Abstract

Rationale: All bronchoscopists will encounter, at some point, central airway obstruction (CAO) and will face the problem of documenting its severity. Axial imaging is suggested as the gold standard for assessing CAO, but anecdotal evidence indicates that many bronchoscopists use visual estimation. The prevalence and reliability of this method have not been extensively studied.

Objectives: This study aimed to determine bronchoscopists’ opinions about assessing CAO and to assess the variability of visual estimation.

Methods: All 438 members of the American Association of Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology were invited to participate in an online questionnaire. In addition to reporting opinions and practice in measuring CAO, participants estimated degree of obstruction for 10 bronchoscopic photos of abnormal central airway lesions using a sliding scale from 0 to 100%.

Measurements and Main Results: Responses were obtained from 118 individuals with varied interventional bronchoscopy experience. Most participants reported using visual estimation of CAO (91%) and largely by numeric estimates (87%). A total of 55 participants volunteered additional methods they employed, and their comments reflected discontent with the dependability of those. When shown the same 10 bronchoscopic photos, estimates varied considerably, with very large ranges of responses for all images. Most (86%) agreed that measurement of airway narrowing should be standardized.

Conclusions: Although limited by sample size and static photos of abnormal airways, this study supports the tenet that most bronchoscopists use a subjective and variable method of estimating CAO, which is anecdotally pervasive in the absence of a clinically practical alternative.

Keywords: tracheal stenosis, lung transplant, tracheal neoplasm, Wegener’s granulomatosis, bronchial stenosis

Central airway obstruction (CAO) is a common clinical entity, the exact prevalence of which is unknown, but is encountered by most bronchoscopists at some point in their practice. In documenting the obstruction, clinicians must not only describe the lesion, but also quantify the degree of obstruction. Whether communicating lesion severity to another physician, or monitoring progression or therapeutic response, a reliable measure of degree of CAO is needed. Despite the routine nature of this problem, no widely accepted standard method exists for documenting, communicating, and comparing CAO lesions.

Advances in the field of interventional pulmonology permit a variety of therapeutic and palliative procedures (1). Consequently, precise measurements of change over time are needed to demonstrate change, or lack thereof, with interventions. Spirometry has historically been a measure of airway obstruction, and likely will improve after therapeutic intervention of severe CAO (2). However, spirometry offers no insight for procedural planning, and may be confounded by coexistent peripheral airways disease. Computed tomography (CT) with three-dimensional reconstruction offers virtual bronchoscopic views, but limitations of axial imaging include radiation, scheduling at a site remote from the site of procedure, and variation based on phase of respiration (3).

Methods that quantify CAO without ionizing radiation have relied primarily upon bronchoscopic image processing (4, 5). Majid and colleagues (6) demonstrated favorable inter- and intraobserver reliability using bronchoscopy to measure anterior–posterior airway luminal dimensions in patients with dynamic airway collapse. Murgu and Colt (7) have been proponents of morphometric bronchoscopy, which uses image software processing techniques that enable analysis of still digital images to measure airway lumen caliber. Studies in normal patients and patients with tracheobronchomalacia and benign strictures have demonstrated that morphometric bronchoscopy reliably measured airway caliber, had high intra- and interobserver agreement, and correlated well with measurements performed by CT (4, 8, 9). However, this method has disadvantages in terms of providing real-time measurements, and has not been widely adopted (10).

Due to difficulties associated with the methods described thus far here, anecdotal evidence suggests that bronchoscopists customarily use visual estimation of airway obstruction for documentation and communication. Qualitative classifications of fixed CAO severity using visual estimation, however, are not reliable in fixed, benign airway strictures, as shown by Murgu and Colt (10).

The precision and accuracy of visual estimation technique has not been well studied in malignant airway obstruction and in CAO of combined etiology. The extent to which various measurement approaches are used, alone or in combination, to describe CAO in clinical practice is also not known. Although there is an imperative to standardize the tools for measuring CAO, it would be impossible to develop a satisfactory tool until we understand the current practice as well as its limitations and advantages. We seek to add to the sparse literature in this field by assessing what method(s) bronchoscopists use in daily practice, and how reliable, reproducible, and consistent these measurements are by providing sample bronchoscopic pictures for visual estimation of degree of obstruction.

