Abstract

Background: The use of emergency department (ED) services for non-urgent conditions is well-studied in many Western countries but much less so in the Middle East and Gulf region. While the consequences are universal—a drain on ED resources and poor patient outcomes—the causes and solutions are likely to be region and country specific. Unique social and economic circumstances also create gender-specific motivations for patient attendance. Alleviating demand on ED services requires understanding these circumstances, as past studies have shown. We undertook this study to understand why female patients with low-acuity conditions choose the emergency department in Qatar over other healthcare options. Setting and design: Prospective study at Hamad General Hospital's (HGH) emergency department female “see-and-treat” unit that treats low-acuity cases. One hundred female patients were purposively recruited to participate in the study. Three trained physicians conducted semi-structured interviews with patients over a three-month period after they had been treated and given informed consent. Results: The study found that motivations for ED attendance were systematically influenced by employment status as an expatriate worker. Forty percent of the sample had been directed to the ED by their employers, and the vast majority (89%) of this group cited employer preference as the primary reason for choosing the ED. The interviews revealed that a major obstacle to workers using alternative facilities was the lack of a government-issued health card, which is available to all citizens and residents at a nominal rate. Conclusion: Reducing the number of low-acuity cases in the emergency department at HGH will require interventions aimed at encouraging patients with non-urgent conditions to use alternative healthcare facilities. Potential interventions include policy changes that require employers to either provide workers with a health card or compel employees to acquire one for themselves.

Keywords: emergency medicine, emergency department overcrowding, female patients, policy implications

Introduction

Increasing demand for emergency department (ED) services is a worldwide phenomenon that has been well-studied in many Western and developed countries, such as the United Kingdom and United States.1–5 Much less is known about ED utilization in the Middle East and North Africa, areas of the world that have diverse populations with unique socio-cultural values that likely contribute to different patterns in patient attendance and use. Such is the case in Qatar, a country that has experienced a 15-fold increase in population size over the past few decades, rising from 111,000 in 1970 to 1.7 million in 2011—1.4 million (85%) of whom are foreign workers with diverse national backgrounds.6

The influx of migrant workers has tipped the age structure so that 82.6 percent of the population is between the working ages of 15-64 and created an imbalanced gender ratio of 308 (i.e., 308 males for every 100 females) because the vast majority of foreign workers are male.7 Most are single or have spouses in their home countries, and thus lack familial and social environments that are known to be conducive to healthier lifestyles.8 There is also a large and growing number of low-income female expatriate laborers who work as household servants or in service industries and lack the resources needed to access care.

This growth has put increasing strain on ED services, with daily attendance at Hamad General Hospital's (HGH) tertiary emergency department averaging 1,300 patients a day or 33,000 a month in a city with less than two million residents.9 While some patients arrive with urgent medical needs, a large proportion present with low-acuity complaints that might be better treated in community based facilities. In 2012, for example, the ED at Hamad General Hospital treated a total of 423,389 patients, only ten percent of whom arrived by Emergency Medical Services (EMS). This stands in contrast to statistics in the United Kingdom where 25 percent of ED patients in 2012 arrived by EMS.10 Moreover, 80% of all male patients and 92% of all female patients in the ED were classified as “See and Treat,” (SnT) which are generally low-acuity cases. The vast majority of both male and female SnT patients were discharged rather than admitted to the hospital (84% and 75%, respectively).7

The presence of low-acuity patients can divert attention away from more seriously ill patients and adversely impact the timely provision of services to those in urgent need.11,12 ED overcrowding and attendance by low-acuity patients is not a phenomenon unique to Qatar, alone.3,13,14 However, the factors that drive ED attendance for low-acuity conditions vary considerably geographically due to differences in the social, cultural and economic circumstances that shape patient choices when seeking healthcare. For example, in low-income countries, the ED is often the only option for care because of a general lack of healthcare infrastructure. In more developed countries, the ED can operate as a safety net for patients who cannot afford care at other facilities.4 In other countries still, patient motivations for ED attendance may be driven less by economic factors than by cultural differences in defining what constitutes a health emergency, and thus where one chooses to seek treatment.15

The healthcare system in Qatar may also create different motivations for ED attendance. The system is overseen by the Supreme Council of Health, a government institution tasked with ensuring the quality and delivery of health services at private and public facilities. Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) is the largest public entity in Qatar, with five hospitals and twenty-four community clinics. Healthcare services can be accessed by all citizens and residents at a heavily subsidized rate at HMC clinics and hospitals through the use of a government-issued health card which is available for a nominal annual fee of 100 Qatari Riyals, equivalent to $28 US Dollars per year.16 However, access to these services varies by nationality and gender, with Qatari citizens having the greatest access and migrant workers having the least access due to the lack of a health card. Male migrant men are further disadvantaged because of restrictions on which clinics they can use. Specifically, male migrant bachelors can only access emergency departments at HMC hospitals or two Red Crescent Worker's Health Clinics. In contrast, female migrant workers can access multiple health clinics in and around Doha and receive free consultations (similar to HMC-ED) provided they have a health card.

