Abstract

AIM: To evaluate when Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication therapy (ET) should be started in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding (PUB).

METHODS: Clinical data concerning adults hospitalized with PUB were retrospectively collected and analyzed. Age, sex, type and stage of peptic ulcer, whether endoscopic therapy was performed or not, methods of H. pylori detection, duration of hospitalization, and specialty of the attending physician were investigated. Factors influencing the confirmation of H. pylori infection prior to discharge were determined using multiple logistic regression analysis. The H. pylori eradication rates of patients who received ET during hospitalization and those who commenced ET as outpatients were compared.

RESULTS: A total of 232 patients with PUB were evaluated for H. pylori infection by histology and/or rapid urease testing. Of these patients, 53.7% (127/232) had confirmed results of H. pylori infection prior to discharge. In multivariate analysis, duration of hospitalization and ulcer stage were factors independently influencing whether H. pylori infection was confirmed before or after discharge. Among the patients discharged before confirmation of H. pylori infection, 13.3% (14/105) were lost to follow-up. Among the patients found to be H. pylori-positive after discharge, 41.4% (12/29) did not receive ET. There was no significant difference in the H. pylori eradication rate between patients who received ET during hospitalization and those who commenced ET as outpatients [intention-to-treat: 68.8% (53/77) vs 60% (12/20), P = 0.594; per-protocol: 82.8% (53/64) vs 80% (12/15), P = 0.723].

CONCLUSION: Because many patients with PUB who were discharged before H. pylori infection status was confirmed lost an opportunity to receive ET, we should confirm H. pylori infection and start ET prior to discharge.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Peptic ulcer hemorrhage, Disease eradication, Hospitalization, Patient discharge

Core tip: This study aimed to determine the optimal time to initiate Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication in patients hospitalized with peptic ulcer bleeding. There was no significant difference in the H. pylori eradication rate between patients who received eradication therapy during hospitalization and those who commenced therapy as outpatients. However, because many patients who were discharged before H. pylori infection was confirmed lost the opportunity to begin eradication therapy, H. pylori infection should be confirmed and eradication therapy started in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding prior to discharge.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately one-fourth of patients with peptic ulcer disease visit the emergency room, and about 75% of these patients are diagnosed with peptic ulcer bleeding (PUB)[1]. Because it is well established that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication is the most effective method to prevent bleeding recurrence in patients with PUB[2-4], most international guidelines recommend H. pylori eradication in patients infected with the disease[5,6]. Therefore, it is very important to test for H. pylori infection and perform eradication therapy as necessary in emergency room patients who are found to have PUB[7]. However, guidelines indicating the optimal time to initiate H. pylori eradication in patients with PUB are rare[8-10]. The recently published Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report recommends that H. pylori eradication treatment be started at reintroduction of oral feeding in cases of bleeding peptic ulcer[11]. They provided the following justification for their recommendation: while H. pylori eradication has no effect on the early rebleeding rate in patients with PUB, delaying treatment until after discharge leads to reduced patient compliance or loss to follow-up without receiving full treatment.

Among several roles the proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) serves in eradication therapy for H. pylori infection, increase of gastric pH is the main role as antibiotics can be unstable at low pH[12,13]. In particular, clarithromycin, which is the main antibiotic used in standard triple therapy for H. pylori infection, degrades rapidly at normal gastric pH (1.0-2.0)[14]. Therefore, PPI is used to increase gastric pH to the level needed before starting eradication therapy. While it takes at least 3 to 5 d after administration of PPI to achieve and maintain a gastric pH > 4 for a substantial proportion of each 24-h period[15], the period of nil per os in patients with PUB is usually less than 3 d. Therefore, starting eradication therapy with the reintroduction of oral feeding during hospitalization may decrease the relative efficacy of eradication therapy due to sub-optimal acid suppression. Although one meta-analysis suggested that there was no influence of pre-treatment with a PPI on H. pylori eradication[16], the subjects of most studies included in the meta-analysis were non-bleeding patients with a PPI pre-treatment duration greater than 5 d. In contrast, there are few studies comparing the efficacy of eradication therapy in patients with PUB according to initiation of eradication therapy. A British study suggested as evidence for eradication therapy during hospitalization in the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report previously referenced, did not mention this topic[17]. In addition, because it takes several days to confirm histologic results and because antibiotics used in eradication therapy may cause adverse effects, some physicians prefer to start eradication therapy when the patient is more stable after discharge, as opposed to beginning ET at the time of reintroduction of oral feeding, which is a time when patients may still be acutely ill.

