Abstract

Objectives

Prostate cancer mortality (PCM) in the USA is among the lowest in the world, whereas PCM in England is among the highest in Europe. This paper aims to assess the association of variation in use of definitive therapy on risk-adjusted PCM in England as compared with the USA.

Design

Observational study.

Setting

Cancer registry data from England and the USA.

Participants

Men diagnosed with non-metastatic prostate cancer (PCa) in England and the USA between 2004 and 2008.

Outcome measures

Competing-risks survival analyses to estimate subhazard ratios (SHR) of PCM adjusted for age, ethnicity, year of diagnosis, Gleason score (GS) and clinical tumour (cT) stage.

Results

222 163 men were eligible for inclusion. Compared with American patients, English patients were more likely to present at an older age (70–79 years: England 44.2%, USA 29.3%, p<0.001), with higher tumour stage (cT3-T4: England 25.1%, USA 8.6%, p<0.001) and higher GS (GS 8–10: England 20.7%, USA 11.2%, p<0.001). They were also less likely to receive definitive therapy (England 38%, USA 77%, p<0.001).

English patients were more likely to die of PCa (SHR=1.9, 95% CI 1.7 to 2.0, p<0.001). However, this difference was no longer statistically significant when also adjusted for use of definitive therapy (SHR=1.0, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.1, p=0.3).

Conclusions

Risk-adjusted PCM is significantly higher in England compared with the USA. This difference may be explained by less frequent use of definitive therapy in England.

Keywords: Prostate disease < UROLOGY, Urological tumours < UROLOGY, Adult oncology < ONCOLOGY, Health policy < HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A key strength of this paper is the use of routinely collected data from hospital episode statistics linked to cancer registry data, providing a large data set to make accurate estimates of relative prostate cancer mortality.

Lack of prostate-specific antigen data and a relatively short follow-up period of 6 years are the key limitations of this study.

Given that this is an observational study, there is some uncertainty about the causes for the observed differences in prostate cancer mortality.

Background

Outcomes following a diagnosis of cancer vary markedly around the world. In the USA, cancer-related deaths have been demonstrated to be among the lowest. For example, US breast cancer mortality is 65% lower than the European average while death from colorectal cancer is 30% lower.1 On the other hand, cancer mortality rates in England are among the highest in Europe.2 The disparity in cancer outcomes appears greatest for prostate cancer (PCa) for which 5-year mortality has been reported to be six times higher in England compared with the USA.1

A number of disease and treatment-related factors may account for the observed variation in PCa outcomes between the USA and England. These include variation in policy concerning PCa screening between the two countries together with variation in use of definitive PCa therapy. Other factors that may be at play include the methods by which data on cancer diagnoses and cancer-related deaths are both collected and processed.

In the USA, the vast majority of men diagnosed with localised PCa have definitive therapy, either by radical radiation therapy or radical surgery. For example, three-quarters of men diagnosed with PCa between 1988 and 2006 were reported to have undergone definitive therapy for their disease.3 This figure compares to only about one-third in England.4 5

We report differences in risk-adjusted prostate cancer mortality (PCM) between the USA and England. Furthermore, we investigate whether PCa outcomes are related to the use of definitive therapy between the two countries. This study is part of a programme of work assessing the value of procedure-specific and disease-specific metrics derived from English hospital admission records to assess the performance of English National Health Service (NHS) providers.

Methods

Study design

We performed a population-based observational cohort study using patient-level cancer registry data from England and the USA.

Data sources

Data collected by the eight regional cancer registries6 for all men diagnosed with PCa in England were linked to the Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) database7 and national mortality records provided by the Office for National Statistics.

The Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database was used to identify American patients with PCa from 18 regional cancer registries.8 This database covers 28% of the US population and is linked to mortality data provided by the National Center for Health Statistics.

