SUMMARY

We offer a theoretical model that consolidates background, environmental, and intrapersonal variables related to women’s experience of sexual coercion in dating into a coherent ecological framework and present for the first time a cognitive analysis of the processes women use to formulate responses to sexual coercion. An underlying premise for this model is that a woman’s coping response to sexual coercion by an acquaintance is mediated through cognitive processing of background and situational influences. Because women encounter this form of sexual coercion in the context of relationships and situations that they presume will follow normative expectations (e.g., about making friends, socializing and dating), it is essential to consider normative processes of learning, cognitive mediation, and coping guiding their efforts to interpret and respond to this form of personal threat. Although acts of coercion unquestionably remain the responsibility of the perpetrator, a more complete understanding of the multilevel factors shaping women’s perception of and response to threats can strengthen future inquiry and prevention efforts.

Research over the last decade has demonstrated the high prevalence of sexual violence in dating. Up to 80% of women experience some form of sexual coercion, perpetrated primarily by someone they know (Koss, 1988; Muehlenhard & Linton, 1987; Rapaport & Burkhart, 1984). Approximately 25% of women have been found to be victims of rape or attempted rape (Finkelhor & Yllo, 1985; Koss, Gidycz, & Wisniewski, 1987; Koss & Oros, 1982; Russell, 1984). Because of the high prevalence of sexual coercion perpetrated by acquaintances, preventing coercion by dating partners is receiving increased attention. Although acts of sexual coercion remain the responsibility of the perpetrator, effective individual resistance can be key to preventing victimization. Because women encounter this form of sexual coercion in the context of relationships and situations that they presume will follow normative expectations (e.g., about making friends, socializing and dating), it is essential to consider normative processes of learning, cognitive mediation, and coping that will be guiding their efforts to interpret and respond to this form of personal threat.

Many researchers have demonstrated that a woman’s active resistance dramatically decreases the likelihood of a completed rape without increasing the probability of physical injury. Although many of these researchers have focused on attacks by strangers (Griffin & Griffin, 1981, Marchbanks, Lui, & Mercy, 1990; Ullman & Knight, 1991, 1992), evidence suggests that the same physical strategies are as effective in warding off acquaintance rape as stranger rape (Levine-MacCombie & Koss, 1986; Murnen, Perot, & Byrne, 1989). However, little attention has been paid to the way that women develop responses to sexual coercion. More generally, previous researchers have not attempted to unify disparate findings from many different types of influences into a coherent theoretical structure.

The purpose of this article is twofold: (a) to offer a theoretical model that consolidates background, environmental, and intrapersonal variables related to women’s experience of sexual coercion in dating into a coherent framework and (b) to present for the first time a cognitive analysis of the process by which women formulate responses to sexual coercion. The underlying premise for this model is that a woman’s coping response to sexual coercion by an acquaintance is mediated through cognitive processing of background and situational influences. This model incorporates findings related to normative developmental learning, cognitive mediation, and coping processes in general, in addition to findings specifically related to sexual victimization by acquaintances and dating partners. In this article, we focus on women’s responses to men’s sexual coercion within heterosexual relationships. Although some of the specific variables may differ in situations of same-sex relationships or of a woman’s sexual coercion against a man, the model that we present here should generalize as an organizing framework.

The term dating refers to the continuum of courtship and relationship development from first social encounter to premarital intimate relationship. Although there is difficulty achieving consensus in defining sexual coercion, most researchers agree that sexually coercive behavior, including use of physical coercion to obtain unwanted sexual contact, rape, or attempted rape constitutes victimization (Muehlenhard, Powch, Phelps, & Giusti, 1992). However, because sexual coercion during dating often escalates, beginning with behaviors that are ambiguous as to their inappropriateness or threat, and because we are concerned here with women’s perceptions and responses in the face of unfolding degrees and forms of threat, we include a broader definition of sexual coercion as “any unwanted sexual contact–from fondling to sexual intercourse–through the use of verbal or physical pressure” (Struckman-Johnson, 1991).

It is important to note that the preponderance of research to date–and thus the work that we are drawing upon in this conceptual formulation–is largely based on samples of White, middle-class, young women. Therefore, it is as yet unclear whether or in what ways factors such as age, socioeconomic status, race, and culture may be significant factors in terms of women’s experiences, interpretations, and inclinations toward responding to sexual coercion in dating. This relative lack of attention to women’s heritage and social contexts is part of what indicates the need for a more ecological approach to study and intervention development. The cognitive appraisal processes that are posited here as serving important mediating roles would not be expected to differ as a function of factors such as race or socioeconomic status. However, the content or qualitative nature of cognitive factors such as knowledge, beliefs, and expectations and of social variables such as peer norms and patterns of socializing may well be shaped by these differences. Within an ecological framework, diversity variables are seen not only as individual status variables, but also as indicators of formal and informal social variables that need to be more vigorously investigated regarding their potential influence on women’s risk of and response to the threat of sexual coercion by a dating partner.

AN ECOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK

An approach that incorporates both background and situational variables and also provides a coherent, organizing framework that further distinguishes the multilevel influences of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and sociocultural factors is an ecological or nested ecological framework (Belsky, 1980; Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The ecological model serves as a metaphor for human interaction and human behavior (Germain & Gitterman, 1980). The principle of ecology is predicated on a view of reciprocal deterministic relations between persons and their environments and of interdependence among multiple systems in which smaller units are embedded within and influenced by larger ones. Use of the term cognitive ecological emphasizes the role of cognitive processes in governing perception and interpretation as individuals strive to establish meaning and predictability in their experiences and transactions (Brower & Nurius, 1993).

