Abstract

Rationale: Disability guidelines are often based on pulmonary function testing, but factors other than lung function influence how an individual experiences physiologic impairment. Age may impact the perception of impairment in adults with chronic lung disease.

Objectives: To determine if self-report of physical functional impairment differs between older adults with chronic lung disease compared with younger adults with similar degrees of lung function impairment.

Methods: The Lung Tissue Research Consortium provided data on 981 participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and interstitial lung disease who were well characterized with clinical, radiological, and pathological diagnoses. We used multiple logistic regression to determine if responses to health status questions (from the Short Form-12 and St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire) related to perception of impairment differed in older adults (age ≥ 65 yr, n = 427) compared with younger adults (age < 65 yr, n = 393).

Measurements and Main Results: Pulmonary function was higher in older adults (median FEV1 %, 70) compared with younger adults (median FEV1 %, 62) (P < 0.001), whereas the median 6-minute-walk distance was similar between groups (372 m vs. 388 m, P = 0.21). After adjusting for potential confounders, older adults were less likely to report that their health limited them significantly in performing moderate activities (odds ratio [OR], 0.36; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.22–0.58) or climbing several flights of stairs (OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.34–0.77). The odds of reporting that their physical health limited the kinds of activities they performed were reduced by 63% in older adults (OR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.24–0.58), and, similarly, the odds of reporting that their health caused them to accomplish less than they would like were also lower in older adults (OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.25–0.60). The OR for reporting that their breathing problem stops them from doing most things or everything was 0.35 (95% CI, 0.22–0.55) in older adults versus younger adults.

Conclusions: Older adults with chronic lung disease were less likely to report significant impairment in their activities compared with younger adults, suggesting they may perceive less limitation.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, quality of life, interstitial lung diseases, aged, respiratory function tests

Objective measures of physiologic impairment are often used as surrogates for functional limitation to define disability. However, patients with chronic lung disease with similar impairment in lung function may have varying degrees of functional limitation. Several factors may influence how an individual experiences their physiologic impairment, including comorbid disease, socioeconomic status, and social support. Some evidence suggests that age may modify how an individual perceives their impairment and resultant functional limitation, with older adults tending to be more optimistic about their health (1–3).

The Lung Tissue Research Consortium (LTRC) (http://www.ltrcpublic.com) is a multicenter research initiative that collects lung tissue from patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for research. Participants in the LTRC include both young and old individuals, with an age range of 23 to 91 years. Before tissue collection, LTRC participants are characterized according to radiographic abnormalities, physiologic impairment, medical history, and assessment of health status. Their pulmonary diagnosis is supported by histologic confirmation after tissue collection. Thus, the LTRC dataset is ideal for studying the relationships between physiologic impairment and perceived functional status in patients with well-defined lung disease. Accordingly, we compared responses to health status questionnaires from older and younger adults with chronic lung diseases.

The major objective of this study was to determine if the perception of functional limitation differs between older adults and younger adults with similar degrees of impairment in pulmonary function due to chronic lung disease. Some of these results have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (4).

Methods

Study Participants

The LTRC began enrolling patients with ILD or COPD in September 2005. The dataset used for this analysis includes patients from four clinical centers: Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN), University of Colorado (Aurora, CO), University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI), and University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, PA). All participants provided written informed consent, and local institutional review board approval was obtained. The LTRC inclusion criteria are 21 years of age or older and one of the following clinical indications for lung tissue acquisition: (1) diagnosis of ILD leading to surgical biopsy, (2) diagnosis of COPD leading to lung volume reduction surgery, (3) diagnosis of ILD or COPD in patients listed for lung transplantation, or (4) lung nodule or mass requiring surgical resection. Surgical procedures are selected using standard clinical indications by the medical providers caring for the patients. Exclusion criteria are: (1) an active primary infectious process; or (2) a diagnosis of cystic fibrosis, berylliosis, or pulmonary hypertension as the indication for transplantation.

