Abstract

Background

The U.S. federal regulation “Exception from Informed Consent (EFIC) for Emergency Research,” 21 Code of Federal Regulations 50.24, permits emergency research without informed consent under limited conditions. Additional safeguards to protect human subjects include requirements for community consultation and public disclosure prior to starting the research. Because the regulations are vague about these requirements, Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) determine the adequacy of these activities at a local level. Thus there is potential for broad interpretation and practice variation.

Aim

To describe the variation of community consultation and public disclosure activities approved by IRBs, and the effectiveness of this process for a multi-center, EFIC, pediatric status epilepticus clinical research trial. Methods: Community consultation and public disclosure activities were analyzed for each of 15 participating sites. Surveys were conducted with participants enrolled in the status epilepticus trial to assess the effectiveness of public disclosure dissemination prior to study enrollment.

Results

Every IRB, among the 15 participating sites, had a varied interpretation of EFIC regulations for community consultation and public disclosure activities. IRBs required various combinations of focus groups, interviews, surveys, and meetings for community consultation; news releases, mailings, and public service announcements for public disclosure. At least 4,335 patients received information about the study from these efforts. 158 chose to be included in the “Opt Out” list. Of the 304 participants who were enrolled under EFIC, 12 (5%) had heard about the study through community consultation or public disclosure activities. The activities reaching the highest number of participants were surveys and focus groups associated with existing meetings. Public disclosure activities were more efficient and cost-effective if they were part of an in-hospital resource for patients and families.

Conclusion

There is substantial variation in IRBs' interpretations of the federal regulations for community consultation and public disclosure. One of the goals of community consultation and public disclosure efforts for emergency research is to provide community members an opportunity to opt-out of EFIC research; however, rarely do patients or their legally authorized representatives report having learned about a study prior to enrollment.

Keywords/Short phrases: Emergency Research, Exception from informed consent, Community Consultation, Public Disclosure, Pediatrics, Multi-centered randomized double blinded controlled study

Background

Conducting clinical research on life-threatening emergencies in patients unable to consent introduces unique ethical considerations for Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), researchers, and communities.1–7 Even if a patient is conscious or when a legally authorized representative is present to consent, there is often insufficient time to obtain informed consent before an emergent intervention is required.3 Pediatric emergency research adds additional ethical complexity, as children are unable to consent for research without a parent or legal guardian, and must be given an opportunity to provide assent if age-appropriate.

To address these ethical issues in the US, the federal regulation Exception from Informed Consent (EFIC) for Emergency Research, 21 Code of Federal Regulations 50.24, permits emergency research under specific and limited conditions7. Table 1 outlines conditions that must be present for a research study to be approved under EFIC regulations. These conditions offer protections for patients who might qualify for EFIC Emergency Research. To conduct research under EFIC regulations, investigators must demonstrate that informed consent is not practical, that available treatments are unproven or unsatisfactory, and that there is potential direct benefits to the participant. Additional safeguards to protect human subjects include independent safety monitoring and community consultation and public disclosure prior to study initiation. Furthermore, process and ethical considerations for EFIC research when conducted simultaneously across participating sites in a multi-national context are largely unknown despite a growing number of such research endeavors. Canada's EFIC regulations differ somewhat from the US: Canada's Tri-Council's Policy on Final Rule on EFIC research do not require community consultation and public disclosure.8

Table 1. Conditions for research studies under Exception from Informed Consent (EFIC) for emergency research.

| 1 | The research must involve human subjects who cannot consent because of their emerging life-threatening medical condition, for which available treatments are unproven or unsatisfactory |

| 2 | The Intervention must be administered before informed consent is feasible from the patient's legally authorized representative |

| 3 | The sponsor has prior written permission from the FDA |

| 4 | There is an independent data monitoring committee |

| 5 | The relevant IRB has documented that these conditions were met |

| 6 | There is an independent assessment of the risks and benefits of the protocol |

| 7 | Community consultation and public disclosure are performed prior to initiation of the study |

The Code of Federal Regulations for community consultation and public disclosure does not specify the types of activities that should occur. The regulations simply state “1) consultation (including, where appropriate, IRB consultation) with community representatives in which the clinical investigation will be conducted and from which subjects are recruited; 2) public disclosure to the communities where the clinical investigation will be conducted and from which subjects are recruited, prior to initiation of the clinical investigation, and its risks and expected benefits; 3) public disclosure of sufficient information following completion of the clinical investigation to apprise the community and researchers of the study, including the demographic characteristics of the research population, and its results”.9 Guidance documents that elaborate on these regulations were available at the time of study implementation, but instructions were vague and have since been revised.

