Abstract

Objectives

This study was undertaken to evaluate the expression of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9), key regulators of the extracellular matrix composition, in the uterosacral ligaments (USL) of women with pelvic organ prolapse compared with controls.

Methods

Under IRB approval, USL samples were obtained from women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy for stage two or greater pelvic organ prolapse (cases, n=21) and from women without pelvic organ prolapse undergoing vaginal hysterectomy for benign indications (controls, n=19). Hematoxylin and eosin and trichrome staining were performed on the USL sections, and the distribution of smooth muscle and fibrous tissue quantified. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using anti-TGF-β1 and anti-MMP-9 antibodies. The expression of TGF-β1 and MMP-9 was evaluated by the pathologist, who was blinded to all clinical data.

Results

TGF-β1 expression positively correlated with MMP-9 expression (R=0.4, P=0.01). The expression of TGF-β1 and MMP-9 were similar in subjects with pelvic organ prolapse versus controls. There was a significant increase in fibrous tissue (P=0.008), and a corresponding decrease in smooth muscle (P=0.03), associated with increasing age. TGF-β1 expression, but not MMP-9 expression, also significantly increased with age (P=0.02).

Discussion

Although our study uncovered age-related alterations in USL composition and TGF-β1 expression, there was no difference in the expression of TGF-β1 or MMP-9 in the subjects with pelvic organ prolapse versus controls.

Keywords: pelvic organ prolapse, TGF-β1, MMP-9, Uterosacral ligament

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is defined as the herniation of the pelvic organs to or beyond the vaginal walls. Apical POP is the presence of the vaginal apex or cervix prolapsing to or beyond the hymen that is clinically bothersome to the patient [1]. It is a common cause of morbidity and one of the commonest reasons for hysterectomy in menopausal women [2].

Wu and colleagues estimated the number of women who will have symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in the United States in 2050 to be 58.2 million based on population projections from the U.S. Census Bureau from 2010 to 2050 [3].

Presently, the lifetime risk of a woman developing POP is estimated to be approximately 30–50%, with an 11% lifetime risk of undergoing a single operation [4]. More recently Smith and colleagues reported a 19% lifetime risk of operation for Australian women with POP [5]. Based on a large community based retrospective cohort study, factors that increase the risk of pelvic floor dysfunction, including POP, are: older age, postmenopausal status, parity, and being overweight. This was consistent with a large population-based, cross-sectional study from Sweden that found that age and parity were dominant risk factors, but a BMI greater than 26 kg/m2 and a strong family history or personal history of hernias, suggesting weak connective tissue disorders, were independent risk factors for POP [6].

The endopelvic fascia is comprised of collagen, elastin, and smooth muscle. This rich extracellular matrix is thought encase the cardinal-uterosacral ligament, providing key level I support. DeLancey describes three levels of connective tissue support of the vagina when defining pelvic floor anatomy. Level I refers to the apical portion of the posterior vaginal wall, which is suspended and supported primarily by the cardinal-uterosacral ligaments. If level I support is lost, apical POP ensues [7].

At the present time, treatment options are not always curative. It has been cited that the reoperation rate for recurrent POP is as high as 30% [4]. To improve our ability to provide more effective and innovative treatment options, it is imperative that we gain a greater understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease process.

A growing number of studies have shown an association between POP and alterations of the extracellular matrix. It has been suggested that both collagen and elastin production are altered in POP. It is unclear if these alterations are a result of, or rather a cause of pelvic floor dysfunction.

Collagen is a fibrous protein that provides much of the tensile strength to skin, tendon, and bone. There are 19 types of collagen. Type-I and type-III are the two most abundant types in interstitial connective tissue. Type I is found in large amounts in the skin, ligaments, fascia organ capsules, cartilage, and tendons. Type III collagen is found in loose connective tissue. It is thought that Type III collagen is the initial collagen laid down in wound healing and is usually replaced by type I collagen over several months [8]. Both Type I collagen and Type III collagen appear to be essential for pelvic support. Reduced collagen content or alterations in the ratio of collagen types may decrease mechanical strength and predispose an individual to POP. Type I collagen is responsible for mechanical strength in connective tissue, while type III appears to play a role in elasticity.