As of October 2009, 981 records were identified in the LTRC database for patients with a major clinical diagnosis of ILD (n = 405) or COPD (n = 576). Each clinical center’s principal investigator determined this diagnosis after reviewing local clinical and pathological data and reports from the LTRC Tissue Core (University of Colorado) and the LTRC Radiology Core (Mayo Clinic).

Data Collection

Demographic data and medical history were obtained by interview and written questionnaire. Health status surveys were administered in written format, including the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12 (SF-12) (5, 6). SGRQ is a validated questionnaire to assess disease impact that was originally developed for use in patients with COPD but has also been validated among patients with ILD (7–14). SF-12 is a generic measure of overall health status that has been correlated with lung function in COPD and has previously been examined in patients with interstitial lung disease in the LTRC cohort (11, 15–18). Pulmonary function testing was performed according to American Thoracic Society standards, including spirometry, assessment of diffusing capacity (DlCO), and measurement of 6-minute-walk distance (6MWD) (19–21). All data were obtained before tissue collection.

Statistical Analysis

The primary goal of this analysis was to compare responses to health status questionnaires among older adults (age ≥ 65 yr) and younger adults (age < 65 yr). Questions related to health status and functional limitation were selected from the SGRQ and SF-12 instruments, and a binary outcome was generated for each question (see Table E1 in the online supplement). Because older individuals are typically excluded from transplantation, the analysis was restricted to participants who did not undergo lung transplantation (n = 820).

Descriptive characteristics of older adults versus younger adults were compared using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. The associations between health status survey scores (SGRQ and SF-12) and age group were examined using multiple linear regression to adjust for potential confounders.

Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between age group and the outcome of interest, which was a response indicating significant perceived impairment to questions about health status and functional limitation. Multiple logistic regression was used to adjust for potential confounders of the relationship between age group and the outcome of interest, including race, sex, body mass index (BMI), pulmonary disease diagnosis, lung function (FEV1 %, FVC %, DlCO %), and 6MWD. The linearity assumption of logistic regression was verified for continuous variables including age by plotting the log odds of outcome versus quintile midpoints and using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing. BMI did not exhibit a linear relationship with the log odds of outcome, so BMI was converted to a categorical variable. P values for logistic regression coefficients were obtained using the Wald test or the likelihood ratio test. For each model, goodness-of-fit was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, and collinearity was assessed by determining the variance inflation factor for the explanatory variables. All data analysis was performed using Stata, version 11 (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

Missing Data

Among the 820 individuals eligible for inclusion in this study, 599 participants had complete data for all analyses. 6MWD was unavailable for 149 patients, DlCO measurements were unavailable for 35 patients, and both DlCO and 6MWD were unavailable for 32 patients. SF-12 scores were unavailable for five additional patients. No attempts were made to impute missing data.

Participants with missing data were not different from those with complete data with respect to age, sex, BMI, lung function, or pulmonary diagnosis. Participants with missing data were more likely to have a cancer diagnosis compared with those with complete data (37.0 vs. 27.9%, P = 0.01), but there was no difference with respect to other comorbidities. Overall, the proportion of white participants was similar between those with missing data and those with complete data, but the distribution of nonwhite participants differed (P = 0.002). Hispanic participants were more likely to have missing data (60% missing, total n = 10), and African-American participants were more likely to have complete data (3.6% missing, total n = 28).

Results

Characteristics of Older Adults versus Younger Adults in LTRC

Overall, there were 427 individuals 65 years of age and older and 393 individuals less than 65 years of age included in this study. The older group was composed of a greater proportion of men (n = 243, 56.9%) compared with the younger group (n = 183, 46.6%). Patients in both age groups were predominantly white, but there was statistically greater diversity with respect to race and ethnicity among the younger group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of older adults and younger adults in the Lung Tissue Research Consortium

| Variable | Age ≥ 65 yr | Age < 65 yr | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 427 | 393 | |

| Age, yr | 70 (67–75) | 58 (52–61) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 243 (56.9) | 183 (46.6) | 0.003 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.5 (24.2–31.3) | 28.3 (24.0–32.1) | 0.32 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 415 (97.2) | 355 (90.3) | 0.003 |

