Abstract

Muscle rupture is rarely treated surgically. Few reports of good outcomes after muscular suture have been published. Usually, muscular lesions or partial ruptures heal with few side effects or result in total recovery. We report a case of an athlete who was treated surgically to repair a total muscular rupture in the pectoralis major muscle. After 6 months, the athlete returned to competitive practice. After a 2-year follow-up, the athlete still competes in skateboard championships.

Background

In athletes, total rupture of the pectoralis major muscle (PMM) requires surgical treatment, otherwise these athletes may have limited range of motion, cosmetic deformity and functional deficit. In such cases, surgical treatment can be performed selectively.1–5 We describe the surgical treatment of bulk muscular rupture of the PMM.

Case presentation

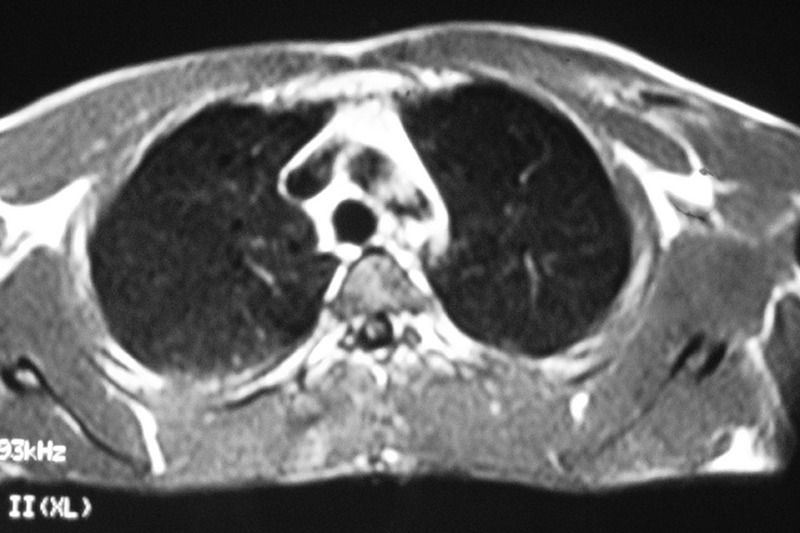

A 32-year-old competitive skateboarding athlete (MVN) suffered a chest wall contusion while freestyle training after the board of another athlete crashed into his chest. The athlete stopped training; the axillary fold was damaged. The athlete felt pain and presented with local oedema. MRI showed a muscular bulk lesion of the pectoralis major (figure 1). An isokinetic test using a dynamometer (Cybex, Model 6000, a Division of Lumex Inc, Ronkonkoma, New York, USA) revealed 26% horizontal adduction deficit at 60°/s. The athlete was treated surgically to repair the muscular lesion. We used an axillar approach to identify the medial and lateral stump of the PMM. The surgical technique employed anchorage knots (figure 2 A, B) using Fiberwire (Arthrex, Naples, Florida, USA) n°2 (figure 2C–E). After surgery, the patient used a sling for 4 weeks and started physiotherapy to get passive range motion and active range motion after 6 weeks. Strength returned after 8 weeks and within 6 months the patient's horizontal adduction deficit was −10%, and the athlete returned to competitive practice. After a 2-year follow-up, the athlete still competes in skateboard championships.

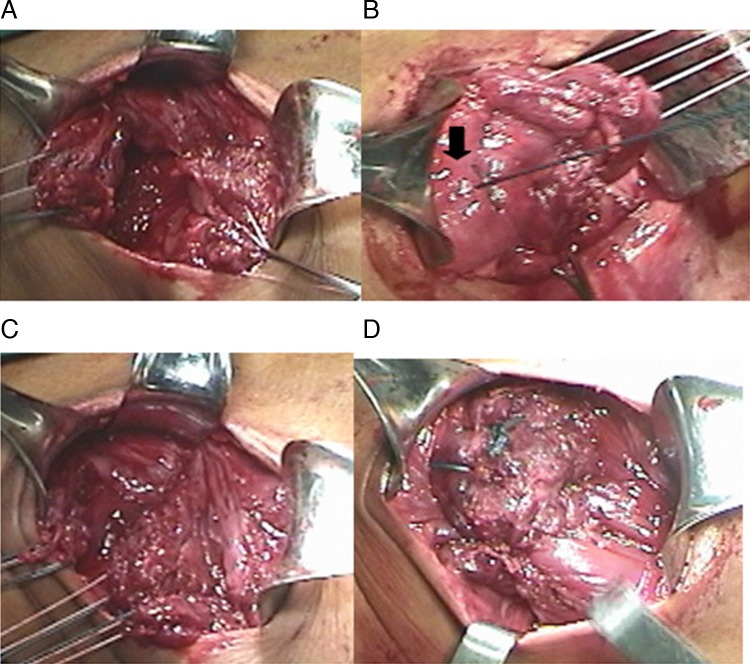

Figure 1.

