Abstract

Objectives

A recent study reported a large increase in the number of meniscal procedures from 2000 to 2011 in Denmark. We examined the nation-wide distribution of meniscal procedures performed in the private and public sector in Denmark since different incentives may be present and the use of these procedures may differ from region to region.

Setting

We included data on all patients who underwent an arthroscopic meniscal procedure performed in the public or private sector in Denmark.

Participants

Data were retrieved from the Danish National Patient Register on patients who underwent arthroscopic meniscus surgery as a primary or secondary procedure in the years 2000 to 2011. Hospital identification codes enabled linkage of performed procedures to specific hospitals.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Yearly incidence of meniscal procedures per 100 000 inhabitants was calculated with 95% CIs for public and private procedures for each region.

Results

Incidence of meniscal procedures increased at private and at public hospitals. The private sector accounted for the largest relative and absolute increase, rising from an incidence of 1 in 2000 to 98 in 2011. In 2011, the incidence of meniscal procedures was three times higher in the Capital Region than in Region Zealand.

Conclusions

Our study identified a large increase in the use of meniscal procedures in the public and private sector in Denmark. The increase was particularly conspicuous in the private sector as its proportion of procedures performed increased from 1% to 32%. Substantial regional differences were present in the incidence and trend over time of meniscal procedures.

Keywords: ORTHOPAEDIC & TRAUMA SURGERY, RHEUMATOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Unique nation-wide registration of all hospital contacts and performed procedures in Denmark.

Reliable estimation of time-related trends in surgical procedures.

Coverage and validity are an issue for all registry studies.

Introduction

Arthroscopy for meniscal tears is the most common orthopaedic procedure with at least 700 000 meniscal resections performed in the USA in 2006.1 A recent study reported a large increase in the number of meniscal procedures from 2000 to 2011 in Denmark.2 This increase was observed almost exclusively in middle-aged and older patients despite uncertainty of the added benefit provided by arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) over non-surgical treatments on patient-reported knee pain and function in these age groups with or without osteoarthritis (OA).3–11

The reason for the large increase in arthroscopic surgery for meniscal tears in Denmark is unclear. Danish media have reported an increase in the number and availability of hospitals and clinics in the private sector since 2005.12 In the USA, ambulatory surgery centres owned by physicians have surgical rates at least twice as high as outpatient surgery in public hospitals.13 14 In addition, higher mortality rates and payments have been observed in for-profit hospitals.15 16 In Denmark, public hospitals are also paid per service provided but the financial incentive for the individual surgeon is likely low as this does not affect individual surgeon salary. Furthermore, large regional differences have been reported in the use of surgical interventions.17

To further elucidate the increased use of arthroscopy for meniscal tears in Denmark, we examined the nation-wide distribution of meniscal procedures performed in the private and public sector in Denmark, as different incentives may be present and the use of these procedures may differ from region to region.

Patients and methods

This was a registry study of annual incidences of meniscal procedures in Denmark. We extracted data from The Danish National Patient Register (DNPR). The DNPR registers all patient contacts with hospitals (public and private) in Denmark.18 Administrative data include the unique person identification number given to all residents in Denmark (Central Person Register—CPR-number19), hospital identification, date and time of activity, patient municipality, etc. Clinical data include types of surgical procedures (Nordic Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP)) and diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)). Data were retrieved on all patients who underwent arthroscopic meniscus surgery (KNGD and all subcodes) either as a primary procedure or as part of other surgery in the years 2000 to 2011 (including both years). The CPR-number was used to track patients with several meniscal surgeries (defined as surgery on separate dates) in the study period. In total, 151 228 procedures were performed on 148 819 individual patients.2 Data were extracted on age and sex together with hospital identification code for each contact, which enables linkage of performed procedures to specific public and private hospitals as well as geographic location. For regional differences, data were obtained from 2005 to 2011. The Regions in Denmark were first established in 2007 in a merger of different municipalities and counties, however, population data are available from 2005.

