Abstract

Background

Inflammation plays an integral role in carcinogenesis and tumor progression. Inflammatory response biomarkers have shown to be promising prognostic factors for improving the predictive accuracy in various cancers. The aim of this study is to investigate the prognostic significance of pre-operative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (dNLR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR) in gastric cancer (GC).

Methods

389 patients who had undergone gastrectomy were enrolled from 2007 to 2009 in this study. NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR were calculated from peripheral blood cell count taken at pre-operation. Receiver operating curve (ROC) was used to determine the optimal cut-off levels for these biomarkers. A predictive model or nomogram was established to predict prognosis for cancer-specific survival (CSS) and disease-free survival (DFS), and the predictive accuracy of the nomogram was determined by concordance index (c-index).

Results

The median follow-up period was 24 months ranging from 3 months to 60 months. The optimal cut-off levels were 2.36 for NLR, 1.85 for dNLR, 132 for PLR and 4.95 for LMR by ROC curves analysis. Elevated NLR, dNLR and PLR were significantly associated with worse overall survival (OS), CSS and DFS, however, elevated LMR showed an adverse effect on worse OS, CSS and DFS. Multivariate analysis revealed that elevated dNLR was an independent factor for worse OS, and NLR was superior to dNLR, PLR and LMR in terms of hazard ratio (HR = 1.53, 95% CI = 1.11-2.11, P = 0.010), which was shown to be independent prognostic indicators for both CSS and DFS. Moreover, the nomogram could more accurately predict CSS (c-index: 0.89) and DFS (c-index: 0.84) in surgical GC patients.

Conclusions

Pre-operative NLR and dNLR may serve as potential prognostic biomarkers in patients with GC who underwent surgical resection. The proposed nomograms can be used for the prediction of CSS and DFS in patients with GC who have undergone gastrectomy.

Keywords: Inflammation, Gastric cancer, Prognosis, Survival, Nomogram

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common causes of cancer death worldwide [1,2], it is also the second most common cancer and the third leading cause of death among various types of cancer in China. Despite substantial progress achieved in diagnosis and treatment for GC in recent years, the overall 5-year survival rate remains unsatisfactory due to local relapses or metastasis after resection of primary GC. The survival rate will obviously be improved if the disease can be detected at an early tumor stage [3]. Because of the heterogeneity among the prognosis of GC, it is necessary to seek effective biomarkers for the early detection and prognosis prediction in patients with GC.

Recently, emerging evidence indicates that inflammation plays a critical role in the initiation and progression of numerous cancers, including GC [4,5]. About 15% of cancer-related deaths are closely associated with chronic inflammation or unresolved infection, and prolonged inflammation may lead to GC, hepatocellular carcinoma, and colorectal cancer [6]. Generally, systemic inflammatory response was the characteristic of changes in the relative levels of circulating white blood cells (WBC), largely resulting from the change of neutrophils and lymphocytes. Interestingly, cancer cells themselves can recruit and activate various leukocytes (especially neutrophils and monocytes) by T cells [7], specific chemokines [8,9] and prostaglandins [4]. The activation of platelet stimulated by proinflammatory cytokines participates in neutrophil recruitment and promotes inflammatory response [10]. The inflammatory response to tumor may contribute to tumor growth, progression and metastasis through several mechanisms, including the up-regulation of inflammatory mediators and cytokine, aberrant activation of immune regulatory cytokines, suppression of apoptosis, and DNA damage [6]. Those biomarkers in the peripheral blood that can exhibit the status of inflammation are considered as potential predictive markers for cancer prognosis.

In recent years, several indicators derived from the peripheral blood such as the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (dNLR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR) have been widely investigated as useful prognostic indicators in various kinds of cancers including GC, colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer and pancreatic cancer [11-16]. However, only one or two inflammatory biomarkers have been evaluated for the prognosis of patients with GC according to previous reports [11,17-21]. Moreover, the optimal cut-off values of the biomarkers from these studies were still inconsistent.

Therefore, further study on the prognosis values of these biomarkers in patients with GC is necessary. This study aimed to evaluate the potential prognostic biomarkers for 389 patients with GC undergoing surgical resection, and was the first study attempting to establish a prognostic nomogram with improved predictive capacity for patients with GC based on these biomarkers and the clinicopathologic parameters.

Patients and methods

Patients

Medical records of all newly diagnosed GC patients between January 2007 and January 2009 in Nanjing First Hospital (Jiangsu, China) were collected and retrospectively analyzed in the present study. The diagnosis of GC was confirmed depended on histological evidence and classified based on the seventh edition of the TNM-UICC/AJCC classification [22]. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) All patients with GC underwent a total or subtotal gastrectomy with standard lymphadenectomy. 2) No prior pre-operation anticancer treatment, such as chemotherapy, or radiotherapy. 3) Post-operation estimated life expectancy ≥ 3 months. 4) No hematology disease, infection, hyperpyrexia and gastrobrosia. 5) Informed consents were obtained from eligible patients. At last, 389 patients were enrolled in the present study. This study was approved by Medical Ethics Committee of Nanjing First Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing Medical University.

Blood sample analysis

All peripheral blood was collected in tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) pre-operation. Blood cell counts were detected by Sysmex XT-1800i Automated Hematology System (Shanghai, China), including white blood cell, neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet and monocyte counts. The concentrations of serum CEA and CA199 were measured using electrochemiluminescence by ELECSYS 2010 (Roche, Switzerland). Pre-operative neutrophil count to lymphocyte count (NLR), derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (dNLR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR) were calculated from peripheral blood cell count.

Patient follow-up

After operation, each patient was followed up regularly until January 2014 or until death (every 3 months for the first 2 years and then every 6 months up to 5th year). Physical examination, endoscopy, laboratory tests and imaging were conducted at every visit. The follow-up periods varied from 3 months to 60 months, with a median of 24 months. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from surgery to death. For drop-out patients, the date of the last follow-up was applied. Disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated from surgery to disease relapse or until the date of last follow-up. Cancer specific survival (CSS) was calculated from surgery to cancer-related death.

Statistical analysis

The optimal cut-off levels of NLR, dNLR, PLR, and LMR were determined by receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis [23,24]. The end-point based on CSS, OS or DFS was also applied to achieve the optimal cut-off points. Our results showed that the optimal cut-off levels were similar in these biomarkers (Table 1). Considering some previous studies employed CSS as the end-point to calculate the optimal cut-off point [24-26]. The optimal cut-off levels were calculated by the end-point based on CSS in the present study. Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables, and Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to compare continuous variables between groups. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Survival rates were calculated by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and the significance was evaluated by Log-rank test. The predictors for on OS, DFS and CSS determined by univariate analysis were evaluated by multivariate analysis using Cox’s proportional hazards model. Nomograms for DFS and CSS were established by R 3.0.3 software (Institute for Statistics and Mathematics, Vienna, Austria), and the predictive accuracy was evaluated by Harrell’s concordance index (c-index). All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 20.0 software (IBM, USA). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table 1.

The optimal cut-off point based on CSS, OS and DFS as end-point

| Variables | CSS | OS | DFS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | Cut-off point | AUC | Cut-off point | AUC | Cut-off point | |

| NLR | 0.703 | 2.36 | 0.692 | 2.46 | 0.680 | 2.46 |

| dNLR | 0.683 | 1.85 | 0.676 | 1.85 | 0.665 | 1.81 |

| PLR | 0.585 | 132 | 0.579 | 132 | 0.588 | 123 |

| LMR | 0.695 | 4.95 | 0.674 | 4.92 | 0.660 | 5.12 |

NLR, neutrophil count to lymphocyte count; dNLR, neutrophil count to (white cell count – neutrophil count); PLR, platelet count to lymphocyte count; CSS, cancer-specific survival; OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; AUC, area under curve.

