Abstract

Polyaromatic compounds are well-known to intercalate DNA. Numerous anticancer chemotherapeutics have been developed upon the basis of this recognition motif. The compounds have been designed such that they interfere with the role of the topoisomerases, which control the topology of DNA during the cell-division cycle. Although many promising chemotherapeutics have been developed upon the basis of polyaromatic DNA intercalating systems, these candidates did not proceed past clinical trials on account of their dose-limiting toxicity. Herein, we discuss an alternative, water-soluble class of polyaromatic compounds, the 2,9-diazaperopyrenium dications, and report in vitro cell studies for a library of these dications. These investigations reveal that a number of 2,9-diazaperopyrenium dications show similar activities as doxorubicin toward a variety of cancer cell lines. Additionally, we report the solid-state structures of these dications, and we relate their tendency to aggregate in solution to their toxicity profiles. The addition of bulky substituents to these polyaromatic dications decreases their tendency to aggregate in solution. The derivative substituted with 2,6-diisopropylphenyl groups proved to be the most cytotoxic against the majority of the cell lines tested. In the solid state, the 2,6-diisopropylphenyl-functionalized derivative does not undergo π···π stacking, while in aqueous solution, dynamic light scattering reveals that this derivative forms very small (50–100 nm) aggregates, in contrast with the larger ones formed by dications with less bulky substituents. Alteration of the aromaticitiy in the terminal heterocycles of selected dications reveals a drastic change in the toxicity of these polyaromatic species toward specific cell lines.

Keywords: anticancer activity, diazaperopyrenium dications, DNA intercalation

One of the major strategies employed in cancer chemotherapy1,2 is the use of small molecules that disrupt DNA replication and so halt rapid cellular division and promote cell apoptosis. To this end, molecules that intercalate double-stranded DNA have shown promise as anticancer agents often as a result of the inhibition of topoisomerase enzymes.3−5 Intercalating compounds include ethidium bromide,6−11 proflavine11−16 and doxorubicin,3,17−22 the last of which has been approved clinically and is administered as the hydrochloride salt in the clinic to treat a variety of cancers. Although effective as a chemotherapeutic agent, prolonged therapeutic regiments using doxorubicin lead to serious adverse implications17,22 for the cardiovascular system, the most significant17 of which is cardiomyopathy. Continuing efforts, therefore, to uncover alternative drug candidates for anticancer treatments to improve upon established therapeutics remains a top priority in the eyes of medicinal chemists. From these continuing efforts, other DNA-intercalating drug candidates, such as Mitonafide23,24 and Amodafide25,26 and the bis-intercalating Elinafide,27−30 have been identified31−33 and shown to be highly cytotoxic to cancer cells. After numerous clinical studies29 of these candidates, however, many compounds have yet to be developed as chemotherapeutic agents on account of their dose-limiting toxicity. In order to develop new drugs that follow the established DNA-intercalation pathway, and yet have different pharmacokinetics, we need to find out more about the physical properties of the drug candidates. The most common structural feature of these DNA intercalators is the presence of a planar aromatic region to aid and abet stacking in between the DNA bases. Although there are many examples of anticancer drug candidates, such as naphthalene diimide-based compounds,33 containing extended aromatic regions, their low solubilities in aqueous solutions have often limited anticancer therapeutic-based applications. Molecules which contain an aromatic region, while remaining water-soluble, are particularly promising drug candidates. These two properties are especially true for cationic DNA intercalators, since investigations34,35 have shown that electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged phosphate backbone of DNA can leverage attractive Coulombic intercalation interactions.

Recently, we have been investigating36−39 the materials properties of the N,N′-dimethyl-2,9-diazaperopyrenium dication (dimethyl-DAPP2+), which has (Figure 1) an extended, electron-rich aromatic core region flanked on either side by electron-deficient pyridinium rings. This compound has found use in mechanically interlocked molecules36 (MIMs), graphene exfoliation applications,39 and in host–guest inclusion complexes.37,38 The aqueous solubility, imparted by the dicationic nature of this compound, led us to consider whether the extended aromatic region present in dimethyl-DAPP2+ and related compounds could prove useful in identifying cancer therapeutic agents. The interactions of the dimethyl-DAPP2+ dication with DNA have been investigated40,41 previously, and there have been indications40,41 that this dication can intercalate DNA, with a preference for G-C pairs over the A-T pairs. Additionally, it has been demonstrated40 that dimethyl-DAPP2+ can be used as a selective fluorophore to detect A- and T-rich single-stranded polynucleotides, as well as having the potential to act as a sequence-specific artificial photonuclease.

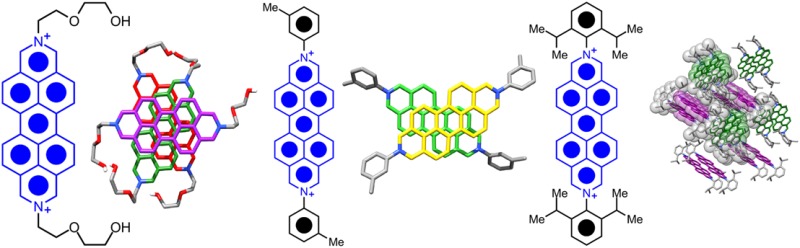

Figure 1.

Structural formulas for the DAPP2+1·2Cl–8·2Cl derivatives that have been screened for anticancer activity. Numbering on the general structural formula indicates the substitution position on the DAPP2+ dication.

To the best of our knowledge, no cancer cell proliferation studies have been carried out on the DAPP2+ dication, yet perylene analogues have been tested42 for DNA telomerase inhibition while the structurally related diazapyrenium dications have been reported43−45 to have encouraging therapeutic properties. 4,9-Diazapyrenium dications have been shown43−45 to be able to intercalate DNA, and cancer-cell proliferation investigations have been carried out against human malignant MiaPaCa 2 (pancreatic), and Hep 2 (laryngeal) cell lines, in addition to the normal human fibroblast WI-38 cell line using two derivatives of these dications. It was found45 that treatment of these cell lines with 4,9-diazapyrenium derivatives, in concentrations ranging from 100 nM to 100 μM, resulted in growth inhibition in excess of 50%, as well as their being more specific against the cancer cell lines than the WI-38 cell line. Additionally, the 2,7-diazapyrenium dication has been demonstrated46 to undergo photochemical clevage of both supercoiled DNA pBR322 and DNA M13mp19.

Given the anticancer activity of the diazapyrenium dications, we might expect that the DAPP2+ dications would also possess anticancer activity, and may be more effective intercalators than the diazapyrenium dications on account of their extended polyaromatic cores. In our research on these dications, we sought to test the anticancer activity of a library of compounds. Since small structural variations may result in substantial differences in therapeutic activity and, given the fact that the dimethyl-DAPP2+ dication is capable of homophilic recognition, we synthesized a small library of compounds which can influence directly the way in which the dications interact with each other in solution. A cell proliferation assay was run in order to test the activity of each member of the library and we discovered that one candidate in particular has promising efficacy. Additionally, we have tested the efficacy of DAPP2+-related compounds with different levels of aromaticity and found that there is a considerable difference between the potency of the completely aromatic diazaperopyrenium dications and the hexahydroanthradiisoquinoline dications, which have less aromaticity, with the same functional groups on the 2 and 9 positions.

