Abstract

Background

Chronic sinonasal disease is common in asthma and associated with poor asthma control; however there are no long term trials addressing whether chronic treatment of sinonasal disease improves asthma control.

Objective

To determine if treatment of chronic sinonasal disease with nasal corticosteroids improves asthma control as measured by the Childhood Asthma Control Test (cACT) and Asthma Control Test (ACT) in children and adults respectively.

Methods

A 24 week multi-center randomized placebo controlled double-blinded trial of placebo versus nasal mometasone in adults and children with inadequately controlled asthma. Treatments were randomly assigned with concealment of allocation.

Results

237 adults and 151 children were randomized to nasal mometasone versus placebo, 319 participants completed the study. There was no difference in the cACT (difference in change with mometasone – change with placebo [ΔM - ΔP]: -0.38, CI: -2.19 to 1.44, p = 0.68 ages 6 to 11) or the ACT (ΔM - ΔP: 0.51, CI: -0.46 to 1.48, p = 0.30, ages 12 and older) in those assigned to mometasone versus placebo. In children and adolescents, ages 6 to 17, there was no difference in asthma or sinus symptoms, but a decrease in episodes of poorly controlled asthma defined by a drop in peak flow. In adults there was a small difference in asthma symptoms measured by the Asthma Symptom Utility Index (ΔM - ΔP: 0.06, CI: 0.01 to 0.11, p <0.01) and in nasal symptoms (sinus symptom score ΔM - ΔP: -3.82, CI: -7.19 to- 0.45, p =0.03), but no difference in asthma quality of life, lung function or episodes of poorly controlled asthma in adults assigned to mometasone versus placebo.

Conclusions

Treatment of chronic sinonasal disease with nasal corticosteroids for 24 weeks does not improve asthma control. Treatment of sinonasal disease in asthma should be determined by the need to treat sinonasal disease rather than to improve asthma control.

Keywords: Asthma, rhinitis, sinusitis, sinonasal, asthma control, lung function, asthma exacerbation

Introduction

Poor asthma control is a significant cause of morbidity. One important factor thought to affect asthma control is disease of the upper airway, rhinitis and sinusitis. 1-5 Therefore, chronic sinonasal disease is often treated in patients with asthma in an effort to improve asthma control. However, while acute and severe sinonasal disease clearly warrant treatment directed towards disease in the upper airway, it is not clear if treating chronic sinonasal disease improves asthma control.

Rhinitis, sinusitis and asthma are closely linked. At least 70% of asthmatics have rhinitis,6,7 and 30 – 40 % report sinusitis.6 A number of mechanisms link sinonasal disease and asthma, which may represent a common immune disorder affecting the whole respiratory system. Allergen challenge in one region produces inflammation in the other,8,9 post-nasal drip of inflammatory mediators may occur,10 and a nasobronchial reflex may produce bronchoconstriction.11 Chronic sinonasal disease is very common in asthma, and may be part of a common disease process.

Despite sinonasal disease and asthma being closely related disease processes, it is not clear whether treatment of sinonasal disease affects the course of asthma. Treatment of severe and acute sinonasal disease is clearly warranted and may improve asthma control,12,13 but most studies have been observational as such sinonasal disease requires treatment regardless of the effect on asthma. 12 Some small studies suggest that treatment of acute rhinitis improves airway reactivity14,15 whereas others do not,16,17 and some observational studies report that long term treatment for sinonasal disease improves asthma outcomes.18 However, there are no controlled studies suggesting that long-term treatment of chronic sinonasal disease improves asthma control, although this is often done in clinical practice.19

One barrier to understanding the interaction between sinonasal disease and asthma is the lack of simple tests to diagnose rhinitis and sinusitis in asthma. We previously developed a clinical tool to identify chronic rhinitis and sinusitis in patients with inadequately controlled asthma. This questionnaire, which specifically asks about symptoms experienced over the last 3 months, identifies patients with chronic rhinitis and sinusitis with a sensitivity of 0.90 and specificity of 0.94.20 This questionnaire accurately diagnoses chronic sinonasal disease in asthma, is inexpensive and simple to use, and so facilitates the study of the relationship between chronic sinonasal disease and asthma.

Chronic sinonasal disease is common in asthma and may be associated with severe disease, but the effect of long-term treatment of sinonasal disease on asthma control is not known. The purpose of this study was to determine the efficacy of treating chronic sinonasal disease in children and adults with inadequately controlled asthma, as is common medical practice. There is supportive but inconclusive evidence that such treatment reduces asthma morbidity, and so this clinical trial addresses an important, practical issue that has extensive implications for public health and health care costs.

The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT01118312 under the acronym Study of Asthma and Nasal steroids (STAN).

Methods

Study Design

This was a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-masked, parallel (allocation ratio 1:1) design trial conducted at 19 clinical centers from June 2010 through February 2013. Randomization was stratified by center and age, 6 to 17 years or 18 or older, using permuted blocks of varying sizes. Participants aged 12 years and older received 2 sprays of mometasone or placebo per nostril daily (50 mcg mometasone per spray, versus vehicle control supplied by Merck), those age 6 to 11 years received 1 spray per nostril daily. After a two-week run-in, participants were randomized and followed for 24 weeks while on treatment. Allocation concealment was enforced as follows: clinical center personnel keyed eligibility data into a centralized, web-based randomization system to receive a study kit number that corresponded to the assigned treatment. Unique drug assignment numbers were used to distribute and track study drug. Personnel at the data coordinating center involved in randomization and drug distribution to the centers had access to the treatment information; no personnel at the clinical sites had access to the treatment codes. Analysts looked at treatment identity after data collection was completed and were aware of treatment assignment when performing the analyses of the completed dataset.

Participants

Participants were aged 6 years and older with a history of physician diagnosed asthma and either a positive methacholine challenge (20% fall in FEV1 at less than 16mg/mL of methacholine) in the previous 2 years, or documentation of at least 12% and 200 cc increase in FEV1 with bronchodilator in the previous 2 years. Subjects were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: poor asthma control defined as a score of 19 or less on the Childhood Asthma Control Test (c-ACT) (6-11 years)21 or Asthma Control Test (ACT) (12 years or older)22 (the ACT and cACT of ≤ 19 identifies “not well controlled asthma”, defined as an asthma specialist's rating of not controlled at all/poorly controlled/somewhat controlled) 21,23 and chronic symptoms of rhinitis and sinusitis as measured by a mean score of 1 or greater on the Sino-Nasal Questionnaire. 20 Participants were excluded if they had co-morbidities predisposing to complicated rhinosinusitis; chronic illnesses which in the judgment of the physician would interfere with study participation; history of upper airway symptoms for less than 8 weeks at the time of randomization; fever >38.3°C within the prior 10 days; sinus surgery within the prior 6 months; use of systemic or nasal corticosteroids within the prior 4 weeks or anti-leukotriene medication within the prior 2 weeks; FEV1 less than 50% predicted pre-bronchodilator; greater than 10 pack year smoking history or active smoking within the last 6 months; cataracts, history of glaucoma or other conditions resulting in increased intraocular pressure. Other exclusion criteria were non-adherence (<80% completion of daily diaries during run-in); inability to take study medications, perform baseline measurements or be contacted by telephone; or pregnancy.

