Abstract

In this paper, laser beam resonant interaction with pendant microdroplets that are seeded with a laser dye (Rhodamine 6G (Rh6G)) water solution or oily Vitamin A emulsion with Rhodamine 6G solution in water is investigated through fluorescence spectra analysis. The excitation is made with the second harmonic generated beam emitted by a pulsed Nd:YAG laser system at 532 nm. The pendant microdroplets containing emulsion exhibit an enhanced fluorescence signal. This effect can be explained as being due to the scattering of light by the sub-micrometric drops of oily Vitamin A in emulsion and by the spherical geometry of the pendant droplet. The droplet acts as an optical resonator amplifying the fluorescence signal with the possibility of producing lasing effect. Here, we also investigate how Rhodamine 6G concentration, pumping laser beam energies and number of pumping laser pulses influence the fluorescence behavior. The results can be useful in optical imaging, since they can lead to the use of smaller quantities of fluorescent dyes to obtain results with the same quality.

I. INTRODUCTION

In the last decade, the enhancement of fluorescence was intensely studied,1 in direct connection with the need to identify and/or obtain images of samples that have very small dimensions and consequently a reduced number of fluorophores in their structures. Typical examples imply fluorescence microscopy2–4 applied on biological samples. There are many reports on the fluorescence of a single molecule in which case the fluorescence signal is enhanced by adding in the studied samples local probes that may be metallic nanoparticles with different shapes5,6 such as spherical or rod-like forms. Local probes may have different chemical compositions such as metallic contents (Au, Ag, Pt, Ti, etc.)7–9 or semiconductor structures, for instance silica nanoparticles.10,11 The fluorescence emitted by different fluorophores may be enhanced if proper optical antenna are used.12–14 Amplification of the fluorescence radiation emitted by fluorophores in media which contain nanoparticles may not be used in some cases in applications such as biomedical imaging due to the toxicity of some compounds and to their low biodegradability. At the same time, literature reports show extensive results about evolution and behavior of single cells obtained by studying their fluorescence emitted at excitation with noncoherent and/or laser radiation.15–17

Some organic dyes, such as Rhodamine 6G (Rh6G), are promising candidates to build biocompatible fluorescent systems, due to their good acceptance by biological entities. This is why they are used in a wide range of applications in biology as markers for in vitro or in vivo imaging,3 as well as sensitizers and in particular photosensitizers.18 Drawbacks of the organic dyes are: (1) luminescence is limited when a dye is used in small quantities and (2) self-quenching at high concentrations takes place due to self-absorption of fluorescence radiation produced by the available molecules in dye solutions18 outside emission volume.

The properties of Rh6G in solutions (in water and/or alcohol) are well known, such as absorption and emission (fluorescence excitation and emission spectra), quantum yield, fluorescence lifetime.2 The phosphorescence of Rh6G does not have significant contribution to the energetic balance of the interaction between optical radiation in the visible and the dye molecules at room temperature.19 Rh6G fluorescence quantum yield is very high (>90%) and the energy difference between the first excited singlet state and the first triplet state is lower than 1%.20

Along these lines, we compared the fluorescence emission of Rh6G aqueous solution with that of the emulsion which contains Rh6G in distilled water and oily Vitamin A, obtained by Tessari method. We used oily Vitamin A since, besides its microfluidic properties, it is in itself a medicine with possible benefic effects and in any case, without toxic properties. In principle, it may be of interest to combine the action of a laser beam on a target tissue with that of a medicine which has its properties unaltered and which is introduced in the tissue together with the laser active medium. So, in practical terms one may apply a laser beam emitted by an active medium introduced locally in the tissue for treatment concomitantly with a medicine which has its own curing action on the same tissue.

Both fluorescent systems are generated as pendant microdroplets. In one case, simple droplet containing only Rh6G in distilled water and in the second, compound droplet containing emulsion of Rh6G in water and oily Vitamin A so that in the droplet micro- and nano-metric drops of oil are distributed in water solution of Rh6G. The emitted fluorescence is measured at several Rh6G concentrations, laser pumping energies and different numbers of pumping pulses.

In this study, the use of Rh6G dissolved in distilled water and introduced as part of an emulsion, is proved to be an approach that allows the increase of the Rh6G emitted fluorescence intensity. The effect is due to the scattering of the green pumping light as well as of the fluorescence radiation emitted by the pumped Rh6G molecules. The scattering is induced by the drops of oily Vitamin A in emulsion which have dominantly sub-micrometric dimensions. Moreover, besides the environment of the fluorophores species, the geometry (shape and dimensions) of droplet plays an important role in the signal enhancement. As examples, when the fluorescent system has a spherical geometry, such as a microdroplet, this may act as a microcavity where internal reflection occurs. The droplet acts as an optical resonator which amplifies the fluorescent signal to the stage in which lasing effect is produced.

II. EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

A. Materials and methods

Rh6G in distilled water (Merit water still—W4000) was used to prepare at room temperature the laser dye solutions at five concentrations: 10−5 M, 5 × 10−5 M, 10−4 M, 5 × 10−4 M, and 10−3 M. The Rh6G has been chosen for the high quantum yield in water and for its biocompatibility which makes it suitable for encapsulation in organic nanocarrier.3

The Vitamin A in oil (oily phase in the experiments) is commercially available at the concentration 20 mg/ml.

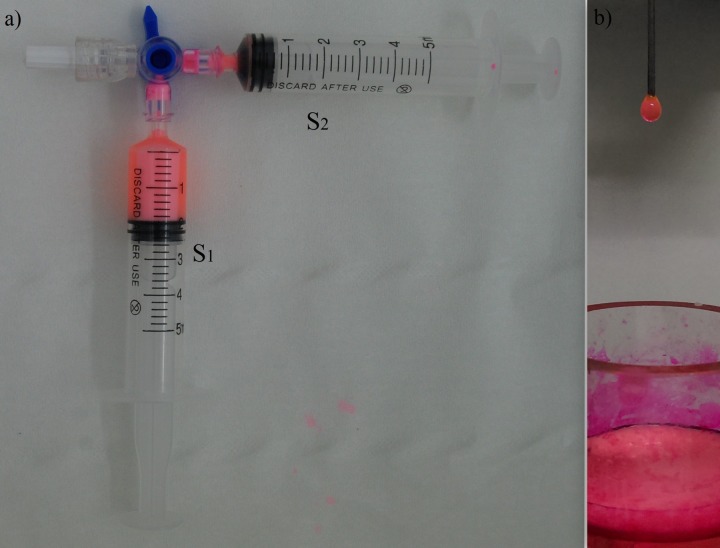

The emulsions were prepared by Tessari method21 described in detail for use in conditions close to ours in Ref. 22. Basically, this method (based on a double syringe system (DSS)) uses two syringes connected through a three-way stopcock (Figure 1). One of the syringes (S1 in Figure 1(a)) contains the aqueous phase (Rh6G in water), while the oily phase is in the other (S2 in Figure 1(a)), therefore eliminating the possibility to have air in the mixture. In Figure 1(a) S1 a small amount of surfactant (Tween 80) was added in order to assure emulsion stability. The two fluids are pumped manually through a three way stopcock in a cyclic mode (in-out), creating the needed high shear rate that leads to droplet breakage. The method provides good results from the point of view of droplet dimensions and mixture quality. In this study, 50 pumping cycles were applied to mix the immiscible fluids and create emulsion. In Figure 1(a), the emulsion obtained in S1 is shown at the end of pumping cycles.

FIG. 1.

DSS used to generate emulsion. (a) Emulsion accumulated in syringe S1 at the end of pumping sequence. (b) Pendant droplet containing emulsion extracted from a crucible where S1 was emptied.

A sample of the obtained emulsion is shown in Figure 1(b) poured in a crucible; out of it, a quantity is sucked using a droplet generator equipped with a capillary-syringe-needle system so that a pendant droplet of emulsion hanging in air is obtained. The ratio of oily Vitamin A/Rh6G solution in water selected for the emulsification measurements was 10%/90% for all the reported experiments, so that emulsions of oil in water were actually studied (observing that oil in this case means Vitamin A in sunflower oil).

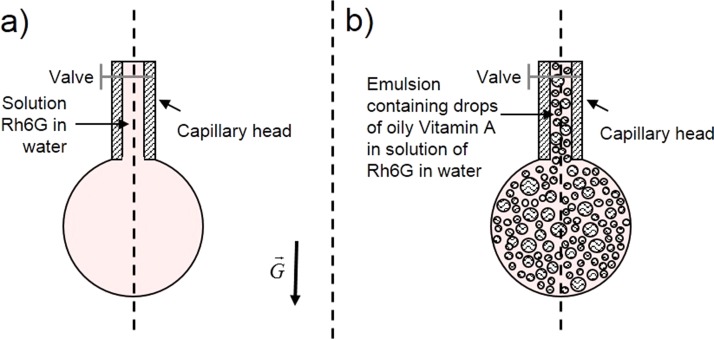

In Figure 2(a), a cartoon representing a droplet of Rh6G in water and in pendant position is shown whereas in Figure 2(b) a droplet of emulsion in pendant position is pictured having drawn its internal droplets structure. The shapes of droplets generated in air are (quasi)spherical. This was assured by choosing that volume of Rh6G water solution or emulsion at which the droplet shape is still spherical, but if we increase this volume further, the droplet is elongated due to its weight (G in Figure 2(a)) to the limit at which it is detached from the needle.

FIG. 2.

Cartoon depicting pendant droplets containing (a) solution of Rh6G in water and (b) emulsion of oily Vitamin A and Rh6G water solution.

