Abstract

Rationale, aims and objectives

Given the increasing emphasis being placed on managing patients with chronic diseases within primary care, there is a need to better understand which primary care organizational attributes affect the quality of care that patients with chronic diseases receive. This study aimed to identify, summarize and compare data collection tools that describe and measure organizational attributes used within the primary care setting worldwide.

Methods

Systematic search and review methodology consisting of a comprehensive and exhaustive search that is based on a broad question to identify the best available evidence was employed.

Results

A total of 30 organizational attribute data collection tools that have been used within the primary care setting were identified. The tools varied with respect to overall focus and level of organizational detail captured, theoretical foundations, administration and completion methods, types of questions asked, and the extent to which psychometric property testing had been performed. The tools utilized within the Quality and Costs of Primary Care in Europe study and the Canadian Primary Health Care Practice-Based Surveys were the most recently developed tools. Furthermore, of the 30 tools reviewed, the Canadian Primary Health Care Practice-Based Surveys collected the most information on organizational attributes.

Conclusions

There is a need to collect primary care organizational attribute information at a national level to better understand factors affecting the quality of chronic disease prevention and management across a given country. The data collection tools identified in this review can be used to establish data collection strategies to collect this important information.

Keywords: chronic diseases, data collection tools, disease management, organizational attributes, primary care, systematic search and review

Introduction

Chronic diseases are currently the highest cause of preventable death worldwide, accounting for approximately 36 million deaths annually [1]. Within Canada, 3 out of 5 individuals currently have a chronic disease and the management of chronic diseases accounts for approximately 40–70% of total health care costs [2,3]. As the population ages and the rates of obesity continue to rise, the prevalence and costs associated with chronic diseases will continue to increase. The appropriate management of patients with chronic diseases within the primary care setting can reduce the utilization of health care resources and improve patient outcomes [4]. The delivery of high-quality care to patients with chronic diseases is therefore pivotal to the health and well-being of this patient population, and is an integral component of health care systems worldwide. Given that patients with chronic diseases are primarily managed within the primary care setting 5–8, there is a need to better understand which primary care organizational attributes affect the quality of care that patients with chronic diseases receive.

In general, organizational attributes can be defined as characteristics and structures that are intrinsic to the organization and delivery of care at a practice level. A wide range of innovative organizational attributes, including the addition of allied health care professionals to form multidisciplinary primary care teams, the utilization of electronic medical records (EMRs), changes in physician payment models and extended opening hours, have been implemented within primary care to address the increasing burden that patients with chronic diseases place on the health care system [3,9]. Many of these organizational strategies have purportedly increased access to health care services, enhanced the efficiency of resource utilization and improved chronic disease management 3,9–15. In Canada and many other countries, the implementation of these organizational strategies has occurred at a jurisdictional level, resulting in substantial variability in the chronic disease management delivery models and strategies used in primary care practices across different jurisdictions. Importantly, this variability provides an opportunity to determine which primary care organizational attributes support high-quality care for patients with chronic diseases.

There is currently limited information regarding the distribution and nature of primary care organizational attributes, which has made it difficult to study their effects on chronic disease management. This gap in knowledge may be the result of the variability in tools used to assess a wide range of organizational attributes, the collection of data at jurisdictional levels rather than national levels, and inconsistent and incomplete descriptions of organizational attributes within primary care. The present study aimed to identify, summarize and compare organizational attribute tools associated with chronic disease management that have been used within the primary care setting worldwide.

Methods

Literature search strategy

This study used systematic search and review methodology, as described by Grant and Booth [16]. Systematic search and review methodology consists of a comprehensive and exhaustive search that is based on a broad question to identify the best available evidence. Unlike systematic reviews, the topic area in a systematic search and review is not sharply focused, and considers a wide range of study designs for inclusion, and does not require included articles to undergo critical appraisal [16]. This type of review was necessary to ensure that all existing primary care organizational attribute data collection tools were captured, regardless of their quality or the quality of the study in which they were used within. In addition, prior to study commencement, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [17] and the Joanna Briggs Institute Library of Systematic Reviews [18] were searched and no previous systematic reviews on this topic were identified.

The search strategy aimed to find both published and unpublished studies. An initial search of MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL was undertaken to identify optimal search terms by examining words contained in the title and abstract, and indexing words of relevant articles. Initial search terms were ‘data collection’, ‘chronic disease’, ‘disease management’, ‘delivery of health care’, ‘chronic disease management’ and ‘organizational attribute’. A second extensive search was conducted applying all of the identified search terms and syntax as required by each database. A complete outline of the search terms and syntax used within each database can be found in Supporting Information Table S1. The databases searched included MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, HealthStar, Global Health, PsycINFO, Health and Psychosocial Instruments, and Google Scholar. In addition, reference lists of all relevant articles were searched, and full texts of studies deemed relevant were retrieved to determine eligibility to be included in the review. Key author and journal searches were also conducted, and relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. Subsequently, grey literature databases, including Grey Matters, Mednar and ProQuest, and health care-related web sites on the worldwide web, including the Association of Ontario Health Centers, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, Canadian Institute for Health Information, Canadian Nurses Association, the Commonwealth Fund, the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research and the World Health Organization (WHO), were searched for relevant articles, documents or reports. Additional database searches were conducted once an exhaustive list of organizational attribute data collection tools was developed to ensure that all published articles that used the identified organizational attribute tools were captured. The search terms included in this phase of the study included a combination of the name of the tool, abbreviations used for the tool and alternate names that have been given to the tool (e.g. modified versions). Many organizational attribute tools were not readily available in the published studies and, as a result, the corresponding authors were contacted to request a copy of the tool. This also provided an opportunity to verify with the authors that all relevant articles that used the tool were captured in our search, and in some instances, the corresponding authors provided citations to additional articles that used the tool that had not been previously identified.

Study inclusion criteria

Articles were considered for inclusion if they were specific to the primary care setting and if they identified the name of an organizational attribute tool, even if it was not discussed in detail, if they discussed any aspect of the development of an organizational attribute tool or if they discussed any psychometric properties associated with an organizational attribute tool. Only tools that were intended to be completed by clinic administrative personnel or health care providers were included.

This systematic search and review considered studies that identified tools that collected information on organizational attributes, including those identified within the chronic care model (CCM) [7] and the conceptual framework for primary care organizations [19]. Within the CCM, certain primary care practice organizational attributes are required to ensure appropriate prevention and management of chronic diseases within the primary care setting. These key primary care organizational attributes include self-management support, delivery system design, decision support and clinical information systems [7]. With respect to the conceptual framework for primary care organizations, only studies that identified tools that specifically focused on the ‘organization of the practice’ components from the structural domain were included as they are intrinsic to the primary care practice setting and are important in the delivery of high-quality care for patients with chronic diseases [19].

The primary outcome was to identify and provide an overall description and comparison of primary care organizational attribute tools. Therefore, this systematic search and review considered studies that included any of the following information related to organizational attribute tools: author(s) and/or developer(s), including contact information for corresponding author to acquire a copy of the tool; location of publication; name of the instrument; country of origin; theoretical foundation; setting in which the tool was used; length (e.g. number of items, time it takes to complete the tool); language translations; administration and completion methods; scoring instructions; psychometric properties; clinical applicability (e.g. ease of completion, feasibility of administration, ability to be replicated); description of specific organizational attributes the tool captured; and identification of multidisciplinary elements within the tool.

