Abstract

Considerable controversy surrounds the role of traditional health practitioners (THP) as first contact service providers and their influence on the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in sub-Saharan Africa. This study examined first-contact patterns and pathways to psychiatric care among individuals with severe mental illness in South Africa. A cross-sectional study was conducted at a referral-based tertiary psychiatric government hospital in KwaZulu-Natal Province. Information on pathways to care was collected using the World Health Organization’s Encounter Form. General hospital was the most common first point of contact after mental disorder symptom onset and the strongest link to subsequent psychiatric treatment. Family members were the most common initiators in seeking care. First contact with THP was associated with longer DUP and higher number of provider contacts in the pathway based on adjusted regression analyses. Strengthening connections between psychiatric and general hospitals, and provision of culturally-competent family-based psychoeducation to reduce DUP are warranted.

Keywords: pathway to care, duration of untreated psychosis, traditional health practitioner, severe mental illness, South Africa

Introduction

Traditional beliefs, medicine and health practitioners play an important role in the healing of lives in Africa (Essien, 2013), including the management of psychosis in South Africa (Sorsdahl et al, 2010). Considerable treatment gaps and inadequate human resources for mental health care exist in South Africa, where the traditional health practitioner (THP) may sometimes provide a geographically-accessible and culturally-appropriate first port of call for services for people with mental illnesses (Burns, 2011). The contribution of THPs in a modern healthcare system in South Africa has been a contentious issue (Kale, 1995), with African-based studies reporting contradictory results regarding their contributions and raising questions about their role as first contact service providers. The influence of THPs on the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in South Africa is unknown owing to the paucity of studies. Longer DUP has serious consequences, including disability and poorer response to treatment in low-and-middle income countries settings (Farooq et al, 2009). This study examined the role of THPs in treatment pathways for individuals with severe mental illness (SMI) attending mental health services in South Africa.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted at a referral-based tertiary psychiatric government hospital in the KwaZulu-Natal Province. All consecutive individuals admitted into inpatient services (July 2012–October 2013) who met study criteria were approach to enter the study. The inclusion criteria were isiZulu (or English) speaking individuals 21 years and older diagnosed with SMI, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder and psychosis not otherwise specified. Excluded were individuals with developmental disability or unable to provide informed consent. Participants meeting the criteria were provided with the description of the study, and written informed consent was obtained. The response rate for the pathway to care study among total eligible sample was 92.0%. The Columbia University Institutional Review Board and University of KwaZulu-Natal Biomedical Research Ethics Committee approved the study.

Measures

Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), defined as the number of months from manifestation of the first psychotic symptom to initiation of adequate antipsychotic drug treatment at the psychiatric hospital, and number of different service provider contacts seen during pathway, were the two outcome measures of the study. The primary study exposure was the type of service provider first consulted by study participants. Traditional health practitioner (THP) encompassed traditional and religious healers. Information on primary exposure and outcomes was derived from the World Health Organization’s Encounter Form (World Health Organization, 1987) which is based on self-report and documents from whom (up to three contacts) and when (month and year) help is sought since the onset of psychotic symptoms. The Encounter, as well as a questionnaire collecting data on socio-demographics, diagnosis and past psychiatric hospital admissions, was translated into isiZulu using the WHO-recommended translation/back-translation/expert panel review method.

Data analyses

After demographic/clinical characteristics analysis of study participants, we assessed the types of service providers with whom study participants first came into contact after mental disorder symptom onset. The analysis was repeated to assess types of first contact initiator (e.g. family member). Secondly, we traced treatment routes to tertiary psychiatric care using a pathway diagram. Lastly, we assessed the association between first contacts with THP (compared to formal services provider) and duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), as well as number of different service provider contacts seen during the pathway. Adjusted Poisson regressions were fitted due to positive skewedness of outcome. We adjusted for gender, age, psychiatric disorder, education, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, urban/rural and history of previous psychiatric admission in the regression analyses. All analyses were conducted in STATA 13.

Results

57 participated in the pathway to psychiatric care interview (Table 1). Approximately two-thirds (n=37) were male and the majority were black South African (n=47; 82.5%). More than half (57.9%) had a previous history of admission to the same tertiary psychiatric hospital. Over half (n=30) had hospitalization related to mental health within the past year. Only 13% (n=7) were married, and the commonest age group was 21–29 (42.1%). Approximately half (n=26) were diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of pathway to care study respondents (n=57)