This is the first empirical study aimed at understanding the use of emergency department services for low-acuity conditions in Qatar. We expand on previous studies in the region to include nationals and non-nationals,14 which is an important contribution given the size of the expatriate population and potential differences in their motivations for ED attendance. We focus on female patients for several reasons. First, health complaints and health-seeking behaviors are known to vary for men and women.8 For example, men are more likely to present with work-related injuries and wounds,17 while women are more likely to present with conditions such as arthritis or upper respiratory tract infection.9 Second, as described above, women in Qatar have access to a larger network of non-emergency healthcare facilities than men, and this is particularly true for migrant workers.18 Thus identifying why females seek care for non-urgent conditions in the emergency department will potentially allow for interventions that direct them to more appropriate facilities and free ED resources for use on more critical cases.

Study Design

Setting

The ED at HGH is a tertiary level healthcare facility that provides free healthcare to anyone who lives in Qatar. In 2012, it served over 400,000 patients (71% male, 29% female). The vast majority presented with low-acuity conditions (80%) that were treated in separate male and female treatment areas. Low-acuity ambulant patients were seen in see and treat areas, non ambulatory patients in urgent areas and high acuity patients in mixed gender resuscitation bays. Of the low acuity cases, 81% were discharged and 19% admitted.7

Sample

The research team used data from 2012 ED files to generate descriptive statistics on patterns in ED attendance among non-urgent female see-and-treat patients. The data showed that 92% of all female ED patients (n = 121,115) were classified with low-acuity conditions, 71% were non-Qatari, and 87% were under the age of 54. We used these statistics to purposively recruit a random sample of 100 female patients to represent the overall population in terms of these characteristics. We excluded certain low-acuity conditions, such as minor trauma and lacerations, which are best treated in the ED and focused on those that can be treated in alternative health centers, such as upper respiratory tract infections. Patients in physical or psychological distress were also excluded.

Methods

The research team created an interview schedule based on prior studies in the region that focused on reasons for non-urgent ED attendance.14 We also held three focus groups with low-acuity female patients, ED nurses, and ED doctors to help develop the interview schedule within the context of Qatar. The focus groups provided the language used by patients and staff when discussing motivations for low-acuity attendance and also provided probes that were included on the instrument (Appendix A). The interview schedule was then piloted with five low-acuity female patients, and slight alterations were made to the wording and ordering of the questions based on the pre-test. Three physicians trained in the process of data collection conducted semi-structured interviews with patients over a three-month period after the patients had been treated for their condition and given informed consent (HMC ethics protocol #14075). The interviews were conducted during operational hours of other healthcare facilities to reduce the likelihood that patient attendance was driven by the need for after hour services. This was done intentionally because the primary goal of the study was to assess patient motivations for attendance when other facilities were available (i.e., the ED is their only choice after hours). The interviews lasted 10-15 minutes and focused on the patient's prior experiences with health services in Qatar, knowledge of alternative health facilities, access to facilities, and factors shaping their decision-making process to attend the ED.

Analyses

The research team created an Excel database using de-identified responses from the 100 cases. We first organized the open-ended responses into categories and then assigned each category a code for analyses. For example, we identified five categories of responses to question #4 on Appendix A (reasons for choosing the ED over other facilities): 1) better/faster care; 2) ease of accessibility; 3) lack of knowledge of other facilities; 4) lack of health card/cost; 5) and employer preference. We used these codes to determine whether and how patterns in ED attendance varied across demographic subgroups, as we describe in the Results section below.