In general, this shape depends on the volume of the pumped substance, i.e., the mass of the droplet, the inner diameter of the needle used to generate it, the liquid surface tension and the environment temperature. In our case, droplet volume (both for liquid or emulsion samples) 7 μl, needle inner/outer diameters 0.6 mm/0.91 mm, working temperature 21 °C were used. A spherical shape of the droplet is recommended since the amplification of optical beams inside the droplet (if possible, whispering gallery modes (WGM) generation) is best produced if the emitting medium has a spherical shape.23

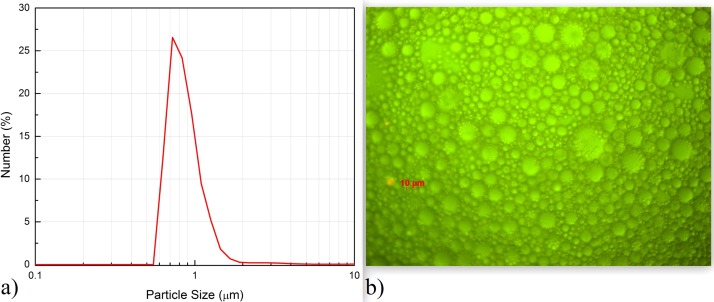

The oily microdroplets average diameter in emulsion is around 0.7 μm, as results from the light scattering measurements shown in Figure 3(a) measured as in Ref. 22. In Figure 3(b), the emulsion structure (10 μm scale) measured with a microscope in reflection mode is shown. One may observe that the oil drops with smaller diameters (below 1 μm) are distributed either randomly in emulsion or associated without coalescing with larger drops. This image justifies the strong light scattering which takes place in the emulsion.

FIG. 3.

Oil microdroplets distribution in emulsion. (a) Oil droplets size distribution obtained by light scattering using Malvern Mastersizer E2000 system. (b) Image of the emulsion structure recorded with a Zeiss Optical Microscope (Imager. Z1m) equipped with axio Cam MRc 5 (HR).

The concentration of Tween 80 was 0.15 v/v% which is lower than its critical micellar concentration—CMC (0.012 mol/m3 ∼0.1536% v/v)24 and allows to consider that no micelles are present in our samples.

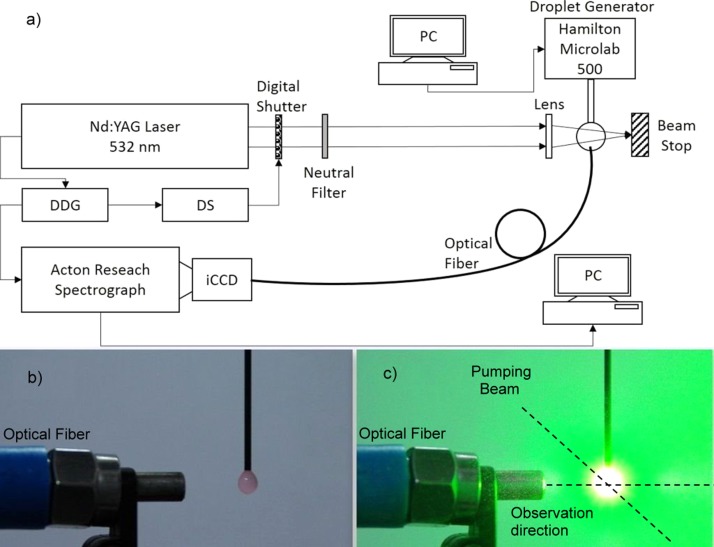

B. Experimental set-up

The experimental set-up is shown in Figure 4. The droplets were generated with a Hamilton MICROLAB 500 Dual Syringe Dispenser and they are pendant in air to a needle. For irradiation, it was used the SHG unfocused beam emitted at 532 nm by a pulsed Nd:YAG laser system (Continuum, Surelite II); the pulse repetition rate was 10 pps. The laser pulse energy used on droplets was either 2.2 mJ or 10 mJ. These two energies were selected in order to evaluate the effect of laser radiation on droplet's content and they were the limits in terms of beam energy within which modifications of the shape of the droplet took not place.25 The laser beam was processed so that it could cover the entire droplet and therefore excite a maximum number of dye molecules within it.

FIG. 4.

Scheme of the experimental set-up. (a) Set-up structure. (b) Pendant droplet of emulsion prior exposure to pumping beam and (c) during exposure.

The fluorescence signal was collected with a VIS optical fiber mounted at 90° with respect to the incident laser beam (along the observation direction in Figure 4(c)) and analyzed with a spectrograph Spectra Pro 750 (Acton Research) coupled with an IMAX 1024 iCCD camera (Princeton Instruments). The measuring chain including the spectrograph detector, the laser system and the Digital Shutter (DS in Figure 4(a)) was synchronized using a Digital Delay Generator (DDG).

In Figure 4(b), a droplet of emulsion is shown in pendant position in air before exposure to the pumping laser beam and in Figure 4(c) the same droplet image is presented taken while one pulsed pumping beam is hitting it.