Collagen is degraded by a family of enzymes called the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). MMPs are a family of zinc and calcium-dependent endopeptidases that assist in maintaining turnover of connective tissue. MMPs are divided into subgroups based on their activity and function. MMP-9 is involved regulating type -1 collagen. MMP-9 cleaves type I, II, IV collagens, and plays an important role in the remodeling of collagenous extracellular matrix. TGF-β1, which down-regulates most MMPs, enhances MMP-9 expression [9].

Transforming growth factor-β 1 (TGF-β1) is a multifunctional cytokine and dominant regulator of multiple extracellular matrix components and enzymes. In addition to TGF-β1, other regulators including tissue-derived inhibitors of metalloproteases (TIMPs) and thrombospondin (TSP-1) are active in maintaining the extracellular matrix. Under normal conditions, a transient increase in TGF-β1 initiates tissue repair after injury. The effects on the synthesis and deposition of extracellular matrix are mediated by the type 1 receptor. Sustained elevations of TGF-β1 have been associated with multiple pathological conditions, such as pulmonary fibrosis, keloid formation, coronary artery restenosis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [10].

Pascual et al illustrated an increase in expression of TGF-β1 in the fascia of inguinal hernias [11]. The pathogenesis of abdominal hernias and POP may be similar, as both conditions result in the loss of fascial support leading to a protrusion or herniation of organs. Recently, Meijerink et al determined that TGF-β1 protein expression was higher in the vaginal wall of women with POP [12].

To our knowledge, there are no published studies that examine the role of TGF-β1 expression and its relation to MMP-9 in the uterosacral ligaments (USL), which provide key level 1 support of pelvic organs. Therefore, we designed this prospective study to investigate the expression of TGF-β1 and MMP-9 in the USL of women with and without POP. We hypothesized that women with POP would have an increase in expression in TGF-β1 and MMP-9 compared to controls. This study is an expansion from our initial pilot study that showed an increase in TGF-β1 expression in subjects with POP, compared with unaffected women [13].

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Yeshiva University, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY.

Forty subjects were recruited for this study. The study group consisted of women with stage 2 or greater POP according to the pelvic organ prolapse quantification system (POP-Q [12], who were undergoing vaginal hysterectomy and modified USL suspension as part of their standard of care for symptomatic POP. Inclusion criteria for the study group included stage 2 or greater prolapse, as assessed by a single physician, and plan for surgery by the same physician to treat the symptomatic prolapse (cases, n=21). Asymptomatic women without evidence of prolapse, who were undergoing vaginal hysterectomy for other benign indications, formed the control group (controls, n= 19). Tissue specimens were obtained at the time of surgery from the USL from all subjects. Exclusion criteria for both study and control groups were uteri greater than 16 week size, as measured by a the single physician, vaginal delivery within the previous one year, use of hormone therapy (topical or oral) within the previous one year, prior or current gynecologic malignancy, and prior reconstructive surgery. The indication for surgery in the control group was menorrhagia (n=17), postmenopausal bleeding (n=1) and carcinoma in-situ (n=1) respectively.

Uterosacral ligament specimens were collected fresh at the time of surgery and assigned a numerical code, which was linked to de-identified clinical data. The samples were fixed in 10% formalin for 24 hours, then paraffin-embedded and sectioned. Using sections stained with H&E and Trichrome, the study pathologist quantified the distribution of smooth muscle and fibrous tissue.

