Abstract

Objective:

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and conduct disorder (CD) are among the most common psychiatric diagnoses in childhood. Aggression and conduct problems are a major source of disability and a risk factor for poor long-term outcomes.

Methods:

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of antipsychotics, lithium, and anticonvulsants for aggression and conduct problems in youth with ADHD, ODD, and CD. Each medication was given an overall quality of evidence rating based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach.

Results:

Eleven RCTs of antipsychotics and 7 RCTs of lithium and anticonvulsants were included. There is moderate-quality evidence that risperidone has a moderate-to-large effect on conduct problems and aggression in youth with subaverage IQ and ODD, CD, or disruptive behaviour disorder not otherwise specified, with and without ADHD, and high-quality evidence that risperidone has a moderate effect on disruptive and aggressive behaviour in youth with average IQ and ODD or CD, with and without ADHD. Evidence supporting the use of haloperidol, thioridazine, quetiapine, and lithium in aggressive youth with CD is of low or very-low quality, and evidence supporting the use of divalproex in aggressive youth with ODD or CD is of low quality. There is very-low-quality evidence that carbamazepine is no different from placebo for the management of aggression in youth with CD.

Conclusion:

With the exception of risperidone, the evidence to support the use of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers is of low quality.

Keywords: antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, children, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, systematic review, meta-analysis

Abstract

Objectif :

Le trouble de déficit de l’attention avec hyperactivité (TDAH), le trouble oppositionnel avec provocation (TOP) et le trouble des conduites (TC) sont parmi les diagnostics psychiatriques les plus communs dans l’enfance. L’agressivité et les problèmes de conduite sont une source majeure d’incapacité et un facteur de risque de mauvais résultats à long terme.

Méthodes :

Nous avons effectué une revue systématique et une méta-analyse des essais randomisés contrôlés (ERC) d’antipsychotiques, de lithium, et d’anticonvulsivants pour l’agressivité et les problèmes de conduite chez des adolescents souffrant du TDAH, du TOP et du TC. Chaque médicament a reçu une qualité globale de classement des données probantes, selon l’approche de classement de l’analyse, de l’élaboration et de l’évaluation des recommandations.

Résultats :

Onze ERC d’antipsychotiques et 7 ERC de lithium et d’anticonvulsivants ont été inclus. Des données probantes de qualité modérée indiquent que la rispéridone a un effet de modéré à grand sur les problèmes de conduite et l’agressivité chez les adolescents ayant un QI sous la moyenne et un TOP, un TC ou un trouble de comportement perturbateur non spécifié, avec et sans TDAH. Des données probantes de qualité élevée indiquent que la rispéridone a un effet modéré sur le comportement perturbateur et agressif chez les adolescents ayant un QI moyen et un TOP ou un TC, avec et sans TDAH. Les données probantes soutenant l’utilisation d’halopéridol, de thioridazine, de quétiapine, et de lithium chez les adolescents agressifs souffrant de TC sont de qualité faible ou très faible, et les données probantes soutenant l’utilisation de divalproex chez les adolescents agressifs souffrant du TOP ou du TC sont de faible qualité. Des données probantes de qualité très faible indiquent que la carbamazépine n’est pas différente d’un placebo pour la prise en charge de l’agressivité chez les adolescents souffrant du TC.

Conclusion :

À l’exception de la rispéridone, les données probantes soutenant l’utilisation des antipsychotiques et des régulateurs de l’humeur sont de faible qualité.

Aggression is a major predictor of disability and negative psychosocial outcomes in children with ADHD, ODD, and CD. These are among the most common psychiatric diagnoses in childhood, with 4.1% of Canadian school-age children diagnosed with ADHD,1 1% to 6% of children with ODD, and 0.2% to 2% with CD.2 Population-based data from the 1999 British Child Mental Health Survey have shown that, among children diagnosed with ADHD, the rate of comorbid ODD is about 30%, and of CD about 31%.3 Aggression in children with ADHD is a major risk factor for the development of criminality in adolescence and adulthood,4 and negatively influences quality of life for children and their families.5 Therefore, providing effective and safe treatments for aggression and other disruptive behaviour is of extreme importance.

Clinical Implications

There is evidence to support the clinical efficacy of risperidone for the treatment of aggressive behaviour in youth with ODD and CD, with and without ADHD.

Evidence supporting the use of other antipsychotics and mood stabilizers for this purpose is of low quality.

Adverse effects related to risperidone use should be strongly considered prior to prescribing it to children.