Results

Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients

389 GC patients with 282 (72.5%) male and 107 (27.5%) female patients aged from 29 to 92 (the median age was 65 years). 15 patients had a family history of GC. The median follow-up period was 24 months. According to histological type, the number of papillary, tubular, poorly differentiated, mucinous and signetring cell carcinoma were 19 (4.9%), 81 (20.8%), 203 (52.2%), 57 (14.7%) and 29 (7.4%), respectively. Based on the seventh edition of the TNM-UICC/AJCC classification, the number of stage I-II and III-IV were 159 (40.9%) and 230 (59.1%), respectively. The number of patients with tumor grade G1-G2 and G3-G4 was 214 (55.0%) and 175 (45.0%), respectively. During the follow-up period, 302 (77.6%) patients were detected as local recurrence or distant metastasis. Among them, 270 (69.4%) patients were dead with 235 (60.2%) patients died from cancer-related disease. The median of DFS and OS was 18 months and 24 months, respectively. In addition, the median values of serum CEA, CA199, NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR were 3.16 (0.2-500) ng/ml, 12.21 (0.01-1000) U/ml, 3.19 (0.56-74.49), 2.27 (0.37-45.64), 145 (5.37-3111) and 3.97 (0.52-71.67), respectively.

The optimal thresholds for NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR

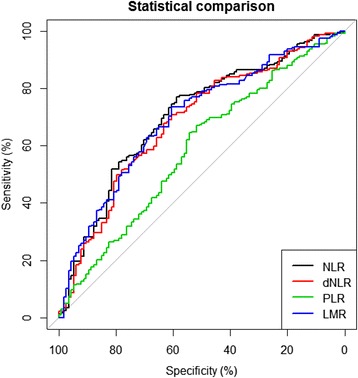

The ROC curves, using CSS as the end-point for NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR, were depicted in Figure 1. The areas under curve (AUC) for NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR were 0.703 (P = 0.000), 0.683 (P = 0.000), 0.585(P = 0.010) and 0.695 (P = 0.000), respectively. The optimal cut-off levels based on CSS were determined to be 2.36 for NLR, 1.85 for dNLR, 132 for PLR and 4.95 for LMR by ROC curves analysis. Patients were subsequently divided into two groups according to the optimal cut-off levels, with the high group ≥ the optimal cut-off levels and the low group that < the optimal cut-off levels.

Figure 1.

Optimal cut-off levels for NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR were applied with ROC curves for cancer-specific survival.

The correlation of NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR with the clinicopathologic parameters

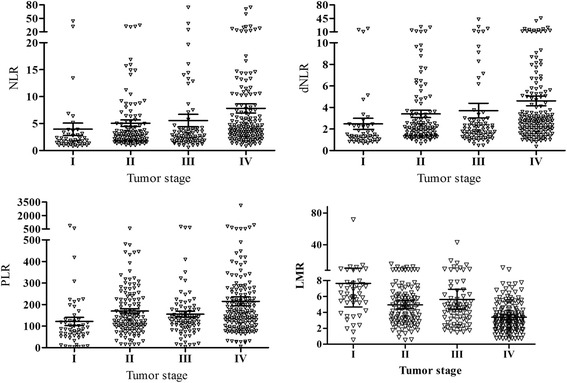

To study the correlation of NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR with clinicopathologic parameters, comparison between the high and low groups for NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR was carried out (Table 2; Figure 2). Our results revealed that NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR were significantly correlated with tumor stage, depth of invasion, lymph node, distant metastasis, CEA and CA199 (Pall < 0.05), separately. Moreover, NLR, dNLR and LMR were closely associated with the age of patients, and PLR had significant correlation with the sex of patients and histological types. Those patients with tumor stage III-IV, depth of invasion T3-T4, lymph node N1-N3 and distant metastasis M1 had a higher NLR, dNLR and PLR than those with tumor stage I-II, depth of invasion T1-T2, lymph node N0 and distant metastasis M0 (Table 3). However, no significant association was observed between tumor grade and the inflammatory biomarkers (NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR). Intriguingly, GC patients had a lower LMR in tumor stage (III-IV), depth of invasion (T3-T4), lymph node (N1-N3) and distant metastasis (M1) (Pall < 0.05, Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics according to total patients, NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR level

| Characteristics | Total patients (n = 389) | Patients grouped by NLR level (n = 389) | P * | Patients grouped by dNLR level (n = 389) | P * | Patients grouped by PLR level (n = 389) | P * | Patients grouped by LMR level (n = 389) | P * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR < 2.36 (n = 132) | NLR ≥ 2.36 (n = 257) | dNLR < 1.85 (n = 151) | dNLR ≥ 1.85 (n = 238) | PLR < 132 (n = 165) | PLR ≥ 132 (n = 224) | LMR < 4.95 (n = 241) | LMR ≥ 4.95 (n = 148) | |||||||

| Sex | Female | 107 (27.5%) | 37 (28.0%) | 70 (27.2%) | 0.868 | 41 (27.2%) | 66 (27.7%) | 0.901 | 54 (32.7%) | 53 (23.7%) | 0.048 | 59 (24.5%) | 48 (32.4%) | 0.088 |

| Male | 282 (72.5%) | 95 (72.0%) | 187 (72.8%) | 110 (72.8%) | 172 (72.3%) | 111 (67.3%) | 171 (76.3%) | 182 (75.5%) | 100 (67.6%) | |||||

| Age (years) | <65 | 185 (47.6%) | 74 (56.1%) | 111 (43.2%) | 0.016 | 83 (55.0%) | 102 (42.9%) | 0.020 | 87 (52.7%) | 98 (43.8%) | 0.080 | 98 (40.7%) | 87 (58.8%) | 0.001 |

| ≥65 | 204 (52.4%) | 58 (43.9%) | 146 (56.8%) | 68 (45.0%) | 136 (57.1%) | 78 (47.3%) | 126 (56.2%) | 143 (59.3%) | 61 (41.2%) | |||||

| Alcohol | Yes | 73 (18.8%) | 31 (23.5%) | 42 (16.3%) | 0.088 | 32 (21.2%) | 41 (17.2%) | 0.329 | 36 (21.8%) | 37 (16.5%) | 0.186 | 44 (18.3%) | 29 (19.6%) | 0.743 |

| No | 316 (81.2%) | 101 (76.5%) | 215 (83.7%) | 119 (78.8%) | 197 (82.8%) | 129 (78.2%) | 187 (83.5%) | 197 (81.7%) | 119 (80.4%) | |||||

| Tobacco | Yes | 72 (18.5%) | 29 (22.0%) | 43 (16.7%) | 0.208 | 30 (19.9%) | 42 (17.6%) | 0.583 | 37 (22.4%) | 35 (15.6%) | 0.088 | 46 (19.1%) | 26 (17.6%) | 0.708 |

| No | 317 (81.5%) | 103 (78.0%) | 214 (83.3%) | 121 (80.1%) | 196 (82.4%) | 128 (77.6%) | 189 (84.4%) | 195 (80.9%) | 122 (82.4%) | |||||

| Family history | Yes | 15 (3.9%) | 4 (3.0%) | 11 (4.3%) | 0.544 | 5 (3.3%) | 10 (4.2%) | 0.657 | 9 (5.5%) | 6 (2.7%) | 0.160 | 6 (2.5%) | 9 (6.1%) | 0.100 |

| No | 374 (96.1%) | 128 (97.0%) | 246 (95.7%) | 146 (96.7%) | 228 (95.8%) | 156 (94.5%) | 218 (97.3%) | 235 (97.5%) | 139 (93.9%) | |||||