Results and Discussion

Eight different DAPP2+ dications 12+–82+ were synthesized with a range of different substituents on the nitrogens. Modification of these substituents changes the manner in which the dications aggregate in solution and in the solid state. This difference in packing has been observed47−52 previously for perylene diimides, where the presence of large substituents on the imide nitrogens limit π···π aggregation without influencing the planarity of the central perylene core. Although substitution on the bay (5, 6, 12, and 13, Figure 1) positions of perylene diimides also limits50,53−56 π···π aggregation, this substitution pattern results in conformational twisting of the perylene core. The eight different DAPP2+ dications were prepared by difunctionalization of the nitrogens located at the 2 and 9 positions. This protocol enables the preparation of the dichloride salts (Figure 1) where R = Me (1·2Cl), Et (2·2Cl), iPr (3·2Cl), N3CH2CH2 (4·2Cl), HOCH2CH2OCH2CH2 (5·2Cl), p-MeC6H4 (6·2Cl), m-MeC6H4 (7·2Cl), and 2,6-iPr2C6H3 (8·2Cl). These N-substituents were chosen for their ability to influence the way in which the dications pack in the solid state. We suspect that this packing most likely corresponds to the way in which these molecules aggregate in aqueous solutions.

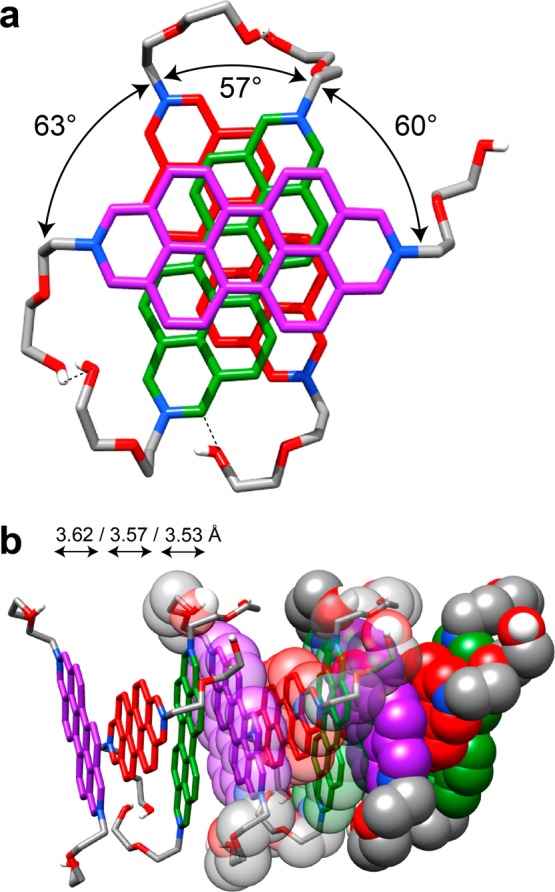

Recently, we reported36 the solid-state structure of the 2,9-dimethyl-DAPP2+ dication 12+, revealing that the dications pack in such a way as to form one-dimensional stacks. In this geometry, the perylene core of one dication is available to take part in π···π interactions with the perylene core of two neighboring dications which stack in a repetitive ABC manner so that the angle of N–N vectors between adjacent dications is approximately 60°, presumably to minimize Coulombic repulsions while maximizing π···π overlaps. Dication 52+ also displays (Figure 2) this particular solid-state packing behavior, where the angles between N–N vectors on the adjacent DAPP2+ dications are 63, 60 and 57°, and the interplanar spacings (centroid-to-centroid distances) are 3.57, 3.62, and 3.53 Å between neighboring perylene cores. In addition to the π···π interactions between these DAPP2+ dications, there are also multiple [C–H···O] interactions between (i) the protons α to the nitrogens and the terminal oxygen atoms in the diethylene glycol chains of adjacent DAPP2+ dications (3.11–3.38 Å), and (ii) the protons α to the nitrogens and the central oxygen atoms in the chains on the same DAPP2+ dication (2.91–3.35 Å). The [O···O] distance (2.76 Å) between terminal hydroxyl groups on adjacent DAPP2+ dications (Figure 2a) also constitutes yet another hydrogen bonding interaction present within the dicationic stacks. This combination of π···π stacking and hydrogen bonding interactions is reminiscent of a similar phenomenon observed57 recently in single-crystals of all-organic materials possessing ferroelectric properties at room temperature.

Figure 2.

Solid-state superstructure of 52+ displaying an ABC-type packing motif along one dimension. (a) Top-down view (tubular representation) of a single ABC stack showing the angles between the N–N vectors of adjacent 52+ dications and multiple [C–H···O] and hydrogen bonding interactions, indicated by dashed lines. (b) Tubular and space-filling representation of three repeating ABC stacks shown with the centroid-to-centroid distances between adjacent dications.