Participants

Men diagnosed with PCa between 2004 and 2008, and aged between 35 and 80 years at the time of diagnosis were identified from both countries. The years 2004–2008 were selected as comparable English, and American data were available for this period. Diagnosis of PCa was confirmed using the ‘C61’ International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) diagnosis code in the HES and SEER databases. Follow-up data were available through to 16 April 2010 for the English cohort, and 31 December 2010 for the American cohort.

Patients were included if PCa was histologically confirmed as their only primary malignancy. Patients with lymph node involvement or distant metastases were excluded, as they would not be candidates for primary definitive therapy. Where data on metastatic disease were missing, we considered the use of chemotherapy as a surrogate marker for metastases. Patients who underwent chemotherapy within 6 months of diagnosis were therefore also excluded. Twenty-one patients in the English data set were noted to have negative survival data (ie, date of diagnosis was chronologically after the date of death), and were therefore excluded. Those with missing data concerning pathological Gleason score (GS) or clinical tumour (cT) stage were excluded from the primary analysis, as they would not be amenable to risk stratification.

Variable definition

English patients were considered to have undergone definitive therapy if their HES record contained the ‘M61’ Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures (4th revision) code9 indicating radical prostatectomy within 1 year of diagnosis, or alternatively if their cancer registry record indicated the use of radiotherapy.

Patients from the SEER data set were considered to have undergone definitive therapy if they underwent radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy as part of their first course of therapy. American patients were considered to have undergone radical prostatectomy if they had undergone cancer-directed surgery, coded as any of the following: radical/total prostatectomy, or prostatectomy with resection in continuity with other organs/pelvic exenteration. All forms of radiotherapy were assumed to be definitive in nature, as treatment doses are not routinely recorded in the SEER or English cancer registries.

Risk stratification

Patients were classified into risk groups using a modified version of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) PCa risk classification,10 based on cT stage and GS. Risk groups were defined as follows: low risk (cT1 stage and GS 2–6), intermediate risk (cT2 stage or GS 7), and high risk (cT3-T4 stage or GS 8–10). Since prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels are not recorded in the HES database or English cancer registries, this variable was not used for risk stratification in this study.

Outcome measurement

The cause of death among English patients was extracted from national mortality records provided by the Office for National Statistics, which were linked to cancer registry and HES data. Similarly, cause of death is routinely recorded as part of the SEER data set for US patients. Where the cause of death was listed as the disease code for PCa, C61, it was classified as a PCa death.

Statistical analysis

χ2 test was used to compare proportions between the two countries. A Cox regression model was used to calculate adjusted HRs for all-cause mortality (ACM), comparing mortality in England and the USA. Similarly, adjusted subhazard ratios (SHR) were calculated for PCM using a maximum likelihood competing risk regression model, according to the method of Fine and Gray.11 Failure event for PCM was defined as death due to PCa, while death due to a cause other than PCa was defined as the competing event. All analyses were performed using STATA V.11 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

All regression models were adjusted for age group, year of diagnosis, ethnicity, cT stage and GS (model 1). Next, the impact of variation in use of definitive therapy was assessed by additionally including use of definitive therapy in a separate regression model (model 2). Separate regression models were built to test for differences between the two countries for each individual risk group. This resulted in 20 regression models in total: 5 patient groups (all eligible patients, all patients with complete data, low, intermediate and high risk)×2 adjustment models (model 1 and model 2)×2 outcomes (ACM and PCM).

Sensitivity analysis

In order to investigate the influence of excluding patients for whom tumour stage and Gleason grade data were missing, we performed a sensitivity analysis where all eligible patients were included.