| Histological type | papillary | 19 (4.9%) | 8 (6.1%) | 11 (4.3%) | 0.543 | 10 (6.7%) | 9 (3.8%) | 0.424 | 15 (9.1%) | 4 (1.8%) | 0.009 | 9 (3.7%) | 10 (6.8%) | 0.260 |

| tubular | 81 (20.8%) | 26 (19.7%) | 55 (21.4%) | 32 (21.1%) | 49 (20.6%) | 30 (18.2%) | 51 (22.8%) | 45 (18.7%) | 36 (24.3%) | |||||

| poorly differentiated | 203 (52.2%) | 66 (50.0%) | 137 (53.3%) | 74 (49.0%) | 129 (54.2%) | 79 (47.9%) | 124 (55.4%) | 135 (56.0%) | 68 (45.9%) | |||||

| mucinous | 57 (14.7%) | 24 (18.1%) | 33 (12.8%) | 26 (17.2%) | 31 (13.0%) | 28 (16.9%) | 29 (12.9%) | 33 (13.7%) | 24 (16.2%) | |||||

| signetring cell | 29 (7.4%) | 8 (6.1%) | 21 (8.2%) | 9 (6.0%) | 20 (8.4%) | 13 (7.9%) | 16 (7.1%) | 18 (7.5%) | 11 (7.4%) | |||||

| Tumor grade | G1-G2 | 214 (55.0%) | 68 (51.5%) | 146 (56.8%) | 0.320 | 78 (51.7%) | 136 (58.0%) | 0.289 | 85 (51.5%) | 129 (57.6%) | 0.234 | 133 (55.2%) | 81 (54.7%) | 0.930 |

| G3-G4 | 175 (45.0%) | 64 (48.5%) | 111 (43.2%) | 73 (48.3%) | 102 (42.0%) | 80 (48.5%) | 95 (42.4%) | 108 (44.8%) | 67 (45.3%) | |||||

| Tumor stage | I-II | 159 (40.9%) | 95 (72.0%) | 64 (24.9%) | 0.000 | 78 (51.7%) | 81 (34.0%) | 0.001 | 83 (50.3%) | 76 (33.9%) | 0.001 | 72 (29.9%) | 87 (58.8%) | 0.000 |

| III-IV | 230 (59.1%) | 37 (28.0%) | 193 (75.1%) | 73 (48.3%) | 157 (66.0%) | 82 (49.7%) | 148 (66.1%) | 169 (70.1%) | 61 (41.2%) | |||||

| Depth of invasion | T1-T2 | 66 (17.0%) | 38 (28.8%) | 28 (10.9%) | 0.000 | 37 (24.5%) | 29 (12.2%) | 0.002 | 44 (26.7%) | 22 (9.8%) | 0.000 | 22 (9.1%) | 44 (29.7%) | 0.000 |

| T3-T4 | 323 (83%) | 94 (71.2%) | 229 (89.1%) | 114 (75.5%) | 209 (87.8%) | 121 (73.3%) | 202 (90.2%) | 219 (90.9%) | 104 (70.3%) | |||||

| Lymph node | N0 | 72 (18.5%) | 41 (31.1%) | 31 (12.1%) | 0.000 | 42 (27.8%) | 30 (12.6%) | 0.000 | 43 (26.1%) | 29 (12.9%) | 0.000 | 27 (11.2%) | 45 (30.4%) | 0.000 |

| N1-N3 | 317 (81.5%) | 91 (68.9%) | 226 (87.9%) | 109 (72.2%) | 208 (87.4%) | 122 (73.9%) | 195 (87.1%) | 214 (88.8%) | 103 (69.6%) | |||||

| Distant metastasis | M0 | 235 (60.4%) | 106 (80.3%) | 129 (50.2%) | 0.000 | 116 (76.8%) | 119 (50.0%) | 0.000 | 116 (70.3%) | 119 (53.1%) | 0.001 | 119 (49.4%) | 116 (78.4%) | 0.000 |

| M1 | 154 (39.6%) | 26 (19.7%) | 128 (49.8%) | 35 (23.2%) | 119 (50.0%) | 49 (29.7%) | 105 (46.9%) | 122 (50.6%) | 32 (21.6%) | |||||

| CEA (ng/ml) | ≤5 | 243 (62.5%) | 92 (69.7%) | 151 (58.8%) | 0.034 | 107 (70.9%) | 136 (57.1%) | 0.006 | 113 (68.5%) | 130 (58.0%) | 0.035 | 134 (55.6%) | 109 (73.6%) | 0.000 |

| >5 | 146 (37.5%) | 40 (30.3%) | 106 (41.2%) | 44 (29.1%) | 102 (42.9%) | 52 (31.5%) | 94 (42.0%) | 107 (44.4%) | 39 (26.4%) | |||||

| CA199 (U/ml) | ≤37 | 278 (71.5%) | 109 (82.6%) | 169 (65.8%) | 0.001 | 123 (81.5%) | 155 (65.1%) | 0.001 | 130 (78.8%) | 148 (66.1%) | 0.006 | 160 (66.4%) | 118 (79.7%) | 0.005 |

| >37 | 111 (28.5%) | 23 (17.4%) | 88 (34.2%) | 28 (18.5%) | 83 (34.9%) | 35 (21.2%) | 76 (33.9%) | 81 (33.6%) | 30 (20.3%) | |||||

NLR, neutrophil count to lymphocyte count; dNLR, neutrophil count to (white cell count – neutrophil count); PLR, platelet count to lymphocyte count; LMR, lymphocyte to monocyte ratio.

*Difference between groups was tested by Chi-square test.

aGrade 1 and 2 stand for high or middle differentiated tumor, grade 3 and 4 stand for poorly differentiated tumor.

bTumor stage according to seventh edition of American Joint of Committee on Cancer.

Figure 2.

The relationship between NLR, dNLR, PLR, LMR and tumor stage in patients with gastric cancer.

Table 3.

The association between patients’ pathological data and inflammatory biomarkers

| Variables | Tumor grade a | P * | Tumor stage b | P * | Depth of invasion | P * | Lymph node | P * | Distant metastasis | P * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1-G2 | G3-G4 | I-II | III-IV | T1-T2 | T3-T4 | N0 | N1-N3 | M0 | M1 | ||||||

| NLR | 6.51 ± 10.79 | 5.64 ± 6.81 | 0.512 | 4.73 ± 6.73 | 7.07 ± 10.50 | 0.000 | 4.02 ± 6.67 | 6.54 ± 9.60 | 0.000 | 4.81 ± 8.03 | 6.41 ± 9.45 | 0.000 | 5.00 ± 7.92 | 7.82 ± 10.70 | 0.000 |

| dNLR | 4.08 ± 5.94 | 3.51 ± 3.61 | 0.516 | 3.13 ± 3.63 | 4.31 ± 5.76 | 0.000 | 2.67 ± 3.24 | 4.06 ± 5.29 | 0.000 | 3.01 ± 3.92 | 4.01 ± 5.23 | 0.000 | 3.32 ± 4.51 | 4.61 ± 5.65 | 0.013 |

| PLR | 210 ± 248 | 169 ± 103 | 0.185 | 170 ± 121 | 207 ± 235 | 0.010 | 146 ± 135 | 201 ± 206 | 0.039 | 160 ± 137 | 199 ± 208 | 0.001 | 170 ± 122 | 225 ± 272 | 0.001 |

| LMR | 4.65 ± 3.73 | 4.95 ± 5.83 | 0.808 | 5.74 ± 5.93 | 4.13 ± 3.66 | 0.001 | 6.90 ± 8.55 | 4.36 ± 3.42 | 0.000 | 6.71 ± 8.31 | 4.35 ± 3.40 | 0.000 | 5.70 ± 5.79 | 3.39 ± 1.88 | 0.000 |

NLR, neutrophil count to lymphocyte count; dNLR, neutrophil count to (white cell count – neutrophil count); PLR, platelet count to lymphocyte count; LMR, lymphocyte to monocyte ratio

*Difference between groups was tested by Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis test.

aGrade 1 and 2 stand for high or middle differentiated tumor, grade 3 and 4 stand for poorly differentiated tumor.

bTumor stage according to seventh edition of American Joint of Committee on Cancer.