| African American | 7 (1.6) | 21 (5.3) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (0.5) | 8 (2.0) | |

| Other | 3 (0.7) | 9 (2.4) | |

| Comorbid disease | |||

| Angina | 55 (12.9) | 43 (11.0) | 0.39 |

| Heart failure | 45 (10.6) | 20 (5.1) | 0.004 |

| Diabetes | 59 (13.9) | 52 (13.3) | 0.81 |

| Renal failure | 15 (3.5) | 7 (1.8) | 0.13 |

| Cancer | 169 (39.7) | 79 (20.2) | <0.001 |

| Rheumatologic | 40 (9.4) | 37 (9.4) | 0.98 |

| Cirrhosis | 4 (0.9) | 5 (1.3) | 0.65 |

| HIV | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | 0.63 |

| Major diagnosis | |||

| ILD | 144 (33.7) | 194 (49.4) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 283 (66.3) | 199 (50.6) | |

| Spirometry | |||

| FEV1, % predicted | 70 (53–83) | 62 (39–77) | <0.001 |

| FVC, % predicted | 77 (64–90) | 69 (58–83) | <0.001 |

| DlCO, % predicted | 64 (51–83) | 62 (48–81) | 0.11 |

| 6MWD, m | 372 (312–426) | 388 (305–445) | 0.21 |

| Tissue collection | |||

| Lobectomy/wedge resection | 228 (53.4) | 127 (32.3) | <0.001 |

| Lung biopsy | 139 (32.6) | 160 (40.7) | |

| LVRS | 33 (7.7) | 51 (13.0) | |

| Not performed | 27 (6.3) | 55 (14.0) | |

| SS disability qualification | 154 (36.1) | 141 (35.9) | 0.96 |

| Missing data elements | 116 (27.2) | 105 (26.7) | 0.89 |

Definition of abbreviations: 6MWD = 6-minute-walk distance; BMI = body mass index; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DlCO = diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; ILD = interstitial lung disease; LVRS = lung volume reduction surgery; SS = social security.

Categorical data are presented as n (%) and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Continuous data are presented as median (interquartile range) and compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. FEV1 and FVC % predicted were calculated using the Hankinson equations. DlCO % predicted was determined by calculating predicted total lung capacity using equations for vital capacity and residual volume from Goldman and Becklake and then multiplying this by the ratio of single breath diffusing capacity to alveolar volume derived from the data of Burrows.

The major clinical diagnosis was COPD for the majority of older adults (66.3%), whereas it was divided evenly between COPD (50.6%) and ILD (49.4%) for the younger group. With respect to comorbid diseases, heart failure and cancer were more common among the older adults. The indication for tissue collection differed by age group, with a larger proportion of older adults undergoing lobectomy or wedge resection compared with younger adults (54.3% vs. 32.3%).

Lung function was higher in the group of older adults, including FEV1 % predicted (median, 70 vs. 62%; P < 0.001) and FVC % predicted (median, 77 vs. 69%; P < 0.001) as well as absolute measures of FEV1 and FVC. However, the proportion of individuals who would qualify for social security disability based on their pulmonary function did not differ by age group (36.1 vs. 35.9%, P = 0.96). 6MWD also did not differ significantly by age group (median, 372 m vs. 388 m; P = 0.21).

SGRQ and SF-12 Scores in Older Adults versus Younger Adults

Total SGRQ scores were lower among older adults compared with younger adults (median, 29.8 vs. 46.2; P < 0.0001), indicating better health status in the older group. Likewise, SF-12 physical component summary (PCS) scores and SF-12 mental component summary (MCS) scores were higher for older adults (median PCS, 42.0 vs. 36.2; P < 0.0001; median MCS, 54.2 vs. 50.1; P < 0.0001), again denoting better health status. Even after adjusting for potential confounders, older adults still had scores on average that reflected better health status compared with younger adults (Table 2).

Table 2.