While all EFIC research studies must conduct community consultation and public disclosure activities, activities can vary extensively among different IRB sites.10 Local IRBs determine what constitutes adequate local community consultation and public disclosure. Furthermore, debate exists whether community consultation and public disclosure activities adequately reach members of the community, which can affect the attitudes towards study participation or the protection of human subjects.1,11–17

A multi-center, prospective, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial was conducted in the US and Canada to compare the efficacy and safety of lorazepam with diazepam in children presenting in the emergency department with generalized convulsive status epilepticus.18 Neurological emergencies in children, such as status epilepticus, are common and are an example of an emergency clinical condition where informed consent from the legally authorized representative may be impractical to obtain because of the patient's altered state of consciousness, the need to emergently treat the patient, and parental anxiety regarding their child's ongoing seizures. This report describes the community consultation and public disclosure procedures approved by IRBs of participating sites, and the effectiveness of this EFIC process in a multi-centered (US and Canadian sites) pediatric clinical research study.

Methods

Setting

Participants were enrolled at 11academic pediatric emergency departments. Initial recruitment was from 12 U.S. sites within the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network19; subsequently three additional sites were added, including two sites from Canada, to augment enrollment.

Institutional Review Board approval

The requirements of EFIC are clearly stated in the regulations and supporting guidance documents, but are not specific or detailed. All sites proposed and received approval from their respective IRBs for community consultation and public disclosure activities prior to site initiation of these activities. The IRB then received a report of the completed activities prior to participant enrollment.

Community consultation and public disclosure tools

The lead site developed a website with community consultation and public disclosure resources, including resources for public relations and media training. Resources included posters, slide presentations for community meetings, brochures, website language for hospital use, letters for referring physicians/community leaders, meeting invitation flyers, newspaper articles and advertisements, hospital on-hold message scripts, and Public Service Announcements. These resources served as templates, and were adapted for community consultation (focus groups, interviews, surveys, and town meetings) or public disclosure (news releases, mailings, and public service announcements) activities as necessary. Materials were modified and translated to other languages according to local IRB requirements. A national website that monitored usage was a public disclosure activity available to all sites.

Community consultation and public disclosure activities were directed at two communities; the general population likely to use emergency departments, and patients and families with known epilepsy. It was important to capture patients from both the general population as well as those with a seizure history as it was anticipated that approximately 35% of patients who qualified for the study would present without a prior seizure.

Eligibility

Children aged 3 months to less than 18 years were eligible for inclusion if they exhibited generalized tonic-clonic status epilepticus from May 2008 to May 2013 at one of the participating emergency departments.

Pre-consent and the “Opt-Out” list

One of the requirements of the EFIC regulations is that investigators must attempt to obtain informed consent when possible. Therefore, as part of the recruitment efforts, families of patients with a history of seizures were approached in pediatric neurology clinics and emergency departments in an effort to obtain informed consent prior to a possible future episode of status epilepticus (pre-consent). This process was ancillary to community consultation and public disclosure efforts, once the study was approved, and was ongoing throughout the study. Those participants who elected to pre-consent were contacted every 90 days for ongoing consent and, when possible, the consent decision was again verified at the time of enrollment and prior to study treatment. Patients and legally authorized representatives who were approached for the pre-consent group prior to enrollment could sign the informed consent document, “opt out”, or learn about the study and decide to neither consent nor “opt out” of the study.

Those who chose to opt out of the study were placed on a national “Opt Out” list that was constantly updated and accessible to all participating sties. In addition, individuals who heard about the study through the public disclosure and community consultation activities could request to be added to the national “Opt Out” list.

Data sources

The data analyzed for this paper were compiled from community consultation and public disclosure summary sheets. Summary sheets included the type of community consultation and public disclosure activities and detailed information regarding the frequency of the activity and, where applicable, the number of potential participants reached. The summary sheets were the primary data source for analysis, and included both quantitative and qualitative information. These summary sheets were reviewed for accuracy by site principal investigators at the time of completion and submitted to the lead principal investigator. From these, a summary table was compiled (see Appendix 1). Additionally, we obtained the number of completed surveys collected centrally at one site. After study completion and prior to analysis, site investigators (JC, JB) again reviewed the summarized table for accuracy. Data were collected and abstracted into a master database (Excel version 2011, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), allowing site comparison.

Additionally, patient-specific data was collected for enrolled participants using a standardized debriefing instrument to determine whether the family had heard about the study prior to enrollment, and if so, the source information (see Appendix 2). The proportion of enrolled participants or their legally authorized representative who were reached by community consultation and/or public disclosure activities was then calculated.

Results

IRB approval and review of community consultation and public disclosure activities varied widely among sites. As a result, they were implemented in different ways at different sites. Variation amongst site IRBs' interpretations of EFIC regulations surrounding community consultation and public disclosure may have led to delays in study initiation in this multi-centered project. The median time from when the sponsor released the protocol to the sites and gave approval to begin consultation and disclosure activities to when sites received final IRB approval was 10 months, with a range of 5 to 26 months. The site with the longest IRB approval time had a change in the IRB Chair during the approval process; excluding this site, the range was 5-17 months. IRB interpretation of regulations may also contribute to variability in the number of activities conducted. On average, sites used 14 different modalities for community consultation and public disclosure, with a range of 9 to 20 modalities.