Methods

An 18-item questionnaire was developed for online distribution to members of the American Association of Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology (AABIP). Members of AABIP join voluntarily in accordance with their interest in and experience with advanced diagnostic and therapeutic bronchoscopy, and, thus, are likely to have more experience with CAO than the average bronchoscopist. Invitations were electronically mailed by the organization. First, respondents’ opinions about estimation of CAO and practice characteristics were asked. Then, 10 photographs were presented in fixed sequence to all respondents. The photographs were images obtained by flexible videobronchoscopy that best captured the nature of the lesion, as judged by the bronchoscopist (BF-P180 or BF-1T180; Olympus USA, Center Valley, PA). These included malignant and nonmalignant fixed lesions of the trachea and proximal airways. Respondents were asked to visually estimate degree of airway obstruction using a slide tool ranging in 1% increments from 0 to 100% obstruction. Reponses were anonymous, but information about training and procedural experience was requested. The authors characterized each lesion based on regularity, underlying process, central airway location, malignancy, and qualitative degree of obstruction, but these descriptors were not shared with the respondents. A stenosis index (SI) was calculated for each image, as described by Murgu and Colt (7). Cross-sectional area (CSA) of the airway was calculated using Fiji (http://fiji.sc/Fiji), which is an imaging analysis software similar to ImageJ software provided by the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Using the region of polygon selection and measure tools, the area of the airway at the narrowing was calculated in pixels. Similarly, the area of the normal airway proximal to the narrowing was measured in pixels. An SI is then calculated using the formula,

The SI was not provided to the respondents.

A total of three e-mails was sent between December 2013 and January 2014 from the AABIP to members. Each e-mail contained an identical questionnaire link and background information about the purpose of the study, as well as the contact information for the investigators.

The questionnaire was conducted via a University of Minnesota license with Qualtrics Survey Software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Bronchoscopic photos were taken as part of clinical care, and were deidentified by one of the investigators (H.J.M.) before inclusion in the questionnaire. This study was exempt from review by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analysis

Using a P value of 0.05, mean estimates were compared by independent t test for groups by lesion type, as well as bronchoscopists’ experience level. Respondents were classified as less experienced (fewer than 50 airway interventions) and more experienced (50 or more airway interventions), and responses for each visual estimate were compared. For the one lesion (image 8) associated with lung transplant, respondents were also grouped based on whether they reported caring for patients who had undergone transplant.

Results

Respondents

A total of 438 members were invited to participate in the questionnaire, and 123 responses were received. The majority of respondents were pulmonologists, and most indicated that they had performed at least 50 central airway interventions, such as endobronchial stenting, dilation, and tissue ablation (see Table 1). Nearly all respondents reported treating patients with lung cancer and inflammatory endobronchial disease, whereas about three-fourths of respondents reported treating patients with a tracheostomy. Only one-third reported treating patients who had undergone lung transplant. About one-half (48%) of respondents reported having performed between 50 and 500 airway interventions, such as balloon dilation, stenting, or tissue-ablative techniques. Another 18% reported performing over 500 airway interventions in their careers. Only seven individuals (6%) had performed less than five airway interventions.

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics (n = 118)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Primary specialty = pulmonology | 113 (97) |

| Treat lung cancer | 115 (97) |

| Treat patients after lung transplant | 40 (34) |

| Treat patients after tracheostomy | 88 (75) |

| Treat inflammatory endobronchial disease | 101 (86) |

| Performed >50 central airway interventions | 77 (65) |

Duplicates and Blanks

Three responses were completely blank, and were excluded from analysis. No individual estimates were removed, as assessing variability was one objective of the study. Duplicate responses were ascertained by comparing Internet protocol (IP) addresses. When these occurred, responses to demographic questions were compared for similarity. Several pairs of duplicate IP addresses occurred with different demographic and visual estimate responses. This was considered to represent multiple responses by individuals sharing an Internet connection. One of the repeated IP addresses appeared to be from an individual respondent associated with triplicate responses on all questions, so only one of the identical response sets was included. Missing values (i.e., unanswered questions) were rare, at less than 5% for each question.