In accordance with systematic search and review methodology [16], this review considered a range of quantitative study designs including quasi-experimental designs, cohort studies, case control studies, cross-sectional studies, case series, case reports, expert opinions and reports. Qualitative studies were excluded. Only articles written in the English language were included due to lack of resources available to translate information; however, articles were not limited by location of publication. Only articles published prior to April 2013 were included. Unpublished articles were considered for inclusion if a copy of the manuscript was accessible from the authors.

Titles and abstracts were reviewed for relevancy by two independent reviewers, and articles that were deemed relevant were retrieved and assessed for inclusion using pre-established selection criteria. Disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion. The methodological quality of each study was not a focus for the inclusion of the article [16], as the overall aim of this study was to identify and provide an overall description and comparison of primary care organizational attribute tools.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extracted included specific details about the organizational attribute tools. Given the heterogeneity of the studies included with regard to the use of different methodologies, study populations, interventions and outcomes, findings are reported as a narrative summary and include tables and figures to aid in data presentation where appropriate [16].

The organizational attributes measured within each tool were categorized based on a classification system established in a recent scoping review that was conducted on a similar topic [20]. Levesque et al. [20] used a comprehensive process to establish and define organizational concepts used to classify specific attributes captured within tools measuring the attributes and performance of primary health care systems. Specifically, Levesque et al. [20] identified seven organizational concepts including identification of the organization, practice context, organizational vision, organizational resources, organizational structures, service provision and clinical practice, and outputs and outcomes. Within each of these concepts, specific organizational attributes have been defined [20].

Results

Overview

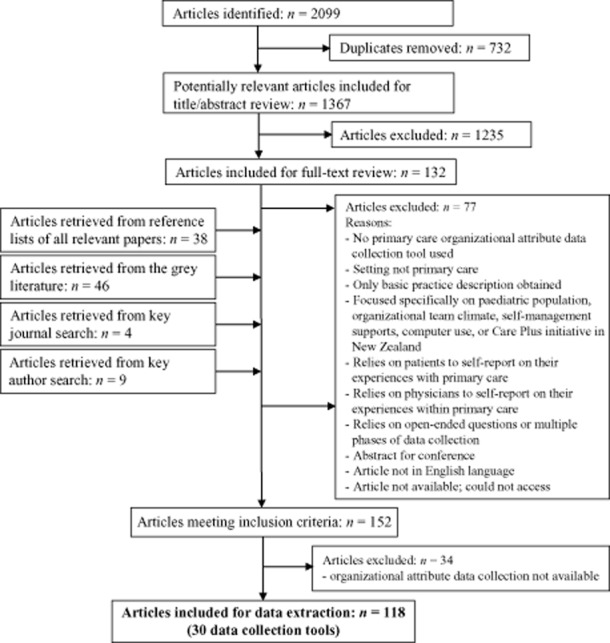

Overall, 152 articles and reports, including three review articles 20–22, met the inclusion criteria for this systematic search and review. Thirty-four articles that were deemed relevant to be included in this systematic search and review had to be excluded because a copy of the organizational attribute data collection tool could not be located in the peer-reviewed literature, and attempts to contact the corresponding author(s) were unsuccessful. A flow diagram providing a detailed breakdown of the search results is located in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of search results.

A total of 30 organizational attribute data collection tools that have been used within the primary care setting worldwide were identified (Table 1). A breakdown of the specific organizational attributes captured within each data collection tool is presented in Table 2. Overall, the most common attributes captured by the data collection tools were technical organizational resources (93%), clinical processes (90%) and quality improvement and patient safety mechanisms (90%) (Table 2). The percentage of attributes captured by each data collection tool is displayed in Fig. 2. The remainder of the results section will serve to emphasize details of the most relevant data collection tools identified from each region. The reader is encouraged to look through Supporting Information Table S2 for a detailed description of each of the tools.

Table 1.

List of organizational attribute data collection tools

| Region | Study or data collection tool | Developer and/or organizational affiliation/sponsor | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| International | Quality and Costs of Primary Care in Europe | Coordinated by the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL) | [30,31] |

| International Survey of Primary Care Doctors | The Commonwealth Fund, Harris Interactive | [23–29] | |

| World Health Organization (WHO) Primary Care Evaluation Tool | Regional Office for Europe of the World Health Organization; the NIVEL | [32–41] | |

| Canada | Primary Health Care Practice-Based Surveys | Canadian Institutes of Health Information | [20,56,57] |

| Primary Care Network Survey | University of Calgary, Alberta | [42] | |

| Organizational Questionnaire | Institut national de santé publique du Québec | [48–53] | |

| Primary Care Organization Surveys | Nova Scotia Department of Health | [55] | |

| Comparison of Models of Primary Health Care in Ontario | University of Ottawa; Elisabeth Bruyère Research Institute | [11–13,44–46] | |

| The Management of Patients with Chronic Illness | University of Alberta | [43] | |

| Accessibility and Continuity of Primary Care in Québec | Principal investigator: Jeannie Haggerty, Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l'université de Montreal | [54] | |

| Survey of Primary Care Practices in Ontario | Collaborative project of the University of Toronto, University of Western Ontario, and McMaster University | [47] | |

| United States of America | Translating Research into Action for Diabetes | Study Coordinating Center: University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey | [82–86] |

| Primary Care Depression Management Organizational Survey | Corresponding author: Dr. Edward P. Post, University of Michigan and Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Centre | [99] | |

| Prescription for Health Independent Evaluation | Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey | [96,97] | |

| Physician Practice and Quality of Care Survey | Corresponding author: Dr. Mark Friedberg, RAND Corporation | [120] | |

| Chronic Disease Prevention and Control Healthcare Practice Surveys | Washington State Department of Health | [98] | |

| National Survey of Physician Organizations and the Management of Chronic Illness | University of California, Berkeley, support of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation | [87–95] | |

| Assessment of Chronic Illness Care | McColl Institute for Healthcare Innovation, Group Health Cooperative | [58–73,79,121–132] | |

| Improving Chronic Illness Care Evaluation Survey | Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; University of California, Berkeley | [66] | |

| 1999 Veterans Health Affairs Survey of Primary Care Practices | Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence for the Study of Healthcare Provider Behaviour | [133–135] | |

| Medical Group Practice Organization Survey | Corresponding author: Dr. Kralewski, Division of Health Services Research and Policy, University of Minnesota | [100,136–138] | |

| Minnesota Health Care Survey for Physicians | Corresponding author: Dr. Nancy Keating, Harvard Medical School | [139] | |

| Primary Care Access Study | Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania, School of Medicine | [101] | |

| Primary Care Assessment Tool | Developed by Dr. Barbara Starfield | [102–107] | |

| Europe | Improving Quality of Care in Diabetes | Institute of Health and Society, Newcastle University; Newcastle Primary Care Trust | [108,140,141] |

| National Survey of the Provision of Diabetes Services | Nuffield Institute for Health, University of Leeds, Leeds, West Yorkshire, England | [109,110] | |

| WHO Primary Care Quality Management Tool | Regional Office for Europe of the World Health Organization; the NIVEL | [74,111] | |

| Survey of the Provision of Diabetes Services in Galway City and County | Corresponding author: Dr. Evans, Department of Public Health, Merlin Park Hospital, Galway, Republic of Ireland | [75,76] | |

| National Survey of Chronic Disease Management in General Practice | Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Trinity College Dublin | [77,78] | |

| Australia | General Practice Chronic Care Team Profile | Centre of Primary Health Care and Equity, University of New South Wales | [80,81,112,113] |

Table 2.