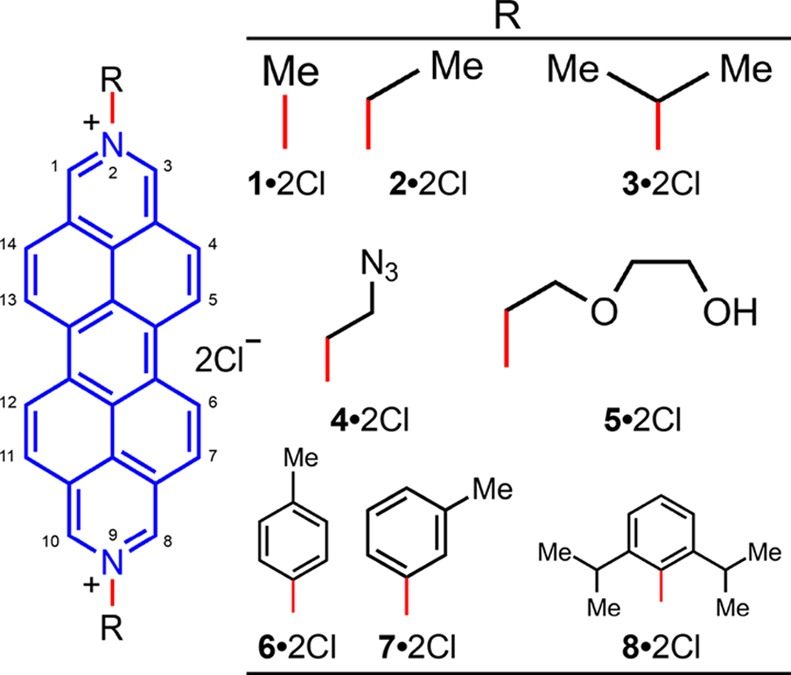

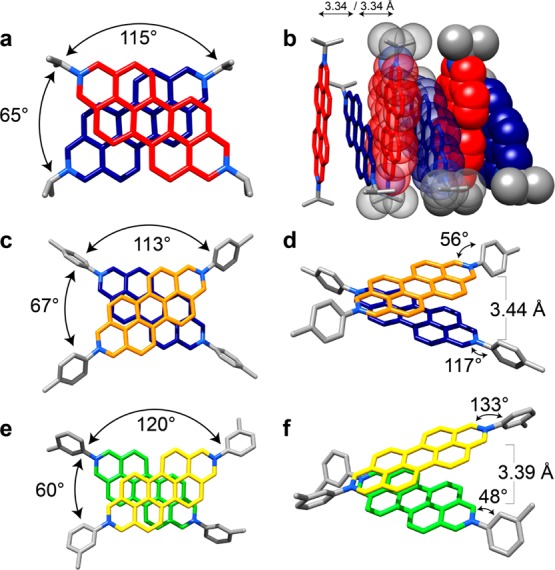

When sterically more bulky substituents are present at the 2 and 9 positions of the DAPP2+ dications, the way in which those dications interact with one another to form one-dimensional stacks in the solid state changes to that of an AB stacking motif, e.g., in the case of 32+, 62+, and 72+, with iPr, p-MeC6H4, and m-MeC6H4 substituents, respectively, the angles (Figure 3a,c,e) between the N–N vectors of adjacent DAPP2+ dications are 114.8, 112.8 and 119.7°, respectively. The presence of even bulkier groups, namely, 2,6-iPr2C6H3, at the 2 and 9 positions of a DAPP2+ dication (82+), imposes steric restrictions which inhibit π···π stacking interactions altogether. The solid-state structure (Figure 4) reveals that the isopropyl groups extend beyond the perylene core of the DAPP2+ dication, thereby blocking access to the perylene core by an adjacent dication. The planes of the 2,6-diisopropylphenyl groups are nearly perpendicular (82°) to the DAPP2+ plane and result in the dications packing in a herringbone-like fashion. The presence of the two 2,6-iPr2C6H3 groups also increases the solubility of the DAPP2+ dication in aqueous and polar organic solvents using chloride or hexafluorophosphate anions, respectively, compared to other groups, e.g., as in the p-MeC6H4 and m-MeC6H4 derivatives, on account of the restricted ability of these dications to aggregate, a phenomenon which is also observed47−52 with the related perylene diimides in organic solvents.

Figure 3.

Tubular (and space-filling) representations of the solid-state superstructures revealing the angle and distance between adjacent dications for 32+ (a and b), 62+ (c and d), and 72+ (e and f). All three dications display an ABAB stacking motif in the solid state as a result of the increased steric interactions provided by the substituents in the 2 and 9 positions of the diazaperopyrenium dication. For the numbering of the positions on the dication, please refer to the general structural formula in Figure 1.

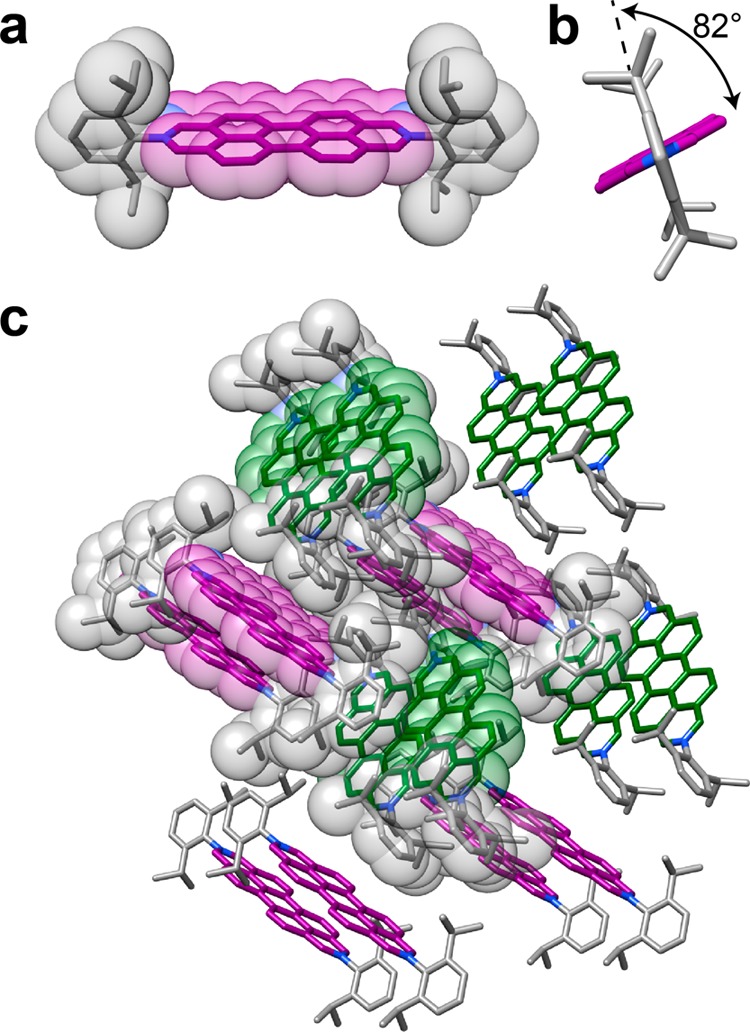

Figure 4.

(a) Space-filling and tubular representations of the solid-state structure of 82+ revealing that the isopropyl groups extend over the perylene core of the dication, inhibiting π···π stacking of these dications along one dimension. (b) View down the N–N vector of a single 82+ dication revealing the angle between the plane of the diazaperopyrenium unit and the 2,6-diisopropylphenyl substituents located in the 2 and 9 positions of the dication. (c) Tubular (and space-filling) representations of the solid-state superstructure of 82+ revealing a herringbone-like packing motif and the absence of any π···π interactions. Purple and green denote dications that are orientated in the same direction.

Given the facts (i) that DNA intercalators are common targets58 for therapeutic development, (ii) that structurally similar pyrenium cations have demonstrated43−45 anticancer activity, and (iii) that 2,9-dimethyl-DAPP2+ (12+) intercalates40,41 ds-DNA, we sought to investigate the therapeutic potential of the range of DAPP2+ dications reported in this communication.