The DNPR has formed the basis for payment of public healthcare services performed at both public and private hospitals since the year 2000 via the Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG) system in Denmark. It is assumed that registration is complete for these services at public and at private hospitals since 2000. However, for patient paid and private healthcare insurance paid services performed in the private sector, reporting is not complete even though this has been mandatory since 2003. In 2008, it was estimated by the Danish National Board of Health that 5% of all private surgeries were missing in the DNPR.18 Registration of orthopaedic procedures has been reported to be correct in 92% of a sample of cases (inpatients and outpatients) and is even better for outpatients alone.20 Arthroscopy codes from public hospitals were recently validated for cartilage injuries of the knee. Registration was correct in 88% of 117 patients.21

Denmark is divided into five regions: The Capital Region, Region Zealand, Region of Southern Denmark, Region Mid and Region North. Information on numbers of registered inhabitants of all ages in each region, per 1 January, for each year in the period from 2005 to 2012, was retrieved from Danish Statistics (http://www.statistikbanken.dk—accessed 13 March). Mid-year population was estimated from numbers at the beginning and end of each year. Yearly incidence of arthroscopic meniscal procedures per 100 000 inhabitants (all ages) was calculated with 95% CI for procedures performed in the public and private sector, respectively, for each region.

The χ2 test was used to assess differences in proportions of meniscal procedures performed on middle-aged and older patients, defined as aged 35 years and older, in the public sector compared with the private sector.

Ethics

Data were extracted from the DNPR with approval from Statens Serum Institut (study ID: FSEID 00000526), which is the Danish authority responsible for the DNPR. In addition, the study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (study ID: 2013-41-1792), which must approve all extractions of personal data for research purposes from the DNPR. As the present study only pertains to register-based data it can be conducted without permission from the Ethics Committee according to Danish legislation (Committee Act § 1, paragraph 1).

Results

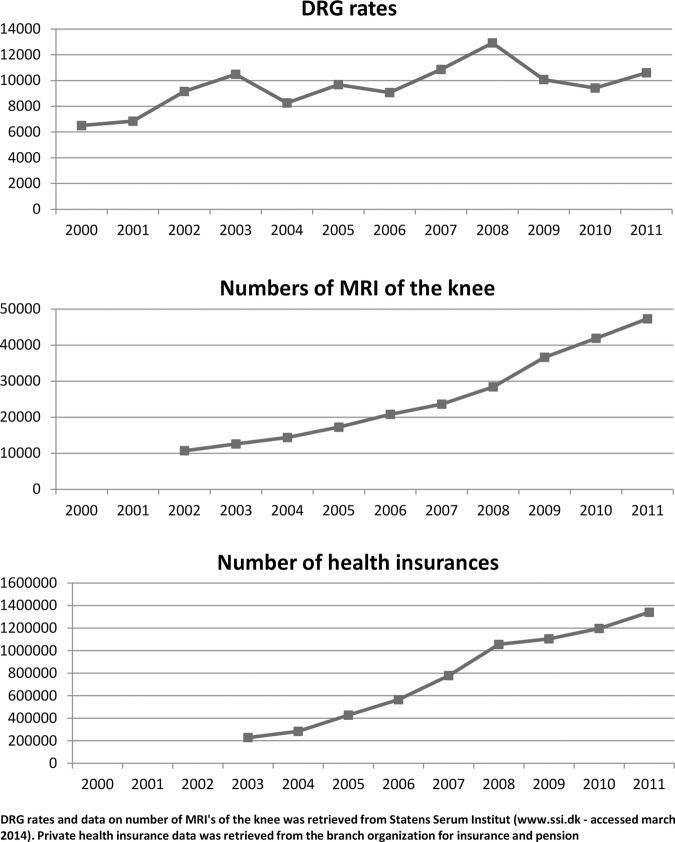

Incidence of meniscal procedures increased at private and at public hospitals. However, the proportion of procedures performed in the private sector increased from 1% in 2000 to 32% in 2011 (figure 1) and the private sector also accounted for the largest increase in total number of procedures, rising from 65 procedures in 2000 to 5478 in 2011. Still, the majority of meniscal procedures in Denmark are carried out in the public sector. In the same time interval, the number of private hospitals and clinics reporting to the DNPR in Denmark more than tripled from 16 in 2000 to 52 in 2011, with the largest increase observed in the Capital Region (from 7 to 24). Yearly incidence of arthroscopic meniscal procedures for the private sector in Denmark increased from 1 (95% CI 0.9 to 1.5) in 2000 to 98 (96 to 101) in 2011. The increase in incidence in the public sector in the same time period rose from 163 (159 to 166) to 213 (210 to 217). There was a significant difference (p<0.001) in age distribution as the private sector performed 83% of the procedures in patients aged 35 years and older compared to 73% in the public sector (table 1).

