Abstract

Purpose

Attachment theory can provide a heuristic model for examining factors that may influence the relationship of social context to adjustment in chronic pain. This study examined the associations of attachment style with self-reported pain behavior, pain intensity, disability, depression and perceived spouse responses to pain behavior. Further, we examined whether attachment style moderates associations between perceived spouse responses and self-reported pain behavior and depressive symptoms. We also explored perceived spouse responses as a mediator of these associations.

Method

Individuals with chronic pain (N=182) completed measures of self-reported attachment style, perceived spouse responses, and pain-related criterion variables.

Results

Secure attachment was inversely associated with self-reported pain behaviors, pain intensity, disability, depressive symptoms and perceived negative spouse responses; preoccupied and fearful attachment scores were positively associated with these variables. In multivariable regression models, both attachment style and perceived spouse responses were uniquely associated with self-reported pain behavior and depressive symptoms. Attachment style did not moderate associations between perceived spouse responses to self-reported pain behavior and pain criterion variables, but negative spouse responses partially mediated some relationships between attachment styles and pain outcomes.

Conclusions/Implications

Findings suggest that attachment style is associated with pain-related outcomes and perceptions of significant other responses. While the hypothesized moderation effects for attachment were not found, mediation analyses showed that perceived spouse responses may partially explain associations between attachment and adjustment to pain. Future research is needed to clarify how attachment style and the social environment affect the pain experience.

Keywords: chronic pain, attachment, spouse responses, pain behavior, depression

Introduction

Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1980, 1982; Romano et al., 1995) provides an important heuristic model for the study of psychological and social development. It posits that the quality and nature of interactions between a child and primary caregiver lead to internalized working models of self and others with implications for emotion regulation, coping with threats to well-being, and social and psychological adjustment throughout the lifespan. Attachment processes are theorized to be activated by perceived threats to security or well-being. Adult attachment research has extended these concepts to the study of adult functioning, including coping with pain (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

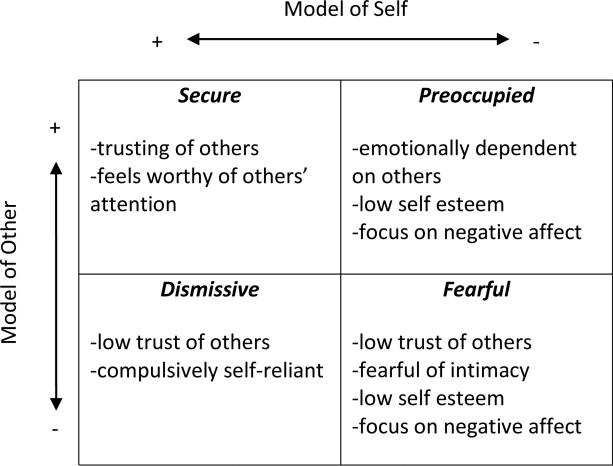

Adult attachment has been conceptualized both (1) as a continuous phenomenon defined by dimensions of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance (Kurdek, 2002) and (2) as a categorical variable in which individuals can be classified into one of three or four different primary attachment types (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991a; Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994a). Based on an extensive review of the literature on the use of adult attachment measures over a 25-year span, Ravitz et al (Ravitz, Maunder, Hunter, Sthankiya, & Lancee, 2010) concluded that it remains unclear as to whether attachment phenomena are inherently categorical or dimensional. Both categorical and dimensional approaches to the assessment of attachment continue to be represented in the literature (Ravitz et al., 2010). One influential model in the adult attachment literature has posited orthogonal dimensions of positive and negative models of self and others (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991a; Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994b), leading to a typology of attachment styles as illustrated by the four quadrants in Figure 1. Secure attachment is characterized by positive models of both self and others, while insecure attachment styles are marked by negative models of self and/or others. Specifically, a preoccupied style is defined by a positive model of others but a negative model of self, a dismissive style by positive models of self but negative of others, and a fearful style by negative models of both self and others (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991a; Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994b).

Figure 1.

Attachment styles and models of the self and other. Figure adapted from Bartholomew and Horowitz (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991a), modifications by Ciechanowski et al. (Ciechanowski et al., 2003)

The Attachment-Diathesis Model of Chronic Pain (ADMPC; Meredith, Ownsworth, & Strong, 2008) provides a framework for how insecure attachment may confer vulnerability for poor outcomes in chronic pain, particularly in the context of maladaptive cognitive appraisals such as perceptions of low self-efficacy. Given that pain is aversive and may present a threat to well-being, attachment processes could theoretically be activated by the experience of pain and influence individuals’ response to pain. Consistent with this model, empirical studies have shown that insecure attachment is associated with chronic widespread pain (Davies, Macfarlane, McBeth, Morriss, & Dickens, 2009), higher levels of pain-related fear and hypervigilance (McWilliams & Asmundson, 2007), higher levels of emotional distress and catastrophizing (Ciechanowski, Sullivan, Jensen, Romano, & Summers, 2003; McWilliams & Asmundson, 2007; McWilliams & Holmberg, 2010), and lower self-efficacy for coping with pain (Meredith, Strong, & Feeney, 2006), particularly for those with negative models of the self. Attachment styles may also influence the extent to which individuals seek support at times of threat or stress and perceive others as available to provide support. Consistent with this idea, individuals with low levels of attachment anxiety and higher comfort with closeness have reported more support and satisfaction with support from others in their social environments and to engage in more support-seeking behavior (Meredith et al., 2008).

While attachment processes as a factor in chronic pain adjustment have been the subject of recent study, the social context of chronic pain has also long been considered as influential in adaptation to chronic pain (Romano, Cano, & Schmaling, 2011). Fordyce (Fordyce, 1976) first conceptualized the social context in a behavioral framework which posits that social responses in the environment of persons with chronic pain may reinforce pain behaviors. Studies have found that patient-reported (Flor, Kerns, & Turk, 1987; Flor et al., 1989; Kerns et al., 1991; Stroud, Turner, Jensen, & Cardenas, 2006) and observed (Romano et al., 1991; Romano, Jensen, Turner, Good, & Hops, 2000) solicitous responses of spouses are associated with higher levels of patient pain behaviors and poorer function. Negative spouse responses have been less consistently associated with functioning and more consistently associated with lower patient mood and poorer psychological adjustment (Cano, Gillis, Heinz, Geisser, & Foran, 2004; Cano, Weisberg, & Gallagher, 2000; Kerns, Haythornthwaite, Southwick, & Giller, 1990; Schwartz, Slater, & Birchler, 1996; Turk, Kerns, & Rosenburg, 1992). Variables such as relationship satisfaction, depression, or gender have been found in some studies to moderate the association between spouse responses and patient outcomes (e.g., Fillingim, Doleys, Edwards, & Lowery, 2003), although results across studies on the role of these moderating variables have not been consistent (see Romano et al., 2011 for review).

