Abstract

We report a strikingly unusual case of traumatic intraperitoneal perforation of an augmented bladder from clean intermittent self-catheterisation (CISC), which presented a unique diagnostic challenge. This case describes a 48-year-old T1 level paraplegic, who had undergone clamshell ileocystoplasty for detrusor overactivity, presenting with abdominal distension, vomiting and diarrhoea. Initial investigations were suggestive of disseminated peritoneal malignancy with ascitic fluid collections, but the ascitic fluid was found to be intraperitoneal urine from a perforation of the urinary bladder. This was associated with an inflammatory response in the surrounding structures causing an appearance of colonic thickening and omental disease. Although the diagnostic process was complex due to this patient’s medical history, the treatment plan initiated was non-operative, with insertion of an indwelling urinary catheter and radiologically guided drainage of pelvic and abdominal collections. Overdistension perforations of augmented urinary bladders have been reported, but few have described perforation from CISC.

Background

Augmentation cystoplasty is used to increase bladder volume and decrease bladder storage pressure in patients with neurogenic bladder dysfunction where conservative measures have failed.

Spontaneous bladder perforation following bladder augmentation surgery is reported to be as high as 13%.1 This has an associated mortality rate as high as 25%.2 There are, however, only limited reports of patients presenting with bladder perforation as a result of intermittent self-catheterisation.

The diagnosis is made more challenging as many of these patients have markedly altered sensation. As such, a high index of suspicion must be exercised in patients presenting with abdominal distension, pain or fever following bladder augmentation to ensure prompt investigation and treatment are initiated.

We report a case of bladder perforation secondary to intermittent self-catheterisation following ileocystoplasty. We discuss the patients presenting symptoms and signs, investigations used in making the diagnosis and potential management plans.

Case presentation

We describe the case of a 48-year-old man who presented to the emergency department while holidaying in Northern Ireland, reporting of a 6-day history of bilateral shoulder tip pain with vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal distension. Medical history included paraplegia secondary to traumatic T1 spinal cord transection, and clam-shell ileocystoplasty which was performed in London in a number of years previously and was well managed with clean intermittent self-catheterisation. Otherwise he was a fit and healthy non-smoker with managed disability independently. Abdominal examination demonstrated a soft but distended abdomen with evidence of ascites, due to his paraplegia no abdominal pain could be elicited, and remaining physical examination was unremarkable. Urinalysis was positive for coliforms, and his inflammatory markers were elevated consistent with infection.

Investigations

CT of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, which diagnosed significant ascites, with associated right-sided colonic mural thickening suspicious of malignant disease with omental depositis; as such a diagnostic paracentesis was performed, this is demonstrated in figures 1 and 2. Surprisingly, cytology did not isolate any malignant cells and subsequent culture confirmed the presence of group B Streptococcus. Ascitic fluid continued to collect and a CT-guided pigtail drain was inserted to good effect; this repeat imaging noted an abnormal appearance to the dome of the bladder suggestive of bladder injury from self-catheterisation. An urgent CT urogram was arranged which noted free flow of contrast into a large right-sided abdominal collection and into the aforementioned pigtail drain; the contrast leak is clearly demonstrated in figure 3. The cause was felt to be a bladder perforation, due to the abnormal shape of the bladder and evidence of soft tissue thickening in the dome. Reanalysis of his ‘ascitic’ fluid confirmed it to be urine.

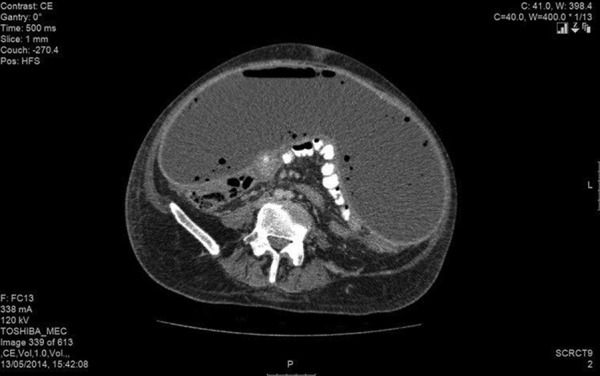

Figure 1.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT demonstrating a large intrabdominal fluid collection, containing gas anteriorly and multiple tiny locules of gas.

Figure 2.

Sagittal reconstruction contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen demonstrating the relationship of the collection to the reconstructed bladder.

Figure 3.

CT urogram, obtained 6 min postintravenous contrast administration showing free leakage of urinary bladder content into the abdominal collection. Note the percutaneous drain on the left side of the abdomen.

Treatment

Intravenous antibiotics were initiated to treat the coliform urinary tract infection and an indwelling urinary catheter (IDC) was inserted. In view of his complex previous bladder augmentation surgery, which was performed in a specialist unit in London, his case was discussed with the local urology team. They recommended a trial of non-operative management with IDC and serial imaging. This treatment plan was initiated and further CT of the abdomen and pelvis confirmed a rapidly decreasing size of the collection with almost complete resolution of symptoms.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient required one further ultrasound scan-guided drainage procedure to drain a remaining loculated pelvic collection. He was discharged from hospital with his urinary catheter in situ after a 3-week inpatient admission and his care was returned to his urology team in London. To date he has not required any subsequent surgical intervention.

