The interdependence of some microbes and their hosts is profound. Coevolution has led to hosts whose survival and reproduction is dependent upon the presence of a specific microbial partner, and to microbes that have adapted to life within hosts. Such obligate microbial symbioses are present across the tree of life, and study of associations between insects and microbes have provided key insights into the evolutionary, ecological, physiological, and molecular underpinnings of these associations. In PNAS, Moran and Yun (1) take a novel approach to investigate one of the best-studied insect-symbiont associations, that of aphids and the bacterium Buchnera aphidicola. By replacing one symbiont for another, the authors experimentally confirm that an important ecological phenotype is dictated by the genetic make-up of the symbiont and pave the way for future studies on host and symbiont interactions (Fig. 1).

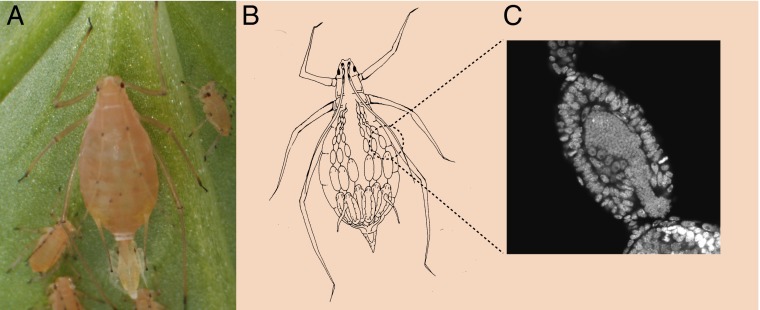

Fig. 1.

Developmental biology of a symbiotic model. (A) A pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum) giving live birth to a clonal daughter. (B) Drawing of an aphid illustrating chains of embryos at various developmental stages. (C) Confocal microscopic image of an aphid embryo being infiltrated by small spherical cells of Buchnera aphidicola symbionts (image courtesy of Shuji Shigenobu). Moran and Yun (1) take advantage of this developmental process by depleting aphids of an established Buchnera strain then introducing another strain into mothers during the window when embryos are forming associations with their obligate microbial partner.

Research on the aphid-Buchnera symbiosis, as well as other insect symbioses, builds upon elegant microscopic study of the microbes living inside insects (2). These early investigations revealed that many insects harbor specific microbes and pass them faithfully onto offspring, suggesting that selection and adaptation have shaped maintenance of these influential partnerships.

One consequence of symbiotic evolution, however, hampers investigation. Because of adaptation to a within-host lifestyle, many obligate microbial symbionts are not cultivable outside of their hosts, precluding classic microbiological and genetic approaches of inquiry. This hurdle has been partially overcome by using cultivation-independent gene sequencing to reveal phylogenetic patterns of host and microbe associations (3–6) and genome sequencing to reveal symbionts’ genetic capacities to provision and protect hosts (7–10). For aphids and Buchnera, congruence of host and symbiont phylogenies suggests a long history of coevolution and cospeciation (5, 11). Genome sequencing of Buchnera strains (12–14) and aphid hosts (15) confirms the capacity of Buchnera to produce nutrients that aphids do not obtain from their amino acid-deficient plant sap diet. These genomic insights have been complemented by experimental studies of the insects’ and microbes’ complex metabolic (16, 17) and developmental (18–20) integration. Taking these data together, this research illustrates the intricate interdependence of host and symbiont.

If host and microbial lineages within obligate symbioses are specifically adapted to one another, then disassociating these partnerships should be unlikely. This explains the congruence of host and symbiont phylogenies in many systems (3–6), as one obligate symbiont lineage rarely replaces another. For symbiont replacement to occur, at the within-host level, a novel microbe must be able to outcompete the established, presumably host-adapted symbiont. The novel microbe must also be able to use available transmission routes, which are limited in such cases as the aphid–Buchnera symbiosis, where microbes are internally vertically transmitted from mother to offspring. Then, at the population level, individuals harboring novel symbionts must have high enough fitness relative to individuals harboring coevolved symbionts that the novel symbiosis can be maintained in the population in the face of selection. Because symbiont replacement does happen over evolutionary timescales in some systems (21, 22), these conditions are met occasionally, but they are rare.

Given the requirements for symbiont replacement, it would be easy for researchers to say, “if it hardly ever happens in nature, we certainly can’t do it in the lab.” In science, however, as well as much of life, it is important to not maintain fixed ideas of what won’t work. Moran and Yun (1) exploit the process of mother-to-daughter vertical symbiont transmission and experimental selection to replace one obligate symbiont with another. With knowledge that the cool temperatures of laboratory-rearing conditions frequently lead to fixation of a mutation in the promoter of a Buchnera gene encoding a heat-shock protein, making the symbiont less resistant to heat stress (23), they heat stress aphids (and their internally developing embryos), greatly reducing the established Buchnera population. The authors then transfer a heat-resistant Buchnera strain from a donor aphid at the time when symbionts are typically infiltrating developing embryos. This process provides a temporal window of opportunity for the new symbiont to establish. Further exposing the aphids to high temperatures, Moran and Yun select for aphid–Buchnera pairs with the heat-resistant symbiont, as harboring the heat-resistant symbiont increases aphid fitness under high temperature conditions. It works. In replicate experiments, the novel symbiont strain either replaced the established symbiont strain entirely or was able to coexist with the established strain.