Results

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the sample, and Figures 1 and 2 present key findings for patient motivations in ED attendance. Table 1 shows that 25% of the 100 cases were Qatari and 75% were expatriates, numbers that mirror the pattern in female ED attendance in 2012.9 The sample was equally divided in terms of marital status (48% married, 52% single) and was comprised mainly of younger women (58% under the age of 35 with a mean age of 33). Again these figures are similar to those for female SnT patients at HGH in 2012. The primary complaint was upper respiratory tract infection (61%), followed by back pain (23%), toothache (5%), abdominal pain (5%), and other low acuity conditions (6%).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for female see and treat patients at HGH (n = 100).

| Nationality | |

|

| |

| Qatari | 25% |

|

| |

| Non-Qatari | 75% |

|

| |

| Marital status | |

|

| |

| Married | 48% |

|

| |

| Single | 52% |

|

| |

| Primary complaint | |

|

| |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 61% |

|

| |

| Back pain | 23% |

|

| |

| Toothache | 5% |

|

| |

| Abdominal pain | 5% |

|

| |

| Other pain | 6% |

|

| |

| Who made the decision to come to the ED today? | |

|

| |

| Employer | 40% |

|

| |

| Family/self | 60% |

|

| |

| Is this your first visit to the ED at HGH? | |

|

| |

| Responses for those directed by employer (n = 40) | |

|

| |

| Yes | 55% |

|

| |

| No | 45% |

|

| |

| Responses for those directed by family/self (n = 60) | |

|

| |

| Yes | 17% |

|

| |

| No | 83% |

|

| |

| Health card among those employer directed | |

|

| |

| Has a health card | 25% |

|

| |

| Does not have a health card | 75% |

|

| |

| Age in years | |

|

| |

| 18-34 | 58% |

|

| |

| 35-54 | 36% |

|

| |

| 55 and older | 6% |

|

| |

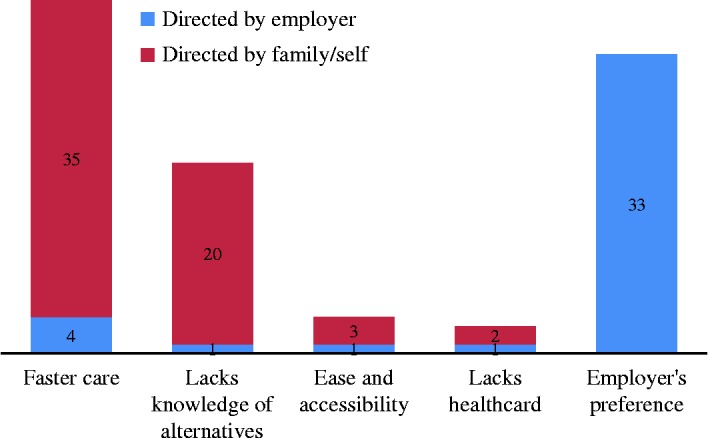

Figure 1.

Primary reasons given for choosing ED by employer direction (n = 100).

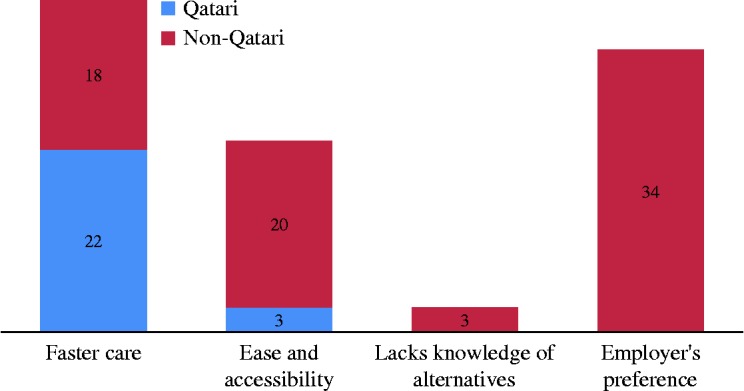

Figure 2.

Primary reasons given for choosing ED by nationality (n = 100).

As seen in Table 1, a key reason patients chose care in the ED was due to employer direction. Of the 100 cases, a plurality (40%) said they were sent by their employers, 35% were brought in by their families, and 25% made the decision to seek care for themselves. The first group was comprised entirely of expatriate workers, with the local Qatari population falling into one of the latter two groups. Notably, those who were sent by their employers all came from industries (e.g., hotels, salons) rather than households (e.g., maids, nannies). Nearly one half (45%) of this group had been to the ED on more than one occasion; they were not single encounters. Most importantly, 75% did not have a health card which limits their ability to access alternative facilities.