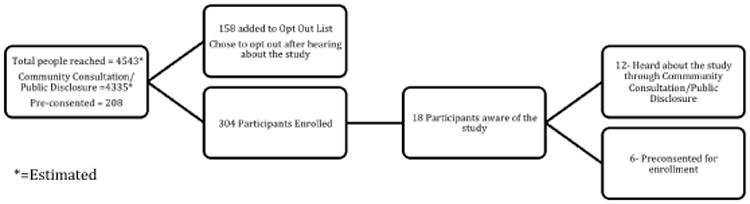

The actual number of patients/families reached by all our EFIC activities is unknown. For example, the number of people who heard a public service announcement was not determined. At least 4,543 patients received study information from our community consultation/public disclosure (4335 patients) and pre-consent (208 patients) efforts (see Figure 1). Of these, 158 chose to be included on the “Opt Out” list. Three hundred and four patients were enrolled in our study, 12 heard about the study through community consultation/public disclosure efforts, and 6 had been pre-consented. Nationally, 208 patients with a history of seizures were pre-consented by their legally authorized representative for enrollment into the study. Of these, 6 (3%) were later enrolled into the study when they experienced a qualifying seizure in study emergency departments. The number of individuals approached for pre-consent was not tracked.

Figure 1. Summary of community consultation and public disclosure efforts.

Table 2 depicts the types of activities used for community consultation and Table 3 shows the activities used for public disclosure. Some sites were able to meet with the IRB to agree on community consultation and public disclosure activities prior to their IRB submission. Other sites, however, had to submit their planned activities with the study proposal before feedback was received on the proposed community consultation and public disclosure plans.

Table 2. Community consultation activities.

| Activity | Number of sites (%) | Number of events (range) | Sites reporting number of participants | Number of participants (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Meetings | ||||

|

| ||||

| General Population Meetings | ||||

| Focus groups | 6 (40%) | 9 (1-2) | 6 | 49 (0-18) |

| Invited presentations | 7 (47%) | 9 (1-3) | 7 | 189 (3-60) |

| Educational meetings | 3 (20%) | 1 4 (1-2) | 3 | 25 (2-10) |

| Open public meetings | 7 (47%) | 19 (1-5) | 7 | 22 (0-50) |

| Seizure Meetings | ||||

| Focus groups | 8 (53%) | 16 (1-3) | 8 | 112 (0-28) |

| Invited presentations | 5 (33%) | 9 (1-3) | 5 | 113 (4-25) |

| Educational meetings | 2 (13%) | 2 (1) | 2 | 10 (3-7) |

| Open public meetings | 4 (27%) | 5 (1-2) | 2 | 111 (0-111) |

|

| ||||

| Surveys/Interviews | ||||

|

| ||||

| Approached participants | 14 (93%) | 24 (1-2) | 14 | 2514 (2-508) |

| Submitted Surveys | 10(66%) | n/a | 10 | 1479 (38-461) |

Table 3. Public disclosure activities.

| III. Public Disclosure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sites participating (% of 15 sites) | Sites with participant information | Total participants (Range Per Site) | Examples | |

|

| ||||

| Mailings | ||||

|

| ||||

| Physicians | 10(67%) | 5 | 464 (1-148)* | Letter to referring physicians/Letter to County Medical Society |

| Seizure Patients and Parents | 5 (33%) | 1 | 694 (132-562)* | Letter to ED and past Children's Health Clinic Patients/Letter to Epilepsy Support Group Foundation Members |

| Schools and Public Officials | 3 (20%) | 1 | 133 (1-133)* | Letter to PTA Leaders within 10 miles of hospital/Letters to Public Officials inviting them to General Community Meeting |

|

| ||||

| Public Media | Not Available | |||

|

| ||||

| TV | 5 (33%) | 5 | TV Interview given by PI/TV PSA | |

| Radio | 5 (33%) | 5 | Radio PSA | |

| Press Releases | 3 (20%) | 3 | Press Release announcing Study/Press Release announcing Community Meetings | |

| Print/Online Media | 12 (80%) | 12 | Newspaper Article/National Study website/Hospital website/Site Study Website | |

| Telephone | 1 (7%) | 1 | 24-hour hotline | |

|

| ||||

| In-Hospital | Not Available | |||

|

| ||||

| Flyers | 5 (33%) | 5 | ED/Neurology Clinic Waiting Rooms | |

| Brochures | 7 (47%) | 7 | ED/Neurology Waiting and Exam Rooms | |

| Online | 6 (40%) | 6 | Ad placed on Hospital website/Announcement via Hospital's Facebook and Twitter pages | |

| Telephone | 2 (13%) | 2 | Recording on Hospital on-hold message/Toll-free local number for community members to leave messages | |

| Posters | 9 (60%) | 9 | ED waiting rooms, neurology clinics, individual ED pt. rooms, general clinic research waiting rooms, main hospital entrances, information boards outside hospital elevators | |

| Interpersonal Newsletter | 3 (20%) | 3 | Study announcement on hospital in-house newsletter for Medical Staff/Article in Hospital E-Newsletter | |

= unreliable average due to low site reporting

Community consultation activities

In general, sites conducted community consultation efforts to reach two separate groups: the general community, and the community of people who have epilepsy or have a close relationship with a person with epilepsy or special needs. Table 2 outlines the type of community consultation activities used to reach the general and seizure populations. Activity subtypes were large group meetings and individual, interactive surveys or interviews.