MRI of a muscle lesion.

Figure 2.

A skating athlete who suffered a pectoralis major muscle (PMM) rupture on the left side: (A) photograph of the total rupture of the muscular portion already isolated proximally to the left and distally to the right, (B) photograph of the PMM proximal portion with non-absorbable suture and anchorage of the suture stitch (for the previous suture) at the central part of the muscle (arrow), (C) photograph showing the distal portion of the isolated PMM and (D) photograph of the final result after suturing the proximal and distal portions of the PMM.

Investigations

MRI showed a muscular bulk lesion of the pectoralis major muscle. An isokinetic test using a dynamometer (Cybex, Model 6000, a Division of Lumex Inc, Ronkonkoma, New York, USA) revealed 26% horizontal adduction deficit at 60°/s. The athlete was treated surgically to repair the muscular lesion using Fiberwire (Arthrex) n°2. After 6 months, horizontal adduction deficit was −10%, and the athlete returned to competitive practice. After a 2-year follow-up, the athlete still competes in skateboard championships.

Differential diagnosis

Poland syndrome (PMM agenesia).

Treatment

The athlete was treated surgically with repair of the muscular lesion end to end using Fiberwire (Arthrex) n°2 (figure 2).

Outcome and follow-up

After 6 months, horizontal adduction deficit was −10%, and the athlete returned to competitive practice.

Now after 2 years follow-up, the athlete is still in skateboard championships.

Discussion

It is uncommon to treat muscle lesions surgically. Few authors have described good results using surgery to treat rupture of the anterior thigh or other muscles.2 5 6

In addition, indirect injuries are most common in athletes with rupture of the PMM. The greatest incidence of PMM rupture occurs in weightlifting athletes (related to anabolic steroid use and to bench press exercises).3 7–9 Deinsertion is usually observed. Muscular rupture of the PMM is uncommon. The direct injury mechanism is related to contact sports, such as rugby and football.10 11

Acute rupture, as described by Schepsis et al,4 may lead to oedema, ecchymosis and haematoma in the anterior region of the thorax, and proximal region of the arm, which generally makes clinical recognition of the affected areas difficult during the acute phase. We agree with Schepsis that ‘acute’ should be defined as a duration within 3 weeks because after this time point, weightlifting athletes usually exhibit tendon dehiscence at the humerus, which is characterised by degeneration and fibrous healing. Routine examinations using ultrasound or MRI of the shoulder may not be successful in identifying PMM ruptures.

The failure of healthcare professionals to swiftly recognise the lesion and insufficient surgical correction guidance given to these athletes have led, in most of these cases, to chronic lesions1 3 4 and visible retraction of the ruptured PMM. Although some authors have reported better functional results from surgery during the acute and chronic stages, we believe that PMM ruptures should be treated similarly to ruptures of the Achilles tendon or the distal biceps brachii. Therefore, if patients are treated sooner, they have a better chance of returning to the same level of physical performance as before the rupture.3

In this case, the patient was not a powerlifting athlete and did not use anabolic steroids.

Clinically, the athlete may present with pain, ecchymosis and oedema at the anterior region of the shoulder and thorax, with functional restraining of adduction and medial rotation, as did our athlete.

Total muscular rupture in the bulk is rare. The literature suggests the following classification, which was described by Tietjen et al:12 (1) contusion, (2) partial injury and (3) total injury. The following subtypes are also suggested: muscular, muscular portion, musculotendinous and tendinous.

The findings in the patient's history and physical tests confirm the diagnosis. Pain, ecchymosis and palpable defect on the anterior axillary region are common findings.11 The patient may also complain of a volume increase in the chest region and report pain and weakness to forced adduction.7

MR allows a better characterisation of the injured structure.11 13 Lee et al11 used MR assessment to demonstrate some essential concepts of the PMM rupture.

Partial lesions at the muscular portion (medial) are usually treated conservatively3 4 using analgaesics, along with rest and immobilisation with slings for 3 weeks and active movement after 10 days.

