To the Editor: Neotropical echinococcosis, caused by polycystic larvae of the tapeworm Echinococcus vogeli and unicystic larvae of E. oligarthrus, is an emerging infection in rural South America (1,2). The parasites are propagated in a predator–prey cycle; the final and intermediate hosts for E. vogeli are bush dogs (Speothos venaticus) and pacas (Cuniculus paca), respectively (1,2). Human infections occur in rural areas and have been reported from several South American countries, mostly Brazil (1–3). Prompted by the recent diagnosis of an E. vogeli infection in a Surinamese patient in the Netherlands (4), we performed a retrospective analysis of all recent echinococcosis cases seen at the Amsterdam Medical Center. We describe molecular and immunohistochemical analyses from another case of E. vogeli infection.

In 2009, a 48-year-old female schoolteacher from Suriname sought care at the Amsterdam Medical Center for recently increasing retrosternal pain. Born in rural Suriname, she moved to the capital city of Paramaribo at 2 years of age. She had worked in the Brokopondo District for 1 year, then worked in urban Morocco, and immigrated to the Netherlands in 1990. Physical and laboratory examination findings were unremarkable. Esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy showed no abnormality. Abdominal ultrasonography and subsequent computed tomography revealed a lesion with solid and liquid components in liver segment 4, considered consistent with a biliary cystadenoma or an echinococcal cyst. Result of an echinococcosis indirect hemagglutination test with E. granulosus hydatid fluid antigen (Fumouze, Levallois-Perret, France) was strongly positive (titer 1:2,560; cutoff 1:160). An uncomplicated central liver resection of an 8-cm polycystic tumor was performed. Microscopic examination of resected tissue found vesicles containing protoscolices surrounded by periodic acid-Schiff–positive membranes.

Based on these findings, the initial diagnosis was cystic echinococcosis caused by E. granulosus, most likely contracted in Morocco. Postoperative treatment was albendazole, 400 mg twice daily for 8 weeks. Findings from a 5-year follow-up examination were unremarkable.

Current histologic reanalysis from archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded surgical specimens revealed laminated layers of the parasites, characteristic of E. multilocularis and E. granulosus larvae (i.e., thin convoluted and very thick areas, respectively). All Echinococcus species can be distinguished by the size and form of their rostellar hooks from protoscolices (1); for protoscolices from the patient reported here, the mean lengths of the small and large hooks were 34 and 43 μm, respectively.

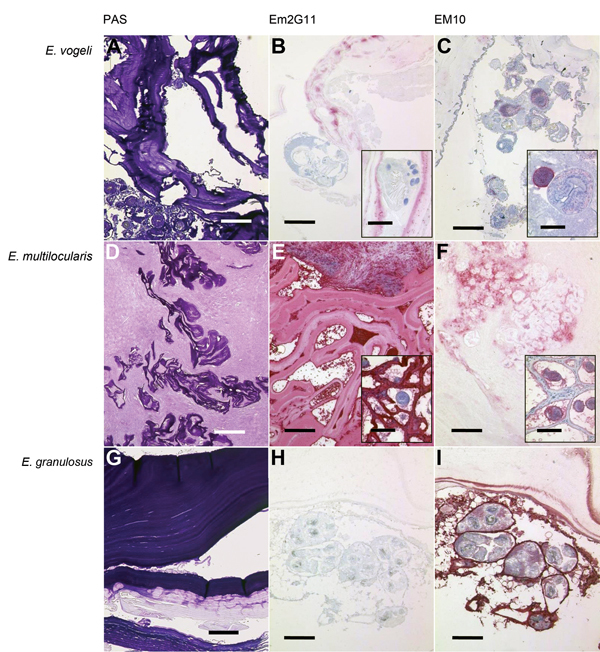

We performed PCRs of the cestode-specific 12S rRNA gene (4) and cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) (5). BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) analysis of the 282-bp and 375-bp amplicons, respectively, showed 100% and 99% homology with E. vogeli (GenBank accession nos. KM588225, KM588226). Phylogenetic modeling based on the cox1 sequence showed that this E. vogeli isolate clustered with isolates from Colombia and Brazil (Technical Appendix). Immunohistochemistry with monoclonal antibody Em2G11 raised against an E. multilocularis laminated layer antigen (Em2) (6) showed a faint and patchy pattern of the laminated layer in the E. vogeli lesion (Figure). Neither the previously described typical complete staining of the laminated layer as found in E. multilocularis larvae nor the entire absence of staining as described for E. granulosus metacestodes (7) was seen in the E. vogeli lesion. The typical staining of small particles of E. multilocularis, characteristically seen adjacent to E. multilocularis (spems) vesicles (7), was completely absent in this specimen. Immunohistochemical examination with a monoclonal antibody against echinococcal cytoskeleton protein EM10 (8) showed staining of the germinal layer and protoscolices of E. multilocularis and E. granulosus larvae but only partial staining of the protoscolices of E. vogeli larvae. According to the proposed staging scheme for polycystic echinococcosis (1), this case was assigned to stage 1.

Figure.

Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining and immunohistochemical analysis of samples from Echinococcus vogeli lesions, with monoclonal antibodies against Em2 and EM10 of E. vogeli (A, B, C), E. multilocularis (D, E, F), and E. granulosus (G, H, I) lesions. Staining was performed on archived tissue from human patients with alveolar and cystic echinococcosis for comparison, and from the patient with E. vogeli infection who immigrated to the Netherlands from Suriname (E. vogeli infection in 2009). B and C insets) Protoscolex, with rostellar hooks clearly visible in inset B. E and F insets) Tissue from infected rodents (laboratory-infected Meriones unguiculatus gerbils) because E. multilocularis lesions in humans only rarely contain protoscolices. A, D, G) PAS-stained sections of the respective echinococcal lesions. Scale bars indicate 500 μm. B, E, H) Lesions with E. vogeli, E. multilocularis, and E. granulosus infection, respectively, stained with the monoclonal Em2G11 antibody against Em2 (for staining details see [7]). E. multilocularis lesions show intense staining, E. granulosus lesions show no staining, and E. vogeli lesions show patchy stains. Scale bars indicate 200 μm; scale bars of the insets indicate 50 μm. C, F, I) Respective lesions stained with antibodies against EM10 (dilution of the primary antibody 1:50; further steps as in Barth et al. [7]). Germinal layer and protoscolices of E. multilocularis and E. granulosus larvae are stained, but the protoscolices of the E. vogeli metacestode are only partly stained. Scale bars indicate 200 μm; scale bars of the insets indicate 50 μm.

Approximately 220 E. vogeli infections have been reported, including 10 from Suriname (1,4,9) and the case reported here. Only 1 case outside echinococcosis-endemic areas has been described in 2013; namely, in a patient from rural Suriname who immigrated to Amsterdam (4). The striking similarities between both cases extended to their clinical presentations.

In a recent immunohistochemistry study (7), antibodies against Em2G11 have shown excellent properties for distinguishing between cystic and alveolar echinococcosis. Although reported to not cross-react with purified laminated layer fractions from in vitro–kept E. vogeli (10), antibodies against Em2G11 exhibited an unusual and possibly discriminatory staining pattern when applied to the E. vogeli lesion from the patient reported here. Antibodies against EM10, which has not before been used for species discrimination on tissue sections, have also shown different staining properties.

Our findings suggest that there may be more undiagnosed cases of polycystic neotropical echinococcoses in immigrants from South America. In retrospect, the treatment (although aimed at E. granulosus) was successful despite the polycystic and proliferative nature of E. vogeli lesions, as indicated by an uneventful prolonged follow-up period for this patient with a well-circumscribed liver lesion. If neotropical echinococcosis had been considered before surgery (on the basis of radiologic features and the patient’s origin), the management would also have included a preoperative and prolonged course of albendazole therapy.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Echinococcus sequences, including 2009 E. vogeli isolate from immigrant from Suriname to the Netherlands.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Klaus Brehm and Matthias Frosch for providing the antibody against EM10 and to Peter Deplazes for providing the Em2G11 antibody against Em2.

T.F.B. was supported by German Research Foundation grant no. DFG KE 282.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Stijnis K, Dijkmans AC, Bart A, Brosens LA, Muntau B, Schoen C, et al. Echinococcus vogeli in immigrant from Suriname to the Netherlands [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Mar [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2103.141205

These authors contributed equally to this article.

Reference

- 1.D’Alessandro A, Rausch RL. New aspects of neotropical polycystic (Echinococcus vogeli) and unicystic (Echinococcus oligarthrus) echinococcosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:380–401. 10.1128/CMR.00050-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tappe D, Stich A, Frosch M. Emergence of polycystic neotropical echinococcosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:292–7. 10.3201/eid1402.070742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knapp J, Chirica M, Simonnet C, Grenouillet F, Bart JM, Sako Y, et al. Echinococcus vogeli infection in a hunter, French Guiana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:2029–31. 10.3201/eid1512.090940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stijnis C, Bart A, Brosens L, Van Gool T, Grobusch M, van Gulik T, et al. First case of Echinococcus vogeli infection imported to the Netherlands, January 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20448 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowles J, Blair D, McManus DP. Genetic variants within the genus Echinococcus identified by mitochondrial DNA sequencing. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;54:165–73. 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90109-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deplazes P, Gottstein B. A monoclonal antibody against Echinococcus multilocularis Em2 antigen. Parasitology. 1991;103:41–9 . 10.1017/S0031182000059278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barth TF, Herrmann TS, Tappe D, Stark L, Gruner B, Buttenschoen K, et al. Sensitive and specific immunohistochemical diagnosis of human alveolar echinococcosis with the monoclonal antibody Em2G11. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Helbig M, Frosch P, Kern P, Frosch M. Serological differentiation between cystic and alveolar echinococcosis by use of recombinant larval antigens. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3211–5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oostburg BF, Vrede MA, Bergen AE. The occurrence of polycystic echinococcosis in Suriname. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2000;94:247–52 . 10.1080/00034980050006429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemphill A, Stettler M, Walker M, Siles-Lucas M, Fink R, Gottstein B. In vitro culture of Echinococcus multilocularis and Echinococcus vogeli metacestodes: studies on the host–parasite interface. Acta Trop. 2003;85:145–55. 10.1016/S0001-706X(02)00220-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Echinococcus sequences, including 2009 E. vogeli isolate from immigrant from Suriname to the Netherlands.