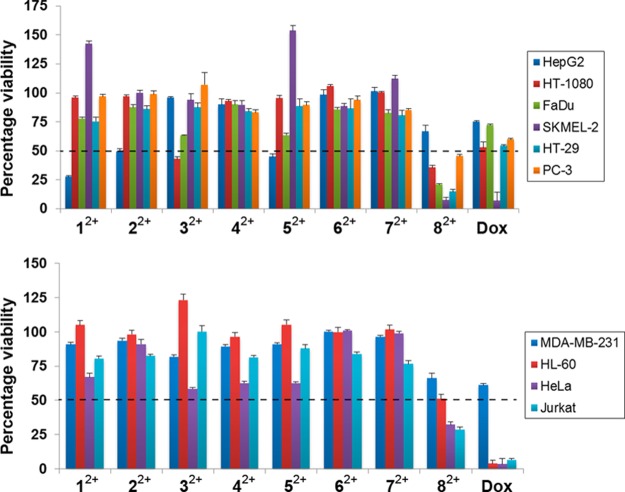

The antiproliferative effects of the dichloride salts of the DAPP2+ dications 12+–82+ were evaluated against 10 cancerous cell lines—HT29 (colon), SKMEL-2 (melanoma), HepG2 (liver carcinoma), Jurkat (lymphoma), Hela (cervical), MDA-MB-231 (breast), PC-3 (prostate), FaDu (squamous cell carcinoma), HT-1080 (fibrosarcoma), and HL60 (leukemia). The antiproliferative screens were performed using a concentration of 10 μM of each of the dichlorides, with doxorubicin plated as a standard for comparison. The results, which are illustrated in Figure 5, are listed (Table S1) in detail in the Supporting Information. A number of the dichlorides resulted (shown as a dotted line in Figure 5) in lower than 50% viability after a 48 h incubation. Notably, the DAPP2+ dications 12+, 22+ and 52+ resulted in less than 50% cell survival, i.e., 27.8 ± 0.8, 49.5 ± 2.3, 44.9 ± 2.5% cell viability, respectively, against HepG2 liver carcinoma cells, a statistically significant difference when compared to cells treated with doxorubicin with a cell viability of 74.9 ± 1.0%. The DAPP2+ dication 32+, which demonstrated a considerable antiproliferative effect (42.9 ± 1.9% cell viability) on HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cells, proved to be more potent than treatment with doxorubicin with a cell viability of 56.3 ± 5.5%. The most remarkable findings from the cell proliferation screen, however, were observed for the 2,9-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)-DAPP2+ dication 82+. The dichloride 8·2Cl exhibited significant potency with less than 50% cell viability, against all but two of the cell lines tested, with the SKMEL-2 cell line having the lowest cell viability (7.2 ± 2.5%) when exposed to 10 μM of 8·2Cl. The data in Table 1 and the histogram illustrated in Figure 5a reveal six cell lines in which 8·2Cl had close to the same, or greater, potency as doxorubicin. These encouraging results prompted us to (i) investigate the anticancer activity of 8·2Cl further by performing a proliferation assay at various concentrations of the salt and (ii) generate dose–response curves. IC50 values were derived from dose–response curves at nine different concentrations. The three cell lines HT-29, SKMEL-2, and FaDu, against which 8·2Cl showed the highest toxicity from the proliferation screen, were tested. The resulting IC50 values are listed in Table 2. Low micromolar efficacies of 12.3 ± 0.2 and 4.81 ± 0.2 μM were observed against SKMEL-2 and FaDu cells, respectively, while submicromolar potency (510 ± 260 nM) was observed with the HT-29 cell line.

Figure 5.

Effect on cell proliferation of each compound 12+–82+ (as their dichlorides) and doxorubicin at 10 μM was evaluated against 10 cancer cell lines. (a) The six cell lines for which 82+ had a similar efficacy to doxorubicin. (b) The four cell lines for which 82+ was not as potent as doxorubicin. All dications were investigated as their chloride salts.

Table 1. Cell Viability Data for Compound 8·2Cl and Doxorubicin for the 10 Cell Lines Tested.

| cell viability (%) |

||

|---|---|---|

| cell line | 8·2Cl | doxorubicin |

| FaDu | 20.6 ± 1.1 | 72.2 ± 0.9 |

| SKMEL-2 | 7.2 ± 2.5 | 6.9 ± 7.3 |

| HT-29 | 14.9 ± 1.7 | 54.3 ± 0.9 |

| HT-1080 | 35.6 ± 1.8 | 56.3 ± 5.5 |

| HepG2 | 66.8 ± 5.2 | 74.9 ± 1.0 |

| HL-60 | 51.1 ± 3.4 | 4.0 ± 2.5 |

| Jurkat | 28.9 ± 1.9 | 6.7 ± 0.9 |

| PC-3 | 45.6 ± 1.2 | 59.7 ± 1.1 |

| HeLa | 32.3 ± 1.8 | 3.9 ± 4.0 |

| MDA-MB-231 | 66.1 ± 3.5 | 61.1 ± 1.3 |

Table 2. IC50 Values Determined from Dose-Response Curves for 8·2Cl against Three Cell Lines.

| cell line | 8·2Cl IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|

| HT-29 | 0.51 ± 0.26 |

| FaDu | 4.81 ± 0.16 |

| SKMEL-2 | 12.32 ± 0.19 |

We hypothesize that it is the propensity of the DAPP2+ salts to self-aggregate and the availability of the perylene core to take part in π···π or hydrophobic interactions which affects the potency of the compounds as cancer therapeutic agents when testing a library of these compounds. We recall that the packing in the solid state of the DAPP2+ dications 12+ through 72+ all show that π···π stacking interactions play a significant role in driving molecular orientation in their crystalline states. It is also reasonable to conclude that a hydrophobic effect operates in aqueous solution. When these π···π intermolecular interactions are inhibited by steric shielding of the diazaperopyrenium cores, the solution-phase molecules more likely exist in a monomeric state or at least as fleeting and small aggregates. This situation is reflected in the crystal packing (Figure 4) of the 82+ dications wherein long-range, repetitive π···π associations between diazaperopyrenium cores are impeded. These salts may be better suited to transitioning across membrane barriers or intercalating more efficiently than the aggregated species, leading to a marked increase in cell growth inhibition, as demonstrated by the higher potency of 8·2Cl relative to the other DAPP2+ salts tested.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments were conducted on 1·2Cl, 3·2Cl, 5·2Cl and 8·2Cl to determine if the different DAPP2+ salts undergo solvent-directed aggregation in solution (see Supporting Information). In aqueous solution, 8·2Cl was observed to form small (50–100 nm) stable aggregates, while 1·2Cl and 3·2Cl were observed to form only large (>200 nm) aggregates that increase in diameter over time. Interestingly, 5·2Cl was not observed to aggregate in deionized water, but aggregated over time in pH 7.2 phosphate-buffered solution. All samples tested in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum resulted in signals greater than 100 nm, giving strong evidence to support the claim that the DAPP2+ aggregation observed in aqueous and pH 7.2 phosphate-buffered solutions extends to the biological medium.

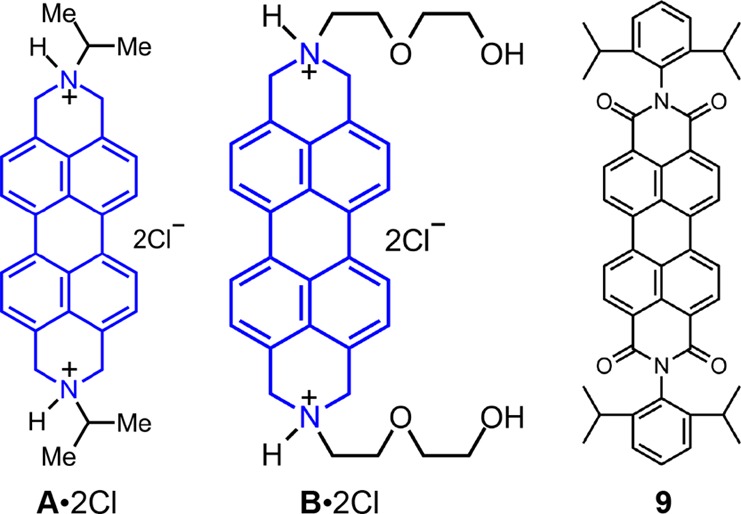

There is evidence, however, to support the belief that the dicationic state of 82+ also plays a significant role in determining the potency and pharmacokinetic behavior observed during the screening against cancer cells. In support of this possibility we prepared compound 9 (Figure 6), namely, N,N-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)perylene-3,4:9,10-bis(dicarboximide), which was also screened against cancer cell lines. Although location of bulky substituents on the terminal nitrogens could prevent aggregation, the presence of the carboximides removes the possibility of the formation of dications. This constitution allowed us to observe the effect of charge on the chemotherapeutic potency, while still maintaining some of the general structural ingredients of 82+. It transpires that the two 2,6-iPr2C6H3 groups in 9 enhance its solubility in Me2SO, by comparison with other perylene diimides with less bulky substituents. Of the 10 cell lines screened, all but one showed cell viability greater than 80%, suggesting that 9 is not as effective a potential chemotherapeutic drug target as 8·2Cl. Compound 9 displayed (Table 3) relatively high potency (26.3 ± 9.5% cell viability) against the HL-60 cell line, and, as such is significantly more effective (51.1 ± 3.4% cell viability) than 82+ for this particular cell line. The positive charge on 82+, as well as on 12+–72+, most likely plays a crucial role in determining the effectiveness of these polyaromatic compounds as chemotherapeutic agents. The charged state could contribute to both the strengthening of the DNA intercalating ability of the DAPP2+ dications as well as to increasing the probability of transition of the drug from the lipophilic membrane into the hydrophilic cytosol or nucleus. However, as we observed with HL-60, where 9 is more cytotoxic than 8·2Cl, there appears to be no universal characteristic associated with these compounds that suggests treatment of all cancer cell lines.