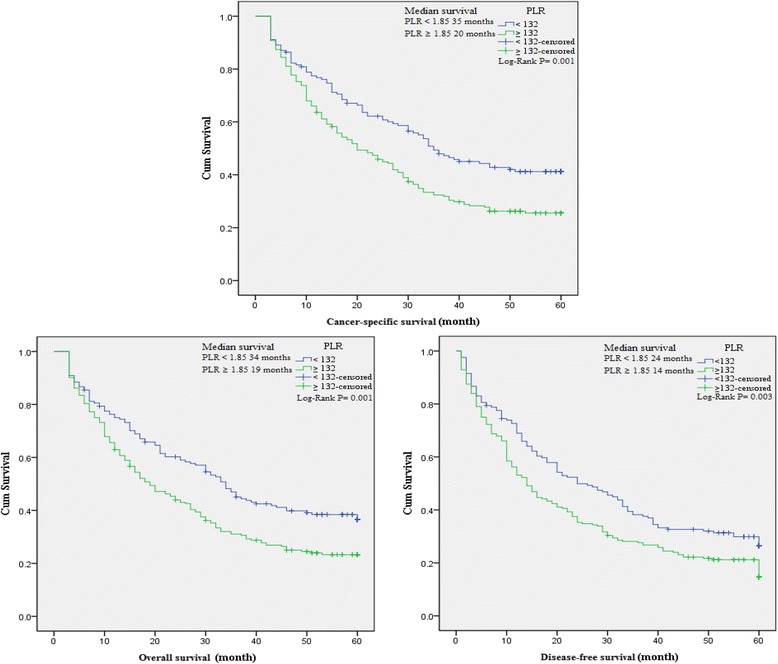

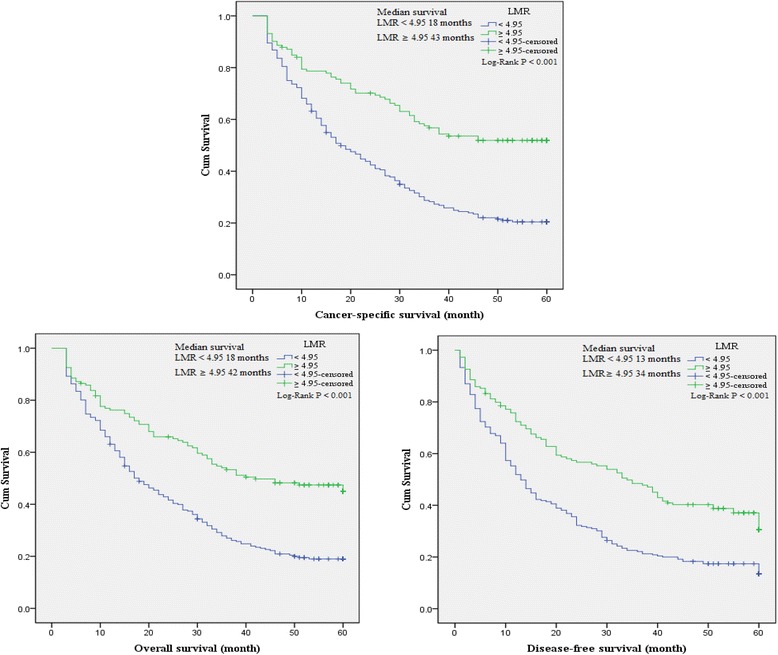

The association between baseline characteristics and clinical prognosis

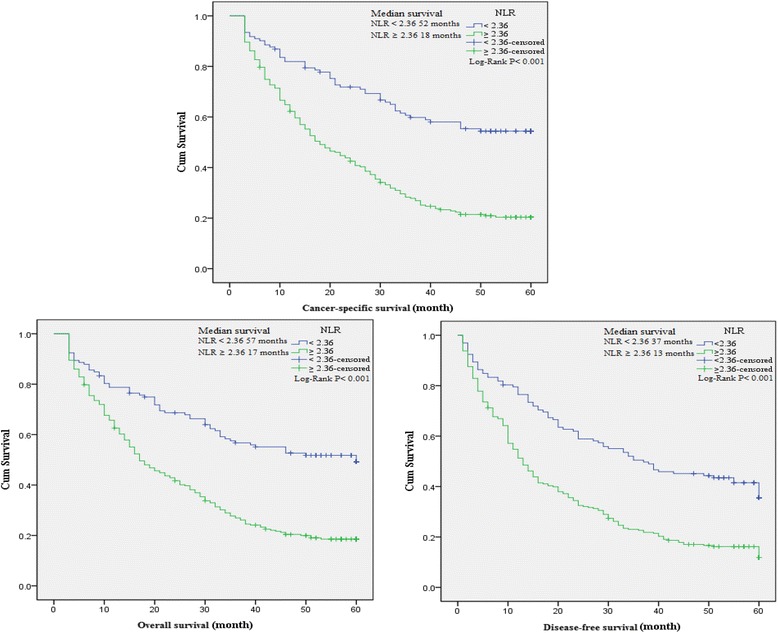

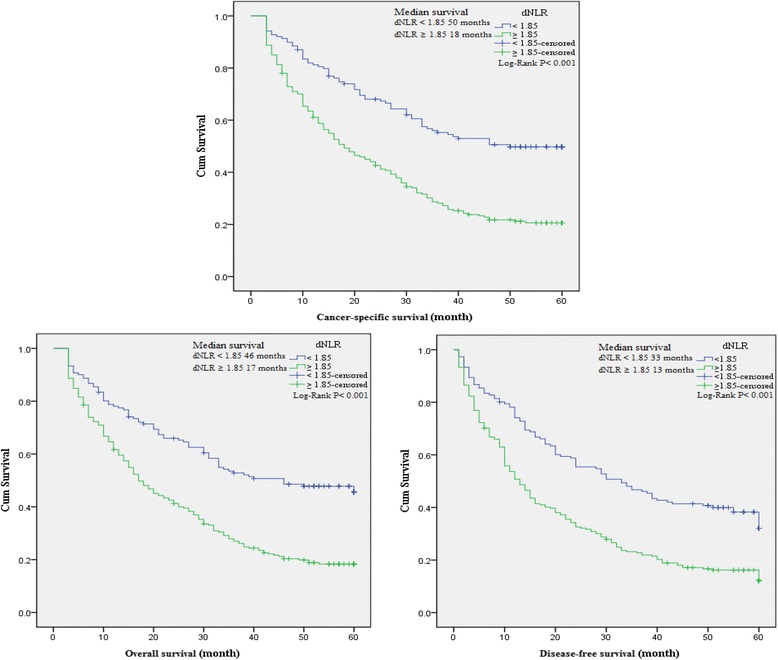

To evaluate the association of baseline characteristics with clinical prognosis, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank tests were performed based on the postoperative survival time and the pathological data of patients. Our results indicated that NLR (≥2.36), dNLR (≥1.85), PLR (≥132), LMR (<4.95), age of patients (≥65 years), tumor stage III-IV, depth of invasion T3-T4, lymph node N1-N3, distant metastasis M1, CEA (>5 ng/ml) and CA199 (>37 U/ml) were significantly associated with decreased OS, CSS and DFS, and GC family history of patients was also associated with decreased DFS as well as histological types (Table 4). In addition, a significant relationship between the inflammatory biomarkers (NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR) and clinical prognosis (OS, CSS and DFS) was observed (Figures 3, 4, 5, and 6).