For the general population, the most common community consultation meetings included open public meetings such as health fairs (47% of sites), invited presentations (47%), and focus groups (40% of sites). For the seizure population, the most common community consultation meetings were focus groups (53%), invited presentations (33%), and open public meetings (27%). Examples of invited presentations included seizure support groups, church groups, community health centers, conferences, and residential council meetings.

Focus groups not associated with another meeting were not well attended. A total of 8 sites used focus groups, offering 24 focus group meetings. Of these, 6 meetings (25%) had no attendees. Similarly, sites that held stand-alone open public meetings were more likely to have few or no participants than those who offered study information at a pre-established community event (such as a health fair). The invited presentations had the highest number of attendees per meeting. In addition, meetings associated with seizures were better attended as compared to other general community meetings.

Surveys were used as another means of community consultation. Participants were provided with study information and then asked to provide feedback. Surveys were conducted at 14 of the 15 sites. One site did not conduct surveys because their IRB preferred focus groups as a methodology for community consultation. Surveys were conducted at neurology clinics, community clinics, meetings, community events, and in various emergency departments. One site conducted a general survey with the provision of information, to the population surrounding their hospital using random digit dialing with a phone number associated within a zip code located within 50 miles of the hospital. Overall, at least 2,684 surveys were offered at 14 sites and 1,479 surveys from 10 sites were submitted to a central data repository.

Public disclosure activities

Public disclosure activities are depicted in Table 3 and included mailings, public media, and in-hospital activities. Mailings were categorized as mailings to physicians (67% of sites), seizure patients and parents (33%), and schools and public officials (20%). Public media announcements included TV interviews (33% of sites), radio interviews or announcements (33%), local press releases (20%), print or online media (80%), and telephone (7%). The lead site created a national press release that was picked up locally by many sites. After the national press release, several sites conducted TV, radio or newspaper interviews. Public service announcements varied from site to site depending on the demographics of the community and recommendations from the IRB. One site offered all their public disclosure activities in both English and Spanish. The requirements for frequency of radio advertisements varied among sites. Some site IRBs recommended scheduling them just once over the course of study while others were required by their IRB to schedule radio announcements as often as twice a day for two weeks or 60 seconds every other month throughout the length of the study. Newspapers articles following an interview or paid advertisements were also used for public disclosure at many sites. Online information was posted on hospital websites (40% of sites) as well as the lead study website. Hospital Twitter© and Facebook© accounts were also used at one site. The centralized website was visited by 1,273 people during the study period. The most common in-hospital activities for public disclosure were posters (60% of sites), brochures (47%), on-line information (40%), flyers (33%), interpersonal newsletter (20%), and hospital telephone recording (13%).

Post enrollment debriefing surveys

Of the 310 participants enrolled, six were pre-consented, and 304 were enrolled under EFIC. Ninety-eight participants (32%) did not have a history of seizure prior to enrollment. Of the 304 participants who were not pre-consented, 297 had a debriefing form completed. Twelve (5%) heard about the study through community consultation or public disclosure activities. Of these, 10 people indicated they had received this information as part of an in-hospital resource such as a poster, or interaction with medical or study staff. Two participants reported receiving information from two separate in-hospital sources. The remaining two people indicated they had heard about the study from a letter in the mail (1), or at their primary care physician's office (1).

Site budgets for community consultation and public disclosure

The majority of costs for community consultation and public disclosure were incurred during the first year start-up phase. The lead site's total budget was $18,135. This accounted for the costs associated with development of the centralized website, resources, and media training program requirements. However, sites had varying requirements for continued public disclosure throughout the study period that may have increased their budget over other sites. Additionally, all sites were required to disclose study results after the study was complete. The remaining 14 sites (excluding the lead site), had a wide variation of community consultation and public disclosure costs ($1,523-$10,374) with a median of $6,989 and an interquartile range of $3,942 and $7,250.

Discussion

This report analyses the first US and international pediatric study conducted under 21 Code of Federal Regulations 50.24 (EFIC). Regulation guidance of EFIC was included in the Federal Register with publication of the final rule in 1996, which was supplemented by an Federal Drug Administration information sheet in 1998 and a guidance document in 2002. Our community consultation and public disclosure activities were conducted after the release of the 2006 new draft guidance and prior to the release of the finalized EFIC guidance document in 2011 and revised document in 2013.20 Community consultation and public disclosure activities allow community members to learn about potential studies, discuss the “ethics” and “fairness” of the study, and if necessary, notify investigators regarding problematic aspects of the study related to their specific community. If the general public considers the risks too high or if the community was uncomfortable with the proposed study, the investigators may need to modify the protocol. These activities also provide opportunities for some individuals to prospectively “enroll” or “opt out” of a study.