Limitations

There are a limited number of studies of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers for the treatment of aggression in youth with ADHD, ODD, and CD.

Four Canadian pharmacoepidemiologic studies conducted during the past 2 years have found a sharp increase in the use of antipsychotics in children. One national study6 and 3 provincial studies in British Columbia,7 Manitoba,8 and Nova Scotia9 consistently demonstrate rising use, with the greatest increases in the use of the risperidone for the treatment of ADHD and CD. Prescribers of these medications for children include psychiatrists, pediatricians, and family physicians, with at least 50% of prescriptions from family physicians. A major concern regarding the use of antipsychotics is their propensity to cause metabolic, hormonal, and extrapyramidal side effects,10 which can have negative long-term health consequences. Metabolic side effects include weight gain, increase in body mass index, and waist circumference, and abnormalities in cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, insulin, and liver enzymes. Hormonal side effects include elevated prolactin and thyroid hormone abnormalities. Extrapyramidal side effects include akathisia, drug-induced parkinsonism, tardive dyskinesia, and tardive dystonia. Therefore, the decision to prescribe antipsychotics for children must be approached very cautiously. Antipsychotics require intensive monitoring for adverse effects,11 which requires an investment of effort and time by both the clinician and the patient. While not commonly used for the management of disruptive behaviour, lithium and anticonvulsants also carry a risk of adverse effects that require safety monitoring.

In Part 1 of this Systematic Review,12 we reviewed the effectiveness and safety of ADHD medications—psychostimulants, alpha-2 agonists, and atomoxetine—for the treatment of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in youth with ADHD, with and without ODD and CD. The purpose of Part 2 is to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of antipsychotics and traditional mood stabilizers for the same indication. We aim to provide the clinician with a synthesis of information on the quality of evidence and effect size for these medications when prescribed for aggressive and disruptive behaviour in this population.

Methods

Please refer to the companion Systematic Review paper,12 Part 1 in this issue, for this information, as the methods followed for this paper are identical. See online eAppendix 1 for electronic search strategies.

Results

Results of the Search

See online eAppendix 2 for flow diagrams. We included 11 RCTs of antipsychotics and 7 RCTs of traditional mood stabilizers.

Study Participants

Most studies included youth with ODD or CD, with and without ADHD. Six studies included people with subaverage IQ with ODD, CD, or DBD-NOS; most subjects in these studies had ADHD as well. All studies included more boys than girls.

Study Outcomes

Several different scales were used to measure conduct problems and aggression in the included studies. These included the Nisonger Child Behaviour Rating Form, the Aberrant Behaviour Checklist, the CGI scale, the Child Aggression Scale, the Rating of Aggression Against People or Property Scale, the Conners Parent–Teacher Questionnaire, and the OAS. Descriptions of each scale can be found in online eAppendix 3.

Treatment Effects

Antipsychotics

Eleven studies of antipsychotics met inclusion criteria; 8 studied risperidone, 1 studied quetiapine, 1 studied haloperidol, and 1 studied thioridazine. See online eAppendix 4 for included study characteristics, quality ratings, results of individual RCTs, including detailed information about adverse effects, and online eAppendix 5 for a list of excluded studies. Owing to variations in adverse effect reporting between studies, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis on adverse effect data. We found 3 additional RCT protocols registered on the clinicaltrials.gov website, for which no results were available. These included 1 RCT of aripiprazole for ADHD, 1 RCT of ziprasidone for CD, and 1 RCT of molindone in youth with impulsive aggression and ADHD.

Risperidone in Youth With Subaverage IQ and ODD, CD, or DBD-NOS

Four studies evaluated the use of risperidone in youth with subaverage IQ and ODD, CD, or DBD-NOS; most children also had comorbid ADHD (59% to 76%).13–16 A fifth study, which evaluated maintenance treatment with risperidone, included both youth with subaverage IQ (36%) and youth with average IQ.17 These 5 studies included a total of 398 children. Trial size ranged from 13 to 119 participants (mean 80, SD 50.3). Trials ranged in length from 4 weeks to 6 months. Most participants were boys. Four studies were rated as class II, and 1 was rated as class I. All studies assessed conduct problems or aggression as their primary outcome. All studies reported a significant benefit with risperidone treatment.