Figure 1.

Total number of meniscal procedures divided between public and private hospitals/clinics from 2000 to 2011 in Denmark.

Table 1.

Number of meniscal procedures distributed by age and public or private sector

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >55 years | |||||||||||||

| Public | 1478 | 1640 | 2023 | 2104 | 2228 | 2585 | 2630 | 2772 | 2268 | 3236 | 3834 | 3779 | 30 577 |

| Private | 32 | 35 | 98 | 231 | 240 | 261 | 336 | 710 | 1435 | 1446 | 1467 | 1331 | 7622 |

| 35–55 years | |||||||||||||

| Public | 4129 | 4382 | 4853 | 4974 | 5037 | 5241 | 5117 | 4830 | 3688 | 5196 | 5364 | 5275 | 58 086 |

| Private | 26 | 58 | 185 | 434 | 530 | 524 | 675 | 1569 | 2859 | 3297 | 3401 | 3361 | 16 919 |

| <35 years | |||||||||||||

| Public | 3078 | 2994 | 3111 | 2921 | 2867 | 2751 | 2798 | 2508 | 1957 | 2499 | 2783 | 2836 | 33 103 |

| Private | 7 | 26 | 99 | 203 | 169 | 212 | 189 | 463 | 903 | 941 | 923 | 786 | 4921 |

| Total | |||||||||||||

| Public | 8685 | 9016 | 9987 | 9999 | 10 132 | 10 577 | 10 545 | 10 110 | 7913 | 10 931 | 11 981 | 11 890 | 121 766 |

| Private | 65 | 119 | 382 | 868 | 939 | 997 | 1200 | 2742 | 5197 | 5684 | 5791 | 5478 | 29 462 |

Large regional differences were present (table 2). In 2011, the total incidence (public and private) in the Capital Region was three times higher than in Region Zealand. The largest increase in incidence between 2005 and 2011 occurred in the Capital Region, from 165 (159–171) to 366 (357–375), while in two regions, Zealand and North, the incidence remained stable between 2005 and 2011.

Table 2.

Number and incidence rates of meniscus procedures in the different regions in Denmark

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||||||

| Public, n | 10 577 | 10 545 | 10 110 | 7913 | 10 931 | 11 981 | 11 890 |

| Private, n [%] | 997 [9] | 1200 [10] | 2742 [21] | 5197 [40] | 5684 [34] | 5791 [33] | 5478 [32] |

| Public incidence | 195 (191 to 199) | 194 (190 to 198) | 185 (182 to 189) | 144 (141 to 147) | 198 (194 to 202) | 216 (212 to 220) | 213 (210 to 217) |

| Private incidence | 18 (17 to 20) | 22 (21 to 23) | 50 (48 to 52) | 95 (92 to 97) | 103 (100 to 106) | 104 (102 to 107) | 98 (96 to 101) |

| Region capital | |||||||

| Public, n | 2370 | 2357 | 2230 | 1767 | 2565 | 3366 | 3084 |

| Private, n [%] | 325 [12] | 380 [14] | 866 [28] | 1760 [50] | 1948 [43] | 2152 [39 | 3167 [51] |

| Public incidence | 145 (139 to 151) | 144 (138 to 150) | 136 (130 to 142) | 107 (102 to 112) | 153 (148 to 159) | 199 (192 to 206) | 181 (174 to 187) |

| Private incidence | 20 (18 to 22) | 23 (21 to 26) | 53 (49 to 56) | 106 (101 to 111) | 117 (111 to 122) | 127 (122 to 133) | 186 (179 to 192) |

| Region Zealand | |||||||

| Public, n | 1013 | 999 | 879 | 717 | 883 | 913 | 792 |

| Private, n [%] | 46 [4] | 37 [4] | 91 [9] | 176 [20] | 252 [22] | 332 [27] | 221 [22] |

| Public incidence | 125 (118 to 133) | 123 (115 to 130) | 107 (100 to 115) | 87 (81 to 94) | 108 (100 to 115) | 111 (104 to 119) | 97 (90 to 103) |