In spite of the importance of both attachment processes and the social context for adaptation to pain, the role that attachment styles and spouse responses and their potential interactions on pain-related outcomes remain unexplored. Attachment style represents another potential moderator of the relationship between social responses of spouses and adjustment to chronic pain. As discussed previously, attachment style is posited to represent an enduring tendency formed early in life; it is therefore likely to predate the onset of chronic pain. Attachment models might suggest that an insecure attachment style marked by negative models of the self (fearful and preoccupied attachment styles) may be associated not only with higher levels of distress, pain, and catastrophizing as cited above, but might also be associated with a stronger relationship between solicitous spouse responses and pain behaviors, given the association between such attachment styles and reported lower self-efficacy for coping with pain (Meredith et al., 2006). If persons with chronic pain see themselves as unable to cope on their own with pain, they may more predisposed than those with higher pain self-efficacy to find solicitous responses by others as reinforcing. Attachment theory would also suggest that preoccupied and fearful attachment styles may be associated with a stronger relationship between negative spouse responses and low mood, given the documented association of such attachment styles with higher levels of emotional distress and catastrophizing (Ciechanowski et al., 2003; McWilliams & Asmundson, 2007; McWilliams & Holmberg, 2010).

The ADMCP also notes that factors such as appraisals, including appraisals of social support, may mediate the effects of attachment on pain outcomes (Meredith et al., 2008). Extending this reasoning, perceptions of social responses to pain behaviors may potentially mediate associations found between attachment styles and pain outcomes, which could provide an alternative pathway by which both attachment and social responses play a role in patient adjustment and functioning. In addition, given the importance of developing more effective treatments for individuals with chronic pain and the significant role that psychosocial factors play in adjustment and functioning, understanding how attachment styles may be related to factors maintaining pain behaviors and disability has the potential, if confirmed in future research, to inform treatment development efforts and tailoring of treatments to individual needs.

The overarching goal of this study was to examine the complex associations between adult attachment styles, spouse responses, and pain outcomes in a sample of individuals with chronic pain. To address this goal, this study (1) examined relationships between attachment style and (a) self-reported pain behavior, pain intensity, disability and depressive symptoms, and (b) perceived spouse responses to patient pain behavior; (2) tested whether attachment style moderates associations between perceived spouse responses and self-reported pain behavior and depression; and (3) tested whether spouse responses mediate any associations found between attachment styles and self-reported pain behavior and depression. We hypothesized, based on attachment theory as well as evidence from prior studies, that there would be a significant relationship between preoccupied and fearful attachment styles and higher levels of pain, pain behavior, disability and depressive symptoms. We also hypothesized that preoccupied and fearful attachment styles would moderate the association between perceptions of spouse responses and self-reported pain behavior and depression. Further, we explored whether perceptions of spouse responses mediate any significant associations between attachment style and self-reported pain behavior and depression.

Procedures

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Alabama and the University of Washington. A heterogeneous sample of persons with chronic pain was recruited through multiple methods, described below. Recruitment was conducted at multiple sites in order to increase the diversity of our sample in terms of pain conditions and severity and other sociodemographic factors. Eligible participants were individuals with chronic pain (defined by at least 3 pain days per month for 3 months or longer), who were married or living with a romantic partner who was also willing to participate (all partners in the current study are referred to as “spouse” regardless of actual marital status). Although the current study presents data from persons with pain only, both the person with pain and their spouse were required to participate because partner data is required for planned future projects. Participants and their spouses were asked to complete an assessment packet without discussing their responses. Completion of questionnaires took approximately 45 minutes. Each couple received $30 ($15 per person) for completion of the assessment packet.

Persons with chronic headache or musculoskeletal pain (e.g., low back pain, pain in the neck, knees or other joints, arthritis, fibromyalgia) were recruited from 3 different medical centers: the Kilgo Headache Clinic (a specialty clinic in Tuscaloosa, Alabama), the Internal Medicine Clinic at the University Medical Center (a general internal medicine clinic in Tuscaloosa, Alabama), and the Pain and Rehabilitation Institute (a multidisciplinary specialty pain clinic in Birmingham, Alabama). At each clinic, on days when the study investigator was present, the nursing staff provided consecutive patients with a description of the study and those who were interested met with the investigator following his/her appointment. Fliers with response cards were also posted in the waiting rooms. Interested patients met in person with the investigator at the clinic to determine eligibility and receive the necessary materials. Assessment packets were completed at home and returned by mail in a preaddressed, stamped envelope. Participants received 2 reminder phone calls (1 week and 1 month after entrance into the study). To increase compliance with the request to complete packets independently, participants were required to confirm, in writing, a statement declaring that he/she completed his/her assessment independently. A total of 280 couples were enrolled at these sites and 158 couples completed the questionnaires (return rate of 56%).

Persons with musculoskeletal pain were also recruited through a series of advertisements run in the Tuscaloosa News, a local daily newspaper. Five couples responding to the advertisement were brought into the laboratory to meet the investigator and determine eligibility. Participants and their spouses completed the assessments in separate rooms in the laboratory.

Finally, persons with a history of amputation were recruited as part of a series of survey studies through the University of Washington designed to examine pain (amputation-related or not) in persons with disabilities. Specifically, research staff contacted potential participants via telephone who (1) had completed a previous survey about quality of life in persons with an acquired amputation, (2) indicated that they experienced pain when completing the initial survey, (3) indicated that they were willing to be contacted about future research opportunities, and (4) indicated that they were married or living with a significant other at the time the initial survey was completed. Research staff mailed informed consent forms and copies of the study survey to all participants who met these eligibility criteria (N = 70) and stated that they were interested in participating. Of these, 49 participants returned completed surveys (return rate of 70.0%). However, only 43 of these reported that they continued to experience pain and were eligible for this study.