Opinions and Practices in Measuring CAO

Most bronchoscopists (91%) reported using visual estimation of the degree of obstruction, and most of those (86%) use numeric description (see Table 2). A majority of respondents (86%) did agree with the statement, “Standardizing measurement of airway narrowing is important.” About one-half of the respondents employ additional methods of measuring CAO.

Table 2.

Measuring central airway obstruction opinions and practices

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Use visual estimation to grade degree of CAO | 107 (91) |

| Use numeric description of degree of CAO | 102 (87) |

| Standardizing CAO measurement is important | |

| Strongly agree | 54 (46) |

| Somewhat agree | 47 (40) |

| Use adjunctive tools to measure CAO | 55 (47) |

Definition of abbreviation: CAO = central airway obstruction.

Other Methods of Grading CAO

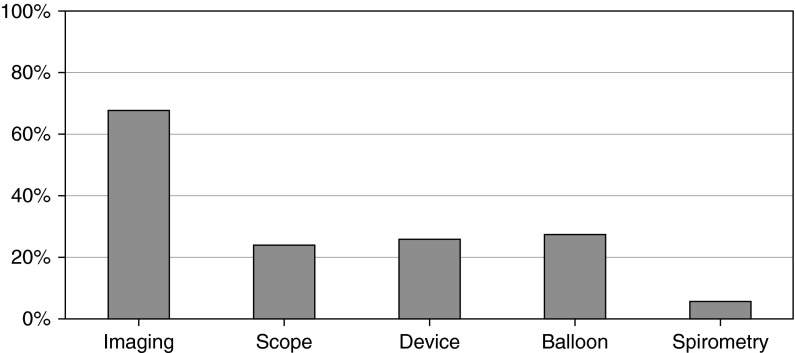

A total of 55 respondents volunteered other means of assessing CAO (see Figure 1). Most commonly, imaging modalities were used, primarily CT, including three-dimensional reconstruction. Other modalities were: airway sizing device or other device with known dimension; size of the lesion relative to the bronchoscope diameter; and use of a balloon, such as a controlled radial expansion balloon. Three respondents reported using spirometry to assist in grading CAO. Opinions about the utility of available tools were also expressed in the free text responses:

Figure 1.

Additional methods of measurement. A total of 55 respondents listed additional methods that they use to measure central airway obstruction (CAO; percentage of those shown next to type of additional method used). “Imaging” responses include computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and bronchography. “Scope” responses compare the known diameter of a rigid or flexible bronchoscope to the lesion. “Device” responses included stent-sizing devices or biopsy forceps. “Balloon” responses mentioned using the size or pressure of a balloon, such as a controlled radial expansion balloon. “Spirometry” responses reported pulmonary function test or spirometry.

“I obtain an initial idea from the CT scan, but this usually is an underestimation…”

“…scope or other instruments (measurement device but that didn't work well enough)…”

“We of course use a visual estimate…but it is quite inadequate by itself.”