Figure 6.

Structural formulas for compounds A·2Cl, B·2Cl, and 9.

Table 3. Cell Viability Data for A·2Cl, B·2Cl and 9 for the 10 Cell Lines Tested.

| cell viability (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| cell line | A·2Cl | B·2Cla | 9b |

| FaDu | 65.4 ± 2.5 | 79.6 ± 0.6 | 96.5 ± 0.6 |

| SKMEL-2 | 145.7 ± 3.8 | 3.6 ± 11.1 | 106.2 ± 9.9 |

| HT-29 | 28.0 ± 1.2 | 94.4 ± 1.0 | 92.4 ± 3.1 |

| HT-1080 | 64.1 ± 1.9 | 44.7 ± 5.7 | 115.5 ± 1.6 |

| HepG2 | 13.1 ± 11.3 | 55.5 ± 3.3 | 85.8 ± 1.4 |

| HL-60 | 107.5 ± 2.0 | 81.8 ± 5.2 | 26.3 ± 9.5 |

| Jurkat | 8.3 ± 3.5 | 1.9 ± 4.7 | 85.6 ± 1.2 |

| PC-3 | 79.1 ± 0.8 | 48.4 ± 2.2 | 88.2 ± 1.9 |

| HeLa | 82.5 ± 2.3 | 6.2 ± 2.8 | 94.7 ± 1.3 |

| MDA-MB-231 | 56.2 ± 5.7 | 57.6 ± 2.0 | 98.0 ± 0.4 |

Normalized to pure H2O control.

Normalized to pure DMSO control.

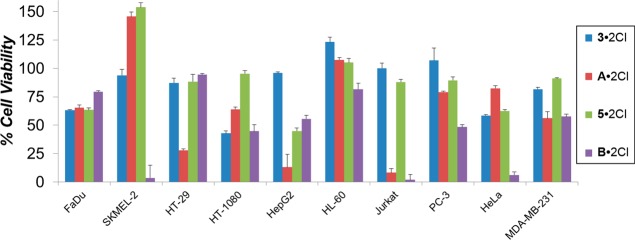

In order to investigate the nature of the structural effects of the DAPP2+ dications in more detail, the degrees of aromaticity in the case of two of the dications were altered. In many drugs, the presence59 of a basic amino group changes their solublities and pharmacodynamics properties, as well as providing some degree of lysosomotropic ability.60−62 The library of structures examined so far in this investigation has focused on a possible correlation between π···π stacking propensity and therapeutic activity. Since failing to oxidize the “deoxygenated perylene diimide” intermediate at the final stage in synthesis leaves us with a protonatable amine derivative, it was of interest to test the therapeutic behavior of the basic amine as well as the change in the aromaticity in these compounds on cell viability. A·2Cl and B·2Cl, derivatives of 3·2Cl and 5·2Cl, respectively, were obtained as a result of not exposing the “deoxygenated perylene diimide” intermediate to the final oxidative dehydrogenation conditions, and thus the terminal heterocyclic rings are no longer aromatic in these structures (Figure 6). Although a comparison of cell viability between the diazaperopyrenium and hexahydroanthradiisoquinoline aromatic salts revealed similar cytotoxicities for most of the cell lines tested, A·2Cl (Figure 7, Table 3) appears to be more cytotoxic than the diazaperopyrenium salt 3·2Cl in the HT-29, HepG2 and Jurkat cell lines. IC50 data for A·2Cl reveal low micromolar efficacy (1.3 ± 0.11 and 8.6 ± 0.17 μM) toward HepG2 and Jurkat cell lines, respectively, and submicromolar efficacy (620 ± 78 nM) against HT-29. Likewise, B·2Cl has greater cytotoxicity in the SKMEL-2, Jurkat, and HeLa cell lines than 5·2Cl, with IC50 data indicating low micromolar efficacy (9.2 ± 7.1, 5.2 ± 0.18, and 1.8 ± 0.08 μM, respectively) against these cell lines. For both compounds, the IC50 values are comparable to those obtained with the doxorubicin controls. The concept of tuning aromaticity in polycyclic aromatic compounds could be a strategy worthy of further investigation for altering the toxicity behavior in this class of compounds.

Figure 7.

Comparison of cell viablilty between compounds 3·2Cl and 5·2Cl and their respective nonoxidized derivatives A·2Cl and B·2Cl. For SKMEL-2, HT-29, HepG2, Jurkat and HeLa cell lines, there is a considerable difference in the potency of the dications based solely on the degree of aromatization.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that a range of DAPP2+ dications as their dichloride salts are potent chemotherapeutic targets. Modifying the nature and size of substituents on the 2 and 9 positions of the DAPP2+ dication allows the potency toward specific cell lines to be tuned. The introduction of sterically demanding substitutents into these positions aids solubility in aqueous media and, in the case of 8·2Cl, increases the potency against the majority of cell lines tested, particularly against HT-29, FaDu and SKMEL-2. Tailoring the aromaticity of the terminal heterocycles in these materials results in significant changes in the potency of the dications toward specific cell lines, particularly SKMEL-2, HepG2, Jurkat and HeLa. This investigation opens up another possible route toward the design and synthesis of new drug candidates for the treatment of cancer. Moreover, the unique spectroscopic properties38−41 of these compounds could be employed to track their intracellular fate as well as to explore their mechanisms of action, in conjunction with photodynamic therapeutic techniques.

Methods

Crystal Growth

Single crystals of suitable quality for single crystal X-ray diffraction were grown by the diffusion of iPr2O vapor into MeCN solutions of 3·2PF6, 6·2PF6, and 7·2PF6. Likewise, good quality single crystals of 5·2PF6 and 8·2PF6 were grown by defusing a mixture of iPr2O and Et2O vapor into MeNO2 and MeCN solutions, respectively.