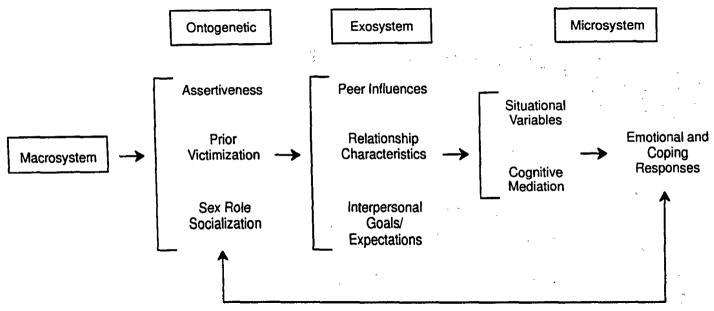

Ecological models have been previously applied to the study of violence against women (Dutton, 1988; Malamuth, Sockloskie, Koss, & Tanaka, 1991). Different levels of influence have been operationalized in terms of: (1) the macrosystem, which includes broader cultural values and belief systems, such as the messages pairing male sexual coercion with success and acceptance and the “normality” of sexual coercion (Check & Malamuth, 1985); (2) the ontogeny, or individual development factors, such as dating socialization, assertiveness, and prior experience with sexual victimization; (3) the exosystem, which includes both social units, such as peer influences and relationship variables, and interpersonal goals and expectations; and (4) the microsystem, is defined both in terms of the immediate setting within which a man and a woman interact, as well as the woman’s prevailing cognitive appraisal of that context. Although macrosystem variables may have some indirect influence on women’s recognition of and resistance to sexual coercion, their influences should be sufficiently captured through more proximal variables; thus, they will not be discussed further. While variables in Levels 1–3 “set the stage” as antecedents, variables in Level 4 are seen as those that most directly influence how risk is individually perceived and how emotional and behavioral responses are “released” in a particular situation.

Part of the utility in operationalizing an ecological framework is that it distinguishes multiple levels and forms of influence. This specification, in turn, provides theoretical guides for hypothesizing the relative effects of a potentially large set of predictor variables as well as indicating multiple levels and opportunities for prevention interventions (see Figure 1). In the remainder of this article we “walk through the model,” reviewing the identified variables that have emerged from work to date and explaining the undergirding mechanisms of influence of each system, specifically, developmental learning, cognitive mediation, and coping processes.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual Model of Women’s Responses to Male Sexual Coercion in Dating

Our greatest focus is on the microsystem variables and the processes of cognitive mediation and subsequent coping responses. We have adopted this focus because of the dearth of prior integration of these processes in the literature on sexual coercion during dating and because of their crucial role in shaping individual women’s perception and response in individual situations. The specific variables that we present are not an exhaustive list, but rather those with the greatest supportive evidence to date and ones expected to come into play with respect to cognitive appraisal processes. We recognize that there may be other relationships among the various levels of variables that are not specified. Rather, we present a conceptual model that will serve as an organizing framework for meaningfully clustering sets of variables. Likewise, we recognize that the particular responses women perform when coerced can feed back on and influence other levels of variables. Our figures do not reflect all of these potential relationships because of our reliance on published findings. To date, longitudinal studies required for specification about possible feedback loops have not yet appeared. We have, however, indicated in a general way that this sort of feedback is possible and expected.

ONTOGENETIC VARIABLES

Ontogenetic variables are the carriers of historical influences in individuals’ lives and are one conduit through which macrosystem forces exert an effect. That is, through our interactions with our environment, we receive information and develop theories about what is normative and what to expect, as well as develop personal attitudes, skills, and propensities. Although ontogenetic influences are relatively distal in relation to situation-specific responses, examination of ontogenetic variables should nevertheless provide insight into ways that this system has an impact on the formation of a woman’s detection of and resistance to sexual coercion.

Personality variables have by and large not been useful in directly predicting effective resistance to sexual coercion (Amick & Calhoun, 1987; Murnen et al., 1989). However, there is evidence that at least three background factors may have an indirect effect by being mediated through microsystem variables. The first of these is assertiveness. Although assertiveness as a global trait has not been found to contribute directly to effective resistance (Amick & Calhoun, 1987), assertive behavior at the time of the incident has been found to decrease the likelihood of a completed rape (Amick & Calhoun, 1987; Bart & O’Brien, 1985; Murnen et al., 1989). Thus, the extent to which a woman is prepared to see assertive behavior as a reasonable resistance stance and is assisted to gain assertiveness skills and habits may have an indirect effect mediated through a woman’s cognitive structures operating at the time of the coercion.

A parallel line of thought is applicable to prior victimization. Several researchers have found that a substantial number of rape victims have also been victimized earlier in life (see Browne & Finkelhor, 1986, for a review). However, a history of victimization has not always directly predicted victimization as an adult (Atkeson, Calhoun, & Morris, 1989; Mandoki & Burkhart, 1989). Mandoki and Burkhart (1989), however, did find that early victimization was related to an increased number of sexual partners later in life. This factor in turn was found to be a significant predictor of degree of adult sexual victimization. Prior victimization may have indirect effects, too, on the response to sexual coercion. Prior victimization may hamper a woman’s ability to mount an effective response, rather than allow her to draw on her previous experiences in a beneficial way.