Table 4.

The association of clinicopathological parameters with overall, cancer-specific and disease-free survival in patients

| Characteristics | Total | Overall survival | P* | Cancer-specific survival | P* | Disease-free survival | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n(%) 389 | n(%) of patients with death (n = 270) | n(%) of patients with death (n = 235) | n(%) of patients with recurrence (n = 302) | |||||

| Sex | Female | 107 (27.5%) | 72 (26.7%) | 0.518 | 66 (28.1%) | 0.629 | 80 (26.5%) | 0.279 |

| Male | 282 (72.5%) | 198 (73.3%) | 169 (71.9%) | 222 (73.5%) | ||||

| Age (years) | <65 | 185 (47.6%) | 111 (41.1%) | 0.000 | 98 (41.7%) | 0.000 | 132 (43.7%) | 0.001 |

| ≥65 | 204 (52.4%) | 159 (58.9%) | 137 (58.3%) | 170 (56.3%) | ||||

| Alcohol | Yes | 73 (18.8%) | 48 (17.8%) | 0.437 | 43 (18.3%) | 0.439 | 55 (18.2%) | 0.601 |

| No | 316 (81.2%) | 222 (82.2%) | 192 (81.7%) | 247 (81.8%) | ||||

| Tobacco | Yes | 72 (18.5%) | 56 (20.7%) | 0.152 | 49 (20.9%) | 0.125 | 61 (20.2%) | 0.326 |

| No | 317 (81.5%) | 214 (79.3%) | 186 (79.1%) | 241 (79.8%) | ||||

| Family history | Yes | 15 (3.9%) | 9 (3.3%) | 0.557 | 8 (3.4%) | 0.554 | 14 (4.6%) | 0.005 |

| No | 374 (96.1%) | 261 (96.7%) | 227 (96.6%) | 288 (95.4%) | ||||

| Histological type | papillary | 19 (4.9%) | 10 (3.7%) | 0.163 | 9 (3.8%) | 0.249 | 11 (3.6%) | 0.041 |

| tubular | 81 (20.8%) | 53 (19.6%) | 45 (19.1%) | 59 (19.5%) | ||||

| poorly differentiated | 203 (52.2%) | 148 (54.8%) | 126 (53.6%) | 165 (54.6%) | ||||

| mucinous | 57 (14.7%) | 37 (13.7%) | 35 (14.9%) | 43 (14.2%) | ||||

| signetring cell | 29 (7.4%) | 22 (8.1%) | 20 (8.5%) | 24 (7.9%) | ||||

| Tumor grade | G1-G2 | 214 (55.0%) | 139 (51.5%) | 0.061 | 127 (54.0%) | 0.168 | 159 (52.6%) | 0.044 |

| G3-G4 | 175 (45.0%) | 131 (48.5%) | 108 (46.0%) | 143 (47.4%) | ||||

| Tumor stage | I-II | 159 (40.9%) | 60 (22.2%) | 0.000 | 52 (22.1%) | 0.000 | 85 (28.1%) | 0.000 |

| III-IV | 230 (59.1%) | 210 (77.8%) | 183 (77.9%) | 217 (71.9%) | ||||

| Depth of invasion | T1-T2 | 66 (17.0%) | 18 (6.7%) | 0.000 | 16 (6.8%) | 0.000 | 35 (11.6%) | 0.000 |

| T3-T4 | 323 (83%) | 252 (93.3%) | 219 (93.2%) | 267 (88.4%) | ||||

| Lymph node | N0 | 72 (18.5%) | 17 (6.3%) | 0.000 | 15 (6.4%) | 0.000 | 34 (11.3%) | 0.000 |

| N1-N3 | 317 (81.5%) | 253 (93.7%) | 220 (93.6%) | 268 (88.7%) | ||||

| Distance metastasis | M0 | 235 (60.4%) | 121 (44.8%) | 0.000 | 106 (45.1%) | 0.000 | 150 (49.7%) | 0.000 |

| M1 | 154 (39.6%) | 149 (55.2%) | 129 (54.9%) | 152 (50.3%) | ||||

| CEA (ng/ml) | ≤5 | 243 (62.5%) | 149 (55.2%) | 0.000 | 131 (55.7%) | 0.000 | 176 (58.3%) | 0.000 |

| >5 | 146 (37.5%) | 121 (44.8%) | 104 (44.3%) | 126 (41.7%) | ||||

| CA199 (U/ml) | ≤37 | 278 (71.5%) | 175 (64.8%) | 0.000 | 151 (64.3%) | 0.000 | 203 (67.2%) | 0.000 |

| >37 | 111 (28.5%) | 95 (35.2%) | 84 (35.7%) | 99 (32.8%) | ||||

| NLR | <2.36 | 132 (33.9%) | 64 (23.7%) | 0.000 | 54 (23.0%) | 0.000 | 81 (26.8%) | 0.000 |

| ≥2.36 | 257 (66.1%) | 206 (76.3%) | 181 (77.0%) | 221 (73.2%) | ||||

| dNLR | <1.85 | 151 (38.8%) | 79 (29.3%) | 0.000 | 68 (28.9%) | 0.000 | 98 (32.5%) | 0.000 |

| ≥1.85 | 238 (61.2%) | 191 (70.7%) | 167 (71.1%) | 204 (67.5%) | ||||

| PLR | <132 | 165 (42.4%) | 100 (37.0%) | 0.001 | 83 (35.3%) | 0.001 | 117 (38.7%) | 0.002 |

| ≥132 | 224 (57.6%) | 170 (63.0%) | 152 (64.7%) | 185 (61.3%) | ||||

| LMR | <4.95 | 241 (71.0%) | 192 (71.1%) | 0.000 | 173 (73.6%) | 0.000 | 205 (67.9%) | 0.000 |

| ≥4.95 | 148 (29.0%) | 78 (29.9%) | 62 (26.4%) | 97 (32.1%) | ||||

NLR, neutrophil count to lymphocyte count; dNLR, neutrophil count to (white cell count – neutrophil count); PLR, platelet count to lymphocyte count; LMR, lymphocyte to monocyte ratio.

*Difference between two groups was tested by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Log-rank test.

aGrade 1 and 2 stand for high or middle differentiated tumor, grade 3 and 4 stand for poorly differentiated tumor.

bTumor stage according to seventh edition of American Joint of Committee on Cancer.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall, cancer-specific and disease-free survival probability according to NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR level. Patients with NLR ≥ 2.36 had a significantly associated with worse overall, cancer-specific and disease-free survival than those with NLR < 2.36.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall, cancer-specific and disease-free survival probability according to NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR level. Overall, cancer-specific and disease-free survival with dNLR ≥ 1.85 was shorter than those with dNLR < 1.85.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall, cancer-specific and disease-free survival probability according to NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR level. There was a significantly shorter overall, cancer-specific and disease-free survival in the group with PLR ≥ 132 than the group with PLR < 132.

Figure 6.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall, cancer-specific and disease-free survival probability according to NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR level. Patients with LMR ≥ 4.95 showed a longer overall, cancer-specific and disease-free survival than those with LMR < 4.95.