Participants

A total of 206 eligible persons with chronic pain returned a packet of questionnaires. Analyses were limited to those with complete data (N=182) on perceived spouse responses, attachment style, and pain criterion variables (pain intensity, pain behavior, disability, depressive symptoms). The study sample was recruited as follows: 142 (78%) were recruited from the clinics in Alabama, 4 (2%) through newspaper advertisements in Alabama, and 36 (20%) from the University of Washington survey studies. The study sample did not differ from those excluded due to missing data on sex, marital status, relationship duration, or number of pain conditions. However, the study sample was significantly younger (t=2.97, p=0.003) and tended toward shorter pain duration (t=1.97, p =0.06) compared to those excluded due to missing data.

Participants with headache or musculoskeletal pain were different from those with pain and a history of amputation in a number of ways. Participants with musculoskeletal pain were significantly younger (t= -6.41, p <0.001), and reported shorter length of marriage/cohabitation (t=-3.41, p=0.001), shorter pain duration (t= -2.25, p <0.05), higher perceived solicitous responses to pain behavior (t=1.96, p=0.05), higher perceived negative responses to pain behavior (t=2.23, p<0.05), higher pain behavior (t=3.42, p=0.001), higher pain intensity (t=5.00, p<0.001), higher depressive symptoms (t=5.89, p<0.001), and lower secure attachment (t=-2.98, p<0.01). Participants with musculoskeletal pain were also more likely to be female (χ2=25.31, p<0.001). There were no differences based on pain source on fearful attachment, preoccupied attachment, dismissive attachment, or disability (all p>0.05).

Measures

Demographics

Participants provided basic demographic information, as well as information on chronic pain history and amputation history (where relevant).

Attachment

Attachment style was operationalized by continuous index scores for each of four attachment styles. Index scores were computed from scores on the Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ) (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994a, 1994b) and the Relationship Questionnaire (RQ) (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991a) as described below.

The RSQ is based on common descriptors of attachment style based on conceptualizations of secure and insecure attachment patterns (Collins & Read, 1990; Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994a, 1994b; Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Simpson, Rholes, & Nelligan, 1992). Participants indicate the extent to which each of 17 statements describes their style in close relationships (e.g., “I find it easy to get emotionally close to others,” “I find it difficult to trust others completely”). Responses are given on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Not at all like me”) to 5 (“Very much like me”). The RSQ provides continuous subscale scores related to four styles of attachment by taking the mean of relevant items: secure (5 items), fearful (4 items), preoccupied (4 items), and dismissing (5 items). The RSQ subscales have demonstrated adequate convergent validity with interview assessments and moderate stability in attachment over 8 months (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994a). The four RSQ subscales have demonstrated low to moderate internal consistency (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994b), including in chronic pain populations (Ciechanowski et al., 2003).

The RQ is comprised of 4 short paragraphs, each describing an attachment pattern (secure, fearful, preoccupied, dismissing) in close adult peer relationships. For example, the item related to secure attachment reads “It is easy for me to become emotionally close to others. I am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don't worry about being alone or having others not accept me.” Participants rate the extent to which each statement describes their style on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Not at all like me”) to 7 (“Very much like me”). Ratings of the four attachment styles based on the RQ have shown adequate convergent validity with interview assessments (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994a) and moderate stability over an 8 month period (Scharfe & Bartholomew, 1994) and convergence with structured interviews of attachment style (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991b).

As noted by Ravitz et al. (2010), the internal consistencies of the RQ and RSQ have varied widely as reported in the literature. To increase the internal consistency of attachment style scores using these measures, an index of the RSQ and RQ was formed (Ognibene & Collins, 1998) that has been used in multiple studies of persons with other chronic illnesses (Ciechanowski, Katon, Russo, & Walker, 2001; Pegman, Beesley, Holcombe, Mendick, & Salmon, 2011) or in health-related settings (Ahrens, Ciechanowski, & Katon, 2012). First, each RSQ subscale score and RQ item rating was standardized (i.e., transformed such that the sample mean was 0 and the sample standard deviation was 1 using the following formula: [individual mean – sample mean]/sample standard deviation). Next, averages of the standardized RSQ and RQ values were created for each individual. Thus, each participant received a continuous index score reflecting the degree to which he/she demonstrates each of the 4 attachment styles relative to others in the sample (rather than an absolute quantity of a trait). The sample means and standard deviations for each of the four attachment index scores were approximately 0 and 1, respectively. The internal consistencies of the index scores for this sample were in the low to moderate range (secure: r= 0.58; preoccupied: r= 0.64; fearful r= 0.71; dismissive: r= 0.65) but were consistent with the range of internal consistency indices of self-report adult attachment measures as reported by Ravitz et al (Ravitz et al., 2010). Although categorical measures (i.e., classifying each participant as having one predominant style) can provide ease of interpretation and utility in clinical settings (Kidd, Hamer, & Steptoe, 2011; Maunder & Hunter, 2009), we used continuous dimensional measures for the current study because they may provide greater informational value that can be lost through categorization.

Perceived spouse responses to pain behavior

The Spouse Response Inventory (SRI) (Schwartz, Jensen, & Romano, 2005) assesses perceptions of spouse responses (from the perspective of the individual with chronic pain) to pain behaviors, including subscales assessing solicitous responses to pain behaviors (19 items) and negative responses to pain behaviors (7 items). Participants rate how often their significant other responds in each area on a 5-point Likert scale. Subscale scores are obtained by averaging the responses given for each item in that subscale. The subscales of the SRI have demonstrated high test-retest reliability over a two week period (range r = .73 to .84) and strong internal consistency (range α = 0.81 to 0.93) for a sample of mixed chronic pain patients (Pence, Thorn, Jensen, & Romano, 2008; Schwartz et al., 2005) and the current sample (range α=0.90- 0.94).