Crystal Data

3·2PF6: 2(C30H26N2), 4(PF6), C2H3N, orange needles, M = 1449.99, crystal size 0.244 × 0.033 × 0.016 mm, orthorhombic, space group Cmca, a = 6.6904(6), b = 24.950(2) Å, c = 35.310(3) Å, α = β = γ = 90°, V = 5894.1(9) Å3, ρcalc = 1.634, T = 100(2) K, Z = 4, R1(F2 > 2σF2) = 0.0844, wR2 = 0.2037. Out of 7618 reflections a total of 1717 were unique. 5·2PF6: 3(C32H30N2O4), 6(PF6), 2(CH3NO2), orange needles, M = 2511.64, crystal size 0.409 × 0.059 × 0.04 mm, monoclinic, space group Cc, a = 35.4484(13), b = 10.5194(4) Å, c = 29.0669(10) Å, α = γ = 90°, β = 109.864(2)°, V = 10194.0(7) Å3, ρcalc = 1.637, T = 100(2) K, Z = 4, R1(F2 > 2σF2) = 0.0539, wR2 = 0.1372. Out of 24977 reflections a total of 24977 were unique. 6·2PF6: 2(C38H26N2), 4(PF6), 4.33(C2H3N), orange needles, M = 1778.71, crystal size 0.414 × 0.037 × 0.021 mm, tetragonal, space group P4/n, a = b = 34.0574(17) Å, c = 6.9475(5) Å, α = β = γ = 90°, V = 8058.5(10) Å3, ρcalc = 1.466, T = 100.01 K, Z = 4, R1(F2 > 2σF2) = 0.0773, wR2 = 0.1879. Out of 30323 reflections a total of 5798 were unique. 7·2PF6: 2(C38H26N2), 4(PF6), 5(C2H3N), orange needles, M = 1806.36, crystal size 0.203 × 0.031 × 0.027 mm, monoclinic, space group P21/c, a = 7.3021(3), b = 13.6827(5) Å, c = 39.2653(13) Å, α = γ = 90°, β = 95.246(2)°, V = 3906.7(3) Å3, ρcalc = 1.536, T = 100(2) K, Z = 2, R1(F2 > 2σF2) = 0.0700, wR2 = 0.1825. Out of 20840 reflections a total of 5587 were unique. 8·2PF6: C48H46N2, 2(PF6), 2(C2H3N), orange blocks, M = 1022.91, crystal size 0.66 × 0.387 × 0.214 mm, monoclinic, space group P21/c, a = 11.4221(4), b = 13.2531(4) Å, c = 15.8643(5) Å, α = γ = 90°, β = 99.1783(14)°, V = 2370.76(13) Å3, ρcalc = 1.433, T = 100(2) K, Z = 2, R1(F2 > 2σF2) = 0.0474, wR2 = 0.1453. Out of 101338 reflections a total of 11656 were unique. Crystallographic data (excluding structure factors) for the structures reported in this communication have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center as supplementary publication nos. CCDC–1006815, 1006814, 1006817, 1006816, and 1006813, respectively.

Cell Studies

For cell studies, the hexafluorophosphate counterions were changed to chlorides by the addition of n-butyl ammonium chloride to acetonitrile solutions of the bis(hexafluorophosphate)s. The resulting precipitate (the dichloride salt) was then collected and washed with acetonitrile to remove any excess of n-butyl ammonium chloride. The dichloride salts were then solubilized in a Me2SO/H2O mixture (50:50) to afford either 4 mM (1·2Cl, 3·2Cl, 6·2Cl, 7·2Cl and A·2Cl) or 8 mM (compounds 2·2Cl, 4·2Cl, 5·2Cl, 8·2Cl and B·2Cl) solutions, which were subsequently used for cell viability studies. Compound 9 was solubilized in Me2SO to produce an 8 mM solution that was used for cell viability studies. The growth inhibition of various cell lines was determined according to the protocols from the NCI/NIH Developmental Therapeutics Program, and in collaboration with the Northwestern University Developmental Therapeutics Core Facility. Cells were plated in triplicate in 96 well plates. The cells were plated at densities of 40 000 per well in 100 μL for suspended cells (Jurkat and HL-60) and 20 000 per well in 100 μL for adherent cells (HT-29, HT-1080, PC3, MDA-MB-231, FaDu, HepG2, Hela, SKMEL-2). The cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM l-glutamine. Following cell inoculation, the plates were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% air and 100% relative humidity for 24 h.

After 24 h, the time-zero cells were fixed with ice cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (80% for suspended cells and 50% for adherent cells) and washed five times with water. The compounds to be tested were diluted to twice the desired test concentration in complete media containing 50 μg/mL gentamicin. Aliquots of the compounds were added to the cells in a 1:1 volume ratio and the plates were incubated for an additional 48 h. The cells were then fixed using ice-cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (80% for suspended cells and 50% for adherent cells) and washed five times with water.

For the cell growth inhibition studies, the cells were stained by adding 100 μL of Sulphorhodamine B (SRB) solution (0.4% in 1% acetic acid) to each well, followed by incubation for 10 min at room temperature. The unbound dye was removed with five washes with 1% acetic acid, following which the plates were allowed to air-dry. The bound stain was solubilized for absorbance reading by adding 100 μL of 10 mM trizma (2-amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-propanediol) base solution to each well, followed by absorbance reading at 490 nm with an automated plate reader (Synergy H1-M Microplate reader). The cell viability data reported was normalized to cell viability in an H2O/DMSO 50:50 mixture unless otherwise stated. For half maximal inhibitory concentration studies, after fixing 100 μM Cell Titer Glo (Promega) was added to each well for 30 min. The wells were shaken for 2 min, followed by absorbance measurements.

Dynamic Light Scattering

The DAPP2+ salts were dissolved in H2O/Me2SO (1:1, v/v, 500 μL) to imitate the conditions used to introduce the sample to the cell cultures. Either deionized H2O (1.0 mL), pH 7.2 phosphate buffered solution (1.0 mL) or the RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM l-glutamine (1.0 mL) was added to a Disposable Solvent Resistant Micro Cuvette (ZEN0040, Malvern). The DAPP2+ salt solution (10 μL) was then injected into the cuvette. Analyses of the samples were carried out on a Malvern Instruments Inc., Zetasizer Nano ZS. Measurements were taken using a standard operating procedure (SOP) (10 scans at 10 s/scan) for aqueous solutions at 25 °C. All solvents were run as blanks to identify peaks that correlate to the protein additives or possible impurities in solution.

Acknowledgments

This research is part (Project 34-938) of the Joint Center of Excellence in Integrated Nano-Systems (JCIN) at King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST) and Northwestern University (NU). The authors would like to thank both KACST and NU for their continued support of this research. The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number F32GM105403. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This work was supported by the services of the Developmental Therapeutics Core (DTC) of NU, which benefits from philanthropic support of the Robert H. Lurie Cancer Center and the Chemistry of Life Processes Institute. DLS Measurements were performed in the KECKII facility of NUANCE Center at NU, supported by NSF-NSEC, NSF-MRSEC, Keck Foundation, the State of Illinois, and NU. L.S.W. acknowledges support from the International Institute for Nanotechnology (IIN) at NU.