Participants underwent allergen skin testing at baseline: Percutaneous allergen scratch skin testing was performed using a Multi-Test II device( Lincoln Diagnostics, Decatur, IL) and 16 allergens ( Mite mix, Cockroach mix, Mouse, Rat, Penicillium, Alternaria, Aspergillus, Cladosporium, Cat, and Dog, 4 local center-specific allergens, and positive and negative controls) (Greer, Lenoir, NC). A positive test was defined as a wheal 3 mm greater than the negative control.

Participants were asked to refrain from taking non-study medications (other than topical decongestants or saline) for their nasal symptoms. They were trained to exhale all orally inhaled corticosteroids through the mouth, to avoid any potential benefit of orally inhaled corticosteroids on the nasal mucosa. Participants continued on their usual asthma medications during the trial. After randomization, participants kept daily diaries to record morning peak expiratory flow (PEF), medication use and asthma symptoms and returned for assessments at 4, 12 and 24 weeks. Procedures performed at each visit included: an interval medical history interview, asthma and sinus symptoms questionnaires, and spirometry ( Koko Spirometer, Ferris Respiratory, Louisville, CO) according to ATS standards.24 At baseline and the 24 week follow-up visits, exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) was measured using the Insight eNO System (Apieron, Menlo Park, California) and methacholine challenge testing was performed. Allergen skin testing and the sinonasal questionnaire were administered at baseline.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was the change in childhood asthma control test (c-ACT for children under 12 years of age) 21or asthma control test (ACT for those ages 12 and older22) at 24 weeks from baseline. Secondary outcomes included changes in methacholine reactivity, asthma symptoms (Asthma Symptom Utility Index [ASUI]),25 asthma-related quality of life questionnaires (Childhood Health Survey for Asthma [CHSA]26 or Marks Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire [Marks AQLQ]27), sinusitis and rhinitis symptoms including a sinus symptom questionnaire28 and sinusitis related quality of life questionnaires ( SinoNasal survey-5 [SN5]29 for 6-17 years, and SinoNasal Outcome Test 22 [SNOT22]30 for 18 years and older), spirometry and exhaled nitric oxide. Secondary outcomes also included the rate of acute episodes of poor asthma control defined as a decrease of greater than 30% in morning peak flow rate from personal best (assessed during run-in) for 2 consecutive days, addition of an oral corticosteroid to treat asthma symptoms, unscheduled contact with a health care provider for asthma symptoms or increased use of short acting β-agonists (≥ 4 additional puffs of rescue medication or ≥2 additional nebulizer treatments in 1 day). Participants were also questioned about potential adverse effects of treatment at each visit and rhinitis/sinusitis exacerbations.

Study Oversight

The Steering Committee of the ALA-ACRC designed, approved, and oversaw the study implementation. Active drug and placebo were supplied by Merck, who had no role in designing, conducting, or approving the study or analyzing the results. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each center. The participant or their legal guardians signed informed consent statements. Participants under 18 years of age signed assents according to local regulatory policies. The ALA-ACRC is not bound by any confidentiality agreement in respect to the study results.

Statistical Approach

All analyses were stratified by age (pediatric [6-17] and adult [ages 18 and older]). The pediatric age category was further divided into younger children (ages 6-11) and adolescents (ages 12-17). The ACT score analysis was stratified by age groups of 6 to 11 years and 12 years and older, the age ranges validated for the pediatric cACT and adult ACT instruments, respectively. For all other outcomes, the two age groups were defined as 6 to 17 years and age 18 years and older. The randomization was stratified according to the age 18 cut-point.

The planned sample size of 190 adult participants (95 on active and 95 on placebo therapy) had 90% power to detect a difference of 2.8 in the change in ACT score from baseline to 24 weeks for the mometasone versus the placebo group with a type 1 error rate of 2.5% and a standard deviation of 5 (this standard deviation was based on prior data from studies by this research network, and previous publications).31,32 Assuming equal recruitment, the same calculation was applied for pediatric patients for a total sample size of 380 and a total type 1 error rate of 5%. However, of the 151 participants less than 18 years of age enrolled in the study, only 86 were between the ages of 6 and 11, the age range for the cACT questionnaire, so the actual detectable difference was larger for that subgroup (approximately 4.1). The sample size calculations include an increase of 11% to account for missing data and lost-to-follow-up.

The analysis of the primary outcome, change in ACT score, incorporated the repeated measures through the use of linear mixed effects models, which are robust to data that is missing at random (MAR). Treatment, visit, and the interaction between treatment and visit were included as fixed effects and an unstructured variance-covariance matrix was used. Contrasts were used to produce the estimates for the change over 24 weeks.

Analyses of continuous secondary outcomes followed the same analytic strategy used for the primary outcome. PC20 (measured at baseline and 24 weeks) was analyzed on the log scale and results were translated into % change. Rates of exacerbations were evaluated using Negative Binomial models. All randomized individuals were included in the analysis according to their assigned treatment group. Robust variance estimates were used for all analytic models. The primary analyses were performed independently by two analysts to confirm the accuracy of data filters and analytic routines. Analyses were performed using SAS (SAS/STAT User's Guide, Version 9.1, SAS, Inc, Cary NC), STATA ( StataCorp. 2013, Stata Statistical Software, Release 13, College Station, TX) and, R (The R Project for Statistical Computing, Version 2.11.1, available at: http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

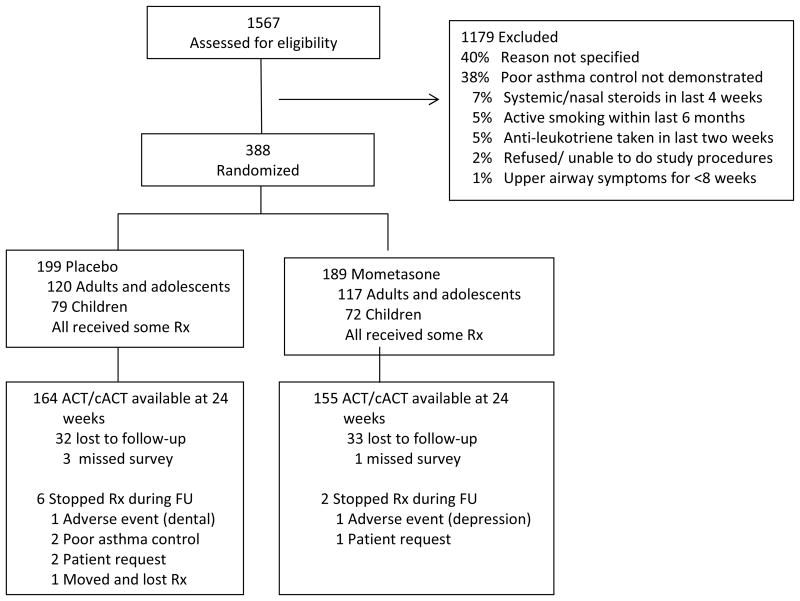

A total of 1567 participants were screened for eligibility (Figure 1). Three-hundred eighty-eight were randomized; 199 to placebo and 189 to mometasone. A similar number of adults (ages 18 and older) and children (ages 6-17) were randomized to both groups (120 adults and 79 children to placebo and 117 adults and 72 children to mometasone group). The lost to follow-up rate was similar in each group; 82% of participants completed the primary outcome questionnaire at week 24 and 90% of all follow-up visits were completed. Baseline characteristics of participants completing the study (n=319) were similar to those who did not complete the final visit (n=69) except for the fact that controller use was significantly higher in those who completed the study as compared to those who did not (74% vs 61%, p = 0.04) (Supplemental Table 1). Self-reported adherence to study treatments was high (> 90% of follow-up days) in both groups according to diary cards and interviews at study visits. Use of new sinus and new/increasing asthma medications was similar in placebo and mometasone groups (Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 1.