Intuitively, one might think that a history of victimization would result in increased vigilance on a woman’s part when interacting with men. However, recent work on responses to threatening life events suggests that such events typically evoke strong short-term coping mobilization and long-term minimization responses (Taylor, 1991). In terms of victimization, this means that a woman, even when quite young, would respond to a threatening situation using all of her available coping resources. However, over time she would minimize the importance of the event. There are a variety of reasons posited for this pattern, including normative inclinations to resist negative information about self and to reestablish a sense of security to dampen the effects of past negative events. Such a pattern of minimization efforts by victims could impair their chances to translate their prior victimization experiences into effective abuse prevention and resistance that constructively builds upon this experience. Even though prior victimization is embedded in past history, i.e., it is not a characteristic of the immediate situation in which she finds herself; it can nevertheless affect the type of response she can mobilize. What is unclear at present are the specific ways in which prior victimization may influence future coping.

Female sex role socialization has also been mentioned as a factor in women’s vulnerability to sexual coercion (see Muehlenhard & Hollabaugh, 1988, and Muehlenhard & McCoy, 1991, for recent discussions). Once again, any effect of a woman’s sex role orientation on her ability to resist sexual coercion is likely to be indirect. Murnen et al. (1989) found that the trait known as hyperfemininity, a measure of sex role orientation specifically designed to assess the importance of relationships and the use of sexuality to maintain them, was not related to resistance to sexual coercion. However, a high degree of hyperfemininity was related to self-blame for being attacked. If a woman feels responsible for being coerced at the time it occurs, it follows that she would not mount as effective a resistance response than if she believed she was truly being violated. Thus, this aspect of a woman’s socialization specifically associated with dating, in conjunction with other background characteristics, could form part of a larger pattern of determinants of a woman’s resistance to sexual coercion.

Another aspect of traditional sex role socialization that could affect a woman’s response to sexual coercion is her motivation to maintain the relationship. Byers, Giles, and Price (1987) found in a role-play situation that women were less verbally definite about their refusals when they were romantically interested in their dates. Thus, if this aspect of her socialization is especially salient, a woman may not be as resistant as someone who does not value maintaining a relationship as highly.

Within the ecological framework, at least three ontogenetic variables may have some indirect influence on how a woman responds to sexual coercion. The focus here has been on factors related to a woman’s individual development. Discussion of these factors should not be interpreted as placing the onus for victimization on particular “types” of women. Rather, the intent is to give some examples of the way in which a woman’s developmental history may play some role in responding to a man’s aggressive advances. The following section emphasizes a woman’s interaction with peers and partner in determining her reactions to a sexually coercive experience.

EXOSYSTEM VARIABLES

Exosystem variables, although still considered part of one’s “background,” are more proximal influences than ontogenetic variables on the way a woman cognitively processes cues in a coercion situation and responds to them. They consist of key person and environmental factors that set the stage for this cognitive mediation. Peers and romantic partners (or potential partners) are particularly strong sources of social influence in learning appropriate social roles associated with dating. These immediate peer and partner influences (as opposed to the more dating socialization pattern discussed in the previous section) can exert a major impact on the development of one’s interpersonal goals and expectations surrounding dating. Given that these peer influences occur during the time when the risk of sexual coercion is highest, the type of norms transmitted about the content of appropriate dating roles and rituals can play a major role in a woman’s response to them. Thus, consideration of peer influences, relationship characteristics, and interpersonal goals and expectations is an important component of the larger model.

Although peer influences have not been previously considered in attempting to understand how women respond to sexual coercion, there is reason to expect that, as in so many other areas of social behavior, peers exert a major impact. A woman’s perceptions of what constitutes appropriate male sexual behavior, how to respond to men’s advances in general, and unwanted advances in particular, are likely to be affected to some extent by the types and degree of interaction a woman has had about these topics with friends. Norris (1989, 1991) has shown that both men’s and women’s sexual and affective responses to both violent and nonviolent sexual material are influenced to a great extent by information regarding peers’ responses. It is also likely that knowledge of friends’ experiences with and reactions to sexual victimization have an impact on a woman’s responses. Knowing someone who has been raped by an acquaintance or a dating partner might make a woman more aware of this possibility and thus heighten her defensiveness in social interactions (Mandoki & Burkhart, 1989).

Recent conceptualizations indicate that, rather than a one-time or an all-or-nothing phenomenon, different causes and patterns of coercion may be evident for different types of relationships. Thus, the type of relationship in which a woman is involved can affect her perception of sexually coercive cues and her responses to them. A woman might be at least somewhat wary of a man she has just met, but her level of trust increases the more deeply involved she becomes with him. Findings even indicate this sense of security may not be warranted (Lane & Gwartney-Gibbs, 1985). White (1992) found that length of time in a relationship, especially beyond five dates, is an important predictor of sexual coercion. Thus, although sexual coercion might have a high likelihood of occurring in longer-term relationships, a woman would tend to be less prepared to respond to a sexual coercion the longer she was involved. In fact, Shotland and Goodstein (1992) have shown that having had sex with someone a number of times leads individuals to believe that sex is obligated in the future. Thus, the longer a woman is in a relationship, not only is she less likely to resist unwanted sexual advances successfully (Amick & Calhoun, 1987), but evidence suggests that she actually blames herself more for the coercion than with someone she knows less well (Murnen et al., 1989). Furthermore, she is most likely to voluntarily have future contact with an assailant if she had been in an intimate relationship with him (Murnen et al., 1989).

Shotland (1992) contended that there may be as many as five varieties of dating or courtship rape. Each type arises at a different stage of a romantic relationship, these stages measured in terms of both the length of the relationship and previous sexual activity between the couple (i.e., early date rape, beginning date rape, relationship date rape, and rape within sexually active couples that does and does not include battery). Thus, it is apparent that a situational perspective that takes into account historical factors associated with the relationship holds great promise for elucidating further a woman’s cognitive appraisal of a man’s actions toward her.