Clinicopathological parameters for the prediction of clinical prognosis were further investigated by univariate analysis with Cox regression model. The significant parameters in univariate analysis combined with sex and age were then used to determine the influence on OS, CSS and DFS by multivariate analysis. Our results revealed that age, tumor stage, lymph node and distant metastasis were significantly associated with reduced OS and CSS (Pall < 0.01; Table 5). More importantly, elevated NLR (HR = 1.53, P = 0.010) and dNLR (HR = 1.42, P = 0.012) were also associated with reduced CSS and OS, respectively. Meanwhile, NLR (HR = 1.38, P = 0.025), GC family history (HR = 2.13, P = 0.007), tumor stage (HR = 2.04, P = 0.000), distant metastasis (HR = 2.06, P = 0.000) and CA199 (HR = 1.33, P = 0.028) were considered to be independent indicators for DFS of GC patients.

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of overall, cancer-specific and disease-free survival by Cox regression model

| Variables | Overall survival | Cancer-specific survival | Disease-free survival | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||

| HR | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Sex (male) | 0.92 | 0.525 | 0.93 | 0.634 | 0.87 | 0.290 | ||||||

| Age (≥65 years) | 1.7 | 0.000 | 1.41 (1.10-1.80) | 0.007 | 1.73 | 0.000 | 1.51 (1.16-1.96) | 0.002 | 1.48 | 0.001 | 1.19 (0.94-1.50) | 0.146 |

| Alcohol (yes) | 0.89 | 0.445 | 0.88 | 0.446 | 0.93 | 0.609 | ||||||

| Tobacco (yes) | 1.24 | 0.160 | 1.27 | 0.133 | 1.15 | 0.336 | ||||||

| Family history (yes) | 1.22 | 0.564 | 0.81 | 0.561 | 0.561 | 2.09 | 0.007 | 2.13 (1.23-3.69) | 0.007 | |||

| Histological type | ||||||||||||

| Papillary | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Non-papillary | 1.83 | 0.061 | 1.77 | 0.093 | 1.89 | 0.038 | 1.42 (0.77-2.62) | 0.260 | ||||

| Tubular | 1.54 | 0.213 | 1.51 | 0.263 | 1.58 | 0.166 | ||||||

| Poorly differentiated | 1.93 | 0.045 | 1.66 (0.86-3.19) | 0.129 | 1.88 | 0.069 | 2.06 | 0.020 | 1.62 (0.88-3.01) | 0.124 | ||

| Mucinous | 1.72 | 0.127 | 1.68 | 0.166 | 1.66 | 0.135 | ||||||

| Signetring cell | 2.39 | 0.022 | 1.78 (0.83-3.79) | 0.137 | 2.09 | 0.066 | 2.33 | 0.021 | 1.91 (0.93-3.91) | 0.078 | ||

| Tumor grade (G3-G4) | 1.25 | 0.066 | 1.19 | 0.175 | 1.26 | 0.049 | 1.19 (0.93-1.50) | 0.162 | ||||

| Tumor stage (III-IV) | 4.87 | 0.000 | 2.18 (1.48-3.22) | 0.000 | 5.45 | 0.000 | 2.46 (1.62-3.72) | 0.000 | 3.58 | 0.000 | 2.04 (1.46-2.84) | 0.000 |

| Depth of invasion (T3-T4) | 4.58 | 0.000 | 1.22 (0.67-2.22) | 0.511 | 4.78 | 0.000 | 1.18 (0.63-2.21) | 0.597 | 2.48 | 0.000 | 0.81 (0.50-1.32) | 0.405 |

| Lymph node (N1-N3) | 5.6 | 0.000 | 2.34 (1.35-4.05) | 0.003 | 5.36 | 0.000 | 2.12 (1.21-3.74) | 0.009 | 3.05 | 0.000 | 1.39 (0.91-2.14) | 0.132 |

| Distant metastasis (M1) | 4.61 | 0.000 | 2.14 (1.56-2.93) | 0.000 | 5.07 | 0.000 | 2.09 (1.50-2.92) | 0.000 | 3.73 | 0.000 | 2.06 (1.52-2.81) | 0.000 |

| CEA (>5 ng/ml) | 1.66 | 0.000 | 0.87 (0.67-1.14) | 0.323 | 1.74 | 0.000 | 0.93 (0.70-1.24) | 0.610 | 1.53 | 0.000 | 0.85 (0.66-1.11) | 0.237 |

| CA199 (>37 U/ml) | 1.95 | 0.000 | 1.16 (0.89-1.51) | 0.275 | 2.14 | 0.000 | 1.30 (0.98-1.72) | 0.065 | 1.92 | 0.000 | 1.33 (1.03-1.72) | 0.028 |

| NLR (≥2.36) | 2.34 | 0.000 | 1.13 (0.68-1.87) | 0.648 | 2.56 | 0.000 | 1.53 (1.11-2.11) | 0.010 | 2.10 | 0.000 | 1.38 (1.04-1.82) | 0.025 |

| dNLR (≥1.85) | 2.12 | 0.000 | 1.42 (1.08-1.87) | 0.012 | 2.23 | 0.000 | 1.10 (0.66-1.85) | 0.713 | 1.92 | 0.000 | 1.08 (0.69-1.69) | 0.722 |

| PLR (≥132) | 1.51 | 0.001 | 1.03 (0.78-1.35) | 0.858 | 1.56 | 0.001 | 0.96 (0.71-1.28) | 0.763 | 1.42 | 0.003 | 0.94 (0.72-1.23) | 0.674 |

| LMR (≥4.95) | 0.49 | 0.000 | 1.00 (0.73-1.35) | 0.977 | 0.44 | 0.000 | 1.00 (0.71-1.40) | 0.995 | 0.55 | 0.000 | 0.98 (0.73-1.32) | 0.907 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; NLR, neutrophil count to lymphocyte count; dNLR, neutrophil count to (white cell count – neutrophil count); PLR, platelet count to lymphocyte count; LMR, lymphocyte to monocyte ratio.

aGrade 1 and 2 stand for high or middle differentiated tumor, grade 3 and 4 stand for poorly differentiated tumor.

bTumor stage according to seventh edition of American Joint of Committee on Cancer.

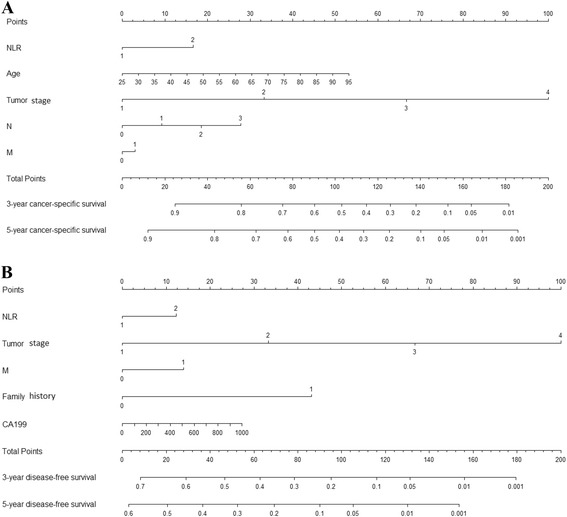

Prognostic nomograms for CSS and DFS

To predict the survival of GC patients after surgical resection, prognostic nomograms were depicted by Cox regression model analysis using all the significant independent indicators for CSS and DFS (Figure 7). These nomograms can predict the probability of recurrence or death for GC patients within 3 or 5 years after initial surgery, assuming the patient does not die of another cause first. The c-index for CSS and DFS prediction were 0.89 and 0.85, respectively.

Figure 7.

Postoperative nomogram with NLR, dNLR and significant clinicopathologic characteristics predicted the probability of gastric cancer for cancer-specific survival (A) and disease-free survival (B). To use the nomogram, an individual GC patient’s value is located on each variable axis, and a line is depicted upward to determine the number of points received for each variable value. Subsequently the sum of these numbers is located on Total Points axis, and a line is drawn downward to the survival axes to determine the likelihood of 3- or 5-year survival for CSS or DFS.