The analysis of the EFIC activities highlights important features of EFIC and the most effective methods for reaching large numbers of patients/families in the community. This has important implications for pediatric emergency research. Most importantly, there is wide variability in IRBs' interpretations of the federal rules and requirements for community consultation and public disclosure. For example, one IRB viewed surveys as a surrogate community consent process and would not approve the study unless responses met a pre-specified threshold of approval of the study. This is not consistent with the intention of the EFIC regulations; community “consent” cannot substitute for individual participant or legally authorized representative consent. Another example of variability occurred when sampling communities. Although most sites favored face-to-face meetings or interviews with communities, one site required random digit dialing of the region around the hospital. This site's definition of community is fundamentally different than the other sites' definition of community. These examples of variability demonstrate that the broadly described verbiage in the regulations, perhaps meant to allow flexibility in interpretation from trial to trial, may have unintentionally contributed to variability from IRB to IRB within a single trial.

Other studies have also noted that the federal requirements for community consultation and public disclosure are undefined and left up to the interpretation of local IRBs and researchers.1,2,5,10 This variability allows for local IRBs to tailor federal recommendations to their community and patient population.14 Previous EFIC studies of adult subjects outline suggestions for community consultation and public disclosure.12,13,21–35 It is interesting to note that adult survivors who were enrolled into EFIC trials, the medical community, and members of the general community are generally willing to take part in emergency medical research, even if they were unable to give consent.13,21–25,35 People were more concerned, however, with the risks and benefits of the research rather than the absence of informed consent.13,22,23,25 Some recommend that the amount of required community consultation or public disclosure activities should be based on the incremental risks of a study.10,34,35 Although most EFIC studies have the potential to enroll anyone from the entire community, some studies are more likely to enroll patients with a particular risk factor and thus may be targeted.

The community consultation and public disclosure activities in this study did not reach a large proportion of enrolled participants or their families; of the 297 enrolled subjects for which debriefing information was collected, 12 (5%) had heard about the study prior to enrollment. While community consultation and public disclosure did demonstrate some effectiveness, it was albeit very low relative to the 95% who were not aware of the study. However, community consultation and public disclosure efforts did allow 158 potential patients to be placed on the “Opt Out” list for the study, an important safeguard that is recommended, but not required, under the EFIC federal regulations.

Some community consultation and public disclosure activities were more effective than others in reaching large numbers of community members. The activities that reached the largest number of participants were surveys and focus groups associated with existing meetings. Community consultation activities not associated with other meetings were poorly attended. Interestingly, of the 6 meetings with no attendees, 2 of the meetings were attempted at the site where the IRB preferred focus groups to surveys as a means of community consultation. Public disclosure activities were more efficient and cost-effective if they were part of an in-hospital resource to patients and families or through TV, radio or newspaper interviews. Researchers, however, need to be prepared for interviews, as information disclosed to the public can be misleading. One study identified 20% local media reporting errors, which could influence the public's opinion about EFIC research.32 Paid media advertisements were costly and shown to have little effect in reaching study participants as none of the enrolled participants cited TV as a source of study information. Broadcast exposure also may be relegated to low audience hours or channels, thus limiting the public disclosure impact. This was not analyzed.

Attempting to identify potential seizure patients prior to an episode of status epilepticus is not an efficient method for enrolling patients. Of 208 patients pre-consented for this study, only 6 (3%) were eventually enrolled., However, this process was a successful form of ongoing public disclosure. Furthermore, pre-consent could not have identified the 32% of patients who presented with a first seizure as their qualifying episode of status epilepticus.

There is limited literature examining attitudes and effectiveness of community consultation and public disclosure in pediatric EFIC emergency research because little EFIC research has been conducted in children.1,2,7,10,27,28,36–38 However, parent interviews in a pediatric emergency departments reveal a willingness to participate in EFIC research. 36 Recommendations on community consultation and public disclosure activities are to target populations that could be enrolled, and, if possible, directly contact parents so they have an opportunity to pre-consent and opt-out. 8,25,38

This study has several strengths. First, it describes the community consultation and public disclosure employed for the first pediatric emergency department-based EFIC study with qualitative and quantitative data. As such, this is the first study reporting the community consultation and public disclosure activities for an EFIC study of a specific pediatric medical condition. Additionally, because this study was multi-centered and international, the sites conducted a wide range of activities to meet specific IRB and community requirements demonstrating the wide interpretation by IRBs on what constitutes adequate community consultation and public disclosure. This study provides specific examples of activities effective at reaching community members and study patients prior to enrollment. Our results may be helpful for future trials requiring community consultation and public disclosure. Furthermore, results from our study may help federal agencies and IRBs refine their recommendations for EFIC studies for children and adults.