The fact that the droplet had a stable dimension and shape made it possible to collect its fluorescence emission in the same conditions regardless the pumping energy of the laser beam. For measurements at 10 mJ pumping energy, a Neutral Filter which cuts-off 30% of the fluorescence signal was used to prevent camera saturation. Laser induced fluorescence (LIF) signal acquisition was made on 10 pulses (1 s) for 2.2 mJ laser pumping beam energy for both samples. Each of the fluorescence curves reported in Sec. III represents an average of 10 fluorescence curves, each curve being obtained for one pumping pulse of the same droplet. If the droplet is changed with a new one and the experiment is repeated, the reproduction of the LIF curves is obtained within ±1% error range. The same procedure, with the same error, is used for the measurements at 10 mJ pumping energy in which case LIF has a fast decrease in time; the spectra acquisition was made on 600 pulses (60 s) to evidence the effects of photobleaching on dye solution as well as on emulsion. For one single droplet each LIF curve is an average of 10 curves out of which each is obtained for one pumping pulse, so that during 60 s, 600 curves are obtained, 60 average curves are recorded, and 7 are plotted corresponding to 1 s, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 s, respectively.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

LIF was measured in pendant droplets containing solution of Rh6G in distilled water or mixtures of solution of Rh6G and oily Vitamin A (emulsions) irradiated at 532 nm. The fluorescence spectra are influenced by several parameters such as energy given to the system, solution concentration, and pumping geometry. When such measurements are performed on very small systems with particular shapes, in this case microdroplets, a signal amplification occurs, described usually as WGM.26,27

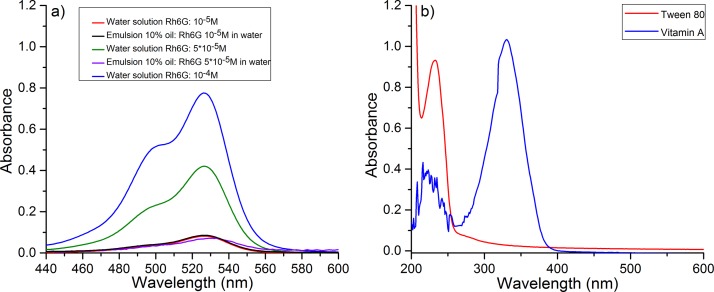

In Figure 5(a), the absorption spectra of bulk (2 ml) solutions of Rh6G in water at several concentrations are shown as well as those of bulk emulsions (2 ml) which contain water Rh6G solution and oily Vitamin A.

FIG. 5.

Absorption spectra of the compounds used in the experiments. (a) Absorption spectra of Rh6G solutions in water and of emulsions produced by mixing water Rh6G solution and Vitamin A. (b) Absorption spectra of Tween 80 and Vitamin A.

For both samples, the absorption spectra have two distinct peaks at concentrations higher than 10−4 M, one at approximately 526 nm and the second at 500 nm. From the optical point of view, the addition of Tween 80 in the mixture has no influence on the samples behavior since this surfactant absorbs in the UV spectral range at about 230 nm, as results from Figure 5(b) and therefore has negligible absorption at 532 nm. Also, the oily Vitamin A has only an absorption peak in UV (Figure 5(b)), which does not influence the optical properties of the mixture at the pumping wavelength. The exposure of Rh6G emulsion at 532 nm does not modify the molecular structures of Tween 80 and Vitamin A in oil. On the other hand, Rh6G is not soluble in oil so that it does not migrate towards the oil-water interface. The surface tension of the oil droplets in surrounding Rh6G aqueous solution is not influenced by exposure to laser radiation at 532 nm, as it resulted from our measurements (data not shown). Since oil and water are not miscible, Vitamin A and Rh6G remain in their own solvents so that they do not interact directly within the emulsion even during exposure to laser pumping beam.

As shown in previous studies,28 the longer wavelength peak corresponds to absorption of free monomers of the dye and the second one occurs due to the coupling between two dye molecules in a dimer. In general, the absorbance of the samples depends of the surrounding medium of the dye. In Figure 5(a), it is higher in solution than emulsion. This may be due to the light scattering in the samples which is higher in emulsion than in simple water solution.

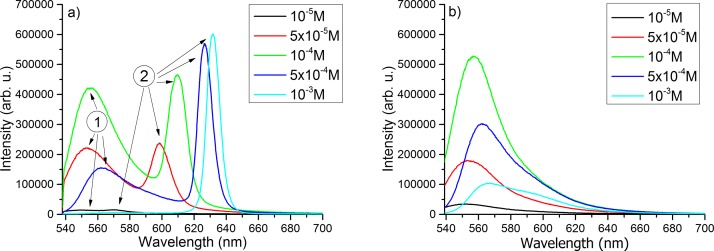

In Figures 6(a) and 6(b), the fluorescence spectra measured on droplets of solutions and emulsions containing Rh6G at different concentrations are shown. In Figure 6(a), the fluorescence emission from a liquid droplet shows two peaks: one at shorter wavelength (arrow 1) specific to fluorescence emission and the second at longer wavelength (arrow 2) showing the build-up of lasing. In Figure 6(b), the fluorescence spectral distribution emitted by a droplet of emulsion shows only one peak and no lasing radiation. This may be due to the fact that 2.2 mJ pumping beam energy is not enough to produce lasing since light scattering in the droplet is significantly higher than in liquid droplet.