Discussion

The present study showed that pre-operation NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR in the peripheral blood of GC patients were significantly associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis after surgical resection. Despite substantial progress in the understanding of the association between NLR, dNLR, PLR, LMR and the prognosis for cancers [11,21,27-29], previous studies only focused on the influence of one or two biomarkers on prognosis. This study was the first attempt to evaluate the prognosis of patients with GC based on these four biomarkers and to establish a predictive nomogram to improve the predictive accuracy.

The relationship between inflammation and cancer was first reported by Rudolf Virchow in 1863, who suggested that “lymphoreticular infiltrate” reflected the origin of cancer at the sites of chronic inflammation [6]. Over the past decades, Virchow’s hypothesis was verified by emerging evidence showing the influence of inflammatory microenvironment on cancer. More understanding of the links between inflammation and cancer contributes to the prevention and treatment of tumor. Consequently, several biomarkers have been reported to reflect the link between inflammation and cancer, such as interferon-gamma/interleukin-4 ratio [28] and inflammation-based prognostic score (Glasgow prognostic score) based on CRP and albumin levels [30]. Previous studies have shown that the systemic inflammatory biomarkers (NLR, dNLR, PLR, and LMR) can be also considered as potential prognostic factors for different types of carcinoma [24,31-33]. This study also indicated that OS, CSS, and DFS were obviously reduced in the high NLR, dNLR and PLR groups, but were decreased in the low LMR group. In multivariate analysis, dNLR showed a significant association with OS, and NLR was closely associated with CSS and DFS. The above results were supported by several mechanisms of inflammatory reaction to tumor.

Firstly, elevated neutrophils can secrete large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which induce cell DNA damage and genetic instability, causing both carcinogenesis and promotion in tumor microenvironment [34]. Elevated circulating neutrophils have been particularly reported to contain and secrete pro-angiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Circulating VEGF contributes to tumor angiogenesis and the progression of neoplasm [35,36]. VEGF was observed to be significantly overexpressed in gastric cancer tissue compared with normal tissue [37], and it has been verified that the overexpression of VEGF can induce cell proliferation and promoted cell cycle of GC cells by increasing the activation of VEGF receptor 2 in vitro [38]. On the other hand, neutrophilia was triggered by cancer-related inflammatory factors, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6, granulocyte colony stimulating factor, and myeloid growth factors [39-42].

Secondly, the decreased lymphocyte count and function play important roles in inflammatory reaction to tumor. It has been reported that neutrophil could inhibit T cell activation through the production of nitric oxide, arginase, and ROS [43], leading to depletion of lymphocyte-mediated immune response. This can explain why increased NLR may act as an independently prognostic factor for CSS due to elevated neutrophil and relative lymphocytopenia [44]. Previous study has proven that the density of tumor-associated macrophages in various cancers is correlated with increased angiogenesis, tumor invasion, and poor prognosis [45]. Tumor-associated macrophages derived from circulating monocytes are selectively released to tumor microenvironment by locally surged chemokines [4]. Thus, the circulating level of monocytes shows a surrogate for the formation or presence of tumor-associated macrophages.

In the present study, the optimal cut-off levels of NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR calculated by ROC curves based on CSS were quite similar to those on the basis of OS and DFS, indicating that CSS could also be applied to calculate the optimal cut-off levels of NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR. Indeed, some recent studies have employed CSS as an end-point to achieve the optimal cut-off point [24-26]. In the present study, it was observed that the optimal cut-off value of 2.36 for NLR was a superior prognostic level based on HR, which had the highest AUC and the best sensitivity and specificity. However, the optimal cut-off level for NLR in this study was inconsistent with the results of previous studies [11,20,21], which may be due to the differences in assays measuring neutrophil and lymphocyte, different population and different survival end-point for NLR [13,46].

Some nomograms have been developed in various cancers [47-49], and nomograms have shown to be more accurate than the conventional staging systems for predicting prognosis in cancers [50,51]. The present study attempts to establish a predictive nomogram to predict the probability of postoperative patients who will relapse and die of GC within 3-year and 5-year based on NLR, dNLR and clinicopathological factors. The nomograms performed well in predicting CSS and DFS, and their predictions were supported by c-index (0.89 and 0.85, respectively). These results supported that the nomograms could better predict prognosis in patients with GC post operation.

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. Firstly, the study was a retrospective design, with a small population size of 389 patients, which lead to no association between histological types and clinical prognosis. Secondly, the peripheral blood findings were not compared to the findings of peritumoral inflammation in the primary tumor tissue. Nevertheless, the peripheral blood results provide a novel horizon to understand the roles of NLR in carcinogenesis. Finally, there was some heterogeneity in the treatment used for patients after surgical resection, which led to different clinical prognosis. Hence, further studies are needed to illuminate the relationship between inflammatory biomarkers and prognosis in patients with GC.

Conclusions

Preoperative NLR, dNLR, PLR and LMR are significantly associated with poor prognosis. Moreover, dNLR and NLR are independent prognostic indicators for OS and DFS, respectively, and NLR is a superior independent prognostic factor for CSS in surgical patients with GC. Therefore, integrate NLR, dNLR and the predictive nomogram could be used to evaluate prognosis and offer optimal therapeutic strategy.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grants from The National Nature Science Foundation of China (no. 81172141, 81200401), Nanjing Science and Technology Committee Project (no.201108025), Nanjing Medical Technology Development Project (no. ZKX11025), Nanjing Health Young Talent Project, Jiangsu Provincial Key Medical Talents to S.K.W., Nanjing Medical Science and Technique Development Foundation to Y.Q.P. (no. QRX11255, YKK13107) and B.S.H. (no. QRX11254, QYK11175, JQX13003). We thank Professor William C. Cho of Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong, China, for revising our manuscript.

Footnotes

Qiwen Deng and Bangshun He contributed equally to this work.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: SKW, QWD and BSH. Performed the experiments: QWD, HLS, YQP, JC, XL, HQY, JY and FW. Analyzed the data: BSH, XL and QWD. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: HLS and YQX. Wrote the manuscript: SKW, QWD and BSH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Qiwen Deng and Bangshun He are co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Qiwen Deng, Email: qiw_deng@163.com.

Bangshun He, Email: 1061851556@qq.com.

Xian Liu, Email: 2697250365@qq.com.

Jin Yue, Email: jinjun_hou@163.com.

Houqun Ying, Email: 570154244@qq.com.

Yuqin Pan, Email: 2339820358@qq.com.

Huiling Sun, Email: sunhuiling1988@yeah.net.

Jie Chen, Email: tiany_gao@163.com.

Feng Wang, Email: 18262638632@139.com.

Tianyi Gao, Email: love857_qiwendeng@163.com.

Lei Zhang, Email: 303794458@qq.com.

