Last spring, the four of us published an essay in PNAS in which we described the severe problems now faced by scientists working in the US biomedical research system, recommending several steps that might be taken to improve the situation (1). As a follow up, we convened a two-day workshop in August that brought together 30 relatively senior individuals engaged in various aspects of biomedical science, including social scientists and others who are knowledgeable about the training pipeline.

Attendees were asked to assess two central issues: the validity of the case that we made in our article (1) and the prospects for convening a much larger and more inclusive meeting to produce a concerted plan for remedial actions. There was near unanimity among the attendees that the system is under tremendous strain, which threatens the vitality of science in the United States. To paraphrase one attendee, the root cause of the problem is the fact that the current ecosystem was designed at a time when the biomedical sciences were consistently expanding, and it now must adjust to a condition closer to steady state. Another way of stating the problem: today too many people are chasing too little money to support increasingly expensive research. It was generally conceded that without some concerted action, this problem will only get worse.

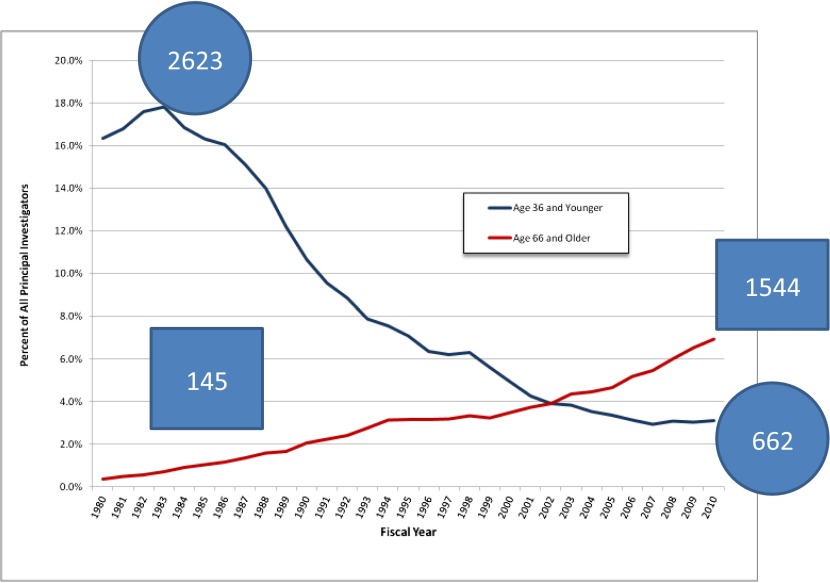

Most attendees agreed that a major consequence of the current imbalance is a hypercompetitive environment that reduces both the time available for thinking creatively and the likelihood that scientists will take risks to pursue their most imaginative ideas. Of even greater concern to the group was the dramatic change in the demographics of biomedical science, including the prolonged path to independence. Many participants were aware that the average age of first-time recipients of an NIH research grant is now about 42. However, most were surprised to learn that the percentage of NIH grant-holders with independent R01 funding who are under the age of 36 has fallen sixfold (from 18% to about 3%) over the past three decades (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of NIH R01 Principal Investigators aged 36 and younger and aged 66 and older, 1980–2010 (4).

The potential consequences of this huge demographic shift on the productivity and preeminence of American science were judged to be serious. As one participant emphasized, the United States has traditionally been viewed as the land of opportunity for young scientists, offering the most talented of them the chance to test their own ideas, raise radically new questions, and forge original paths to the answers. This feature of our system has drawn many of our most able young people to scientific careers, while simultaneously attracting outstanding young people to the United States from around the world.

The workshop also addressed the ever-increasing demands being placed upon universities, academic health centers, and research institutes as they shoulder a greater percentage of the total research budget while managing a growing number of unfunded compliance regulations. There was enthusiastic support for ongoing efforts in Washington, DC, to reduce the regulatory and compliance requirements.

Many attendees commented on the continued need to advocate for increased federal funding of research, in light of the substantial decline in spending power since the doubling of the NIH budget between 1998 and 2003. However, it was recognized that increased funding would not solve the underlying structural problems, and that major increases in funding were not likely in the near- to mid-future.

Although the participants found it difficult to agree on specific remedies to rebalance the enterprise and create a sustainable system in the future, many interesting ideas were aired that would benefit greatly from better data, more rigorous analysis, and experiments designed to test the consequences of some of the specific changes proposed.