Organizational attributes covered in data collection tools

| Identification of the organization |

Practice context |

Organizational resources |

Organizational structures |

Service provision and clinical practice |

Outputs |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Survey respondent | Location | History and evolution of the clinic | Demographic characteristics | Environment and practice integration | Organizational vision | GPs | Nurses | Other | Economic | Technical | Governance and administration | Funding mechanisms | Clinical processes | QI and patient safety mechanisms | Scheduling and opening hours | Type and range of services | Specific disease management | Degree of integration | Accessibility | Functioning and climate | |

| Percentage of tools measuring attribute (%) | 77 | 53 | 37 | 33 | 63 | 27 | 77 | 77 | 70 | 20 | 93 | 77 | 53 | 90 | 90 | 43 | 53 | 70 | 67 | 60 | 20 |

| QUALICOPC | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| International Survey of Primary Care Doctors | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| WHO Primary Care Evaluation Tool | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Primary Health Care Practice-Based Surveys | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Primary Care Network Survey | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Organizational Questionnaire | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Primary Care Organization Surveys | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| COMP-PC | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| The Management of Patients with Chronic Illness | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Accessibility and Continuity of Primary Care in Quebec | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| Survey of Primary Care Practices in Ontario | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Translating Research into Action for Diabetes | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Primary Care Depression Management Organizational Survey | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Prescription for Health Independent Evaluation | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Physician Practice and Quality of Care Survey | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| Chronic Disease Prevention and Control Healthcare Practice Surveys | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| NSPO and the Management of Chronic Illness | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Assessing Chronic Illness Care | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| ICICE Survey | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| 1999 VHA Survey of Primary Care Practices | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Medical Group Practice Organization Survey | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Minnesota Health Care Survey for Physicians | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| Primary Care Access Study | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| Primary Care Assessment Tool | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Improving Quality of Care in Diabetes | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| National Survey of the Provision of Diabetes Services | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| WHO Primary Care Quality Management Tool | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Survey of the Provision of Diabetes Services in Galway City and County | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| National Survey of Chronic Disease Management in General Practice | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| General Practice Chronic Care Team Profile | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

COMP-PC, Comparison of Models of Primary Health Care in Ontario; GP, general practitioner; ICICE, Improving Chronic Illness Care Evaluation; NSPO, National Survey of Physician Organizations and the Management of Chronic Illness; QI, quality improvement; QUALICOPC, Quality and Costs of Primary Care in Europe; VHA, Veterans Health Affairs.

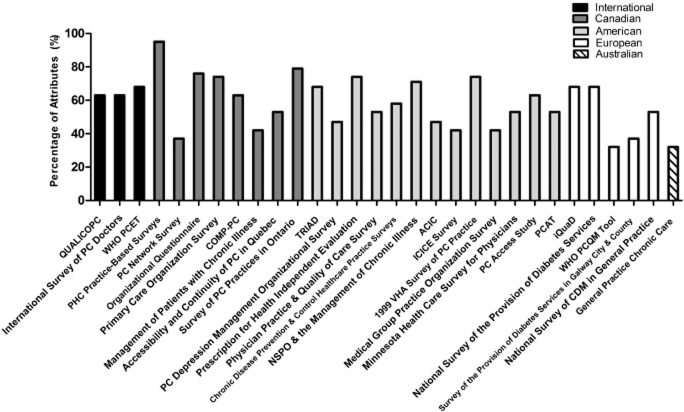

Figure 2.

Percentage of organizational attributes captured within each data collection tool. Each percentage was calculated based on the 19 organizational concepts identified in Table 2. The Canadian Primary Health Care Practice-Based Surveys covered the most organizational attributes.

International

Three international primary care organizational attribute tools, including the International Survey of Primary Care Doctors 23–29, the Quality and Costs of Primary Care in Europe (QUALICOPC) study [30,31] and the WHO Primary Care Evaluation Tool (PCET) 32–41 were identified (Table 1).

The International Survey of Primary Care Doctors was developed by the Commonwealth Fund in the United States and was first used in 2006 to describe primary care organizational attributes that affect the practice's capacity to manage patient care and support quality improvement initiatives. It has also been used to address physicians' views and experiences towards patient access, health information technology capacity, communication across health care sites, feedback related to practice performance, their satisfaction practicing medicine and the overall health care system. The International Survey of Primary Care Doctors was updated in 2009 and 2012, and the most recent version of this survey was administered to primary care physicians in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, Sweden, United Kingdom and the United States to collect information on primary care organizational attributes within these countries [25]. The International Survey of Primary Care Doctors provided respondents with several completion options, including mail, online and telephone or in-person interviews with general practitioners (GPs).

The QUALICOPC study was performed by the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research to describe, compare and analyse how primary health care systems perform in terms of quality, costs and equity across 35 countries, including Australia, Canada, Iceland, Macedonia, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey and 27 countries of the European Union. Four questionnaires were developed as part of the QUALICOPC tool, namely, a practice questionnaire, a GP questionnaire, a patient experiences questionnaire and a patient values questionnaire. The questionnaires were developed through an iterative and comprehensive process involving a literature search, consensus process and pilot survey, and are based on existing validated questionnaires including Starfield's Primary Care Assessment Tool and surveys developed by the Commonwealth Fund. The QUALICOPC questionnaires were paper based and were developed and administered between 2010 and 2013 [30,31]. No studies reporting the findings from these questionnaires were identified in the present systematic search and review.

The development of the WHO PCET was based on the Primary Care Evaluation Framework and a comprehensive literature review. The WHO PCET has been administered in several countries worldwide including Belarus, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Turkey and Ukraine. It consists of three instruments to evaluate the complexity of the primary care system: a questionnaire to be administered at a national level concerning the situation of primary care policies, a questionnaire for family doctors and a questionnaire for patients. The questionnaire for family doctors is the component of the WHO PCET tool that inquires about organizational attributes that are intrinsic to the practice setting. In 2007 and 2008, the WHO PCET was pilot tested in Turkey and Moscow Oblast. Based on results from the pilot test, modifications to the questionnaire for family doctors were made to make it more factual and clear, its length was reduced by removing questions that were considered to be outside of the scope of family doctors and the terminology utilized throughout the questionnaire was changed to make it more consistent. The content within the questionnaires has been validated by international experts in primary care.

Common gaps in organizational attribute data collected across all three of the international tools related to practice location, history and evolution of the clinic, organizational vision, and economic resources (Table 2).

Canada

Within Canada, eight primary care organizational attribute data collection tools were identified (Table 1). Seven of these tools collected primary care organizational attribute information at a jurisdictional level within the provinces of Alberta [42,43], Ontario 11–13,44–47, Québec 48–54 and Nova Scotia [55].