Some authors have described surgical treatment of muscle lesions with good outcomes, even for chronic injuries.5 6

Straw et al presented one case of a soccer player with a muscle rupture at the rectus femoris, with pain and limited function. After 12 months, the authors performed surgery, and the athlete returned to soccer pain-free after 6 months.

Taylor5 also described a case of a soccer player with rectus femoris rupture and surgical procedure after 10 months of the lesion. He underwent surgical treatment with good outcome.

Although we disagree that the isokinetic evaluation criterion is crucial in determining whether surgery is appropriate, we believe that it represents an important functional improvement evaluation factor regarding adduction strength. Other authors, such as Pochini et al,3 Kretzler,14 Wolfe et al,15 Miller et al,16 Schepsis et al4 and Aarimaa et al,1 have also used isokinetic dynamometry to assess patients.

Ho et al17 presented a muscular lesion in PMM rupture in an elderly patient receiving maintenance haemodialysis. Old age and long-term dialysis could both be risk factors of rupture. Clinicians should pay more attention to this complication when taking care of elderly patients on haemodialysis.

The surgical treatment of selected muscle lesions can have good outcomes.

Learning points.

The surgical treatment in belly muscle rupture can be performed in selected cases.

This pectoralis major muscle rupture presented is a very uncommon lesion, usually we have a desinsertion from the humeral bone.

The direct trauma (this case) can lead a total PMM rupture. The indirect mechanism (weightlifiting athletes) in bench press device is the most common.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Marilia do Santos Andrade for the isokinetic test, Gustavo Cara Monteiro for clinical support and Moises Cohen for research support.

Footnotes

Contributors: ADCP and CVA took part in acquisition of data. BE and NM participated in revision of the article and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Aarimaa V, Rantanen J, Heikkila J et al. . Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:1256–62. 10.1177/0363546503261137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowman KF Jr, Cohen SB, Bradley JP. Operative management of partial-thickness tears of the proximal hamstring muscles in athletes. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:1363–71. 10.1177/0363546513482717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pochini AC, Ejnisman B, Andreoli CV et al. . Pectoralis major muscle rupture in athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:92–8. 10.1177/0363546509347995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schepsis AA, Grafe MW, Jones HP et al. . Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Outcome after repair of acute and chronic injuries. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor C, Yarlagadda R, Keenan J. Repair of rectus femoris rupture with LARS ligament. BMJ Case Rep 2012;2012:pii: bcr0620114359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straw R, Couclough K, Geutjens G. Surgical repair of a chronic rupture of the rectus junction in a soccer player femoris muscle at the proximal musculotendinous. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:182–4. 10.1136/bjsm.37.2.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pochini A, Ejnisman B, Andreoli CV et al. . Reconstruction of the pectoralis major tendon using autologous grafting and cortical button attachment: description of the technique. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012;13:77–80. 10.1097/BTE.0b013e31824478a8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pochini AC, Ejnisman B, Andreoli CV et al. . Exact moment of tendon of pectoralis major muscle rupture captured on video. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:618–19. 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pochini AC, Ejnisman B, Andreoli CV. Clinical considerations for the surgical treatment of pectoralis major muscle ruptures based on 60 cases a prospective study and literature review. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkendall D, Garrett WE Jr. Clinical perspectives regarding eccentric muscle injury. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2002;1:s81–89. 10.1097/00003086-200210001-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J, Brookenthal KR, Ramsey ML et al. . MR imaging assessment of the pectoralis major myotendinous unit: an MR imaging-anatomic correlative study with surgical correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1371–5. 10.2214/ajr.174.5.1741371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tietjen R. Closed injuries of the pectoralis major muscle. J Trauma 1980;20:262–4. 10.1097/00005373-198003000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McEntire JE, Hess WE, Coleman SS. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. A report of eleven injuries and review of fifty-six. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1972;54:1040–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kretzler HH Jr, Richardson AB. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med 1989;17:453–8. 10.1177/036354658901700401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfe SW, Wickiewicz TL, Cavanaugh JT. Ruptures of the pectoralis major muscle. An anatomic and clinical analysis. Am J Sports Med 1992;20:587–93. 10.1177/036354659202000517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller MD, Johnson DL, Fu FH et al. . Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle in a collegiate football player. Use of magnetic resonance imaging in early diagnosis. Am J Sports Med 1993;21:475–7. 10.1177/036354659302100325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho LC, Chiang CK, Huang JW. Rupture of pectoralis major muscle in an elderly patient receiving long-term hemodialysis: case report and literature review. Clin Nephrol 2009;71:451–3. 10.5414/CNP71451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]