Role of funding source

The study benefited from a grant from the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges supporting a project assessing the value of procedure-specific and disease-specific metrics derived from routinely collected data to assess the performance of NHS providers. Sponsors were not involved in the study design; the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results

Participants

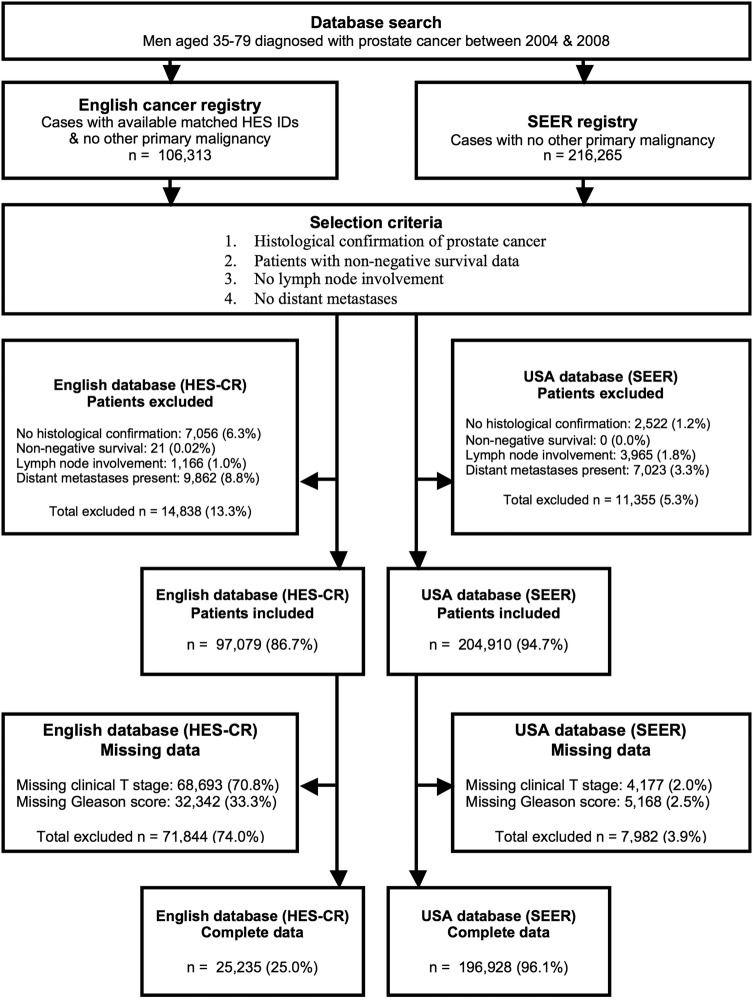

Data were available on 328 182 men (111 917 from England and 216 265 from the USA) of which 301 989 (97 079 from England and 204 910 from the USA) met the selection criteria. Reasons for exclusion are described in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram (HES, Hospital Episodes Statistics; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results).

Complete data to enable risk stratification (ie, cT stage and GS) were available for 222 163 men (23 235 from England and 196 928 from the USA). These data were used to undertake the primary analysis.

Men diagnosed with PCa in England tended to be older and less ethnically diverse, to present with higher cT stage, and to have higher pathological GSs (table 1, see online supplementary appendix 1), with each of these differences reaching statistical significance at p<0.001. Among patients for whom complete data were available, men diagnosed with PCa in England were more likely to present with high-risk PCa according to our modified NCCN criteria (34.5% in England and 17.2% in USA, table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics by country (n=222 163)

| England | USA | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=25 235) | (n=196 928) | ||

| Year of diagnosis (%) | |||

| 2004 | 5378 (21.3) | 36 172 (18.4) | <0.001 |

| 2005 | 4959 (19.7) | 34 403 (17.5) | |

| 2006 | 5172 (20.5) | 40 531 (20.6) | |

| 2007 | 5009 (19.9) | 43 800 (22.2) | |

| 2008 | 4717 (18.7) | 42 022 (21.3) | |

| Age group (%) | |||

| 35–59 | 3620 (14.4) | 56 399 (28.6) | <0.001 |

| 60–64 | 4361 (17.3) | 40 287 (20.5) | |

| 65–69 | 6104 (24.2) | 42 439 (21.6) | |

| 70–74 | 6145 (24.4) | 33 912 (17.2) | |

| 75–79 | 5005 (19.8) | 23 891 (12.1) | |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||