The Primary Health Care Practice-Based Surveys were the only Canadian tool that was intended to measure primary care characteristics nationally to enable a comprehensive assessment of outcomes, and support the identification of contributing factors. The Primary Health Care Practice-Based Surveys were developed in 2013 based on the framework for primary care organizations, the results-based logic model for primary health care, a scoping review, existing survey tools and feedback from relevant stakeholder groups across Canada [20,56,57]. This tool is available in English and French, and is composed of an organizational-level survey, a provider-level survey and a patient-level survey that can be used separately or together. The organizational-level survey contains questions that provide information on basic practice characteristics, organizational vision, organizational resources, economic resources, technical resources, organizational structures, service provision and clinical practices, and organizational context. It is intended to be completed by an individual who is most familiar with how the primary care practice is organized and operates. The provider-level survey contains questions that provide information on provider demographics, structure and organization of the practice, team functioning, and health care service delivery, and is intended to be completed by all health care providers at the clinic who care for patients. No studies that used the Primary Health Care Practice-Based Surveys were identified in the present systematic search and review, and the psychometric properties of these surveys have yet to be assessed in detail. The Primary Health Care Practice-Based Surveys was the only tool identified in this systematic search and review that collected information on nearly all of the organizational concepts identified in Levesque et al.'s [20] classification system (Fig. 2; Table 2). ‘Demographic characteristics’ of the population or patients served by the practice was the only organizational attribute not captured by this tool (Table 2).

United States

Thirteen primary care organizational attribute data collection tools that originated from the United States were identified (Table 1). The organizational attribute data collection tool that was cited the most in publications (n = 30) of this systematic search and review was the Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (ACIC) survey developed by the MacColl Institute for Healthcare Innovation, Group Health Cooperative 58–73,79,121–132. The ACIC tool was developed in 2000 to help primary care organizations evaluate strengths and weaknesses of their delivery of care for individuals with chronic diseases. The ACIC tool, which is based on the CCM, includes questions that address six elements of the CCM that purportedly relate to the quality of chronic disease prevention and management care, namely, community linkages, self-management support, decision support, delivery system design, clinical information systems and organization of care. The ACIC has very clear completion and scoring instructions and consists of Likert-type scales that range from 0, meaning that the practice has limited support for chronic disease management, to 11, meaning that the practice has fully developed chronic disease management care practices. Previous studies have suggested that the ACIC tool is responsive to changes that result from health care quality improvement efforts and may be a useful tool to guide and monitor quality improvement efforts over time. Specifically, the ACIC tool has been associated with clinical outcomes related to diabetes and cardiovascular care [59,60,62,67,69,70,73,121,122,125,127,132]. For example, patients who attended primary care clinics who had higher ACIC scores had better managed diabetes as indicated by their haemoglobin A1C values than patients who attended primary care clinics with lower ACIC scores [121,122]. However, the ACIC survey only provides a generic assessment of the quality of chronic disease care. The ACIC captured less than 50% of organizational concepts identified by Levesque et al. [20] (Table 2; Fig. 2).

In addition to the ACIC survey, five American organizational attribute data collection tools were also developed based on the CCM, including the surveys used in the Translating Research into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) study 82–86, the National Survey of Physician Organizations and the Management of Chronic Illness 87–95, the Prescription for Independent Evaluation Surveys [96,97], Chronic Disease Prevention and Control Healthcare Practice Survey [98], and the Improving Chronic Illness Care Evaluation Survey [66]. There were two American data collection tools found that were developed to measure disease-specific primary care organizational attributes, namely, the surveys utilized within the TRIAD study 82–86 and the Primary Care Depression Management Organizational Survey [99].

Europe

Five primary care organizational attribute data collection tools from Europe met the selection criteria for inclusion in this study (Table 1). Three of these tools assessed organizational attributes that specifically related to diabetes care, namely, the questionnaires used within the Improving Quality of Care in Diabetes Study [108,140,141], the National Survey of the Provision of Diabetes Services [109,110] and the Survey of the Provision of Diabetes Services in Galway City and County [75,76]. The most commonly collected organizational attributes within the European tools were related to funding mechanisms, governance and administration, clinical processes, quality improvement, and patient safety mechanisms (Table 2). The WHO Primary Care Quality Management Tool [74,111] and the Survey of the Provision of Diabetes Services in Galway City and County [75,76] captured less than 40% of important organizational concepts [20] (Fig. 2).

Australia

Within Australia, the General Practice Chronic Care Team Profile [80,81,112,113] was the only organizational attribute data collection tool that was identified (Table 1). This structured interview schedule is designed to measure multidisciplinary teamwork structures and functions for chronic disease care in general practice, and takes approximately 15 minutes to complete. The tool is intended to be administered to a principal GP within a primary care setting or a practice manager. It is composed of questions that relate to team functions, non-GP clinical functions and staff management, administrative functions, and practice management structures. It reflects 32% of the organizational attributes identified in the classification system developed by Levesque et al. [20] (Fig. 2). The tool was developed by consulting best-practice guidelines for chronic disease care and performance standards for general practice in Australia and internationally, expert consultations to determine which items were relevant and suitable to be included in the interview schedule, and a pilot test within 11 general practices. Psychometric testing of the General Practice Chronic Care Team Profile identified that it has a Cronbach's alpha of 0.85.

Discussion

Patients with chronic diseases are most effectively managed within the primary care setting 5–8. To determine how to optimize the care for patients that have chronic diseases, it is important to investigate the heterogeneity in organizational attributes within primary care and assess the impact of these attributes on health outcomes within this patient population. This study identified a wide range of comprehensive primary care organizational attribute data collection tools that could feasibly be utilized by clinicians or scientists in this type of evaluation and research. Specifically, 30 organizational attribute data collection tools were identified in this systematic search and review. The review found that the tools varied with respect to overall focus and level of organizational details captured, theoretical foundations, administration and completion methods, length and types of questions asked, and the extent to which psychometric property testing has been completed. Each tool that was identified captures important information about primary care organizational attributes that could be used to better understand the delivery of chronic disease prevention and management within the primary care setting. Given the breadth of organizational attributes that were captured in the data collection tools, the variation between tools and the fact that many of the tools were developed for use within a specific jurisdiction, no one tool was found to be superior for all potential research and clinical applications. Many of the organizational attribute data collection tools identified have the potential to be used or adapted for use for different research purposes. The decision on which tool is most suitable will likely depend on the location in which the clinicians or researchers intend to conduct the research and the attributes in which they are interested in investigating.

It is important to note that several weaknesses with the tools were apparent. For example, not all of the data collection tools were based on existing theoretical frameworks, which may limit their applicability to the primary care setting or chronic disease management. Utilizing a framework to guide the development of a tool is important to help identify variables and understand the relationships between these variables [114]. Furthermore, the most common method of completion was the use of a paper-based postal questionnaire that relied on self-report from respondents and is often associated with low response rates [114]. In addition, many of the data collection tools that were identified were developed over a decade ago and may not accurately reflect current practices and organization within the primary care setting. Recently developed tools, such as the tool utilized within the QUALICOPC study that was implemented between 2010 and 2013 [30,31], and the Canadian Primary Healthcare Practice-Based Surveys that were recently developed and made available for use by researchers, clinicians and decision makers in April 2013 [56,57], are preferable for future studies assessing primary care organizational attributes.