Eligibility screening, randomization and follow up of study participants. All patients were included in the analysis based upon the assigned treatment.

Rx = therapy; FU = follow-up.

Characteristics of study participants

Demographics, medication use, and measures of asthma and sinus disease were similar in both groups, though participants assigned to mometasone tended to have lower bronchial reactivity, indicated by a higher PC20, at baseline (Table I). By design, participants had poor asthma control with an ACT score of less than 19 required at enrollment, although some improved beyond that threshold by randomization. Many participants (28%) were not taking controller medication for their asthma, this was not a requirement for study participation.

Table I. Characteristics of the study population at randomization.

| Mometasone (N = 189) |

Placebo (N = 199) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age in years, Median (IQR) | 27 (12, 46) | 26 (12, 43) |

| Age categories, N (%) | ||

| Pediatric (6-11 years old) | 40 (21%) | 46 (23%) |

| Adolescent (12-17 years old) | 32 (17%) | 33 (17%) |

| Adult (18 and older) | 117 (62%) | 120 (60%) |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | ||

| White | 71 (38%) | 76 (38%) |

| Black | 74 (39%) | 73 (37%) |

| Hispanic | 35 (19%) | 46 (23%) |

| Other | 9 (5%) | 4 (2%) |

| Male, N (%) | 84 (44%) | 93 (47%) |

| Second-hand smoke exposure, N (%) | 50 (26%) | 42 (21%) |

| Atopy, N(%) | 137 (82%)†† | 149 (84%)†† |

| Asthma characteristics | ||

| Age of asthma onset, Median (IQR) | 5 (1, 13) | 4 (1, 12) |

| Emergency visits in the past 12 months, N (%) | 123 (65%) | 125 (63%) |

| Steroid bursts in the past 12 months, N (%) | 88 (47%) | 102 (51%) |

| Using controller medication, N (%)* | 134 (71%) | 144 (72%) |

| ICS in combination with LABA | 81 (43%) | 85 (43%) |

| ICS without LABA | 52 (28%) | 59 (30%) |

| Lung function, Median (IQR) | ||

| Pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (% predicted) | 85 (76, 96) | 85 (73, 95) |

| Pre-bronchodilator FVC (% predicted) | 96 (86, 106) | 95 (86, 105) |

| Pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC | 0.75 (0.70, 0.80) | 0.75 (0.68, 0.81) |

| Peak expiratory flow (L/min) | 340 (280, 420) | 350 (280, 430) |

| PC20 (mg/mL) | 2.29 (0.53, 6.11) | 0.67 (0.20, 3.01) |

| Questionnaires, Median (IQR) | ||

| ACT score (range: 5-25) ↑† | 16 (14, 19) | 17 (14, 18) |

| cACT score (range: 0-27)↑† | 17 (15, 19) | 17 (14, 18) |

| Asthma symptom utility index (range: 0-1) ↑‡ | 0.77 (0.69, 0.88) | 0.79 (0.69, 0.88) |

| Marks asthma quality of life questionnaire (range: 1-80)↓ § | 17 (10, 30) | 21 (11,31) |

| Children's health survey for asthma (range: 0-100)↑** | ||

| Physical health (child) | 77 (68, 87) | 77 (68, 87) |

| Activities (child) | 85 (65, 95) | 85 (65, 100) |

| Activities (family) | 96 (83, 100) | 92 (83, 100) |

| Emotional health (child) | 80 (65, 95) | 80 (55, 95) |

| Emotional health (family) | 79 (69, 90) | 78 (71, 90) |

| Sinus symptom score (range: 1-60) ↓‡ | 25 (17, 32) | 25 (16, 34) |

| SNOT-22 (range: 0-120)↓ § | 37 (23, 54) | 36 (21, 53) |

| SN-5 (range: 1-7)↓** | 3.3 (2.8, 4.0) | 3.8 (3.0, 4.6) |

One individual was using LABA without ICS in mometasone arm.

The ACT was administered to participants 12 years of age and older and the cACT was administered to participants aged 6 to 11 years.

The ASUI and SSS were administered to all participants.

The Marks asthma quality of life questionnaire and the SNOT-22 were administered to participants aged 18 and older.

The Children's health survey for asthma and the SN-5 were administered to participants ages 6 to 17 years.

A total of 168 participants in the mometasone and 178 participants in the placebo arm had valid skin testing data available. Thirty did not perform the test, 3 were missing data, and 9 did not have a valid test (i.e. the positive control was negative).

IQR = interquartile range; N = number; % = percent; ↑ = high scores indicate better health; ↓ = low scores indicate better health

Effect of treatment on asthma control

After 24 weeks of study treatment, there was no significant difference in the change in childhood asthma control score (children ages 6-11) between those assigned to mometasone and those assigned to placebo (difference in change in mometasone – change in placebo [ΔM - ΔP]: -0.38, CI: -2.19 to 1.44, p = 0.68) (Table II). Asthma control scores tended to improve over the course of the trial in both treatment groups (range: 1.81 to 4.53, p < 0.0001 at all time points) (Supplemental Figure E1a). Similarly, there was no difference in the asthma control test for adults and adolescents ( ages 12 and older) for those assigned to mometasone versus those assigned to placebo (Table II), and asthma control tended to improve in both treatment groups (range: 1.75 to 2.95, p < 0.0001 at all time points)(Supplemental Figure E1b).

Table II.

Comparison of the change in asthma control for participants treated with mometasone versus placebo at 4, 12, and 24 weeks. Asthma control was measured by ACT for adolescent and adult participants (ages 12 and older) and by cACT for pediatric participants (ages 6-11).

| N* | Change from randomization (SE) | Difference in change from randomization (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mometasone | Placebo | Mometasone – Placebo | |||

| cACT: Pediatric (ages 6-11) ↑ | |||||

| Week 4 | 82 | 1.81 (0.58) | 2.69 (0.54) | -0.88 (-2.47 ,0.71) | 0.27 |

| Week 12 | 75 | 3.40 (0.61) | 3.05 (0.71) | 0.34 (-1.52 ,2.21) | 0.71 |

| Week 24 | 71 | 4.15 (0.64) | 4.53 (0.65) | -0.38 (-2.19 ,1.44) | 0.68 |

| ACT: Adolescent and adult (ages 12 and over) ↑ | |||||

| Week 4 | 277 | 1.89 (0.26) | 1.75 (0.31) | 0.14 (-0.66 ,0.94) | 0.72 |

| Week 12 | 262 | 2.69 (0.30) | 2.25 (0.32) | 0.44 (-0.43 ,1.31) | 0.32 |

| Week 24 | 248 | 2.95 (0.31) | 2.44 (0.38) | 0.51 (-0.46 ,1.48) | 0.30 |

N is the number of participants with follow-up at each time point (4, 12, and 24 weeks).

SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval; ↑ = an increase indicates improved control.

Effect of treatment in children (ages 6-17) with poorly controlled asthma

There was no significant difference in the change in asthma symptoms, asthma quality of life, sinus symptom scores, or exhaled nitric oxide at 24 weeks compared to baseline in children assigned to placebo versus those assigned to mometasone (Table III). There was a small difference in improvement in lung function measured by FEV1 (ΔM - ΔP: 3.45, 95% CI: -0.52 to 7.42), and some evidence of larger improvement in forced vital capacity in children assigned to mometasone (ΔM - ΔP: 2.44, 95% CI: -0.60 to 5.48), although neither was statistically significant (p = 0.09 and 0.12, respectively). The percent improvement in PC20 was similar for both treatments (test of interaction: p = 0.52) at 89% (95% CI: 37% to 159%). There was a lower rate of episodes of poor asthma control (rate ratio 0.64, p=0.04) in children assigned to mometasone versus placebo. The effect was primarily driven by lower rates of episodes of decreased peak flow, defined as a 30% decrease in peak flow for two consecutive days (rate ratio 0.44, p = 0.03). No differences in the other components of episodes of poor asthma control, i.e., urgent care visits, use of systemic steroids, or use of rescue medications were noted (Table IV). In post-hoc analyses, we did not find any suggestion of a sub-group, as defined by gender, controller medication use or atopic status, that benefited from nasal steroids in this 24 week treatment trial.

Table III.

Twenty-four week change in asthma symptoms, lung function, and sinus symptoms in children (ages 6-17) treated with mometasone versus placebo.

| N | Change from randomization (SE) |

Difference in change from randomization (95% CI) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mometasone | Placebo | Mometasone - Placebo | |||

| Asthma Symptom Utility Index | 126 | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.1 (0.02) | -0.06 (-0.13 ,0.01) | 0.07 |

| Childhood health survey for asthma | |||||

| Physical health | 123 | 6.37 (1.63) | 7.33 (1.59) | -0.95 (-5.45 ,3.55) | 0.68 |

| Activities (child) | 125 | 7.41 (2.03) | 5.95 (2.38) | 1.45 (-4.74 ,7.65) | 0.64 |

| Activities (family) | 125 | 2.09 (1.74) | 5.35 (1.43) | -3.26 (-7.72 ,1.20) | 0.15 |

| Emotional health (child) | 125 | 3.87 (2.83) | 7.35 (2.46) | -3.48 (-10.91 ,3.94) | 0.36 |

| Emotional health (family) | 123 | 4.01 (1.61) | 3.26 (1.55) | 0.76 (-3.66 ,5.18) | 0.74 |

| Lung function | |||||

| Pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (% predicted) | 127 | 2.62 (1.68) | -0.83 (1.1) | 3.45 (-0.52 ,7.42) | 0.09 |

| Pre-bronchodilator FVC (% predicted) | 127 | 2.1 (1.24) | -0.34 (0.92) | 2.44 (-0.60 ,5.48) | 0.12 |

| FEV1/FVC | 127 | 0.007 (0.009) | -0.007 (0.006) | 0.013 (-0.009 ,0.035) | 0.23 |

| FeNO (ppb)* | 123 | 10.92 (5.34) | 5.65 (2.89) | 5.28 (-6.72, 17.28) | 0.39 |

| Sinus symptoms | |||||

| Sinus Symptom Score | 127 | -7.38 (1.38) | -7.38 (1.43) | -0.004 (-3.94 ,3.93) | > 0.99 |

| SN-5 | 126 | -0.76 (0.12) | -0.98 (0.14) | 0.22 (-0.14, 0.59) | 0.22 |

FeNO was measured at baseline and at 24 weeks.

N = number of participants evaluable at 24 weeks; CI = confidence interval; Δ = change. I

Table IV.

Episodes of Poor Asthma control in children (ages 6-17) treated with mometasone versus placebo.

| Episodes of poor asthma control | Treatment Assignment | Rate Ratio (95% CI)* Mometasome / Placebo |

P-value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mometasone (N = 66) |

Placebo (N =75) |

||||||

|

| |||||||

| Overall | |||||||

| Patients with ≥ 1 event, N (%) | 36 (55%) | 42 (56%) | |||||

| Number of events | 73 | 128 | |||||

| Annual per-person event rate (95% CI) | 2.7 (2.1, 3.6) | 4.2 (3.1, 5.8) | 0.64 (0.42, 0.97) | 0.04 | |||

| Individual components | |||||||

| Drop in peak flow of ≥ 30 % for 2 consecutive days | |||||||

| Patients with ≥ 1 event, N (%) | 14 (21%) | 20 (27%) | |||||

| Number of events | 30 | 73 | |||||

| Annual per-person event rate (95% CI) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.9) | 2.5 (1.5, 4.2) | 0.44 (0.22, 0.90) | 0.03 | |||

| Urgent asthma care | |||||||

| Patients with ≥ 1 event, N (%) | 15 (22%) | 10 (13%) | |||||

| Number of events | 18 | 12 | |||||

| Annual per-person event rate (95% CI) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.1) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.7) | 1.75 (0.81, 3.80) | 0.15 | |||

| Systemic steroids | |||||||

| Patients with ≥ 1 event, N (%) | 13 (20%) | 13 (17%) | |||||

| Number of events | 13 | 13 | |||||

| Annual per-person event rate (95% CI) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) | 0.4 (0.3, 0.7) | 1.17 (0.57, 2.36) | 0.67 | |||

| Increased Rescue Medications | |||||||

| Patients with ≥ 1 event, N (%) | 27 (44%) | 27 (38%) | |||||

| Number of events | 47 | 67 | |||||

| Annual per-person event rate (95% CI) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) | 2.3 (1.5, 3.4) | 0.82 (0.49, 1.39) | 0.44 | |||

Rate Ratios, 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) and P-values are based on negative binomial regression.

Effect of treatment in adults (ages 18 and older) with poorly controlled asthma

There was a statistically significant improvement in the change in Asthma Symptom Utility Index at 24 weeks compared to baseline in adults assigned to mometasone versus placebo (ΔM - ΔP: 0.06, 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.11, p = 0.0095, Table V). There was no difference in the change in asthma quality of life, lung function or exhaled nitric oxide in those assigned to mometasone versus placebo. There was a significant greater decrease in the sinus symptom score in those assigned to mometasone (ΔM - ΔP: -3.82, 95% CI: -7.19 to -0.45, p = 0.026) as well as the change in SNOT-22 score (ΔM - ΔP: -4.83, 95% CI: -9.86 to 0.21), though the latter did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.06). Although the PC20 was higher at baseline for those treated with mometasone versus those treated with placebo (geometric mean: 1.64 vs. 0.77 (a difference that was statistically significant (p = 0.004)), there was not a significant difference in the percent change from baseline for the two groups (p = 0.42) with an overall improvement of 58% (95% CI: 19% to 111%, p = 0.002). There was no difference in the rate of episodes of poor asthma control in those assigned to mometasone versus placebo overall (p = 0.92, Table VI). In post-hoc analyses, we did not find any suggestion of a sub-group, as defined by gender, controller medication use or atopic status, that benefited from nasal steroids in this 24 week treatment trial.