| White | 17 924 (94.8) | 154 077 (80.4) | <0.001 |

| African/Caribbean | 571 (3.0) | 28 361 (14.8) | |

| Asian | 318 (1.7) | 8638 (4.5) | |

| Other | 105 (0.6) | 626 (0.3) | |

| Missing | 6317 | 5226 | |

| cT stage (%) | |||

| cT1 | 9374 (37.2) | 72 407 (36.8) | <0.001 |

| cT2 | 9538 (37.8) | 107 762 (54.7) | |

| cT3 | 5577 (22.1) | 15 482 (7.9) | |

| cT4 | 746 (3.0) | 1277 (0.7) | |

| Gleason score (%) | |||

| 2–6 | 10 909 (43.2) | 99 661 (50.6) | <0.001 |

| 7 | 9112 (36.1) | 75 247 (38.2) | |

| 8–10 | 5214 (20.7) | 22 020 (11.2) | |

| Modified NCCN risk (%) | |||

| Low risk | 6151 (24.4) | 45 045 (22.9) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate risk | 10 386 (41.2) | 118 074 (60.0) | |

| High risk | 8698 (34.5) | 33 809 (17.1) | |

| Treatment—all risk groups (%) | |||

| No definitive therapy | 15 583 (61.8) | 45 113 (22.9) | <0.001 |

| Definitive therapy | 9652 (38.2) | 151 815 (77.1) | |

| Treatment—low risk (%) | |||

| No definitive therapy | 3799 (61.8) | 17 516 (38.9) | <0.001 |

| Definitive therapy | 2352 (38.2) | 27 529 (61.1) | |

| Treatment—intermediate risk (%) | |||

| No definitive therapy | 5696 (54.8) | 21 999 (18.6) | <0.001 |

| Definitive therapy | 4690 (45.2) | 96 075 (81.4) | |

| Treatment—high risk (%) | |||

| No definitive therapy | 6088 (70.0) | 5598 (16.6) | <0.001 |

| Definitive therapy | 2610 (30.0) | 28 211 (83.4) | |

cT, clinical tumour; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Men diagnosed with PCa in England were less likely to receive definitive therapy (38.2% in England and 77.1% in USA), and this difference was observed in all risk groups (table 1).