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 37 | 64.9 |

| Female | 20 | 35.1 |

| Age category | ||

| 21–29 | 24 | 42.1 |

| 30–39 | 19 | 33.3 |

| 40+ | 14 | 24.6 |

| Education | ||

| <Grade 12 | 30 | 52.6 |

| >=Grade 12 | 27 | 47.4 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Black | 47 | 82.5 |

| Non-Black | 10 | 17.5 |

| Marital status‡ | ||

| Married/Stable partner | 19 | 33.9 |

| Casual partner | 16 | 28.6 |

| No relationship/partner | 21 | 37.5 |

| Income‡ | ||

| None | 6 | 10.7 |

| <R1000 | 15 | 26.8 |

| R1001–R5000 | 30 | 53.6 |

| >R5001 | 5 | 8.9 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 27 | 47.4 |

| Rural | 30 | 52.6 |

| Past Admission [same psychiatric hospital] | ||

| First admission | 24 | 42.1 |

| Not first admission | 33 | 57.9 |

| Hospitalization related to mental health ≤ 1 year [any hospital] | ||

| Yes | 30 | 52.6 |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | ||

| Schizophrenia | 26 | 45.6 |

| Schizoaffective | 11 | 19.3 |

| Bipolar | 12 | 21.1 |

| Psychosis NOS and other | 8 | 14.0 |

One missing response

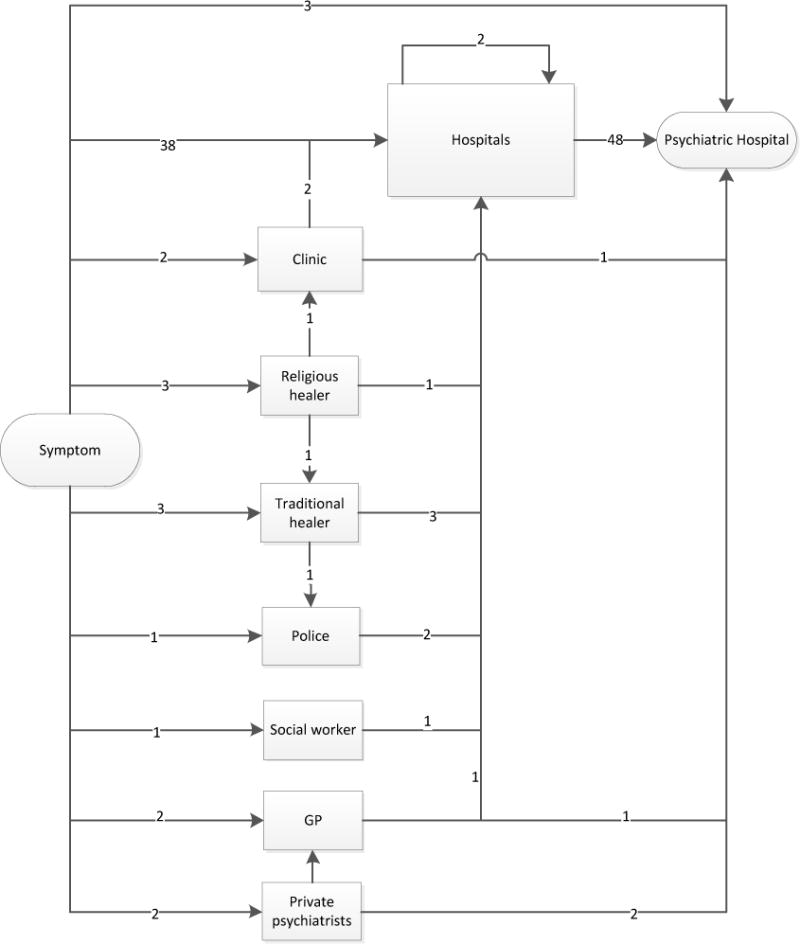

A general hospital (n=37) was the most common first contact since onset of mental disorder symptoms (Table 2); while family members (n=36) were the most common initiators of care (Table 3). The most common link to psychiatric treatment was via general hospitals (Figure 1). The analysis of adjusted regression (Table 4) showed that study participants who had first contact with THP (β = 1.57, z = 4.22, p < 0.01), ages 21–29 (β = 0.85, z = 2.11, p = 0.03), higher educational attainment (β = 0.88, z = 3.04, p < 0.01), married/stable partnership status (β = 0.71, z = 2.09, p < 0.01), and low income (β = 1.26, z = 2.72, p = 0.01) had longer DUP. Furthermore, first contact with THP (β = 1.33, z = 4.52, p< 0.01) and a previous history of psychiatric admission (β = 0.49, z = 2.06, p = 0.04) was associated with a higher number of provider contacts in the pathway to psychiatric treatment.

Table 2.

Frequency of first contact type

| First contact type | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| GP | 2 | 3.9 |

| Private psychiatrist | 2 | 3.9 |

| Social worker | 1 | 1.9 |

| Police | 1 | 1.9 |

| Clinic | 2 | 3.9 |

| Hospital | 38 | 73.1 |

| Traditional/religious healer | 6 | 11.5 |

Table 3.