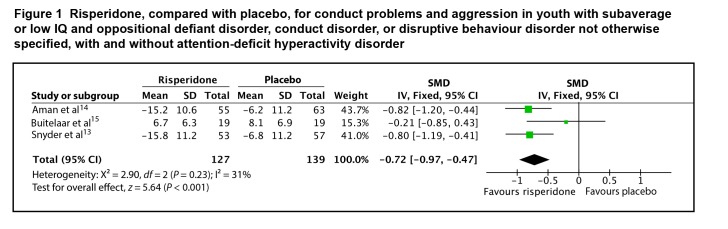

Three of the 5 studies provided data on end point or change scores that could be included in the meta-analysis. The SMD between risperidone and placebo for conduct problems and aggression was 0.72 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.97; I2 = 31%, P < 0.001), by fixed-effects model (Figure 1). The evidence profile for risperidone for youth with subaverage IQ is presented in Table 1. Overall, there is moderate-quality evidence that risperidone has a moderate-to-large effect on conduct problems and aggression in youth with subaverage IQ, ODD, CD, or DBD-NOS, with and without ADHD.

Figure 1.

Risperidone, compared with placebo, for conduct problems and aggression in youth with subaverage or low IQ and oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, or disruptive behaviour disorder not otherwise specified, with and without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Table 1.

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation evidence profiles for antipsychotics

| Outcome assessed; number of studies; number of patients; study duration | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Dose–response effect present? | Summary of findings | Overall quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risperidone for conduct problems and aggression in youth with subaverage IQ and ODD or CD, with and without ADHD | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Conduct problems and aggression | Minor limitations in study quality | No serious inconsistency | No indirectness | No serious imprecision | Possible publication bias | No evidence of dose–response effect for this outcome | SMD, risperidone, compared with placebo: 0.72 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.97) | Moderatea |

| 5 RCTs; | ||||||||

| 398 patients; | ||||||||

| 4 weeks to 6 months | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Risperidone for disruptive and aggressive behaviour in youth with ODD and CD, with and without ADHD | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

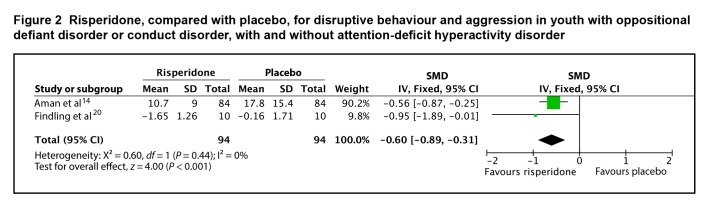

| Disruptive and aggressive behaviour | No limitations in study quality | No serious inconsistency | No indirectness | No serious imprecision | Possible publication bias | No evidence of dose–response effect for this outcome | SMD, risperidone, compared with placebo: 0.60 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.89) | High |

| 4 RCTs; | ||||||||

| 429 patients; | ||||||||

| 4 weeks to 6 months | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Quetiapine for conduct problems in youth with CD, with and without ADHD | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Conduct problems | Major limitations in study quality | Unable to assess | No indirectness | Some imprecision | Possible publication bias | No evidence of dose–response effect for this outcome | Clinical Global Impression—Severity, quetiapine, compared with placebo, effect size 1.6 (95% CI 0.9 to 3.0) | Very lowa |

| One RCT; | ||||||||

| 19 patients; | ||||||||

| 6 weeks | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Haloperidol for aggression in youth with CD | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Aggression | Major limitations in study quality | Unable to assess | No indirectness | Unable to assess | Possible publication bias | No evidence of dose–response effect for this outcome | Haloperidol was significantly different from placebo on measures of hostility and aggression (magnitude of effect not reported). | Very lowa |

| One RCT; | ||||||||

| 61 patients; | ||||||||

| 4 weeks | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Thioridazine for conduct problems in youth with subaverage IQ and ADHD or CD | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Conduct problems | Major limitations in study quality | Unable to assess | No indirectness | Unable to assess | Possible publication bias | No evidence of dose–response effect for this outcome | Unable to calculate effect size for data; small difference between thioridazine and placebo on the Conduct Problems subscale of the Conners Teacher Questionnaire | Very lowa |

| One RCT; | ||||||||

| 30 patients; | ||||||||

| 3 weeks | ||||||||

Overall quality was downgraded based on limitations in study quality.