Pain intensity

The Wisconsin Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) provides a brief measure of pain intensity (Cleeland, 1989). The BPI is applicable to the assessment of pain in persons with chronic, non-malignant pain (Keller et al., 2004; Tan, Jensen, Thornby, & Shanti, 2004). Respondents rate their most severe pain from the past week, average pain from the past week, least pain from the past week, and current pain on an 11-point Likert scale. The mean of these items represents the pain intensity score, which has demonstrated strong internal consistency in other studies (Cronbach's α=0.85-0.89) (Keller et al., 2004; Tan et al., 2004) and the current sample (α=0.82).

Self-reported Pain Behavior

The Pain Behavior Checklist (PBCL) (Kerns, Haythornthwaite, Rosenberg, Southwick, & et al., 1991) is a widely-used measure of self-reported behaviors indicative of pain, including distorted ambulation, negative affect, facial or audible expressions of distress, and avoidance of activity. Participants rate how often they engage in each of 17 possible pain behaviors on a 7-point Likert scale. A total score can be calculated that has been shown to be internally consistent (Cronbach's α=0.85; current α=0.90),stable over 2 to 3 weeks (r = 0.80) (Kerns et al., 1991), and correlated with observed pain behavior (r=-0.30-0.51)(Romano, Jensen, Turner, Good, & Hops, 2000; Romano et al., 1988).

Disability

The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, 11-item version (RMDQ-11) (Stroud, McKnight, & Jensen, 2004) measures disability in terms of limitations in daily activities. Participants endorse items that are currently true for them. A total score is obtained by summing the number of items endorsed (range = 0-11). The RMDQ-11 has demonstrated strong reliability (Cronbach's α=0.88; current α=0.80), concurrent validity, and associations with the parent scale (r=0.93) (Stroud et al., 2004).

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977) is a 20-item questionnaire measuring depressive symptoms. Respondents are asked to rate the frequency with which each item occurred over the previous 7 days on a 4-point Likert scale. Total scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. The CES-D has demonstrated high reliability in a general population as well as a psychiatric population (α=0.85 and α=0.90, respectively) (Radloff, 1977) and in the current sample (α=0.92). Researchers have found the CES-D to be valid for use with chronic pain populations (Blalock, DeVellis, Brown, & Wallston, 1989; Geisser, Roth, & Robinson, 1997; Turk & Okifuji, 1994).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., 2007). Prior to analysis, the data were examined using frequencies and descriptive statistics. Differences between groups were tested using independent samples t-tests (normally distributed, continuous dependent variables), Mann-Whitney tests (non-normally distributed, continuous dependent variables) or χ2 tests (categorical dependent variables). Pearson correlations were used to determine associations between pain criterion variables, attachment style, and perceived spouse responses to pain behavior. Preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure that the assumptions for multiple linear regression were met.

Linear regression models were used to identify the predictors of self-reported pain behaviors and depressive symptoms. Control variables were entered into the model, consisting of pain source (persons with headache or musculoskeletal pain vs. persons with a history of amputation) and pain intensity. Thus the analyses were designed to examine the effects of attachment and spouse responses over and above any effect of pain (intensity and type) per se. Then the following predictors were entered in the following order: (1) attachment style index scores (secure, fearful, preoccupied, and dismissive)(step 1); (2) perceived spouse responses to pain behavior (solicitous responses and negative responses)(step 2); and (3) interactions between solicitous responses and each attachment index and between negative spouse responses and each attachment index (step 3).

The total number of participants available for the regression analyses (N=182) exceeded the number deemed necessary (N=170) to have an adequate sample to predictor ratio for models testing 7 main effects and 8 interactions (i.e., 50 + 8m, where m = the number of predictors in the model) (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996). Pain behavior and depressive symptoms were selected as the pain criterion to be modeled in order to balance parsimony of analyses and inclusiveness of outcomes commonly investigated in studies of adaptation to chronic pain, particularly studies related to spouse responses to patient pain behavior and to facilitate interpretation of results as noted previously. The tests of R2 change served as an omnibus test for each block of predictors. If the omnibus test was significant, univariate regression analyses were used to test for significant relations. This method, termed “protected t-tests” (DeCoster, 2005) reduces the chances of Type I error, while allowing for more powerful tests compared to using statistical corrections such as the Bonferroni correction, which assumes independence of tests.

The above interaction analyses serve to test attachment style as a moderator of the relations between perceived spouse responses and self-reported pain behavior and depression. Moderator variables affect the direction and/or strength of the association between a predictor (in this case, perceived spouse response) and criterion variables (in this case, pain behavior and depression) (Baron & Kenny, 1986). We next describe exploratory analyses intended to identify potential mediators of any relationships found between attachment style and pain-related outcomes. Mediator variables account for or explain the relation between a predictor (in this case, attachment style) and criterion variables (in this case, pain related outcomes)(Baron & Kenny, 1986). Understanding the circumstances in which observed associations hold (moderators) and the mechanisms by which constructs are related to each other (mediators) increases the generalizability and clinical utility of research findings, and may help to explain inconsistent research findings and generate hypotheses for new studies and interventions.

To identify potential mediators of any relationships found between attachment style and pain-related outcomes, we conducted exploratory tests of perceived spouse responses as a mediator of the significant associations observed between attachment style and pain behavior and depression in the multivariable regression models when perceived response were significantly correlated with attachment style. First, Baron and Kenny's criteria (Baron & Kenny, 1986) were tested. Next, mediation was tested using the non-parametric bootstrapping procedure (3000 re-samples) to estimate the indirect effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). Mediation is indicated if the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the indirect effect does not include 0. All mediation models adjusted for pain source, pain intensity, and perceived solicitous spouse responses.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The sample was primarily female, Caucasian, and married (Table 1). On average, participants reported relatively long duration of both their relationship (mean=20.27 years, sd=13.75) and their pain (mean=17.47 years, sd=13.16). The sample was heterogeneous with respect to pain conditions. Participants reported between 1 and 9 different pain sources, with approximately 75% of the sample reporting at least 2 different sources of pain. The most commonly reported pain sources were back (65.9%), head (50.0%), leg, foot, or ankle (29.7%), and neck (26.9%). Females reported higher pain intensity (t=-2.84, p<0.01) and depressive symptoms (t=-2.58, p<0.05) than males. There were no gender differences in age, length of marriage/cohabitation, pain duration, attachment style, perceived spouse responses to pain behavior, or pain criterion variables (all p>0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic and pain criterion variables of participants (N=182)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 74 (40.7%) |