Interestingly, most of the data collection tools that were identified were not disease specific. Only four tools were identified that were specifically developed to measure organizational attributes that related to diabetes care 75,76,82–86,108–110,140,141, and one tool was identified that specifically related to the management of patients with depression [99]. Instead, many of the data collection tools were designed to collect organizational attribute information that could be utilized to better understand the management of several chronic diseases and incorporated disease-specific questions, such as questions specifically related to diabetes, hypertension, asthma and/or cardiovascular disease. It is important to collect organizational attribute information that is related to multiple chronic diseases given that patients are often affected by more than one chronic condition [115].

Organizational attribute details captured by each tool varied substantially. The most commonly assessed attributes across all of the data collection tools were organizational environment and practice integration, human and technical resources, governance and administration, clinical processes, quality improvement and patient safety mechanisms, specific disease management practices, and degree of integration. The data collection tool that contained the most comprehensive description of primary care organizational attributes, as identified by the classification system developed by Levesque and colleagues [20], was the Canadian Primary Health Care Practice-Based Surveys [56,57]. This tool does not collect demographic characteristics of the population and patients served by a practice. However, it can be used in combination with its patient-level survey or linked to data from existing data sets that contain patient demographic details. Furthermore, unlike many of the tools that were identified in this study that were intended to measure attributes at a jurisdictional level, the Canadian Primary Health Care Practice-Based Surveys provide an opportunity to identify organizational attributes at a national level, and to make comparisons across different jurisdictions in Canada [56,57].

This review found only one organizational attribute data collection tool developed within Australia [80,81,112,113]. It is possible that fewer organizational attribute data collection tools have been developed in certain countries over the past decade because there are well-established data collection programmes already in place. For example, the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) programme has been used in Australia since 1998 to measure primary care organizational attributes, among other variables [116]. Researchers worldwide have been working towards establishing nationwide databases to monitor and evaluate the management of patients within a given population. Establishing a method to obtain national-level data within the primary care setting has become increasingly of interest to health care providers and researchers seeking to improve the quality of care delivered. There are several research networks that have been successful at conducting health surveillance research projects, such as the Clinical Practice Research Datalink in the United Kingdom [117], the European Practice Assessment [118], the Netherlands Information Network of General Practice [119] and the BEACH project in Australia [116].

The Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network (CPCSSN) is Canada's first and only chronic disease EMR surveillance system. It is an initiative established in 2008 that is funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada through a contribution agreement with the College of Family Physicians of Canada. One of the main purposes of CPCSSN is to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of primary health care delivery, and to improve patient and system outcomes across the country by creating a platform for research, surveillance and education. It is currently composed of 10 practice-based research networks across eight provinces in Canada. CPCSSN collects information on all clinical encounters for all patients visiting practices of sentinel physicians but is specifically focused on the following eight chronic conditions: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, epilepsy, parkinsonism, dementia, osteoarthritis, hypertension and diabetes [142,143]. The CPCSSN currently has a short questionnaire that is administered to primary care practices affiliated with their network to acquire general demographic information. To best inform quality improvement strategies, a more comprehensive organizational attribute data collection tool would allow us to determine the distribution and nature of primary care organizational attributes across Canada and those organizational attributes associated with optimal health outcomes of patients with chronic diseases.

Strengths and limitations

Despite utilizing a comprehensive search strategy [16], it is possible that there are primary care organizational attribute data collection tools that were not captured in this systematic search and review. Furthermore, reporting on the various elements of each tool was restricted to the extent to which information was available within the articles. Lack of data pertaining to the psychometric properties of the tools limited our ability to assess the quality of many of the organizational attribute data collection tools identified. In addition, two concepts from the classification system established by Levesque et al. [20] were excluded in this study as none or few studies included questions pertaining to them (i.e. sustainability and efficacy, readiness to change and capacity for adaptation) [20].

Despite the limitations associated with this study, the findings provide a thorough description of organizational attribute data collection tools that have been developed and/or used within the primary care setting worldwide. Systematic search and review methodology [16] was utilized to ensure that a complete list of organizational attribute data collection tools was found, and many of the tools that were identified were recent and widely used within the primary care setting. Furthermore, this study categorized the concept of ‘organizational human resources’ to identify the extent in which the tools captured information related to GPs, nurses and other health care or administrative staff within the practice. This review also highlights that there are different approaches to measuring organizational attributes within primary care. Researchers, primary care health care providers and stakeholder groups can use the findings from this study to obtain important information about primary care organizational structures and characteristics with the aim of improving the overall delivery of health care services for patients who have chronic diseases.

Conclusion

Thirty primary care organizational attribute data collections tools were identified in this systematic search and review that have been used in several countries worldwide. No single tool is recommended for use by clinicians or scientists as the decision on which tool to use or adapt will depend on the country of origin and the organizational attributes that are of most interest to capture in each study. The tool that was most recently developed and that captured the most organizational attributes was the Canadian Primary Health Care Practice-Based Surveys. Many of the tools that were identified have been used at a jurisdictional level. There is a need to collect organizational attribute information at a national level to better understand the management of chronic diseases across countries. Although there are existing databases in certain countries that collect information related to primary care organizational attributes, there is no existing platform in Canada. The data collection tools identified in this review can be used to assist countries in establishing a national-level data collection strategy to collect this important information that can be used to better understand the quality of chronic disease prevention and management.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Christina Godfrey, RN, PhD, and Sarah Wickett, BSc, MLIS, from Queen's University who provided invaluable support and guidance with this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web site.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

References

- 1.World Health Organization. 2011. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 2.Health Canada. 2013. Preventing chronic disease strategic plan 2013–2016. Available at: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cd-mc/diabetes-diabete/strategy_plan-plan_strategique-eng.php (last accessed 30 December 2013)

- 3.Health Canada. 2011. About primary health care. Available at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/prim/about-apropos-eng.php (last accessed 30 December 2013)

- 4.Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2012. Disparities in Primary Health Care Experiences among Canadians with Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions. Health Canada.