Risperidone in Youth With Average IQ and ODD or CD, With and Without ADHD

Four RCTs have evaluated risperidone in aggressive youth with average IQ: 2 used risperidone for treatment-resistant aggression in the context of ADHD (comorbid ODD–CD in 97%)18,19; 1 used risperidone for the treatment of aggression in CD (without moderate or severe ADHD)20; and 1 was the previously mentioned maintenance study that included youth with average IQ (64%) and subaverage IQ who had ODD, CD, or DBD-NOS (ADHD in 68%).17 These 4 studies included a total of 429 participants, with a trial size ranging from 25 to 216 participants (mean 107, SD 99.8). Trials ranged in length from 4 weeks to 6 months. Methodological quality was rated as class I for 2 studies and class II for 2 studies. All studies assessed disruptive or aggressive behaviour as their primary outcome.

Two of the 4 studies provided end point or change data that could be included in the meta-analysis. The SMD between risperidone and placebo for disruptive behaviour and aggression was 0.60 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.89; I2 = 0%, P < 0.001), by fixed-effects model (Figure 2). The evidence profile for risperidone for youth with average IQ is presented in Table 1. Overall, there is high-quality evidence that risperidone has a moderate effect on disruptive and aggressive behaviour in youth with average IQ and ODD or CD, with and without ADHD.

Figure 2.

Risperidone, compared with placebo, for disruptive behaviour and aggression in youth with oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder, with and without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Quetiapine in Youth With CD

There is one class III–quality study evaluating the use of quetiapine in youth with CD. Connor et al21 evaluated 19 adolescents with moderate-to-severe aggressive behaviour in a 7-week RCT. A comorbid diagnosis of ADHD was present in 79%, although treatment with ADHD medication (or any other psychotropic) was not permitted. Clinician-ascertained CGI-S and CGI—Improvement scale scores were the primary outcomes of the study. CGI-S scores decreased from 5.9 at randomization to 3.4 at end point with quetiapine, compared with a decrease from 5.5 to 5.0 with placebo (P = 0.007). Based on regression results from mixed-effects models, CGI-S scores in the quetiapine group were estimated to decline by 1.80 units, thus −1.80 (95% CI −0.53 to −3.10), more than in the placebo group, corresponding to an effect size of 1.6 (95% CI 0.9 to 3.0). Changes in secondary outcomes, including the OAS and the Conners Parent Rating Scale, were not significantly different between groups.

The evidence profile for quetiapine is presented in Table 1. Based on the one placebo-controlled study, there is very low-quality evidence that quetiapine has a large effect on conduct problems in youth with CD. As the evidence for quetiapine is limited to one small study using a nonspecific rating instrument to evaluate conduct problems, confidence in the estimate of the effect is extremely low.

Haloperidol in Youth With CD

There is one class III–quality study evaluating the use of haloperidol in aggressive youth with CD. Campbell et al22 randomized 61 hospitalized youth to 4 weeks of treatment with haloperidol, lithium carbonate, or placebo. A primary outcome was not specified; numerous behavioural measures were used, including the Children’s Psychiatric Rating Scale, the CGI, the Conners Teacher Questionnaire, and the Conners Parent–Teacher Questionnaire. Change scores or scores at end point on these measures were not provided in the article. The authors stated that haloperidol did not differ from lithium, but the 2 drugs did differ from placebo for the hyperactivity, hostility, and aggression clusters of the Children’s Psychiatric Rating Scale. On the CGI, children in all 3 groups were initially rated as severely ill. At 4 weeks, children in the haloperidol and lithium groups were rated as mildly ill, whereas the placebo group was rated as a little worse than markedly ill. Haloperidol did not differ from lithium on this outcome, but the 2 drugs did differ from placebo (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference between either of the 2 drugs and the placebo on the Conners Teacher Questionnaire or the Conners Parent– Teacher Questionnaire.

The evidence profile for haloperidol is presented in Table 1. There is very-low-quality evidence that haloperidol has an effect on aggressive behaviour in youth with CD. The evidence for haloperidol is limited to one study, and as no change scores or scores at end point for behavioural measures are provided, the magnitude of the effect of haloperidol is uncertain.

Thioridazine in Youth With Subaverage IQ and ADHD or CD

There is one class III–quality study evaluating the use of thioridazine in youth with subaverage IQ and ADHD or CD. Aman et al23 performed a crossover study in 30 children of 3 weeks of treatment with thioridazine, methylphenidate, and placebo. A primary outcome was not specified; behavioural measures included the Conners Teacher Questionnaire, the Conners Abbreviated Teacher Rating Scale, and the Revised Behaviour Problem Checklist. On the Conners Teacher Questionnaire, methylphenidate and thioridazine were superior to placebo on the Conduct Problems subscale. Standard deviations, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals were not provided for any of the data, preventing the calculation of an effect size. There was no significant difference between either of the 2 drugs and the placebo on any of the parent ratings of behaviour.