Table V.

Twenty-four week change in asthma symptoms, lung function, and sinus symptoms in adults (ages 18 and older) treated with mometasone versus placebo.

| N | Change from randomization (SE) |

Difference in change from randomization (95% CI) |

P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mometasone | Placebo | Mometasone - Placebo | ||||||

| Asthma Symptom Utility Index | 193 | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.01 ,0.11) | < 0.01 | |||

| Marks asthma quality of life questionnaire | 192 | -5.26 (1.11) | -5.48 (1.06) | 0.22 (-2.82 ,3.26) | 0.89 | |||

| Lung function | ||||||||

| Pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (% predicted) | 193 | -1.40 (1.07) | 0.51 (0.97) | -1.91 (-4.76 ,0.94) | 0.18 | |||

| Pre-bronchodilator FVC (% predicted) | 193 | -1.27 (0.95) | 0.06 (0.85) | -1.33 (-3.85 ,1.19) | 0.30 | |||

| FEV1/FVC | 193 | -0.001 (0.004) | 0.004 (0.004) | -0.005 (-0.017 ,0.008) | 0.43 | |||

| FeNO (ppb)* | 183 | -0.08 (1.98) | -0.02 (2.96) | -0.06 (-7.08, 6.96) | 0.99 | |||

| Sinus symptoms | ||||||||

| Sinus Symptom Score | 194 | -9.46 (1.18) | -5.64 (1.24) | -3.82 (-7.19 ,-0.45) | 0.03 | |||

| SN-22 | 193 | -11.2 (1.86) | -6.37 (1.75) | -4.83 (-9.86 ,0.21) | 0.06 | |||

FeNO was measured at baseline and at 24 weeks.

N = number of participants evaluable at 24 weeks; CI = confidence interval.

Table VI.

Asthma symptoms, lung function and sinus symptoms in adults (ages 18 and older) treated with mometasone versus placebo.

| Treatment Assignment | Rate Ratio (95% CI)* Mometasome / Placebo |

P-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mometasone (N = 111) |

Placebo (N = 111) |

|||

|

| ||||

| Episodes of poor asthma control, overall | ||||

| Patients with ≥ 1 event, N (%) | 45 (41%) | 48 (43%) | ||

| Number of events | 104 | 114 | ||

| Annual per-person event rate (95% CI) | 2.5 (1.9, 3.5) | 2.6 (1.9, 3.5) | 0.98 (0.64, 1.51) | 0.92 |

| Episodes of poor asthma control, components | ||||

| Drop in peak flow of ≥ 30 % for 2 consecutive days | ||||

| Patients with ≥ 1 event, N (%) | 14 (21%) | 20 (27%) | ||

| Number of events | 38 | 68 | ||

| Annual per-person event rate (95% CI) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.5) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.6) | 0.55 (0.27, 1.10) | 0.09 |

| Urgent asthma care | ||||

| Patients with ≥ 1 event, N (%) | 6 (5%) | 11 (9%) | ||

| Number of events | 6 | 14 | ||

| Annual per-person event rate (95% CI) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.3) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.6) | 0.45 (0.16, 1.27) | 0.13 |

| Systemic steroids | ||||

| Patients with ≥ 1 event, N (%) | 15 (14%) | 17 (15%) | ||

| Number of events | 20 | 15 | ||

| Annual per-person event rate (95% CI) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.5) | 0.4 (0.3, 0.7) | 0.78 (0.40, 1.52) | 0.47 |

| Increased Rescue Medications | ||||

| Patients with ≥ 1 event, N (%) | 29 (28%) | 27 (26%) | ||

| Number of events | 62 | 49 | ||

| Annual per-person event rate (95% CI) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.5) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.9) | 1.42 (0.78, 2.59) | 0.25 |

Rate Ratios, 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) and p-values are based on negative binomial regression.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that treatment of chronic sinonasal disease for 24 weeks does not improve asthma control in children or adults with inadequately controlled asthma. This study is unique in that it included a diverse patient population of adults and children with inadequately controlled asthma, and we studied the effect of nasal corticosteroids over a 24-week time period. The results of this study have important implications for the treatment of patients with asthma.

Sinonasal disease has been associated with severe asthma, and treatment of sinonasal disease is frequently advocated to improve asthma control. However, our current study provides important new insights into our understanding of the relationship between sinonasal disease and asthma, significantly expanding on previous studies. There have been many observational and small single center studies published on the effectiveness of treatment of sinonasal disease for the control of asthma in patients with sinonasal disease and asthma. Some small studies suggest that short term treatment of seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis improves airway reactivity in patients with asthma,15,33 while others do not.34 Recently there have been a few multi-center trials investigating the short-term effects of treating sinonasal disease in asthma. Dahl et al found no effect of 6 weeks of nasal corticosteroids on airway reactivity or induced sputum eosinophilia;16 Katial et al and Nathan et al found that 4 weeks of intranasal corticosteroids improved nasal symptoms, but had no effect on asthma control.35,36 These prior trials have studied the short-term efficacy of nasal corticosteroids in asthma, and suggest that the short-term treatment of sinonasal disease with nasal corticosteroids does not improve asthma outcomes. There have been very few prospective, controlled studies of longer term treatment of sinonasal disease in asthma. In one longer-term (16 week) single center study, Stelmach et al found that patients with allergic rhinitis and asthma had decreased pulmonary symptoms over the course of the study when treated with nasal corticosteroids; however there was no placebo group and all patient groups improved over the course of the study, as occurred in our own study.37 Our trial is unique in that we measured the effects of nasal steroid compared with placebo over a longer time period (24 week) in both adults and children with chronic disease and poor asthma control. Our study shows that chronic nasal corticosteroids do not have a significant effect on asthma control.

We did find a small improvement in lung function in children assigned to nasal mometasone. This improvement was not simply in children not using controller medication. It may be that the added dose of nasal steroid was beneficial for lung function either through systemic effects or perhaps post nasal drip of corticosteroids. However, the clinical significance of this small improvement in lung function is uncertain.

We did see fewer episodes of two consecutive days with decrease in peak flow of ≥ 30 % in children. The reason for this is not known, though we speculate this may be related to some effect of post-nasal drip in the large airways. However, the clinical significance of this is uncertain given that it did not translate into improved asthma control, and was not associated with other more clinically significant markers of asthma exacerbations.