Discussion

The challenge of making an accurate diagnosis in patients with spinal cord injury presenting with abdominal symptoms has long since been recognised.3 Intraperitoneal bladder perforation with subsequent abscess or peritonitis can develop before the patient experiences any symptoms. As such, a high index of suspicion must be maintained to ensure early diagnosis. Delay in diagnosis and treatment has been identified as a major factor in mortality from bladder perforation in these patients.4 5

The literature suggests that patients tend to present with anorexia, vomiting, oliguria, abdominal distension, abdominal or referred pain and fever.6 CT of the abdomen and pelvis can demonstrate free abdominal fluid, thickened bladder wall and abscess but may not demonstrate small augmented bladder wall defects. Plain film or CT cystography appears to be a more useful diagnostic modality when bladder perforation is suspected with CT having the advantage of diagnosing other causes of abdominal distension in this patient group.7

Factors that increase the likelihood of spontaneous bladder perforation following augmentation cystoplasty include choice of bowel segment, chronic infection, catheterisation injury and high bladder pressures.8 Although the numbers in these studies are small, it would appear that there is increased incidence of perforation in ileocystoplasty compared to gastrocystoplasty (p<0.05). The cause of high bladder pressures is as a result of detrusor overactivity, poor compliance with catheterisation and bladder outlet resistance. It is thought that increased bladder wall tension leads to ischaemic necrosis in the bowel segment.9

Although conservative management of intraperitoneal bladder perforation has been described but may not be suitable in all patients.10 11 Conservative management involved treatment with intravenous antibiotics, insertion of an IDC to drain the augmented bladder and percutaneous drainage of intra-abdominal collections. Surgical intervention remains the mainstay of treatment for bladder perforation. This involves laparotomy with primary repair of the augmented bladder defect with long-term continuous bladder drainage to avoid high intravesical pressures.12 There is a recent case report suggesting that laparoscopic bladder repair is feasible and safe in these cases also.13

Bladder perforation following augmentation cystoplasty presents a challenge particularly in terms of diagnosis. Early diagnosis and treatment improve patient outcomes. While most patients will require surgical repair of the bladder perforation there may be a subgroup of patients who can be managed conservatively. Laparoscopic surgery is likely to play a more prominent role in the management of this problem in the future. In this case, the patient made a full recovery within 1 month; this is felt to be a particularly positive outcome when compared to the potential recovery time that would be required for a paraplegic patient undergoing either open or laparoscopic bladder repair.

Learning points.

This unusual case demonstrates the difficulty in successfully diagnosing patients with spinal cord injury and the importance of thorough investigation.

Despite performing clean intermittent self-catheterisation successfully multiple times per day, this case highlights how, in the case of paraplegic patients, injury can go easily undetected.

This case was managed non-operatively and demonstrates that a successful outcome can be achieved without surgery in some instances.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Shekarriz B, Upadhyay J, Demirbilek S et al. Surgical complications of bladder augmentation: comparison between various enterocystoplasties in 133 patients. Urology 2000;55:123–8. 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00443-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elder JS, Snyder HM, Hulbert WC et al. Perforation of the augmented bladder in patients undergoing clean intermittent catheterization. J Urol 1988;140:1159–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoen TI, Cooper IS. Acute abdominal emergencies in paraplegics. Am J Surg 1948;75:19–24. 10.1016/0002-9610(48)90281-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couillard DR, Vapnek JM, Rentzepis MJ et al. Fatal perforation of augmentation cystoplasty in an adult. Urology 1993;42:585–8. 10.1016/0090-4295(93)90283-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson PA, Rickwood AM. Detrusor hyper-reflexia is a factor in spontaneous perforation of augmentation cystoplasty for neurogenic bladder. Br J Urol 1991;67:210–12. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1991.tb15112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers CJ, Barber DB, Wade WH. Spontaneous bladder perforation in paraplegia as a late complication of augmentation enterocystoplasty: case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996;77:1198–200. 10.1016/S0003-9993(96)90148-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JH, You HW, Lee CH. Spontaneous intraperitoneal bladder perforation associated with urothelial carcinoma with divergent histologic differentiation, diagnosed by CT cystography. Korean J Urol 2010;51:287–90. 10.4111/kju.2010.51.4.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeFoor W, Tackett L, Minewich E et al. Risk factors for spontaneous bladder perforation after augmentation cystoplasty. Urology 2003;62:737–41. 10.1016/S0090-4295(03)00678-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crane JM, Scherz HS, Billman GF. Ischemic necrosis: a hypothesis to explain the pathogenesis of spontaneously ruptured enterocystoplasty. J Urol 1991;146:141–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slaton JW, Kropp KA. Conservative management of suspected bladder rupture after augmentation enterocystoplasty. J Urol 1994;152:713–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osmann Y, El-Tabey N, Mohsen T et al. Non-operative treatment of isolated posttraumatic intraperitoneal bladder rupture in children—is it justified? Pediatr Urol 2005;173:955–7. 10.1097/01.ju.0000152220.31603.dc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metcalfe PD, Cain MP, Kaefer MA et al. What is the need for additional bladder surgery after bladder augmentation in childhood? J Urol 2006;176:1801–5. 10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang JIC, Gilbourd D, Louie-Johnsun M. Laparoscopic repair of spontaneous perforation of augmentation ileocystoplasty. Urology 2013;81:e15–16. 10.1016/j.urology.2012.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]