FIG. 6.

Laser induced fluorescence emitted by pendant droplets. (a) Lasing and fluorescence spectra obtained from droplet of Rh6G solution in distilled water. (b) Fluorescence spectra obtained in a pendant droplet containing a mixture of Rh6G solution and Oily Vitamin A.

For both cases, the fluorescence intensity increases with Rh6G concentration between 10−5–10−4 M. For concentrations greater than 10−4 M, the reabsorption phenomena become more important and so the self-absorption in the samples, which leads to a decrease of fluorescence signal. Another reason for LIF decrease at higher Rh6G concentrations is the tendency of the organic dyes to form aggregates such as dimers18,28 (see the absorption spectra in Figure 5(a)), which gives a fluorescence self-quenching effect.3

For the spectra of Rh6G in water, due to the spherical shape of the droplet, the lasing emission occurs. A narrow band appears at longer wavelengths,23,29,30 which competes with the broad fluorescence emission band whose intensity is lower than for emulsion. Another characteristics of the fluorescence emission is the red shift of its peaks with the increase of the concentration which is also shown in some literature reports.31,32

For the same concentration of the laser dye, it can be observed that in emulsion the fluorescence intensity is higher than in solution, even if the number of Rh6G molecules in emulsion is smaller with 10% than in solution, due to the utilized ratio oil/solution (10%/90%). The enhancement of emission from small quantities of fluorophores in a microcavity is theoretically treated in Refs. 33 and 34, where one takes into account the geometry of the system. It is known that, by modifying the immediate environment of fluorophores, fluorescence emission is influenced and it can be enhanced or quenched.12,34–36 In our case, the emulsion is generated by adding oily Vitamin A in the aqueous Rh6G solution; this leads to an increase of viscosity. Consequently, the motion of Rh6G molecules in emulsion is inhibited, which leads to the decrease of internal conversion of absorbed laser beam energy and then to higher fluorescence quantum yield similar to the behavior previously observed in alcohol solvents.28,35

This process takes place due to modifications of the spontaneous emission rate and of the fluorescence lifetime. Photobleaching, intermolecular interactions, and angular emission geometry play also a role in emitted fluorescence intensity. In emulsion, an important effect in fluorescence enhancement has the reflecting surface of the microdroplets of oily Vitamin A. This is similar to the optical antenna phenomena.12–14 The presence of reflecting surfaces inside the pendant droplet increases the number of Rh6G excited molecules placed between oil microspheres which induces modification of the local EM field intensity.

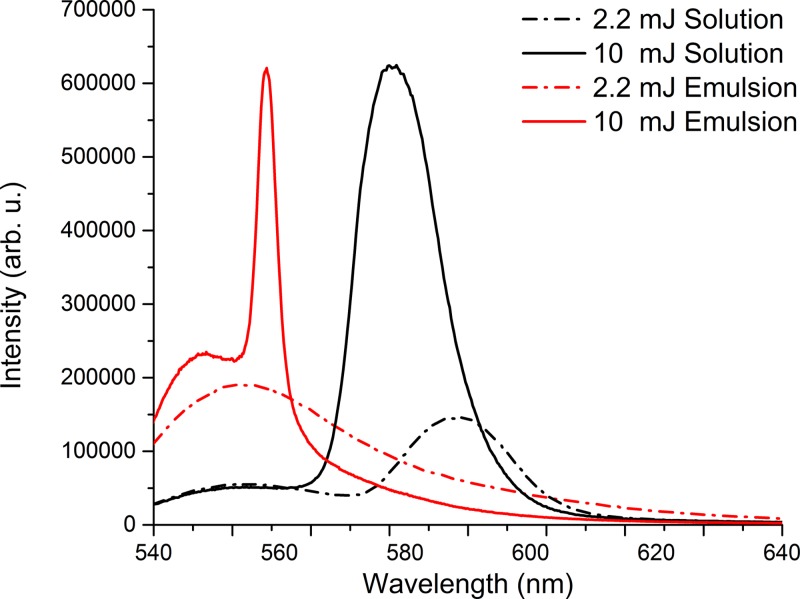

By increasing the energy of the pumping laser beam at 10 mJ per pulse, lasing effect appears in emulsion as well. This can be seen in Figure 7 where the fluorescence spectra emitted by emulsion when pumped at 2.2 mJ and 10 mJ are shown. Lasing peak is produced at 560 nm compared with the one for solution which is placed at 585 nm.

FIG. 7.

Lasing and fluorescence spectra obtained in pendant droplet containing an emulsion of Rh6G in water at 5 × 10−5M and oily Vitamin A for two pumping energies 2.2 mJ and 10 mJ.