| Female | 107 (58.8%) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 165 (90.7%) |

| African-American | 6 (3.3%) |

| Native American/Alaska Native | 6 (3.3%) |

| Other | 5 (2.7%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 175 (96.2%) |

| Cohabitating | 7 (3.8%) |

| Number of pain sources | |

| 1 | 46 (25.3%) |

| 2+ | 136 (74.7%) |

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.36 (12.11) |

| Duration of marriage or cohabitation with current spouse (years) | 20.20.27 (13.75) |

| Pain duration, earliest pain condition (years) | 17.47 (13.16) |

| Pain behaviors (PBCL) | 42.85 (20.84) |

| Pain intensity (BPI) | 4.77 (1.58) |

| Disability (RMDS) | 6.34 (3.83) |

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D) | 21.21 (10.92) |

| Solicitous Responses to Pain (SRI) | 2.25 (0.91) |

| Negative Responses to Pain (SRI) | 0.70 (0.81) |

Note: Because the index scores for each of the four attachment styles are comprised of 2 standardized scores, they by definition have sample means of approximately 0 and sample standard deviations of approximately 1.

Bivariate associations between attachment styles, pain criterion variables (pain behavior, pain intensity, disability, depression), and perceived spouse responses to pain behavior

Secure attachment was significantly inversely associated with self-reported pain behaviors, pain intensity, disability, and depressive symptoms (all p<0.05; Table 2). Preoccupied and fearful attachment styles were significantly positively associated with self-reported pain behaviors, pain intensity, disability, and depressive symptoms (all p <0.05). Dismissive attachment was not significantly associated with any of these criterion variables. Although none of the attachment styles were associated significantly with perceived solicitous responses to pain behavior, secure attachment was inversely associated with perceived negative responses to pain and fearful and preoccupied attachment were positively associated with perceived negative responses to pain (all p<0.01).

Table 2.

Correlations of attachment style, perceived spouse responses, and pain criterion variables

| Secure Attachment (RSQ) | Preoccupied Attachment (RSQ) | Fearful Attachment (RSQ) | Dismissive Attachment (RSQ) | Solicitous Responses to Pain (SRI) | Negative Responses to Pain (SRI) | Pain Behaviors (PBCL) | Pain Intensity (BPI) | Disability (RMDS) | Depressive Symptoms (CES-D) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | -- | −0.11 | −0.53*** | −0.28*** | 0.07 | −0.25*** | −0.28*** | −0.22** | −0.18* | −0.38*** |

| Preoccupied | -- | -- | 0.23** | −0.1 | −0.14 | 0.34*** | 0.25*** | 0.17* | 0.16* | 0.23** |

| Fearful | -- | -- | -- | 0.44*** | −0.11 | 0.22** | 0.297*** | 0.18* | 0.18* | 0.39*** |

| Dismissive | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| Solicitous Responses | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.39*** | 0.33*** | 0.19** | 0.17* | 0.07 |

| Negative Responses | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.28*** | 0.29*** | 0.27*** | 0.41*** |

| Pain Behaviors | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.53*** | 0.63*** | 0.57*** |

| Pain Intensity | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.42*** | 0.50*** |

| Disability | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.45*** |

p < 0.05

p <0 .01

p < 0.001

Reported solicitous responses were significantly associated with self-reported pain behaviors (p<0.001), pain intensity (p<0.01) and disability (p<0.05) but not depressive symptoms, whereas reported negative responses were significantly associated with self-reported pain behaviors, pain intensity, disability and depressive symptoms (all ps<0.001) (Table 2). The attachment style variables showed significant intercorrelations as shown in Table 2, with secure attachment being significantly negatively correlated with preoccupied and fearful attachment (both ps<0.001), and fearful attachment being positively correlated with dismissing (p<0.001) and preoccupied (p<0.01) attachment.

Multivariable associations between attachment style and criterion variables (pain behavior, depression) and tests of moderation of the pain behavior response-criterion associations by attachment styles

For the model predicting self-reported pain behavior, the attachment styles collectively made a significant contribution to the model after accounting for pain source and pain intensity (r2 change= 0.07, p < 0.01) (Table 3). Preoccupied attachment style was positively associated with pain behavior (p<0.05). In the next step, perceived spouse responses to pain were significantly associated with pain behavior (r2 change= 0.13, p < 0.001), such that both perceived solicitous responses and perceived negative responses were positively associated with pain behavior (p<0.001). The interactions between attachment style and perceived spouse responses to pain behavior did not contribute significantly to the model (r2 change=0.01, p>0.05).

Table 3.

Self-reported pain behavior (PBCL) regressed on perceived responses to pain, attachment style, and their interaction

| F Change | R2Change | B (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables: | 34.23*** | 0.28 | |

| Pain source (ref= musculoskeletal pain) | −1.61 (3.53) | ||

| Pain intensity | 6.77 (0.89)*** | ||

| Step 1: Attachment variables | 4.55** | 0.07 | |

| Secure | −2.17 (1.85) | ||

| Preoccupied | 3.53 (1.57)* | ||

| Fearful | 2.54 (1.89) | ||

| Dismissive | 1.62 (1.76) | ||

| Step 3: Perceived spouse responses to pain behavior | 20.81*** | 0.13 | |

| Solicitous responses to pain behavior | 9.38 (1.47)*** | ||

| Negative responses to pain behavior | 6.57 (1.78)*** | ||

| Step 4: Interactions | 0.50 | 0.01 |

p <0 .05

p <0 .01

p <0 .001

In the model predicting depressive symptoms, the attachment styles were significantly associated with depressive symptoms after controlling for pain source and pain intensity (r2 change= 0.12, p<0.001)(Table 4) Specifically, secure attachment was inversely associated with depressive symptoms and fearful attachment was positively associated with depressive symptoms (p<0.05). In the next step, perceived spouse responses to pain significantly predicted depressive symptoms (r2 change= 0.06, p < 0.001). Both perceived solicitous and perceived negative responses were positively associated with depressive symptoms (p<0.05). The interactions between attachment style and perceived spouse responses to pain behavior did not contribute significantly to the model (r2 change=0.02, p>0.05).

Table 4.