Difference* in health status scores between older adults (age ≥ 65 yr) and younger adults with chronic lung disease

| Health Status Score | Age ≥ 65 yr | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SGRQ | −6.5 | −9.5, -3.5 | <0.001 |

| SF-12 PCS | +3.5 | 1.9, 5.1 | <0.001 |

| SF-12 MCS | +3.5 | 1.7, 5.3 | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: 6MWD = 6-minute-walk distance; BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; DlCO = diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; MCS = mental component summary; PCS = physical component summary; SF-12 = Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12; SGRQ = St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

N = 604 for SGRQ score and N = 599 for SF-12 scores.

Adjusted for sex, race, BMI, diagnosis, FEV1, FVC, DlCO %, and 6MWD.

Perception of Health Status and Functional Limitation among Older Adults

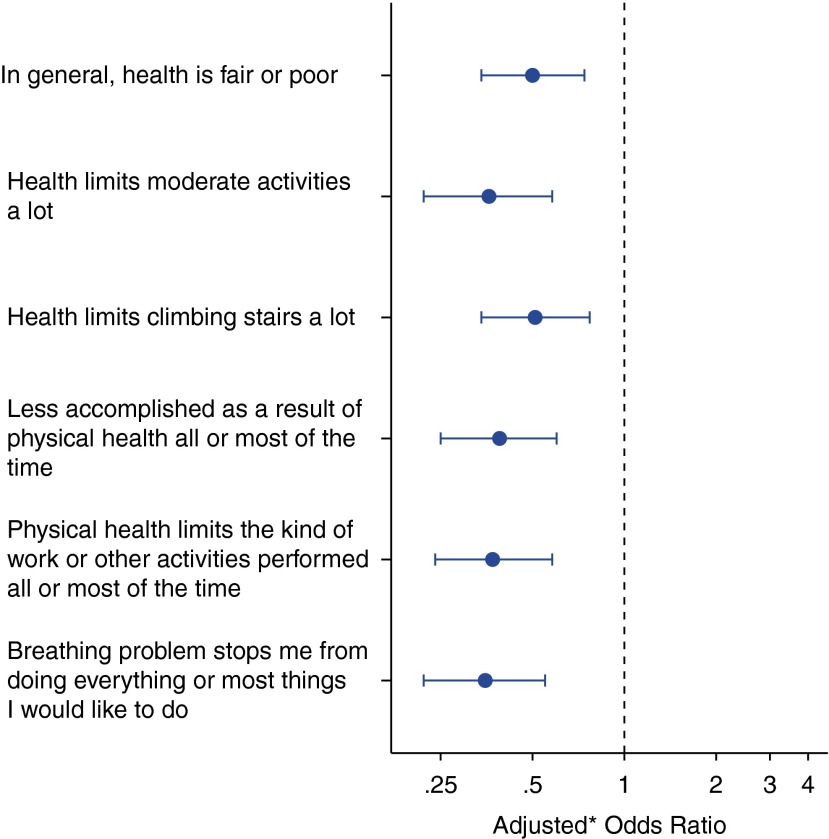

In response to specific questions about health status and physical functioning, older adults were less likely to report significant impairment compared with younger adults. After adjusting for potential confounders, including objective measures of physical functional status (6MWD) and physiologic impairment (FEV1 %, FVC %, DlCO %), these differences persisted (Table 3). For example, the odds of reporting their general health status as fair or poor were 50% lower in older adults compared with younger adults (OR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.34–0.74). Older adults were also less likely to report that their health limits them significantly in performing moderate activities (OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.22–0.58) or climbing several flights of stairs (OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.34–0.77).

Table 3.