Frequency of initiator to first seek care

| Initiator type of first contact | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Family/relative | 36 | 73.5 |

| Friend | 2 | 4.1 |

| Patient-initiated | 7 | 14.3 |

| Police | 3 | 6.1 |

| Psychiatrist | 1 | 2.0 |

Figure 1.

Treatment to psychiatric care pathway

Table 4.

Assessing association between first contact and duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and number of contacts outcome using adjusted Poisson regression

| DUP outcome

|

Number of contacts outcome‡

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | Coefficient | SE | Z | p | Coefficient | SE | Z | p |

| First contact [With formal provider] | Traditional and religious healer | 1.57 | 0.37 | 4.22 | <0.01 | 1.33 | 0.29 | 4.52 | <0.01 |

| Gender [Male] | Female | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.63 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 1.26 | 0.21 |

| Age [30–39] | 21–29 | 0.85 | 0.40 | 2.11 | 0.03 | 0.37 | 0.26 | 1.39 | 0.16 |

| 40+ | −0.12 | 0.49 | −0.26 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.95 | |

| Psychiatric disorder [Other] | Schizophrenia | −0.50 | 0.63 | −0.79 | 0.43 | −0.08 | 0.34 | −0.24 | 0.81 |

| Schizoaffective | −0.34 | 0.59 | −0.58 | 0.56 | −0.35 | 0.41 | −0.85 | 0.40 | |

| Bipolar | −0.41 | 0.64 | −0.64 | 0.52 | −0.73 | 0.42 | −1.73 | 0.08 | |

| Education [Lower than grade 12] | Grade 12 and higher | 0.88 | 0.29 | 3.04 | <0.01 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.81 |

| Race/Ethnicity [Non-Black] | Black-South African | −0.73 | 0.44 | −1.64 | 0.10 | −0.38 | 0.45 | −0.84 | 0.40 |

| Marital status [Single] | Married/Stable partner | 0.71 | 0.34 | 2.09 | 0.04 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 1.52 | 0.13 |

| Casual partner | 0.65 | 0.42 | 1.54 | 0.12 | 0.64 | 0.35 | 1.81 | 0.07 | |

| Income [R1001–R5000 per month] | No income | 1.26 | 0.46 | 2.72 | 0.01 | −0.22 | 0.51 | −0.44 | 0.66 |

| <R1000 | −0.03 | 0.45 | −0.07 | 0.95 | −0.34 | 0.28 | −1.24 | 0.22 | |

| >R5001 per month | 0.26 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.66 | −0.57 | 0.60 | −0.96 | 0.34 | |

| Residence [Urban] | Rural | −0.11 | 0.36 | −0.31 | 0.76 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.98 |

| Psychiatric hospital admission [Past] | First admission | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.72 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 2.06 | 0.04 |

Reference category in bracket. The other psychiatric disorder category includes diagnosis such as psychosis NOS.

Number of contacts outcome is under square transformation to fit Poisson regression model.

Discussion

The majority of study participants made first contact with general hospitals after the onset of their mental disorder symptoms. Study participants who made first contact with THP, had significantly longer DUP and more contacts with different types of providers. Family members were identified as the most frequent initiators seeking care on behalf of people with SMI. Over half of participants interviewed for the study had been hospitalized for mental health-related illness within the last year.

The magnitude of psychiatric re-hospitalization challenge calls for a continuity of care strategy that strengthens family support, establishes meaningful collaboration with THP, and strengthens the transition of patients between psychiatric and general hospitals. Mindful of overgeneralizations, which might ignore the uniqueness of mental health services in Africa, we note that our findings on first contact or THP/DUP relationship are consistent with previous South African (Mkize et al, 2004; Temmingh et al, 2008) and African-studies (Abiodun, 1995; Gureje et al, 1995; Gureje et al, 2006; Odinka et al, 2014; Patel et al, 1997). However, caution against causal inference or interpretation of the benefit/risk of specific types of first contact service provider (i.e. general hospitals and THP) on DUP is warranted, as our sample size and cross-sectional design was limited. First contact with formal health services, which includes general hospitals, may suggest a more direct pathway to psychiatric hospital care. This finding, however, should not be interpreted as a recommendation that all people with first-onset psychosis should be referred to psychiatric hospitals in order to reduce DUP. The emphasis needs to be on reducing delays in accessing mental health care for people with first onset psychosis; wherever that care is best provided. In terms of our finding that consultation with formal health services hastened pathway to care, it is likely that study participants with an acute case of psychosis requiring immediate initiation of antipsychotic drug treatment were referred sooner (mostly via general hospitals) to the psychiatric hospital. Patients who were less acutely ill may have experienced greater opportunity to choose their preferred practitioner, including THP – therefore prolonging DUP. Our study could not account for symptom severity of patients with schizophrenia at first contact. The intention of this report is to provide a snapshot of pathway to psychiatric care as a foundation for further investigation for identifying a sustainable model of community-based care which is hoped would reduce DUP and avoid unnecessary psychiatric re-hospitalization.