A final form of exosystem variables that we address here is the interpersonal goals and expectations that the woman holds upon entering social situations and relationships. With respect to the risk of dating sexual coercion, dating-related constructs and the relationship of these constructs to women’s perception of coercion signals and perceived response options are particularly important. Dating-related constructs are influenced, although distantly, by macrosystem variables such as cultural and media messages (Linz, Wilson, & Donnerstein, 1992), personal experiences (ontogenetic variables), and personally significant social units (peers and partners). These dating-related constructs, in turn, form the basis of women’s social perceptual processes relative to dating and to dating coercion (Cantor & Zirkel, 1990; Markus & Cross, 1990; Nurius, 1991; and Showers & Cantor, 1985, provide general summaries about the cognitive mechanisms through which goals and expectations are formed and exert influence).

Both as social products and social forces, cognitive constructs such as these can be thought of both as exosystem and microsystem variables. At the exosystem level are women’s developmentally predominant goals, assumptions, and expectancies about prototypical person and situation characteristics that define dates, dating, friendship, and intimacy. At the microsystem level is the more delimited and situationally biased (e.g., by setting cues, emotional state, effects of alcohol) subset of cognitive constructs likely to be active in information processing in the encounter of coercion. Attention to women’s interpersonal goals and expectations involves recognition of developmental influences, framed in Eriksonian terms as the current life stage or, more recently, in terms of current concerns or life tasks (Cantor & Kihlstrom, 1987; Klinger, 1989). Within the context of developing friendships and romantic relationships, goals and expectations related to affiliation and intimacy are likely to be most prominent and, thus, substantial to influence the woman’s “cognitive starting point” for her transactions within social situations that serve as the forums for pursuit of these interpersonal goals.

Exosystem variables are an important part of setting the stage for subsequent microsystem variables. How peer influences, relationship factors, and individual goals and expectations merge can significantly contribute to a woman’s operating assumptions and “perceptual set” as she enters a situation she believes to be normative and affiliative but that turns out to be threatening. In the next section, we discuss how the two types of background variables–ontogenetic and exosystem–are transformed at the immediate cognitive level into a particular type of behavioral response.

MICROSYSTEM VARIABLES

Microsystem variables include both immediate situational influences on a woman’s response and the cognitive appraisal processes that she undertakes in evaluating the situation. These are considered to have the strongest impact on her behavioral and emotional responses. In this section, we discuss in detail the cognitive appraisal processes involved in determining: first, the meaningfulness of a situation and the degree of risk present, and second, the factors that affect a woman’s ability to respond. In addition, we address how particular factors, such as physical setting and alcohol consumption, can affect a woman’s responses.

Situational Factors

Several aspects of a social situation can add to the ambiguity of cues present and thus, the appraisal process that a woman undertakes in interpreting and responding to a man’s actions. Examples of such situational factors include the type of relationship between the man and the woman (Amick & Calhoun, 1987; Atkeson et al., 1989; Murnen et al., 1989); how much alcohol they have consumed (Abbey & Ross, 1992; Hawks & Welch, 1991; Muehlenhard & Linton, 1987), and the physical setting in which they socialize (Muehlenhard & Linton, 1987; Murnen, Perot, & Byrne, 1989). These situational factors have all been shown to affect the occurrence of and a woman’s response to sexual coercion. The issue of base rate needs to be taken into account in interpreting the “typicality” of factors associated with high risk of coercion; to distinguish what is typical of dates in general, versus dates on which coercion occurs. For the purposes of this paper, the focus is less on incidence and more on understanding how situational factors alone or in combination with other variables would be expected to affect a woman’s cognitive appraisal of and response to a situation–questions that have not yet been well addressed.

Amick and Calhoun (1987) found that unsuccessful resisters were more likely to be assaulted in an isolated site than successful resisters. Murnen et al. (1989) also indicated the importance of physical setting, noting that most reported incidents in their study occurred at the residence of either the assailant or the victim. Certain aspects of a setting may affect a woman’s cognitive interpretation of a man’s actions (i.e., the cues that a situation may be dangerous, and thus make her more or less likely to engage in a particular resistance response). For example, she might feel “safer” with other people around, assuming that a man would be less likely to “try something” in those circumstances. Thus, in this situation she might be less inclined to interpret the man’s behavior as coercion and to take any action to ward him off.

Major studies have demonstrated a link between alcohol consumption and the occurrence of sexual coercion by acquaintances in college populations (Koss et al., 1987; Muehlenhard & Linton, 1987). Abbey and Ross (1992) found that alcohol consumption by a woman was much more likely to be associated with completed rape than with attempted rape. Furthermore, Hawks and Welch (1991) found that women who had been drinking at the time of a rape reported less resistance on their part and less clarity of nonconsent than women who were not consuming alcohol when raped. Consistent with these findings, Norris, Nurius, Dimeff, and White (1993) found that approximately one-third of sorority women surveyed reported that alcohol consumption would be a significant barrier to making an effective response to sexual coercion. By themselves, these studies leave open the question of whether a woman is simply less able to resist coercion when drinking because of physical impairment or whether more complex cognitive processes also come into play.

Research by Norris and her colleagues has demonstrated two ways in which alcohol can affect cognitions associated with sexual coercion. First, the mere presence of alcohol can act as a cue to construct an atmosphere of sexual permissiveness, while simultaneously diminishing the gravity of sexual coercion (Norris & Cubbins, 1992; Norris & Kerr, 1993). Second, even when consuming a moderate amount, that is, not enough to debilitate one physically, alcohol appears to increase women’s acceptance of male sexual coercion. Intoxicated women have even reported a greater likelihood of enjoying victimization than did sober ones (Norris & Kerr, 1993). Thus, it is clear that alcohol is an important factor to be considered in understanding the cognitive appraisal of a sexually coercive situation.