The evidence profile for thioridazine is presented in Table 1. There is very-low-quality evidence that thioridazine has a small effect on conduct problems in youth with subaverage IQ and ADHD or CD. The evidence for thioridazine is limited to one study of poor quality; confidence in the estimate of the effect is very low.

Mood Stabilizers

Seven studies met our inclusion criteria: 4 studies of lithium, 2 studies of divalproex, and 1 study of carbamazepine. See online eAppendix 4 for study characteristics, quality ratings, results of individual RCTs, including detailed information about adverse effects, and online eAppendix 5 for a list of excluded studies. Owing to variations in adverse effect reporting between studies, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis on adverse effect data.

Lithium in Youth With CD

There are 4 studies comparing lithium with placebo for the treatment of aggression in hospitalized youth with CD, including a total of 184 children. Most participants were boys. Trials ranged in length from 2 to 6 weeks. Methodological quality was rated as class I for 1 study, class II for 1 study, and class III in 2 studies. One study24 in adolescents with CD reported no difference between lithium and placebo on any behavioural measures, whereas another study25 in children and adolescents with CD reported a significant difference between lithium and placebo on all behavioural measures. The remaining 2 studies22,26 did not specify a primary outcome, and reported a mix of significant and nonsignificant results on multiple behavioural outcomes.

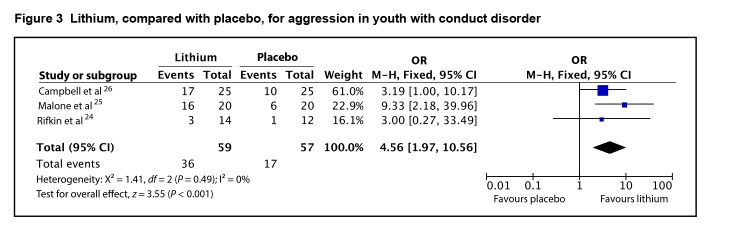

Three of the 4 studies provided data that could be incorporated into a meta-analysis using the dichotomous outcomes of responder or remission status. Treatment with lithium was associated with a higher odds of response or remission than placebo, with an odds ratio of 4.56 (95% CI 1.97 to 10.56; I2 = 0%, P < 0.001) by fixed-effects model (Figure 3). The evidence profile for lithium is presented in Table 2. Overall, there is low-quality evidence that lithium is associated with a higher odds of response or remission than placebo for aggressive behaviour in hospitalized youth with CD. The evidence for lithium is inconsistent, and there are limitations in study quality, making confidence in the amount of benefit low.

Figure 3.

Lithium, compared with placebo, for aggression in youth with conduct disorder

Table 2.

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation evidence profiles for traditional mood stabilizers

| Outcome assessed; number of studies; number of patients; study duration | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Dose–response effect present? | Summary of findings | Overall quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valproic acid for aggression in youth with ODD and CD, with and without ADHD | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

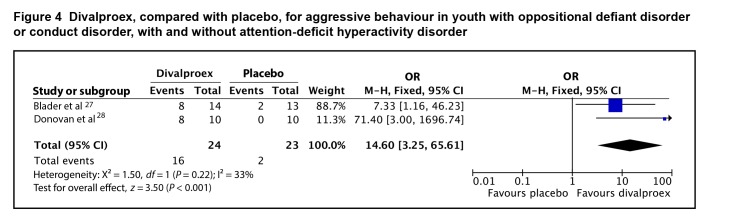

| Aggression | Some limitations in study quality | No inconsistency | No indirectness | Imprecision of results | Possible publication bias | No evidence of dose–response effect for this outcome | OR for responder in aggressive behaviour (40% to 70% improvement in symptoms), valproic acid, compared with placebo, 14.6 (95% CI 3.25 to 65.61) | Lowa |

| 2 RCTs; | ||||||||

| 50 patients; | ||||||||

| 6 to 8 weeks | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Carbamazepine for aggression in youth with CD | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Aggression | Major limitations in study quality | Unable to assess | No indirectness | Unable to assess | Possible publication bias | No evidence of dose–response effect for this outcome | No difference between carbamazepine and placebo on the Overt Aggression Scale | Very lowb |

| One RCT; | ||||||||

| 24 patients; | ||||||||

| 6 weeks | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Lithium for aggression in youth with CD | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Aggression | Some limitations in study quality | Some inconsistency | No indirectness | Some imprecision of results | Possible publication bias | No evidence of dose–response effect for this outcome | OR for responder or remission status, lithium, compared with placebo, 4.56 (95% CI 1.97 to 10.56) | Lowc |

| 4 RCTs; | ||||||||

| 184 patients; | ||||||||

| 2 to 6 weeks | ||||||||

Overall quality was downgrade based on study quality and large degree of imprecision in results.