While psycho-education and the building of partnerships between families and providers is important for all patients with psychosis, we would suggest that this strategy is particularly relevant in relation to persons with multiple psychiatric hospitalizations where a major focus is on reducing readmissions. The study has in addition highlighted the importance of developing collaborations with THP as a means of reducing hospital readmissions. As indicated in our study, participants in a married/stable partnership and with higher educational attainment had longer DUP. Despite good intentions, family support and commitment of greater human resources (often associated with higher levels of education), a lack of knowledge about appropriate treatment, or the means of accessing services within the complex and fragmented systems of community care, may have led to unintended consequences for those with SMI. Therefore, enhancing family capacity for viable and sustainable care requires incorporating culturally-competent (Asmal et al, 2011) psycho-education to reduce psychiatric re-hospitalization in South Africa. Future studies, on sustainable models of care that are alternative to those that rely heavily on medication and services solely within traditional psychiatric settings, should employ qualitative methodologies and assess pathways to various community-based providers (including, but not limited to traditional/religious practitioners, social workers, clinics, schools, and general hospitals). This will provide richer and more comprehensive descriptions of help-seeking patterns and types of services/treatment received by persons with severe mental illness in South Africa.

Conclusion

Overall, our results highlight the need for strengthening health systems to improve mental health care by enhancing the connection between psychiatric hospitals and general hospitals. In addition, mental healthcare coordination that promotes transition from inpatient to outpatient care after hospital discharge may require provision of culturally-competent family-based psycho-education as well as the development of systematic links to other elements of the broader health and social system, including collaboration with traditional health practitioners.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: Data collection of the study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director, Fogarty International Center, Office of AIDS Research, National Cancer Center, National Eye Institute, National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute, National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research, National Institute On Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Health, and NIH Office of Women’s Health and Research through the International Clinical Research Fellows Program at Vanderbilt University (R24 TW007988) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The first author was supported by NIH Research Training Grant (R25TW009337), funded by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute of Mental Health. The second and last authors were supported by a grant from NIMH (R21MH093296). The fourth author was supported by the NIMH Training Grant (T32MH013043). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abiodun OA. Pathways to mental health care in Nigeria. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:823–6. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.8.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmal L, Mall S, Kritzinger J, Chiliza B, Emsley R, Swartz L. Family therapy for schizophrenia: cultural challenges and implementation barriers in the South African context. Afr J Psychiatry. 2011;14:367–71. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v14i5.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JK. The mental health gap in South Africa-a human rights issue. Equal Rights Review. 2011;6:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Essien ED. Notions of healing and transcendence in the trajectory of African traditional religion: Paradigm and strategies. Int Rev Missions. 2013;102:236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq S, Large M, Nielssen O, Waheed W. The relationship between the duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in low-and-middle income countries: A systematic review and meta analysis. Schizophr Res. 2009;109:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O, Acha RA, Odejide OA. Pathways to psychiatric care in Ibadan, Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med. 1995;47:125–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O, Lasebikan V. Use of mental health services in a developing country. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:44–49. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale R. Traditional healers in South Africa: a parallel health care system. BMJ. 1995;310:1182–1185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6988.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mkize LP, Uys LR. Pathways to mental health care in KwaZulu–Natal. Curationis. 2004;27:62–71. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v27i3.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odinka PC, Oche M, Ndukuba AC, Muomah RC, Osika MU, Bakare MO, Agomoh AO, Uwakwe R. The socio-demographic characteristics and patterns of help-seeking among patients with schizophrenia in south-east Nigeria. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25:180–91. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Simunyu E, Gwanzura F. The pathways to primary mental health care in high-density suburbs in Harare, Zimbabwe. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32:97–103. doi: 10.1007/BF00788927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsdahl KR, Flisher AJ, Wilson Z, Stein DJ. Explanatory models of mental disorders and treatment practices among traditional healers in Mpumulanga, South Africa. Afr J Psychiatry. 2010;13:284–90. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v13i4.61878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temmingh HS, Oosthuizen PP. Pathways to care and treatment delays in first and multi episode psychosis. Findings from a developing country. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:727–35. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Pathways of patients with mental disorders. 1987 Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1987/mnh_nat_87.1.pdf Accessed July 28, 2014.