As anticipated, we did find that nasal corticosteroids improved sinus symptoms, and tended to improve quality of life related to sinus disease in adults. We did not see any improvement in sinus disease symptoms in children. The questionnaire we used to screen for sinonasal disease was developed in adults, but other measures of sinonasal disease gave scores similar to those previously reported for children with chronic rhinosinutis and perennial rhinitis, suggesting the study group had significant disease that could respond to intervention.29,38-42 This lack of improvement was unexpected given that previous studies show nasal mometasone in the dose used in this study is effective for the treatment of rhinitis in children,43 and nasal corticosteroids are considered first line therapy for the treatment of sinonasal disease in children.44 Although we do not know the reason for the lack of improvement, it is possible that adherence or drug delivery was more challenging in children than adults. Adherence in this study was monitored from diary cards and appeared to be the same in adults and children (greater than 90%), but this was by self-report and so may be subject to reporter bias. The fact that we did see some improvement in lung function in children assigned to nasal mometasone would also suggest that the children were using this medication, though it is possible that the drug was not being correctly delivered in children compared with adults.

We included both rhinitis and sinusitis in this trial, rather than trying to separate out the two. Asthma, rhinitis and sinusitis share a common pathophysiology with common inflammatory mediators and histopathological changes apparent in the upper and lower airways.45 Rhinitis and sinusitis in asthma represent a disease continuum of the upper airway, which may be difficult to separate out without invasive testing, and so we did not attempt to distinguish the two.

The strengths of this study are that it was a large multi-center trial that enrolled a diverse patient population. It was of longer duration than prior studies, and so adds significantly to the previous literature. This study used a pragmatic design with regard to pre-existing asthma medications, which will enhance its applicability to a broad patient population. We assessed various sub-groups in post-hoc analyses (including atopic versus non-atopic participants, and participants on controller therapy versus those not on controller therapy), and did not find a sub-group that benefited from nasal steroids in terms of asthma control. We did not address whether treating acute and/or severe disease would improve asthma outcomes, but as these require treatment anyway, this is more compelling as a scientific than as a clinical question

In conclusion, this investigation shows that long term treatment with nasal corticosteroids does not improve asthma control in adults or children with inadequately controlled asthma. Sinonasal disease may be associated with severe asthma,46,47 but the efficacy of treating sinonasal disease as a treatment modality for asthma alone is not supported by the current literature. Disease in the upper and lower airway may parallel one another in terms of severity, but treating one and to improve the other is of limited effectiveness.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure E1: Asthma control during study treatment for participants assigned to mometasone and placebo for (a) participants ages 6-11 years measured by the Childhood Asthma Control Test and for (b) participants for participants 12 years of age and older measured by the Asthma Control Test.

Supplemental Table 1: Characteristics of the study population at randomization stratified by availability of the ACT or cACT questionnaire at 24 weeks.

ST2: New Sinus and new/increasing asthma medication use during treatment period of trial

Clinical Implications.

Treatment of chronic sinonasal disease with nasal corticosteroids does not improve asthma control.

Acknowledgments

American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers (a full listing of the center investigators is in the online supplement): Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas; Columbia University–New York University Consortium, New York; Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina; Illinois Consortium, Chicago, Illinois; Indiana University, Indianapolis, Indiana; Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, Louisiana; National Jewish Health, Denver, Colorado; Nemours Children's Clinic–University of Florida Consortium, Jacksonville, Florida; Hofstra North Shore-Long-Island Jewish School of Medicine, New Hyde Park, New York; University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont; The Ohio State University Medical Center/Columbus Children's Hospital, Columbus, Ohio; Maria Fareri Children's Hospital at Westchester Medical Center and New York Medical College, New York; Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri; University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona; University of Miami, Miami–University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida; University of Missouri, Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City, Missouri; University of California San Diego, California; University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Chairman's Office University of Alabama, Birmingham (formerly at Respiratory Hospital, Winnipeg, Man., Canada): William C. Bailey, MD and Nicholas Anthonisen, MD, PhD (research group chair);

Data Coordinating Center, Johns Hopkins University Center for Clinical Trials, Baltimore

Data and Safety Monitoring Board: Stephen C. Lazarus, MD (chair), William J. Calhoun, MD, Michelle Cloutier, MD, Peter Kahrilas, MD, Bennie McWilliams, MD, Andre Rogatko, PhD, Christine Sorkness, PharmD; The DSMB had a role in the review of the study and reviewed a preliminary draft of the final manuscript.

Project Office, American Lung Association, New York: Elizabeth Lancet, MPH (project officer), Norman Edelman, MD (scientific consultant), Susan Rappaport, MPH; The sponsor had a role in the management and review of the study.

CREDIT ROSTER

American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston: Nicola Hanania, MD, FCCP (principal investigator), Marianna Sockrider, MD, DrPH (co-principal investigator), Laura Bertrand, RN, RPFT (principal clinic coordinator), Mustafa A. Atik, MD (coordinator).

Former Members: Blanca A. Lopez, LVN.

Columbia University–New York University Consortium, New York: Joan Reibman, MD (principal investigator), Emily DiMango, MD, Linda Rogers, MD (co-principal investigators), Karen Carapetyan, MA (clinic coordinator at New York University), Kristina Rivera, MPH, Newel Bryce-Robinson, Melissa Scheuerman (clinic coordinators at Columbia University).

Former Members: Elizabeth Fiorino, MD.

Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.: John Sundy, MD, PhD (principal investigator), Brian Vickery, MD, Deanna Green, MD, Eveline Wu, MD (co-principal investigators), Catherine Foss, BS, RRT, CCRC (principal clinic coordinator), Jessica Ghidorzi, Sabrena Mervin-Blake, Elise Pangborn, V. Susan Robertson, Nicholas Eberlein, Stephanie Allen (coordinators).

Former Members: Michael Land, MD.

Illinois Consortium, Chicago: Lewis Smith, MD (principal investigator), Ravi Kalhan, MD, James Moy, MD, Mary Nevin, Edward Naureckas, MD (co-principal investigators), Jenny Hixon, BS, CCRC (principal clinic coordinator), Abbi Brees, BA, CCRC, Zenobia Gonsalves, Virginia Zagaja, Jennifer Kustwin, Ben Xu, BS, CCRC, Thomas Matthews, MPH, RRT, Lucius Robinson, Noopur Singh (coordinators).

Former Members:

Indiana University, Asthma Clinical Research Center, Indianapolis: Michael Busk, MD, MPH (principal investigator), Paula Puntenney, RN, MA (principal clinic coordinator), Nancy Busk, BS, MS, Janet Hutchins, BSN (coordinators).

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, The Ernest N. Morial Asthma, Allergy and Respiratory Disease Center: Kyle I. Happel, MD (principal investigator), Richard S. Tejedor, MD (co-principal investigator), Marie C. Sandi, RN, MN, FNP-BC (principal clinic coordinator), Connie Romaine, RN, FNP, Callan J. Burzynski , Jonathan Cruse (coordinators).

Former Members: Arleen Antoine.

National Jewish Health, Denver: Rohit Katial, MD (principal investigator), Flavia C. Hoyte, MD, Dan Searing, MD (co-principal investigators), Trisha Larson (principal clinic coordinator), Nina Thompson (recruiter), Michael P. White (coordinator).