Overall quality was downgrade based on study quality.

Overall quality was downgrade based on study quality and inconsistency in results.

Divalproex in Youth With ODD and CD, With and Without ADHD

There are 2 studies evaluating the use of divalproex in youth with ODD or CD. One trial added divalproex to open stimulant treatment in youth with ADHD and ODD or CD for the treatment of aggression27; the other evaluated divalproex for the treatment of aggression in youth with ODD or CD (ADHD comorbid in 20%).28 The 2 trials included a total of 50 youth, with treatment lasting 6 to 8 weeks. Most participants were boys. Methodological quality was rated as class II for both studies. Both studies dichotomized patients as responders or nonresponders to treatment based on the extent of symptom reduction or reaching a threshold score on the outcome measure at end point. Both trials reported a significantly higher odds of responder status with divalproex, compared with placebo.

Both studies were incorporated into a meta-analysis using the data provided on responder status. Treatment with divalproex was associated with a higher odds of responder status than placebo, with an odds ratio of 14.60 (95% CI 3.25 to 65.61; I2 = 33%, P < 0.001), by fixed-effect model (Figure 4). The evidence profile for divalproex is presented in Table 2. Overall, there is low-quality evidence that divalproex is associated with a higher odds of response for aggressive behaviour in youth with ODD or CD, with and without ADHD, compared with placebo. The wide confidence interval indicates that the evidence for divalproex is imprecise, making confidence in the amount of benefit low.

Figure 4.

Divalproex, compared with placebo, for aggressive behaviour in youth with oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder, with and without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Carbamazepine in Youth With CD

There is one poor-quality study of carbamazepine in aggressive youth with CD. Cueva et al29 performed a 6-week study of 24 youth with carbamazepine, compared with placebo. A primary outcome was not specified; the OAS was the main measure of aggressiveness. There was no difference between carbamazepine and placebo on any of the outcome measures of the study.

The evidence profile for carbamazepine is presented in Table 2. There is very-low-quality evidence that carbamazepine is no different than placebo for the management of aggression in youth with CD.

Discussion

Summary of Main Results

There is moderate-quality evidence that risperidone has a moderate–to-large effect on conduct problems and aggression in youth with subaverage IQ and ODD, CD, or DBD-NOS, with and without ADHD.

There is high-quality evidence that risperidone has a moderate effect on disruptive and aggressive behaviour in youth with average IQ and ODD or CD, with and without ADHD.

There is very-low-quality evidence that quetiapine has a large effect on conduct problems in youth with CD.

There is very-low-quality evidence that haloperidol has an effect (magnitude uncertain) on aggressive behaviour in youth with CD.

There is very-low-quality evidence that thioridazine has a small effect on conduct problems in youth with subaverage IQ and ADHD or CD.

There is low-quality evidence that lithium is associated with a higher odds of response or remission than placebo for aggressive behaviour in youth with CD.

There is low-quality evidence that divalproex is associated with a higher odds of response or remission, compared with placebo, for aggressive behaviour in youth with ODD or CD, with and without ADHD.

There is very-low-quality evidence that carbamazepine is no different from placebo for the management of aggression in youth with CD.

Overall Completeness and Applicability of Evidence

In studies evaluating risperidone for the treatment of aggression in youth with average IQ, 425 of 429 included subjects had comorbid ODD or CD, suggesting that this evidence should only be applied to youth who have these comorbid diagnoses, rather than to those with ADHD only. Indeed, it is unlikely that a child with ADHD who did not qualify for a comorbid ODD or CD diagnosis would have severe enough symptoms of aggression to justify risperidone treatment. Similarly, all participants in studies of quetiapine, haloperidol, divalproex, carbamazepine, and lithium had ODD or CD. Studies of lithium were performed exclusively in hospitalized patients with CD, suggesting that applicability may be limited to youth in this setting. Further, given the close drug safety monitoring required with lithium, it is likely that only in an inpatient setting could youth with CD comply with the demands of treatment, at least until their symptoms are under better control.