Relative odds of response indicating perception of significant limitation in older adults versus younger adults with chronic lung disease

| Perception | OR | 95% CI | P Value* | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In general, health is fair or poor | 0.61 | 0.45, 0.81 | 0.001 | 0.50 | 0.34, 0.74 | 0.0006 |

| Health limits moderate activities a lot | 0.46 | 0.34, 0.62 | <0.001 | 0.36 | 0.22, 0.58 | <0.0001 |

| Health limits climbing stairs a lot | 0.50 | 0.38, 0.66 | <0.001 | 0.51 | 0.34, 0.77 | 0.001 |

| Less accomplished as a result of physical health all or most of the time | 0.42 | 0.32, 0.57 | <0.001 | 0.39 | 0.25, 0.60 | <0.0001 |

| Physical health limits the kind of work or other activities performed all or most of the time | 0.42 | 0.32, 0.57 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.24, 0.58 | <0.0001 |

| Breathing problem stops me from doing everything or most things I would like to do | 0.36 | 0.26, 0.48 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 0.22, 0.55 | <0.0001 |

Definition of abbreviations: 6MWD = 6-minute-walk distance; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

N = 599. ORs indicate relative odds of response indicating significant perceived impairment in older adults versus younger adults. Adjusted OR is adjusted for sex, race, diagnosis, body mass index, FEV1 % predicted, FVC % predicted, diffusing capacity %, and 6MWD.

Wald test.

Likelihood ratio test.

Among older adults, the odds of reporting that their physical health considerably limits the kinds of activities they performed were reduced by 63% compared with the younger group (OR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.24–0.58). Similarly, the odds of reporting that their health frequently causes them to accomplish less than they would like were also lower in older adults (OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.25–0.60). The odds of reporting that their breathing problem stops them from doing most things or everything they would like to do were 65% lower (OR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.22–0.55) in older adults versus younger adults (Figure 1).

Complete results for each logistic regression model are available in the online supplement (Tables E2–E7). In a sensitivity analysis, adjustment for the indication for tissue collection did not change the direction, magnitude, or significance of the ORs. A sensitivity analysis was also performed that included comorbid diseases, and this did not significantly affect the results. We performed analyses that examined lung function as absolute measures rather than % predicted and analyses that modeled age as a continuous variable rather than a categorical variable, and the results were all consistent with our main findings. In analyses that included participants with missing 6MWD and DlCO data, we found similar results to our main findings except for the question related to health effects on climbing stairs, where there was no significant relationship between the response and age category when we excluded DlCO and 6MWD from the model (Table E8).

Discussion

In this study of LTRC participants with COPD and ILD, adults 65 years of age and older were less likely to report significant impairment compared with younger adults. On average, older adults had lower total SGRQ scores and higher SF-12 MCS and PCS scores, consistent with better health status. Older adults were less likely to describe their health status as fair or poor compared with younger participants, and they were less likely to report that their health significantly limits their activities. They were also less likely to indicate that their respiratory disease prohibits them from doing all or most of the things they would like to do.

Our findings were robust, with similar results across multiple questions about the impact of health on functional impairment. Moreover, our results were consistent even after accounting for objective measures of physiologic impairment and functional limitation as well as other potential confounders. Older adults had better lung function on average compared with the younger adults in this study, with higher FEV1 and FVC, including both percent predicted and absolute values. Because absolute measures of lung function such as FEV1 correlate with ventilatory capacity and exercise capacity, this is an important potential confounder in our study. However, after adjusting for these measures of pulmonary function, our findings were the same. We also found our results were the same after accounting for 6MWD, which is an objective measure of physical function that assesses the integrated responses of multiple systems to exercise.

Our study findings may be considered unexpected, insofar as many people view older individuals as more impaired compared with younger adults. Beyond chronic lung diseases, other causes of functional impairment, such as joint disease, stroke, and heart disease, are also more common in older adults, and, therefore, individuals may accumulate multiple debilitating conditions with advancing age. In spite of this, older adults tend to be optimistic regarding their health and its impact on their quality of life, as prior work has demonstrated (1–3).