Former Members: Holly Currier, RN.

Nemours Children's Clinic–University of Florida Consortium, Jacksonville: John Lima, PharmD (principal investigator), Kathryn Blake, PharmD (co-principal investigator), Jason Lang, MD (co-principal investigator), Deanna Seymour, RN, BSN (principal coordinator), Nancy Archer, RN, BSN (coordinator).

Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine, Beth Thalheim Asthma Center (formerly North Shore–Long Island Jewish Health System), New Hyde Park, N.Y.: Rubin Cohen, MD (principal investigator), Maria Santiago, MD (co-principal investigator), Ramona Ramdeo, MSN, FNP-C, RN, RT (principal clinic coordinator).

Vermont Lung Center at the University of Vermont, Colchester, Vt.: Charles Irvin, PhD (principal investigator), Anne E. Dixon, MD, David A. Kaminsky, MD, Thomas Lahiri, MD (co-investigators), Stephanie M. Burns (principal clinic coordinator), Kendall Black.

The Ohio State University Medical Center/Columbus Children's Hospital, Columbus: John Mastronarde, MD (principal investigator), Jonathan Parsons, MD (co-investigator), Janice Drake, CCRC (principal clinic coordinator), Joseph Santiago, BS (coordinator).

Former Members: David Cosmar, BA, Rachael A. Compton (coordinators).

Maria Fareri Children's Hospital at Westchester Medical Center and New York Medical College: Allen J. Dozor, MD (principal investigator), Sankaran Krishnan, MD, MPH, Joseph Boyer, MD (co-investigators), Agnes Banquet, MD, Elizabeth de la Riva-Velasco, MD, Diana Lowenthal, MD, Suzette Gjonaj, MD, Y. Cathy Kim, MD, Nadav Traeger, MD, John Welter, MD, Marilyn Scharbach, MD, Subhadra Siegel, MD (study physicians), Ingrid Gherson, MPH (lead research coordinator), Lisa Monchil, RRT, CCRC, Aliza Goldstein, BA (research coordinators), Tara M. Formisano, BS, Patrick H. Frangos, Jillian Jones, BSN, PNP, Jessica Williams (data entry personnel).

St. Louis Asthma Clinical Research Center: Washington University, St. Louis: Mario Castro, MD, MPH (principal investigator), Leonard Bacharier, MD, Kaharu Sumino, MD, Raymond Slavin, MD (co-investigators), Jaime J. Tarsi, RN, MPH (principal coordinator), Brenda Patterson, MSN, RN, FNP, Deborah Keaney (coordinators), Terri Montgomery.

University of Arizona, Tucson: Lynn B. Gerald, PhD, MSPH (principal investigator), James L. Goodwin, PhD, Mark A. Brown, MD, Kenneth S. Knox, MD (co-principal investigators), Tara F. Carr, MD, Cristine E. Berry, MD, MHS, Fernando D. Martinez, MD, Wayne J. Morgan, MD, Cori L. Daines, MD, Michael O. Daines, MD, Roni Grad, MD, Dima Ezmigna, MBBS (study physicians), Monica M. Vasquez, MPH, MEd (principal clinic coordinator), Jesus A. Wences, BS, Silvia S. Lopez, RN, Janette C. Priefert (coordinators).

Former Members: Monica T. Varela, LPN, Rosemary J. Weese, RN, RRT (coordinators), Katherine Chee, Andrea Paco (data entry personnel).

University of Miami, Miami–University of South Florida, Tampa: Adam Wanner, MD (principal investigator, Miami), Richard Lockey, MD (principal investigator, Tampa), Michael Campos, MD, Andreas Schmid, MD (co-investigators, Miami), Dr. Monroe King (co-investigator, Tampa), Eliana S. Mendes, MD (principal clinic coordinator for University of Miami), Patricia D. Rebolledo, Johana Arana, Lilian Cadet, Rebecca McCrery, Sarah M. Croker, BA (coordinators).

Former Members: Shirley McCullough, BS, LPN (coordinator).

University of Missouri, Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City: Gary Salzman, MD (principal investigator), Chitra Dinakar, MD, Asem Abdeljalil, MD, Dennis Pyszczynski, MD, Abid Bhat, MD (co-investigators), Patti Haney, RN, BSN, CCRC (principal clinic coordinator), Susan Flack, RN, CCRC, Donna Horner, LPN, CCRC (coordinators).

University of California San Diego: Stephen Wasserman, MD (principal investigator), Joe Ramsdell, MD, Xaiver Soler, MD, PhD (co-principal investigators), Katie Kinninger, RCP (principal clinic coordinator), Paul Ferguson, MS, Amber Martineau, Samang Ung (coordinators).

Former Members: Tonya Greene (clinic coordinator).

University of Virginia, Charlottesville: W. Gerald Teague, MD (principal investigator), Kristin W. Wavell, BS (principal coordinator).

Former Members: Donna Wolf, PhD, Denise Thompson-Batt, RRT, CRP (coordinators).

Data Coordinating Center, Johns Hopkins University Center for Clinical Trials, Baltimore: Robert Wise, MD (center director), Janet Holbrook, PhD, MPH (deputy director), Sobharani Rayapudi, MD, ScM (principal coordinator), Debra Amend-Libercci, Anna Adler, Christian Bime, MD, MSc, Anne Shanklin Casper, MA, Marie Daniel, BA, Adante Hart, Andrea Lears, BS, Gwen Leatherman, BSN, MS, RN, Deborah Nowakowski, Nancy Prusakowski, MS, Alexis Rea, Joy Saams, RN, David Shade, JD, Elizabeth Sugar, PhD, April Thurman, Christine Wei, MS, Razan Yasin, MHS.

Former Members: Ellen Brown, MS, Charlene Levine, BS, Suzanna Roettger, MA, Paul Chen, Nien-Chun Wu, Lucy Wang, Johnson Ukken, BA.

Supported by grants from the National Heart Blood and Lung Institute (UO1HL089464 and U01 HL089510, UL1 TR000448) and the American Lung Association. Study drug and placebo provided by Merck