| Private incidence | 6 (4 to 7) | 5 (3 to 6) | 11 (9 to 13) | 21 (18 to 25) | 31 (27 to 34) | 40 (36 to 45) | 27 (23 to 31) |

| Region South | |||||||

| Public, n | 2576 | 2601 | 2355 | 1769 | 2999 | 3072 | 3429 |

| Private, n [%] | 339 [12] | 443 [15] | 677 [22 | 1204 [40] | 1020 [25] | 965 [24] | 811 [19] |

| Public incidence | 217 (209 to 226) | 219 (211 to 227) | 198 (190 to 205) | 148 (141 to 155) | 250 (241 to 259) | 256 (247 to 265) | 286 (276 to 295) |

| Private incidence | 29 (26 to 32) | 37 (34 to 41) | 57 (53 to 61) | 101 (95 to 106) | 85 (80 to 90) | 80 (75 to 85) | 68 (63 to 72) |

| Region Mid | |||||||

| Public, n | 3389 | 3464 | 3692 | 3066 | 3607 | 3751 | 3449 |

| Private, n [%] | 177 [5] | 207 [6] | 487 [12] | 823 [21] | 1545 [30] | 1486 [28] | 1003 [23] |

| Public incidence | 279 (269 to 288) | 283 (274 to 296) | 300 (290 to 309) | 247 (238 to 256) | 288 (279 to 298) | 298 (289 to 308) | 273 (264 to 282) |

| Private incidence | 15 (12 to 17) | 17 (15 to 19) | 40 (36 to 43) | 66 (62 to 71) | 124 (117 to 130) | 118 (112 to 124) | 79 (74 to 84) |

| Region North | |||||||

| Public, n | 1229 | 1124 | 954 | 594 | 877 | 879 | 1136 |

| Private, n [%] | 110 [8] | 133 [11] | 621 [39] | 1234 [68] | 919 [51] | 856 [49] | 276 [20] |

| Public incidence | 213 (201 to 225) | 195 (183 to 206) | 165 (155 to 176) | 102 (94 to 111) | 151 (141 to 161) | 152 (142 to 162) | 196 (185 to 207) |

| Private incidence | 19 (16 to 23) | 23 (19 to 27) | 107 (99 to 116) | 213 (201 to 225) | 158 (148 to 169) | 148 (138 to 158) | 48 (42 to 53) |

Numbers in brackets are 95% CI.

N, number of procedures.

Incidence of meniscal procedures in the private sector increased in all regions. In Region Mid the overall increase was exclusively caused by an increase in incidence of procedures performed in the private sector while the incidence of procedures increased in the public as well as private sector in the Capital Region and in Region of Southern Denmark. In Region North, the incidence at private hospitals increased while the incidence rate decreased at public hospitals. In 2011 more meniscal procedures were performed in the private sector than in the public sector in the Capital Region while the public sector still accounted for most procedures performed in all other regions.

Discussion

Key results

We examined the distribution of public and private sector meniscal procedures performed in Denmark together with regional differences. Incidence of meniscal procedures rose in the public and in the private sectors but the proportion of procedures performed in the private sector increased from 1% to 32% over the 12-year period. In the same time period, the incidence of meniscal procedures performed in the public sector increased by 31%. The proportion of procedures performed in patients aged 35 years and older was larger in the private sector: 83% compared to 73% in the public sector. While the incidence was stable in two regions (Zealand and North), it increased markedly in the public as well as the private sector in the Capital Region and in the Region of Southern Denmark. In Region Mid the increase in incidence of procedures was observed exclusively in the private sector.

Interpretation

There may be several reasons for the increase in incidence of meniscal procedures performed in the public and private healthcare sectors in Denmark. The most obvious would be an increased incidence of meniscal tears, which could be caused by increased sports and exercise participation in the adult population. In Denmark, the proportion of adults who self-reported participation in sport and exercise increased from 50% to 64% from 1998 to 2011. The predominant activities reported were jogging (31% of adult population), strength training (24%) and hiking (23%),22 none of these is recognised as a high risk activity for meniscal injury.23 Even though increased participation in sports and exercise may not lead to direct injury, it may contribute to symptom onset in patients with latent degenerative knee disease such as degenerative meniscal tears. Thus, increased participation in sport and exercise may have caused an increased incidence on patient demand of care (ie, meniscal surgery) but is unlikely to be responsible for the large increase observed.