We set out to: (1) elucidate what portion of patients with PUB have H. pylori infection status confirmed prior to discharge and which factors influence confirmation of H. pylori infection status during hospitalization; and (2) determine whether there is a difference in the eradication rate between patients who began eradication therapy in the hospital and patients who began eradication therapy at the outpatient clinic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

All patients who met the following criteria were enrolled into the present study: first, adults aged ≥ 19 years who were admitted through the emergency room at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital between June 2003 and December 2012; second, those patients who were assigned a final diagnosis of PUB at the point of discharge; third, presence of a peptic ulcer confirmed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and H. pylori infection status evaluated by histology or rapid urease test during admission; and fourth, duration of patient’s hospitalization was ≤ 7 d. Patients with malignant ulcers or Dieulafoy’s ulcer, or with a history of H. pylori eradication were excluded. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB number: B-1403-242-106).

Hospital course and follow-up in the outpatient clinic

A retrospective review of the electronic medical record for each patient was conducted to collect data on baseline clinical characteristics. Age, sex, type and stage of peptic ulcer, whether endoscopic therapy was performed or not, methods of H. pylori detection, duration of hospitalization, and specialty of the attending physician were abstracted. Whether H. pylori infection status was confirmed or not prior to discharge was determined from the hospital discharge records. For patients who received H. pylori eradication therapy, data about the eradication regimen, smoking history, and compliance with drug treatment were also collected. The eradication rates of H. pylori in patients who started eradication therapy during hospitalization and those who started in the outpatient clinic were compared. Eradication rates of H. pylori were determined on an intent-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) basis. All enrolled patients were included in the ITT analysis. For the PP analysis, patients who were lost to follow up, or who had taken less than 85% of the prescribed drugs were excluded. A reason was sought for those patients with positive H. pylori infection but in whom eradication therapy was not prescribed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows (version 18.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). In univariate analysis, continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test and categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to identify possible covariates as significant risk factors for discharge before confirmation of H. pylori infection status. Covariates that showed a significant association in univariate analysis were subjected to multiple logistic regression analyses. Model fit was assessed using Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests. All enrolled patients were included in the ITT analysis. However, for the PP analysis, patients who were lost to follow up, had taken less than 85% of the prescribed drugs, or those who had dropped out due to severe adverse events were excluded. All results were considered to indicate statistical significance when the P value was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline clinical characteristics of the patients

The total number of patients admitted through the emergency room and discharged with a final diagnosis of PUB within 7 d or less, and in whom H. pylori infection status was evaluated, was 232. Among these patients, 53.7% (127/232) had confirmed results of H. pylori infection prior to discharge. Results were not known before discharge in the other 46.3%. Table 1 shows baseline demographics of the patients according to the time of H. pylori infection status confirmation. Patients whose H. pylori infection status was confirmed during hospitalization had both a significantly more active ulcer stage (P = 0.045) and longer duration of hospitalization than patients discharged before confirmation of H. pylori infection status (P = 0.009). However, the 2 groups were similar with respect to whether the patient received endoscopic therapy or not and specialty of the attending physician. Multivariate analysis also showed that shorter duration of hospitalization and healing stage of ulcer are independent risk factors for discharge prior to H. pylori infection status confirmation. One day more of hospitalization resulted in a 20.9% greater likelihood of H. pylori infection status confirmation before discharge (OR = 0.791, 95%CI: 0.662-0.946, P = 0.010). Compared with patients in the active ulcer stage, patients with ulcer at the healing stage were more likely to be discharged before H. pylori infection status was confirmed (OR = 2.150, 95%CI: 1.027-4.499, P = 0.042).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of patients with peptic ulcer bleeding according to the time of Helicobacter pylori infection status confirmation n (%)

| Confirmation during hospitalization (n = 127) | Confirmation after discharge (n = 105) | P value | |