1 illustrates important differences in reasons for ED attendance when comparing employer-directed patients to those directed by family/self. Among those sent by their employer, 83% (33 of 40) reported that the primary reason they chose the ED over other facilities was due to employer direction. In contrast, other females in the study cited faster care, accessibility, and/or lack of knowledge of alternative options (58 of 60). This difference maps onto national-origin differences, as seen in Figure 2 which compares Qatari patients to non-Qatari ones. Here we see that the local population primarily cites faster care and accessibility (38 of 40, 98%), while the majority of non-nationals point to employer preference (34 of 60, 57%). This is an important finding because the reasons cited by Qataris mirrors those found when studying nationals in other Western and Gulf countries, such as the United States22 and Saudi Arabia.14 The fact that non-nationals cite alternate reasons indicates the need for more studies that differentiate patient motivations by national origin, particularly in countries with large migrant populations. Although lacking a health card was not frequently listed as a primary problem, the interviews revealed that this was due to it being subsumed by employer preference. Specifically, when we probed the expatriate workers to explain why their employers directed them to the ED, many reported that they did not have a health card and thus their employers sent them to the ED for free services.

Discussion

In countries with diverse populations such as Qatar, motivations for patient attendance can interact in ways that put immense strain on hospital resources and make it difficult to optimally meet the needs of patients. Past studies demonstrate that alleviating emergency department demand requires knowledge of patient motivations for attendance.7,15 These motivations can vary across national contexts due to differences in the economic, social, and cultural environment. Moreover, the uniqueness of the health care systems across countries prevents the extrapolation of findings from prior studies because patient health-seeking behaviors are shaped by these systems. As such, improving patient care and reducing emergency department workload necessitates an understanding of the local context.

Accordingly, we sought to understand factors that drive non-urgent emergency department use among females in Qatar, and the findings were informative. Specifically, we found that motivation for attendance was systematically influenced by employment status, which is different from other developed and developing nations. Studies conducted in the United States, Western Europe, and Australia typically highlight factors such as patient preference, convenience, and lack of health insurance as primary factors motivating ED attendance.20–22 Studies in the Gulf region highlight similar factors, but like those in the West, have focused almost exclusively on citizens and nationals, excluding migrant workers.14,23 As such, none have identified employer direction as a potential mechanism leading to ED attendance. For example, a large cross-sectional study of 28 US hospitals found five factors characterizing patients' reasons for seeking care in the ED: medical necessity, ED preference, convenience, affordability, and limitations of insurance.20 The study concluded that use of ED services was often the patient's choice, a choice driven by lack of access or dissatisfaction with other sources of care. Similarly, a study in Australia found that the main reasons patients sought care for low-acuity conditions in the ED were the perception that their conditions required immediate attention and convenience.21 In a systematic review in the US, a study concluded that non-urgent attendance was largely driven by convenience and negative perceptions of alternative care but again did not differentiate motivations by national origin or citizenship.22

The fact that employers drive many of the females' decisions to attend the ED is unique to Qatar and offers an opportunity for intervention. Specifically, employers should work to help their workers access alternative facilities rather than direct them to the ED. These alternative facilities are available at similar costs to the ED, provided the workers have a health card (cost of 100QR or $28 USD). Unfortunately, many of the workers in our study did not have a health card. Current labor laws in Qatar mandate that employers protect workers against hazardous occupational health and work-related injuries, but they do not require them to provide health insurance nor do they incentivize employers to direct their employees to appropriate community facilities for low acuity health conditions. Health cards would open the door to alternative health facilities that are currently inaccessible due to high out-of-pocket costs. As such, the emergency department often becomes the only viable option for low-paid workers—a group that makes up a large and growing proportion of Qatar's population. In addition, many of these workers lack knowledge of alternative healthcare facilities and rely on their employer's direction and financial support when seeking care.

This study is not without limitations. Although we used purposive recruiting, the results cannot be generalized to the female population more broadly, which is the case for most qualitative research. Nevertheless, the findings are stark and demonstrate the need for unique interventions unlike those typically used in Western countries.18 In addition, the findings cannot be generalized to male patients given that health complaints and health-seeking behaviors are gender-specific. Future research should examine the degree to which these findings differ for male patients in Qatar, the vast majority of whom are foreign laborers. Such a study could further help inform policies aimed at improving the quality of patient care, both in Qatar and in other countries with large populations of expatriate workers.

Conclusion

This was the first study to examine motivations for ED attendance in Qatar and the findings indicate different patterns than those found in Western nations.1–3,20 The unique economic and cultural environment in Qatar, and likely other Gulf states, creates different circumstances leading to ED use, particularly for expatriate workers. Expatriate workers make up a disproportionate part of the population in Qatar (85%) and represent the greatest number of patients in the ED (81%). The vast majority present with low-acuity conditions that are potentially treatable in community healthcare facilities. Interventions aimed at improving the overall quality of patient care and decreasing demand on ED resources include policy changes that require employers to either provide workers with a health card or compel employees to acquire one for themselves.