Immunohistochemical staining of the USL sections was performed using anti-TGF-β1 and anti MMP-9 antibodies. Unstained tissue sections were dewaxed and rehydrated in xylene and graded ethanol. The optimal protocols for TGF-β1 and MMP-9 immunohistochemistry were determined by testing primary antibody dilutions and staining conditions on human placental tissue sections. Antigen retrieval was performed using DakoCytomation Target Retrieval Solution, 95c for 30 minutes, endogenous peroxidases were quenched, and sections were incubated with blocking solutions (5% normal donkey serum, 2% bovine serum albumin in TBS) for 1 hour at room temperature. The primary antibodies were a mouse monoclonal antibody to TGF-β1 clone TB21 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) diluted 1:1000 in blocking solution and rabbit monoclonal antibody to MMP-9 (92kDa Collagenase IV) (Labvision, Freeemont, CA) diluted 1:100 in blocking solution. Following an overnight incubation for TGF-β1 and a 30-minute incubation for MMP-9 in a humidified chamber at 4c, slides were washed and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (DAKO Envision +Kit). Detection was performed by application of the freshly prepared 3,3’-Diaminobenzdine chromagen solution for 35 seconds for TGF-β1 and 3 minutes for MMP-9. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and cover slipped using Distyrine-Plasticizer-Xylene (DPX, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). For each slide, a negative control was performed, for which the procedures was carried out as stated above, except the primary antibody was omitted.

Immunohistochemical staining was evaluated by a pathologist who was blinded to the clinical data. The staining for TGF-β1 and MMP-9 of the fibrous tissue, smooth muscle and the section in its entirety (global) were quantified at 100× magnification. Global scores were quantified independently from scores on each individual component. Components such as vessels and endothelial cells were not analyzed. For each sample, intensity of TGF-β1 expression (low(1), high(2)) and the area of positive staining (1–100%) was assigned by the study pathologist. Evaluation of MMP-9 expression was done similarly, except that intensity was categorized as low (1), intermediate (2), and high (3). The H-scores for both TGF-β1 and MMP-9 were calculated by multiplying the intensity by the area of positive staining.

Comparisons were done using two-sample t-tests, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and Fisher’s exact tests for mean, median and proportions respectively. Correlation analysis was analyzed using Pearson test for continuous variables. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Forty women were included in the study: 21 with POP and 19 controls. The clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The mean age, race and postmenopausal status of the cases compared to the controls reached statistical significance. The indications for surgery for the nineteen controls were menorrhagia (n=17), persistent postmenopausal bleeding (n=1) and carcinoma in-situ (n=1) respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Study Population (Bivariate Analysis)

| Variable | Case (N = 21) |

Control (N = 19) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD) | 59.6 (9.6) | 46.1 (9.6) | 1.15 (1.05–1.25) | <0.0001 | |

| Parity, Median (Range) | 3 (0–11) | 2 (0–4) | 1.59 (0.94–2.71) | 0.0923 | |

| Race, No. (%) | 0.0073 | ||||

| White | 3 (15) | 6 (32) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Hispanic | 13 (65) | 3 (16) | 8.67 (1.34–56.23) | ||

| Black | 4 (20) | 10 (53) | 0.80 (0.13–4.87) | ||

| BMI, Mean (SD) | 28.9 (5.2) | 29.6 (4.8) | 0.97 (0.85–1.11) | 0.6626 | |

| Tobacco, No. (%) | 0.0848 | ||||

| None | 20 (95) | 14 (74) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Current/Past | 1 (5) | 5 (26) | 0.14 (0.02–1.33) | ||

| Menopause, No. (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Pre | 4 (19) | 17 (89) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Post | 17 (81) | 2 (11) | 36.13 (5.82–224.22) | ||

By two-sample t-test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and Fisher’s exact test for mean, median, and proportions respectively.

The USL composition and ECM markers of prolapse cases were compared to control subjects (Table 2). Evaluation of the hematoxylin and eosin and Trichrome stained sections was done to determine the percent area of smooth muscle and fibrous tissue of each USL specimen. Similar USL composition was observed in the case and controls. Comparison of TGF-β1 and MMP-9 H-scores showed no difference between the cases and control groups. Age-adjusted analysis of the data was performed which did not significantly alter the results (Table 3).