| Male | 94 (74.0) | 78 (74.3) | 1.000 |

| Age mean ± SD (yr) | 68.2 ± 14.1 | 67.6 ± 15.5 | 0.751 |

| Disease | 0.667 | ||

| BGU | 100 (78.7) | 86 (81.9) | |

| DU | 10 (7.9) | 9 (8.6) | |

| BGU and DU | 17 (13.4) | 10 (9.5) | |

| Stage of ulcers | 0.045 | ||

| Active stage | 113 (89.0) | 83 (79.0) | |

| Healing stage | 14 (11.0) | 22 (21.0) | |

| Endoscopic hemostasis | 0.793 | ||

| Yes | 64 (50.4) | 51 (48.6) | |

| No | 63 (49.6) | 54 (51.4) | |

| Methods for diagnosis of H. pylori infection | 0.881 | ||

| Histology | 12 (9.4) | 12 (11.4) | |

| Rapid urease test | 11 (8.7) | 9 (8.6) | |

| Both | 104 (81.9) | 84 (80.0) | |

| Duration of hospitalization mean ± SD (d) | 4.9 ± 1.5 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 0.009 |

| Specialty of the attending physician | 0.461 | ||

| Gastroenterology | 119 (93.7) | 95 (90.5) | |

| Others | 8 (6.3) | 10 (9.5) |

BGU: Benign gastric ulcer; DU: Duodenal ulcer; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; PUB: Peptic ulcer bleeding.

Clinical course of the patients

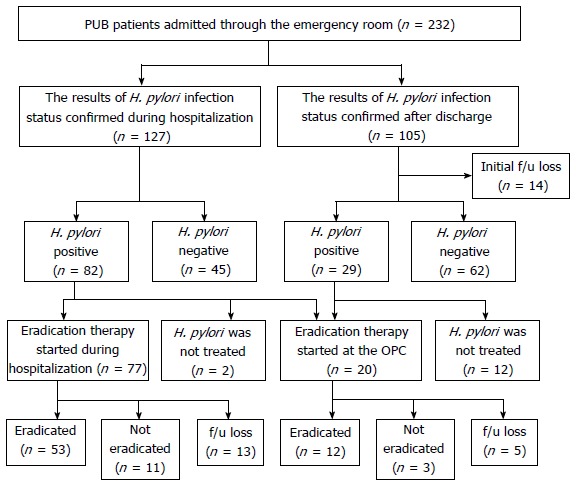

Figure 1 shows the clinical course of patients hospitalized due to PUB. Among 127 patients with confirmed H. pylori infection status prior to discharge, 64.6% (82/127) were H. pylori-positive and most (97.6%) had begun eradication therapy during their hospitalization (n = 77) or in an outpatient clinic (n = 3). Among the patients discharged prior to confirmation of H. pylori infection status results, 13.3% (14/105) were lost to follow-up. For the remaining 91 patients, the mean time period from discharge to first outpatient clinic visit was 11 d (95%CI: 10-13) and 31.9% (29/91) were found to be H. pylori-positive in the outpatient setting. Among the patients found to be H. pylori-positive in the outpatient clinic, only 58.6% (17/29) received eradication therapy. The mean time period from discharge to first day of the eradication regimen was 18 d (95%CI: 11-24 d). Eradication therapy was not performed in 2 patients whose H. pylori infection was confirmed during hospitalization and 12 patients whose H. pylori infection was confirmed after discharge. The reasons why H. pylori eradication was not performed in these 14 patients were as follows: in 6 patients, there was no description about H. pylori infection status recorded in the medical record at the first outpatient clinic visit following discharge. While positive H. pylori infection was recorded in the medical records of the remaining 8 patients, 6 patients did not receive eradication therapy and no definitive reason was recorded. The other 2 patients had planned to begin eradication therapy after treatment for their ulcers, but thereafter did not do so.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the clinical course of the patients hospitalized with peptic ulcer bleeding. f/u: Follow-up; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; OPC: Outpatient clinic; PUB: Peptic ulcer bleeding.