Supporting Information Available

Additional results, materials and general methods, NMR and DLS characterization. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Müller W.; Crothers D. M. Studies of the Binding of Actinomycin and Related Compounds to DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1968, 35, 251–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley L. H. DNA and Its Associated Processes as Targets for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 188–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewey K.; Rowe T.; Yang L.; Halligan B.; Liu L. Adriamycin-Induced DNA Damage Mediated by Mammalian DNA Topoisomerase II. Science 1984, 226, 466–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minford J.; Pommier Y.; Filipski J.; Kohn K. W.; Kerrigan D.; Mattern M.; Michaels S.; Schwartz R.; Zwelling L. A. Isolation of Intercalator-Dependent Protein-Linked DNA Strand Cleavage Activity from Cell Nuclei and Identification as Topoisomerase II. Biochemistry 1986, 25, 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson D.; Hurley L. H. Molecular Struggle for Transcriptional Control. Nat. Med. 1995, 1, 525–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl F. M.; Jovin T. M.; Baehr W.; Holbrook J. J. Ethidium Bromide as a Cooperative Effector of a DNA Structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1972, 69, 3805–3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinen E.; Bassleer R.; Calberg-Bacq C. M.; Desaive C.; Lepoint A. Comparative Study of the Effects of Ethidium Bromide and DNA-Ethidium Bromide Complex on Normal and Cancer Cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1974, 23, 1549–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell H. M.; Reddy B. S.; Bhandary K. K.; Jain S. C.; Sakore T. D.; Seshadri T. P. Conformational Flexibility in DNA Structure as Revealed by Structural Studies of Drug Intercalation and Its Broader Implications in Understanding the Organization of DNA in Chromatin. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 1978, 42, 87–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso A.; Almendral M. J.; Curto Y.; Criado J. J.; Rodríguez E.; Manzano J. L. Determination of the DNA-Binding Characteristics of Ethidium Bromide, Proflavine, and Cisplatin by Flow Injection Analysis: Usefulness in Studies on Antitumor Drugs. Anal. Biochem. 2006, 355, 157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greschner A. A.; Bujold K. E.; Sleiman H. F. Intercalators as Molecular Chaperones in DNA Self-Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11283–11288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescifina A.; Zagni C.; Varrica M. G.; Pistarà V.; Corsaro A. Recent Advances in Small Organic Molecules as DNA Intercalating Agents: Synthesis, Activity, and Modeling. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 74, 95–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman L. S. Structural Considerations in the Interaction of DNA and Acridines. J. Mol. Biol. 1961, 3, 18–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidle S.; Pearl L. H.; Herzyk P.; Berman H. M. A Molecular Model for Proflavine–DNA Intercalation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16, 8999–9016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny W. A. Acridine Derivatives as Chemotherapeutic Agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2002, 9, 1655–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasikala W. D.; Mukherjee A. Molecular Mechanism of Direct Proflavine–DNA Intercalation: Evidence for Drug-Induced Minimum Base-Stacking Penalty Pathway. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 12208–12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S. S.; LaFratta C. N.; Medina A.; Pelse I. Proflavine–DNA Binding Using a Handheld Fluorescence Spectrometer: A Laboratory for Introductory Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2013, 90, 1215–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel Saltiel W. M. Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) Cardiomyopathy—A Critical Review. West. J. Med. 1983, 139, 332–341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodley A.; Liu L. F.; Israel M.; Seshadri R.; Koseki Y.; Giuliani F. C.; Kirschenbaum S.; Silber R.; Potmesil M. DNA Topoisomerase II-Mediated Interaction of Doxorubicin and Daunorubicin Congeners with DNA. Cancer Res. 1989, 49, 5969–5978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb L. A.; Peek M. E.; Zhou F. X.; Bertrand J. A.; VanDerveer D.; Williams L. D. Water Ring Structure at DNA Interfaces: Hydration and Dynamics of DNA-Anthracycline Complexes. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 3649–3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz D. A. A Critical Evaluation of the Mechanisms of Action Proposed for the Antitumor Effects of the Anthracycline Antibiotics Adriamycin and Daunorubicin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 57, 727–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego P.; Corna E.; Cesare M. D.; Gatti L.; Polizzi D.; Pratesi G.; Supino R.; Zunino F. Role of Apoptosis and Apoptosis-Related Genes in Cellular Response and Antitumor Efficacy of Anthracyclines. Curr. Med. Chem. 2001, 8, 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Funes H.; Coronado C. Role of Anthracyclines in the Era of Targeted Therapy. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2007, 7, 56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosell R.; Carles J.; Abad A.; Ribelles N.; Barnadas A.; Benavides A.; Martín M. Phase I Study of Mitonafide in 120 h Continuous Infusion in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Invest. New Drugs 1992, 10, 171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braña M. F.; Ramos A. Naphthalimides as Anticancer Agents: Synthesis and Biological Activity. Curr. Med. Chem.: Anti-Cancer Agents 2001, 1, 237–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez R.; Craig J. B.; Kuhn J. G.; Weiss G. R.; Koeller J.; Phillips J.; Havlin K.; Harman G.; Hardy J.; Melink T. J. Phase I Clinical Investigation of Amonafide. J. Clin. Oncol. 1989, 7, 1351–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braña M. F.; Cacho M.; García M. A.; de Pascual-Teresa B.; Ramos A.; Domínguez M. T.; Pozuelo J. M.; Abradelo C.; Rey-Stolle M. F.; Yuste M.; et al. New Analogues of Amonafide and Elinafide, Containing Aromatic Heterocycles: Synthesis, Antitumor Activity, Molecular Modeling, and DNA Binding Properties. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1391–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braña M. F.; Castellano J. M.; Moran M.; Perez de Vega M. J.; Romerdahl C. R.; Qian X. D.; Bousquet P.; Emling F.; Schlick E.; Keilhauer G. Bis-Naphthalimides: A New Class of Antitumor Agents. Anti-Cancer Drug Des. 1993, 8, 257–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet P. F.; Braña M. F.; Conlon D.; Fitzgerald K. M.; Perron D.; Cocchiaro C.; Miller R.; Moran M.; George J.; Qian X.-D.; et al. Preclinical Evaluation of LU 79553: A Novel Bis-Naphthalimide with Potent Antitumor Activity. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 1176–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalona-Calero M. A.; Eder J. P.; Toppmeyer D. L.; Allen L. F.; Fram R.; Velagapudi R.; Myers M.; Amato A.; Kagen-Hallet K.; Razvillas B.; et al. Phase I and Pharmacokinetic Study of LU79553, a DNA Intercalating Bisnaphthalimide, in Patients With Solid Malignancies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 857–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly C.; Carrasco C.; Joubert A.; Bal C.; Wattez N.; Hildebrand M.-P.; Lansiaux A.; Colson P.; Houssier C.; Cacho M.; et al. Chromophore-Modified Bisnaphthalimides: DNA Recognition, Topoisomerase Inhibition, and Cytotoxic Properties of Two Mono- and Bisfuronaphthalimides. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 4136–4150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Isabella P.; Zunino F.; Capranico G. Base Sequence Determinants of Amonafide Stimulation of Topoisomerase II DNA Cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23, 223–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avendaño C.; Menéndez J. C.. DNA Intercalators and Topoisomerase Inhibitors. In Medicinal Chemistry of Anticancer Drugs; Avendaño C., Menéndez J. C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2008; Chapter 7, pp 199–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ingrassia L.; Lefranc F.; Kiss R.; Mijatovic T. Naphthalimides and Azonafides as Promising Anti-Cancer Agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 1192–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay E. J.; Grier D.; Fingerle R. E.; Reimer R.; Levy R.; Pearce S. W.; Wilson W. D. Interaction Specificity of the Anthracyclines with Deoxyribonucleic Acid. Biochemistry 1976, 15, 2062–2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubař T.; Hanus M.; Ryjáček F.; Hobza P. Binding of Cationic and Neutral Phenanthridine Intercalators to a DNA Oligomer is Controlled by Dispersion Energy: Quantum Chemical Calculations and Molecular Mechanics Simulations. Chem.—Eur. J. 2006, 12, 280–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basuray A. N.; Jacquot de Rouville H.-P.; Hartlieb K. J.; Kikuchi T.; Strutt N. L.; Bruns C. J.; Ambrogio M. W.; Avestro A.-J.; Schneebeli S. T.; Fahrenbach A. C.; et al. The Chameleonic Nature of Diazaperopyrenium Recognition Processes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11872–11877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basuray A. N.; Jacquot de Rouville H.-P.; Hartlieb K. J.; Fahrenbach A. C.; Stoddart J. F. Beyond Perylene Diimides—Diazaperopyrenium Dications as Chameleonic Nanoscale Building Blocks. Chem.—Asian J. 2013, 8, 524–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartlieb K. J.; Basuray A. N.; Ke C.; Sarjeant A. A.; Jacquot de Rouville H.-P.; Kikuchi T.; Forgan R. S.; Kurutz J. W.; Stoddart J. F. Chameleonic Binding of the Dimethyldiazaperopyrenium Dication by Cucurbit[8]uril. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2, 225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Sampath S.; Basuray A. N.; Hartlieb K. J.; Aytun T.; Stupp S. I.; Stoddart J. F. Direct Exfoliation of Graphite to Graphene in Aqueous Media with Diazaperopyrenium Dications. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 2740–2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slama-Schwok A.; Jazwinski J.; Bere A.; Montenay-Garestier T.; Rougee M.; Helene C.; Lehn J. M. Interactions of the Dimethyldiazaperopyrenium Dication with Nucleic Acids. 1. Binding to Nucleic Acid Components and to Single-Stranded Polynucleotides and Photocleavage of Single-Stranded Oligonucleotides. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 3227–3234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slama-Schwok A.; Rougee M.; Ibanez V.; Geacintov N. E.; Montenay-Garestier T.; Lehn J. M.; Helene C. Interactions of the Dimethyldiazaperopyrenium Dication with Nucleic Acids. 2. Binding to Double-Stranded Polynucleotides. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 3234–3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sissi C.; Lucatello L.; Krapcho A. P.; Maloney D. J.; Boxer M. B.; Camarasa M. V.; Pezzoni G.; Menta E.; Palumbo M. Tri-, Tetra- and Heptacyclic Perylene Analogues as New Potential Antineoplastic Agents Based on DNA Telomerase Inhibition. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantanida I.; Palm B. S.; Zinić M.; Schneider H.-J. A New 4,9-Diazapyrenium Intercalator for Single- and Double-Stranded Nucleic Acids: Distinct Differences from Related Diazapyrenium Compounds and Ethidium Bromide. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 2001, 1808–1816. [Google Scholar]