A third set of variables that affects the cognitive formation of a resistance response concerns the characteristics of the sexual coercion itself. As defined earlier, sexual coercion can encompass a wide variety of verbal and physical behaviors, ranging from comments such as “Oh, come on, you know you like it” to outright physical force and rape. It appears from the research that the exact form of the coercion will have an impact on a woman’s response to it. For instance, Atkeson et al. (1989) found that the presence of a weapon was less likely to result in physical resistance than when no weapon was used, whereas Murnen et al. (1989) found that women resisted more strongly as the assailant’s means of attack escalated.

Although helpful in demonstrating the link between specific coercion characteristics and resistance, these researches did not address how a woman’s interpretation of particular actions by the man develops and results in a resistance response. The role of interpretation is particularly important to acquaintance sexual coercion because this form of coercion often does not involve the use of an unmistakable cue such as a deadly weapon. For instance, if, after a couple has engaged in some amount of mutually consensual sexual behavior, the man slowly escalates his verbal or physical demands for further sexual interaction, then whether the man is engaging in sexual coercion can be ambiguous. It might take repeated refusals on the part of the woman before she decides that the man’s behavior is inappropriate, especially if her cognitive processes are further affected by alcohol consumption. At the other extreme, if a man almost immediately attacks a woman physically, the cognitive processing of her defensive response would probably be quite rapid and strong.

Cognitive Appraisal Factors

A major difference affecting the ability to resist coercion by strangers versus acquaintances lies in the cognitive appraisal processes that a woman must undertake before she engages in a behavioral response. Recognizing danger cues in a social context requires much more complex psychological processing than does recognition of such cues in a stranger attack (Amick & Calhoun, 1987). To identify how cognitive appraisal variables affect women’s perception of danger cues and responses to them, the recent social cognitive literature related to threatening life events is particularly informative. A considerable amount of work in this area has focused on adaptation and coping in the aftermath of negative events. However, recent analyses of appraisal processes as situations turn from neutral or positive to threatening provide important advances in our understanding of the cognitive challenges and tasks that a woman must undertake and ways by which her situational appraisals influence emotional and behavioral responding.

In this work, appraisals are defined as evaluations of what one’s relationship to the environment implies for personal well-being. The first set, referred to as primary appraisals, has to do with searching for meaning in the event. This takes an initial form in appraisal of whether a phenomenon or event is self-relevant and whether it is neutral, poses benefit, or poses threat (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). With respect to sexual coercion in dating, this involves the woman appraising that some aspect of the setting or the man’s behavior is incongruent with her affiliation and safety goals, as well as an accurate assessment of whether the situation is potentially dangerous to her. Because recognizing danger cues is the first step in mounting an effective defense (Rozée, Bateman, & Gilmore, 1991), understanding the elements that lead a woman to interpret a social situation as threatening is crucial.

When the threat takes form suddenly and severely, primary appraisals are relatively straightforward. These appraisals can be complicated, however, by several aspects of the situation and social interaction, some of which were discussed previously. An additional element influencing women’s cognitive mediation of cues related to sexual coercion by acquaintances involves influences of “working knowledge.” At any one point in time, only a limited amount of our total repertoire of knowledge, beliefs, and capabilities can be active in awareness or working memory (Anderson, 1983). Those cognitive structures that are currently active will have their greatest influence on information processing in the moment. Factors that influence what gets activated include the goals and expectations that were prominent upon entering the situation, as well as the individual’s mood and the setting cues (Browne & Taylor, 1986; Fiske & Taylor, 1991). Thus, one cognitive challenge for women arises at this early stage of detecting threat–a safety-related search and appraisal task that is likely to be discrepant with the social scenario of fun and friendship and with her affiliation-oriented goals, expectancies, mood, and situational interpretations.

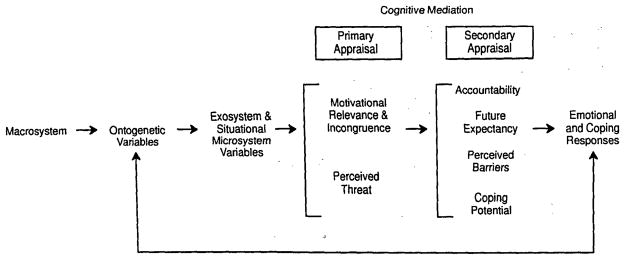

The second type of cognitive appraisal, referred to as secondary appraisals, centers more around determinations of coping resources, options, and outcomes. The amount and type of coping or mastery potential a woman believes herself to have in the moment will in part determine the specific response she actually draws on from the total repertoire possible. If the event is judged to pose a personal threat, a number of subsequent interpretations are needed: (a) what is the nature of this threat? (b) who is at fault or accountable? (c) what are my coping options or resources? (d) how well can I draw upon these options or resources? (e) what barriers do I face in enacting these options? and (f) what are the possibilities of change in the situation that could make it more or less threatening? (Smith & Lazarus, 1990, 1993; Smith, Haynes, Lazarus, & Pope, 1993). Figure 2 displays the function of these primary and secondary appraisal processes in cognitively mediating the effects of background and contextual variables.

FIGURE 2.