H. pylori eradication rates

The baseline demographics of patients who underwent H. pylori eradication treatment are summarized in Table 2. Eradication regimen and smoking history were not significantly different between the patients who received eradication therapy during hospitalization and those who commenced therapy in the outpatient clinic. Among the 97 patients who received eradication therapy for H. pylori, information about compliance was obtained in only 35.1%. However, there was little difference in compliance between the 2 groups (percentage of full compliance: 96.8% vs 100%, P = 1.0). There was no significant difference in H. pylori eradication rate between the 2 groups [ITT: 68.8% (53/77) vs 60% (12/20), P = 0.594; PP: 82.8% (53/64) vs 80% (12/15), P = 0.723] (Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline demographics of patients with peptic ulcer bleeding who underwent Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy according to the time of eradication therapy initiation n (%)

| Eradication during hospitalization (n = 77) | Eradication at the OPC(n = 20) | P value | |

| Male | 59 (76.6) | 17 (85.0) | 0.550 |

| Age mean ± SD (yr) | 66.1 ± 13.9 | 59.5 ± 15.1 | 0.063 |

| Disease | 0.833 | ||

| BGU | 57 (74.0) | 16 (80) | |

| DU | 9 (11.7) | 1 (5.0) | |

| BGU and DU | 11 (14.3) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Eradication regimen | 0.191 | ||

| 7-d triple therapy1 | 60 (77.9) | 20 (100) | |

| 10-d triple therapy | 2 (2.6) | 0 | |

| 14-d triple therapy | 10 (13.0) | 0 | |

| Others | 5 (6.5) | 0 | |

| Smoking | 0.100 | ||

| Current | 22 (28.6) | 7 (35.0) | |

| Past | 5 (6.5) | 4 (20.0) | |

| Never | 50 (64.9) | 9 (45.0) | |

| Oral iron replacement during eradication therapy | 0.113 | ||

| Yes | 30 (39.0) | 4 (20.0) | |

| No | 47 (61.0) | 16 (80.0) |

Proton-pump inhibitor standard dose bid, clarithromycin 500 mg bid, and amoxicillin 1000 mg bid. BGU: Benign gastric ulcer; DU: Duodenal ulcer; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; OPC: Outpatient clinic; PUB: Peptic ulcer bleeding.

Table 3.

Helicobacter pylori eradication rates according to the time of eradication therapy initiation in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding

| Eradication during hospitalization (n = 77) | Eradication at the OPC(n = 20) | P value | |

| ITT analysis | |||

| Eradication rate | 68.8% | 60% | 0.594 |

| 95%CI | 58.2%-79.4% | 36.5%-83.5% | |

| PP analysis | |||

| Eradication rate | 82.8% | 80% | 0.723 |

| 95%CI | 73.3%-92.3% | 57.1%-100% |

BGU: Benign gastric ulcer; DU: Duodenal ulcer; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; ITT: Intention-to-treat; OPC: Outpatient clinic; PP: Per-protocol; PUB: Peptic ulcer bleeding.

DISCUSSION

Although the recent Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report recommends that H. pylori eradication treatment be started at the reintroduction of oral feeding in cases of bleeding ulcer, One survey reported that starting eradication therapy on the first outpatient clinic visit following hospital discharge was the most common practice in South Korea[18]. In this study, we sought to evaluate whether there is a difference in the H. pylori eradication rate between patients receiving initial eradication therapy during hospitalization and patients who began therapy at the outpatient clinic following discharge. The result was negative. However, if the clinician plans to confirm H. pylori infection status at the outpatient clinic a considerable fraction of the patients will likely fail to attend a follow-up appointment, and the proportion of patients who will not receive eradication therapy will be rather high. That is, 46.9% of patients in whom the final result of H. pylori test was confirmed positive only after discharge will lose the opportunity to begin eradicating the organism. This means a substantial proportion of patients would be exposed to the risk of recurrent ulcer bleeding. Therefore, some authors have even suggested that empirical treatment of H. pylori infection immediately after re-feeding is the most cost-effective strategy, as it prevents recurrent hemorrhage in patients with PUB[19,20]. However, the cost-effectiveness of an empirical eradication therapy can vary by regional prevalence of H. pylori in PUB. Therefore, confirming results of H. pylori test and initiating eradication therapy in H. pylori-positive patients prior to discharge would appear to be a more appropriate strategy than to apply empirical eradication therapy to all patients with PUB.