Table 2.

H&E (smooth muscle), Trichrome (fibrous), TGF-β1, MMP-9 expression in Control subjects and Prolapse cases

| Variable | Case (N = 21) |

Control (N = 19) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H and E % area of smooth muscle Mean (SD) | 35.5 (23.8) | 44.8 (33.6) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.3167 |

| Trichrome %, area of fibrous tissue Mean (SD) | 65.0 (24.2) | 52.8 (32.8) | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.1912 |

| TGF-β1 Fibrous H-score, Mean (SD) | 177.6 (41.2) | 157.9 (56.9) | 1.008 (0.995–1.022) | 0.2139 |

| TGF-β1 Muscle H-score, Mean (SD) | 127.6 (64.2) | 108.8 (61.7) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.3674 |

| TGF-β1 Global H-score, Mean (SD) | 150.9 (61.0) | 141.1 (63.8) | 1.003 (0.992–1.013) | 0.6225 |

| MMP-9 Fibrous H-score, Mean (SD) | 163.3 (114.0) | 171.6 (111.5) | 0.999 (0.994–1.005) | 0.8186 |

| MMP-9 Muscle H-score, Mean (SD) | 82.9 (80.8) | 81.9 (93.5) | 1.000 (0.992–1.009) | 0.9747 |

| MMP-9 Global H-score, Mean (SD) | 114.8 (112.1) | 103.0 (111.1) | 1.001 (0.995–1.007) | 0.7600 |

By two-sample t-test

Table 3.

Age-Adjusted Analysis

| Variable | Case* (N = 21) |

Control (N = 19) |

P-value** |

|---|---|---|---|

| H and E % area of smooth muscle Mean (SE) | 50.2 (8.4) | 44.8 (7.7) | 0.6381 |

| Trichrome %, area of fibrous tissue Mean (SE) | 49.9 (8.4) | 52.8 (7.7) | 0.7985 |

| TGF-β1 Fibrous H-score, Mean (SE) | 83.7 (24.3) | 108.8 (15.0) | 0.3775 |

| TGF-β1 Muscle H-score, Mean (SE) | 152.2 (14.6) | 157.9 (13.1) | 0.7729 |

| TGF-β1 Global H-score, Mean (SE) | 97.1 (18.8) | 141.1 (14.6) | 0.0656 |

| MMP-9 Fibrous H-score, Mean (SE) | 122.1 (42.9) | 171.6 (25.6) | 0.3216 |

The means given for the case column were age-adjusted means with the control ages as reference.