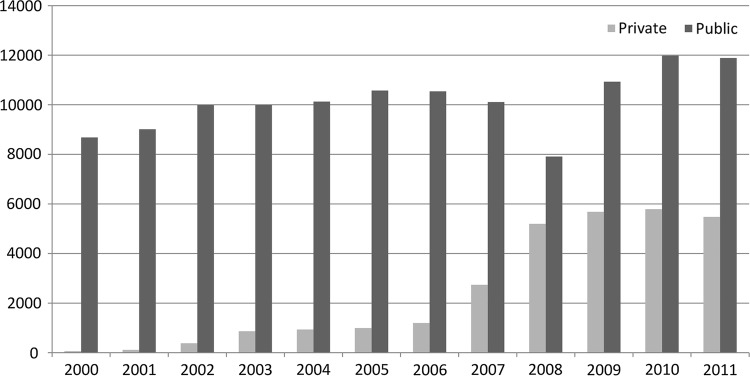

Another plausible reason includes financial reimbursement. In Denmark, the public sector and to some extent the private sector is paid according to the DRG rate. DRG is a classification system for patients originally developed in the USA but modified to fit the Danish diagnosis and treatment definitions.24 DRG rates represent prices for treatments within each group based on estimated average costs. This system was introduced in 1 January 2000. The DRG rate for arthroscopic knee surgery increased from 6502 DKK in 2000 to 10 483 in 2003 and was relatively stable thereafter (figure 2). Payment per procedure provides a potential incentive for surgeons to provide more procedures because payment is dependent on the quantity of care rather than the quality and outcome of care. Indeed, financial reimbursement has been shown to influence surgical decision-making in the private sector because of greater financial incentives for surgeons.13 14 To the best of our knowledge, whether this could also be the case in the public sector, where the financial incentive lies within the department and not the individual surgeon, has not been investigated. Still, a concern remains that surgery in this context may be preferred when watchful waiting and/or physiotherapy is the other, less profitable alternative.18

Figure 2.

Trends of Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG) rate (2000–2011), use of knee MRI examinations (2002–2011) and private health insurances (2003–2011).

Another potential cause is the political introduction of the ‘extended free hospital choice’, also known as the ‘treatment guarantee’, introduced in Denmark on 1 July 2002. The treatment guarantee allows patients to be treated at another public hospital or in the private sector if the initially chosen public hospital is not able to offer treatment within 2 months. This likely led to an increase in incidence of meniscal procedures performed in the private sector as well as in number of private hospitals and clinics in the period 2000 to 2011. The increase in incidence of meniscal procedures was further enhanced when the treatment guarantee was reduced to 1 month on 1 October 2007. In the public sector, there was a decline in incidence of meniscal procedures performed between 2006 and 2008, while in the same time period, a large increase in incidence of procedures was observed in the private sector (figure 1). This could represent patients ‘shifting’ from the public to the private sector as a consequence of the treatment guarantee in combination with a nurses strike in the public sector from April to June 2008.

The proportion of the Danish population having private health insurance increased from 4% in 2003 to 24% in 2011 (figure 2). This likely facilitated access to surgery for those with private health insurance and may have contributed to the shifting of patients from the public to the private sector. Providing quick treatment for patients is often considered beneficial for early recovery and prognosis. However, in conditions where symptoms are known to fluctuate, such as in knee OA, quick access to surgery may actually not be advantageous since symptoms could remit without surgery. Indeed, for middle-aged and older patients, meniscal surgery is most often a resection of a degenerative meniscal tear.2 The knee symptoms of these patients are likely related to degenerative knee disease rather than meniscal tear,25 and it is recommended that the disease be treated according to clinical guidelines of knee OA with patient education, physiotherapy and weight loss if needed.26

MRI examinations of the knee are increasingly used in diagnosing meniscal pathology and could influence surgical decision-making by detecting previously undiagnosed meniscus tears in a painful knee. Meniscal tears visualised on MRI provide a persuasive indication for surgery for the surgeon and for the patient with a painful knee. Indeed, the use of MRI of the knee has increased fivefold between 2002 and 2011 (figure 2). However, positive findings on MRI are common also in asymptomatic individuals and even more common in knees with OA.27 28 The increased use of MRI as a diagnostic tool could lead to treatment of patients whose symptoms are not related to a meniscal lesion, but to knee OA.