This result provides a jumping off point for new lines of inquiry in this model system of symbiosis research. The ability to replace one obligate symbiont with another allows for controlled experimental confirmation of whether ecologically relevant phenotypes, such as the ability to persist under heat stress or in the absence of certain nutrients, are indeed a consequence of a symbiont’s genotype. Furthermore, placement of alternative symbiont lineages in the same host background, and the same symbiont lineage in alternative host backgrounds, facilitates study of the impact of host genotype by symbiont genotype interactions on the establishment, maintenance, and benefits of obligate symbiotic associations. One can, for example, determine whether adaptation on the part of host lineages to specific symbiont lineages makes hosts recalcitrant to acceptance of symbionts distantly related to their typical partners. This mechanism of symbiont replacement could also provide a useful tool in molecular genetics if mutagenized symbionts could be introduced into alternative hosts.

Although exploitation of the heat-susceptibility of laboratory-passaged Buchnera strains is a tool specific to the aphid–Buchnera system, this work highlights a basic, important lesson. As much as possible, scientists must consider their systems from as many perspectives as possible. In this case, fundamental knowledge of the process by which symbionts are integrated during embryonic development revealed a potentially exploitable route of transmission. Knowledge of a genetic mutation provided a mechanism of symbiont selection. The coupling of these seemingly disparate pieces of knowledge led to creation of a new research tool.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 2093.

References

- 1.Moran NA, Yun Y. Experimental replacement of an obligate insect symbiont. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:2093–2096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420037112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchner P. Endosymbiosis of Animals with Plant Microorganisms. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hosokawa T, Kikuchi Y, Nikoh N, Shimada M, Fukatsu T. Strict host-symbiont cospeciation and reductive genome evolution in insect gut bacteria. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(10):e337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X, Li S, Aksoy S. Concordant evolution of a symbiont with its host insect species: Molecular phylogeny of genus Glossina and its bacteriome-associated endosymbiont, Wigglesworthia glossinidia. J Mol Evol. 1999;48(1):49–58. doi: 10.1007/pl00006444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark MA, Moran NA, Baumann P, Wernegreen JJ. Cospeciation between bacterial endosymbionts (Buchnera) and a recent radiation of aphids (Uroleucon) and pitfalls of testing for phylogenetic congruence. Evolution. 2000;54(2):517–525. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thao ML, et al. Cospeciation of psyllids and their primary prokaryotic endosymbionts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66(7):2898–2905. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.7.2898-2905.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCutcheon JP, McDonald BR, Moran NA. Convergent evolution of metabolic roles in bacterial co-symbionts of insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(36):15394–15399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906424106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCutcheon JP, Moran NA. Parallel genomic evolution and metabolic interdependence in an ancient symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(49):19392–19397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708855104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen AK, Vorburger C, Moran NA. Genomic basis of endosymbiont-conferred protection against an insect parasitoid. Genome Res. 2012;22(1):106–114. doi: 10.1101/gr.125351.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikoh N, Hosokawa T, Oshima K, Hattori M, Fukatsu T. Reductive evolution of bacterial genome in insect gut environment. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:702–714. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumann P, et al. Genetics, physiology, and evolutionary relationships of the genus Buchnera: Intracellular symbionts of aphids. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:55–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shigenobu S, Watanabe H, Hattori M, Sakaki Y, Ishikawa H. Genome sequence of the endocellular bacterial symbiont of aphids Buchnera sp. APS. Nature. 2000;407(6800):81–86. doi: 10.1038/35024074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang Z, et al. Comparative analysis of genome sequences from four strains of the Buchnera aphidicola Mp endosymbion of the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:917. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamelas A, Gosalbes MJ, Moya A, Latorre A. New clues about the evolutionary history of metabolic losses in bacterial endosymbionts, provided by the genome of Buchnera aphidicola from the aphid Cinara tujafilina. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(13):4446–4454. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00141-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Aphid Genomics Consortium Genome sequence of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(2):e1000313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell CW, Bouvaine S, Newell PD, Douglas AE. Shared metabolic pathways in a coevolved insect-bacterial symbiosis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(19):6117–6123. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01543-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price DRG, et al. Aphid amino acid transporter regulates glutamine supply to intracellular bacterial symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(1):320–325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306068111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koga R, Meng X-Y, Tsuchida T, Fukatsu T. Cellular mechanism for selective vertical transmission of an obligate insect symbiont at the bacteriocyte-embryo interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(20):E1230–E1237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119212109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braendle C, et al. Developmental origin and evolution of bacteriocytes in the aphid-Buchnera symbiosis. PLoS Biol. 2003;1(1):E21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miura T, et al. A comparison of parthenogenetic and sexual embryogenesis of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum (Hemiptera: Aphidoidea) J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol. 2003;295(1):59–81. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duron O, et al. Origin, acquisition and diversification of heritable bacterial endosymbionts in louse flies and bat flies. Mol Ecol. 2014;23(8):2105–2117. doi: 10.1111/mec.12704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koga R, Bennett GM, Cryan JR, Moran NA. Evolutionary replacement of obligate symbionts in an ancient and diverse insect lineage. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15(7):2073–2081. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunbar HE, Wilson ACC, Ferguson NR, Moran NA. Aphid thermal tolerance is governed by a point mutation in bacterial symbionts. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(5):e96. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]