The blue- or red-shift of the LIF and lasing band can occur due to the change in polarity of the solvent, or to the formation of fluorescent aggregates of H- and J-type.28,35 The blue-shift of the lasing obtained in emulsion takes place according to Refs. 3 and 36, due to modifications of the polarity of the interfacial medium.

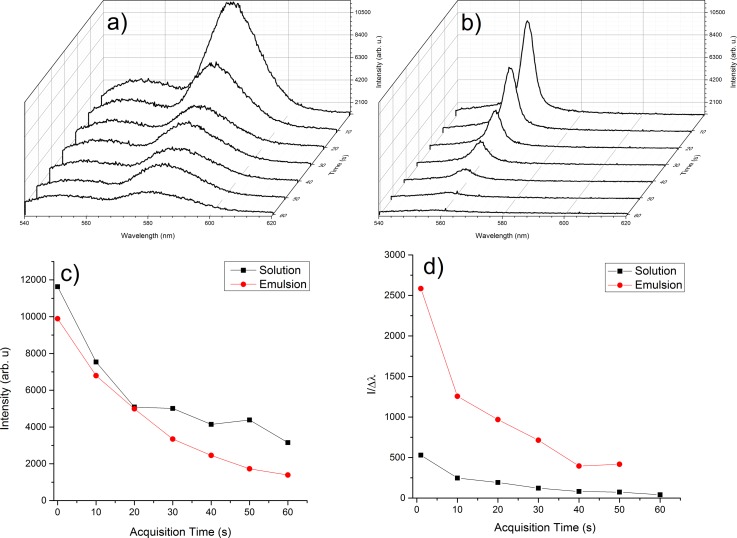

In order to evaluate the time evolution of fluorescence and lasing intensity emitted by a 7 μl droplet containing Rh6G in water or emulsion of Rh6G-water/oily Vitamin A, LIF spectra were measured for a longer irradiation time (60 s) and the results are shown in Table I and Figure 8 using the acquisition procedure described in Experimental set-up section. In Figure 8(a), fluorescence and lasing are measured when emitted by Rh6G solution and in Figure 8(b) the same for emulsion. A first observation is that fluorescence uncoherent radiation is stronger when emitted by liquid droplets than by emulsion while the lasing emitted by emulsion is narrower than in liquid at the same intensity.

TABLE I.

Lasing characteristics function of acquisition/exposure time.

| Dye solution droplet | Emulsion dye droplet | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition Time (s) | Δλ(nm) | Intensity (arb.u.) | (I/Δλ)em | Δλ(nm) | Intensity (arb.u.) | (I/Δλ)liq |

| 1 | 18.69 | 9889 | 529.11 | 4.5 | 11632 | 2584.89 |

| 10 | 27.62 | 6794 | 245.98 | 6 | 7533 | 1255.50 |

| 20 | 26 | 4988 | 191.85 | 5.25 | 5085 | 968.57 |

| 30 | 27.62 | 3344 | 121.07 | 7.02 | 5013 | 714.10 |

| 40 | 30.06 | 2459 | 81.80 | 10.5 | 4143 | 394.57 |

| 50 | 23.63 | 1725 | 73.00 | 10.5 | 4386 | 417.71 |

| 60 | 34.12 | 1392 | 40.80 | 3152 | ||

FIG. 8.

Time evolution of emission spectra obtained for pendant droplets exposed 1 min (600 pumping pulses). Energy per pumping pulse 10 mJ; each spectrum is an average of the fluorescence emission measured for 10 pulses. (a) Pendant droplet containing Rh6G solution (5 × 10−5M) in distilled water. (b) Pendant droplet containing emulsion of Rh6G solution in water (5 × 10−5M) and Oily Vitamin A. (c) Comparison of lasing intensity decreasing in time for both cases. (d) Lasing intensity/lasing bandwidth ratio function of data acquisition time.

Consequently, in Table I for each acquisition time, the bandwidth values of the lased radiation by liquid and emulsion droplets and the ratios, for the same droplets, of the lasing peak intensities to the corresponding bandwidths are presented.

These ratios show that in emulsion the (I/Δλ)em is in average 5 times greater than in liquid droplet, (I/Δλ)liq. This may be also seen in Figure 8(d) where the evolution of I/Δλ for both droplets is plotted with respect to the acquisition time, observing that acquisition time means also exposure time of the respective droplet to the pumping beam.

From Figures 8(a) and 8(b), it results that in both cases a decreasing of fluorescence signal in time takes place. The overall fluorescence intensity is proportional to the fluorescence quantum yield, the absorption coefficient and the pulse energy. Decreasing of fluorescence signal is due to decreasing of the number of fluorophores and to increasing of the number of quenching centers (non-fluorescent species). In our case, photobleaching occurs and destroys Rh6G molecules and the resulting products have radiationless deexcitation channels which lead to the decreasing of fluorescence in time.