- Piantanida I.; Tomisic V.; Zinić M. 4,9-Diazapyrenium Cations. Synthesis, Physico-Chemical Properties and Dinding of Nucleotides in Water. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 2000, 375–383. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner-Biocić I.; Glavas-Obrovac L.; Karner I.; Piantanida I.; Zinić M.; Pavelić K.; Pavelić J. 4,9-Diazapyrenium Dications Induce Apoptosis in Human Tumor Cells. Anticancer Res. 1996, 16, 3705–3708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacker A. J.; Jazwinski J.; Lehn J.-M.; Wilhelm F. X. Photochemical Cleavage of DNA by 2,7-Diazapyrenium Cations. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1986, 1035–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher A.; Märkle S.; Langhals H. Lösliche Perylen-Fluoreszenzfarbstoffe mit hoher Photostabilität. Chem. Ber. 1982, 115, 2927–2934. [Google Scholar]

- Deyama K.; Tomoda H.; Muramatsu H.; Matsui M. 3,4,9,10-Perylenetetracarboxdiimides Containing Perfluoroalkyl Substituents. Dyes Pigm. 1996, 30, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Langhals H.; Ismael R.; Yürük O. Persistent Fluorescence of Perylene Dyes by Steric Inhibition of Aggregation. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 5435–5441. [Google Scholar]

- Weil T.; Vosch T.; Hofkens J.; Peneva K.; Müllen K. The Rylene Colorant Family—Tailored Nanoemitters for Photonics Research and Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9068–9093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanan C.; Smeigh A. L.; Anthony J. E.; Marks T. J.; Wasielewski M. R. Competition between Singlet Fission and Charge Separation in Solution-Processed Blend Films of 6,13-Bis(triisopropylsilylethynyl)pentacene with Sterically-Encumbered Perylene-3,4:9,10-bis(dicarboximide)s. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 134, 386–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischmann P. D.; Würthner F. Synthesis of a Non-aggregating Bay-Unsubstituted Perylene Bisimide Dye with Latent Bromo Groups for C–C Cross Coupling. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 4674–4677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würthner F. Perylene Bisimide Dyes as Versatile Building Blocks for Functional Supramolecular Architectures. Chem. Commun. 2004, 1564–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhals H. Control of the Interactions in Multichromophores: Novel Concepts. Perylene Bis-imides as Components for Larger Functional Units. Helv. Chim. Acta 2005, 88, 1309–1343. [Google Scholar]

- Jung C.; Ruthardt N.; Lewis R.; Michaelis J.; Sodeik B.; Nolde F.; Peneva K.; Müllen K.; Bräuchle C. Photophysics of New Water-Soluble Terrylenediimide Derivatives and Applications in Biology. ChemPhysChem 2009, 10, 180–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.; Barlow S.; Marder S. R. Perylene-3,4,9,10-tetracarboxylic Acid Diimides: Synthesis, Physical Properties, and Use in Organic Electronics. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 2386–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayi A. S.; Shveyd A. K.; Sue A. C. H.; Szarko J. M.; Rolczynski B. S.; Cao D.; Kennedy T. J.; Sarjeant A. A.; Stern C. L.; Paxton W. F.; et al. Room-Temperature Ferroelectricity in Supramolecular Networks of Charge-Transfer Complexes. Nature 2012, 488, 485–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palchaudhuri R.; Hergenrother P. J. DNA as a Target for Anticancer Compounds: Methods to Determine the Mode of Binding and the Mechanism of Action. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007, 18, 497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman S. D. B.; Funk R. S.; Rajewski R. A.; Krise J. P. Mechanisms of Amine Accumulation in, and Egress from, Lysosomes. Bioanalysis 2009, 1, 1445–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binaschi M.; Bigioni M.; Cipollone A.; Rossi C.; Goso C.; Maggi C. A.; Capranico G.; Animati F. Anthracyclines: Selected New Developments. Curr. Med. Chem.: Anti-Cancer Agents 2001, 1, 113–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y.; Duvvuri M.; Duncan M. B.; Liu J.; Krise J. P. Niemann-Pick C1 Protein Facilitates the Efflux of the Anticancer Drug Daunorubicin from Cells According to a Novel Vesicle-Mediated Pathway. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 316, 242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen V. Y.; Posada M. M.; Blazer L. L.; Zhao T.; Rosania G. R. The Role of the VPS4A-Exosome Pathway in the Intrinsic Egress Route of a DNA-Binding Anticancer Drug. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 1687–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.