The four authors of this report agree that the time is not yet right for the large “Asilomar-type” meeting that we originally proposed. We also understand that precipitous actions could damage a system that has served many scientists and the public well over the past several decades. However, it is equally dangerous to ignore the structural flaws that are generally acknowledged to have produced the current system. We therefore urge immediate attention to the issues raised in our April 2014 publication (1), and propose the following plan.

First, to collect essential data, develop policy recommendations, and create the momentum needed for change, a series of focused meetings should be held that build upon each other. Designed to involve diverse constituencies in many different parts of the United States, these meetings would emphasize the involvement of young scientists who represent the future, as well as minority and female scientists who are currently underrepresented in the scientific workforce. Ideally, these workshops should be convened at the grassroots level and publish their findings. An admirable model is a very large October 2014 workshop that was organized in Boston by postdoctoral trainees whose conclusions were published in a thoughtful 17-page summary (2). We are also aware of several university-based efforts in 2015, including major upcoming efforts at the University of Wisconsin, Duke University, and the University of Michigan (see, for example, https://research.wisc.edu/biomedworkforce).

Second, to help engage the major public and private United States research universities in this crucial effort, we need to connect to interested leaders from the major institutions that represent them. Such a high-level meeting with members of the American Association of Universities is already scheduled, and one university president has recently published a thoughtful essay on threats to young investigators (3). We hope to encourage many other university deans, provosts, and presidents to contribute to solutions, whether by modifying training programs, restricting growth and expenses, or attempting to reshape the research environment in which their faculty and trainees work.

Third, to help ensure that the net result of all such efforts is greater than the sum of its parts, we will be forming an “oversight group” that is composed of the four of us plus a number of others who have expressed a strong interest in working on remedies. With their guidance, we will be developing a website that organizes the relevant data and outcomes of relevant workshops and experiments.

By promoting more widespread discussion, connecting with institutional leaders, forming a larger oversight group, and communicating more effectively through a website, we aim to make sustained progress against the various logistical, administrative, and conceptual logjams that have thus far prevented the implementation of effective solutions to the major problems that many have clearly identified.

As most, if not all, of those attending the August workshop agreed, doing nothing is not an option. The stakes are enormous: the current environment is beginning to erode the remarkable opportunities created over past decades to advance our understanding of biological systems and to improve the health of the public.

Acknowledgments

We thank President Robert Tjian for hosting the August 2014 meeting at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute headquarters, and the following for their participation and contributions: Nancy Andrews (Duke University), Norman Augustine, David Baltimore (California Institute of Technology), Cori Bargmann (The Rockefeller University), Mary Beckerle (University of Utah), Jeremy Berg (University of Pittsburg), Michael Brown (University of Texas Southwestern), Jim Collins (Arizona State University), Ron Daniels (The Johns Hopkins University), Anthony Fauci (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease), Alan Garber (Harvard University), Ron Germain (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease), Joseph Goldstein (University of Texas Southwestern), Jo Handlesman (Office of Science and Technology Policy), Rush Holt (US Congress), Jay Keasling (University of California, Berkeley), Peter Kim (Stanford University), Hunter Rawlings (American Association of Universities), Joan Reede (Harvard University), Paula Stephan (Georgia State University), Larry Tabak (National Institutes of Health), Michael Teitelbaim (Harvard University), Marc Tessier-Lavigne (The Rockefeller University), Ron Vale (University of California, San Francisco), Inder Verma (The Salk Institute), Maggie Werner-Washburne (University of New Mexico), and Elias Zerhouni (Sanofi).

Footnotes

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences.

References

- 1.Alberts B, Kirschner MW, Tilghman S, Varmus H. Rescuing US biomedical research from its systemic flaws. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(16):5773–5777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404402111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDowell GS, et al. Shaping the future of research: A perspective from junior scientists. F1000Research. 2014;3:291. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.5878.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniels RJ. A generation at risk: Young investigators and the future of the biomedical workforce. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(2):313–318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418761112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NIH . Biomedical Research Workforce Working Group Report. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda: 2012. . Available at acd.od.nih.gov/biomedical_research_wgreport.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2015. [Google Scholar]