Abbreviations

- ASUI

Asthma Symptom Utility Index

- ACT

Asthma Control Test

- cACT

Childhood Asthma Control Test

- CHSA

childhood health survey for asthma

- FeNO

exhaled nitric oxide

- PEF

peak expiratory flow rate

- PC20

mg/ml methacholine which causes a 20% fall in FEV1

- SNOT 22

Sino Nasal Outcomes Test 22

- SN5

Sino Nasal survey 5

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Thomas M, Kocevar VS, Zhang Q, et al. Asthma-related health care resource use among asthmatic children with and without concomitant allergic rhinitis. Pediatrics. 2005;115:129–134. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sazonov Kocevar V, Thomas J, 3rd, Jonsson L, et al. Association between allergic rhinitis and hospital resource use among asthmatic children in Norway. Allergy. 2005;60:338–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bousquet J, Boushey HA, Busse WW, et al. Characteristics of patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis and concomitant asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:897–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ten Brinke A, Grootendorst DC, Schmidt JT, et al. Chronic sinusitis in severe asthma is related to sputum eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:621–626. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.122458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bresciani M, Paradis L, Des Roches A, et al. Rhinosinusitis in severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:73–80. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.111593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon AE, Kaminsky DA, Holbrook JT, et al. Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis in asthma: differential effects on symptoms and pulmonary function. Chest. 2006;130:429–435. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plaschke PP, Janson C, Norrman E, et al. Onset and remission of allergic rhinitis and asthma and the relationship with atopic sensitization and smoking. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:920–924. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9912030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonay M, Neukirch C, Grandsaigne M, et al. Changes in airway inflammation following nasal allergic challenge in patients with seasonal rhinitis. Allergy. 2006;61:111–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braunstahl GJ, Kleinjan A, Overbeek SE, et al. Segmental bronchial provocation induces nasal inflammation in allergic rhinitis patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:2051–2057. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9906121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brugman SM, Larsen GL, Henson PM, et al. Increased lower airways responsiveness associated with sinusitis in a rabbit model. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:314–320. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nolte D, Berger D. On vagal bronchoconstriction in asthmatic patients by nasal irritation. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1983;128(Pt 1):110–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ragab S, Scadding GK, Lund VJ, et al. Treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis and its effects on asthma. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:68–74. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00043305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunlop G, Scadding GK, Lund VJ. The effect of endoscopic sinus surgery on asthma: management of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, nasal polyposis, and asthma. Am J Rhinol. 1999;13:261–265. doi: 10.2500/105065899782102809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aubier M, Levy J, Clerici C, et al. Different effects of nasal and bronchial glucocorticosteroid administration on bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with allergic rhinitis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:122–126. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corren J, Adinoff AD, Buchmeier AD, et al. Nasal beclomethasone prevents the seasonal increase in bronchial responsiveness in patients with allergic rhinitis and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90:250–256. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90079-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahl R, Nielsen LP, Kips J, et al. Intranasal and inhaled fluticasone propionate for pollen- induced rhinitis and asthma. Allergy. 2005;60:875–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thio BJ, Slingerland GL, Fredriks AM, et al. Influence of intranasal steroids during the grass pollen season on bronchial responsiveness in children and young adults with asthma and hay fever. Thorax. 2000;55:826–832. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.10.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corren J, Manning BE, Thompson SF, et al. Rhinitis therapy and the prevention of hospital care for asthma: a case-control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taegtmeyer AB, Steurer-Stey C, Spertini F, et al. Allergic rhinitis in patients with asthma: the Swiss LARA (Link Allergic Rhinitis in Asthma) survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:1073–1080. doi: 10.1185/03007990902820733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dixon AE, Sugar EA, Zinreich SJ, et al. Criteria to screen for chronic sinonasal disease. Chest. 2009;136:1324–1332. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu AH, Zeiger R, Sorkness C, et al. Development and cross-sectional validation of the Childhood Asthma Control Test. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:817–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schatz M, Sorkness CA, Li JT, et al. Asthma Control Test: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1107–1136. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Revicki DA, Leidy NK, Brennan-Diemer F, et al. Integrating patient preferences into health outcomes assessment: the multiattribute Asthma Symptom Utility Index. Chest. 1998;114:998–1007. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.4.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asmussen L, Olson LM, Grant EN, et al. Reliability and validity of the Children's Health Survey for Asthma. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e71. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.6.e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marks GB, Dunn SM, Woolcock AJ. A scale for the measurement of quality of life in adults with asthma. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:461–472. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker FD, White PS. Sinus symptom scores: what is the range in healthy individuals? Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2000;25:482–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2000.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kay DJ, Rosenfeld RM. Quality of life for children with persistent sinonasal symptoms. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:17–26. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2003.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hopkins C, Gillett S, Slack R, et al. Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34:447–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Writing Committee for the American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research C. Holbrook JT, Wise RA, et al. Lansoprazole for children with poorly controlled asthma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:373–381. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schatz M, Kosinski M, Yarlas AS, et al. The minimally important difference of the Asthma Control Test. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:719–723. e711. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watson WT, Becker AB, Simons FE. Treatment of allergic rhinitis with intranasal corticosteroids in patients with mild asthma: effect on lower airway responsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;91:97–101. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90301-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedroletti C, Lundahl J, Alving K, et al. Effect of nasal steroid treatment on airway inflammation determined by exhaled nitric oxide in allergic schoolchildren with perennial rhinitis and asthma. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:219–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katial RK, Oppenheimer JJ, Ostrom NK, et al. Adding montelukast to fluticasone propionate/salmeterol for control of asthma and seasonal allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:68–75. doi: 10.2500/aap.2010.31.3306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nathan RA, Yancey SW, Waitkus-Edwards K, et al. Fluticasone propionate nasal spray is superior to montelukast for allergic rhinitis while neither affects overall asthma control. Chest. 2005;128:1910–1920. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stelmach R, do Patrocinio TNM, Ribeiro M, et al. Effect of treating allergic rhinitis with corticosteroids in patients with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma. Chest. 2005;128:3140–3147. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abdalla S, Alreefy H, Hopkins C. Prevalence of sinonasal outcome test (SNOT-22) symptoms in patients undergoing surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis in the England and Wales National prospective audit. Clin Otolaryngol. 2012;37:276–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2012.02527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raithatha R, Anand VK, Mace JC, et al. Interrater agreement of nasal endoscopy for chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012;2:144–150. doi: 10.1002/alr.21009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillett S, Hopkins C, Slack R, et al. A pilot study of the SNOT 22 score in adults with no sinonasal disease. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34:467–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Passariello A, Di Costanzo M, Terrin G, et al. Crenotherapy modulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and immunoregulatory peptides in nasal secretions of children with chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26:e15–19. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erwin EA, Faust RA, Platts-Mills TA, et al. Epidemiological analysis of chronic rhinitis in pediatric patients. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011;25:327–332. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meltzer EO, Baena-Cagnani CE, Gates D, et al. Relieving nasal congestion in children with seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis: efficacy and safety studies of mometasone furoate nasal spray. World Allergy Organ J. 2013;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1939-4551-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Georgalas C, Terreehorst I, Fokkens W. Current management of allergic rhinitis in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21:e119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Togias A. Rhinitis and asthma: evidence for respiratory system integration. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1171–1183. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1592. quiz 1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.ten Brinke A, Sterk PJ, Masclee AA, et al. Risk factors of frequent exacerbations in difficult- to-treat asthma. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:812–818. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00037905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bousquet J, Gaugris S, Kocevar VS, et al. Increased risk of asthma attacks and emergency visits among asthma patients with allergic rhinitis: a subgroup analysis of the investigation of montelukast as a partner agent for complementary therapy [corrected] Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:723–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure E1: Asthma control during study treatment for participants assigned to mometasone and placebo for (a) participants ages 6-11 years measured by the Childhood Asthma Control Test and for (b) participants for participants 12 years of age and older measured by the Asthma Control Test.

Supplemental Table 1: Characteristics of the study population at randomization stratified by availability of the ACT or cACT questionnaire at 24 weeks.

ST2: New Sinus and new/increasing asthma medication use during treatment period of trial