Most studies included children with ODD, or CD, with and without ADHD. None of the trials subanalyzed results based on ADHD comorbidity; rather, they presented aggregate data for all included subjects. As such, it is not possible to determine differences in treatment response based on the presence and absence of ADHD. For all medications, studies were of short duration, typically lasting weeks; only 1 study of risperidone evaluated treatment for 6 months. Therefore, the clinician is faced with the difficulty of deciding how long to continue a successful treatment once started.

The overall quality of evidence was low or very low for all medications but risperidone. With low- and very-low-quality evidence, any estimate of effect is very uncertain, and further research is very likely to have an important impact on the estimate as well as on our confidence in it. Therefore, the estimates of effect size and results of individual studies for these medications should be interpreted with caution. Publication bias is also a concern for most of the medications studied, as there are few published studies.

Conclusions

Implications for Practice

While there is evidence to support the efficacy of risperidone for the treatment of disruptive and aggressive behaviour in youth with ADHD, ODD, and CD, this evidence must be weighed against potential adverse effects and considered in light of evidence supporting the use of psychosocial therapies. In the T-MAY guidelines developed through the CERT, the authors performed a systematic review of psychosocial interventions for aggression in youth.30 The most-studied interventions for children 8 years of age and younger were found to be group parent training treatment programs, with an effect size of 0.50 to 0.83, and multicomponent treatment approaches (involving a combination of positive parenting, interpersonal and social skills for children, and classroom management for teachers), with an effect size of 0.23 to 0.38.30 Psychosocial interventions for children older than 8 years included 3 different approaches. Brief strategic family therapy to modify family interactions had an effect size of 0.68; multisystemic therapy to increase family communication, parenting skills, and peer relationships had an effect size of 0.25; and cognitive-behavioural therapy had an effect size of 0.58 and demonstrated sustained reduction in anger episodes several months after the intervention.30

Based on the above evidence, the CERT T-MAY guidelines make strong recommendations for psychoeducation and the provision of age-appropriate, evidence-based parent and child skills training during all phases of care. As the effect sizes demonstrated for these psychosocial therapies are in the same range as the effect sizes of most medications assessed in our systematic review, clinicians should be encouraged to recommend psychosocial therapy as initial management of disruptive and aggressive behaviour in children with ADHD, ODD, or CD. Financial, systemic, and cultural barriers to the implementation of psychosocial interventions have likely contributed significantly to the increasing use of medication for these problems. In many communities, psychosocial therapies are difficult to access, especially in urgent or crisis situations. In addition, psychosocial therapies require an investment of time and effort on the part both of parents and of youth, who may therefore be unwilling or unable to engage in these treatments.

Implications for Research

Recommendations for further research include head-to-head trials comparing different medications for the management of disruptive and aggressive behaviour, and trials comparing medications with psychosocial therapies. Longer-duration studies to evaluate both safety and long-term efficacy are also needed, in addition to placebo discontinuation studies to guide clinicians on when medications for disruptive and aggressive behaviour should be discontinued.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support for individual studies included in the systematic review can be found in online eAppendix 4, Table of Included Studies. Funding support for the systematic review came from the Royal Bank of Canada Knowledge Translation Fund and the SickKids Foundation.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

- CD

conduct disorder

- CERT

Center for Education and Research on Mental Health Therapeutics

- CGI

Clinical Global Impression

- CGI-S

CGI—Severity

- DBD-NOS

disruptive behaviour disorder not otherwise specified

- OAS

Overt Aggression Scale

- ODD

oppositional defiant disorder

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SMD

standardized mean difference

- T-MAY

Treatment of Maladaptive Aggression in Youth

Footnotes

Editor’s Note

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of either The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry (The CJP) or the Canadian Psychiatric Association (CPA). This paper is not related to work done by the CPA’s Committee on Professional Standards and Practice or its Subcommittee on Clinical Practice Guidelines, and its publication in The CJP should not be construed as an endorsement of the content.