Depressive symptoms (CES-D scores) regressed on perceived responses to pain, attachment style, and their interaction

| F Change | R2 Change | B (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables: | 34.08*** | 0.27 | |

| Pain source (ref= musculoskeletal pain) | −4.19 (1.85)** | ||

| Pain intensity | 3.00 (0.47)*** | ||

| Step 2: Attachment variables | 8.58*** | 0.12 | |

| Secure | −1.86 (0.93)* | ||

| Preoccupied | 2.21 (0.79) | ||

| Fearful | 2.66 (0.95)** | ||

| Dismissive | 0.28 (0.89) | ||

| Step 3: Perceived spouse responses to pain behavior | 8.16*** | 0.05 | |

| Solicitous responses to pain behavior | 1.80 (0.79)* | ||

| Negative responses to pain behavior | 3.81 (0.95)*** | ||

| Step 4: Interactions | 0.71 | 0.02 |

p <0 .05

p <0 .01

p <0 .001

Exploratory Mediation Analyses

We conducted exploratory analyses to determine whether perceived negative spouse responses would mediate observed associations between attachment style and pain-related outcomes. Three exploratory mediation models were tested based on the unique associations observed between attachment style and pain criterion variables in the multivariable regression models and correlations between attachment style and perceived spouse responses.

We first tested whether perceived negative responses mediated the positive association between preoccupied attachment and self-reported pain behavior. The total effect of preoccupied attachment on pain behavior was significant (c1(se)=5.18 (1.47), p<0.01) and preoccupied attachment was associated with perceived negative spouse responses to pain (a1(se)=0.21 (0.06), p<0.001). Perceived negative responses were associated with pain behavior after adjustment for preoccupied attachment (b1(se)=7.45 (1.80), p=0.001). Finally, the direct effect of preoccupied attachment on pain behavior was reduced but remained significant after adjustment for perceived negative spouse responses (c1’(se)=3.63 (1.46), p<0.05) and the indirect effect was also significant (a1*b1= 1.53, 95% CI=0.63, 3.11). Thus, perceived negative spouse responses partially mediated the association between preoccupied attachment and self-reported pain behavior.

We next tested whether perceived negative responses mediated the inverse association between secure attachment and depressive symptoms. The total effect of secure attachment on depressive symptoms was significant (c2(se)=-3.52 (0.83), p<0.001) and secure attachment was inversely associated with perceived negative spouse responses to pain (a2(se)=-0.14 (0.06), p<0.05). Perceived negative responses were associated with depressive symptoms after adjustment for secure attachment (b2(se)=4.13 (0.94), p<0.001). Finally, the direct effect of secure attachment on depressive symptoms was reduced but remained significant after adjustment for perceived negative spouse responses (c2’(se)=-2.94 (0.81), p<0.001) and the indirect effect was also significant (a2*b2=-0.58, 95% CI=-1.37, -0.11). Thus, perceived negative spouse responses partially mediated the inverse association between secure attachment and depressive symptoms.

Finally, we tested whether perceived negative responses mediated the positive association between fearful attachment and depressive symptoms. The total effect of fearful attachment on depressive symptoms was significant (c3(se)=3.93(0.76), p<0.001). However, after adjustment for covariates, fearful attachment was not significantly associated with perceived negative spouse responses to pain (a3(se)=0.10 (0.06), p=0.08). Therefore, this mediation model was not supported.

Discussion

This study examined adult attachment styles in relationship to pain outcomes and the social context of chronic pain. Drawing on the ADMC(Meredith et al., 2008) as well as cognitive behavioral formulations, we sought to determine whether both enduring interpersonal patterns, such as attachment style, and contemporaneous social interactions, such as reported spouse responses to pain behavior, are associated with adjustment and functioning in chronic pain. We found that attachment style is related to important pain-related variables, including self-reported pain, pain behavior, dysfunction, and depressive symptoms, in individuals with various types of chronic pain, suggesting the applicability of this concept to a range of important pain outcomes and types.

As predicted, secure attachment style was associated with significantly lower levels of self-reported pain, pain behavior, disability and depressive symptoms in correlational analyses. Also consistent with our hypotheses, both insecure attachment styles characterized by negative models of the self (preoccupied and fearful) were associated with significantly higher levels of patient-reported pain, pain behavior, disability, and depressive symptoms. Dismissive attachment style, marked by negative models of others but positive of self, was not associated with these pain and pain-related criterion variables. Also consistent with attachment concepts, fearful and preoccupied attachment styles were associated directly, and secure attachment style inversely, with reported spouse negative responses to pain behaviors. Perceived solicitous responses, however, were not associated with attachment style. Whether the association of fearful and preoccupied attachment styles and the report of negative responses from others reflect higher rates of actual negative behavior by others or a heightened tendency to perceive responses as negative when fearful and preoccupied attachment styles are stronger is unclear, and cannot be determined without corroborating behavioral data.

A key finding of the study was that both spouse responses to pain behaviors and attachment styles made significant independent contributions to the prediction of pain behavior and depression. Preoccupied attachment style was significantly associated with higher rates of self-reported pain behavior even when pain intensity and group were controlled. Likewise, secure and fearful attachments styles made significant independent contributions to the prediction of depressive symptoms with pain intensity and group controlled. We also found, consistent with prior literature, that perceived solicitous spouse responses were directly associated with more pain behavior and inversely associated with depressive symptoms. Spouse negative behavior was directly associated with more pain behavior as well as with more depressive symptoms, suggesting that perceived negative responses may not function to suppress pain behavior, but rather may be associated with increased distress and its expression.

The study hypotheses concerning the moderating effects of attachment styles on the prediction of pain behaviors and depression were not supported; that is, attachment style did not enhance or dampen the association of perceived spouse responses with pain-related outcomes. This raises several possibilities. One is that attachment styles and social responses to pain behaviors may operate independently and be additive, but not synergistic, in their effects. If this is the case, it would be important to determine this and take both processes into account in understanding adjustment to chronic pain and designing interventions. Another possibility is that our current measurement strategy was inadequate to detect moderation effects and that use of different measures of patient-spouse interaction (including direct observation) or other ways of measuring attachment styles may allow these to emerge.