Estimation of Degree of Obstruction

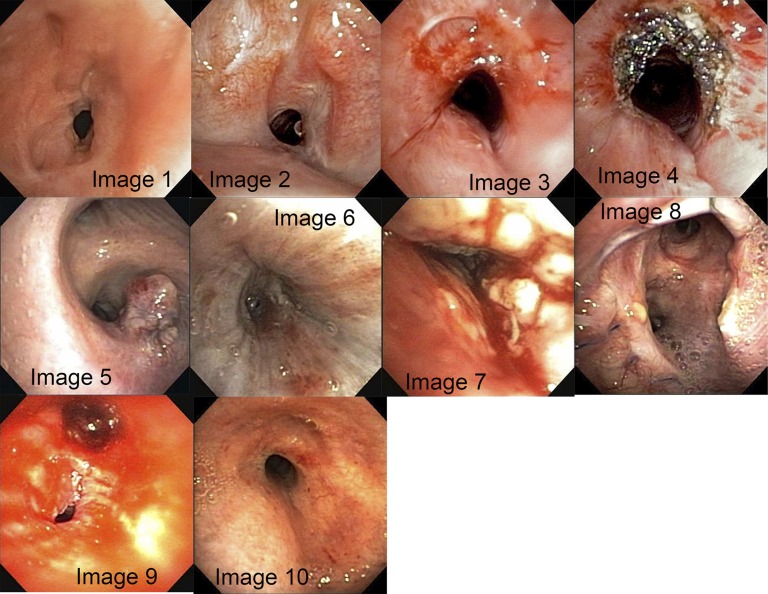

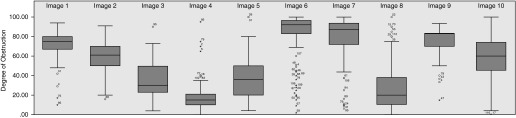

Ten bronchoscopic images were presented for respondents to visually estimate the degree of obstruction (Figure 2), and the distributions of individual estimates of degree of obstruction along with the calculated SI are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Images included in questionnaire for visual estimation of degree of obstruction, mean estimates (±SD), and stenosis index (SI). Image 1: mean = 72.1% (±14.0); SI = 95. Image 2: mean = 60.4% (±15.0); SI = 85. Image 3: mean = 34.4% (±15.6); SI = 62. Image 4: mean = 18.8% (±14.0); SI = 54. Image 5: mean = 36.8% (±19.3); SI = 67. Image 6: mean = 83.2% (±23.5); SI = 100. Image 7: mean = 82.9% (±16.9); SI = 94. Image 8: mean = 27.7% (±16.9); SI = 50. Image 9: mean = 86.3% (±7.6); SI = 94. Image 10: mean = 58.4% (±21.0); SI = 86.

Figure 3.

Distribution of estimates by image number. All individual estimates for each image are included in conventional box plots. The box designates the middle 50th percentile (25th–75th percentile), with a solid black line representing the median estimate. The whiskers denote 1.5 × interquartile range (IQR). Outliers are labeled with respondent identification number. Circle indicates an outlier, whereas extreme outliers are those outside of 3 × IQR, and are indicated with an asterisk.

Because we sought to estimate variability of response, no estimates were removed. Instead, outliers were identified in this nonparametric distribution using the lower half of the first quartile and upper half of the fourth quartile as the lower and upper limits, respectively. Image 6 had the highest number of outliers with 17 (15%) responses. Images 4, 7, and 8 each had seven outlier responses (6%). Using SD as the measure of estimate variability, image 9 had the least variability in response.

Only one image (image 8, a lung transplant anastomosis) demonstrated significantly different group means for visual estimation when more experienced and less experienced bronchoscopists’ estimates were compared (P = 0.001). However, when estimates for this same image were compared between respondents who did and did not see transplant patients, there was no significant difference.