By two-sample t-test

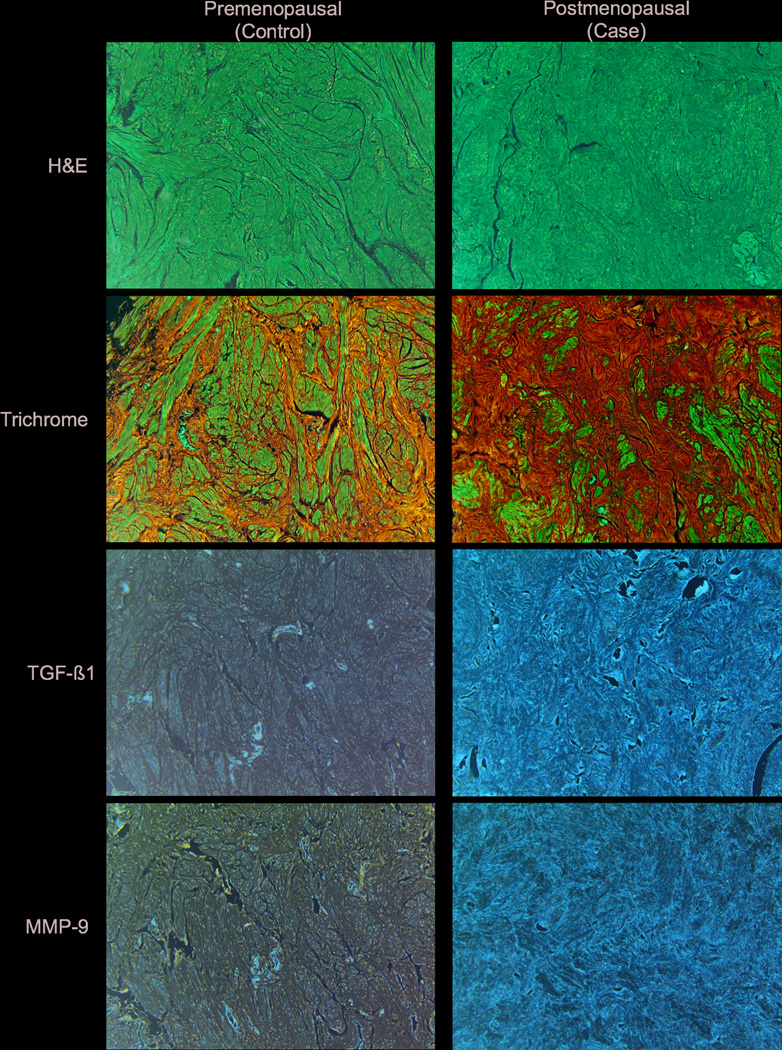

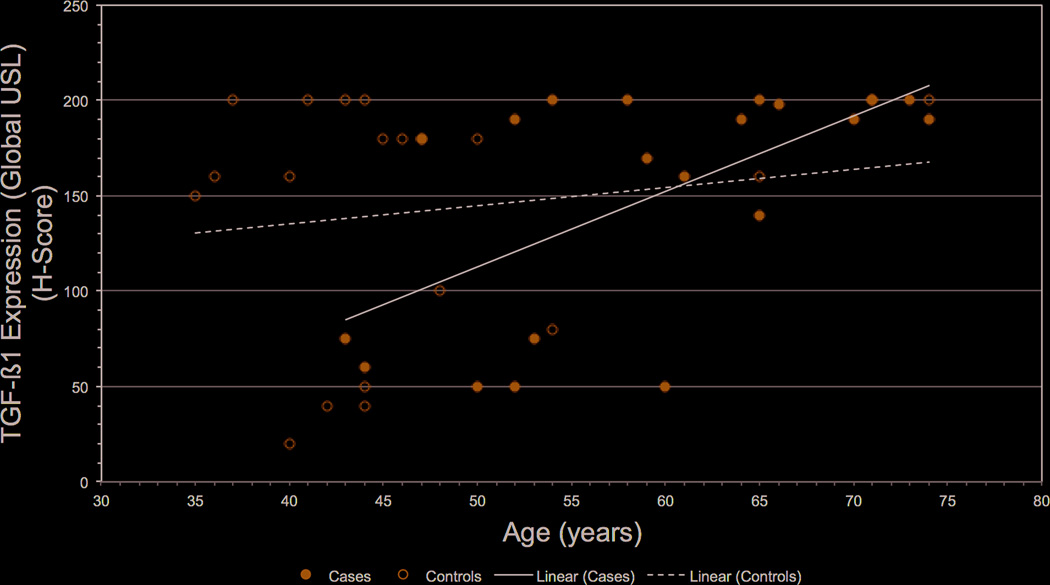

The relationship of age with USL composition, TGF-β1 and MMP-9 was examined (Table 4). We observed a significant decrease in smooth muscle (R=-0.87 (±0.37), P=0.0256) and a significant increase in fibrous tissue (R=1.03 (±0.37), P=0.0082) with higher age. Interestingly, the global USL score showed a significant increase in TGF-β1 expression in relation to age (R=1.91 (±0.80), P=0.0218), however MMP-9 expression did not. Figure 1 shows representative sections of H&E, Trichrome, TGF-β1 and MMP-9 staining in the USL of a premenopausal control and postmenopausal case. Figure 2 shows a scatter plot with trend lines representing the increased expression of TGF-β1 with age. Shown in the scatter plot, in younger women, TGF-β1 expression in USL ranges from extremely low to very high, while in older women >60 year-old exclusively high TGF-β1 expression in USL tissue was seen, regardless of presence or absence of POP.