Appendix A. Semi-structured interview schedule

References

- 1.Raven MC, Lowe RA, Maselli J, Hsia RY. Comparison of presenting complaint vs discharge diagnosis for identifying “nonemergency” emergency department visits. JAMA. 2013;309:1145–1153. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1948. 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chmiel C, Huber CA, Rosemann T, Zoller M, Eichler K, Sidler P, Senn O. Walk-ins seeking treatment at an emergency department or general practitioner out-of-hours service: A cross-sectional comparison. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:94. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris ZS, Boyle A, Beniuk K, Robinson S. Emergency department crowding: Towards an agenda for evidence-based intervention. Emerg Med J. 2012;29:460–466. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.107078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson JN, Menegazzi JJ, Callaway CW. Magnitude of national ED visits and resource utilization by the uninsured. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:722–726. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagree Y, Camarda V, Fatovich D, Cameron P, Dey I, Gosbell A, McCarthy S, Mountain D. Quantifying the proportion of general practice and low-acuity patients in the emergency department. Med J Aust. 2013;198:612–615. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Statistics Authority. Qatar Population Status 2012: Three Years After Launching the Population Policy, State of Qatar.

- 7.Morgans A, Burgess S. Judging a patient's decision to seek emergency healthcare: Clues for managing increasing patient demand. Aust Health Rev. 2012;36:110–114. doi: 10.1071/AH10921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Read JG, Gorman B. Gender and health inequality. Ann Rev Soc. 2010;36:371–386. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Statistics 2012, Hamad General Hospital Emergency Department.

- 10. Hospital Episode Statistics: Accident and Emergency Attendances in England 2011-2012. Summary Report, Health and Social Care Information Centre http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB09624.

- 11.Xu M, Wong TC, Wong SY, Chin KS, Tsui KL, Hsia RY. Delays in service for non-emergent patients due to arrival of emergent patients in the emergency department: A case study in Hong Kong. J Emerg Med. 2013;45:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.11.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schull MJ, Kiss A, Szalai JP. The effect of low-complexity patients on emergency department waiting times. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higginson I. Emergency department crowding. Emerg Med J. 2012;29:437–443. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2011-200532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alyasin A, Douglas C. Reasons for non-urgent presentations to the emergency department in Saudi Arabia. Int Emerg Nurs. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2014.03.001. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgans A, Burgess S. Judging a patient's decision to seek emergency healthcare: Clues for managing increasing patient demand. Aust Health Rev. 2012;36:110–114. doi: 10.1071/AH10921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Supreme Council of Health. 2013. Website accessed on June 20, 2014. http://www.hamad.qa/en/hcp/healthcare_in_qatar/supreme_council_of_health/supreme_council_of_health.aspx.

- 17.Tuma MA, Acerra JR, El-Menyar A, Al-Thani H, Al-Hassani A, Recicar JF, Al Yazeedi W, Maull KI. Epidemiology of workplace-related fall from height and cost of trauma care in Qatar. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2013;3:3–7. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.109408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qatar National Health Accounts—1st Report 2009-2010. 2011. A Baseline Analysis of Healthcare Expenditure and Utilization, Supreme Council of Health.

- 19.Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: Causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ragin DF, Hwang U, Cydulka RK, Holson D, Haley LL, Richards CF, Becker BM, Richardson LD. 2005. (Reasons for Using the Emergency Department: Results of the EMPATH Study). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masso M, Bezzina A, Siminski P, Middleton R, Eager K. Why patients attend emergency departments for conditions potentially appropriate for primary care: Reasons given by patients and clinicians differ. Emerg Med Aust. 2007;19:333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uscher-Pines L, Pines J, Kellermann A, Gillen E, Mehrotra A. Emergency department visits for nonurgent conditions: Systematic literature review. Am J Mngd Care. 2013;19:47–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pines J, Hilton J, Weber E, Weber E, Alkemade AJ, Al Shabanah H, Anderson PD, Bernhard M, Bertini A, Gries A, Ferrandiz S, Kumar VA, Harjola VP, Hogan B, Madsen B, Mason S, Ohlén G, Rainer T, Rathlev N, Revue E, Richardson D, Sattarian M, Schull MJ. International perspectives on emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:1358–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]