Shukui Wang, Email: shukwang@163.com.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoo CH, Noh SH, Shin DW, Choi SH, Min JS. Recurrence following curative resection for gastric carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2000;87:236–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee K, Hwang H, Nam KT. Immune response and the tumor microenvironment: how they communicate to regulate gastric cancer. Gut Liver. 2014;8:131–9. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2014.8.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoppacciaro A, Melani C, Parenza M, Mastracchio A, Bassi C, Baroni C, et al. Regression of an established tumor genetically modified to release granulocyte colony-stimulating factor requires granulocyte-T cell cooperation and T cell-produced interferon gamma. J Exp Med. 1993;178:151–61. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellocq A, Antoine M, Flahault A, Philippe C, Crestani B, Bernaudin JF, et al. Neutrophil alveolitis in bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: induction by tumor-derived interleukin-8 and relation to clinical outcome. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:83–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Larco JE, Wuertz BR, Furcht LT. The potential role of neutrophils in promoting the metastatic phenotype of tumors releasing interleukin-8. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4895–900. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghasemzadeh M, Hosseini E. Platelet-leukocyte crosstalk: Linking proinflammatory responses to procoagulant state. Thromb Res. 2013;131:191–7. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho IR, Park JC, Park CH, Jo JH, Lee HJ, Kim S, Shim CN, Lee H, Shin SK, Lee SK, Lee YC. Pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker to predict chemotherapeutic response and survival outcomes in metastatic advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17(4):703–10. doi: 10.1007/s10120-013-0330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halazun KJ, Aldoori A, Malik HZ, Al-Mukhtar A, Prasad KR, Toogood GJ, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival following hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh BS, Jang JW, Kwon JH, You CR, Chung KW, Kay CS, et al. Prognostic value of C-reactive protein and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarraf KM, Belcher E, Raevsky E, Nicholson AG, Goldstraw P, Lim E. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and its association with survival after complete resection in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:425–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Murri AM, Wilson C, Lannigan A, Doughty JC, Angerson WJ, McArdle CS, et al. Evaluation of the relationship between the systemic inflammatory response and cancer-specific survival in patients with primary operable breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:891–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamieson NB, Glen P, McMillan DC, McKay CJ, Foulis AK, Carter R, et al. Systemic inflammatory response predicts outcome in patients undergoing resection for ductal adenocarcinoma head of pancreas. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:21–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirashima M, Higuchi S, Sakamoto K, Nishiyama T, Okada H. The ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes and the phenotypes of neutrophils in patients with early gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1998;124:329–34. doi: 10.1007/s004320050178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamanaka T, Matsumoto S, Teramukai S, Ishiwata R, Nagai Y, Fukushima M. The baseline ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes is associated with patient prognosis in advanced gastric cancer. Oncology. 2007;73:215–20. doi: 10.1159/000127412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toge T, Yamaguchi Y. Protein-bound polysaccharide increases survival in resected gastric cancer cases stratified with a preoperative granulocyte and lymphocyte count. Oncol Rep. 2000;7:1157–61. doi: 10.3892/or.7.5.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gwak MS, Choi SJ, Kim JA, Ko JS, Kim TH, Lee SM, et al. Effects of gender on white blood cell populations and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio following gastrectomy in patients with stomach cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22(Suppl):S104–8. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.S.S104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung MR, Park YK, Jeong O, Seon JW, Ryu SY, Kim DY, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts poor survival following resection in late stage gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:504–10. doi: 10.1002/jso.21986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Washington K. 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3077–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1362-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greiner M, Pfeiffer D, Smith RD. Principles and practical application of the receiver-operating characteristic analysis for diagnostic tests. Prev Vet Med. 2000;45:23–41. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(00)00115-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Proctor MJ, McMillan DC, Morrison DS, Fletcher CD, Horgan PG, Clarke SJ. A derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:695–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutterer GC, Stoeckigt C, Stojakovic T, Jesche J, Eberhard K, Pummer K, Zigeuner R, Pichler M. Low preoperative lymphocyte-monocyte ratio (LMR) represents a potentially poor prognostic factor in nonmetastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2014;32(7):1041–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dalpiaz O, Pichler M, Mannweiler S, Martin Hernandez JM, Stojakovic T, Pummer K, et al. Validation of the pretreatment derived neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in a European cohort of patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2531–6. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimada H, Takiguchi N, Kainuma O, Soda H, Ikeda A, Cho A, et al. High preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts poor survival in patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13:170–6. doi: 10.1007/s10120-010-0554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ubukata H, Motohashi G, Tabuchi T, Nagata H, Konishi S. Evaluations of interferon-gamma/interleukin-4 ratio and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio as prognostic indicators in gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:742–7. doi: 10.1002/jso.21725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dutta S, Crumley AB, Fullarton GM, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. Comparison of the prognostic value of tumour and patient related factors in patients undergoing potentially curative resection of gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2012;204:294–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crumley AB, McMillan DC, McKernan M, McDonald AC, Stuart RC. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score in patients with inoperable gastro-oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:637–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satomi A, Murakami S, Ishida K, Mastuki M, Hashimoto T, Sonoda M. Significance of increased neutrophils in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 1995;34:69–73. doi: 10.3109/02841869509093641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koh YW, Park CS, Yoon DH, Suh C, Huh J. Should the cut-off values of the lymphocyte to monocyte ratio for prediction of prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma be changed in elderly patients? Eur J Haematol 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Kemal Y, Yucel I, Ekiz K, Demirag G, Yilmaz B, Teker F, et al. Elevated Serum Neutrophil to Lymphocyte and Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratios Could be Useful in Lung Cancer Diagnosis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:2651–4. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.6.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weitzman SA, Gordon LI. Inflammation and cancer: role of phagocyte-generated oxidants in carcinogenesis. Blood. 1990;76:655–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kusumanto YH, Dam WA, Hospers GA, Meijer C, Mulder NH. Platelets and granulocytes, in particular the neutrophils, form important compartments for circulating vascular endothelial growth factor. Angiogenesis. 2003;6:283–7. doi: 10.1023/B:AGEN.0000029415.62384.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shamamian P, Schwartz JD, Pocock BJ, Monea S, Whiting D, Marcus SG, et al. Activation of progelatinase A (MMP-2) by neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, and proteinase-3: a role for inflammatory cells in tumor invasion and angiogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2001;189:197–206. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li L, Wang L, Song P, Geng X, Liang X, Zhou M, et al. Critical role of histone demethylase RBP2 in human gastric cancer angiogenesis. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:81. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J, Wang P, Zhu J, Wang W, Yin J, Zhang C, et al. SPARC expression is negatively correlated with clinicopathological factors of gastric cancer and inhibits malignancy of gastric cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2014;31:2312–20. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuper H, Adami HO, Trichopoulos D. Infections as a major preventable cause of human cancer. J Intern Med. 2000;248:171–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blaser MJ, Chyou PH, Nomura A. Age at establishment of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer risk. Cancer Res. 1995;55:562–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scholl SM, Pallud C, Beuvon F, Hacene K, Stanley ER, Rohrschneider L, et al. Anti-colony-stimulating factor-1 antibody staining in primary breast adenocarcinomas correlates with marked inflammatory cell infiltrates and prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:120–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGuire L, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Depressive symptoms and lymphocyte proliferation in older adults. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:192–7. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muller I, Munder M, Kropf P, Hansch GM. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils and T lymphocytes: strange bedfellows or brothers in arms? Trends Immunol. 2009;30:522–30. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohtani H. Focus on TILs: prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Immun. 2007;7:4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mantovani A, Schioppa T, Porta C, Allavena P, Sica A. Role of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor progression and invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:315–22. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Solomon P, O’Brien K, Wilkins S, Gervais N. Aging with HIV and disability: the role of uncertainty. AIDS Care. 2014;26:240–5. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.811209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bochner BH, Kattan MW, Vora KC. Postoperative nomogram predicting risk of recurrence after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3967–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karakiewicz PI, Briganti A, Chun FK, Trinh QD, Perrotte P, Ficarra V, et al. Multi-institutional validation of a new renal cancer-specific survival nomogram. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1316–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deng Q, He B, Gao T, Pan Y, Sun H, Xu Y, et al. Up-regulation of 91H promotes tumor metastasis and predicts poor prognosis for patients with colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sternberg CN. Are nomograms better than currently available stage groupings for bladder cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3819–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Touijer K, Scardino PT. Nomograms for staging, prognosis, and predicting treatment outcomes. Cancer. 2009;115:3107–11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]