About one-half of all individual estimates (540/1,161) of degree of obstruction were in factors of 10, whereas another 17% (199) were in factors of five. In all, 64% were “round” numbers or divisible by 5 (e.g., 65% obstruction, 10% obstruction). A total of 24 respondents only used such round numbers, whereas most included some less-round numbers. This pattern was independent of procedural experience; each experience group’s proportion of round estimates was 62–64%.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that bronchoscopists predominantly use numeric visual estimation to determine the degree of CAO. Furthermore, they agree that a standard measurement method is important. In this sample of subspecialists, the visual estimation of degree of obstruction on the same lesion is highly variable, and does not seem to differ significantly with experience. These findings support those previously reported by Murgu and Colt (10). In this study, evaluating the ability of 42 bronchoscopists to grade the degree of airway obstruction from benign airway strictures using still bronchoscopic images, only 47% of the strictures were correctly classified by the participants. Using a classification scheme of mild (<50%), moderate (50–70%), and severe (>70%) obstruction, 9% of the incorrect responses overclassified the obstruction and 91% of the incorrect responses underclassified the obstruction. In contrast, a study by Majid and colleagues (6), assessing the ability of 23 pulmonologists to grade the degree of central airway collapse from tracheobronchomalacia using bronchoscopic still images, found interobserver agreement correlation coefficients ranging from 0.68 to 0.92, and intraobserver agreement correlation coefficients ranging from 0.80 to 0.96, depending on the site of dynamic collapse. In that study, participants were asked to provide the percentage of airway narrowing. In our study, the lesion type did not predict the precision of visual estimation. Regardless of experience, most bronchoscopists use “round” estimates for visually assessing CAO, which likely reflects the imprecision of this technique. Assessing the free-text responses as a part of the questionnaire, most bronchoscopists are clearly unsatisfied with currently available tools.

Few investigators in the past have addressed standardized approaches to characterizing fixed CAO lesions. Freitag and colleagues (11) classified CAO lesions qualitatively according to lesion type, but did not address degree of obstruction. Williamson and colleagues (3) offered a concise review of the currently available techniques and limitations inherent to quantifying airway dimensions. Technologic advances permit high-resolution axial imaging for detailed and accurate noninvasive airway characterization. Studies of virtual bronchoscopy have found fairly good correlation between the degree of airway narrowing noted on imaging and bronchoscopic findings (12, 13). Unfortunately, methods relying upon axial imaging are expensive, remote from the point of bronchoscopy, impractical to perform frequently, may be hindered by secretions, and scanning may be difficult or unreasonable in critically ill patients. Many also require ionizing radiation.

Quantification of bronchoscopic images, known as morphometric bronchoscopy, is attractive, although problematic, given radial, or barrel, distortion from the wide-angle “fish-eye” lens of the bronchoscope. Radial distortion increases as the area of interest is further away from the center of the field of view and as the bronchoscope is further away from the area of interest. Investigators have attempted to correct for this using mathematical polynomial distortion correction functions (14) or coordinate transformation (5, 15). These computational approaches to image analysis have not gained widespread use, presumably due to complexity. Some researchers have used a calibration marker of known size in addition to computer software for quantitative morphometric bronchoscopy (16). However, most of the studies using this technique have been ex vivo and animal studies (14). Other investigators describe a quantitative bronchoscopy methodology combining a lens magnification correction with a “color histogram mode technique” of image analysis using the ImageJ software (9, 17). This technique has primarily been used to measure airway sizes in pediatric patients. As an alternative to quantitative approaches, semiquantitative techniques without calibration markers have been used by some researchers (7, 8). Semiquantitative methods rely upon software, such as ImageJ, to measure the CSA of the stenosis and normal airway distal to the stenosis in pixels. A ratio to estimate the degree of obstruction may then be calculated from the measured CSAs. Of note, none of the participants in our study reported use of quantitative or semiquantitative techniques to measure the degree of airway stenosis.

Some newer technologies have the potential to quantify airway dimensions. Endobronchial ultrasound, using a radial probe, has been used to measure airway diameter before stent placement in patients with malignant and benign stenoses (18). Optical coherence tomography imaging during bronchoscopy has been demonstrated to correlate relatively well with CT measurements in a few studies (19, 20).