This study does have limitations. Although most sites tracked the number of people contacted with each activity, two sites did not track their meetings or their mailings. Furthermore, for some public disclosure activities (e.g. TV and radio announcements), it is impossible to calculate the true number of people informed. We would expect that the total number reached by the media to be far larger than we reported. This study did determine how enrolled participants heard about the study prior to enrollment but it did not determine how the individuals who “Opted Out” heard about the study. In addition, we only have data available for the pre-consent cohort that had provided formal consent. In retrospect, we should have tracked how many were approached and decided to “Opt-Out” or neither give consent or “Opt-Out”. While the pre-consent effort was considered a recruitment effort, rather than public disclosure, the pre-consent process provided opportunity for populations to become informed and is included here as an adjunct to public disclosure. Further, we did not track how many eligible patients were excluded because they were found on the opt-out list. This information would have helped us to further evaluate the community consultation and public disclosure efforts.

Finally, although sites' total costs of community consultation and public disclosure activities are known, specific activities costs are unknown. This information would have been helpful in determining cost-effectiveness for these activities.

Pediatric EFIC research is important to improve clinical outcomes in emergent situations and provide the best medical care possible. 16 Federal community consultation and public disclosure regulations for EFIC research are vague and left up to local IRB interpretation. 3 This pediatric seizure EFIC study found community consultation and public disclosure activities most successful at reaching our community were in-hospital resources/advertisements, interviews, surveys, and presentations/focus groups connected to established meetings. Future research should assess the best way to conduct community consultation and public disclosure in the most effective and cost-efficient manner.15,39

Acknowledgments

Funding and support: This study was funded by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network is supported by cooperative agreements from the Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) program of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB), Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. The Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act Data Coordinating Center for this study was the EMMES Corp and was funded by the NICHD under a separate contract. Further details on the grants that supported this study are listed in Appendix 3.

Role of sponsors: The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) helped design and conduct the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Further details on the role of sponsors is provided in Appendix 3

Group information: Membership of the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network is provided in Appendix 3

Appendix 1- Blank summary form

| SITE NAME: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Type:

|

Frequency:

|

Documents Used | Comments | Additional details | |

| Meetings | ||||

| Focus Groups | ||||

| Invited presentation and discussion at special meetings (such as community advisory board meetings) | ||||

| Ad hoc meetings with community leaders | ||||

| Open Public Forum etc (e.g. health fairs, radio talk show) | ||||

|

When (Time period) | Documents Used | ||

| Survey Interviews | ||||

|

When (Time period) | Document(s) mailed | ||

| Mailings | ||||

| Type: | Name: | Frequency: | Documents Distributed | |

| Public Media | ||||

| Type: | Details: | Frequency: | Documents used | |

| In-Hospital Resources | ||||

| Type | Details | Frequency | Documents used | |

| Other | ||||

Appendix 2- Blank debriefing form

| Patient Randomization #: _____________ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date enrolled: | Date debriefing form completed: | |||

| Question | Answer | |||

| 1. Did a member of the treatment team have an opportunity to discuss the study with a member of the family prior to the full consent process? | □No □Yes (If yes, please enter the duration) Minutes: _______ Seconds: _______ |

|||

| 2. How long did it take you to approach the family after the child had automatically been enrolled? | Hour(s): _______ Minutes: _______ | |||

| 3. Who approached the family to conduct the informed consent conversation? | □ Site- PI □ Sub-I □ Research coordinator □ Other research personnel: Role: ______________ □ Other clinical personnel: Role: ______________ |

|||

| 4. How long did the entire informed consent process take? (Please estimate total time and give best estimate of breakdown into categories in minutes)? | Total Time: Hour(s): _____ Minutes: _____ Breakdown minutes for each category below:

|

|||

| 5. Did the treating clinical staff introduce you to the family before the informed consent process? | □ No □ Yes If yes, who made the introduction? □ MD □ Social worker □ RN □ Other (Specify): ____________________ □ Chaplain |

|||

| 6. Had the family heard of the study prior to the ED visit? | □ No □ Yes If yes, how did they hear about it? □ Television spot □ Radio spot □ Newspaper □ Letter in the mail □ Their personal physician □ Poster around hospital □ Hospital newsletter □ Community meeting □ Other (describe): ______________________________ |

|||

| 7. What was the behavioral/emotional state of the parent over time? (Check all that apply) | -Interested/Engaged -Calm/Receptive -Ambivalent -Inattentive -Distracted -Anxious -Tearful -Distraught -Verbally aggressive -Physically aggressive -Other (describe): |

Initial Reaction: | During Consent: | After Consent: |

| □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ ___________ |

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ ___________ |

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ ___________ |

||

| 8. Please check if any of the following were mentioned by parents/guardians for additional explanation, clarification, or direct questioning during the informed consent process? | -Doing the study without prospective informed consent □ -Child' eligibility to participate □ -Use of off-label medication □ -Request for unblinding □ -Potential adverse events associated with study medication or being in a clinical trial □ -Other (please describe): _______________________ |

|||

| 9. What was the result of the informed consent discussion? | -Parent gave consent for the child to participate in all study procedures □ -Parent denied consent for participation □ -Parent gave consent for use of all data but denied consent for second IV placement □ |

|||

| 10. Please describe things that went well and/or did not go well during the informed consent discussion? | Describe: | |||

Appendix 3: Acknowledgments

Funding and support

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grant number is HHSN275201100017C. The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network is supported by cooperative agreements U03MC00001, U03MC00003, U03MC00006, U03MC00007, and U03MC00008 from the Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) program of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB), Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services.