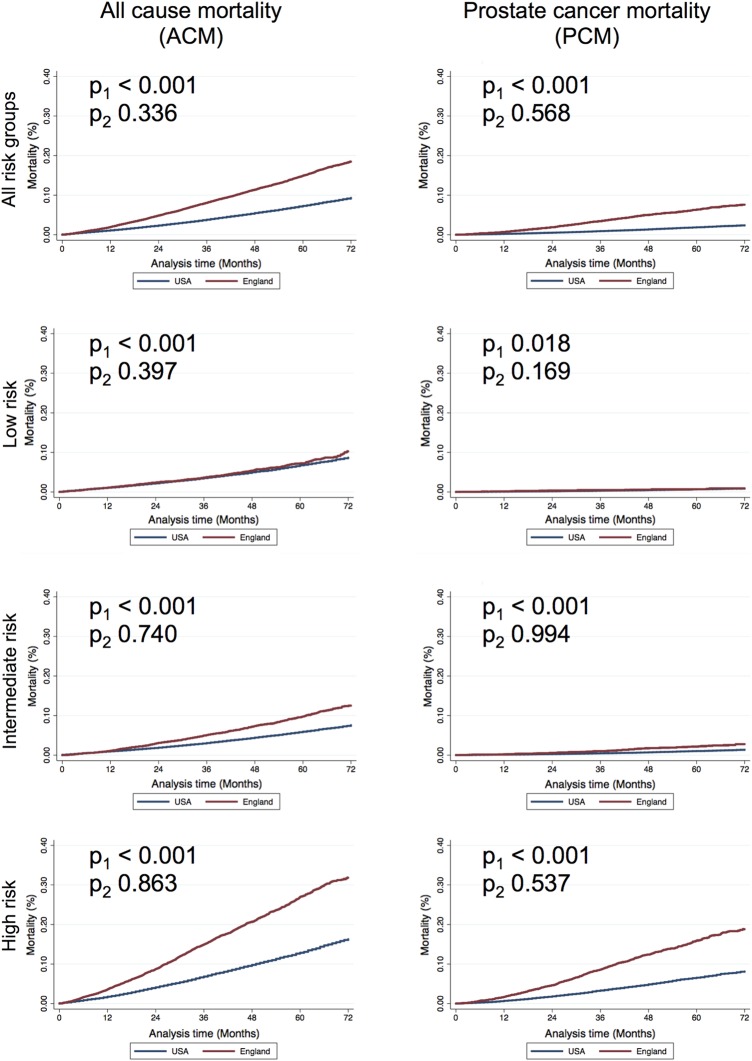

Mortality

The median follow-up for the entire cohort was 43.3 months. Unadjusted 6-year ACM among English men was higher compared with American men (21.0% vs 9.6%). Similarly, unadjusted 6-year PCM among English men was also higher, as compared with American men (9.6% vs 2.6%). This trend was similar among patients with complete data, whose outcomes are described below (table 2 and figure 2).

Table 2.

ACM and PCM according to country of treatment and modified NCCN risk (n=222 163)

| 6-year ACM |

Model 1 (age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, ethnicity, clinical tumour stage and Gleason score) |

Model 2 (model 1 and definitive therapy) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk group | USA | England | Adj HR (95% CI) | p Value | Adj HR (95% CI) | p Value |

| n=196 928 | n=25 235 | |||||

| All risk groups | 9.3% | 18.5% | 1.60 (1.52 to 1.68) | <0.001 | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.08) | 0.336 |

| Low risk | 8.7% | 10.3% | 1.30 (1.15 to 1.48) | <0.001 | 1.06 (0.93 to 1.21) | 0.397 |

| Intermediate risk | 7.6% | 12.5% | 1.44 (1.32 to 1.58) | <0.001 | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.08) | 0.740 |

| High risk | 16.3% | 31.8% | 1.92 (1.78 to 2.06) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.08) | 0.863 |

| 6-year PCM |

Model 1 (age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, ethnicity, clinical tumour stage and Gleason score) |

Model 2 (model 1 and definitive therapy) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk group | USA | England | Adj SHR (95% CI) | p Value | Adj SHR (95% CI) | p Value |

| All risk groups | 2.4% | 7.6% | 1.88 (1.72 to 2.05) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.88 to 1.07) | 0.568 |

| Low risk | 0.9% | 0.9% | 1.57 (1.08 to 2.30) | 0.018 | 1.31 (0.89 to 1.93) | 0.169 |

| Intermediate risk | 1.4% | 2.8% | 1.71 (1.40 to 2.09) | <0.001 | 1.00 (0.81 to 1.23) | 0.994 |

| High risk | 8.1% | 18.8% | 2.06 (1.87 to 2.28) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.86 to 1.08) | 0.537 |

ACM, all-cause mortality; Adj HR, adjusted HR; Adj SHR, adjusted subhazard ratios; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; PCM, prostate cancer mortality.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier plots for all-cause mortality (ACM) and prostate cancer mortality (PCM). Separate p values are reported for regression models with (model 1, p1) and without (model 2, p2) the inclusion of definitive therapy.

Primary analysis

The primary analysis was conducted using data from the 222 163 patients for whom cT stage and GS were available, to allow risk stratification.