References

- 1.Brault MC, Lacourse E. Prevalence of prescribed attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medications and diagnosis among Canadian preschoolers and school-age children: 1994–2007. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(2):93–101. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breton JJ, Bergeron L, Valla JP, et al. Quebec Child Mental Health Survey: prevalence of DSM-III-R mental health disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(3):375–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maughan B, Rowe R, Messer J, et al. Conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder in a national sample: developmental epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(3):609–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pingault JB, Côté SM, Lacourse E, et al. Childhood hyperactivity, physical aggression and criminality: a 19-year prospective population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e62594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klassen AF, Miller A, Fine S. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents who have a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e541. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pringsheim T, Lam D, Patten S. The pharmacoepidemiology of antipsychotic medications for Canadian children and adolescents: 2005–2009. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(6):537–543. doi: 10.1089/cap.2010.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ronsley R, Scott D, Warburton WP, et al. A population-based study of antipsychotic prescription trends in children and adolescents in British Columbia, from 1996 to 2011. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(6):361–369. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alessi-Severini S, Biscontri RG, Collins DM, et al. Ten years of antipsychotic prescribing to children: a Canadian population-based study. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(1):52–58. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy AL, Gardner DM, Cooke C, et al. Prescribing trends of antipsychotics in youth receiving income assistance: results from a retrospective population database study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):198. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pringsheim T, Lam D, Ching H, et al. Metabolic and neurological complications of second-generation antipsychotic use in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug Saf. 2011;34(8):651–668. doi: 10.2165/11592020-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pringsheim T, Panagiotopoulos C, Davidson J, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for monitoring safety of second-generation antipsychotics in children and youth. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16(9):581–589. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pringsheim T, Hirsch L, Gardner DM, et al. The pharmacological management of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 1: psychostimulants, alpha-2 agonists, and atomoxetine. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(2):42–51. doi: 10.1177/070674371506000202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snyder R, Turgay A, Aman M, et al. Effects of risperidone on conduct and disruptive behavior disorders in children with subaverage IQs. Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(9):1026–1036. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aman M, De Smedt G, Derivan A, et al. Risperidone Disruptive Behavior Study Group Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone for the treatment of disruptive behaviors in children with subaverage intelligence. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(8):1337–1346. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buitelaar J, van der Gaag R, Cohen-Kettenis P, et al. A randomized controlled trial of risperidone in the treatment of aggression in hospitalized adolescents with subaverage cognitive abilities. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(4):239–248. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Bellinghen M, De Troch C. Risperidone in the treatment of behavioral disturbances in children and adolescents with borderline intellectual functioning: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001;11(1):5–13. doi: 10.1089/104454601750143348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reyes M, Buitelaar J, Toren P, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone maintenance treatment in children and adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):402–410. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aman M, Bukstein OG, Gadow KD, et al. What does risperidone add to stimulant and parent training for severe aggression in child attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armenteros JL, Lewis JE, Davalos M. Risperidone augmentation for treatment-resistant aggression in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(5):558–565. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180323354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Findling RL, McNamara NK, Branicky LA, et al. A double-blind pilot study of risperidone in the treatment of conduct disorder. Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(4):509–516. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connor DF, McLaughlin TJ, Jeffers-Terry M. Randomized controlled pilot study of quetiapine in the treatment of adolescent conduct disorder. J Child Adolescent Psychopharmacol. 2008;18(2):140–156. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell M, Small AM, Green WH, et al. Behavioral efficacy of haloperidol and lithium carbonate. A comparison in hospitalized aggressive children with conduct disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41(7):650–656. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790180020002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aman MG, Marks RE, Turbott SH, et al. Methylphenidate and thioridazine in the treatment of intellectually subaverage children: effects on cognitive-motor performance. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30(5):816–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rifkin A, Karajgi B, Dicker R, et al. Lithium treatment of conduct disorders in adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(4):554–555. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malone RP, Delaney MA, Luebbert JF, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lithium in hospitalized aggressive children and adolescents with conduct disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(7):649–654. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell M, Adams PB, Small AM, et al. Lithium in hospitalized aggressive children with conduct disorder: a double-blind and placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(4):445–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blader JC, Schooler NR, Jensen PS, et al. Adjunctive divalproex versus placebo for children with ADHD and aggression refractory to stimulant monotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(12):1392–1401. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donovan SJ, Stewart JW, Nunes EV, et al. Divalproex treatment for youth with explosive temper and mood lability: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover design. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):818–820. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.818. Erratum in: Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cueva JE, Overall JE, Small AM, et al. Carbamazepine in aggressive children with conduct disorder: a double-blind and placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(4):480–490. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199604000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scotto Rosato N, Correll CU, Pappadopulos E, et al. Treatment of maladaptive aggression in youth: CERT guidelines II. Treatments and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):e1577–e1586. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.