Primary and Secondary Appraisal Processes Mediating Emotional and Coping Responses to Sexual Coercion

Again, these appraisals are more straightforward when the situation is more clear-cut. In sexual coercion during dating, there are different types of threat or loss that the woman may have to simultaneously weigh, constituting a kind of multivariate cost-benefit analysis involving potentially conflicting goals and concerns: personal safety related to sexual victimization (e.g., “If I give in, maybe he won’t hurt me”), personal safety related to resistance efforts (e.g., “He might just get angrier if I resist”), social costs associated with drawing the attention of others to what she may see as a stigmatizing event (e.g., “Maybe they’ll think I led him on”), and concerns related to damaging her relationship with the male (e.g., “What if I’m wrong about his intentions and he is insulted?”). Thus, women encounter another form of cognitive challenge in needing to undertake secondary appraisals under conditions of the potentially disruptive effects of confusion, competing concerns, and high emotionality. Findings from a recent study of sorority women’s expectations about the feelings and concerns they would have in encountering sexual coercion during dating, and how these thoughts and feelings would influence their behavioral responses reflected this kind of cognitive challenge (Nurius, Norris, & Dimeff, 1995). The psychological barriers to responding effectively to sexual coercion most strongly endorsed by these women concerned being viewed as “loose,” getting a reputation as a “tease,” and fear of embarrassment (Norris et al., 1993).

The importance of emotional responses is their role in mobilizing the person to cope and in biasing the directions of this coping effort. Emotion has a powerful influence in information processing–what gets searched for, noticed, recalled, and decided tends to be mood-congruent–at times interfering with cognitive activity and coping (e.g., Schwarzer, 1984). Recent analysis also indicates that emotions are cognitively represented in memory and that different emotions tend to be associated with information about different modes of responding. Thus, different emotions predispose individuals to certain forms of action readiness (Frijda, 1987; Frijda, Kuipers, & ter Schure, 1989). Specific cognitions, such as evaluations about circumstances, have been found to be strongly related to specific emotions. Anger has been associated with blaming someone for an unwanted situation, guilt with blaming oneself, fear with thinking that one is endangered, and hurt or sadness with perceived betrayal or loss (see Folkman & Lazarus, 1988; Lazarus & Smith, 1988; Smith et al., 1993; and Smith & Lazarus, 1993, for reviews).

Thus, women’s emotional responses experienced at the time of a sexual coercive experience are closely intertwined with her behavioral responses. For example, experiencing anger and its concomitant appraisal that the assailant is indeed responsible for the situation is likely to result in assertive and situationally-focused coping responses (Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, 1986). On the other hand, a woman whose predominant cognitive and emotional set involves guilt (e.g., “This is awful. I must have given him the wrong impression; otherwise, he would not be acting this way.”) is more likely to try to appease her date while also trying to set limits, resulting in mixed messages and less physically assertive resistance responses. Although it is by no means impossible to access cognitive structures associated with perpetrator accountability and skills associated with physical resistance under the latter conditions, their incongruence with the prevailing feelings of guilt will be an impediment to such interpretations and behavioral responses.

One factor that complicates the appraisals that women make about a situation is a set of cognitive biases manifested by unrealistic optimism, exaggerated perceptions of mastery, and overly positive self-evaluations. Typically, this normative “illusory glow” is associated with positive mental health and social functioning, as well as with successful coping and reestablishing psychological well-being in the aftermath of threat (Friedland, Keinan, & Regev, 1992; Greenwald, 1980; Scheier & Carver, 1985; Taylor, 1989; Taylor & Brown, 1988). However, these cognitive predispositions may serve to exacerbate women’s risk with respect to sexual coercion in dating. For example, although traditional sexual scripts may incline women to expect sexual pressure from men and adversarial interactions related to refusal of men’s advances, positivity bias would incline women on an individual basis to believe that this would remain in manageable limits, that the men they know would be unlikely to “cross the line,” and that they could handle the situation. In short, the double-edged sword here is biasing effect on women of underestimating their own likelihood of encountering sexual coercion in spite of having knowledge of the risks for women in general (Norris et al., 1993); of overlooking or misinterpreting coercion cues (Rozée et al., 1991); and of overestimating their efficacy in effectively resisting sexual coercion (Murnen et al., 1989).

Because of its widespread and generally health-promoting effects, this positivity bias is a particularly difficult phenomenon to address. Its presence suggests that education about risk is insufficient for effective sexual coercion resistance and prevention intervention and that greater understanding of the dynamics to women’s appraisal processes related to risk and protection is needed. Findings about the cognitive appraisal variables reviewed here suggest the need to build upon prior educational efforts to include attention to such factors as: difficulties in making the step from intellectual recognition of the social problem of sexual coercion in dating to recognition of the personal relevance of this problem and risk; impediments to early detection of threat (e.g., to searching for and interpreting threat cues from dating partners); the conflicts and cost-benefit dilemmas that may serve as impediments to rapid and decisive response; ways in which resistance actions may be affected by microsystem, exosystem, and ontogenetic variables; and the need for anticipatory coping, for cognitive and behavioral rehearsal and for involvement of supportive others such as peers.