- 5.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH. Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(15):1909–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin SJ, Wagner E, van Eijk JT. Assendelft WJJ. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001481. CD001481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner EH, Austin BT. Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. The Milbank Quarterly. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canadian Diabetes Association. Canadian diabetes association 2013 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2013;37(Suppl. 1):S1–S212. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutchinson B, Levesque J, Cook B, Strumpf E. Coyle N. Primary health care in Canada: systems in motion. The Milbank Quarterly. 2011;89(2):256–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett J, Curran V, Glynn L. Goodwin M. 2007. CHSRF synthesis: interprofessional collaboration and quality primary healthcare. Available at: http://www.chsrf.ca (last accessed 30 December 2013)

- 11.Hogg W, Dahrouge S, Russell G, Tuna M, Geneau R, Muldoon L, Kristjansson E. Johnston S. Health promotion activity in primary care: performance of models and associated factors. Open Medicine. 2009;3(3):e165–e173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell G, Dahrouge S, Tuna M, Hogg W, Geneau R. Gebremichael G. Getting it all done. Organizational factors linked with comprehensive primary care. Family Practice. 2010;27(5):535–541. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell GM, Dahrouge S, Hogg W, Geneau R, Muldoon L. Tuna M. Managing chronic disease in Ontario primary care: the impact of organizational factors. Annals of Family Medicine. 2009;7(4):309–318. doi: 10.1370/afm.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahrouge S, Hogg W, Russell G, Tuna M, Geneau R, Muldon L, Kristjansson E. Fletcher K. Impact of remuneration and organizational factors on completing preventive manoeuvres in primary care practices. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2012;184(2):E135–E143. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liddy C, Singh J, Hogg W, Dahrouge S. Taljaard M. Comparison of primary care models in the prevention of cardiovascular disease – a cross sectional study. BMC Family Practice. 2011;12(1):114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant M. Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal. 2009;26(91):91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Cochrane Collaboration. 2013. The Cochrane Library. Available at: http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/view/0/index.html (last accessed 30 December 2013)

- 18.The Joanna Briggs Institute. 2013. Systematic review registered titles. Available at: http://joannabriggs.org/index.html (last accessed 30 December 2013)

- 19.Hogg W, Rowan M, Russell G, Geneau R. Muldoon L. Framework for primary care organizations: the importance of a structural domain. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care/ISQua. 2008;20(5):308–313. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levesque JF, Descoteaux S, Demers N. Benigeri M. 2012. Measuring organizational attributes of primary care: a review and classification of measurement items used in international questionnaires. Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ)

- 21.Malouin RA, Starfield B. Sepulveda MJ. Evaluating the tools used to assess the medical home. Managed Care. 2009;18(6):44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhydderch M, Edwards A, Elwyn G, Marshall M, Engels Y, Van den Hombergh P. Grol R. Organizational assessment in general practice: a systematic review and implications for quality improvement. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2005;11(4):366–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2005.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Commissaire a la Sante et au Bien-etre. 2009. Primary care doctors' views and experiences: how Quebec compares. Results from the 2009 Commonwealth Fund International Survey of Primary Care Doctors. Quebec: Commissaire a la sante et au bien-etre.

- 24.Davis K, Doty MM, Shea K. Stremikis K. Health information technology and physician perceptions of quality of care and satisfaction. Health Policy. 2009;90(2–3):239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty M, Rasmussen P, Pierson R. Applebaum S. A survey of primary care doctors in ten countries shows progress in use of health information technology, less in other areas. Health Affairs. 2012;31(12):2805–2816. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoen C, Osborn R, Doty MM, Squires D, Peugh J. Applebaum S. A survey of primary care physicians in eleven countries, 2009: perspectives on care, costs, and experiences. Health Affairs. 2009;28(6):W1171–W1183. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoen C, Osborn R, Huynh PT, Doty M, Peugh J. Zapert K. On the front lines of care: primary care doctors' office systems, experiences, and views in seven countries. Health Affairs. 2006;25(6):W555–W571. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.w555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Commonwealth Fund. News release: international survey of primary care physicians in 11 countries reveals U.S. lagging in access, quality, and use of health information technology; underscores urgent need for national health reform. Health Affairs. 2009:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Commonwealth Fund. News release: new international survey of primary care physicians: most U.S. doctors unable to provide patients access to after-hours care; half lack access to drug safety alert systems. Health Affairs. 2006:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schafer WL, Boerma WG, Kringos DS, et al. Measures of quality, costs and equity in primary health care: instruments developed to analyse and compare primary health care in 35 countries. Quality in Primary Care. 2013;21(2):67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schäfer WLA, Van den Berg MJ, Vainieri M, et al. QUALICOPC, a multi-country study evaluating quality, costs and equity in primary care. BMC Family Practice. 2011;12:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kringos DS, Boerma WGW, Spaan E. Pellny M. A snapshot of the organization and provision of primary care in Turkey. BMC Health Services Research. 2011;11:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. 2012. Evaluation of the structure and provision of primary care in Slovakia. A survey based project. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 34.World Health Organization. 2012. Evaluation of the structure and provision of primary care in the republic of Moldova. A survey-based project. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 35.World Health Organization. 2012. Evaluation of the structure and provision of primary care in Romania. A survey-based project. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 36.World Health Organization. 2011. Evaluation of the structure and provision of primary care in Kazakhstan. A survey-based project in the regions of Almaty and Zhambyl. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 37.World Health Organization. 2010. Evaluation of the structure and provision of primary care in Serbia. A survey-based project in the regions of Vojvodina, Central Serbia and Belgrade. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 38.World Health Organization. 2010. Evaluation of structure and provision of primary care in Ukraine. A survey-based project in the regions of Kiev and Vinnitsa. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 39.World Health Organization. 2009. Evaluation of the structure and provision of primary care in Belarus. A survey-based project in the regions of Minsk and Vitebsk. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 40.World Health Organization. 2008. Evaluation of the organizational model of primary care in Turkey. A survey-based pilot project in two provinces of Turkey. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 41.World Health Organization. 2008. Evaluation of the organizational model of primary care in the Russian federation. A survey-based pilot project in two rayons of Moscow oblast. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 42.Campbell DJT, Sargious P, Lewanczuk R, McBrien K, Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B. Manns B. Use of chronic disease management programs for diabetes: in Alberta's primary care networks. Canadian Family Physician. 2013;59(2):e86–e92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rondeau KV. Bell NR. The chronic care model: which physician practice organizations adapt best? Healthcare Management Forum. 2009;22(4):31–39. doi: 10.1016/S0840-4704(10)60140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dahrouge S, Hogg W, Russell G, Geneau R, Kristjansson E, Muldoon L. Johnston S. The comparison of models of primary care in Ontario (COMP-PC) study: methodology of a multifaceted cross-sectional practice-based study. Open Medicine. 2009;3(3):e149–e164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayo-Bruinsma L. 2011. Family-centered care delivery: comparing models of primary care service delivery in Ontario [Thesis]. Ottawa: University of Ottawa.

- 46.Muldoon L, Dahrouge S, Hogg W, Geneau R, Russell G. Shortt M. Community orientation in primary care practices: results from the comparison of models of primary health care in Ontario study. Canadian Family Physician. 2010;56(7):676–683. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnsley J, Williams AP, Kaczorowski J, Vayda E, Vingilis E, Campbell A. Atkin K. Who provides walk-in services? Survey of primary care practices in Ontario. Canadian Family Physician. 2002;48:519–526. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lemieux V, Lévesque J. Ehrmann-Feldman D. Are primary healthcare organizational attributes associated with patient self-efficacy for managing chronic disease? Healthcare Policy. 2011;6(4):e89–e105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levesque J, Pineault R, Provost S, Tousignant P, Couture A, Da Silva RB. Breton M. Assessing the evolution of primary healthcare organizations and their performance (2005–2010) in two regions of Québec province: Montréal and Montérégie. BMC Family Practice. 2010;11:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pineault R. Are the profile and type of organization of primary care linked to experience of care for their clients? Findings of a study in two regions of Québec. Thema. 2007;4(1):2–6. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pineault R, Provost S, Hamel M, Couture A. Levesque JF. The influence of primary health care organizational models on patients' experience of care in different chronic disease situations. Chronic Diseases and Injuries in Canada. 2011;31(3):109–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pineault R, Levesque J, Roberge D, Hamel M, Lamarche P. Haggerty J. 2009. Accessibility and continuity of care: a study of primary healthcare in Québec: research report presented to the Canadian institutes of health research (CIHR) and the Canadian health services research foundation (CHSRF). Quebec: Gouvernement du Quebec.