There are several possible explanations why older adults reported less impairment compared with younger adults in our study. First, older adults may answer questionnaires differently. Our findings may reflect that older adults have a tendency to provide more socially desirable responses, which has been previously demonstrated among elderly research participants (22). Second, older adults may interpret questions about their health differently. For example, elderly individuals may attribute limitations in functional status to “old age,” rather than disease (23). Therefore, health survey questions that ask about limitations related to health status may not capture information about limitations that older adults have inappropriately attributed to aging. Third, it is possible that sensory differences associated with aging may have influenced our results. For instance, prior studies have suggested that perception of bronchoconstriction may be blunted in elderly individuals (24) and that normal aging alters the perception of resistive ventilatory loads, elastic loads, and the sensation of lung volume changes (25–27). There is conflicting evidence about whether elderly adults have a blunted or enhanced perception of dyspnea (28, 29). Fourth, our results may represent a cohort effect, whereby attitudes about health and quality of life are different in those born before World War II compared with those born after. Finally, our findings may be explained by changing life stressors and societal expectations over the lifespan. As a result, younger adults may perceive more limitation because of greater responsibilities related to work and family and higher expectations for functional status. For our main analyses, we arbitrarily designated older adults as those at least 65 years old, in accordance with the U.S. Census Bureau definition, but in separate analyses that examined age as a continuous variable we found no evidence of a threshold effect at age 65 years. Therefore, we cannot attribute our findings solely to retirement or the acquisition of social security benefits at age 65 years. Older adults may also experience the onset of chronic lung disease over a longer time frame, allowing for better adaptation to their illness and its limitations (30).

Study limitations include that complete data were not available for all individuals. In particular, 6MWD was missing for 22% of participants (n = 184). We restricted our main analyses to those with 6MWD data because we wanted to learn about perceptions of impairment and therefore needed to account for an objective measure of functional status to limit confounding due to other causes of physical impairment that may differ by age. We also did not focus on factors beyond age that may affect responses to health status questions, such as lung function or pulmonary diagnosis. In a prior publication, our group demonstrated that LTRC participants with ILD reported worse health status compared with those with COPD (11), which is why we included pulmonary diagnosis in our models for the results presented here. A major strength of our study is that our data come from the well-characterized multicenter LTRC cohort, with all participants undergoing protocol-driven evaluation, including formal assessment of health status, physiologic function, and overall clinical diagnosis based on clinical data, imaging results, and pathologic findings.

In summary, older adults with chronic lung disease report less impairment than younger adults, suggesting they may perceive less limitation. This is an important finding that must be considered when interpreting the results of clinical trials that assess health status as an endpoint. Further research is necessary to determine how this might affect the minimal important difference in health status scores among older adults, as instruments such as SGRQ and SF-12 may be less responsive to change in elder patients.

Figure 1.

Relative odds of response indicating significant impairment in older adults compared with younger adults (age < 65 yr) with chronic lung disease. *Odds ratio (shown as point estimate with 95% confidence intervals) comparing older adults to younger adults for health status questionnaire response after adjusting for physiologic impairment (FEV1 % predicted, FVC % predicted, diffusing capacity % predicted), sex, body mass index, race, pulmonary diagnosis, and an objective measure of functional capacity (6-min-walk distance).