At the microsystem level, at least three categories of immediate context variables–the physical setting, alcohol consumption, and the characteristics of the coercion–could all influence a woman’s cognitive interpretation of a man’s actions and her behavioral response to him. The ways that these variables affect her behavior are mediated through the cognitive processes discussed previously. These cognitive processes are the mechanisms by which women appraise dating events for their risk to her. It is apparent that cognitive appraisals serve the important mediational role of linking prior goals and beliefs with situational cognitive interpretations and subsequent behavioral and emotional responses (cf. Nurius, Furrey, & Berliner, 1993, in relation to abusive partners.) These contextual variables and cognitive appraisal processes, because of their situational immediacy, are believed to have the strongest impact on a resistance response. However, there is reason to believe that more distal variables–macrosystem, ontogenetic, exosystem–also affect, at least indirectly, a woman’s ability to resist sexual coercion.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Although different researchers have identified factors associated with women’s resistance to sexual coercion, no one has previously presented a model integrating several levels of variables that can determine such a response. We have shown here that an analysis of women’s cognitive appraisals at the time of a sexual coercion may be a useful approach to understanding how women appraise the risk of being sexually coerced and formulate a response based on that risk. Furthermore, we have identified a number of background variables in the form of the individual’s ontogeny, or individual development and history, and the exosystem, or social influences and individual goals and expectations related to the specific situation, that can affect a woman’s resistance, albeit indirectly. We have presented evidence to support the various components of the model. However, it remains for future researchers to test this model in part or entirety and determine the strength of its causal links.

The importance of assessing these categories of variables is their bearing on understanding the corresponding contextual and interpretive frameworks within which women appraise and respond to threat by a partner. This model will guide future researchers who extend beyond college populations and who, ultimately, guide development of prevention strategies tailored to the needs of women with differing backgrounds exposed to differing forms and severity of coercion. As noted earlier, inquiry into acquaintance sexual coercion has not yet done full justice to the diversity of women, their life experiences, or their environments. Given that age, socioeconomic status, and race have been found to be significant distinguishing factors in patterns of dating and marital aggression (Day, 1992; Hotaling & Sugarman, 1986; Sugarman & Hotaling, 1989), these factors constitute important deficits in research to date. Future researches should make a special effort to include greater diversity with respect to these characteristics.

It is important to emphasize that teaching women to detect and respond to sexual coercion does not place the onus for its occurrence on them. The act is still the responsibility of the perpetrator. But it is necessary to acknowledge that, for the foreseeable future, there will be sexually coercive men in this society and that women can empower themselves by preparing to recognize and cope with high-risk situations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Irene Hanson Frieze and Thomas Graham for their helpful input on earlier versions of this article.

Footnotes

[Haworth co-indexing entry note]: “A Cognitive Ecological Model of Women’s Response to Male Sexual Coercion in Dating.” Nurius, Paula S., and Jeanette Norris. Co-published simultaneously in Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality (The Haworth Press, Inc.) Vol. 8, No. 1/2, 1996, pp. 117–139; and: Sexual Coercion in Dating Relationships (ed: E. Sandra Byers, and Lucia F. O’Sullivan) The Haworth Press, Inc., 1996, pp. 117–139. Single or multiple copies of this article are available from The Haworth Document Delivery Service [1-800-342-9678, 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. (EST)].

References

- Abbey A, Ross LT. The role of alcohol in understanding misperception and sexual assault. Paper presented at the 100th annual meeting of the American Psychological Association; August.1992. [Google Scholar]

- Amick EA, Calhoun KS. Resistance to sexual aggression: Personality, attitudinal, and situational factors. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1987;16:153–163. doi: 10.1007/BF01542068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JR. The architecture of cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Atkeson BM, Calhoun KS, Morris KT. Victim resistance to rape: The relationship of previous victimization, demographics, and situational factors. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1989;18:497–507. doi: 10.1007/BF01541675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bart PB, O’Brien PH. Stopping rape: Successful survival strategies. Elmsford: Pergamon; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Child maltreatment: An ecological integration. American Psychologist. 1980;35:320–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.35.4.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brower A, Nurius PS. Social cognition and individual change: Current theory and counseling guidelines. New York: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Browne JD, Taylor SE. Affect and processing of personal information: Evidence for mood-activated self-schemata. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1986;22:436–452. [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Finkelhor D. Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99:66–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers ES, Giles BL, Price DL. Definiteness and effectiveness of women’s responses to unwanted sexual advances: A laboratory investigation. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1987;8:321–338. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor N, Kihlstrom JF. Personality and social intelligence. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor N, Zirkel S. Personality, cognition, and purposive behavior. In: Pervin LA, editor. Handbook of personality theory and research. New York: Guilford; 1990. pp. 135–164. [Google Scholar]

- Check JVP, Malamuth N. An empirical assessment of some feminist hypotheses about rape. International Journal of Women’s Studies. 1985;8:414–423. [Google Scholar]

- Day RD. The transition to first intercourse among racially and culturally diverse youth. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:749–762. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton DG. The domestic assault of women: Psychological and criminal justice perspectives. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Yllo K. License to rape. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Taylor SE. Social cognition. 2. New York: McGraw Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Coping as mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:466–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen R. The dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:992–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland N, Keinan G, Regev Y. Controlling the uncontrollable: Effects of stress on illusory perceptions of controllability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:923–931. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.6.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frijda NH. Emotion, cognitive structure, and action tendency. Cognition and Emotion. 1987;1:115–143. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda NH, Kuipers P, ter Schure E. Relations among emotion, appraisal, and emotional action readiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:212–228. [Google Scholar]