In Figure 8(c) it can be observed that, for both droplets, the fluorescence decreases quasi-exponentially in the first 20 s and then the decreasing is slower in solution than in emulsion. This confirms the reports in Refs. 35 and 37, showing that the role of the solvent is significant in fluorescence quenching, due to its viscosity and polarity.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we report results on the emission spectra obtained for pendant droplets containing solutions of Rh6G in distilled water and emulsions of Rh6G solution with oily Vitamin A (20 mg/ml concentration). By varying the dye concentration, we obtained typical fluorescence broad band and a narrow peak assigned to lasing effect in pendant droplets of solutions of Rh6G in distilled water. In emulsion, at the same concentration of Rh6G the fluorescence signal is approximately the same originating from a 10% lower quantity of fluorophores. More than this, the ratios of the lasing peak intensities to the corresponding bandwidths show that in emulsion the (I/Δλ)em is in average 5 times greater than in liquid droplet, (I/Δλ)liq.

We consider that this effect occurs due to the reflecting surfaces of the microdroplets of oily Vitamin A and to the modification of the viscosity in emulsion. These results can open a new area to develop biocompatible fluorescent markers used in optical imaging. By increasing the energy of the pumping laser, lasing effect is also observed in emulsion. In both systems, the peak of the lasing signal depends on the droplet content and this can lead to the generation of tunable microlasers that could be used in medical applications. The microlasers effects could be completed with the effect of other medicines, such as Vitamin A, which may be delivered to the treated tissue without being affected by exposure to the pumping laser beam or the lased radiation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was funded by financing received from CNCS-UEFISCDI by Project Number PN0939/2009, PN-II-ID-PCE-2011-3-0922, COST MP 1205 and COST MP1106. Viorel Nastasa was supported by the strategic Grant POSDRU/159/1.5/S/137750, “Project Doctoral and Postdoctoral Programs support for increased competitiveness in Exact Sciences Research,” co-financed by the European Social Fund within the Sectorial Operational Program Human Resources Development 2007–2013. We acknowledge the assistance extended by Dr. Victor Damian from NILPRP related to the microscopy measurements.

References

- 1.Fort E. and Grésillon S., “ Surface enhanced fluorescence,” J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 41, 013001 (2008). 10.1088/0022-3727/41/1/013001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolmakov K.et al. , “ Red-emitting rhodamine dyes for fluorescence microscopy and nanoscopy,” Chem. Weinh. Bergstr. Ger. 16, 158–166 (2010). 10.1002/chem.200902309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klymchenko A. S.et al. , “ Highly lipophilic fluorescent dyes in nano-emulsions: Towards bright non-leaking nano-droplets,” RSC Adv. 2, 11876–11886 (2012). 10.1039/c2ra21544f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saetzler R. K.et al. , “ Intravital fluorescence microscopy: Impact of light-induced phototoxicity on adhesion of fluorescently labeled leukocytes,” J. Histochem. Cytochem. Off. J. Histochem. Soc. 45, 505–513 (1997). 10.1177/002215549704500403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van de Hulst H. C., Light Scattering by Small Particles ( Dover Publications, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohren C. F. and Huffman D. R., Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles ( Wiley-VCH, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayakawa T., Selvan S. T., and Nogami M., “ Field enhancement effect of small Ag particles on the fluorescence from Eu3+-doped SiO2 glass,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 74, 1513–1515 (1999). 10.1063/1.123600 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strohhöfer C. and Polman A., “ Silver as a sensitizer for erbium,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 1414–1416 (2002). 10.1063/1.1499509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naranjo L. P., de Araújo C. B., Malta O. L., Cruz P. A. S., and Kassab L. R. P., “ Enhancement of Pr3+ luminescence in PbO–GeO2 glasses containing silver nanoparticles,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 241914 (2005). 10.1063/1.2143135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ow H.et al. , “ Bright and stable core–shell fluorescent silica nanoparticles,” Nano Lett. 5, 113–117 (2005). 10.1021/nl0482478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Monte F., Mackenzie J. D., and Levy D., “ Rhodamine fluorescent dimers adsorbed on the porous surface of silica gels,” Langmuir 16, 7377–7382 (2000). 10.1021/la000540+ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kühn S., Håkanson U., Rogobete L., and Sandoghdar V., “ Enhancement of single-molecule fluorescence using a gold nanoparticle as an optical nanoantenna,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 017402 (2006). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.017402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.See http://www.springer.com/chemistry/analytical+chemistry/book/978-0-387-226620 for Radiative Decay Engineering.