Footnotes

Supported by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1KL2RR025006-01, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Data were provided by the Lung Tissue Research Consortium, which is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Author Contributions: C.E.B., M.K.H., and R.A.W. were involved in the conception, hypotheses delineation, and design of the study. B.T., A.H.L., F.J.M., M.I.S., F.C.S., and G.J.C. were involved acquisition of the data or the analysis and interpretation of such information. C.E.B. and R.A.W. were involved in writing the article or substantial involvement in its revision before submission.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Kutner NG, Ory MG, Baker DI, Schechtman KB, Hornbrook MC, Mulrow CD. Measuring the quality of life of the elderly in health promotion intervention clinical trials. Public Health Rep. 1992;107:530–539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cockerham WC, Sharp K, Wilcox JA. Aging and perceived health status. J Gerontol. 1983;38:349–355. doi: 10.1093/geronj/38.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ory MG. Considerations in the development of age-sensitive indicators for assessing health promotion. Health Promot. 1988;3:139–150. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry CE, Han MK, Limper AH, Martinez FJ, Schwarz MI, Sciurba FC, Wise RA. Older adults with chronic lung disease perceive less impairment [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:A1491. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM. The St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Respir Med. 1991;85:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1321–1327. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engstrom CP, Persson LO, Larsson S, Sullivan M. Health-related quality of life in COPD: why both disease-specific and generic measures should be used. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:69–76. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00044901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang JA, Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Raghu G. Assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with interstitial lung disease. Chest. 1999;116:1175–1182. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.5.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swigris JJ, Brown KK, Behr J, du Bois RM, King TE, Raghu G, Wamboldt FS. The SF-36 and SGRQ: validity and first look at minimum important differences in IPF. Respir Med. 2010;104:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berry CE, Drummond MB, Han MK, Li D, Fuller C, Limper AH, Martinez FJ, Schwarz MI, Sciurba FC, Wise RA. Relationship between lung function impairment and health-related quality of life in COPD and interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2012;142:704–711. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stahl E, Lindberg A, Jansson SA, Ronmark E, Svensson K, Andersson F, Lofdahl CG, Lundback B. Health-related quality of life is related to COPD disease severity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:56. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajiro T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, Ikeda A, Koyama H, Izumi T. Comparison of discriminative properties among disease-specific questionnaires for measuring health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:785–790. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.3.9703055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajiro T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, Ikeda A, Oga T. Stages of disease severity and factors that affect the health status of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2000;94:841–846. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han MK, Swigris J, Liu L, Bartholmai B, Murray S, Giardino N, Thompson B, Frederick M, Li D, Schwarz M, et al. Gender influences health-related quality of life in IPF. Respir Med. 2010;104:724–730. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voll-Aanerud M, Eagan TM, Wentzel-Larsen T, Gulsvik A, Bakke PS. Respiratory symptoms, COPD severity, and health related quality of life in a general population sample. Respir Med. 2008;102:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin A, Rodriguez-Gonzalez Moro JM, Izquierdo JL, Gobartt E, de Lucas P. Health-related quality of life in outpatients with COPD in daily practice: the VICE Spanish Study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:683–692. doi: 10.2147/copd.s4791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carrasco Garrido P, de Miguel Diez J, Rejas Gutierrez J, Centeno AM, Gobartt Vazquez E, Gil de Miguel A, Garcia Carballo M, Jimenez Garcia R. Negative impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on the health-related quality of life of patients. Results of the EPIDEPOC study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:31. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macintyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G, Johnson DC, van der Grinten CP, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Enright P, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:720–735. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soubelet A, Salthouse TA. Influence of social desirability on age differences in self-reports of mood and personality. J Pers. 2011;79:741–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williamson JD, Fried LP. Characterization of older adults who attribute functional decrements to “old age.”. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1429–1434. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb04066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connolly MJ, Crowley JJ, Charan NB, Nielson CP, Vestal RE. Reduced subjective awareness of bronchoconstriction provoked by methacholine in elderly asthmatic and normal subjects as measured on a simple awareness scale. Thorax. 1992;47:410–413. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.6.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tack M, Altose MD, Cherniack NS. Effects of aging on sensation of respiratory force and displacement. J Appl Physiol. 1983;55:1433–1440. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.5.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tack M, Altose MD, Cherniack NS. Effect of aging on respiratory sensations produced by elastic loads. J Appl Physiol. 1981;50:844–850. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.50.4.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tack M, Altose MD, Cherniack NS. Effect of aging on the perception of resistive ventilatory loads. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;126:463–467. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.126.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akiyama Y, Nishimura M, Kobayashi S, Yamamoto M, Miyamoto K, Kawakami Y. Effects of aging on respiratory load compensation and dyspnea sensation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1586–1591. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.6_Pt_1.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Battaglia S, Sandrini MC, Catalano F, Arcoleo G, Giardini G, Vergani C, Bellia V. Effects of aging on sensation of dyspnea and health-related quality of life in elderly asthmatics. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17:287–292. doi: 10.1007/BF03324612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hickey A, Barker M, McGee H, O’Boyle C. Measuring health-related quality of life in older patient populations: a review of current approaches. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:971–993. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523100-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]