Table 4.

Effect of age on the uterosacral ligament (USL) composition, TGF-β1 and MMP-9 expression

| Slope (SE) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| H and E % area of smooth muscle | −0.87 (0.37) | 0.0256 |

| Trichrome %, area of fibrous tissue | 1.03 (0.37) | 0.0082 |

| TGF-β1 Fibrous H-score | 1.30 (0.66) | 0.0542 |

| TGF-β1 Muscle H-score | 1.68 (0.88) | 0.0654 |

| TGF-β1 Global H-score | 1.91 (0.80) | 0.0218 |

| MMP-9 Fibrous H-score | −0.49 (0.57) | 0.7582 |

| MMP-9 Muscle H-score | 1.04 (1.31) | 0.4347 |

| MMP-9 Global H-score | 1.24 (1.68) | 0.4673 |

Figure 1.

Representative sections of a USL from a premenopausal (Control) and postmenopausal (Case) patient are shown. The trichrome illustrates the increased fibrous tissue and decreased smooth muscle in the postmenopausal patient compared to the premenopausal patient. In this postmenopausal patient, both TGF-β1 and MMP-9 were highly expressed in the USL as shown by immunohistochemistry.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of TGF-β1 expression in the USL versus age. In younger women, greater variability in expression was observed, while in all women >60 years old high TGF-β1 USL expression was noted. The lines depict the regression line fit by least squares of Cases and Controls.

Correlation analysis was performed to understand the potential relationship of TGF-β1 and MMP-9 expression with the smooth muscle and fibrous tissue composition of the USL (Table 5). No correlation between TGF-β1 and USL composition was observed. Global TGF-β1 expression correlated strongly with fibrous (R=0.83, P<0.0001) and smooth muscle TGF-β1 expression (R=0.78, P<0.0001), indicating that its expression in the different tissue compartments may be coordinately regulated. TGF-β1 expression was also positively correlated with fibrous MMP-9 expression (R=0.4, P=0.0103), consistent with a role of TGF-β1 as a regulator of MMP-9 expression. MMP-9 expression was generally more prominent in the fibrous area than in muscle tissue, although the expression scores in either tissue compartment correlated highly with the global MMP-9 score (Table 6).

Table 5.

Relationship (Pearson R-value) of TGF-β1 expression, USL composition, and MMP-9 expression

| Correlation (P-value) | TGF-β1 Fibrous H-Score |

TGF-β1 Muscle H-Score |

TGF-β1 Global H-Score |

Smooth Muscle Composition of Global USL |

Fibrous Tissue Composition of Global USL |

MMP-9 Fibrous H-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β1 Fibrous H-Score | 1 (n.a.) | 0.63 (<0.0001) | 0.83 (<0.0001) | 0.05 (0.7418) | −0.07 (0.6624) | 0.52 (0.0007) |

| TGF-β1 Muscle H-Score | 0.63 (<0.0001) | 1 (n.a.) | 0.78 (<0.0001) | −0.03 (0.84) | 0.03 (0.86) | 0.4 (0.0121) |

| TGF-β1 Global H-Score | 0.83 (<0.0001) | 0.78 (<0.0001) | 1 (n.a.) | −0.24 (0.14) | 0.22 (0.18) | 0.4 (0.0103) |

n.a. = not applicable

Table 6.