To initiate eradication therapy during hospitalization in H. pylori-positive patients with PUB, it is essential to confirm H. pylori infection status prior to discharge. In this study, factors independently influencing whether H. pylori infection status is confirmed before or after discharge were duration of hospitalization and ulcer stage. Positive results of a rapid urease test can usually be obtained within 24 h by a visual check of the color change[21]. However, because the sensitivity of the rapid urease test in bleeding ulcer cases is relatively low[22-25], we could not rule out the possibility of false negative results. Therefore, although confirmation of the presence of H. pylori in the gastric tissue requires a longer time frame due to tissue preparation and examination of slides by pathologists, histologic results should be confirmed in all patients with PUB[26]. Whereas, in the case of peptic ulcer biopsy tissues submitted to the pathologist for evaluation, the slide review and final pathologic diagnosis is usually delayed because more critical cases requiring rapid decision-making (such as malignancy) take precedence. Therefore, the time discrepancy that exists between the availability of rapid urease test and histology results might be the primary reason why some patients with PUB are being discharged without final confirmation of their H. pylori infection status. While it is often not cost-effective to delay discharge by one more day in order to confirm histology results, obtaining histology results 1 d earlier is a more practical solution. Although the duration of hospitalization was significantly different between patients in whom H. pylori infection was confirmed prior to and after discharge in this study, the absolute difference in the time period was less than 24 h. Therefore, reporting pathology results just 1 d earlier would significantly reduce the number of H. pylori-infected patients with PUB who lose the opportunity to begin eradication therapy. To obtain pathology reports sooner, collaboration with pathologists will be needed. Clinicians need to establish a system to inform pathologists about the need for more rapid slide reading and diagnostic reporting in patients with PUB.

This study has several limitations. First, this study is retrospective in design. We could not fully elucidate the reason for discharge prior to confirmation of H. pylori infection in each patient. Instead, from our finding that hospital duration was an independent factor influencing whether H. pylori infection was confirmed prior to or after discharge, we speculated that the time discrepancy between rapid urease test and histology was the primary reason why patients with PUB were being discharged without final confirmation of their H. pylori infection status. However, because the attending physician generally decides to check H. pylori infection in patients with PUB during hospitalization, there is a possibility of selection bias by attending physician. Second, we were not able to investigate antibiotic resistance in each patient who received eradication therapy. Third, we could not evaluate compliance for eradication therapy in some of the patients. However, strength of this study is that it reveals the actual clinical situation for management of patients with PUB.

In conclusion, there was no difference in H. pylori eradication rate by time of the initiation of eradication therapy in patients hospitalized due to PUB. However, because many patients who are discharged prior to confirmation of H. pylori infection lose an opportunity to begin eradication therapy, we suggest that H. pylori infection be confirmed and eradication therapy be started in PUB patients prior to discharge. Finally, we should never forget the fact that PUB is an absolute indication for H. pylori eradication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are indebted to Patrick Barron J, Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Medical University and Adjunct Professor, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital for his pro bono editing of this manuscript.

COMMENTS

Background

Because it is well established that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication is the most effective method to prevent recurrence in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding (PUB), most international guidelines recommend testing for H. pylori infection and eradicating this bacterium.

Research frontiers

There is a controversy as to when eradication therapy for H. pylori should be started in patients with PUB. Guidelines indicating the optimal time to initiate H. pylori eradication in patients with PUB are rare.

Innovations and breakthroughs

There was no significant difference in H. pylori eradication rate between patients who received eradication therapy during hospitalization and those who commenced therapy as outpatients. However, many patients who were discharged prior to confirming H. pylori infection lost an opportunity to have eradication therapy due to the following reasons: loss to follow-up, lack of H. pylori infection status confirmation at the first outpatient clinic visit, or forgetting to eradicate this organism at the outpatient clinic.

Applications

This study urges clinicians to confirm H. pylori infection and to start eradication therapy prior to discharge in patients hospitalized due to PUB.

Terminology

H. pylori is a bacterium found in the stomach. It is linked to the development of gastritis, peptic ulcers, and stomach cancer. To prevent recurrence in patients with PUB, it is necessary to kill this bacterium.

Peer-review

This study presents a topic of interest in clinical practice, not often considered in literature. Methods and study population are adequate, and conclusions are reasonable and of possible practical use. It is an article on an important issue, which adds to the knowledge base of a relatively controversial matter.