Role of the sponsors

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The NICHD commissioned an expert panel of ethicists, regulatory experts, and attorneys to advise the investigators on the proper conduct of the Exception from Informed Consent; convened the Data Safety Monitoring Board; contracted with the Data Coordinating Center to provide data management and data analysis and to aid with interpretation of study results; reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission; and approved the final manuscript prior to submission.

Group Information

The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network includes the following investigators: Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA)

Data Coordinating Center (DCC): The EMMES Corp: D. King, C. Kim, K. Martz, and J. Zhao. BPCA Data Monitoring Committee (DMC): P. Walson (chair), K. Weise, A. Das, D. Venzon, B. Wiedermann, G. Koren, C. Vocke, A. Thompson, N. Harris, M. Riddle, L. Brown, P. Swerdlow, and A. Zajicek. Participating centers and site investigators: Children's Hospital, Boston: L. Nigrovic; Children's Hospital of Buffalo: K. Lillis; Children's Hospital of Michigan: P. Mahajan; Children's Hospital of New York– Presbyterian: M. Sonnett; Children's Hospital of Philadelphia: K. Shaw; Children's Memorial Hospital: E. Powell; Children's National Medical Center: K. Brown; Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center: R. Ruddy; DeVos Children's Hospital: J. Hoyle; Hurley Medical Center: D. Borgialli; Jacobi Medical Center: Y. Atherly-John; Medical College of Wisconsin/Children's Hospital of Wisconsin: M. Gorelick; University of California Davis Medical Center: E. Andrada; University of Michigan: R. Stanley; University of Rochester: G. Conners; University of Utah/Primary Children's Medical Center: D. Nelson; Washington University/St. Louis Children's Hospital: D. Jaffe; University of Maryland: R. Lichenstein. Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network Steering Committee: P. Dayan (chair); E. Alpern, L. Bajaj, K. Brown, D. Borgialli, J. Chamberlain, J. M. Dean, M. Gorelick, D. Jaffe, N. Kuppermann, M. Kwok, R. Lichenstein, K. Lillis, P. Mahajan, D. Monroe, D. Nelson, L. Nigrovic, E. Powell, A. Rogers, R. Ruddy, R. Stanley, M. Tunik. MCHB/EMSC liaisons: D. Kavanaugh and H. Park. Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network Data Coordinating Center (DCC): J. M. Dean, H. Gramse, R. Holubkov, A. Donaldson, C. Olson, S. Zuspan, and R. Enriquez. Feasibility and Budget Subcommittee (FABS): K. Brown, S. Goldfarb (co-chairs); E. Crain, E. Kim, S. Krug, D. Monroe, D. Nelson, M.

Berlyant, and S. Zuspan. Grants and Publications Subcommittee (GAPS): M. Gorelick (chair); L. Alpern, J. Anders, D. Borgialli, L. Cimpello, A. Donaldson, G. Foltin, F. Moler, and K. Shreve. Protocol Review and Development Subcommittee (PRADS): L. Nigrovic (chair); J. Chamberlain, P. Dayan, JM. Dean, R. Holubkov, D. Jaffe, E. Powell, K. Shaw, R. Stanley, and M. Tunik. Quality Assurance Subcommittee (QAS): K. Lillis (chair); E. Alessandrini, S. Blumberg, R. Enriquez, R. Lichenstein, P. Mahajan, R. McDuffie, R. Ruddy, B. Thomas, and J. Wade. Safety and Regulatory Affairs Subcommittee (SRAS): W. Schalick, J. Hoyle, (co-chairs); S. Atabaki, K. Call, H. Gramse, M. Kwok, A. Rogers, D. Schnadower, and N. Kuppermann.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: This study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), Grant # HHSN275201100017C.

The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network is supported by cooperative agreements U03MC00001, U03MC00003, U03MC00006, U03MC00007, and U03MC00008 from the Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) program of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflict of Interest: None

Bibliography

- 1.Ernst AA, Weiss SJ, Nick TG, et al. Minimal-risk waiver of informed consent and exception from informed consent (final Rule) studies at institutional review boards nationwide. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1134–1137. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison CA, Horwitz IB, Carrick MM. Ethical and legal issues in emergency research: barriers to conducting prospective randomized trials in an emergency setting. J Surg Res. 2009;157:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt TA, Salo D, Hughes JA, et al. Confronting the ethical challenges to informed consent in emergency medicine research. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1082–1089. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt TA, Lewis RJ, Richardson LD. Current status of research on the federal guidelines for performing research using an exception from informed consent. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1022–1026. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaslef S, Cairns C, Falletta J. Ethical and regulatory challenges associated with the exception from informed consent requirements for emergency research: from experimental design to institutional review board approval. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1019–1023. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.10.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris MC. An ethical analysis of exception from informed consent regulations. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2005;12:1113–1119. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.03.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watters D, Sayre MR, Silbergleit R. Research conditions that qualify for emergency exception from informed consent. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1040–1044. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson J. Ethical challenges of informed consent in prehospital research. CJEM Can J Emerg Med care = JCMU J Can soins medicaux d'urgence. 2003;5:108–114. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500008253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Food Drug Administration. [Accessed 8 May 2014];Exception from informed consent for studies conducted in emergency settings: regulatory language and excerpts from preamble - information sheet - guidance for institutional review boards and clinical investigators. 2010 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm126482.htm.