Relationship (Pearson R-value) of MMP-9 expression

| Correlation (P-value) | MMP-9 Fibrous H- score |

MMP-9 Muscle H-score |

MMP-9 Global H-score |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMP-9 Fibrous H-score | 1 (n.a) | 0.52 (0.0031) | 0.73 (<.0001) |

| MMP-9 Muscle H-score | 0.52 (0.0031) | 1 (n.a.) | 0.81 (<.0001) |

| MMP-9 Global H-score | 0.73 (<.0001) | 0.81 (<.0001) | 1 (n.a.) |

n.a. = not applicable

A post-hoc power analysis was performed which calculated the power to detect a 50% difference in fibrous and global TGF-β1 expression between POP and controls is 0.95 and 0.83, respectively, at significance level of 0.05, while the power to detect a 50% difference in fibrous MMP-9 expression between POP and controls is 0.95 at a significance level of 0.05.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first evaluation of TGF-β1 expression in the USL of women with POP. Our findings show an apparent relationship of aging with TGF-β1 expression and altered USL composition. However, no significant differences were observed when comparing prolapse cases with unaffected controls.

We chose to examine the presence of TGF-β1 and MMP-9 expression in the uterosacral ligaments of subjects with POP and unaffected controls because of their important role in the remodeling of the extracellular matrix. Previous studies in human and mouse models have shown alterations in the extracellular matrix leading to the development of POP. Several studies have shown a decrease in the ratio of type -I to type-III collagen in the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments of patients with prolapse [14, 15]. This suggests that women with POP have an increase in extracellular matrix enzymes activity causing a deleterious effect on collagen synthesis, leading to an increase in the weaker type-III collagen and a decrease in the stronger, type-I collagen.

Studies on the role of MMPs have resulted in divergent findings [16, 17]. Dviri et al showed an increase in both MMP-1 and MMP-9 expression in uterosacral ligaments in women with POP [18]. Conversely, Phillips et al showed no difference in expression of MMP-9 in uterosacral ligaments in women with POP compared to controls [19].

The few studies that have looked at TGF-β1 in POP have shown somewhat contradictory results as Meijerink et al showed a positive correlation between TGF-β1 expression and POP in the vaginal wall [12], whereas Qi et al found a negative correlation between TGF-β1 expression and POP in the pubocervical fascia tissue [20]. Based on these studies, tissue expression of TGF-β1 could be discordant in different areas of the genital tract. We chose to analyze the USL since it provides level I support which, when lost, results in apical prolapse.

TGF-β1 has unique and widespread actions in the remodeling of the extracellular matrix, and is critical in tissue integrity. It also acts as potent regulator of repair, coordinating or suppressing the actions of other cytokines [21]. There are several studies from the oncology literature that illustrate a role of TGF-β1 in the activity of MMP in degrading collagen and elastin. Kim et al reported that TGF-β1 up regulates MMP-2 and MMP-9 in human breast epithelial cells [22]. In this study, we evaluated MMP-9 as one downstream effector of TGF-β1, although other factors such as elastin may play a role in POP. We believe that optimal evaluation of elastin requires specialized approaches that could be done in future studies [23].

Strengths of this study include its novelty and prospective study design with molecular study of supportive tissues (USL) relevant to POP. Limitations of the study include that we were unable to age-match the controls to the subjects. This was in part due our inclusion and exclusion criteria and the reality that the majority of elderly women undergo vaginal hysterectomy for POP versus other benign gynecological conditions. Age-adjusted analysis of the data was performed which did not alter our results, suggesting that controlling for age be unlikely to significantly impact the results of the study. Despite the relatively small sample size, the study was well powered to detect a 50% difference in TGF-β1 or MMP-9 expression between POP and controls.

Interestingly, we observed a statistically significant increase in TGF-β1 expression with age, regardless of prolapse. In addition, our study illustrated an increase in fibrous tissue and a decrease in smooth muscle with age. Thus, we have for the first time identified and characterized age-related changes of the extracellular matrix composition and in TGF-β1 expression that could be relevant to the clinical manifestations of POP. However, there was no difference in the expression of TGF-β1 and MMP-9 in the subjects with prolapse versus controls. The similar expression in cases and controls suggest that TGF-β1 and MMP-9 may not be major determinants for developing prolapse.