Even though financial incentives and the treatment guarantee seem plausible causes for the increased incidence of meniscal procedures, these causes are unlikely to account for the regional variations since regions share the same national reimbursement and healthcare policy. In the present study, we found large differences in incidence of meniscal procedures between regions, with the lowest incidence being 124/100 000 (116–131) in Region Zealand in 2011, compared to a three times greater incidence rate of 366 (357–375) in 2011 in the Capital Region. Large regional variations may suggest variations in surgeons’ opinions about clinical indications for surgery. This is known for indications of knee arthroplasty.29 However, a systematic review showed little evidence of different beliefs in clinical indications as a cause of regional variations in use of coronary angiography, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and carotid endarterectomy.30 If different clinical indications are not the cause of regional variation then high surgical rates in some regions may be related to traditions in surgical training or a strong belief in a specific procedure.31 32 In this study, we found a low incidence of meniscal surgery in Region North but a report on shoulder surgery in Denmark found a high incidence of shoulder arthroscopy in the same region compared to the other regions.33 It seems there is little correlation in regional rates of procedures even within the same specialty. Similar discrepancies have been found in the USA.17

Patient willingness to undergo surgery could be another cause of regional variation and has been reported to be higher in areas with higher incidence for knee arthroplasty.34 There may also be differences in the patient information given and in the willingness to incorporate the patients in the decision-making process of having surgery. These variations are also known to influence surgical rates.35 36

Limitations

There are some limitations associated with our study. The DNPR does not differentiate between the regions patients reside in. It is possible that some patients received surgery in a Region other than their residential region. For instance, Region Zealand is closely related to the Capital Region and some patients may have chosen to be operated in a private hospital in the Capital Region. We assumed that registration in the DNPR has been complete for public hospitals since 2000. However, for private hospitals and clinics, reporting is not complete even though this has been mandatory since 2003. The Danish National Board of Health estimated that 5% of all private surgeries were missing in the DNPR.18 Thus, numbers of procedures in the private sector may be underestimated in the present study and some of the changes observed may be due to variable completeness of reporting.

Conclusions

A large increase in the use of meniscal procedures at public and at private hospitals in Denmark was observed between 2000 and 2011. The increase was particularly conspicuous in the private sector, as the proportion of procedures performed increased from 1% to 32% over the investigated 12-year period. Potential causes for the observed increase include financial reimbursement and healthcare policies along with an increase in number of private health insurances and MRI examinations of the knee. Substantial regional differences were present in the utilisation rate and trend over time of meniscal procedures. The exact reasons for this remain unknown. The increasing use and regional variation of meniscal procedures in the middle-aged and elderly is notable given the uncertainty for added patient-centred benefit from the intervention.

Footnotes

Contributors: LSL and JBT conceived the study. KBH, JHV and JBT were responsible for the collection and analysis of data and all authors contributed to the interpretation of the data. KBH drafted the manuscript, which was critically revised by JHV, JBT and LSL. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by grants from The Danish Council for Independent Research | Medical Sciences (#12-125457).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Danish Data Protection Agency (study ID: 2013-41-1792).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.fq268.

References

- 1.Cullen K, Hall M, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Report 2009;(11):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorlund JB, Hare KB, Lohmander LS. Large increase in arthroscopic meniscus surgery in the middle-aged and older population in Denmark from 2000 to 2011. Acta Orthop 2014;85:287–92. 10.3109/17453674.2014.919558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrlin S, Hållander M, Wange P et al. . Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007;15:393–401. 10.1007/s00167-006-0243-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrlin SV, Wange PO, Lapidus G et al. . Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:358–64. 10.1007/s00167-012-1960-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moseley JB, O'Malley K, Petersen NJ et al. . A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2002;347:81–8. 10.1056/NEJMoa013259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB et al. . A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1097–107. 10.1056/NEJMoa0708333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yim JH, Seon JK, Song EK et al. . A comparative study of meniscectomy and nonoperative treatment for degenerative horizontal tears of the medial meniscus. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:1565–70. 10.1177/0363546513488518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A et al. . Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2515–24. 10.1056/NEJMoa1305189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE et al. . Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1675–84. 10.1056/NEJMoa1301408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gauffin H, Tagesson S, Meunier A et al. . Knee arthroscopic surgery is beneficial to middle-aged patients with meniscal symptoms: a prospective, randomised, single-blinded study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:1808–16. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan M, Evaniew N, Bedi A et al. . Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative tears of the meniscus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2014;186:1057–64. 10.1503/cmaj.140433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Møller KP. Eksplosiv stigning i omstridte operationer. Altinget 2010.