Attachment style is posited to be shaped in large part by early life events and to be somewhat stable throughout life; therefore, we conceptualized it as a potential moderator variable that might influence the extent to which social responses are related to pain outcomes. Given that we did not find moderating effects for attachment, but did find significant associations between perceived negative responses to pain behavior and attachment styles as well as pain outcomes, we conducted exploratory analyses to determine whether perceived negative responses might mediate the relationship between attachment style and pain-related outcomes. We found that the role of perceived negative responses by spouses may be a more crucial potential link between attachment styles and adjustment in chronic pain than perceived solicitous responding. Perceived negative, but not solicitous, spouse responses partially mediated the association between preoccupied attachment and self-reported pain behaviors and the inverse association between secure attachment and depressive symptoms. These analyses suggest that attachment style may influence how patients perceive and evaluate negative spouse responses, which in turn are associated with higher levels of pain behavior and depressive symptoms. Thus, this study identifies one possible pathway through which the attachment framework may be associated with adaptation to chronic pain. If confirmed in further research, this result suggests that these insecure attachment styles, which have in common negative views of the self, may confer additional risk for poor adjustment and also suggests that negative spouse responses (either perceived or actual) are worthy of further study as a potential intervention target among individuals evidencing these attachment styles.

Several possible explanations can be entertained for the finding of partial mediation but not the hypothesized moderation effects. It may indeed be the case that, as our findings suggest, attachment style does not moderate the relationship between spouse responses and the outcomes measured in this study. Another possibility is that the inter-relationships among attachment style scores precluded an adequate test of moderation effects. Although adult attachment has been described in terms of different predominant styles, it is possible that individuals may exhibit a mix of attachment tendencies, as evidenced by significant associations among the attachment style scores found in this study. Fearful attachment was significantly positively correlated with both preoccupied and dismissive attachment, although the types of predictions one might make concerning these attachment styles and their interaction with social responses might be quite different. Another possibility is that factors other than those we measured in the current study, such as current relationship satisfaction or other unmeasured personality variables, may be more determinative of how influential social responses of spouses are in predicting pain behaviors and depressive symptoms than attachment style. However, our mediational findings do suggest that attachment style, at least in part, may affect perceptions of spouse behaviors, which in turn can influence pain outcomes.

A number of study limitations should be noted in interpreting its findings. Although the response rates for this study were comparable to that of most survey studies (Baruch, 1999), it is unknown whether non-respondents differed systematically from respondents on relevant variables. For example, it is not clear whether attachment style might have affected the likelihood of study completion, particularly since both the individual with chronic pain and her or his spouse were required to participate. It is possible, for example, that insecure attachment in either the person with pain or spouse might result in a lower response rate, possibly due to more negative views of self or others, resulting in under-representation of couples having at least one individual with this attachment style. The associations between attachment style and pain criterion variables for these unrepresented individuals may differ from what was observed in the study sample. Additionally, this study is based on self-report data; therefore, some of the significant associations found may be due to shared method variance. This study would be strengthened by the inclusion of additional sources of data such as direct observation or spousal reports. Further, the attachment indices in the current study demonstrated low to moderate internal consistencies. However our observed internal consistency measures for the attachment indices are consistent with previous published work (Ciechanowski et al., 2003; Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994a) and the extensive review by Ravitz et al (2010) of attachment measures. Further, in spite of challenges in measuring the construct of attachment, this study, along with a growing body of literature reviewed above, continues to find important relationships between attachment style as measured and adaptation to chronic pain. A further limitation is that this study is correlational and the current methods did not permit a test of causal relations. Finally, although the heterogeneous pain sample was a strength of this study and serves to maximize the generalizability of our findings, our findings may not generalize to all individuals with chronic pain.

Despite the limitations noted previously, this study offers a unique opportunity to simultaneously consider the role of both attachment processes and spouse responses in adaptation to chronic pain, and to connect two important bodies of literature on relationships and pain that to date have remained separate. The ADMCP has provided an important heuristic model for how attachment patterns may form a diathesis which, in combination with cognitive appraisals and responses to appraisals such as coping, may impact adjustment (Meredith et al., 2008). However, while perceptions of social support are acknowledged as a type of cognitive appraisal within this model, the role of spouse or other responses in the social environment are not explicitly incorporated. Integrating social context and attachment perspectives has the potential to expand and provide a more elaborated understanding of how potentially enduring interpersonal patterns such as attachment style and day-to-day interactions with significant others might both influence adjustment and functioning in chronic pain. Although the study findings must be considered preliminary until replicated in further research, if confirmed they may have implications for treatment development. Future interventions targeting the social environment may be more effective if they account for both perceived responses and attachment style, tailoring interventions modifying pain behaviors and responses of others in ways that are congruent with the attachment style of individuals with chronic pain and potentially their significant others.

Impact and Implications.

In spite of the importance of both attachment processes and the social context for adaptation to pain, to our knowledge, this is the first study to simultaneously examine the complex associations among attachment style, spouse responses to pain behavior, and adaptation to chronic pain.

This study found that attachment style is associated with both adaptation to chronic pain and perceived spouse response; in fact, perceived negative spouse responses to pain behavior partially explained some associations between attachment style and pain behavior and depressive symptoms.

Understanding associations between attachment styles and adaptation to chronic pain has the potential to inform treatment development efforts and tailoring of treatments to individual needs. If future research confirms these findings, assessment and subsequent clinical attention to both attachment and spouse responses might enhance overall adaptation to chronic pain. Furthermore, individuals found to have preoccupied or fearful attachment styles might benefit from elements of care that those with secure attachment styles may not need.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by funding from the National Headache Foundation (Co-PIs: Laura Forsythe, Beverly Thorn) and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Center for Rehabilitation Research (grant no. P01 HD33988, PI: Mark Jensen).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Ahrens KR, Ciechanowski P, Katon W. Associations between adult attachment style and health risk behaviors in an adult female primary care population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2012;72(5):364–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological research-conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz L. Attachment styles among young adults: A test-of a four category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991a;61:226–224. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991b;61(2):226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruch Y. Response rate in academic studies: A compariative analysis. Human Relations. 1999;52(4):421–438. [Google Scholar]