Pelvic organ prolapse is a common cause of morbidity in women and is associated with high rates of surgical intervention, recurrence, and reoperation. As the prevalence of this condition increases with the rapid growth in the aging population, further understanding of the biological basis of prolapse is needed to provide a basis for the development of novel interventions.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the use of the Albert Einstein Cancer Center Shared Resources (Histology and Comparative Pathology Core), supported by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support grant P30CA013330.

Financial support: NCI-NICHD (K12 HD00849) and American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, through the Reproductive Scientist Development Program award to GSH.

Bibliography

- 1.Swift S. Pelvic organ prolapse: is it time to define it? Int Urogynecol J. 2005;16:425–427. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1372-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilcox LS, Koonin LM, Pokras R, et al. Hysterectomy in the United States, 1988–1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:549–555. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. Women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1278–1283. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2ce96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501–506. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith FJ, Holman CDJ, Moorin RE, Tsokos N. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1096–1100. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f73729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miedel A, Tegerstedt G, Mæhle-Schmidt M, et al. Nonobstetric Risk Factors for Symptomatic Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1089. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a11a85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeLancey JOL. Standing Anatomy of the Pelvic Floor. Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery. 1996;2:260. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu M-P. Regulation of extracellular matrix remodeling associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Medicine. 2010;2:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yong VW, Krekoski CA, Forsyth PA, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases and diseases of the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:75–80. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson MS, Wynn TA. Pulmonary fibrosis: pathogenesis, etiology and regulation. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2:103–121. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascual G, Corrales C, Gómez-Gil V, et al. TGF-beta1 overexpression in the transversalis fascia of patients with direct inguinal hernia. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:516–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meijerink AM, van Rijssel RH, van der Linden PJQ. Tissue composition of the vaginal wall in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2013;75:21–27. doi: 10.1159/000341709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuckerwise L, Banks E, Zhu C, et al. Transforming Growth Factor-β1 Overexpression in Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Journal of Pelvic Medicine and Surgery. 2009;15:231–402. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ewies AA, Azzawi Al F, Thompson J. Changes in extracellular matrix proteins in the cardinal ligaments of post-menopausal women with or without prolapse: a computerized immunohistomorphometric analysis. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2189–2195. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabriel B, Denschlag D, Göbel H, et al. Uterosacral ligament in postmenopausal women with or without pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2005;16:475–479. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabriel B, Watermann D, Hancke K, et al. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinase 2 in uterosacral ligaments is associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2005;17:478–482. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-0045-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang C-C, Huang H-Y, Tseng L-H, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1, TIMP-2 and TIMP-3) in women with uterine prolapse but without urinary incontinence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;153:94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dviri M, Leron E, Dreiher J, et al. Increased matrix metalloproteinases-1,-9 in the uterosacral ligaments and vaginal tissue from women with pelvic organ prolapse. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2011;156:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips CH, Anthony F, Benyon C, Monga AK. Urogynaecology: Collagen metabolism in the uterosacral ligaments and vaginal skin of women with uterine prolapse. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2005;113:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qi X-Y, Hong L, Guo F-Q, et al. Expression of transforming growth factor-beta 1 and connective tissue growth factor in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Saudi Med J. 2011;32:474–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Border WA, Noble NA. Transforming growth factor beta in tissue fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1286–1292. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411103311907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim E-S, Kim M-S, Moon A. TGF-β-induced upregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 depends on p38 MAPK, but not ERK signaling in MCF10A human breast epithelial cells. Int J Oncol. 2004;25:1375–1382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Downing KT, Billah M, Raparia E, et al. The role of mode of delivery on el... [J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2014] - PubMed - NCBI. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 2014;29:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]