- Germain CB, Gitterman A, editors. The life model of social work practice. New York: Columbia University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG. The totalitarian ego: Fabrication and revision of personal history. American Psychologist. 1980;35:603–618. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin BS, Griffin CT. Victims in rape confrontation. Victimology: An International Journal. 1981;6:59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hawks BK, Welch CD. Alcohol and the experience of rape. Paper presented at the annual meetings of the American Psychological Association; August; San Francisco. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hotaling GT, Sugarman DB. An analysis of risk markers in husband to wife violence: The current state of knowledge. Violence & Victims. 1986;1:101–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinger E. Goal orientation as psychological linchpin: A commentary on Cantor and Kihlstrom’s “Social intelligence and cognitive assessments of personality”. In: Wyer RS, Srull TK, editors. Advances in social cognition. Vol. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1989. pp. 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP. Hidden rape: Sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of students in higher education. In: Burgess AW, editor. Sexual assault. II. New York: Garland; 1988. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CJ, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. The sexual experiences survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:455–457. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane KA, Gwartney-Gibbs PA. Violence in the context of dating and sex. Journal of Family Issues. 1985;6:45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R, Smith CA. Knowledge and appraisal in the cognition-emotion relationship. Cognition and Emotion. 1988;2:281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Levine-MacCombie J, Koss MP. Acquaintance rape: Effective avoidance strategies. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1986;10:311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Linz D, Wilson BJ, Donnerstein E. Sexual violence in the mass media: Legal solutions, warnings, and mitigation through education. Journal of Social Issues. 1992;48:145–171. [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Sockloskie RJ, Koss MP, Tanaka JS. Characteristics of aggressors against women: Testing a model using a national sample of college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:670–681. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandoki CA, Burkhart BR. Sexual victimization: Is there a vicious cycle? Violence and Victims. 1989;3:179–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchbanks PA, Lui K-J, Mercy JA. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1990;132:540–549. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Cross S. The interpersonal self. In: Pervin LA, editor. Handbook of personality theory and research. New York: Guilford; 1990. pp. 576–598. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenhard CL, Hollabaugh LC. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:872–879. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenhard CL, Linton MA. Date rape and sexual aggression in dating situations: Incidence and risk factors. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1987;34:186–196. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenhard CL, McCoy ML. Double standard/double bind: The sexual double standard and women’s communication about sex. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1991;15:447–461. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenhard CL, Powch IG, Phelps JL, Giusti LM. Definitions of rape: Scientific and political implications. Journal of Social Issues. 1992;48:23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Murnen SK, Perot A, Byrne D. Coping with unwanted sexual activity: Normative responses, situational determinants, and individual differences. The Journal of Sex Research. 1989;26:85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Norris J. Social influence effects on responses to sexually explicit material containing violence. The Journal of Sex Research. 1991;28:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Norris J. Normative influence effects on sexual arousal to nonviolent sexually explicit material. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1989;19:341–352. [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Cubbins LA. Dating, drinking, and rape: Effects of victim’s and assailant’s alcohol consumption on judgments of their behavior and traits. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1992;16:179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Kerr KL. Alcohol and violent pornography: Responses to permissive and nonpermissive cues. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993 doi: 10.15288/jsas.1993.s11.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Nurius PS, Dimeff LA, White R. Gender comparisons and the experience of rape. Paper presented at a meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Sex; Western Region, Seattle WA. 1993. Apr 16, [Google Scholar]

- Nurius PS. Possible selves and social support: Social cognitive resources for coping and striving. In: Howard J, Callero P, editors. The self-society dynamic. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nurius PS, Furrey J, Berliner L. Coping capacity among women with abusive partners. Violence and Victims. 1993;7(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurius PS, Norris J, Dimeff LA. Through her eyes: Cognitive challenges for women in perceiving acquaintance rape threat. 1995. Manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport K, Burkhart BR. Personality and attitudinal characteristics of sexually coercive college males. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1984;93:216–221. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royce PD, Bateman P, Gilmore T. The personal perspective of acquaintance rape prevention: A three-tier approach. In: Parrot A, Beckhofer L, editors. Acquaintance rape: The hidden crime. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1991. pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rozée PD, Bateman P, Gilmore T. The personal perspective of acquaintance rape prevention: A three-tier approach. In: Parrot A, Beckhofer L, editors. Acquaintance rape: The hidden crime. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1991. pp. 337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Russell DEH. Sexual exploitation: Rape, child sexual abuse, and workplace harassment. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, editor. The self in anxiety, stress, and depression. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Shotland RL. A theory of the causes of courtship rape: Part 2. Journal of Social Issues. 1992;48:127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Shotland RL, Goodstein L. Sexual precedence reduces the perceived legitimacy of sexual refusal: An examination of attributions concerning date rape and consensual sex. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18:756–764. [Google Scholar]

- Showers C, Cantor N. Social Cognitives: A look at motivated strategies. Annual Review of Psychology. 1985;36:275–305. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Lazarus RS. Appraisal components, core relational themes, and the emotions. Cognition and Emotion. 1993;7:233–269. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Lazarus RS. Emotion and adaptation. In: Pervin LA, editor. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Haynes KN, Lazarus RS, Pope LK. In search of the “hot” cognitions: Attributions, appraisals, and their relation to emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:916–929. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.5.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struckman-Johnson C. Male victims of acquaintance rape. In: Parrot A, Bechhofer L, editors. Acquaintance rape: The hidden crime. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1991. pp. 192–214. [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman DB, Hotaling GT. Dating violence: Prevalence, context and risk markers. In: Pirog-Good MA, Stets JE, editors. Violence in dating relationships: Emerging social issues. New York: Praeger; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:193–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE. Asymmetrical effects of positive and negative events: The mobilization-minimization hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:67–85. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE. Positive illusions: Creative self-deception and the healthy mind. New York: Basic Books; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Knight RA. A multivariate model for predicting rape and physical injury outcomes during sexual assaults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:724–731. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Knight RA. Fighting back: Women’s resistance to rape. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1992;7:31–43. [Google Scholar]

- White J. Personal communication. Nov, 1992.