Unadjusted 6-year ACM among patients who had definitive therapy was 7.3% in England and 4.9% in the USA. Corresponding ACM figures among those who did not have definitive treatment were 19.5% in England and 15.5% in the USA. The greatest difference was observed in patients at high PCa risk undergoing definitive treatment with a 6-year ACM of 15.1% in England and 8.1% in the USA, with the smallest difference observed in patients with low-risk PCa who did not undergo definitive therapy (9.5% in England and 9.9% in the USA).

Unadjusted 6-year PCM among patients from all risk groups who underwent definitive therapy was 2.4% in England and 1.2% in the USA. This compared with 8.8% among patients who did not receive definitive therapy in England and 4.5% in the USA. Differences in unadjusted 6-year PCM were smallest among patients with low-risk disease undergoing definitive therapy (0.4% in England and 0.5% in the USA), and greatest among patients with high-risk disease undergoing definitive therapy (7.6% in England and 3.7% in the USA).

When comparing all patients with complete data amenable for risk stratification, following adjustment for age group, ethnicity, year of diagnosis and tumour characteristics (model 1), significantly higher ACM (adjusted HR=1.60, 95% CI 1.52 to 1.68) and PCM (adjusted SHR=1.88, 95% CI 1.72 to 2.05) were found in England than in the USA (table 2). Within each of the three risk groups, with adjustment for patient and tumour characteristics (model 1), the greatest difference in ACM and PCM was noted among the intermediate-risk and high-risk patients (table 2). PCM was not significantly different at 0.9% in both countries at 6 years among men with low-risk disease.

When treatment allocation was included in the multivariate model (model 2), no difference in ACM and PCM was noted between the USA and England for all men (ACM: adjusted HR=1.03, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.08; PCM: adjusted SHR=0.97, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.07) or within each of the individual risk groups (table 2).

Sensitivity analysis

Multivariate analysis for the entire cohort of 301 989 patients, including patients for whom data regarding either cT stage or GS were missing, revealed a similar trend (see online supplementary appendix 2). Adjustment for age group, ethnicity and year of diagnosis revealed higher ACM (adjusted HR=2.19, 95% CI 2.13 to 2.26) and PCM (adjusted SHR=3.67, 95% CI 3.50 to 3.85) among English patients.

Additional adjustment for the use of definitive therapy appeared, in part, to account for variation in ACM (adjusted HR=1.55, 95% CI 1.50 to 1.59) and PCM (adjusted HR=2.37, 95% CI 2.25 to 2.50).

Discussion

PCa death in intermediate to high-risk cases is higher in England than it is in the USA. When we adjusted for the different rates of definitive therapy in the two countries, the rates of PCa death were similar. This suggests that the differences in mortality may be explained by a lower use of definitive therapy in England.

Methodological considerations

First, the English data set contained a high proportion of missing data for cT stage and GS. The high proportion of patients with missing data in the English data set may be due to poor data capture. Excluded English patients tended to be older, to have more advanced disease, and they less frequently received definitive therapy (see online supplementary appendix 3). This limitation is unlikely to have had a marked influence on our results, as inclusion of these patients would have increased the observed difference in PCM noted between the two countries. Thus, these data provide a conservative estimate of the spread of PCa risk among the general English population. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to note that these are the only population-wide data currently available for comparing management of PCa in the two countries.

Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis was performed to investigate the influence of excluding patients with missing cT stage or GS. This showed that PCM is significantly higher in England than the USA, though this difference is partly explained on additional adjustment for the variation in use of definitive treatment in the two countries. Owing to the higher proportion of men with low-risk or intermediate-risk disease in the USA, the variation in use of definitive treatment becomes more apparent on risk stratification in our primary analysis.

Second, the SEER data set did not contain information concerning patient comorbidity. We feel our findings remain valid despite this potential limitation as PCM is less strongly influenced by comorbid conditions than ACM.12 In addition, there were also differences between England and the USA in the PCM of young patients aged between 35 and 59 years who are least likely to have comorbid conditions at the time of diagnosis (adjusted SHR=2.66, 95% CI 1.99 to 3.56, p<0.001).

