinthulids, the marine counterpart of zoosporic fungi,. in: Dayal R., (Ed.), Advances in Zoosporic Fungi. Publications Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi, pp. 35–60 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H., Fukuba T. & Naganuma T. Biomass of thraustochytrid protoctists in coastal water. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 189, 27–33 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T. E., Nichols P. D. & McMeekin T. A. The biotechnological potential of thraustochytrids. Mar. Biotechnol. 1, 580–587 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay W., Weaver C. & Metz J. Development of a DHA production technology using Schizochytrium: a historical perspective,. in: Cohen Z., & Ratledge C., (Eds.), Single Cell Oils. AOCS Press. Illinois, pp. 75–96 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Fan L. H. et al. Optimization of carbon dioxide fixation by Chlorella vulgaris cultivation in a membrane-photobioreactor. Chem. Eng. Technol. 30, 1094–1099 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Gomathi V., Saravanakumar K. & Kathiresan K. Production of polyunsaturated fatty acid (DHA) by mangrove-derived Aplanochytrium sp. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 7, 1098–1103 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Manikan V., Kalil M. S., Isa M. H. M. & Hamid A. A. Improved prediction for medium optimization using factorial screening for docosahexaenoic acid production by Schizochytrium sp. SW1. Am. J. Applied Sci. 11, 462–474 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. & Whitcomb P. DOE Simplified: Practical Tools for Effective Experimentation, 2nd ed. Productivity Press, Boca Raton(2007). [Google Scholar]

- Nagano N., Taoka Y., Honda D. & Hayashi M. Effect of trace elements on growth of marine eukaryotes, tharaustochytrids. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 116, 337–339 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. H., Lou W. Y., Zong M. H. & Smith T. J. Optimization of culture conditions to produce high yields of active Acetobacter sp. CCTCC M209061 cells for anti-prelog reduction of prochiral ketones. BMC Biotechnol. 11, 110–121 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burja A. M., Radianingtyas H., Windust A. & Barrow C. J. Isolation and characterization of polyunsaturated fatty acid producing Thraustochytrium species: screening of strains and optimization of omega-3 production. App. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 72, 1161–1169 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren L. J., Li J., Hu Y. W., Ji X. J. & Huang H. Utilization of cane molasses for docosahexaenoic acid production by Schizochytrium sp. CCTCC M209059. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 30, 787–789 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Hong W. K. et al. Production of lipids containing high levels of docosahexaenoic acid by a newly isolated microalga, Aurantiochytrium sp. KRS101. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 164, 1468–1480 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal P. & Chandra T. S. Statistical optimization of medium components for enhanced riboflavin production by a UV-mutant of Eremothecium ashbyii. Proc. Biochem. 36, 31–37 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y. H., Liu J. Z., Song H. Y. & Ji L. N. Enhanced production of extracellular ribonuclease from Aspergillus niger by optimization of culture conditions using response surface methodology. Biochem. Eng. J. 21, 27–32 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa A. Importance of DHA in organisms. Pros. Puslitbangkan 18, 62–70 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa A. Effects of docosahexaenoic acid and phospholipids on stress tolerance of fish. Aquaculture 255, 129–134 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Folch J., Lees M. & Sloane Stanley G. H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497–509 (1957). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles R. D., Hunt A. E., Bremer G. B., Duchars M. G. & Eaton R. A. Long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid production by members of the marine protistan group the thraustochytrids: screening the isolates and optimisation of DHA production. J. Biotechnol. 70, 193–202 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Yaguchi T., Tanaka S., Yokochi T., Nakahara T. & Higashihara T. Production of high yields of docosahexaenoic acid by Schizochytrium sp. strain SR21. JAOCS 74, 1431–4 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki T. et al. Utilization of Shochu distillery wastewater for production of polyunsaturated fatty acids and xanthophylls using thraustochytrid. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 102, 323–7 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]