- 10.Biros M. Struggling with the rule: the exception from informed consent in resuscitation research. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:344–5. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delorio NM, McClure KB. Does the emergency exception from informed consent process protect research subjects? Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1056–1059. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longfield JN, Morris MJ, Moran KA, et al. Community meetings for emergency research community consultation. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:731–736. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.OB013E318161FB82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickert N, Kass N. Patients' perceptions of research in emergency settings: a study of survivors of sudden cardiac death. [Accessed 8 May 2014];Soc Sci Med. 2009 68:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.001. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953608005224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salzman JG, Frascone RJ, Godding BK, et al. Implementing emergency research requiring exception from informed consent, community consultation, and public disclosure. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:448–455. 455.e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson LD, Wilets I, Ragin DF, et al. Research without consent: community perspectives from the community VOICES study. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1082–1090. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baren JM, Fish SS. Resuscitation research involving vulnerable populations: are additional protections needed for emergency exception from informed consent? Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1071–1077. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson LD, Quest TE, Birnbaum S. Communicating with communities about emergency research. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1064–1070. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chamberlain JM, Okada P, Holsti M, et al. Lorazepam vs diazepam for pediatric status epilepticus: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1652–1660. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dayan P, Chamberlain J, Dean JM, et al. The pediatric emergency care applied research network: progress and update. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2006;7:128–135. [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Food Drug Administration. [accessed 8 May 2014];Guidance for institutional review boards, clinical investigators, and sponsors: Exception from informed consent requirements for emergency research. 2011 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/regulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm249673.pdf.

- 21.Sims CA, Isserman JA, Holena D, et al. Exception from informed consent for emergency research: consulting the trauma community. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:157–165. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318278908a. discussion 165-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein JN, Espinola JA, Fisher J, et al. Public opinion of a stroke clinical trial using exception from informed consent. Int J Emerg Med. 2010;3:385–389. doi: 10.1007/s12245-010-0244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein J, Delaney K, Pelletier A, et al. A brief educational intervention may increase public acceptance of emergency research without consent. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:419–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasner SE, Baren JM, Le Roux PD, et al. Community views on neurologic emergency treatment trials. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:346–354.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silbergleit R. Response to Food and Drug Administration draft guidance statement on research into the treatment of life-threatening emergency conditions using exception from informed consent: testimony of the neurological emergencies treatment trials. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:e63–e68. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McClure KB, Delorio NM, Gunnels MD, et al. Attitudes of emergency department patients and visitors regarding emergency exception from informed consent in resuscitation research, community consultation, and public notification. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:352–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacoby LH, Young B, Watt J. Public disclosure in research with exception from informed consent: the use of survey methods to assess its effectiveness. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2008;3:79–87. doi: 10.1525/jer.2008.3.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynch CA, Houry DE, Dai D, et al. Evidence-based community consultation for traumatic brain injury. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:972–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosesso VN, Brown LH, Greene HL, et al. Conducting research using the emergency exception from informed consent: the public access defibrillation (PAD) trial experience. Resuscitation. 2004;61:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosesso VN, Cone DC. Using the exception from informed consent regulations in research. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1031–1039. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson M, Schmidt TA, DeIorio NM, et al. Community consultation methods in a study using exception to informed consent. Prehospital Emerg Care. 2008;12:417–425. doi: 10.1080/10903120802290885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson MJ, DeIorio NM, Schmidt T, et al. Local media influence on opting out from an exception from informed consent trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santora T, Cowell V, Trooskin S. Working through the public disclosure process mandated by use of 21 CFR 50.24 (exception to informed consent): guidelines for success. J Trauma. 1998;45:907–913. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sloan EP, Koenigsberg M, Houghton J, et al. The informed consent process and the use of the exception to informed consent in the clinical trial of diaspirin cross-linked hemoglobin (DCLHb) in severe traumatic hemorrhagic shock. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:1203–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sloan E, Nagy K, Barrett J. A proposed consent process in studies that use an exception to informed consent. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:1283–1291. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baren JM, Anicetti JP, Ledesma S, et al. An approach to community consultation prior to initiating an emergency research study incorporating a waiver of informed consent. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:1210–1215. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baren JM, Biros MH. The Research on Community Consultation: An Annotated Bibliography. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:346–352. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris MC, Fischbach RL, Nelson RM, et al. A paradigm for inpatient resuscitation research with an exception from informed consent. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2567–2575. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239115.76603.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramsey C, Quearry B, Ripley E. Community consultation and public disclosure: preliminary results from a new model. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:733–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]