An ideal method to estimate CAO should be easy to use, readily available during bronchoscopy, and demonstrate inter- and intraobserver reproducibility. It should be safe and accurate, irrespective of the etiology, size, location, or degree of obstruction, without adding significantly to the cost or duration of the procedure. Image processing with freely available software is promising (7), but is not being used by any of the participants in this study, suggesting that it is not optimally user friendly. Due to limitations of these aforementioned methods, clinicians ultimately rely upon visual estimation to measure CAO. Although inexpensive, readily available, and convenient, visual estimation has several disadvantages. As demonstrated in our study, there is considerable variation in the estimation of the degree of CAO among bronchoscopists. This can significantly affect patient care, as underestimation of degree of airway obstruction can lead to an unnecessary search for alternative causes of dyspnea, thereby increasing costs and delaying appropriate therapy. Delay in appropriate therapy has the potential for respiratory failure, and seriously compromises patient safety. On the other hand, overestimation of CAO may prompt referral for unnecessary invasive interventions instead of seeking more likely alternative explanations. However, to rigorously validate and compare the effectiveness of interventional bronchoscopy procedures, a repeatable and quantitative anatomic measure is invaluable. Our study thus reinforces the necessity and urgency of developing a standardized tool to measure CAO.

Even a perfect measurement technique cannot replace clinical decision making in a patient with CAO. An individual patient’s symptoms, extent of physiologic dysfunction, and comorbid limitations are important to consider when assessing the need for treatment or response to treatment. Although a healthy patient may tolerate profound obstruction of the central airway, others may develop symptoms before substantial narrowing occurs (21). The degree of anatomic narrowing is an important, albeit incomplete, assessment of CAO severity.

Some of the drawbacks of our study include a small sample size, using a highly selected group of clinicians who are members of AABIP, and using still photos taken with a bronchoscope. Not only do most bronchoscopists use bronchoscopic video, but also the wide-angle lens adds significant image distortion (22), which can vary based on distance of the CAO from the lens (23). The photos included were not intentionally taken from a specified distance proximal to the lesions. Because most of the participants were pulmonologists, our results may not apply to bronchoscopists in other specialties, such as thoracic surgery, ear, nose, and throat, or anesthesiology. Ours, nevertheless, is the first and only study to report the methods that bronchoscopists use, and one of the few to highlight imprecision of common methods for measuring an important clinical problem, such as CAO.

Although all bronchoscopists face abnormal lesions in central tracheobronchial tree, a gold-standard technique for quantifying the degree of abnormality, in our opinion, is lacking. Were bronchoscopists able to demonstrate precise estimates, one might have faith in the limited utility of visual estimation of degree of CAO. Tradition and lack of a better alternative drive the method that many of us use, which, as this study shows, is imprecise and variable at best. We hope that, based on the results of our study, there will be awareness of the imprecision of this pervasive method, as well as continued impetus for research in the field to develop a standardized tool to consistently and reproducibly measure CAO.

Conclusions

Although we are not the first investigators to observe that quantifying CAO is suboptimal, this is the first published report of bronchoscopists’ opinions and practices quantifying CAO. This study serves to highlight the pervasive use of an imprecise method and to encourage further research into a better method or use of previously described methods that are more accurate. That method should ideally be convenient, rapid, repeatable, precise, and safe.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Victor Barocas, Ph.D., for his inquisitive suggestion that a study such as this would contribute to the body of knowledge in the field.

Footnotes

Supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health award UL1TR000114.