Third, ‘lead time bias’ could be an explanation for PCM being lower in the USA than in the UK given that the uptake of PSA testing is much higher in the USA, the effect of which is likely to be that men in the USA are diagnosed with less advanced PCa at an earlier age. In an attempt to minimise the effect of this limitation, we adjusted for clinical stage at diagnosis and patient age at diagnosis together with GS in our primary analysis.

Lastly, PSA levels were not available for English patients, and therefore they could not be used to adjust the differences in PCM between England and the USA. To investigate this limitation further, we evaluated if the inclusion of PSA into our risk stratification model resulted in significant recategorisation of a patient's PCa risk for the US patients. We found little movement between risk groups with, for example, only 7.4% US patients being reclassified as intermediate-risk having initially been assigned a low-risk status. Furthermore, Elliott et al13 have previously shown that while it is advantageous to have all three clinical variables (including PSA, cT stage and GS) available for risk stratification, patients with high-risk disease can still be correctly identified even if one of these variable (such as PSA) is missing.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, routinely collected data provide a rich resource to explain performance of healthcare providers in different countries. However, differences in coding practices and differences in healthcare frameworks must be acknowledged.

Comparison with other studies

Mortality

PCM was found to be significantly higher in England compared with the USA among men with intermediate-risk and high-risk PCa. In the current study, we used SEER data of men diagnosed between 2004 and 2008 and found that 6-year ACM was 9.3% and PCM 2.4%. A study using SEER data of men diagnosed between 1992 and 2005 found very similar figures (5-year ACM 14.3% and PCM 1.7%).14 Improvements in management of PCa and other comorbidities may explain why our figures for ACM are slightly lower.

In comparison, our analysis of the English HES database found that 6-year ACM was 18.5% and PCM 7.6%. A study reporting outcome of 50 066 men diagnosed with PCa in the London area between 1997 and 2006 with a median follow-up of 3.5 years reported a PCM for men who had undergone definitive treatment of about 2%, which corresponds closely to the figures we found in this study.15

The only two relevant randomised controlled trials16 17 demonstrated benefit of definitive therapy in patients with high-risk disease, which is consistent with the results of our study.

Differences between England and the USA

A study using the EUROCARE and SEER registries including men diagnosed between 1985 and 1989 reported a 2.8 times relative excess risk of death among European men with PCa compared with their American counterparts.18 A recent study using SEER data between 1975 and 2004 together with UK cancer mortality statistics found that age-adjusted PCM rates in the USA were significantly lower than in England with the decline in PCM being 4.2% per year since the 1990s, a figure about four times higher than that reported for England.19

The investigators of both these studies suggested that difference in PCM between England and the USA is the result of variation in disease burden brought about by the higher incidence of PCa screening in the USA. However, neither study adjusted for PCa risk. In this study, we have identified for the first time that irrespective of PCa stage and GS, PCa outcomes in terms of ACM and PCM are better in the USA than in England, which does not support the increased use of PCa screening in the USA as an explanation for the difference in PCM. Instead, our data suggest that the better PCa outcome seen in the USA may be due to the more frequent use of definitive treatment.

Clinical implication

The decision to offer definitive PCa therapy is influenced by both disease characteristics and patient characteristics. As noted in our results, variations in healthcare systems have direct and indirect effects on both these factors. The expected survival benefit of definitive PCa therapy must therefore also be balanced against the associated probability of side effects, including urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction.

Our analysis suggests that PCM in England may be improved by an increase in the use of definitive treatment. However, due to the retrospective nature of this analysis, there could be other factors such as lead time bias which account for this difference. Only randomised trials can address these differences directly.