- 13.Hollingsworth JM, Ye Z, Strope SA et al. . Physician-ownership of ambulatory surgery centers linked to higher volume of surgeries. Health Aff 2010;29:683–9. 10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell JM. Effect of physician ownership of specialty hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers on frequency of use of outpatient orthopedic surgery. Arch Surg 2010;145:732–8. 10.1001/archsurg.2010.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devereaux PJ, Heels-Ansdell D, Lacchetti C et al. . Payments for care at private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2004;170:1817–24. 10.1503/cmaj.1040722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devereaux PJ, Choi PT, Lacchetti C et al. . A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing mortality rates of private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals. CMAJ 2002;166:1399–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birkmeyer JD, Reames BN, McCulloch P et al. . Understanding of regional variation in the use of surgery. Lancet 2013;382: 1121–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61215-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):30–3. 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):22–5. 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lass P, Lilholt J, Thomsen L et al. . Kvaliteten af diagnose- og procedurekodning i Ortopædkirurgi Nordjylland. Ugeskr Læger 2006;168:4212–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mor A, Grijota M, Norgaard M et al. . Trends in arthroscopy-documented cartilage injuries of the knee and repair procedures among 15–60-year-old patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laub TB, Pilgaard M. Sports participation in Denmark 2011. Danish Institute for Sports Studies, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snoeker BA, Bakker EW, Kegel CA et al. . Risk factors for meniscal tears: a systematic review including meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2013;43:352–67. 10.2519/jospt.2013.4295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vrangbæk K, Bech M. County level responses to the introduction of DRG rates for “extended choice” hospital patients in Denmark. Health Policy 2004;67:25–37. 10.1016/S0168-8510(03)00085-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Englund M, Roemer FW, Hayashi D et al. . Meniscus pathology, osteoarthritis and the treatment controversy. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012;8:412–19. 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JWJ et al. . EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1125–35. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guermazi A, Niu J, Hayashi D et al. . Prevalence of abnormalities in knees detected by MRI in adults without knee osteoarthritis: population based observational study (Framingham Osteoarthritis Study). BMJ 2012;29:e5339 10.1136/bmj.e5339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Englund M, Guermazi A, Gale D et al. . Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1108–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa0800777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Troelsen A, Schroder H, Husted H. Opinions among Danish knee surgeons about indications to perform total knee replacement showed considerable variation. Dan Med J 2012;59:A4490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keyhani S, Falk R, Bishop T et al. . The relationship between geographic variations and overuse of healthcare services: a systematic review. Med Care 2012;50:257–61. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182422b0f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chassin MR. Explaining geographic variations. The enthusiasm hypothesis. Med Care 1993;31(5 Suppl):37–44. 10.1097/00005650-199305001-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bederman SS, Coyte PC, Kreder HJ et al. . Who's in the driver's seat? The influence of patient and physician enthusiasm on regional variation in degenerative lumbar spinal surgery: a population-based study. Spine 2011;36:481–9. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d25e6f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Løvschall C, Witt F, Svendsen S et al. . Medicinsk teknologivurdering af kirurgisk behandling af patienter med udvalgte og hyppige skulderlidelser. Århus: MTV og Sundhedstjenesteforskning, Region Midtjylland 2011.

- 34.Hawker G, Wright JG, Coyte PC et al. . Determining the need for hip and knee arthroplasty: the role of clinical severity and patients’ preferences. Med Care 2001;39:206–16. 10.1097/00005650-200103000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arterburn D, Wellman R, Westbrook E et al. . Introducing decision aids at Group Health was linked to sharply lower hip and knee surgery rates and costs. Health Aff 2012;31:2094–104. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCulloch P, Nagendran M, Campbell WB et al. . Strategies to reduce variation in the use of surgery. Lancet 2013;382:1130–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61216-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]