- Blalock SJ, DeVellis RF, Brown GK, Wallston KA. Validity of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale in arthritis populations. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32(8):991–997. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Volume 3 sadness and depression. Basic Books; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J, editor. Attachment and loss: Volume 1: Attachment. 2nd ed. Basic Books; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Gillis M, Heinz W, Geisser ME, Foran H. Marital functioning, chronic pain, and psychological distress. Pain. 2004;107(1-2):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Weisberg JN, Gallagher RM. Marital satisfaction and pain severity mediate the association between negative spouse responses to pain and depressive symptoms in a chronic pain patient sample. [doi:10.1046/j.1526-4637.2000.99100.x]. Pain Medicine. 2000;1(1):35–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2000.99100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanowski P, Sullivan M, Jensen M, Romano J, Summers H. The relationship of attachment style to depression, catastrophizing and health care utilization in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2003;104(3):627–637. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Walker EA. The patient-provider relationship: Attachment theory and adherence to treatment in diabetes. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(1):29–35. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland C. Measurement of pain by subjective report. In: Chapman C, Loeser J, editors. Issues in pain measurement. Advances in pain research and therapy. Vol. 12. Raven Press; New York: 1989. pp. 391–403. [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58(4):644–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies KA, Macfarlane GJ, McBeth J, Morriss R, Dickens C. Insecure attachment style is associated with chronic widespread pain. Pain. 2009;143(3):200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCoster J. Applied linear regression. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.stat-help.com.

- Fillingim RB, Doleys DM, Edwards RR, Lowery D. Spousal responses are differentially associated with clinical variables in women and men with chronic pain. [doi:10.1097/00002508-200307000-00004]. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2003;19(4):217–224. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fordyce W. Behavioral methods for chronic pain and illness. The C.V. Mosby Company; Saint Louis: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Geisser ME, Roth RS, Robinson ME. Assessing depression among persons with chronic pain using the center for epidemiological studies-depression scale and the beck depression inventory: A comparative analysis. Clin J Pain. 1997;13(2):163–170. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199706000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin DW, Bartholomew K. The metaphysics of measurement: The case of adult attachment Attachment processes in adulthood. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; London, England: 1994a. pp. 17–52. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin DW, Bartholomew K. Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994b;67(3):430–445. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52(3):511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(5):309–318. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200409000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns RD, Haythornthwaite J, Rosenberg R, Southwick S, et al. The pain behavior check list (pbcl): Factor structure and psychometric properties. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1991;14(2):155–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00846177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns RD, Haythornthwaite J, Southwick S, Giller EL., Jr. The role of marital interaction in chronic pain and depressive symptom severity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1990;34:401–408. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90063-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd T, Hamer M, Steptoe A. Examining the association between adult attachment style and cortisol responses to acute stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(6):771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. On being insecure about the assessment of attachment styles. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2002;19:811–834. [Google Scholar]

- Maunder RG, Hunter JJ. Assessing patterns of adult attachment in medical patients. [doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.10.007]. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31(2):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams LA, Asmundson GJ. The relationship of adult attachment dimensions to pain-related fear, hypervigilance, and catastrophizing. Pain. 2007;127(1-2):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams LA, Holmberg D. Adult attachment and pain catastrophizing for self and significant other. Pain. 2010;149(2):278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith P, Ownsworth T, Strong J. A review of the evidence linking adult attachment theory and chronic pain: Presenting a conceptual model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(3):407–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith P, Strong J, Feeney JA. Adult attachment, anxiety, and pain self-efficacy as predictors of pain intensity and disabiltiy. Pain. 2006;123:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment, group-related processes, and psychotherapy. Int J Group Psychother. 2007;57(2):233–245. doi: 10.1521/ijgp.2007.57.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ognibene TC, Collins NL. Adult attachment styles, perceived social support and coping strategies. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1998;15(3):323–345. [Google Scholar]

- Pegman S, Beesley H, Holcombe C, Mendick N, Salmon P. Patients' sense of relationship with breast cancer surgeons: The relative importance of surgeon and patient variability and the influence of patients' attachment style. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;83(1):125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence LB, Thorn BE, Jensen MP, Romano JM. Examination of perceived spouse responses to patient well and pain behavior in patients with headache. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(8):654–661. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31817708ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Spss and sas procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods Instruments & Computers. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The ces-d scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measures. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ravitz P, Maunder R, Hunter J, Sthankiya B, Lancee W. Adult attachment measures: A 25-year review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010;69(4):419–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano J, Cano A, Schmaling K. Assessment of couples and families with chronic pain. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of pain assessment. 3rd ed. The Guilford Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Romano JM, Jensen MP, Turner JA, Good AB, Hops H. Chronic pain patient–partner interactions: Further support for a behavioral model of chronic pain. [doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(00)80023-4]. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31(3):415–440. [Google Scholar]

- Romano JM, Syrjala KL, Levy RL, Turner JA, Evans P, Keefe FJ. Overt pain behaviors: Relationship to patient functioning and treatment outcome. Behavior Therapy. 1988;19(2):191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Romano JM, Turner J, Jensen M, Friedman L, Bulcroft RA, Hops H. Sequential analysis of chronic pain behaviors and spouse responses. Pain. 1995;63(353-360) doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfe E, Bartholomew K. Reliability and stability of adult attachment patterns. Personal Relationships. 1994;1:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz K, Slater MA, Birchler GR. The role of pain behaviors in the modulation of marital conflict in chronic pain couples. Pain. 1996;65(2-3):227–233. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz L, Jensen MP, Romano JM. The development and psychometric evaluation of an instrument to assess spouse responses to pain and well behavior in patients with chronic pain: The spouse response inventory. J Pain. 2005;6(4):243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Nelligan JS. Support seeking and support giving within couples in an anxiety-provoking situation: The role of attachment styles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62(3):434–446. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. Spss for windows, release 16.0.1. Chicago: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud MW, McKnight PE, Jensen MP. Assessment of self-reported physical activity in patients with chronic pain: Development of an abbreviated roland-morris disability scale. J Pain. 2004;5(5):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 3rd ed. Harper Collings; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the brief pain inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain. 2004;5(2):133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk DC, Kerns RD, Rosenburg R. Effects of marital interaction on chronic pain and disability: Examining the down side of social support. Rehabilitation Psychology. 1992;37:259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Turk DC, Okifuji A. Detecting depression in chronic pain patients: Adequacy of self-reports. Behav Res Ther. 1994;32(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]