- 53.Provost S, Pineault R, Tousignant P, Hamel M. Da Silva RB. Evaluation of the implementation of an integrated primary care network for prevention and management of cardiometabolic risk in Montréal. BMC Family Practice. 2011;12:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haggerty J, Pineault R, Beaulieu M, Brunelle Y, Goulet F, Rodrigue J. Gauthier J. 2004. Accessibility and continuity of primary care in Québec. Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation.

- 55.Pyra Management Consulting Services Inc; Research Power Incorporated. 2006. A Primary Health Care Evaluation System for Nova Scotia. Pyra Management Consulting Services Inc. & Research Power Incorporated.

- 56.Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2013. About primary health care practice-based surveys. Available at: http://www.cihi.ca/CIHI-ext-portal/internet/en/tabbedcontent/types+of+care/primary+health/cihi006583 (last accessed 30 December 2013)

- 57.Johnston S. Burge F. 2013. Measuring Provider Experiences in Primary Health Care. Report on the Development of a PHC Provider Survey for the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Ottawa: Bruyère Research Institute.

- 58.Bailie R, Si D, Connors C, et al. Study protocol: audit and best practice for chronic disease extension (ABCDE) project. BMC Health Services Research. 2008;17(8):184. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bailie R, Si D, Dowden M, O'Donoghue L, Connors C, Robinson G, Cunningham J. Weeramanthri T. Improving organisational systems for diabetes care in Australian indigenous communities. BMC Health Services Research. 2007;7(1):67. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barcelo A, Cafiero E, De Boer M, et al. Using collaborative learning to improve diabetes care and outcomes: the VIDA project. Primary Care Diabetes. 2010;4(3):145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bonomi AE, Wagner EH, Glasgow RE. VonKorff M. Assessment of chronic illness care (ACIC): a practical tool to measure quality improvement. Health Services Research. 2002;37(3):791–820. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bosch M, van der Weijden T, Grol R, Schers H, Akkermans R, Niessen L. Wensing M. Structured chronic primary care and health-related quality of life in chronic heart failure. BMC Health Services Research. 2009;9:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cramm JM. Nieboer AP. Disease-management partnership functioning, synergy and effectiveness in delivering chronic-illness care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care/ISQua. 2012;24(3):279–285. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzs004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cramm JM, Nieboer AP, Tsiachristas A. Strating MMH. Development and validation of a short version of the assessment of chronic illness care (ACIC) in Dutch disease management programs. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2011;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cramm JM. Nieboer AP. Relational coordination promotes quality of chronic care delivery in Dutch disease-management programs. Health Care Management Review. 2012;37(4):301–309. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182355ea4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cretin S, Shortell SM. Keeler EB. An evaluation of collaborative interventions to improve chronic illness care. Framework and study design. Evaluation Review. 2004;28(1):28–51. doi: 10.1177/0193841X03256298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feifer C, Ornstein SM, Nietert PJ. Jenkins RG. System supports for chronic illness care and their relationship to clinical outcomes. Topics in Health Information Management. 2001;22(2):65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gomutbutra P, Aramrat A, Sattapansri W, Chutima S, Tooprakai D, Sakarinkul P. Sangkhasilapin Y. Reliability and validity of a Thai version of assessment of chronic illness care (ACIC) Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2012;95(8):1105–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaissi AA. Parchman M. Organizational factors associated with self-management behaviors in diabetes primary care clinics. The Diabetes Educator. 2009;35(5):843–850. doi: 10.1177/0145721709342901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kaissi AA. Parchman M. Assessing chronic illness care for diabetes in primary care clinics. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2006;32(6):318–323. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lemmens KMM, Nieboer AP, Rutten-Van Mölken MP, van Schayck C, Spreeuwenberg C, Asin JD. Huijsman R. Bottom-up implementation of disease-management programmes: results of a multisite comparison. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2011;20:76–86. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leykum LK, Palmer R, Lanham H, Jordan M, McDaniel RR, Noel PH. Parchman M. Reciprocal learning and chronic care model implementation in primary care: results from a new scale of learning in primary care. BMC Health Services Research. 2011;11:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Parchman ML, Zeber JE, Romero RR. Pugh JA. Risk of coronary artery disease in type 2 diabetes and the delivery of care consistent with the chronic care model in primary care settings: a STARNet study. Medical Care. 2007;45(12):1129–1134. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318148431e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.World Health Organization. 2008. Primary care quality management in Slovenia. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 75.Evans DS, O'Connell E, O'Donnell M, Hurley L, Glacken M, Murphy A. Dinneen SF. 2009. The Provision of General Practice Diabetes Services in Galway City and County: a Survey of General Practice. Galway Health Service Executive West.

- 76.Evans DS, O'Connell E, O'Donnell M, Hurley L, Glacken M, Murphy AW. Dinneen SF. The current state of general practice diabetes care in the west of Ireland. Practical Diabetes International. 2009;26(8):322–325. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Darker C, Martin C, O'Dowd T, O'Kelly F, O'Kelly M. O'Shea B. 2011. A National Survey of Chronic Disease Management in Irish General Practice. Dublin Department of Public Health and Primary Care.

- 78.Darker C, Martin C, O'Dowd T, O'Kelly F. O'Shea B. Chronic disease management in general practice: results from a national study. Irish Medical Journal. 2012;105(4):102–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pearson ML, Keeler EB, Wu S, Schaefer J, Bonomi AE, Shortell SM, Mendel PJ, Marsteller JA, Louis TA. Rosen M. Assessing the implementation of the chronic care model in quality improvement collaboratives. BMC Health Services Research. 2005;40(4):978–996. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Black DA, Taggart J, Jayasinghe UW, Proudfoot J, Crookes PA, Beilby J, Powell-Davis G, Wilson LA. Harris MF. The teamwork study: enhancing the role of non-GP staff in chronic disease management in general practice. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2012;19(3):184–189. doi: 10.1071/PY11071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chan B, Proudfoot J, Zwar N, Davies GP. Harris MF. Satisfaction with referral relationships between general practice and allied health professionals in Australian primary health care. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2011;17(3):250–258. doi: 10.1071/PY10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.TRIAD Study Group. Health systems, patient factors, and quality of care for diabetes: a synthesis of findings from the TRIAD study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(4):940–947. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Duru OK, Gerzoff RB, Huh S, et al. The association between clinical care strategies and the attenuation of racial/ethnic disparities in diabetes care: the translating research into action for diabetes (TRIAD) study. Medical Care. 2006;44(12):1121–1128. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000237423.05294.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Malik S. 2005. Impact of organizational factors on cardiovascular disease processes and outcomes in persons with diabetes in managed care [Thesis]. Los Angeles: University of California.