Footnotes

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: July 31, 2014

First decision: August 15, 2014

Article in press: October 15, 2014

P- Reviewer: Ananthakrishnan N, Guarneri F, Sugimoto M, Yula E S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Kim JJ, Kim N, Park HK, Jo HJ, Shin CM, Lee SH, Park YS, Hwang JH, Kim JW, Jeong SH, et al. [Clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed as peptic ulcer disease in the third referral center in 2007] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012;59:338–346. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2012.59.5.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, Hunt R, Rokkas T, Vakil N, Kuipers EJ. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laine L, Jensen DM. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:345–60; quiz 361. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau JY, Barkun A, Fan DM, Kuipers EJ, Yang YS, Chan FK. Challenges in the management of acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Lancet. 2013;381:2033–2043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, Sung J, Hunt RH, Martel M, Sinclair P. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101–113. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sung JJ, Chan FK, Chen M, Ching JY, Ho KY, Kachintorn U, Kim N, Lau JY, Menon J, Rani AA, et al. Asia-Pacific Working Group consensus on non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut. 2011;60:1170–1177. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.230292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenspoon J, Barkun A, Bardou M, Chiba N, Leontiadis GI, Marshall JK, Metz DC, Romagnuolo J, Sung J. Management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fock KM, Katelaris P, Sugano K, Ang TL, Hunt R, Talley NJ, Lam SK, Xiao SD, Tan HJ, Wu CY, et al. Second Asia-Pacific Consensus Guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1587–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SG, Jung HK, Lee HL, Jang JY, Lee H, Kim CG, Shin WG, Shin ES, Lee YC. [Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea, 2013 revised edition] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2013;62:3–26. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2013.62.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vakil N, Vaira D. Treatment for H. pylori infection: new challenges with antimicrobial resistance. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:383–388. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318277577b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villoria A. [Acid-related diseases: are higher doses of proton pump inhibitors more effective in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection?] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:546–547. doi: 10.1157/13127103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erah PO, Goddard AF, Barrett DA, Shaw PN, Spiller RC. The stability of amoxycillin, clarithromycin and metronidazole in gastric juice: relevance to the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:5–12. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bardou M, Martin J, Barkun A. Intravenous proton pump inhibitors: an evidence-based review of their use in gastrointestinal disorders. Drugs. 2009;69:435–448. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janssen MJ, Laheij RJ, de Boer WA, Jansen JB. Meta-analysis: the influence of pre-treatment with a proton pump inhibitor on Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:341–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAlindon ME, Taylor JS, Ryder SD. The long-term management of patients with bleeding duodenal ulcers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:505–510. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung IK, Lee DH, Kim HU, Sung IK, Kim JH. [Guidelines of treatment for bleeding peptic ulcer disease] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;54:298–308. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2009.54.5.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma VK, Sahai AV, Corder FA, Howden CW. Helicobacter pylori eradication is superior to ulcer healing with or without maintenance therapy to prevent further ulcer haemorrhage. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1939–1947. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gené E, Sanchez-Delgado J, Calvet X, Gisbert JP, Azagra R. What is the best strategy for diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori in the prevention of recurrent peptic ulcer bleeding? A cost-effectiveness analysis. Value Health. 2009;12:759–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cutler AF, Havstad S, Ma CK, Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Schubert TT. Accuracy of invasive and noninvasive tests to diagnose Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:136–141. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung IK, Hong SJ, Kim EJ, Cho JY, Kim HS, Park SH, Lee MH, Kim SJ, Shim CS. What is the best method to diagnose Helicobacter infection in bleeding peptic ulcers?: a prospective trial. Korean J Intern Med. 2001;16:147–152. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2001.16.3.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schilling D, Demel A, Adamek HE, Nüsse T, Weidmann E, Riemann JF. A negative rapid urease test is unreliable for exclusion of Helicobacter pylori infection during acute phase of ulcer bleeding. A prospective case control study. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:217–221. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gisbert JP, Abraira V. Accuracy of Helicobacter pylori diagnostic tests in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:848–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi YJ, Kim N, Lim J, Jo SY, Shin CM, Lee HS, Lee SH, Park YS, Hwang JH, Kim JW, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. Helicobacter. 2012;17:77–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mégraud F, Lehours P. Helicobacter pylori detection and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:280–322. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00033-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]