- 14.Dragan A. I. and Geddes C. D., “ Metal-enhanced fluorescence: The role of quantum yield, Q0, in enhanced fluorescence,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 093115–093115–4 (2012). 10.1063/1.3692105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernández-Suárez M. and Ting A. Y., “ Fluorescent probes for super-resolution imaging in living cells,” Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 929–943 (2008). 10.1038/nrm2531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao J. A., Yoon Y. J., and Singer R. H., “ Imaging translation in single cells using fluorescent microscopy,” Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a012310 (2012). 10.1101/cshperspect.a012310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas B. L., Matson J. S., DiRita V. J., and Biteen J. S., “ Imaging live cells at the nanometer-scale with single-molecule microscopy: Obstacles and achievements in experiment optimization for microbiology,” Molecules 19, 12116–12149 (2014). 10.3390/molecules190812116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Georges J., Arnaud N., and Parise L., “ Limitations arising from optical saturation in fluorescence and thermal lens spectrometries using pulsed laser excitation: Application to the determination of the fluorescence quantum yield of rhodamine 6G,” Appl. Spectrosc. 50, 1505–1511 (1996). 10.1366/0003702963904511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuznetsov V. A., Kunavin N. I., and Shamraev V. N., “ Spectra and quantum yield of phosphorescence of rhodamine 6G solutions at 77°K,” J. Appl. Spectrosc. 20, 604–607 (1974). 10.1007/BF00607454 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stracke F., Heupel M., and Thiel E., “ Singlet molecular oxygen photosensitized by Rhodamine dyes: Correlation with photophysical properties of the sensitizers,” J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 126, 51–58 (1999). 10.1016/S1010-6030(99)00123-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tessari L., Cavezzi A., and Frullini A., “ Preliminary experience with a new sclerosing foam in the treatment of varicose veins,” Dermatol. Surg. 27, 58–60 (2001). 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2001.00192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nastasa V., Samaras K., Pascu M. L., and Karapantsios T. D., “ Moderately stable emulsions produced by a double syringe method,” Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 460, 321–326 (2014). 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2014.01.044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrett C. G. B., Kaiser W., and Bond W. L., “ Stimulated emission into optical whispering modes of spheres,” Phys. Rev. 124, 1807–1809 (1961). 10.1103/PhysRev.124.1807 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samanta S. and Ghosh P., “ Coalescence of bubbles and stability of foams in aqueous solutions of Tween surfactants,” Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 89, 2344–2355 (2011). 10.1016/j.cherd.2011.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pascu M. L., Popescu G. V., Ticos C. M., and Andrei I. R., “ Unresonant interaction of laser beams with microdroplets,” J. Eur. Opt. Soc. Rapid Publ. 7, 12001 (2012). 10.2971/jeos.2012.12001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanyeri M., Perron R., and Kennedy I. M., “ Lasing droplets in a microfabricated channel,” Opt. Lett. 32, 2529–2531 (2007). 10.1364/OL.32.002529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang S. K. Y., Derda R., Quan Q., Lončar M., and Whitesides G. M., “ Continuously tunable microdroplet-laser in a microfluidic channel,” Opt. Express 19, 2204–2215 (2011). 10.1364/OE.19.002204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sánchez-Valencia J. R., Toudert J., González-García L., González-Elipe A. R., and Barranco A., “ Excitation transfer mechanism along the visible to the Near-IR in rhodamine J-heteroaggregates,” Chem. Commun. 46, 4372–4374 (2010). 10.1039/c0cc00087f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tzeng H.-M., Wall K. F., Long M. B., and Chang R. K., “ Laser emission from individual droplets at wavelengths corresponding to morphology-dependent resonances,” Opt. Lett. 9, 499–501 (1984). 10.1364/OL.9.000499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin H.-B., Eversole J. D., and Campillo A. J., “ Spectral properties of lasing microdroplets,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 9, 43–50 (1992). 10.1364/JOSAB.9.000043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pascu M. L.et al. , “ Spectral properties of some molecular solutions,” Romanian Rep. Phys. 63(Supplement), 1267–1284 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heeg B., DeBarber P. A., and Rumbles G., “ Influence of fluorescence reabsorption and trapping on solid-state optical cooling,” Appl. Opt. 44, 3117–3124 (2005). 10.1364/AO.44.003117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamaguchi T., Kaya T., and Takei H., “ Characterization of cap-shaped silver particles for surface-enhanced fluorescence effects,” Anal. Biochem. 364, 171–179 (2007). 10.1016/j.ab.2007.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tarcha P. J., Desaja-Gonzalez J., Rodriguez-Llorente S., and Aroca R., “ Surface-enhanced fluorescence on SiO2-coated silver island films,” Appl. Spectrosc. 53, 43–48 (1999). 10.1366/0003702991945443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magde D., Rojas G. E., and Seybold P. G., “ Solvent dependence of the fluorescence lifetimes of xanthene dyes,” Photochem. Photobiol. 70, 737–744 (1999). 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1999.tb08277.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brujić J., Song C., Wang P., Briscoe C., Marty G., and Makse H. A., “ Measuring the coordination number and entropy of a 3D jammed emulsion packing by confocal microscopy,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 248001 (2007). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.248001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reisfeld R., Zusman R., Cohen Y., and Eyal M., “ The spectroscopic behaviour of rhodamine 6G in polar and non-polar solvents and in thin glass and PMMA films,” Chem. Phys. Lett. 147, 142–147 (1988). 10.1016/0009-2614(88)85073-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]