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors, and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions: A.B. and H.J.M. made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, participated in the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work, contributed to drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved; E.M.H. and J.E.C. made substantial contributions to the design of the work, participated in the interpretation of data for the work, contributed to revising the work critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved; M.A.J. participated in the interpretation of data for the work, contributed to revising the work critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Wahidi MM, Herth FJ, Ernst A. State of the art: interventional pulmonology. Chest. 2007;131:261–274. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-0975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vergnon JM, Costes F, Bayon MC, Emonot A. Efficacy of tracheal and bronchial stent placement on respiratory functional tests. Chest. 1995;107:741–746. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.3.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson JP, James AL, Phillips MJ, Sampson DD, Hillman DR, Eastwood PR. Quantifying tracheobronchial tree dimensions: methods, limitations and emerging techniques. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:42–55. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00020408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forkert L, Watanabe H, Sutherland K, Vincent S, Fisher JT. Quantitative videobronchoscopy: a new technique to assess airway caliber. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1794–1803. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.6.8970373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dörffel WV, Fietze I, Hentschel D, Liebetruth J, Rückert Y, Rogalla P, Wernecke KD, Baumann G, Witt C. A new bronchoscopic method to measure airway size. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:783–788. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d09.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majid A, Gaurav K, Sanchez JM, Berger RL, Folch E, Fernandez-Bussy S, Ernst A, Gangadharan SP. Evaluation of tracheobronchomalacia by dynamic flexible bronchoscopy: a pilot study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:951–955. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201312-435BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murgu S, Colt HG. Morphometric bronchoscopy in adults with central airway obstruction: case illustrations and review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1318–1324. doi: 10.1002/lary.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rozycki HJ, Van Houten ML, Elliott GR. Quantitative assessment of intrathoracic airway collapse in infants and children with tracheobronchomalacia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1996;21:241–245. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199604)21:4<241::AID-PPUL7>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masters IB, Eastburn MM, Wootton R, Ware RS, Francis PW, Zimmerman PV, Chang AB. A new method for objective identification and measurement of airway lumen in paediatric flexible videobronchoscopy. Thorax. 2005;60:652–658. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.034421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murgu S, Colt H. Subjective assessment using still bronchoscopic images misclassifies airway narrowing in laryngotracheal stenosis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;16:655–660. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freitag L, Ernst A, Unger M, Kovitz K, Marquette CH. A proposed classification system of central airway stenosis. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:7–12. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00132804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mark Z, Bajzik G, Nagy A, Bogner P, Repa I, Strausz J. Comparison of virtual and fiberoptic bronchoscopy in the management of airway stenosis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2008;14:313–319. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shitrit D, Valdsislav P, Grubstein A, Bendayan D, Cohen M, Kramer MR. Accuracy of virtual bronchoscopy for grading tracheobronchial stenosis: correlation with pulmonary function test and fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Chest. 2005;128:3545–3550. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McFawn PK, Forkert L, Fisher JT. A new method to perform quantitative measurement of bronchoscopic images. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:817–826. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00077801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helferty JP, Zhang C, McLennan G, Higgins WE. Videoendoscopic distortion correction and its application to virtual guidance of endoscopy. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2001;20:605–617. doi: 10.1109/42.932745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czaja P, Soja J, Grzanka P, Cmiel A, Szczeklik A, Sładek K. Assessment of airway caliber in quantitative videobronchoscopy. Respiration. 2007;74:432–438. doi: 10.1159/000097993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masters IB, Ware RS, Zimmerman PV, Lovell B, Wootton R, Francis PV, Chang AB. Airway sizes and proportions in children quantified by a video-bronchoscopic technique. BMC Pulm Med. 2006;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nobuyama S, Kurimoto N, Matsuoka S, Inoue T, Shirakawa T, Mineshita M, Miyazawa T. Airway measurements in tracheobronchial stenosis using endobronchial ultrasonography during stenting. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2011;18:128–132. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0b013e31821bf1d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williamson JP, Armstrong JJ, McLaughlin RA, Noble PB, West AR, Becker S, Curatolo A, Noffsinger WJ, Mitchell HW, Phillips MJ, et al. Measuring airway dimensions during bronchoscopy using anatomical optical coherence tomography. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:34–41. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00041809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coxson HO, Quiney B, Sin DD, Xing L, McWilliams AM, Mayo JR, Lam S. Airway wall thickness assessed using computed tomography and optical coherence tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1201–1206. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1776OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Becker HD, Mehta AC. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:1278–1297. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1181SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vakil N. Measurement of lesions by endoscopy: an overview. Endoscopy. 1995;27:694–697. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masters IB, Eastburn MM, Francis PW, Wootton R, Zimmerman PV, Ware RS, Chang AB. Quantification of the magnification and distortion effects of a pediatric flexible video-bronchoscope. Respir Res. 2005;6:16. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]