- 85.Mangione CM, Gerzoff RB, Williamson DF, et al. The association between quality of care and the intensity of diabetes disease management programs. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145(2):107–116. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-2-200607180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.TRIAD Study Group. The translating research into action for diabetes (TRIAD) study: a multicenter study of diabetes in managed care. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(2):386–389. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shortell SM, Schmittdiel J, Wang MC, Li R, Gillies RR, Casalino LP, Bodenheimer T. Rundall TG. An empirical assessment of high-performing medical groups: results from a national study. Medical Care Research and Review. 2005;62(4):407–434. doi: 10.1177/1077558705277389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schmittdiel J, Bodenheimer T, Solomon NA, Gillies RR. Shortell SM. Brief report: the prevalence and use of chronic disease registries in physician organizations: a national survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20(9):855–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schmittdiel JA, McMenamin SB, Halpin HA, Gillies RR, Bodenheimer T, Shortell SM, Rundall T. Casalino LP. The use of patient and physician reminders for preventative services: results from a national study of physician organizations. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39(5):1000–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schmittdiel JA, Shortell SM, Rundall TG, Bodenheimer T. Selby JV. Effect of primary health care orientation on chronic care management. Annals of Family Medicine. 2006;4(2):117–123. doi: 10.1370/afm.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li R, Simon J, Bodenheimer T, Gillies RR, Casalino L, Schmittdiel J. Shortell SM. Organizational factors affecting the adoption of diabetes care management processes in physician organizations. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(10):2312–2316. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ovretveit J, Gillies R, Rundall TG, Shortell SM. Brommels M. Quality of care for chronic illnesses. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance. 2008;21(2):190–202. doi: 10.1108/09526860810859049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McMenamin SB, Schmittdiel J, Halpin HA, Gillies R, Rundall TG. Shortell SM. Health promotion in physician organizations: results from a national study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26(4):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gillies RR, Shortell SM, Casalino L, Robinson JC. Rundall TG. How different is California? A comparison of U.S. physician organizations. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2003;W3:492–502. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w3.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Casalino L, Wang MC, Gillies RR, Shortell SM, Schmittdiel JA, Bodenheimer T, Robinson JC, Rundall T, Oswald N. Schauffler H. External incentives, information technology, and organized processes to improve health care quality for patients with chronic diseases. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(4):434–441. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hung DY, Rundall TG, Crabtree BF, Tallia AF, Cohen DJ. Halpin HA. Influences of primary care practice and provider attributes on preventative service delivery. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30(5):413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hung DY, Glasgow RE, Dickinson LM, Froshaug DB, Fernald DH, Balasubramanian BA. Green LA. The chronic care model and relationships to patient health status and health-related quality of life. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35(Suppl. 5):S398–S406. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tran N. Dilley JA. Achieving a high response rate with a health care provider survey, Washington state, 2006. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2010;7(5):A111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Post EP, Kilbourne AM, Bremer RW, Solano FX, Jr, Pincus HA. Reynolds CF., 3rd Organizational factors and depression management in community-based primary care settings. Implementation Science. 2009;4:84. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kralewski JE, Dowd BE, Heaton A. Kaissi A. The influence of the structure and culture of medical group practices on prescription drug errors. Medical Care. 2005;43(8):817–825. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000170419.70346.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lowe RA, Feldman HI, Localio AR, Schwarz DF, Williams S, Tuton LW, Maroney S, Nicklin D, Goldfarb N. Vojta DD. Association between primary care practice characteristics and emergency department use in a Medicaid managed care organization. Medical Care. 2005;43(8):792–800. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000170413.60054.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Macinko J, Almeida C. de Sá PK. A rapid assessment methodology for the evaluation of primary care organization and performance in Brazil. Health Policy and Planning. 2007;22(3):167–177. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czm008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Macinko J, Almeida C, dos SE. de Sá PK. Organization and delivery of primary health care services in Petrópolis, Brazil. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2004;19(4):303–317. doi: 10.1002/hpm.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Starfield B. Shi L. Policy relevant determinants of health: an international perspective. Health Policy. 2002;60(3):201–218. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(01)00208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stigler FL, Starfield B, Sprenger M, Salzer HJ. Campbell SM. Assessing primary care in Austria: room for improvement. Family Practice. 2013;30(2):185–189. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pasarin MI, Berra S, Gonzalez A, Segura A, Tebe C, Garcia-Altes A, Vallverdu I. Starfield B. Evaluation of primary care: the ‘primary care assessment tools – facility version’ for the Spanish health system. Gaceta Sanitaria. 2013;27(1):12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Starfield B, Cassady C, Nanda J, Forrest CB. Berk R. Consumer experiences and provider perceptions of the quality of primary care: implications for managed care. The Journal of Family Practice. 1998;46(3):216–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Eccles MP, Hrisos S, Francis JJ, et al. Instrument development, data collection, and characteristics of practices, staff, and measures in the Improving Quality of Care in Diabetes (iQuaD) Study. Implementation Science. 2011;6:1–21. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mc Hugh S, O'Keeffe J, Fitzpatrick A, de Siun A, O'Mullane M, Perry I. Bradley C. Diabetes care in Ireland: a survey of general practitioners. Primary Care Diabetes. 2009;3(4):225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Williams DRR, Baxter HS, Airey CM, Ali S. Turner B. Diabetes UK funded surveys of the structural provision of primary care diabetes services in the UK. Diabetic Medicine: A Journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2002;19(Suppl. 4):21–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.19.s4.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.World Health Organization. 2008. Primary care quality management in Uzbekistan. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 112.Harris MF, Jayasinghe UW, Taggart J, Christl B, Proudfoot JG, Crookes PA, Beilby JJ. Davies GP. Multidisciplinary team care arrangements in the management of patients with chronic disease in Australian general practice. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2011;194(5):236–239. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb02952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Proudfoot JG, Bubner T, Amoroso C, Swan E, Holton C, Winstanley J, Beilby J. Harris MF. Chronic care team profile: a brief tool to measure the structure and function of chronic care teams in general practice. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2009;15(4):692–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Polit DE. Beck CT. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 8th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. 2007. Preventing and Managing Chronic Disease: Ontario's Framework. Ontario: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

- 116.Family Medicine Research Centre, The University of Sydney. 2013. Bettering the evaluation and care of health (BEACH). Available at: http://sydney.edu.au/medicine/fmrc/beach/index.php (last accessed 30 December 2013)

- 117.National Institute for Health Research. 2013. Clinical practice research datalink. Available at: http://www.cprd.com/home/ (last accessed 30 December 2013)

- 118.TOPAS Europe. 2008. European practice assessment – EPA. Easy to use and scientifically developed quality management for general practice. Available at: http://www.topaseurope.eu/files/EPA-Information-Paper-English-vs11_0.pdf (last accessed 30 December 2013)

- 119.Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research. 2013. Netherlands information network of general practice (LINH). Available at: http://www.nivel.nl/en/netherlands-information-network-general-practice-linh (last accessed 30 December 2013)

- 120.Friedberg MW, Coltin KL, Safran DG, Dresser M, Zaslavsky AM. Schneider EC. Associations between structural capabilities of primary care practices and performance on selected quality measures. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151(7):456–463. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-7-200910060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Parchman M. Kaissi AA. Are elements of the chronic care model associated with cardiovascular risk factor control in type 2 diabetes? Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2009;35(3):133–138. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]