Acknowledgments

AS has received funding from the Isaac Shapera Trust for Medical Research, and is currently funded by a National Institute of Health Research Academic Clinical Fellowship. ME receives research support from the UK National Institute of Health Research University College London/University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre. PJC receives funding from The Orchid Charity and Barts & The London Charity.

Footnotes

Contributors: AS, JHvdM and PJC were involved in the study design. AS prepared and analysed the data. JHvdM advised on statistical issues and data presentation. All authors were involved in data interpretation. AS and PJC drafted the report. All authors revised the report critically for intellectually important content, and approved the final version to be published. AS and PJC had full access to all of the data and are guarantors.

Funding: Isaac Shapera Trust for Medical Research, The Orchid Charity, Academy of Medical Royal Colleges.

Competing interests: ME has received funding from GSK, Sonacare, STEBA Biotech and Sanofi-Aventis, outside the submitted work. He acts as a consultant to these companies and has received honoraria for speaking and organising and participating in educational activities. JHvdM has received a 1-year unrestricted research grant from Sanofi-Aventis, outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Coleman MP, Quaresma M, Berrino F et al. . Cancer survival in five continents: a worldwide population-based study (CONCORD). Lancet Oncol 2008;9:730–56. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70179-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP et al. . Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE-5—a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:23–34. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70546-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdollah F, Sun M, Thuret R et al. . A competing-risks analysis of survival after alternative treatment modalities for prostate cancer patients: 1988–2006. Eur Urol 2011;59:88–95. 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fairley L, Baker M, Whiteway J et al. . Trends in non-metastatic prostate cancer management in the Northern and Yorkshire region of England, 2000–2006. Br J Cancer 2009;101:1839–45. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyratzopoulos G, Barbiere JM, Greenberg DC et al. . Population based time trends and socioeconomic variation in use of radiotherapy and radical surgery for prostate cancer in a UK region: continuous survey. BMJ 2010;340:c1928 10.1136/bmj.c1928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Cancer Data Repository 1990–2010. National Cancer Intelligence Network; [cited 2014 October 1]. http://www.ncin.org.uk/collecting_and_using_data/national_cancer_data_repository/

- 7.Hospital Episode Statistics. [Website]: NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre; [cited 2014 October 1]. http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/

- 8.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program 1975–2010. [Website] Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; [cited 2014 October 1]. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/

- 9.NHS Connecting for Health. Office of Population, Censuses, and Surveys (OPCS) Classification of Interventions and Procedures Version 4.6 (April 2011): The Stationery Office.

- 10.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Prostate Cancer. National Comprehensive Care Network; 2014 [cited 2014 October 1]. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf

- 11.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509. 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briganti A, Spahn M, Joniau S et al. . Impact of age and comorbidities on long-term survival of patients with high-risk prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy: a multi-institutional competing-risks analysis. Eur Urol 2013;63:693–701. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.08.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott SP, Johnson DP, Jarosek SL et al. . Bias due to missing SEER data in D'Amico risk stratification of prostate cancer. J Urol 2012;187:2026–31. 10.1016/j.juro.2012.01.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdollah F, Sun M, Schmitges J et al. . Cancer-specific and other-cause mortality after radical prostatectomy versus observation in patients with prostate cancer: competing-risks analysis of a large North American population-based cohort. Eur Urol 2011;60:920–30. 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chowdhury S, Robinson D, Cahill D et al. . Causes of death in men with prostate cancer: an analysis of 50,000 men from the Thames Cancer Registry. BJU Int 2013;112:182–9. 10.1111/bju.12212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Ruutu M et al. . Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1708–17. 10.1056/NEJMoa1011967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilt TJ, Brawer MK, Jones KM et al. . Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:203–13. 10.1056/NEJMoa1113162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Coleman MP et al. . Toward a comparison of survival in American and European cancer patients. Cancer 2000;89:893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collin SM, Martin RM, Metcalfe C et al. . Prostate-cancer mortality in the USA and UK in 1975–2004: an ecological study. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:445–52. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70104-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]